ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

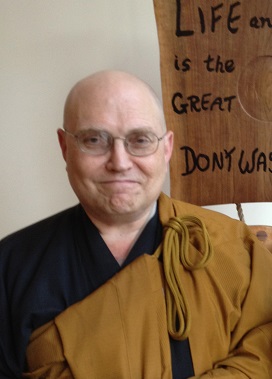

Taigen Dan Leighton (1950-)

Dharma name: 太源砥山 Taigen Shizan

Taigen Dan Leighton is a Soto Zen priest and Dharma successor in the lineage of Shunryu Suzuki Roshi. Taigen first studied Buddhist art and culture in Japan in 1970, and began formal everyday zazen and Soto practice in 1975 at the New York Zen Center with Kando Nakajima Roshi. This led to his returning to graduate in East Asian Studies and study Japanese language at Columbia College. Through the 70s Taigen was also an award-winning documentary film editor in New York and San Francisco, including work for NBC News and Bill Moyers Journal. While editing TV news, it was necessary for Taigen to learn about the one who is not busy. Taigen left his filmmaking career in 1979 to work full time for the San Francisco Zen Center at the Tassajara Bakery, and he was ordained in 1986 by Reb Anderson Roshi.

Taigen practiced and resided for years at San Francisco Zen Center, Tassajara monastery, and Green Gulch Farm Zen Center. He also practiced for two years in Kyoto, Japan, 1990-92, translating Dogen with Rev. Shohaku Okumura, and practicing with several Japanese Soto Zen teachers, including one monastic practice period. Taigen founded the Mountain Source Sangha meditation groups in Bolinas in 1994, then added branches in San Rafael and San Francisco. He received Dharma Transmission in 2000 from Reb Anderson.

Taigen is author of Zen Questions: Zazen, Dogen, and the Spirit of Creative Inquiry, Faces of Compassion: Classic Bodhisattva Archetypes and Their Modern Expression, and Visions of Awakening Space and Time: Dogen and the Lotus Sutra. He is co-translator and editor of several Zen texts including: Dogen's Extensive Record; Cultivating the Empty Field: The Silent Illumination of Zen Master Hongzhi; The Wholehearted Way: A Translation of Dogen's "Bendowa" with Commentary; and Dogen's Pure Standards for the Zen Community: A Translation of "Eihei Shingi". He has also contributed articles to many other books and journals.

Taigen teaches online at the Berkeley Graduate Theological Union, from where he has a Ph.D., and he has taught at Saint Mary's College, the California Institute of Integral Studies, University of San Francisco, University of Creation Spirituality, and in Chicago at Meadville Lombard Theological Seminary and most recently at Loyola University Chicago. Taigen was an elected member of the Board of San Francisco Zen Center, which he Chaired for three years. He has been active in many interfaith dialogue programs, including conducting Buddhist-Christian dialogue workshops, and he also has studied Native American spiritual practice. Taigen has long been active in various Engaged Buddhist programs for social justice, including Peace and Environmental activism and work against the Death Penalty. He is on the International Advisory Council of Buddhist Peace Fellowship.

At the beginning of 2007 Taigen relocated to Chicago, and now is resident Dharma Teacher for Ancient Dragon Zen Gate. He lives with his wife in the north side of Chicago, and enjoys the lively cosmopolitan qualities of Chicago. Through our sangha, Taigen works to develop accessible practice and training programs in the Chicago area.

Cf. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taigen_Dan_Leighton

Curriculum Vitae: https://www.academia.edu/38796295/CV_TDL

Teachings: https://www.ancientdragon.org/taigen-teachings/

佛祖正傳菩薩大戒血脈

Busso shōden bosatsu daikai kechimyaku

The Bloodline of the Buddha’s and Ancestors’ Transmission of the Great Bodhisattva Precepts

永平道元 Dōgen Kigen (1200-1253)

孤雲懐奘 Koun Ejō (1198-1280)

徹通義介 Tettsū Gikai (1219-1309)

螢山紹瑾 Keizan Jōkin (1268-1325)

峨山韶碩 Gasan Jōseki (1275-1366)

太源宗真 Taigen Sōshin (?-1371)

梅山聞本 Baizan Monpon (?-1417)

恕仲天誾 Jochū Tengin (1365-1437)

眞巖道空 Shingan Dōkū (1374-1449)

川僧慧濟 Sensō Esai (?-1475)

以翼長佑 Iyoku Chōyū

無外珪言 Mugai Keigon

然室輿廓 Nenshitsu Yokaku

雪窓鳳積 Sessō Hōseki

臺英是星 Taiei Zeshō

南甫元澤 Nampo Gentaku

象田輿耕 Zōden Yokō

天祐祖寅 Ten'yū Soen

建庵順瑳 Ken'an Junsa

朝國廣寅 Chōkoku Kōen

宣岫呑廣 Senshū Donkō

斧傳元鈯 Fuden Gentotsu

大舜感雄 Daishun Kan'yū

天倫感周 Tenrin Kanshū

利山哲禪 Sessan Tetsuzen

富山舜貴 Fuzan Shunki

實山默印 Jissan Mokuin

湷巖梵龍 Sengan Bonryū

大器敎寛 Daiki Kyōkan

圓成宜鑑 Enjo Gikan

祥雲鳳瑞 Shōun Hōzui

砥山得枉 Shizan Tokuchu

南叟心宗 Nansō Shinshū

觀海得音 Kankai Tokuon

古仙倍道 Kosen Baidō

逆質祖順 Gyakushitsu Sojun (187?-1891)

佛門祖學 Butsumon Sogaku (1858-1933) [Suzuki Shunryū's father; Gyokujun So-on's master]

玉潤祖温 Gyokujun So-on (1877-1934)

祥岳俊隆 Shōgaku Shunryū (1904-1971) [鈴木 Suzuki]

禪達妙融 Zentatsu Myōyū (1936-) [Richard

Baker]

天眞全機 Tenshin Zenki (1943-) [Reb Anderson]

太源砥山 Taigen Shizan (1950-) [Dan Leighton]

PDF: Dōgen’s Appropriation of Lotus Sutra Ground and Space

by

Taigen Dan Leighton

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 32/1, pp. 85-105, © 2005 Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture

PDF: Zazen as an Enactment Ritual

by Taigen Dan Leighton

In: Zen Ritual: Studies of Zen Buddhist Theory in Practice, 2008, Chapter 5, pp. 167. ff.

http://www.mtsource.org/articles/Zen_as_Enactment.htm

Dharma Talks by Taigen Dan Leighton

- The Practice of Genjokoan

Clouds in Water Zen Center - January 8, 2006- Persons of Suchness: How Does it Feel, Being in these Times?

San Francisco Zen Center - March 26, 2005- The Clarity Beyond Clarity of Active Buddhas

Udumbara Sangha - May 30, 2004- Presence of Vow

Mt. Source Sangha, Bolinas - January 10, 2004- Speak Softly, Speak Softly

Green Gulch Zen Center - July 20, 2003- Practice Realization Expression

Green Gulch Farm - May 18, 2003- Zazen as Inquiry

Mt. Source Sangha, Bolinas - January 11, 2003- Zazen as Inquiry

Mt. Source Sangha, Bolinas - January 11, 2003- Enlightenment Day

Mt. Source Sangha, Bolinas - December 12, 2002- Just This is It

Mt. Source Sangha, Bolinas - March 9, 2002- Dropping off Body-Mind, and the Pregnant Pillars

Mt. Source Sangha, Bolinas - Febuary 9, 2002- Taking Refuge / Householder Ordination

Mountain Source Sangha - January 5, 2002- "Evil" in Buddhism

Mt. Source Sangha, Bolinas - October 6, 2001- Consumerism and the Precepts

Green Gulch Farm - September 9, 2001- Bodhichitta: The Mind of Awakening

Hartford Street Zen Center - September, 1997- Liberation and Eternal Vigilance

Green Gulch Farm - July 3, 1994

Articles by Taigen Dan Leighton

Essays and Articles

by Taigen Dan Leighton

http://www.mtsource.org/articles.html

"Meeting Our Ancestors of the Future"

Published in "Shambhala Sun," September, 1996, as "Now is the Past of the Future."Dogen's Appropriation of Lotus Sutra Ground and Space

published in "Japanese Journal of Religious Studies," vol. 32, no. 1, 2005."Sacred Fools and Monastic Rules: Zen Rule-Bending and the Training for Pure Hearts"

from the book, PURITY OF HEART AND CONTEMPLATION: A Monastic Dialogue Between Christian and Asian Traditions , edited by Bruno Barnhart and Joseph Wong. Reprinted by permission of The Continuum International Publishing Group.Huayan Buddhism and the Phenomenal Universe of the Flower Ornament Sutra

From the fall 2006 "Buddhadharma" magazine"Unalienable Rights, Mahayana Inclusivity, and Right Livelihood"

Article for the Journal " Bridges: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Theology, Philosophy, History, and Science " Volume 13, number 3/4; Fall/Winter 2006; "The Value of Buddhism for Contemporary Western Society"Power and Love in the Intermediate Realm:

Buddhist Reflections on "Ghost."

From the book of essays, There is No Spoon: Buddhism at the Movies, edited by Michael Wenger, forthcoming from Wisdom PublicationsZen and the Art of Teaching:

Buddhist Reflections on "Searching for Bobby Fischer"

From the book of essays, There is No Spoon: Buddhism at the Movies, edited by Michael Wenger, forthcoming from Wisdom Publications"Hongzhi, Dogen and the Background of Shikan taza"

Preface to The Art of Just Sitting , edited by Daido Loori, Wisdom Publications, 2002.Buddhism in the West and Liberation as Eternal Vigilance

From a forthcoming issue of "Dharma World" magazine, published in Japan, © Kosei Publishing Company"American Buddhist Values and the Practice of Enlightened Patriotism "

from the Fall, 2004 "Turning Wheel," the journal of the Buddhist Peace Fellowship."In Praise of Bodhisattva Vows "

Article for a book on Bodhisattva Vows; to be published in Germany, and in German, 2002."Reflections on Translating Dogen "

Published in "Dharma Eye" Journal of the Soto Zen Education Center, © 2000"Dogen's Cosmology of Space and the Practice of Self-fulfillment"

Excerpted from the forthcoming "Pacific World" journal"Dylan And Dogen Masters of Spirit and Words"

with Steven Heine

Published in "Kyoto Journal," No. 39, 1999"An Introduction to Skillful Means"

"The Lotus Sutra as a Source for Dogen's Discourse Style "

Paper for an academic conference on "Discourse and Rhetoric in the Transformation of Medieval Japanese Buddhism"

-held at Green Gulch Farm, Fall, 2001

Dōgen's Approach to Training in

Eihei kōroku

Taigen Dan Leighton

Chapter 5, in: Dogen: Textual and Historical Studies. Edited by Steven Heine - Editor. Oxford University Press. New York. 2012

Introduction to Eihei kōroku

Dōgen's Shōbōgenzō is rightly celebrated for its playful, elaborate essays, with their intricate poetic wordplay and evocative philosophical expressions. Dōgen's other major and massive work, Eihei kōroku , has been less well known. The first seven of the ten volumes of Eihei kōroku consist of 531 usually brief jōdō (literally “ascending the hall”), which are referred to here as Dharma hall discourses . These short, formal talks were given traditionally in the Dharma hall, with the monks standing, and despite this formal context are highly revealing of Dōgen's humor and personality. In addition, volume 8 of Eihei kōroku includes 20 somewhat longer shōsan , or informal talks, all given at Eiheiji after 1245; and 14 hōgo , or Dharma words, most based on letters to students, some identified, all from before Dōgen moved away from the capital city of Kyoto in 1243 to the remote mountains in the northern province of Echizen. Volume 8 also includes a 1242 revised version of Dōgen's renowned early essay Fukanzazengi , a version of which is also sometimes included in editions of Shōbōgenzō . Volume 9 of Eihei kōroku is a collection of 90 kōan cases selected by Dōgen with his own verse comments, and volume 10 is a collection of Dōgen's Chinese poetry dating back from his four years of study in China, beginning in 1223, through his last years of teaching at Eiheiji before his death in 1253.

Except for the first volume of Eihei kōroku , from talks prior to his departure from Kyoto in 1243, the Dharma hall discourses in Eihei kōroku are the primary source for Dōgen's teaching at Eiheiji. These jōdō talks seem to be the genre of teaching he preferred at Eiheiji after he had finished writing the vast majority of the longer essays included in Shōbōgenzō , although he apparently continued editing some of those and also penned some new essays. The Eihei kōroku Dharma

-122-

hall discourses are presented almost exclusively in chronological order, compiled by three of his leading disciples, including Senne, the author of the main commentary on the 75-fascicle edition of the Shōbōgenzō; his primary successor Ejō; and Gien, who later was abbot of Eiheiji. Although often based on Chinese Chan sources, Dōgen's talks to his cadre of disciples at Eiheiji show the development of his later teaching and reveal his own style of presentation.

Following Dōgen's death, the seven major disciples present at Eiheiji, together with their disciples over the next several generations, managed to spread the Sōtō lineage and teaching widely in the Japanese countryside. Thus, Sōtō became one of the most prominent schools of Japanese Buddhism (second only to the Pure Land Jōdō Shinshū in number of parishioners). As just one notable example of the spread, Dōgen's immediate disciple Kangan Gi'in returned home to the southern island of Kyushu, where he initiated a Sōtō lineage that persisted to modern times. 1

Although not my main focus, it is worth mentioning that one major aspect of Dōgen's career is his comprehensive introduction of the Chan gong'an (Jp. kōan) literature to Japan. His writings reveal an extraordinary mastery of a wide breadth of this material. In the Shōbōgenzō essays, he comments on kōans in an original manner, with panoramic elaboration on particular stories in what has been called the “scenic route.” 2 In Eihei kōroku , on the other hand, we can see Dōgen experimenting freely with variations on different traditional genres of kōan commentary from the jōdō in the Chinese Chan recorded sayings literature.

A comprehensive analysis of Dōgen's training methods as portrayed in the whole Eihei kōroku is far beyond the scope of this chapter, but I will consider several of the Dharma hall discourses that reveal key aspects of Dōgen's approach. In particular, I will focus on a detailed reading of one talk from 1248, which provides insight into how Dōgen saw major aspects of his own evolving teaching methods and their intended effects on his students. The selection of other Dharma hall discourses that I will briefly consider in chronological order express additional significant features of Dōgen's teaching approach. These qualities include his emphasis on practice in everyday activity, the importance of ethical conduct, the bodhisattva context for his teaching, the unified mind developed in zazen, and the importance of the ongoing renewal of practice.

The Courage of Patch-robed Monks.

Dharma hall discourse 239 was delivered at Eiheiji in the late spring of 1247, and presents an insight into a primary context of Dōgen's training intention:

Entering the water without avoiding deep-sea dragons is the courage of a

fisherman. Traveling the earth without avoiding tigers is the courage of a

-123-

hunter. Facing the drawn sword before you, and seeing death as just like

life, is the courage of a general. What is the courage of patch-robed monks?

After a pause Dōgen said: Spread out your bedding and sleep; set out

your bowls and eat rice; exhale through your nostrils; radiate light from

your eyes. Do you know there is something that goes beyond? With vitality,

eat lots of rice and then use the toilet. Transcend your personal prediction

of future buddhahood from Gautama. 3

This talk exemplifies Dōgen's emphasis on practice in ordinary everyday activity, including even using the toilet. We can also note his whimsical humor in comparing the courage of monks to that of fishermen, hunters, and samurai in combat. In encouraging his disciples, Dōgen cites their daily monastic rituals at Eiheiji, including sleeping in the monks' hall in the same place where they each sit in meditation and formally take their meals. Yet, he adds the intriguing phrase, “radiate light from your eyes,” which is not how we usually conceive of vision as a merely passive perception. However, it is not uncommon to recognize when one is being stared at that looking at someone or something can be an example of the active, even intrusive, potential of vision. Primarily in this text, Dōgen is inspiring his monks to bring dynamic responsibility and attentive caring to all their experience. “Radiating light” implies that vigorous insight and illumination should be applied in each routine activity.

Furthermore, Dōgen here exemplifies his primary teaching of the oneness of practice-awakening, or shushō no itto , For Dōgen, enlightenment is not something to await or hope for in the future, but is implicit and presently available in all daily activity. The last line, “transcend your personal prediction of future buddhahood from Gautama,” references the Buddha's predictions of awakening in the Lotus Sutra , first for his various disciples, but ultimately for all those who find joy in hearing the sutra. Dōgen is telling his disciples to forget aspirations for the future, as they are responsible to fully engage what is in front of them in their everyday lives.

A Mountain Homecoming from Kamakura

Later that year, on the third day of the eighth month of 1247, Dōgen left the remote mountains of Eiheiji and traveled to Kamakura, the capital of the military government established in the late 12th century. Most likely, his main patron, Hatano Yoshishige, arranged the visit, presumably to promote Dōgen's teaching. We do not know what actually happened there, except from what Dōgen said when he returned to Eiheiji after more than seven months. His Dharma hall discourse 251 was given on the 14th day of the third month of 1248, the day he returned:

-124-

On the third day of the eighth month of last year, this mountain monk

departed from this mountain and went to the Kamakura District of Sag-

ami Prefecture to expound the Dharma for patrons and lay students. On

this month of this year, just last night, I came home to this temple, and

this morning I have ascended this seat. Some people may have some ques-

tions about this affair. After traversing many mountains and rivers, I did

expound the Dharma for the sake of lay students, which may sound like I

value worldly people and take lightly monks. Moreover, some may ask

whether I presented some Dharma that I never before expounded, and

that they have not heard. However, there was no Dharma at all that I have

never previously expounded, or that you have not heard. I merely explained

to them that people who practice virtue improve; that those who produce

unwholesomeness degenerate; that they should practice the cause and ex-

perience the results; and should throw away the tile and only take up the

jewel. Because of these, this single matter is what this old man Eihei has

been able to clarify, express, trust, and practice. Does the great assembly

want to understand this truth?

After a pause, Dōgen said: I cannot stand that my tongue has no means

to express the cause and the result. How many mistakes I have made in my

effort to cultivate the way. Today, how pitiful it is that I have become a

water buffalo. This is the phrase for expounding Dharma. How shall I

utter a phrase for returning home to the mountains? This mountain monk

has been gone for more than half a year. I was like a solitary wheel placed

in vast space. Today, I have returned to the mountains, and the clouds are

feeling joyful. My great love for the mountains has magnified since before. 5

William Bodiford interprets this talk as reflecting the Eiheiji monks' strong disapproval of Dōgen's trip to Kamakura. 6 Some of the monks at least had “some question about this affair,” and thought that Dōgen might “value worldly people and take lightly monks.” Dōgen indeed seems defensive, claiming he had not taught anything in Kamakura that he had not also taught his monks at Eiheiji. In several of his Shōbōgenzō essays in the early years after leaving Kyoto, while establishing Eiheiji, Dōgen had tried to encourage his monks in their challenging, austere temple site by talking about the importance of monastic practice, as opposed to that of lay practitioners, for transmitting the Dharma. Although he did have lay students attend his talks at Eiheiji, his travels to teach powerful donors at the capital in Kamakura for so long might have felt like a betrayal to some his monks, who remained committed to the rigorous life at Eiheiji.

In late 1246, in Dharma hall discourse 200, Dōgen had apologized, “I'm sorry that the master [Dōgen] does not readily attend to others by disposition.” 7 He acknowledges, “This temple in the remote mountains and deep valleys is not easy

-125-

to reach, and people arrive only after sailing over oceans and climbing mountains.” Yet he encourages his monks that, based on their commitment of the “Mind of the Way,” or bodhicitta , the mountains are highly conducive to spiritual development.

Returning to his homecoming to Eiheiji from Kamakura, recorded in Dharma hall discourse 251, in regard to the teaching of karma and its ethical implications stressed therein, to practice virtue and not unwholesomeness is an emphasis found in much of Dōgen's later teaching. This increased accent is perhaps the greatest, or perhaps even the only, major shift in Dōgen's later teaching, as reflected in his shifting views of the celebrated fox kōan about not ignoring cause and effect. This issue has been discussed comprehensively in Steven Heine's book, Shifting Shape, Shaping Text: Philosophy and Folklore in the Fox Kōan? The spread of Sōtō Zen in the medieval period by Dōgen's successors was helped by the performance of large lay ordination bodhisattva precept ceremonies, which had been initiated by Dōgen and provided the populace with both ethical guidance and a spiritual connection to the Zen lineage. 9 Significantly, Dōgen, upon his return to Eiheiji from Kamakura, proclaims the centrality of these ethical concerns for both monks and laypeople.

Demonstrations of Practice Clarified in the Dawn Wind

Later in 1248, a few months after returning from Kamakura, in Dharma hall discourse 266, Dōgen presents a brilliant description of his training program with a five-part typology of zazen practice in relation to his style of teaching. This incisive talk reveals a remarkable awareness by Dōgen of his pedagogical methods. I will suggest interpretations of these modes of teaching and their implications for understanding Dōgen's overall approach to practice:

Sometimes I, Eihei, enter the ultimate state and offer profound discussion,

simply wishing for you all to be steadily intimate in your mind field. Some-

times, within the gates and gardens of the monastery, I offer my own style

of practical instruction, simply wishing you all to disport and play freely

with spiritual penetration. Sometimes I spring quickly leaving no trace,

simply wishing you all to drop off body and mind. Sometimes I enter the

samadhi of self-fulfillment, simply wishing you all to trust what your

hands can hold.

Suppose someone suddenly came forth and asked this mountain

monk, “What would go beyond these [kinds of teaching]?”

I would simply say to him: Scrubbed clean by the dawn wind, the

night mist clears. Dimly seen, the blue mountains form a single line. 10

-126-

Dōgen describes four teaching modes and their intended impact on his students, with his capping verse indicating a fifth mode. These are not presented as a sequential training program or as stages of progression or development. In many places in his writings, including in Eihei kōroku , Dōgen clearly affirms the strong repudiation within the Caodong tradition of practice that involves any system of stages and instead declares that practice is based on immediate awareness and active engagement. As just one example, in Dharma hall discourse 3oi from 1248, Dōgen says, “Not accompanied by the ten thousand things, what stages could there be?” 11

These four, or perhaps five, characteristics of his teaching approach appear to be useful in varied circumstances as appropriate to the teaching issue at hand. They are explicitly related to varied realms of practice, including practice amid everyday activities, but also all might pertain to the activity of zazen, or sitting meditation, which Dōgen had at times described as the samadhi of self-fulfillment or as dropping body and mind that is mentioned in two of the first four characteristics. But all five modes may readily be seen as meditation instructions, as well as directions for mindful, constructive awareness during all of his disciples' conduct.

Dōgen's first line, “Sometimes I enter the ultimate state and offer profound discussion, simply wishing for you all to be steadily intimate in your mind field,” reveals a major aspect of the zazen practice he promotes. This “ultimate state” is a rendering of ri (Ch. li), literally “principle” or “truth,” commonly used in Chinese Buddhist discourse to denote awareness of the ultimate or universal aspect of reality as opposed to particular aspects of conventional, phenomenal reality. Dōgen's desired effect involves practitioners developing steadiness and intimacy with their field of mind. In his celebrated essay “Genjōkōan,” Dōgen says, “To study the Buddha Way is to study the self.” 12 Key to Dōgen's zazen praxis is just settling, not getting rid of thoughts and feelings, but finding some space of steadiness in oneself. Intimacy develops with the whole field of awareness, which includes everything, including all sense objects, even as new thoughts arise.

Dōgen says he wishes all beings, and especially his audience of disciples, to be intimate in their own mind field. This intimacy includes becoming familiar and friendly with habits of thinking, the particular modes of constructing this mind field that is thought of as “mine.” Beneath the constructed identity lies the realm of awareness that Dōgen recommends to practitioners as a vital aspect of zazen— becoming familiar with habits of thinking, grasping, desire, and aversion, and resulting patterns of reaction, but also awareness of the underlying deep interconnectedness of mind and environment.

Dōgen says that the teaching he does to encourage this intimacy for his students is that he himself enters the ultimate state and offers profound discussion. He sees his own deep settling in connection with ultimate universal awareness and openness as encouraging his students to settle. Developing this steadiness

-127-

includes gratitude and appreciation for the mind field of awareness, which has its own shifting patterns.

For his second training mode, Dōgen says, “Sometimes, within the gates and gardens of the monastery, I offer my own style of practical instruction, simply wishing you all to disport and play freely with spiritual penetration.” Such practical instruction, “within the gates and gardens of the monastery,” refers to Dōgen's various instructions for monastic procedures. Such material can be found in various places in Shōbōgenzō , as well as in Eihei kōroku , but most of this material, Dōgen's major writings about standards for the Zen monastic community written in Chinese, is collected in Eihei shingi , which was collected several centuries after Dōgen. 13 The many Zen monastic forms may function as a latticework for ethical conduct, with rules upheld and consequences enforced, and might be seen as rigid proscriptions or restrictive, hierarchical regulations. For example, Eihei shingi includes a short essay with 62 items on the proper etiquette to be taken when interacting with monastic seniors. Although Dōgen does offer in Eihei shingi detailed procedural instructions, often borrowed from the Vinaya or previous monastic regulations, his clear emphasis is attitudinal instruction and the psychology of spiritually beneficial community interaction. Zen monastic regulations for Dōgen function as helpful guidelines to support awareness.

In “Chiji shingi,” the final essay, which takes up nearly half of the full text of Eihei shingi , it is remarkable how many of Dōgen's exemplary figures from Chan lore (as contained in ten of the 20 stories cited) are involved in rule-breaking or at least rule-bending, sometimes even resulting in temporary expulsion from the monastery. 15 Monastic regulations and precepts are clearly at the service of Dōgen's priorities of total dedication to the spiritual investigation of reality and of commitment to caring for the practice community's well-being.

What Dōgen says he is encouraging with his practical instruction is not merely following rules, but “simply wishing you to sport and play freely with spiritual penetration.” Spiritual penetration or insight requires paying close attention. These instructions concern the sangha, or the community of practitioners, and also support individual zazen, with forms for moving around the meditation hall, for sitting, and for performing ceremonies. But Dōgen says that the point is to play freely. Even for zazen, or sitting while facing the wall and assuming an upright posture and mudra, Dōgen's practical instructions are aimed at supporting the playfulness of his practitioners. He is encouraging his students to play freely both mentally in zazen, as well as in engagement with everyday life, while supporting detailed attention, caring, and spiritual penetration.

For the third aspect of his teaching, Dōgen says, “Sometimes I spring quickly leaving no trace, simply wishing you all to drop off body and mind.” This phrase, dropping off body and mind, or shinjin datsuraku , is another synonym Dōgen often uses for zazen, but also to express total enlightenment. Such dropping of

-128-

mind and body is not equal to discarding intelligence, or self-mutilation, or suicide. This dropping body and mind is just letting go. In his “Song of the Grass Hut Hermitage,” an eighth-century teacher honored by Dōgen, Shitou (Jp. Sekitō) says, “Let go of hundreds of years and relax completely.” 16 This is another way to say drop off body and mind. This is fully accomplished by totally letting go, and it does not indicate not paying attention or failing to take care of body and mind. Dōgen's sometimes abrupt exclamations or enactments recorded in Eihei kōroku , such as throwing down his fly-whisk or just stepping down from his teaching seat to end the talk, are demonstrations of his “springing quickly” to spark such immediate release.

The fourth kind of teaching Dōgen offers is a little more intricate. He says, “Sometimes I enter the samadhi of self-fulfillment, simply wishing you all to trust what your hands can hold.” This samadhi of self-fulfillment is a technical term, yet another of Dōgen's names for zazen. This practice is discussed in one of his earliest essays, Bendōwa . 7 This samadhi of self-fulfillment, self-enjoyment, or self-realization, jijūyū zanmai , is another way in which Dōgen elaborates the meaning of zazen in his teaching approach. Dōgen designates this samadhi of self-fulfillment as the criterion for zazen. 18 He wishes his students to enjoy, realize, and fulfill their constructed self, connected beyond limited self-identity to the totality of self, and thereby sometimes called nonself.

The three Chinese characters for self-fulfillment are pronounced in SinoJapanese as ji-jū-yū. Ji means self, and jūyū as a compound means enjoyment or fulfillment, but jū and yū read separately mean literally to accept one's function. These two characters might be interpreted as taking on one's place or role in life. Dōgen indicates in this phrase that when the practitioner accepts his life, his potential and qualities, and enjoys these, that he thereby discovers self-realization and fulfillment. This is not mere passive acceptance, but actively taking on and finding one's own way of responding, feeling, and accepting the current situation with its difficulties and richness.

Dōgen says he enters the samadhi of self-fulfillment so his followers can “trust what your hands can hold.” Part of zazen is simply learning to actually take hold of who one is and the tools available, and to trust that. Trust might be rendered as faith, or simply as confidence. Dōgen wants his students to trust their own qualities and ability to engage practice. The image of what is held in the hands is reminiscent of the implements held in the many hands of Kanzeon, or Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva of compassion, and evokes the practice of skillful means or using whatever is handy to help relieve suffering and awaken beings. Dōgen's samadhi of self-fulfillment as he describes it here can thus be seen as intending to provoke faith and skillful means in his students.

Dōgen has quite impressively provided four primary aspects of practice and of his teaching strategy or pedagogy. Their aims might serve as a typology of

-129-

practice: to be steadily intimate in one's mind field, to disport and play freely with spiritual awareness, to drop off body and mind, and then to trust what one's hands can hold. These modes are inherent aspects of zazen practice. I know of no other Zen writing that has described zazen directly in this manner, but these are all aspects of the practitioner's intimate awareness of breath and of her own upright posture, also applicable in engagement in everyday activity.

It is noteworthy that each of these four modes is introduced with a term translated in this context as “sometimes.” The word Dōgen uses here for “sometimes” is uji , which also the title of a highly celebrated essay from Shōbōgenzō that has often been translated as “Being Time.” 19 In this essay, Dōgen presents a teaching about the multidimensional flowing of time as existence itself, which has been analyzed by modern commentators, including those in the Kyoto School of Japanese philosophy, as a unique philosophy of temporality. For Dōgen, Zen practice engages the present particular temporal situation of causes and conditions, not some abstracted eternal present. Dōgen sees the temporal condition as moving in many directions that are not reducible to linear clock-time, although that also is being time. Time does not exist as some external, objective container, but time is exactly the current dynamic activity and awareness. The four aspects of zazen and teaching described in this 1248 Dharma hall discourse need not be seen in terms of Dōgen's teaching about being time as presented in the Shōbōgenzō essay from 124o. However, the overtones of his using this term cannot be ignored. Thus, we might also see these four practices as four aspects of the function and attentive practice of being time, or uji .

Concluding this Dharma hall discourse, Dōgen offers a fifth response, not introduced with the term “sometimes,” and which might be seen as going beyond any particular being time while still invoking the specific occasion of dawn. Together, these five approaches might perhaps be correlated to the Sōtō Zen teaching of the five ranks or degrees. The five-ranks teaching first attributed to Dongshan Liangjie (Jp. Tōzan Ryōkai), founder of the Chinese Caodong (Sōtō) school, was initially expressed in his “Song of the Precious Mirror Samadhi.” These are five interrelationships between the real and apparent aspects of life and practice. The two sides can also be rendered as the ultimate and phenomenal, or universal and particular, respectively. Their five interactions have been designated in various ways, with one version being the apparent within the real, the real within the apparent, coming from within the real, going within both apparent and real, and arriving within both together. 20 The first, the particular within the universal, might be seen in the students' intimacy with their mind field from witnessing Dōgen expressing the ultimate state. The second, the universal within the particular, may be seen in the students' realizing spiritual penetration from following monastic procedures. The third, coming from within the universal, might be represented by Dōgen “springing quickly,” prompting immediate dropping of

-130-

body-mind. The fourth, going within both particular and universal, may be exemplified by trusting what is handy while in the samadhi of self-fulfillment. And the fifth, arriving together within both particular and universal, might be recognized in the foreground and background of the blue mountains forming a single line, as discussed next. However, as appealing as such an interpretation might be, the five modes of practice described by Dōgen in this 1248 Dharma hall discourse should not be reduced to a mere expression of that five-ranks system, as they are much richer than this or any other formulation or system.

After presenting the first four aspects Dōgen adds, “Suppose someone suddenly came forth and asked this mountain monk, ‘What would go beyond these kinds of teaching?'” Dōgen often uses the phrase “Buddha going beyond Buddha” to indicate the practice of ongoing awareness or awakening. This dynamic process is not something to be calculated or grasped, but is an organic engagement of going beyond. However well or poorly practitioners may feel they are playing freely with spiritual awareness, an endless unfolding of all of these approaches is possible. Having presented a vision of the fourfold heart of zazen, Dōgen is ever ready to further develop his awakening.

Dōgen imagines one of his students coming forward and asking, what would go beyond those teachings? He responds with a poetic capping verse to his four approaches, “Scrubbed clean by the dawn wind, the night mist clears. Dimly seen, the blue mountains form a single line.” Saying “scrubbed clean by the dawn wind,” Dōgen is concerned not simply with one time of day, but with the sense of freshness available in any inhale or exhale. “Scrubbed clean by the dawn wind, the night mist clears” speaks to the process of bringing oneself back to attention and awareness, waking up and realizing the immediate presence of body and mind. He encourages experiencing this every morning and realizing that this occurs breath after breath as well. “The night mist clears,” sometimes hanging around for a while and sometimes suddenly dissipating. Either way one might feel “scrubbed clean by the dawn wind.” Wind also serves as a customary Zen metaphor for the teaching and the flavor of awareness.

Dōgen adds, “Dimly seen, the blue mountains form a single line.” This evokes the concrete image of distant mountains. The intervening space between and around mountains, as seen for example in the empty space of Japanese ink-brush landscape paintings, is significant here, evoking the spaciousness of awareness accessible in zazen. But since teachers are known by their mountain names, this image may also refer to the lineage formed by the Zen teachers who kept the practice alive before Dōgen. He might as well have said, “Dimly seen, the Zen monks form a single line,” as in a row of meditators in the monks' hall, or on begging rounds. This concerns each mountain, each molehill, each situation, each problem, each master, each practitioner, or each aspect of the mind field, seen dimly, as they all form a single horizon. It might

-131-

be envisioned as just this oneness, the single horizontal line for the kanji one, or the single line seen as a circle. This describes wholeness or totality. All diverse aspects of practice, of life, of the difficulties of the world, or of perplexity at how to respond may be forming a single circle or a single line in Dōgen's poetic capping verse. Such a sense of wholeness is the fifth aspect of zazen, including all the others in some way.

The single line acts as a metaphor for interconnectedness. But why does Dōgen say “dimly” of the insight into interconnectedness? The “dimly” here suggests the oscillation between seeing each particular mountain and then seeing the single line. They are foreground and background, both in the same image. Sitting zazen formally, facing the wall, one keeps eyes open with a soft gaze, and one can be open to what is in front and around, just as with ears open. Thus, one might see only dimly, balancing between the sharpness of one's particular life and the more amorphous background wholeness.

This briefbut illuminating Dharma hall discourse can be seen as an amazingly concise account of Dōgen's training program related to zazen, everyday practice, and his conveying of the Dharma. He reveals a lucid awareness not only of his own teaching modes, but of the results he seeks to inculcate in his disciples from employing each of these approaches.

The Moon Shining on All Beings and Oneself

A later brief Dharma hall discourse, number 434, from spring 1251, provides a reminder of the significant bodhisattva background for Dōgen's teaching:

The family style of all buddhas and ancestors is to first arouse the vow to

save all living beings by removing suffering and providing joy. Only this

family style is inexhaustibly bright and clear. In the lofty mountains, we

see the moon for a long time. As clouds clear, we first recognize the sky.

Cast loose down the precipice, [the moonlight] shares itself within the ten

thousand forms. Even when climbing up the bird's path, taking good care

of yourself is spiritual power. 21

Dōgen evokes the bodhisattvic background of his teaching. The first priority is to “arouse the vow to save all living beings by removing suffering and providing joy.” This Mahayana context and “family style” is sometimes easy to ignore in Zen studies amid all of the colorful kōan discourse and its dharma combat rhetoric. In a later Dharma hall discourse, number 483 from early 1252, the last year for which there are recorded jōdō before Dōgen's final illness, Dōgen tells his monks that true homeleavers must “carry out their own family property to benefit and relieve all the abandoned and destitute.” 22 His emphasis on relieving suffering is clearly not trivial.

-132-

Returning to Dharma hall discourse 434, after reminding of their bodhisattva mission, Dōgen provides important instructions and a praxis paradigm for his monks by first saying, “In the lofty mountains, we see the moon for a long time. As clouds clear, we first recognize the sky.” This poetically evokes that the purpose of their monastic training in the mountains of Eiheiji is to spend a long time immersed in meditatively communing with and examining the wholeness of the moon and finally recognizing the spaciousness, a synonym for the sky, of unconditioned awareness. But such well-honed realization is not sufficient. After such training, monks must depart their monastic enclosure, “cast loose down the precipice,” and share this with all beings, the 10,000 forms. The image he cites for awakened practice, “the bird's path,” is an image used in varied modes by the Caodong founder Dongshan, so Dōgen here invokes the style of his practice lineage. Dōgen closes with a friendly reminder to his monks to “take good care of yourself,” which is a necessary element for the use of spiritual power.

The Endless Shoots of Zazen

Dōgen's final 165 Dharma hall discourses delivered during his last three years of teaching, from 125o to 1252, explicitly reference his fundamental praxis of zazen 20 times, while often otherwise addressing zazen indirectly. 23 This demonstrates the continuity of his practice teaching, as his earliest writings also focus on zazen. Much of Dōgen's attitudes to zazen practice are revealed in his brief Dharma hall discourse 449 from late in 1251:

What is called zazen is to sit, cutting through the smoke and clouds with-

out seeking merit. Just become unified, never reaching the end. In drop

ping off body and mind, what are the body and limbs? How can it be

transmitted from within the bones and marrow? Already such, how can

we penetrate it?

Snatching Gautama's hands and legs, one punch knocks over empty

space. Karmic consciousness is boundless, without roots. The grasses

shoot up and bring forth the wind [of the buddha way].

Dōgen's practice of zazen he also sometimes calls “just sitting,” or shikan taza . Here, he describes just sitting as cutting through the confusing smoke and clouds of delusive thinking and attachment. But he emphasizes not seeking merit. This again refers to his value of not seeking some future result or accomplishment from one's practice, that any merit is in the activity and awareness itself and is not to be sought as personal benefit. In this and other talks, Dōgen encourages engagement in the ongoing, endless process of dropping off body and mind by referring to letting go of physical and mental attachments: “Just become unified, never reaching

-133-

the end,” echoes other teachings of Dōgen to fully engage the continuing process of zazen, and his frequently used expression of “going beyond Buddha.” For example, near the beginning of the 1241 Shōbōgenzō essay, “Gyōbutsu igi,” Dōgen says that active or practicing buddhas “fully experience the vital process on the path of going beyond buddha.” 25 Dōgen's training promotes engagement in the active process of zazen and its awareness here and now, rather than some outcome or accomplishment anticipated in the future.

Further, in Dharma hall discourse 449, Dōgen says, “Already such, how can we penetrate it?” Frequently, in both Shōbōgenzō and Eihei kōroku , he urges his students to further penetrate or study his teachings or phrases from traditional kōans. Here, he says his audience is “already such,” referring to the fundamental principle of Buddha-nature and the reality of suchness as already omnipresent, not a matter of acquisition, but of the realization of present reality. A little later in 1251, in Dharma hall discourse 474, Dōgen says, “The Buddha nature of time and season, cause and conditions, is perfectly complete in past and future, and in each moment.” 26 Here, and elsewhere in Eihei kōroku , Dōgen refers to the teaching of the underlying reality of Buddha-nature, which he expounded on in “Busshō,” the longest essay in Shōbōgenzō? 2

Continuing in Dharma hall discourse 449, with dharma combat style of rhetoric characteristic of much of the traditional kōan literature and often emulated by Dōgen, he exultantly talks about snatching “Gautama's hands and legs,” and punching out empty space. This might refer to fully realizing emptiness, or sunyata , but also to not being caught in blissful attachment to emptiness. Although karmic consciousness, the conditioned, discursive source of suffering, appears to be boundless, it is also “without roots” and is ultimately an illusion. Thus, Dōgen encourages his disciples to see through the obstacles of attachments that obstruct the dropping of body-mind.

Finally, using the evocative image of grasses shooting up, Dōgen suggests that the vitality emerging in zazen calls forth some appropriate helpful response from the “wind” or teaching of the process of awakening. This is a much later echo of the teaching about self-fulfilling samadhi from his early writing on the meaning of zazen in Bendōwa , in which he describes the mutual response between zazen practitioners and their environment in the following terms: “Because earth, grasses and trees, fences and walls, tiles and pebbles, all things in the dharma realm in ten directions, carry out Buddha work, therefore everyone receives the benefit… and all are imperceptibly helped by the wondrous and incomprehensible influence of Buddha to actualize the enlightenment at hand.” 28 Dōgen is reinforcing for his students that this zazen practice is not a merely personal exercise, but an act involving the dynamic interconnection of all beings.

One of the days in the traditional Chinese monastic calendar that Dōgen observed at Eiheiji was the first day of the ninth month. In Chinese Chan, due to

-134-

the summer heat, the meditation schedule was customarily lessened for the three months prior to that day, at which time the cushions were brought back out and the intensive meditation schedule resumed. At Eiheiji, Dōgen did not in fact decrease the summer zazen schedule but he nevertheless often used that date to give encouragements about zazen. Dōgen's Dharma hall discourse 523 from 1252 is the last such talk given on this occasion, in which he says in part:

Do not seek externally for the lotus that blooms in the last month of the year. Body and mind that is dropped off is steadfast and immovable. Although the sitting cushions are old, they show new impressions. 29

Again, Dōgen emphasizes the necessity for endless, ongoing practice. Further engagement in zazen leads to more insight, with new impressions in the mind, as well as increased physical pressure from sitting on the cushions.

Conclusion

The Dharma hall discourses of Eihei kōroku reveal how Dōgen trained his monks in his final decade of teaching at Eiheiji, including how he understood the function of this training. Apparent are aspects of Dōgen's personality, his sense of his own limitations, his humor and warmth, and his deep commitment to teaching. My analysis offers just a slight peek into the richness of the source materials. But this selection of Dharma hall discourses demonstrates Dōgen's emphasis on practice in everyday activity; the essential role of precepts and ethical conduct; the importance of bodhisattva intention and practices; the sense of wholeness available in zazen; and a focus on sustainable, continuous practice. Furthermore, a profound five-part pedagogy of Zen training is depicted in the Dharma hall discourse 266 from 1248.

-135-

Notes

DZZ Dōgen zenji zenshū, ed. Kagamashima Genryū, et. al., (Tokyo: Shunjūsha, 1988–1993).

T Taishō shinshū daizōkyō (Tokyo Daizōkyōkai, 1924–1935).

ZZ Zoku zōkyō (Kyoto: Zōkyō shoin, 1905–1912).

1. For Dōgen's seven major disciples, see Taigen Dan Leighton and Shohaku Okumura, trans., Dōgen's Extensive Record: A Translation of the Eihei Kōroku (Boston: Wisdom Publications, 2004), pp. 19–25.

2. See Steven Heine, Dōgen and the Kōan Tradition: A Tale of Two Shōbōgenzō Texts (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1994).

3. Leighton and Okumura, Dōgen's Extensive Record . pp. 238–239 Kosaka Kiyū and Suzuki Kakuzen, eds. Dōgen zenji zenshū , vol. 3 (Tokyo: Shunjūsha, 1989), p. 160.

4. Gene Reeves, The Lotus Sutra (Boston: Wisdom Publications, 2008), p. 225.

5. Leighton and Okumura, Dōgen's Extensive Record , p. 246; Kosaka and Suzuki, eds. Dōgen zenji zenshū , vol. 3, pp. 166–169.

6. William Bodiford, Sōtō Zen in Medieval Japan (Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 1993), pp. 30–31.

7. Leighton and Okumura, Dōgen's Extensive Record , p. 215; Kosaka and Suzuki, eds., Dōgen zenji zenshū , vol. 3, pp. 136.

8. Steven Heine, Shifting Shape, Shaping Text: Philosophy and Folklore in the Fox Kōan (Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 1999).

9. Bodiŕbrd, Sōtō Zen in Medieval Japan , pp. 118, 163.

10. Leighton and Okumura, Dōgen's Extensive Record , pp. 257–258; Kosaka and Suzuki, eds., Dōgen zenji zenshū , vol. 3, pp. 178.

11. Leighton and Okumura, Dōgen's Extensive Record , p. 281; Kosaka and Suzuki, eds. Dōgen zenji zenshū , vol. 3, pp. 196.

12. Shohaku Okumura, Realizing Genjōkōan: The Key to Dōgen's Shōbōgenzō (Boston: Wisdom Publications, 2010), pp. 2, 75–81.

13. See Taigen Dan Leighton and Shohaku Okumura, trans., Dōgen's Pure Standards for the Zen Community: A Translation of Eihei Shingi (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996).

14. Leighton and Okumura, trans., Dōgen's Pure Standards , pp. 121–125.

15. Ibid., pp. 127–204.

16. Taigen Dan Leighton with Yi Wu, trans., Cultivating the Empty Field: The Silent Illumination of Zen Master Hongzhi (Boston: Tuttle and Co., 2000), pp. 72–73.

17. See Shohaku Okumura and Taigen Daniel Leighton, trans., The Wholehearted Way: A Translation of Eihei Dogen's “Bendōwa” with Commentary by Kōsho Uchiyama Roshi (Boston: Charles Tuttle and Co., 1997).

18. Okumura and Leighton, trans., The Wholehearted Way , pp. 19, 63–65.

19. For translations of “Uji,” see Kazuaki Tanahashi, ed., Treasury of the True Dharma Eye: Zen Master Dogen's Shobogenzo (Boston: Shambhala, 2010), pp. 104–1ii; Norman Waddell and Masao Abe, trans., The Heart of Dōgen's Shōbōgenzō (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2002), pp. 48–58; Thomas Cleary, trans., Shōbōgenzō: Zen Essays by Dōgen (Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 1986), pp. 102–110; or, with extensive commentary, Steven Heine, Existential and Ontological Dimensions of Time in Heidegger and Dōgen (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1985), pp. 153–162.

20. See Leighton, Cultivating the Empty Field, pp . 8–11, 62, 76–77; Alfonso Verdu, Dialectical Aspects in Buddhist Thought: Studies in Sino-Japanese Mahayana Idealism (Lawrence: Center for East Asian Studies, University of Kansas, 1974); and William Powell, trans., The Record of Tung-shan (Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 1986), pp. 61–65.

21. Leighton and Okumura, Dōgen's Extensive Record , p.390; Kosaka and Suzuki, eds., Dōgen zenji zenshū , vol. 4, pp. 24.

22. Leighton and Okumura, Dōgen's Extensive Record, p. 430; Kosaka and Suzuki, eds., Dōgen zenji zenshū , vol. 4, pp. 64.

23. The number 165 for jōdō from 1250 through 1252 begins with those from Buddha's parinirvana day, the 15th day of the second month of 1250. Six more were undated after Buddha's Enlightenment day in 1249, the eighth day of the 12th month, and some of these were likely in what we now call 1250.

24. Leighton and Okumura, Dōgen's Extensive Record , p. 404; Kosaka and Suzuki, eds., Dōgen Zenji Zenshū , vol. 4, pp. 38.

25. Tanahashi, Treasury of the True Dharma Eye , p. 260.

26. Leighton and Okumura, Dōgen's Extensive Record , p. 423; Kosaka and Suzuki, eds., Dōgen Zenji Zenshū , vol. 4, pp. 58.

27. Waddell and Abe, The Heart of Dōgen's Shōbōgenzō , pp. 59–98.

28. Okumura and Leighton, trans., The Wholehearted Way , p. 22.

29. Leighton and Okumura, Dōgen's Extensive Record , p.466; Kosaka and Suzuki, eds., Dōgen zenji zenshū , vol. 4, p. 102.