ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

天童如净 Tiantong Rujing (1163–1228)

(Rōmaji:) Tendō Nyōjo

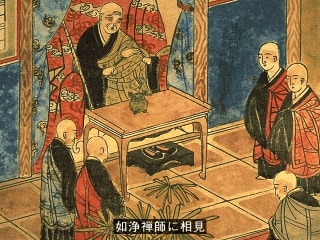

Rujing & Dōgen

Tiāntóng Rújìng (天童如淨; Japanese: Tendō Nyōjo) was a Caodong Buddhist monk living in Qìngdé Temple (慶徳寺; Japanese: Keitoku-ji) on Tiāntóng Mountain (天童山; Japanese: Tendouzan) in Yinzhou District, Ningbo. He taught and gave dharma transmission to Sōtō Zen founder Dōgen as well as early Sōtō monk Jakuen (寂円 Jìyuán).

His teacher was Xuedou Zhijian (雪竇智鑑, 1105–1192), who was the sixteenth-generation dharma descendant of Huineng.

He is traditionally the originator of the terms shikantaza and shinjin-datsuraku ("casting off of body and mind").

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/RujingTendō Nyojō (天童如淨)

C. Tiantong Rujing. 1163-1228. A Chinese monk, dharma heir to Sokuan Chikan 足庵智鑑 in the Soto lineage, and abbot of the Keitoku (C. Jingde) Monastery on Tendō (C. Tiantong) Mountain when Dōgen was in training there. Rujing had six dharma heirs, one of whom was Dōgen.

http://global.sotozen-net.or.jp/eng/library/glossary/individual.html?key=tend_nyoj

TIANTONG RUJING

by Andy Ferguson

In: Zen's Chinese Heritage: The Masters and Their Teachings , Wisdom Publications, 2011, pp. 492-493.

TIANTONG RUJING (1163–1228) was a disciple and Dharma heir of Zu’an Zhijian. Rujing came from the city of Weijiang in ancient Mingzhou (near modern Ningbo City in Zhejiang Province). During his life he lived at a succession of famous temples including Qingliang Temple at Nanjing and Jingzi Temple on the south edge of West Lake in Hangzhou. He eventually resided at Tiantong, where he taught and transmitted the Buddhadharma to the famous Japanese monk Eihei Dogen. The Record of Rujing reveals Dogen’s teacher to be among the most poetically expressive of all the Zen ancients. He effused his Dharma talks with wonderful natural allusions and poetry of the highest order. The following passages are from The Record of Rujing.

Once, when sitting in his abbot’s quarters, Zen master Tiantong Rujing said, “Gouge out Bodhidharma’s eyeball and use it like a mud ball to hit people!”

Then he yelled, “Look! The ocean has dried up and the ocean floor is cracked! The billowing waves are striking the heavens!”

Rujing addressed the monks, saying, “This morning is the first day of spring. The poetry of the pomegranate blossoms enters its samadhi. How can such words be expressed?”

Rujing lifted his whisk and said, “Witness a single red speck of the myriad karmic streams! The spring colors that move us need not be many.”241

Rujing entered the hall and said, “The willows are adorned with waistbands, and plum blossoms fall onto your sleeves. You catch a glimpse of the orioles. Dance like the great wind!”

Then Rujing said, “Whose realm is this? At the foot of the Jingzi Temple gate—the heads of tuber plants appear.”

Zen worthies from all directions assembled at Qingliang Temple [a temple in Nanjing City where Tiantong then resided as abbot].

Tiantong addressed them, saying, “The great way has no gate! It jumps off the heads of you Zen worthies who have assembled from every direction. Emptiness is without a path. It goes in and out of the nostrils of the host of Qingliang Temple. Attendees here today are the thieving descendants of the Tathagata—the calamitous offspring of Linji!

“Aiyee! Everyone is dancing crazily in the spring wind. The apricot blossoms have fallen and the red petals are scattered on the breeze!”

Zen master Tiantong Rujing entered the hall. Striking the ground with his staff he said, “This is the realm of vertical precipice.”

Striking the floor again he said, “Deep, profound, remote, and distant. No one can reach it.”

He struck again and said, “But supposing you could reach this place, what would it be like? Aieee! I smile and point to the place where apes call. There is yet another realm where the numinous traces may be found.”

Tiantong addressed the monks, saying, “Thoughts in the mind are confused and scattered. How can they be controlled? In the story about Zhaozhou and whether or not a dog has buddha nature, there is an iron broom named ‘Wu.’ If you use it to sweep thoughts, they just become more numerous. Then you frantically sweep harder, trying to get rid of even more thoughts. Day and night you sweep with all your might, furiously working away. All of a sudden, the broom breaks into vast emptiness, and you instantly penetrate the myriad differences and thousand variations of the universe.”

Tiantong addressed the monks, saying, “The clouds mindlessly drift past the mountain cliffs. Four years ago, or just yesterday, is today. In due course, water returns to its source. Four years hence, or just today, is yesterday.”

Tiantong then raised his whisk and moved it in a great circle, saying, “If I must present this to you here, then I say that every year is a good year. Every day is a good day. So tell me, how can this be verified? Where clouds and water meet they laugh ‘Ha, Ha!’ Their laughter spontaneously fills the wind and sunlight.”

Ju-ching's death poem

In: DOC: The Zen Poetry of Dogen. Verses from the Mountain of Eternal Peace

by Steven Heine

Tuttle Shokai Ltd., Charles E Tuttle. 1997

For sixty-six years

Committing terrible sins against heaven,

Now leaping beyond,

While still alive, plunging into the Yellow Springs;

Amazing! I used to believe that

Life and death were unrelated.Cf.

The sins I have committed

in the sixty-six years of my life

fill the universe:

as I beat myself,

I drop into Hell alive.Tr. of Takashi James Kodera

Tiantong Rujing (gouache) by Kōkyō Henkel

天童山景德寺如淨禪師續語錄 Tiantongshan Jingdesi Rujing Chanshi Xu Yulu / Tendōsan Keitokuji Nyojō Zenji Zoku Goroku

PDF: Tiantong Mountain, Jingde Temple, Chan Teacher Rujing’s Continuing Record of Sayings

Translated by Yashu Zhang and Kōkyō Henkel

Sayings of Master Rujing of Tiantong

Translated by Thomas Cleary

In: Timeless Spring, A Soto Zen Anthology,

Weatherhill / Wheelwright Press, Tokyo - New York, 1980,

pp. 25-26, 91-94.

Rujing (1163-1228), a contemporary of Wansong Xingxiu

萬松行秀 (1166-1246), was another famous chan master

who served as teaching abbot of several of the public monasteries,

but it was not known who his ehan teacher was until at

the end of his life he revealed that he had acknowledgement

of the transmission from Xuedou Zhijian 雪竇智鑑 (1105-1192),

a descendant of Danxia Zichun 丹霞子淳 (1064-1117).

Rujing's practice was just sitting; he lived in a monastery

from the age of nineteen, gave up the study of scriptures,

never returned to his native place, never spoke to the vil-

lagers, not even to people next to him in the monk's hall,

didn't go to any of the various halls and rooms but just sat

in the monks' meditation hall, vowing to wear out a dia-

mond seat. He said, "No more need to burn incense, make

prostrations, invoke buddhas, perform repentence cere-

monies, or read scriptures - just sit and liberate mind and

body."

(pp. 25-26)*

Rujing lived from 1163 to 1228 and served as abbot and teachmg

master at several large public monasteries; it was at TIantong in

eastern China that Dogen met Rujing. who was to become the

final human teacher and greatest spiritual benefactor of young

Dogen. Rujing was descended from the great Cao Dong masters

Furong Daokai 芙蓉道楷 (1042-1118)) and Danxia; it was he who

taught Dogen the technique of 'just sitting', which he used to

practice together with the community in the great meditation halls.

The following talk about sitting meditation is taken from the Hokyoki,

Dogen's record of private talks with Rujing; the general talk and the

eulogies are from records of Rujing's sayings compiled by other disciples.

(p. 91)*

Although saints and self-enlightened sages do not become

attached to their experience in sitting meditation, they lack

great compassion; therefore they are not the same as the

buddhas and patriarchs, who considered great compassion

foremost and sat in meditation with the vow to save all

sentient beings. The outsiders in India also sat in medita-

tion, but they always had three problems; attachment to

the experience, false views, and conceit-therefore it is

always different from the sitting meditation of the bud-

dhas and patriarchs.Buddhist disciples also had sitting meditation, but their

compassion was weak; they did not penetrate the real

character of all things with incisive knowledge-only im-

proving themselves, they cut off the lineage of buddhas;

therefore theirs is always different from the sitting medita-

tion of buddhas and patriarchs.What I mean to say is that buddhas and patriarchs, frorr

their very first inspiration, sit in meditation with the vow

to gather together all the qualities of buddhahood; there

fore in their sitting meditation they do not forget sentient

beings, do not forsake sentient beings - they always have

loving thoughts even for insects, and vow to rescue them.

Whatever virtures they have, they dedicate to all; therefore

the buddhas and patriarchs are always in the world of de-

sire practicing meditation and working on the way. In the

world of desire only this world provides the best situation;

cultivating all virtues life after life, one attains to gentility

and ease of mind.

GENERAL TALK

Kaaa! People, this shout, though before the ancient bud-

dhas, has already missed the point; how much the more so

to come here today and shout wildly - what kind of fart-

ing this would be. If there is someone who can come forth

boldly to smash this shitty mouth, knock out my teeth and

stuff them in a shit hole, you can avoid seeing me fooling

people with a lot of confusion.But even this is still raising your fist behind someone's

back, raising your voice to stop an echo; yet we set up

many gates, to open up a single road - isn't there anyone

who will come forth?(A long silence) If there is no one, then I will use a shout

for the moment to pile up confusion and fool you people.

Kaaa! Here there is host and guest, illumination and func-

tion; do you know where it ultimately ends up? If you

realize where it ends up, you know where it arises; if you

know where it arises, you know where it passes away. If

you know where it passes away, you then realize that birth

and death both pass away, and ultimate peace appears, in

everyday life, appearing in six places. In the eye it is called

seeing; you must strip off your eyes till you see nothing at

all - then afterwards there is nothing you don't see; only

then can it be called seeing.In the ear it is called hearing; you must block your ears

shut till you hear nothing at all - then afterwards there is

nothing you don't hear; only then can it be called hearing.In the nose it is called smelling; you must smash off

your nostrils till fragrance and stench are not distinguished

- afterwards there is nothing you can't distinguish; only

then can it be called smelling.In the tongue it talks; you must pluck out your tongue,

so heaven and earth are wrapped up in silence - after-

wards it is effulgent and unbroken; only then can it be

called talking.In the body it is called person; you must slough off the

gross elements and not depend on anything - afterwards

you manifest form in accordance with kind (of being); only

then can it be called person.In the mind it is called consciousness; you must cut off

forever all clinging to objects, so that the three incalculable

aeons are empty - afterwards origin and decease do not

stop - only this can be called consciousness.Appearing as above in these six places, without any gap,

this is what is meant by there being host and guest, il-

lumination and function, as I said before - host and guest

interchange, illumination and function merge. From the

buddhas of the past, present, and future and the six gen-

erations of ancestral teachers above to the animals of vari-

ous species, plants, trees, and insects below, all are this

one shout - none is left out. Then you see that 'before the

appearance of the ancient buddhas' is right now, and right

now is 'before the appearance of the ancient buddhas.'

They are not two, do not have two separate conditions,

because they are not distinct; they are continuous.According to what I am saying, what is there to shout

about or talk about? Basically there is not so much -

everyone should get a beating. What mistake is there?

What is not mistaken? There are even Linji's four shouts;

no harm to move the shoulders while walking - I'll pierce

nostrils one by one for you. Bah! 'One shout is like the

jewel sword of the diamond king' - a toilet sweeper. 'One

shout is like a lion crouching on the ground ' - a rat in its

nest. 'One shout is like a probing pole, shadowing grass'

- a fellow fishing for clams. 'One shout does not function

as a shout' - a ghost in front of a skull. Tonight is clear

and cool; I call this medicine for a dead horse - even if

you can bring this shout to life, how can you avoid the

sound of farting?Even so, tell me, where does it come from, 'before the

ancient buddhas appeared?' Can you be sure? If you can

get it for sure, then nothing's wrong with wild shouting -

you'll avoid seeking it folding your hands at the corner of

a rope seat. If you are not yet thus, though, beware of

misusing your fists and feet. Bah!

VERSE ON LINJI

Making an empty fist,

Threatening the world to death;

Such an ancestral teacher -

An animal, an ass.

VERSE ON AN ANCIENT SAYING

Yunmen said, "The world is so wide - why put on a

seven-strip robe at the sound of a bell?"Rujing said,

At the sound of the bell I put on a dense web;*

The inconceivable function's miraculous powers

Produce a variety of effects.

The thief is a member of the family;

It is necessary to sweep away the tracks -

Only the great peace with no signs

Is really safe and harmonious.* 'Dense web' also alludes to the multitude of appearances of the

phenomenal world. This reading is hardly concealed in the phonetic

transcription for the Sanskrit word for 'upper robe' - i. e . the 7-strip.

FUNERAL SPEECHES

SETTING FIRE TO ELDER YI'S BIER

'All things return to one' - living is like wearing your

shirt; 'where does the one return?' - dying is like taking

off your pants. When life and death are sloughed off and

do not concern you at all, the spiritual light of the one

path always stands out unique. Ah, the swift flames in the

wind flare up - all atoms in all worlds do not interchange.SETTING FIRE TO A DOCTOR'S BIER

The mortal diseases of humans you can heal, but when

you die, who can bring you back to life? I have a simple

method, a handful of fire; I will burn for y ou the medicine

gourd. Someone answers, "I'm alive, revived" - tell me,

how do you prove it? (describing a circle with the fire-

brand) Ah, the original face has no birth or death; spring

is in the plum flowers, entering a painted picture.

TENDÓ NJODZSÓ

Tien-tung Zsu-csing (1163-1228)

In: Zeisler István [Mokushó Szenkú, 1946-1990]: A zen átadása Buddhától Buddháig,

Fordította: Király Attila, Farkas Lőrinc Imre kiadó, 1996, 99-107. oldal

[A fordítások az AZI lapjában a La Revue Zenben 1986-1989 között megjelent cikkek alapján készültek.]

Dógen mester a XIII. században honosította meg Japánban a szótó zent. Buddha tanításának keresésére indult el Kínába, ahol két átbarangolt év után — mely alatt számos kolostorban és mesternél megfordult —találkozott Tendó Njodzsóval, akiben felismerte a hiteles mestert, a valódi Dharma birtokosát. Amikor Dógen a tanítványa lett, Njodzsó azt mondta neki: „Ez az a Dharma, amit a buddhák és a pátriárkák továbbadtak egymásnak; ez az a virág, amelyet Mahákásjapa kapott; a kesza, a buddha ruhája, amelyet a hatodik pátriárkának adtak át, és ez a Sóbógendzó, Az igaz törvény szemének kincse, amely csak az én kolostoromban létezik. Mások még csak nem is álmodhattak róla."

Njodzsó 1163-ban született, és már fiatalon szerzetessé lett. Mondják róla, hogy rendkívül intelligens ember volt, éppen ezért tanítói már nagyon korán a szútrák és a sásztrák tanulmányozása felé irányították. Tizenkilenc éves korában otthagyta a könyveit, és elhatározta, hogy kolostorról kolostorra vándorolva fogja a zent gyakorolni, különböző mesterek irányítása alatt. Végül Szecso Csikantól kapta meg a szótó zen átadását.

A zen Njodzsó idején

Zarándoklata során Njodzsónak alkalma volt megismerkedni a zen ebben az időben létező minden fajtájával. A több mint öt évszázados fejlődés alatt Bódhidharma eredeti zenje elkeveredett más buddhista iskolák tanaival, így aztán iskolák szerint más és más tanítások kerültek előtérbe:

◆ a szabályok és a kolostori fegyelem,

◆ a nenbucu (Amitábha Buddha nevének) recitálása,

◆ a különleges meditációs technikák, például a légzésszámolás,

◆ a taoizmus ismerete, de a neotaoizmusé is, amit „sötét tanításnak" hívtak,

◆ a korszak három legfontosabb filozófiai áramlatának összeolvasztása (buddhizmus, konfucianizmus, taoizmus),

◆ a kóanokra való összpontosítás, a megvilágosodás elérése végett.

Számos iskola ezek közül, hogy biztosítsa sikerét, megpróbálta kiterjeszteni befolyását a kor hatalmasságaira — hivatalnokokra, kormányzókra, a császári udvarra, sőt magára az uralkodóra is.

Fanyar kritikák

Njodzsó élénken bírált mindenféle szektárianizmust, mivel ezek meghamisították az eredeti tanítást. Azt sem engedte meg, hogy a „zen iskola‖ elnevezést használják az eredeti tanításra. Egy nap a következő kijelentést tette:

— A pátriárkák tanítása ma hanyatlóban van. Ez a sok állat egyre csak azt hangoztatja, hogy rengeteg különböző tanítás van. Ez szánalmas. Szükségtelen önkényesen a „zen iskola" elnevezéssel illetnünk a buddhák és a pátriárkák nagy Útját. A zen egy pontatlan és hibás kifejezés, ezt használják ezek a kopasz vadállatok is. Bezzeg a régmúlt idők erényes alakjai előtt nem volt ismeretlen e szó valódi tartalma.

Njodzsó ellene volt annak az elgondolásnak is, amely szerint a buddhizmus megegyezne más tanításokkal:

— Az az elképzelés, amely szerint a három tanítás — a buddhizmus, a taoizmus és a konfucianizmus — egy és ugyanaz, nem éri el még az alsóbb lények makogásának színvonalát sem. Ez Buddha Dharmájának lerombolása. Sajnos, igen elharapódzott ez a nézet. Akik ezt vallják, abban reménykednek, hogy az emberi és az égi lények, a kormányzók és az uralkodók tanítóivá válhatnak, de valójában csak a buddhák és a pátriárkák nagy Útjának összeomlásához járulnak hozzá.

Njodzsó természetesen azokat ostorozta szavaival, akik csak azért vállalkoztak a kolostori életre, hogy a későbbiekben világi sikerekre és elismertségre tehessenek szert:

— Számtalan esetben látni olyanokat, akik minden ok nélkül pátriárkának kiáltják ki magukat. Díszes keszákkal cicomázzák fel magukat, hosszúra növesztik hajukat és körmüket, és a kolostorban betöltött helyükre, mint sikerességük bizonyítékára tekintenek. Siralmas, amit tesznek! Egytől-egyig csak barmok, holttestek a Dharmatiszta óceánjában.

Csak zazen

Njodzsó ezekből az eltévelyedett tanításokból csak a lényeget őrizte meg: a zazent. Ennek védelmében határozottan kijelentette:

—Sikantadza, „csak ülj"!

Egyedül a zazen a buddhák igaz ösvénye, nincs szüksége semmiféle segítségre, hogy megerősítést nyerjen, önmagában teljes és tökéletes: ez minden pátriárka felébredése.

—A legtöbb lehetőséget az Út tanulmányozására a zazen adja — mondta —, e gyakorlat ereje révén érte el minden nagy mester a szatorit. A tanítványnak a sikantadzát kell gyakorolnia, anélkül, hogy ahhoz bármit is hozzátenne.

Élő példája volt tanításának, egész életét — az Út üdvére — a zazen gyakorlásának szentelte.

— Amikor elmúltam tizenkilenc éves — mesélte tanítványainak —, felkerekedtem és bejártam az országot, hogy mestert találjak magamnak, de nem találtam egyetlen egyet sem. Tizenkilenc éves korom óta nem telt el úgy egyetlen nap vagy éjszaka sem, hogy ne gyakoroltam volna a zazent. A szülőföldemen már az ismerőseimmel sem elegyedtem beszédbe, holott ez még jóval azt megelőzően volt, hogy e kolostor elöljárójává tettek meg. Ugyanis képtelen vagyok elviselni az időpocsékolást. Nem éltem másutt, csak templomokban, nem tettem be a lábamat soha más lakhelyre. Sohasem fecséreltem időt arra, hogy kedvtelésből hegyi tájakra vagy a tenger partjára kirándulgassak. A zazenre kijelölt órákon túl nyáron a hűsebb helyeket, télen a legkevésbé hideg helyeket kerestem fel, mert addig akartam gyakorolni a zazent, míg a legmélyére nem jutok.

Buddha testtartását mindvégig követendő példaként őriztem a tudatomban. Amikor aranyértől szenvedtem, még nagyobb elszántsággal gyakoroltam a zazent.

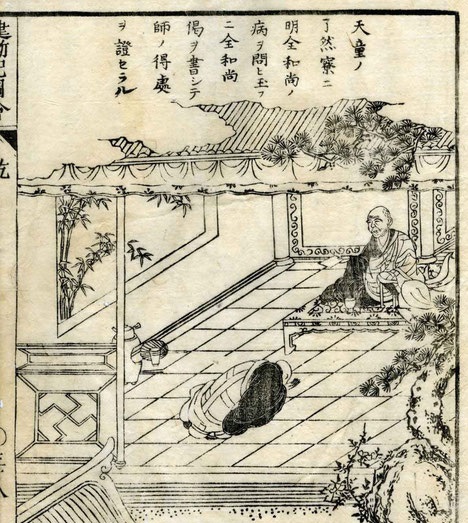

Njodzsó és tanítványai

Bele akarta sulykolni tanítványai testébe és tudatába a sikantadzában való hitet, ezért Njodzsó saját magát sem kímélte. Rendkívüli szívós volt: csak éjfél előtt hagyta el a dódzsót, és másnap hajnali három óra tájban már vissza is tért oda a zazent gyakorolni. Ha a szerzetesek elaludtak a gyakorlat alatt, felállt a helyéről és rájuk csapott az öklével vagy a sarujával. Néha abba-hagyatta a zazent, össze-hívta őket egy másik teremben, és beszédet intézett hozzájuk:

—Minek jöttetek ebbe a kolostorba, ha az időt alvásra pazaroljátok? Ezért hagytátok el otthonotokat és lettetek szerzetesek? Azt hiszitek talán, hogy ezen a világon lehetőségetek nyílik a könnyed életre? Az élet és a halál eleven kérdések, ez az állandótlan világ gyorsan tovatűnik; akár már ma este vagy holnap reggel is megtámadhat egy betegség, vagy elragadhat a halál. Ilyen körülmények között teljesen értelmetlen dolog alvással tölteni az időt a Buddha Dharmájának gyakorlása helyett. Amikor a Törvény — a buddhista tan — még virágzott ebben az országban, a szerzetesek csak a zazenre figyeltek. Éppen azért van hanyatlóban manapság a Dharma, mert ma már nem buzdítják erre őket.

Ezen intelmek ellenére, egy alkalommal egyik segítője, a szerzetesek gyakori fáradtságát látva úgy ítélte, hogy a zazenek túlságosan hosszúak és megerőltetőek, ezért tiszteletteljesen azok lerövidítésére kérte Njodzsót. — Szó sem lehet róla — mondta Njodzsó –, akik nem rendelkeznek az Út szellemiségével, el fognak aludni akkor is, ha a zazen rövidebb. Minél hosszabb a zazen, annál nagyobb azoknak az öröme, akik szilárd elhatározással jöttek ide, és akiknek birtokában van az Út szellemisége.

E kemény rendszer ellenére sokan siettek ide az ország minden tájáról, hogy az ő oldalán gyakorolhassanak. Ha őszinte akarattal és buzgalommal jöttek, a mester melegen fogadta őket, mint apa a fiát. Függetlenül attól, hogy bódhiszattvákról, világi hívőkről vagy novíciusokról volt szó, mindenkit egyformán szerzetesként kezelt. De elutasította és elküldte azokat, akik nem mondhatták magukénak a bodai sint, az Út szellemiségét.

—Felesleges beengedni azokat, akikből hiányzik az őszinteség — mondta —, hiszen csak zavarnák a többieket. Ezért nem engedhetem meg, hogy a kolostorban maradjanak.

Njodzsó mester tiszta zenje

Njodzsó élete végéig visszautasított minden kitüntetést és elismerést, és soha sem fogadott el pénzt. A császárnak is visszaküldte a neki felajánlott lila keszát. Dógen egy napon azt kérdezte tőle:

—Tisztelendőséged miért nem veszi fel sosem a mesternek járó keszát?

—Amióta egy kolostorért vagyok felelős, nem hordok ilyen keszát — hangzott felelete —, azt hiszem, talán azért, hogy megőrizzem az egyszerűségemet. De azért is, mert a Buddhának és a tanítványainak sem volt semmijük néhány rongyon és csorba csészén kívül.

— A többi mester mind hordja — mondta Dógen —kétségkívül kapzsiságból. Azonban az öreg Vansi buddha is hordta. Talán hiányzott belőle az egyszerűség?

— Amikor az öreg Vansi buddha ezt a keszát viselte —mondta Njódzsó, egyszerű volt, és megmaradt az Út követőjének. Én azért nem hordom ezt a keszát, hogy ne kelljen alkalmazkodnom korunk mestereinek gyakorlatához. Téged azonban semmi sem akadályoz meg abban, hogy a szülőhazádban, Japánban ezt viseld.

Njodzsó számára csak a zazen a határtalan útja. Elnyerni az emberi létformát nem is remélt szerencse, a zazen gyakorlása pedig még egy ezt is felülmúló, határtalan áldás. A zazenbe — amely maga Isten vagy Buddha —vetett bizalommal és hittel egy hiteles élet teremtődik. Az erre való összpontosítás maga az egyetemes szeretet, amely nem másból, mint az Út mély szeretetéből fakad.

Njodzsó egy nap így fordult tanítványaihoz:

— Immáron betöltöttem a hatvanadik életévem, ezért a zazen gyakorlása komoly nehézséget jelent számomra. A tanításotok miatt néha végig kell vágnom rajtatok a botommal, bár én ezt mindennél jobban gyűlölöm. Csak azért teszem ezt, mert a buddha helyén vagyok. Kérlek, bocsássatok meg nekem ezért. Csak azért maradok e helyen, hogy a Buddha Útjára és Dharmájára tanítsalak benneteket, a többi kolostorok mesterei ugyanis nem tudnak semmit sem ezekről.

Egy évvel később, a halála előtt Njodzsó megírta utolsó versét:

Hatvan év alatt bűneim

Elárasztották a világot.

A test, amelyet a legmagasabbra emeltem fel,

Most visszasüllyed a pokolba.

Ó! Nincs semmi mondandóm

Az életről és a halálról.Vö. Végh József fordításával:

六十六年,

罪犯彌天;

打個蹦跳,

活陷黃泉。

咦從來生

死不相干。„Hatvanhat évnyi

Bűn az Ég ellen!

Ezt átugorva,

Bucskázom még élőn

A Sárga Forrásba:

Hol lét s halál összevész!”

Njodzsó mester tanbeszéde

Noha a szentek és a bölcsek zazenje felülemelkedik minden ragaszkodáson, hiányzik belőle a nagy együttérzés. Ezért különbözik a buddhák és a pátriárkák zazenjétől —mert ők csak azért gyakorolnak, hogy megmentsenek minden érző lényt.

Az indiai eretnekek is gyakorolják a zazent, de sohasem képesek megszabadulni a ragaszkodástól, a téves nézetektől és a dölyfösségtől. Zazenjük örökké különbözik a buddhák és a pátriárkák gyakorlatától.

Néhány önző tanítvány is gyakorolja a zazent, de azt nem itatja át az együttérző szeretet. Személyes bölcsességük nem teszi lehetővé számukra, hogy megértsék a jelenségek valódi jellegét. Csak a saját tökéletesítésük érdekében gyakorolnak, és így megszakítják az átadás vonalát. Zazenjük örökké különbözik a buddhák és a pátriárkák gyakorlatától.

Amikor a buddhák és a pátriárkák leülnek zazenbe, rögtön az első napon fogadalmat tesznek a világmindenség egyesítésére. Egyetlen érző lényről sem szabad megfeledkezni, vagy őt cserben hagyni.

Együttérző tudatuk egészen a rovarokig hatol, a zazen érdemeit tudatosság nélkül nyújtják feléjük, hogy az üdvükre válhasson.

Éppen ezért, a buddhák és a pátriárkák csak a vágy birodalmában gyakorolják a zazent. Örökkévalóan folytatják azt, és így elérik a tudat gyöngédségét.

— Mi a tudat gyöngédsége? — kérdezte Dógen.

Njodzsó így felelt:

— A tudat gyöngédsége a buddhák és a pátriárkák fogadalma a test és a tudat elhagyására. Ez a jel van bevésve a buddhák és a pátriárkák szívébe.

Dógen hatszor borult le.