ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

西堂智藏 Xitang Zhizang (735–814)

(Rōmaji:) Seidō Chizō

(Magyar átírás:) Hszi-tang Cse-cang

Tartalom |

Contents |

| Hszi-tang Cse-cang, 735-814 Fordította: Terebess Gábor |

XITANG ZHIZANG Hsi-t'ang Chih-tsang Xitang Zhizang Chan Master Qianzhou Xitang Zhicang Case 78: 馬祖翫月 Mazu's Moon Viewing Case 248: Shigong's Emptiness |

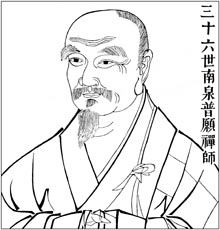

Xitang Zhizang: 西堂智藏 [Seidō Chizō]. 735–814. Dharma heir of Mazu Daoyi, Nanyue Line. Zhizang, Huahai, and Nanquan Puyuan were the three most outstanding students of Mazu, who praised the former two by saying, „Zang head is white, Hai's head is black.” His posthumous name is Zen Master Dajiao, 大覺禪師. His disciples: 虔州處微 Qianzhou Chuwei (d.u.); 증각홍척 (證覺洪陟) Jeunggak Hongcheok (d. 828?) Korea. 實相山 Silsang san school; 체공혜철 (體空惠哲) Chegong Hyecheol (785–861) Korea. 桐裡山 Tongni san school; 명적도의 (明寂道義) Myeongjeok Doui (d. 825) Korea. 迦智山 Kaji san school.

XITANG ZHIZANG

by Andy Ferguson

In: Zen's Chinese Heritage: The Masters and Their Teachings, Wisdom Publications, pp. 92-93.

XITANG ZHIZANG (735–814) was a student of Mazu Daoyi. He came from Qianhua City in ancient Qian Province.60 When young, he had an unusually noble appearance. People said that he would likely be an “assistant to the Dharma King” (a servant of Buddha). After receiving ordination at the age of twenty-five, he went traveling, and finally came to study under Mazu Daoyi. A fellow student of Baizhang, they together received Dharma transmission from Master Ma.

Among Zhizang’s numerous disciples were the Korean monks Jilin Daoyi and Hongshe. These two adepts transmitted Zen to their native country. There, they helped to establish the “Nine Mountains,” nine prominent schools of Korean Zen.

One day Mazu dispatched Zhizang to Changan to deliver a letter to the National Teacher [Nanyang Huizhong].

The National Teacher asked him, “What Dharma does your teacher convey to people?”

Zhizang walked from the east side to the west side and stood there.

The National Teacher said, “Is that all?”

Zhizang then walked from the west side to the east side.

The National Teacher said, “This is Mazu’s way. What do you do?”

Zhizang said, “I showed it to you already.”

One day Mazu asked Zhizang, “Why don’t you read sutras?”

Zhizang said, “Aren’t they all the same?”

Mazu said, “Although that’s true, still you should do so for the sake of people [you will teach] later on.”

Zhizang said, “I think Zhizang must cure his own illness. Then he can talk to others.”

Mazu said, “Late in your life, you’ll be known throughout the world.”

Zhizang bowed.

The magistrate Lu Sigong invited Mazu to come to his prefecture for a length of time and convey the teaching. At that time, Zhizang, receiving from Mazu his hundred-sectioned robe, returned to his home province and began receiving students.

A monk asked Zen master Zhizang, “There are questions and there are answers. There is distinguishing guest and host. What about when there are no questions or answers?”

Zhizang said, “I fear it’s rotted away!”

After Zhizang became abbot of the Western Hall [in Chinese, Xitang], a layperson asked him, “Is there a heaven and hell?”

Zhizang said, “There is.”

The layman then asked, “Is there really a Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha—the three jewels?”

Zhizang said, “There are.”

The layman then asked several other questions, and to each Zhizang answered, “There are.”

The layman said, “Is the master sure there’s no mistake about this?”

Zhizang said, “When you visited other teachers, what did they say?”

The layman said, “I once visited Master Jingshan.”

Zhizang said, “What did Jingshan say to you?”

The layman said, “He said that there wasn’t a single thing.”

Zhizang said, “Do you have a wife and children?”

The layman said, “Yes.”

Zhizang said, “Does Master Jingshan have a wife and children?”

The layman said, “No.”

Zhizang said, “Then it’s okay for Jingshan to say there isn’t a single thing.”

The layman bowed, thanked Zhizang, and then went away.

Zen master Zhizang died on the eighth day of the fourth month in [the year 814]. The emperor Xuan Zong gave him the posthumous name “Zen Master Great Expounder of the Teaching.” The emperor Mu Zong renamed him “Zen Master Great Awakening.”

Hsi-t'ang Chih-tsang

In: Sun-Face Buddha

The Teachings of Ma-Tsu and the Hung-chou School of Ch'an

Translated by Cheng Chien Bhikshu (Mario Poceski)

pp. 69, 72-73, 97-99, 117.

Hsi-t 'ang Chih-tsang or Hsi-fang Chih-bang (734-814) was a native of Ch'ien-hua.1 At the age of

eight he [left home and followed his master; at the age of twenty-five he received the precepts [of a

bhikku]. Later he went to study with Ma-tsu, and together with Pai-chang they were his two close

disciples who received his approval. He stayed with Ma-tsu until the latter's death, after which the

monks invited him to become abbot and start to teach.

One day Ta-chi sent the Master to the capital of Chang-an to deliver a letter to The National Teacher Hui-chung.2 The National Teacher asked him, "What is your master teaching?"

The Master walked from east to west, and then stood there.

The National Teacher asked, "Only that? Anything else?"

The Master walked back to the east, and then stood there.

The National Teacher said, "This is what you have learned from Master Ma. How about anything of your own?"

The Master replied, "I have already shown it to the Venerable".

One day Ma-tsu asked the Master, "Why don't you study sutras?"

The Master replied, "How could the sutras be different?"

Ma-tsu said, "Though it is so, still, later you will need to use them for the sake of other people."

The Master replied, "Chih-tsang should [first] try to cure his own illnesses; how can he dare to concern himself with other people."

Ma-tsu said, "Later on, you will become well known in the world."

Secretary of State Li Ao ch'ang once asked a monk, "What was the teaching of the Great Master Ma?" The monk replied, "The Great Master sometimes would say that mind is Buddha; sometimes he would say that it is neither mind nor Buddha."

Li said, "All pass here." Li then asked the Master, "What was the teaching of the Great Master Ma?

The Master called, "Li Ao!" Li responded. The Master said, "The drum and horn moved."

Ch'an Master Chih-kung said to the Master, "The sun is rising too early."

"Just on time." responded the Master.

After the Master came to stay at Hsi-t'ang, there was a layman who asked him, "Are there heavens and hells?"

The Master replied, "Yes, there are."

The layman asked, "Are there the [three] treasures of the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha?'

The Master replied. "Yes, there are."

Then the layman asked many questions, on all of which the Master replied in positive.

The layman asked, "Isn't there any mistake in the Venerable speaking this way?"

The Master asked him "Have you seen any virtuous monks already?"

The layman said, "I went to see Venerable Ching-shan."3

The Master asked, "What did Ching-shan have to tell you?"

The layman said, "He said that there are none of those at all."

The Master asked him, "Do you have a wife?"

The layman said, "Yes, do."

The Master asked, "Does Venerable Ching-shan have a wife?"

The Layman replied, "No, he doesn't."

The Master said, "Then it is alrtght for him to say that there is none"

The layman bowed, thanked the Master, and went away.

NOTES

1 In present-day Kiangsi province.

2 For National Teacher Hui-chung, see "Formation of the Ch'an School" in the Introduction.

3 For Ching-shan see note 63 on the Record ofMa-tsu.

Once Hsi-t'ang, Pai-chang, and Nan-ch'üan accompanied the Patriarch Ma-tsu to watch the moon.

The Patriarch asked, "What shall we do now?"

Hsi-Tang said, "We should make offerings."

Paichang said, "It is best to practice."

Nanch'üan shook his sleeves and went away.

The Patriarch said, "The sutras enter the treasury, meditation returns to the sea. It is P'u-yüan alone that goes beyond all things."41

41 The sentence "The sutras enter the treasury" refers to Hsi-t'ang whose Dharma-name is Chih-

tsang, tsang meaning treasury. "Meditation returns to the sea" refers to Pai-chang whose Dharma-

name is Huai-hai, the meaning of the character hai being sea. P'u-yüan is the Dharma-name of Nan-ch'üan.

A monk asked the Patriarch Mazu, "Without using the four phrases and the hundred negations,47 may the Venerable directly point out to me the meaning of [Bodhidharma's] coming from the West."

The Patriarch said, "Today I do not feel like doing that. You can go and ask Chih-tsang."48

The monk [went to] Chih-tsang and asked the same question.

Chih-tsang said, "Why don't you ask the Venerable Master?"

The monk replied, "He sent me here to ask your Reverence."

Chih-bang rubbed his head with his hand, and said, "I am having a headache today. You can go and ask my elder Dharma-brother Hai."49

The monk went to Huai-hai and asked the same question.

"I don't know anything about it." was Hui-hai's reply.

Later the monk told the Patriarch what had happened.

"Chih-tsang's head is white; Hui-hai's is black." commented the Patriarch.

47 The four phrases are existence, emptiness, both existence and emptness, and neither existence

nor emptiness. They are used to elucidate all the phenomena in the universe are unborn. As to the

phrase "hundred negations," the number hundred is used to symbolize a very big number, while

negations such as not existent, not non-existent, not permanent or impermanent, etc., are used to

point out that the ultimate reality is beyond verbal descriptions. In Sun-lun hsuan-i, a treatise by the

T'ang Dynasty San-lun school's monk Chia-hsiang, there is the sentence: "If one were to discuss

Nirvana, its essence is beyond the four phrases and its reality transcends the hundred negations."

The question of the monk can be interpreted to mean: "Without using any form of verbal

expression, please point out to me directly the ultimate reality."48 Hsi-t'ang Chih-tsang.

49 Pai-chang Huai-hai.

Shih-kung Hui-tsang Master asked Hsi-t'ang, "Do you know how to grasp empty space?"

Hsi-t'ang said, "Yes, I know."

The Master asked, "How can you grasp it?"

Hsi-t'ang made a gesture as if trying to grasp the empty space with his hand.

The Master said, "How can you grasp an empty space in that way?"

Hsi-tang asked, "How is my elder Dharma-brother is going to grasp it?"

The master grabbed Hsi-t'ang's nostril and pulled it.

Hsi-t'ang cried with pain and said, "You are pulling my nostril to death. Stop it immediately."

The master said "This is the way to grasp empty space".

Xitang Zhizang

In: Ordinary Mind as the Way

The Hongzhou School and the Growth of Chan Buddhism

by Mario Poceski

Following Mazu's death in 788, Xitang became the leader of the monastic community at Kaiyuan monastery.10 He

taught there for at least the next few years, and Mazu's followers looked to him for guidance more than any other

senior disciple.11 Despite Xitang's prominent role, Chan sources provide little information about him. His biographies

in the Chan chronicles, including Chuandeng lu, are brief, and he was not accorded a record of sayings. The lack of

biographical information about Xitang during the tenth century is evident in Zutang ji. There, toward the end of

Xitang's brief hagiographic entry, which contains virtually no biographical information, the compilers note: “Besides

these [three short stories], we have not seen any other records about his activities, and the dates of his death and birth

are not known.”12 Moreover, although Zanning allocated separate biographies to more than thirty of Mazu's disciples

in Song gaoseng zhuan, he did not provide a full biographical entry for Xitang, possibly because of a lack of sufficient

information. The text of Xitang's stele inscription was not widely circulated and was not included in the standard

collections of documents from the Tang period. With the exception of a few short stories of questionable provenance,

there are also no records of Xitang's teachings.Xitang's neglect at the hand of later writers and historians reflects a subsequent demotion of his stature. After the Tang

period, other monks, in particular Baizhang and Nanquan, supplanted him as leading representatives of the Hongzhou

school's second generation. Even so, because his historical position as Mazu's leading disciple was established, he could

not be ignored, and Chan chronicles usually mention him as one of Mazu's two main disciples, along with Baizhang.13

Xitang's emergence as one of Mazu's principal disciples goes back to the late 760s, when Mazu left him in charge of the

monastic community at Gonggong mountain at the time of Mazu's move to Hongzhou. He also appears second, after

Dazhu, in the list of senior disciples in Mazu's stele inscription.14 Another indication of Xitang's prominence comes

from an inscription for a monastery in Mazu's native Sichuan that was composed by the famous poet Li Shangyin

(812–858).15 The inscription commemorates Mazu, Xitang, Wuxiang, and Wuzhu. Xitang was presumably included in

that illustrious company as a representative of Mazu's disciples, even though he is the only one of the four monks with

no connection to Sichuan. Zongmi's Pei xiu sheyi wen also mentions Xitang—together with Huaihui, Baizhang, Weikuan,

and Daowu—as one of the five main disciples of Mazu.16 Predictably, Xitang's stele inscription describes him as Mazu's most

influential and capable disciple. It states that Xitang and Weikuan were the two main disciples whose teachings flourished

in the South and the North, respectively.17 That statement suggests an analogy with the famous representation of Shenxiu

and Huineng as the Chan school's leaders in the North and the South, respectively. Song gaoseng zhuan also states that

Xitang received Mazu's robe. Since the transmission of the robe served as a metaphor for the transmission of Chan enlightenment,

Mazu's putative bestowal of his robe indicates the selection of Xitang as his spiritual successor.18Xitang was born in 738 in Qianhua prefecture (in present-day Jiangxi).19 His family name was Liao. He entered

monastic life when he was only eight years old. In 750, at the age of twelve, he joined Mazu, who at the time was

residing at Xili mountain in Fuzhou.20 The young novice followed Mazu in the move to Gonggong mountain, located

in Xitang's native prefecture.21 In 761, at the age of twenty-three, Xitang received full monastic ordination.22 As has

been noted, when two decades later Mazu received an invitation to take up residence in Hongzhou, he left Xitang to

lead the community at Gonggong mountain. During the later part of his life, Xitang emerged as a prominent and well-

connected Chan teacher. His lay disciples included powerful local officials such as Li Jian and Qi Ying (748–795).23

Li became Mazu's disciple and supporter after he assumed the position of governor of Jiangxi in 785.24 Li and Xitang

were together involved in the organization of Mazu's funeral. Subsequently, Li remained a supporter of the monastic

community and continued his study of Buddhism with Xitang. Qi Ying, a jinshi examination graduate, Regional Spread of

the Hongzhou School followed Li Jian as a civil governor of Jiangxi after 791.25 Another official connected to Xitang was

Li Bo (773–831), the author of his first stele inscription.26Xitang's biography in Chuandeng lu also records this conversation between him and the famous Confucian apologist

Li Ao (772–841):Secretary of State Li Ao once asked a monk, “What was the teaching of Great Master Ma?”

The monk replied, “The Great Master sometimes would say that mind is Buddha; sometimes he would say that it is

neither mind nor Buddha.”Li said, “All pass here.” Li then asked the master [i.e., Xitang], “What was the teaching of the great master Ma?”

The master called, “Li Ao!”

Li responded.

The Master said, “The drum and the horn moved.”27

There is not much information about the last two decades of Xitang's life. Presumably he spent his late years at

Gonggong mountain. He died in 817, at the age of seventy-nine. His disciples erected him a stūpa on the grounds of

the monastery on Gonggong mountain. According to the stele inscription, at the time of his death Xitang did not

suffer from any illness. He simply asked his disciples to assemble and then quietly departed from this world. In 824,

Emperor Muzong (r. 820–824) posthumously bestowed on him the title Dajue (Great Awakening), in response to a

request made by Li Bo.28His memorial pagoda was named Da bao guang (Great Precious Light). Wei Shou (dates of birth and death unknown)

compiled a record of Xitang's teachings and life, which is no longer extant.29Xitang did not have disciples who made any notable impact on the subsequent history of Chan in China, which is one

reason behind his neglect by later historians.30 On the other hand, he was a teacher of Korean monks who exerted

significant influence on the growth of the Chan (Sŏn) tradition on the Korean peninsula. Three of the reputed founders

of the main Sŏn schools that emerged during the Silla dynasty—Toŭi (d. 825), Hongch'ŏk (fl. 826), and Hyech'ŏl (785–

861)—were disciples of Xitang. The first of the Korean monks to come to study with Xitang was Toŭi. According to his

biography, he met Xitang while the latter was residing at Kaiyuan monastery.31 This meeting probably happened after

Toŭi's arrival in China in 784. After his study with Xitang, Toŭi also visited Baizhang's monastery. The

Korean monks presumably went to study with Xitang because at the time he was Mazu's best-known disciple;

consequently, he ended up attracting the largest number of Korean disciples among his contemporaries.

Chan Master Qianzhou Xitang Zhicang

景德傳燈錄 Jingde chuandeng lu

虔州西堂智藏禪師 T.51, no.2076, 252a12 398 289 104

Daoyuan. Records of the Transmission of the Lamp: Volume 2 (Books 4-9), The Early Masters, Book 7.109

Translated by Randolph S. Whitfield

Chan master Xitang Zhicang218 of Qianzhou (Jiangxi) (735-814 CE) was a native of Qianhua (Jiangxi) whose family name was Liao. From the age of eight he followed a teacher and received the full precepts at twenty-five. A physionomist, gazing at his extraordinary appearance, said to him, ‘The master’s build is not of the normal. He will surely be the right-hand man of a King of the Dharma.’ The master then journeyed to the Buddha’s Footprint Cliff in order to train under Daji (Mazu). Together with Baizhang, he was among the ones who ‘entered the room’ and inherited the seal of transmission.

One day Mazu sent the master to Chang’an to deliver a letter to the National Teacher. The National Teacher asked him, ‘What Dharma does your master teach?’ The master then walked from the east side [of the room] to the west side and remained standing.

‘Just this, or is there something else?’ asked the National Teacher.

The master then walked back to the east side and remained standing.

‘This is Mazu’s, what about yours, Good Sir?’

‘It’s just been submitted to the venerable sir,’ replied the master.

Thereafter Master Xitang was again sent with a letter to Chan master Guoyi at Jing Mountain. Then Commander-in-Chief Luo Sigong extended an invitation to Daji (Mazu) to come and reside in his prefecture. Thereupon, his teaching immediately began to flourish. Master Xitang criss-crossed the whole area, having obtained Daji’s Robe of Transmission, to show to students everywhere.

A monk asked Mazu, ‘Apart from the Four Phrases and the One Hundred Negations, could the venerable sir please point this fellow directly to the meaning of the coming from the West?’

‘I am out of sorts today,’ responded Mazu, ‘you should go and get it from Zhicang.’

The monk then came to ask the master (Xitang Zhicang). The master said, ‘Why don’t you ask the Venerable [Mazu]?’

‘Mazu sent this fellow to ask the head monk,’ replied the monk.

The master, stroking his head, said, ‘Having a headache today, you would be better off going to ask Elder Brother Hai.’ (Baizhang Huaihai).

The monk then went to Baizhang, who responded, ‘I really don’t understand this.’

The monk brought all this up with Mazu, who said, ‘Cang’s head is white, Hai’s head is black.’222

Mazu one day asked the master, ‘Why do you not read the sutras?’ ‘Would the sutras be so different?’ asked the master.

‘Alright, but for the sake of others in the future you should have them,’ said Mazu.

‘Zhicang thinks to cure his own sickness, would he dare then teach others?’ said the master.

‘In later years you will certainly rise in the world,’ said Mazu.

After Mazu died, the master was invited by the assembly to open the hall.223 This was in the 7th year of the Zhenyuan reign period of the Tang (791 CE).

Minister Li Ao224 once asked a monk, ‘What was the teaching of Patriarch Ma[zu]?’

‘The Patriarch taught either “Heart is Buddha” or “Not Heart, Not Buddha”’, answered the monk.

‘Everyone has passed this way,’ said Li Ao.

Li Ao then asked the master, ‘What was the teaching of Patriarch Ma?’

The master called out, ‘Li Ao!’

‘Yes,’ he replied.

‘Drum and horn have moved,’ said the master.

Master Zhigong said to the master, ‘When the sun comes out the great morning is born.’

‘Right on time,’ replied the master.

When the master was residing in the western hall, a layman asked him, ‘Are there heavenly mansions and deep hells or not?’

‘There are,’ replied the master.

‘Are there three treasures – Buddha, Dharma and Sangha – or not?’ asked the layman.

‘There are,’ replied the master.

Many other such questions followed and to each of them the master replied, ‘There are.’

‘Is the venerable sir not mistaken in answering everything in this way?’ asked the layman.

‘Have you ever seen an old monk?’ asked the master.

‘This fellow has trained under Guo of Jingshan,’225 answered the layman.

‘What did the venerable Jingshan have to say to you?’ asked the master.

‘He always said things are “not”,’ answered the layman.

‘Do you have a wife or not?’ asked the master.

‘I have,’ answered the layman.

‘Did the venerable Jingshan have a wife or not?’

‘He had not,’ replied the layman.

‘When the venerable Jingshan said “not” that was correct,’ said the master.

The layman bowed in gratitude and withdrew.

On the 8th day of the 4th month of the 9th year of the Yuanhe reign period (814 CE) the master returned to quiescence, at the age of eighty, having been a monk for fifty-five years.

Emperor Xianzong (r.806-21) conferred on him the posthumous title of ‘Chan Master Great Proclaimer of the Teachings’ and his memorial tower of the Yuanhe period was called ‘Witness to the Real’.

Emperor Muzong (r.821-4) conferred the additional title of ‘Chan Master of Great Awakening’.

NOTES

218 One of the three great Dharma-heirs of Mazu, with Nanquan Puyuan and Baizhang Huaihai.

222 The story of two robbers: a black-capped one tricked a white-capped one of all the goods he had stolen, i.e. the black-capped one was more radical, even thieving from thieves. (John Wu, The Golden Age of Zen, 103)

223 To occupy Mazu’s place and carry on the teaching.

224 Li Ao (772-841) was a famous literatus, political thinker and opponent of Buddhism who advocated a return to the ‘Golden Mean’ of Confucius.

Xitang Zhizang (Hsi-tang Chih-tsang, Seidō Chizō; 735–814

In:

Entangling Vines: Zen Koans of the Shūmon Kattōshū

Translated by Thomas Yūhō Kirchner

Case 78:

馬祖翫月 Mazu's Moon ViewingOnce Baizhang Huaihai, Xitang Zhizang, and Nanquan Puyuan were attending Mazu as they viewed the autumn moon. Mazu asked them what they thought of the occasion.

Xitang said, “It’s ideal for a ceremony.”

Baizhang said, “It’s ideal for training.”

Nanquan shook his sleeves and walked away.1

Mazu said, “Zhizang has gained the teachings, Huaihai has gained the practice, but Puyuan alone has gone beyond all things.”2

NOTES

1 To shake one’s sleeves expresses scorn or may alternatively indicate leave-taking.

2 Mazu’s rejoinder is partly a play on words involving the names of Xitang Zhizang and Baizhang Huaihai . The first two lines of his comment can be read, “Teachings enter the library (for ); practice returns to the sea (for ).”

Shigong's Emptiness

In: The True Dharma Eye: Zen Master Dogen's Three Hundred Koans

with commentary and verse by John Daido Loori, translated by Kazuaki Tanahashi and John Daido Loori

蔡志忠 Cai Zhizhong's cartoon

Case 248:

Shigong’s EmptinessMAIN CASE

Master Shigong Huizang asked Zhigong, a former abbot, “Do you know how to grasp emptiness?”1

Zhigong said, “Yes, I know how to grasp emptiness.”2

Shigong said, “How do you grasp it?”3

Zhigong grasped at the air with his hand.4

Shigong said, “You don’t know how to grasp emptiness.”5

Zhigong responded, “How do you grasp it, elder brother?”6

Shigong poked his finger in Zhigong’s nostril and yanked his nose.7

Zhigong grunted in pain and said, “It hurts! You are pulling off my nose.”8

Shigong said, “This is how to grasp it.”9COMMENTARY

Zhigong’s potential is stuck in a fixed position, so Master Shigong is compelled to shake

him loose. If you want to free what is stuck and loosen what is bound, you must simply

cut away all traces of thought, let go of all words and ideas, and experience it directly.

This whole great earth is contained in a single speck of dust. When a single flower

blooms, the ten thousand things come into being.

Although in yanking Zhigong’s nose, Shigong was able to hide in his nostrils, we should

understand that the truth of this kōan is not to be found in the nose or the finger. What is

the truth of this kōan? Indeed, what does it mean that Shigong was able to hide in

Zhigong’s nostrils?CAPPING VERSE

From within the single body,

myriad forms arise.

In one, there are many kinds;

in many kinds, there is no duality.NOTES

1. Shaking the tree, he wants to see what falls out.

2. The tree leaned and fell over.

3. It wouldn’t do to let him go on like this.

4. Oops! Them bones, them bones, them dry bones.

5. He can only call it as he sees it.

6. After all, at this point he must ask.

7. Very intimate, very intimate indeed.

8. It fills the universe. There is no place it does not reach.

9. His eyebrows have fallen off. Too bad.

cf. 75 On The Unbounded (Kokū)

http://shastaabbey.org/pdf/shobo/075koku.pdf

In: The Shōbōgenzō

PDF: The Treasure House of the Eye of the True Teaching

Rev. Hubert Nearman, O.B.C., Translator

Shasta Abbey Press, 2007

Hszi-tang Cse-cang, 735-814

Fordította: Terebess Gábor

Folyik a híd, Officina Nova, Budapest, 1990, 24, 29. oldal

Egyszer a három tanítvány, Nan-csüan, Hszi-tang és Paj-csang elkísérte Ma-cu mestert egy holdfényes sétára.

– Mit gondoltok – kérdezte Ma-cu –, mire lehetne legjobban kihasználni ezt az időt?

– A szövegek tanulmányozására – szólalt meg elsőnek Hszi-tang.

– Kiváló alkalom az elmélkedésre – javasolta Paj-csang.

Ilyen válaszok hallatán Nan-csüan megfordult, és faképnél hagyta őket.

– A szövegeket meghagyom Hszi-tangnak – mondotta a mester –, Paj-csang pedig valóban tehetséges elmélkedő. De Nan-csüan lépett túl a hívságokon.

Nan-csüan Pu-jüan (Vang mester), 748-834/5

Az írástudó Csang-cso tiszteletét tette Hszi-tang mesternél:

– Léteznek-e a hegyek, a folyók és maga a nagy föld? – kérdezte tőle.

– Léteznek – felelte Hszi-tang.

– Nem igaz!

– Melyik csan mesterrel találkoztál?

– Csing-san mesternél jártam, és bármiről kérdeztem, azt mondta, hogy nem létezik.

– Van családod?

– Feleségem és két gyermekem.

– Milyen családja van Csing-sannak?

– Csing-san egy öreg buddha – háborodott fel az írástudó –, ne rágalmazd őt, mester!

– Ha valaha olyan családi állapotba kerülsz, mint Csing-san, akkor majd én is azt mondom, hogy nem léteznek.

Csang-cso fejet hajtott.