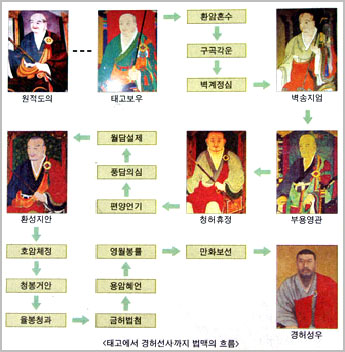

ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

명적도의 / 明寂道義 Myeongjeok Doui (?-825)

(Magyar átírás:) Mjongdzsok Toi

Myeongjeok Doui (? ~ ?)

http://www.koreanbuddhism.net/master/priest_view.asp?cat_seq=10&priest_seq=17&page=1

Inheritor of the core teachings of the Southern School of Chan Buddhism, (Kr. Seon; Jp. Zen) derived from Master Huineng, the sixth Patriarch, Doui Guksa was the first to bring these teachings to Korea and stands as the founder of the Order of Korean Buddhism.

1. Career

The lifeworks of Master Doui are made available to us based on the records of the “Doui Jeon” (Biography of Doui), in the 17th Volume of the Jodangjip (Records of the Ancestral Hall). According to the “Doui Jeon,” Master Doui lived in Myeongju, the present day Gangneung in Gangwon-do Province. His name upon entering the sangha was Myeongjeok and his Buddhist title was Doui. He was born in Bukhan-gun, located in present day Seoul, under the surname Wang. Before Doui's birth, his father had a dream of a white rainbow spreading across the sky and entering his room, while his mother dreamt of sleeping together with a monk. Upon waking from their dreams, his parents found the room to be filled with a mysterious fragrance. About a half-month later, the signs of pregnancy arrived, but the baby was only to arrive after a 39-month gestation period. Around evening on the day of the Master's birth, a mysterious monk suddenly appeared at the front door, holding a staff and stating the following command: “Place the umbilical cord of the baby born today at the hill by the riverside,” before he disappeared without a trace. Upon Master Doui's parents following the advice of the monk and burying the afterbirth in the ground, some large deer came to stand guard over that spot. Though the sun continued to rise and fall, the deer never left, and though the animals saw many people visit the site, the deer did not harm them. The Buddhist name that Master Doui received upon entering the sangha, Myeongjeok, meaning “clear quiescence,” originates from the scene depicted in this story.

In 784 A.D., the fifth year of King Seondeok's reign, Master Doui crossed the sea to visit the Tang Dynasty with ambassadors Han Chan-ho and Kim Yang-gong. Upon their arrival, he immediately went to Mt. Wutaishan whereupon he received a divine vision from the Bodhisattva Manjusri. Following this experience, and after visiting many other regions, he went to Baotan Temple in Guangfu, where he took the full monastic precepts. He then went to Mt. Caoxi (Kr. Mt. Jogye) in Guandong Province to pay homage to the shrine of Huineng, whereupon he had a most mysterious experience. On his arrival, the door to the shrine opened of its own accord, and after he bowed three times in obeisance, the door then closed again on its own.

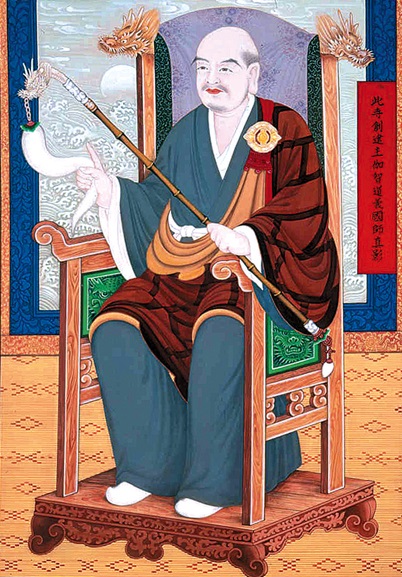

Following this, Master Doui received instructions on meditation from Master Xitang Zhizang (서당지장 / 西堂智藏 735~814) at Kaiyuan Temple in Hongzhou, Jiangxi Province. As a disciple studying under Master Mazu Daoyi, Master Xitang Zhizang was the pre-eminent Chan monk of his age. In order to request Xitang Zhizang to become his master, he had to unravel the bundle of doubts that hindered him, until he finally bore through the obstacles blocking his progress. Seeing him overcome this struggle, Master Xitang Zhizang was overjoyed, as if finding a beautiful jewel in the rough or a pearl within an oyster, saying, “truly, if I cannot transmit the dharma to a man like this, there is nobody I could transmit it to.” He then renamed the Master with the appellation “Doui” (“Path of Righteousness”). Subsequently, Master Doui set out on the path of purification and went in search of the dwelling place of Master Baizhang Huaihai (749~814) at Mt. Baizhangshan to study under his tutelage. Much impressed with him, Master Baizhang is said to have lamented, “the entire Chan lineage of Mazu Daoyi is returning to Silla!”

In 821 CE (the 13th year of King Heondeok), Master Doui returned to Silla to propagate the teachings of the Chinese Southern Chan School. However, as the tradition of Scholastic (or Doctrinal, gyo) Buddhism had become firmly entrenched within Silla at that time, people looked upon Master Doui’s Seon method as rather absurd. Accordingly, judging that the circumstances were not yet ripe for the acceptance of his teachings, Master Doui retired from the world to Jinjeon-sa Monastery in Mt. Seoraksan, where he cultivated a line of disciples. In this way, his Seon method passed through his disciple Yeomgeo and bloomed in the next generation through his dharma grandson Master Chejing (804-880), leading to the establishment of the Gajisan school, one of the Nine Mountain Seon schools of the Goryeo period.

2. Doctrinal Distinction

Because no detailed materials or writings were passed down, it is difficult to definitively grasp the Seon doctrine of Master Doui. However, from the glimpses of his thought that we are able to catch from materials such as the memorial inscriptions of his disciples, as well as the knowledge that the Master’s doctrine is linked to the lineage of sixth Patriarch Huineng’s teachings, we can assume they followed the lines of the Southern Chan School of Buddhism.

In continuation with the dharma taught by Master Doui, the writings of Chejing, founder of the Gajinsan School, express the Master’s Seon doctrine as “the tenet of unconditioned spontaneity.”

In Chan teachings, the idea of “unconditioned spontaneity” refers to the way of life of following one’s original mind as it is, devoid of attachment or entanglement within the totality of existence, transcending the law of life and death, without any contrived artificiality of discriminating thought. Master Mazu, coining the term for this original mind as “ordinary mind,” asserted that “ordinary mind is precisely the way in which truth naturally functions.” Namely, if the original mind is not lost and all matters are allowed to take their course according to each situation, all things would be real and truthful and exist without contrived artificiality or entanglement. This idea is indicative of a religion of everydayness, seeking the development of a sincere life within the ordinary confines of humanity’s day-to-day existence.

In addition, we can also discern something, however fragmentary, of Master Doui’s notion of “unconditioned spontaneity” from the dialogue between him and the Head Monk Jiwon (Seungtong) of the Hwaeom School, as introduced in the Seonmun Bojangnok compiled by the Goryeo era monk, Cheonchaek.

The contents of this dialogue can largely be divided into two parts. The first part is a criticism of Scholastic Buddhism. Criticizing that Scholastic Buddhism, bound in its own dogma, was unable to ascertain the fundamental basis of the mind’s essence, Master Doui denied the tenet of the “Four Dharma Realms” as well as the "teachings of the fifty-five sages," written in the Huayan (Kr. Hwaeom) Sutra, the basis of the Hwaeom School. In addition, he emphasized that it is only within the conditions of the immediate moment that we should look to see our own nature. The second part pertains to the establishment of the Mind-seal Dharma of the Patriarchs. In establishing his idea of the Mind-seal of the Patriarchs, Master Doui speaks about the system of cultivation based on “faith, discernment, performance, and assurance” to address the Patriarchal Seon tenet of “no thought, no practice” as follows.

“The rationality behind ‘no thought, no practice’ is nothing more than the concept of ‘faith, interpretation, performance, and evidence.’ The wisdom of the dharma taught by the Patriarch School, that does not distinguish between the ‘Buddha’ or ‘sentient beings,’ is nothing but the direct realization of the fundamental truth of reality. As a result, the Mind-seal dharma of the Masters was transmitted separate from the Five Teachings of the Hwaeom School. The reason behind the appearance of the Buddha’s material form is nothing more than an expedient means, a temporary apparition conjured for the sake of those who are unable to understand the true principles of the Patriarchs. Even though one were to spend many years reading the sutras, if that was the method one were to utilize in pursuit of realizing the Mind-seal Dharma of the Patriarchs, the goal would be difficult to obtain even if an eon were to pass.” (from the dialogue between Master Doui and Jiwon Seungtong)

The “no thought theory” mentioned here refers to the undeluded and essential original mind, using the representative doctrine of the Southern Chan School as advocated by Huineng and his disciple Heze Shenhui (684~758).

The notion of “no practice” is the idea that there is no requirement for practice on the path to enlightenment. This is a refutation of the practices that seek to perceive the mind through artificial meditation or to perfect oneself on the path of gradual cultivation. Like other Chan theories, the “no practice theory” was already elucidated by Huineng and had been well developed and widely accepted, owing to the efforts of successive generations of great masters of Patriarchal Chan, including Shenhui, Mazu, Baizhang, Huangbo, and Linji, among others.

As such, we can see how in emphasizing the “no thought, no practice” theory that joins the ideas of Mazu’s “ordinary mind” and Shenhui’s “no thought theory,” Master Doui’s core tenet of “unconditioned spontaneity” is tied to the traditional thought of the Southern Chan School.