ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

池辺元子 Ikebe Motoko (1900-1990)

Motoko Ikebe

by Arthur Braverman

Buddhism Now, May 2002

http://buddhismnow.com/2013/08/31/motoko-ikebe-by-arthur-braverman/

Do you call a female Zen teacher a Zen master or a Zen mistress? In Japan, this isn’t a problem, at least, not in ‘orthodox’ Zen institutions. There are abbesses of Zen nunneries, but they don’t really get to be considered Zen teachers in the formal sense. Women with spiritual power in Japan can become mediums, astrologers and spiritual advisors, but not, as far as I know, Zen masters.

This doesn’t mean that you can’t find female Zen teachers in Japan outside of the ‘orthodox’ Zen circles. When Japanese people feel some kind of spiritual prowess in a person, they don’t care whether it is a he or a she; they will turn to that person for advice.

Historically, the Japanese have considered women to be the proper interpreters of the teaching of the gods. In fact, the first spiritual and political leader of Japan on record was Himiko (or Pimiko), a queen whose authority was based on her religious or magical powers. She was a Shaman who the Chinese chronicles describe as unmarried with a thousand women attendants and one man, and who spent her time with magic and sorcery. She was a mediator between the people and their gods.

The Meiji constitution (1889) asserted that the emperor was the successor in an unbroken, sacred blood lineage, based on male descendants. But the people aren’t as simple-minded as their leaders or their institutions. When someone demonstrates the power of presence, they go to that person for advice regardless of gender.

So when Motoko Ikebe (1900-1990) demonstrated a special awareness or perhaps a lifestyle indicative of someone out of the ordinary, people came to her for advice. Motoko sensei, however, was different from the typical woman seer with magical powers, though she may have been just that for many who came to her for advice. Motoko recommended zazen and practised it regularly herself.

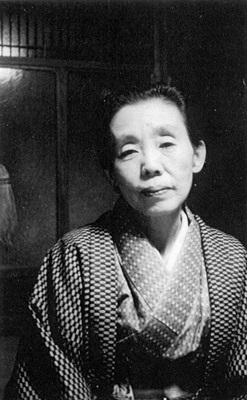

Photograph of Motoko Ikebe courtesy of Arthur BravermanIn 1940, she and her husband, Kohaku, moved to Nose, a small mountain village in the hills of Hyogo Prefecture. Both artists with ideas about the oneness of art, nature and spirituality, they moved into the country to live simple lives, getting their spiritual and physical sustenance from the land. Kohaku, Motoko’s senior by ten years, was her mentor as well as her husband. When he started practising zazen, Motoko followed. Zazen became a major part of their lives.

When Kohaku was dying at age seventy-one, he told Motoko that he no longer worried about her. He realised that she had become her own person, and he could leave her knowing that she was free of needing him. Motoku was to live another thirty years after Kohaku’s death and was to become an inspiration to many. With the publication of a small book about her life in 1967 at the request of Nakayama Shinsaku, President of the Shunjusha publishing house, Motoko Ikebe became known to the Japanese world outside of her small circle of friends.

A group of students joined her for Zen meetings in which they listened to her talks and sat zazen together. Though Motoko has been dead since 1990, her students still get together for zazen meetings and listen to tapes of her Zen talks. The following are excerpts from some of those talks.(1)

There is no expression with deeper meaning than that of the word ‘just’ in ‘just sitting.’ No matter what, throwing away the activity born of ignorant doings, you sit there; which means you are not being fooled. You stop delusion and sit.

‘But most people can’t do that,’ you say. That’s because they hold onto delusion. ‘Delusions rise again. There’s nothing I can do.’ You shake your head and shake off deluded thought, thinking ‘Now it’s okay.’ Then, ‘They rise again.’ For an hour you keep shaking your head, but there’s nothing you can do. Grasping delusions and trying to push them away, you think they will disappear. Just stop that, stop deluded thinking. Because you give these delusions your attention, they keep coming back.

Just cease deluded thinking and sit. The highest work a human being can do is to cease deluded thinking. Zazen means just sitting. Don’t be deluded. Don’t think ‘good’ don’t think ‘bad’. It is said, ‘Clarify life, clarify death, that is the most important meaning of Buddhism.’ Truly, just sit . . . That’s all there is.

[From Bi wo Jôjû Suru Mono: Ikiru Shisei wo Motomete, pp.122-124]

. . . We’ve fallen into this existence because of our disregard for cause and effect, so we have to return to a place where we stop the causal mind.(2) We have to transcend cause and effect. That is zazen. Zazen is ceasing to create karma. That’s the reason we sit, isn’t it? To stop creating karma and only that. Human beings can do nothing other than that. It’s a lowly existence. We still think things like, ‘I’m a little more intelligent, or I’m a little luckier . . . ’ But those thoughts amount to nothing. ‘I’m a little healthier,’ and so on, none of that will do us any good, it’s of no use whatsoever. Just sit. To actually travel the road of truth you only have to stop creating delusion. That’s the only thing humans can do. Since it was humans who created delusions, all they have to do is stop. That’s the only reason for sitting. Never mind what will happen next. This wholeness will act on us from within. Humans should do what they can. That is, cease creating delusion. Then awakening is already there, for anyone and everyone, without a doubt. It’s written in the Shushôji (Dôgen’s Practice Enlightenment chapter of the Shôbôgenzô) and in many other places. So there is no need to worry, just cease creating delusions. ‘Ah, there it is again!’ That thought too is delusion. If you give it attention, there is no limit to delusion. So quit creating delusions and just sit. Then when you face this way, which is your life, based on your practice, the posture in which you stop creating delusions is the sole true mind. Life’s true wisdom is derived from this, from this work. It will arise from the true mind, undoubtedly.

When you say, ‘Another delusion! I can’t do anything about it.’ You are giving these delusions wheels, aren’t you? And when you say, ‘Why do they manifest? I’m so pitiful.’ You are holding onto this ‘pitiful self’. There is no such thing.(3) So just let go and there will be no problem. ‘If that’s true,’ you say, ‘if it’s okay to just sit there in a fog, wouldn’t it be better to just go to sleep?’ Waking up and sleeping are relative. If you’re not sleeping, you are awake. We are not talking about problems of this world like waking or sleeping.

There is something unrelated to all that—something that continues to be awake through eternity, something that continues though you die. That’s where you have to sit. There, your mind becomes perfectly clear and warm. You may think I mean warm in the sense of body temperature, but I don’t. You may think that by perfectly clear I mean like the blue sky or a moonlit night. But examples like those are unnecessary. This transcends examples. The saint, Ippen, called it, ‘quiescent no-mind’. You must sit within ‘quiescent no-mind’. The mind is not put to work. When it arises, you leave it as is. You let it be. It’s because you pay attention to it that things arise one after the other ceaselessly. We call this [ceaseless arising] the demon because it stands in the way of our escaping from the three worlds.(4)

Now if you truly sit in quiescent no-mind, it’s quite difficult to do it for an hour straight. You may say, ‘I hear sounds.’ Since that is proof that your ears are working well, rejoice in it. If you can’t hear anything when you are sitting, that would be reason for alarm. You may say, ‘My feet are becoming numb.’ If your legs don’t become numb, something may really be wrong. Don’t concern yourself with numbness; it can’t be helped. Simply switch the position of your feet.

Just cease creating delusion; don’t delude yourself. You have to sit in a manner in which delusion has no real relation to you. That’s the way to sit . . .

. . . When you were born, when you die, and between that, every breath is life-death. So you need not worry about it; there is no death. If you do zazen, you will realise this fact.

[From The Attitude of the Way Seeker, taken from Nyôze, a newsletter published by Mizuno, one of Ikebe’s disciples. This was from issue 27, published on 27 March 1994.]

NOTES1) The excerpts are taken from Living and Dying in Zazen, the story of five Zen teachers and a Zen community, by Arthur Braverman.

2) I have tentatively translated inshin as causal mind. This lecture is transcribed from a tape, so not knowing the characters, I am not sure of its literal meaning.

3) No pitiful self, no self, period.

4) The world of desire, the world of form, and the world of no-form—the worlds of unenlightened beings.

PDF: Living and Dying in Zazen: Five Zen Masters of Modern Japan

by Arthur Braverman

Weatherhill, 2003, 176 p.

[A marvelous book combining the life stories and teachings of five masters - Kodo Sawaki, Sodo Yokoyama, Kozan Kato, Motoko Ikebe, and Kosho Uchiyama.]