ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

江川辰三 Egawa Shinzan (1928-2021)

Nom de dharma: 徹玄辰三 Tetsugen Shinzan

![]()

https://www.bukkyo-kikaku.com/archive/no121_4.htm

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%B1%9F%E5%B7%9D%E8%BE%B0%E4%B8%89

https://web.archive.org/web/20210924234939/https://www.sojiji.jp/honzan/kansyu.html

![]()

Tetsugen Shinzan 徹玄辰三 (Egawa 江川, 1928-2021)

25ème Abbé en chef (Dokujū) de Sōji-ji 总持寺独住 (2011-2021)

https://zensotobourgogne.fr/filiation/#egawa-shinzan-zenji

Egawa Shinzan naquit en 1928. Son père était abbé du temple de Seikôji. Il reçut l’ordination de moine en 1945 et la transmission du Dharma en 1949. Après des études littéraires et des études bouddhiques à l’université de Komazawa, il fit sa formation de moine à Sôji-ji, l’un des deux temples principaux de l’école Sôtô, à l’époque où Kôdô Sawaki y occupait le poste de godo (assistant de l’abbé pour l’enseignement des moines). En 1971, il devint abbé du temple de Hossenji, à Seto (près de Nagoya), où il ouvrit un dojo de pratique pour les laïcs. Par la suite, il fut nommé successivement kannin (moine cellérier) de Sôji-ji en 1996, kannin de Sôji-ji Sôin en 1999 et zenji (abbé) de Sôji-ji en 2011, fonction qu’il conserva jusqu’à sa mort en 2021.

D’un naturel chaleureux et enjoué, et d’une gentillesse communicative, il était très apprécié et respecté dans le zen Sôtô japonais. Bien qu’il eût le titre de shike (enseignant habilité à diriger un temple de formation monastique – sôdô), il avait coutume de privilégier la pratique plutôt que l’étude des textes et la réflexion philosophique. Il joua un rôle important dans le développement des échanges entre moines zen européens et japonais et dans la reconnaissance de la mission de maître Deshimaru. Bien qu’il fût très attaché à la pratique traditionnelle dans les temples japonais, dont il ouvrit les portes sans réserve aux Occidentaux qui le souhaitaient, il avait également conscience de la nécessité pour le zen européen de s’adapter aux conditions de la vie moderne.

Les disciples occidentaux d'Egawa Shinzan zenji

Pierre Crépon (1953-), nom de dharma: 道環 Dōkan (« Anneau du chemin » c'est « Pratique sans fin »*)

Abbé de Kokaiji, enseignant de l’école Sôtô (seikyoshi).

https://templezen-kokaiji.org/team/reverend-dokan-crepon/

https://www.facebook.com/templezensotokokaiji/

Né en 1953, Pierre Crépon commence la pratique à l’âge de 20 ans et reçoit l’ordination de moine de Maître 泰仙弟子丸 Taisen Deshimaru en 1975. Il devient l’un de ses proches disciples et suit quotidiennement son enseignement au dojo de Paris et lors de différentes sesshin dans toute l’Europe. Il est alors rédacteur en chef de la revue "Zen" de l’AZI (Association Zen Internationale) (de 1977 à 1987) et aide à l’organisation des camps d’été. Parallèlement, il poursuit des études universitaires d’histoire et d’archéologie.

Après la mort de Maître Deshimaru, en 1982, il continue de pratiquer au sein de l’Association Zen Internationale, dont il a été l’un des responsables, et dirige des sesshins au temple de La Gendronnière. Il quitte l’AZI en 2015. Il a été président de l’Union bouddhiste de France de 2003 à 2007.

Il s’installe avec son épouse Brigitte 清城 Seijô à Vannes en Bretagne en 1994 où ils créent un dojo zen qui devient le temple Kokaiji (古海寺 temple de l’Ancien Océan) en 2003. Dans le même temps il entreprend de renouer avec la tradition du zen japonais. Grâce au Révérend 堀部明宏 Myôkô Horibe qui avait été assistant de maître Deshimaru à Paris, il rencontre Shinzan Egawa Rôshi, alors administrateur (Kannin) du grand temple Sôjiji, dont il devient disciple et dont il reçoit la transmission du Dharma en 1998. Par la suite il continue de faire de nombreux voyages au Japon, séjourne dans différents temples et participe au rapprochement entre le zen européen et japonais.

Par ailleurs, en 1992, il fonde avec Brigitte les Éditions Sully, qui publient notamment des ouvrages sur le bouddhisme (comme la traduction par 折茂洋子 Yokô Orimo du Shôbôgenzô de maître Dôgen) et sur la culture japonaise. Il est également l’auteur de nombreux articles et de plusieurs ouvrages (Dictionnaire de la spiritualité orientale, Les Fleurs de Bouddha, Pratiquer le zen, Contes et paraboles du Bouddha).

Il a donné la transmission du Dharma à Marie-Odile Reimyô Blaise, responsable de la couture du Kesa au temple, et à Alix Myôshô Helme-Guizon, responsable du dojo zen d’Angers.

Extrait du livre Pratiquer le zen (1996)

Sa bibliographie aux éditions Sully:

Contes et paraboles du Bouddha

Dictionnaire pratique de l'acupuncture et du shiatsu

L'art du zazen

S'oublier soi-même en suivant la voie du zen

Katia Robel (1948-), nom de dharma: 妙空香蓮 Myōkū Kōren (« Merveilleux vide, Parfum de lotus »)

Ordonnée nonne en 1971 par maître Taisen Deshimaru, Katia Kôren Robel reçoit en 2003 la transmission du Dharma du grand maître Shinzan Egawa. Présidente de l’Association Zen Soto, elle enseigne principalement au temple de Myô-Unji en Bourgogne et à Paris.

https://zensotobourgogne.fr/enseignants/

https://associationzensotoparis.fr/qui-sommes-nous/katia-koren-robel/

Dès 1970, Katia Kôren Robel pratique quotidiennement zazen à Paris sous la direction de maître Taisen Deshimaru. Ce dernier lui confère l’ordination de nonne en 1971. Pendant les années qui suivent, elle travaille notamment à la publication de ses textes. Après le décès de maître Deshimaru en 1982, elle commence à enseigner le zen au Dojo Zen de Paris, puis au temple zen de la Gendronnière et dans des retraites (sesshin) en France et en Europe. En 2003, elle reçoit la transmission du Dharma (shihō) de maître Egawa Shinzan et devient enseignante certifiée (kyoshi) de l’école Sôtô japonaise.

Présidente du Dojo zen de Paris de 1996 à 2006, elle a ensuite créé l’Association zen Sôtô (AZS) et enseigné au Dojo zen du Châtelet, à Paris, jusqu’en 2020. Elle est aujourd’hui présidente de l’AZS, membre du conseil spirituel de l’Association zen Internationale (AZI) et membre du conseil d’administration de l’Union Bouddhiste de France (UBF). Elle enseigne principalement au temple de Myô-Unji et à Paris.

https://sotozen.actibookone.com/content/detail?param=eyJjb250ZW50TnVtIjoxNzYxMDJ9&detailFlg=0&pNo=8

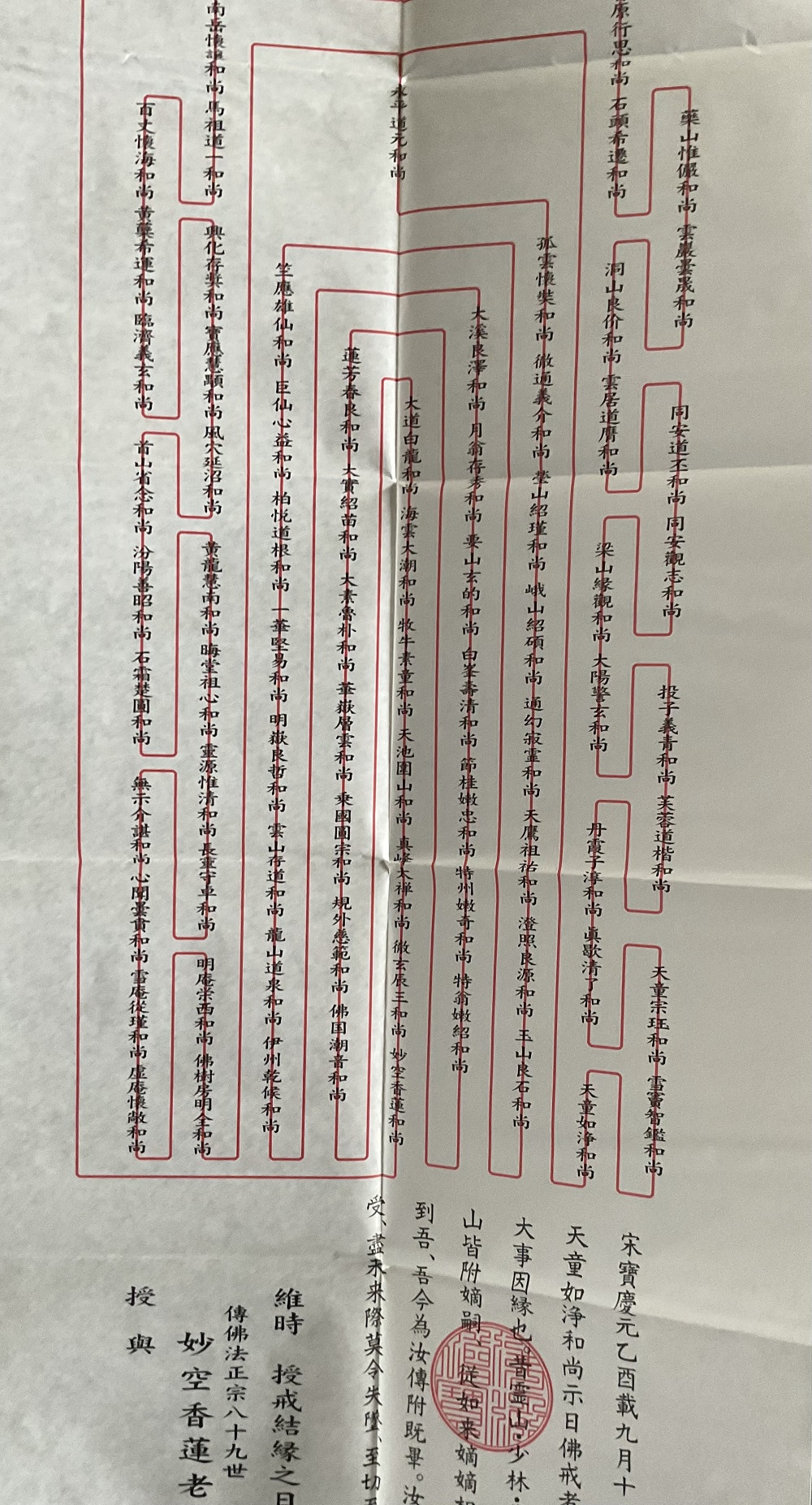

佛祖正傳菩薩大戒血脈

Busso shōden bosatsu daikai kechimyaku

The Bloodline of the Buddha’s and Ancestors’ Transmission of the Great Bodhisattva Precepts[…]

永平道元 Eihei Dōgen (1200-1253)

孤雲懐奘 Koun Ejō (1198-1280)

徹通義介 Tettsū Gikai (1219-1309)

螢山紹瑾 Keizan Jōkin (1268-1325)

峨山韶碩 Gasan Jōseki (1275-1366)

通幻寂靈(=灵) Tsūgen Jakurei (1322-1391)

天鷹祖祐 Tenyō Soyū (1336-1413)

澄照良源 Chōshō Ryōgen (1354-1427)

玉山良石 Gyokusan Ryōseki

竺翁雄山 Chikuō Yūsen

巨川心益 Kyosen Shinyaku

柏悅道根 Hakuetsu Dōkon

一華堅易 Ichike Keneki

明岳良哲 Meigaku Ryōtetsu

雲山存道 Unsan Sondō

龍山道泉 Ryū Dōsen

位州乾候 Ishū Genkō

大渓良澤 Takei Ryōtaku

月翁存秀 Gatsuō Sonshū

要山玄的 Yōsan Genteki

白峰寿清 Hakuhō Jusei

節桂嫩忠 Setsukei Donchū

特州嫩奇 Dokushū Donki

霊峰嫩紹 Reihō Donshō

連峯春良 Renhō Shunryō

大實紹苗 Tajitsu Shōmyō

太素魯朴 Taso Roboku

華嶽層雲 Kagaku Sōun

乗国圓宗 Jōkoku Enshū

規外慈範 Kigai Jihan

佛国潮音 Butsukoku Chōin

大道白龍 Taidō Hakuryū

海雲大潮 Kaiun Daichō

牧牛素童 Bokugyū Sodō (石川 Ishikawa, 1841-1920) (4. Chief Abbot (Dokujū) of Sōji-ji 总持寺独住)

天池圓山 Tenchi Ensan

東峰太禅 Tōhō Taizen

徹玄辰三 Tetsugen Shinzan (江川 Egawa, 1928-2021) (25. Chief Abbot (Dokujū) of Sōji-ji 总持寺独住)

妙空香蓮 Myōkū Kōren (Katia Robel 1948-)

Situation of the diffusion of Zen in Europe

by Rev. Koren Robel

Dharma Eye, Soto Zen Journal. March 2022, No. 49. pp. 8-10.In just over fifty years, from north to south,

from Norway to Spain, and from west to east,

from Portugal to Poland, Zen has spread throughout

Europe. It was in 1967 that the practice of

Zen was established in Europe thanks to the

arrival of the Zen monk of the Rev. Taisen Deshimaru

in Paris. He did not come to take care of

Japanese communities as was the case with the

first Zen monks in America. He came on his own

initiative in a missionary spirit to spread Zen

practice and philosophy in the West.Rev. Taisen Deshimaru was an atypical

monk. He was endowed with great charisma,

unshakable energy and faith, and a deep knowledge

of both human beings and the Zen tradition

and Far Eastern culture. His mission, which

lasted fifteen years, was a great success. Settled

in Paris, his teaching spread throughout Western

Europe. He firmly established the practice of

zazen, translated the great Zen texts, and introduced

rituals and chants. He was responsible for

the creation of more than a hundred dojos and

practice groups throughout Europe, as well as

the Gendronnière temple in 1980 in the Val-de-

Loire, France. He was the first kaikyosokan in

Europe in 1976, and from then on, many Japanese

delegations came to visit him and several

young Japanese monks came to help him. He

gathered many disciples around him, ordaining

more than 500 monks and nuns, and it is said

that more than 20,000 people have at one time

or another practiced with him. In 1970 he

founded the European Zen Association, which

became the International Zen Association (IZA)

in 1979. Forty years after his death in 1982, his

memory and energy remain very much alive and

underpin the situation of Zen in Europe.Rev. Taisen Deshimaru passed away in 1982,

having trained disciples but not given Dharma

transmission. In the years that followed, and

although several disciples received transmission

from other Japanese masters fairly quickly -

notably Rev. Shuyu Narita and Rev. Renpo Niwa

Zenji - the situation was somewhat confused and

different choices were made concerning the relationship

with the Japanese tradition, the transmission

and the relationship with the Soto

School. Some of his former disciples remained

and still remain fiercely opposed to any affiliation

with the institution (Shumucho). For about

twenty years, there was no kaikyosokan or European

office of the Soto School in Europe.Finally, things became clearer from the end

of the 1990s. Most of Master Deshimaru’s

disciples, who had become teachers, returned to

Japan and received the transmission from various

Japanese masters. As other Europeans went

to practice in Japanese temples (Eiheiji, Sojiji,

Sojiji Soin, Eiheiji Betsuin, Nisodo, Antaiji, etc.)

and also received transmissions, there are a

large number of lineages in Europe from different

Japanese masters. There are also some

lineages from the United States. Since 2002, a

new European office of the Japanese school has

been set up, first in Milan and then in Paris,

which has created a link between these different

lineages. Training seminars, organised by the

Sokanbu at the Gendronnière temple, regularly

bring together oshos, kyoshis and kokusai

fukyoshis from all over Europe, who can on

these occasions meet, get to know each other

and have exchanges. The hossenshiki and shinzan

ceremonies, organised in the temples, are

also the occasion for regular meetings, as are the

two ojukai ceremonies, led by Rev. Minamizawa

Zenji, which took place for the first time outside

Japan in 2016 at the Gendronnière and in 2019 at

Kanshoji, and the commemoration ceremonies.Today, the second-generation teachers generally

follow the classical Soto school curriculum

and go to practice ango in the sodo in Japan,

mainly in Toshoji (Okayama prefecture). There

were two shuritsu senmon sodo at the Gendronnière

in 2007 and 2008, organised by the Sotoshu

Shumucho for the first-time outside Japan, and

with the presence of teachers such as Shohaku

Okumura. But since then, the ango held in various

temples are not yet officially recognized by

the school for the training of monks. There are

currently several Soto School temples in Europe,

some of which are monastery-type temples in

the countryside and others in the city.There are also a large number of groups who

voluntarily keep away from the Soto School and

its rules, because they want to preserve their

independence at all costs and create a "European

Zen" with its own forms, "independent"

lineages, while practicing zazen and simplified

rituals. Since some of the teachers are affiliated

with the school and others are not, these risks

creating confusion and difficulties for the future,

even though the form of the practice is mostly

the same.In fact, the living fabric of Zen in Europe is

made up of a great many small practice groups

scattered around the cities, as well as isolated

individuals, and then a few dozen dojos and

larger centers and a few temples, all run by

monks and nuns and teachers (65 kyoshis, 52

kokusai fukyoshis). All these people and places

of practice are generally organized in a network,

linked to a temple or a teacher, within an association

or not. The International Zen Association,

founded by Master Deshimaru, is probably

the most important - it has more than 1,100

members and 9 temples, 9 zen centers, 73 dojos

and 129 groups - but there are others, in Germany,

Italy, Belgium, etc.The great diversity of lineages, associations,

and of course countries with different languages

and cultures, does not prevent a certain unity of

European Zen, such as the central place of

zazen, the black koromo, the sewing of the kesa,

the teaching of Zen texts and the practice of

traditional rituals, more or less advanced, most

often using the recitation of sutras in Sino-

Japanese. In general, European Zen groups are

not overly concerned with social affairs and do

not get involved in political affairs. They also

differ from many other mindfulness-type groups,

and preferably follow a traditional form appropriate

to the circumstances.The last two years have obviously been a bit

complicated with the Covid pandemic. Some

groups have adopted video-conferencing teaching,

others have not. At the moment, we are

hopeful that this pandemic will end and that

second-generation teachers will be able to train

in Japan again, that it will be possible to do

zuise there again and that the number of kyoshis

will increase, thus showing the vitality of Zen.