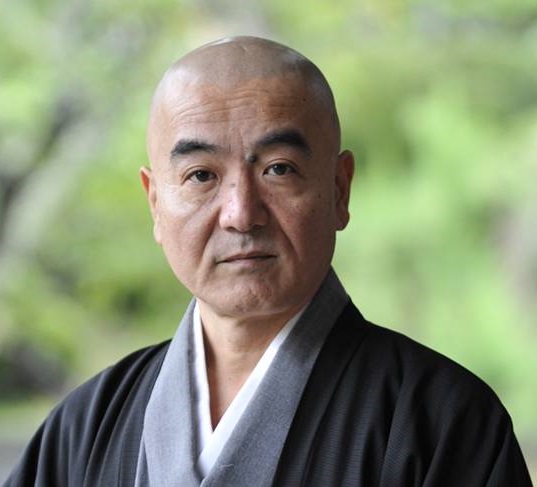

玄侑宗久 Genyū Sōkyū (1956-)

Né dans la préfecture de Fukushima en 1956, Genyû Sôkyû est sous-directeur du temple Fukujuji de la secte zen Rinzai-Myôshinji. En 2001, il a reçu le prix Akutagawa (le Goncourt japonais) pour Chûin no hana , « Au-delà des terres infinies». Il a également publié de nombreux essais sur le bouddhisme et des entretiens avec des personnalités scientifiques, qui ont remporté un très grand succès. En 2007, ses échanges avec la célèbre biologiste Yanagisawa Keiko, « Le sûtra du Cœur, discussion sur la vie », ont obtenu le prix des Lecteurs de la revue Bungei Shunju.

Liste des œuvres traduites en français

• 2001 : Au-delà des terres infinies (中陰の花), roman traduit par Corinne Quentin, Editions Philippe Picquier, 2008; Picquier poche, 2010.

• 2003 : Vers la lumière (アミターバ 無量光明), roman traduit par Corinne Quentin, Editions Philippe Picquier, 2010; Picquier poche, 2013.

• 2005 : Langueur (つ れづれ), dans Meet n°11 (Tokyo/Luanda, p. 39-43), texte traduit par Corinne Quentin, Editions Meet, Octobre 2007.

• 2012 : Il n'y a rien à dire, mais c'est ici que le chemin commence, suivi de Je traîne ton ombre, dans L'Archipel des séismes - Écrits du Japon après le 11 mars 2011, sous la direction de Corinne Quentin et Cécile Sakai, Editions Philippe Picquier, 2012.

• 2013 : La Montagne radieuse (光の山), récits traduits par Corinne Quentin et Anne Bayard-Sakai, Editions Philippe Picquier, 2015; Picquier poche, 2017.

Au-delà des terres infinies

Ecrite par un moine zen, voici l'histoire d'un petit temple niché au milieu des montagnes, de Sokudô, le jeune bonze qui en a la charge, de sa femme Keiko et des événements qui vont venir perturber une routine paisible et bien installée. Mme Ume, une médium douée du pouvoir de " communiquer avec le divin ", vient de prédire sa propre mort et sa disparition annoncée s'accompagne de signes et de manifestations inhabituels. Mais peut-être ne s'agit-il que d'illusions ? Au fur et à mesure que ces signes, d'une touche légère, pénètrent peu à peu le réel, le lecteur se sent emmené dans un voyage à travers les mystères de la vie et de la mort. Dans le quotidien de ce temple et des fidèles qui le fréquentent, la banale réalité côtoie de près l'inexplicable, avec une sereine simplicité. Et voilà que ce petit livre, tel un kôan zen, vient bousculer nos certitudes et ouvrir notre esprit à des questions dont chacun doit trouver la réponse en lui-même.

Vers la lumière

Au soir de sa vie, une femme, originaire d'Osaka, rejoint sa fille mariée à un bonze dans un petit temple bouddhiste. Peu après, elle apprend qu'elle est atteinte d'un cancer incurable. Entourée de la sollicitude des siens, elle accepte sereinement la mort qui approche et décrit avec curiosité et humour ce qu'elle ressent : les transformations physiques, les sensations inconnues, l'activité des médecins et infirmières autour d'elle... Puis, peu à peu, elle perd la notion du temps, souvenirs et rêves viennent se mêler aux événements du présent, et elle avance vers une autre dimension. S'inspirant de son expérience personnelle de moine zen ayant beaucoup lu ce que les religions disent de l'au-delà et les scientifiques des mystères de la physique, l'auteur aborde l'expérience de la mort et ce qui la suit, avec audace et quiétude. Le chemin qu'il décrit est un chemin vers la connaissance et la lumière.

La Montagne radieuse

Les récits du moine zen Genyû Sôkyû sont de fines descriptions des errements de l'âme humaine face à un danger imprévisible, inconcevable, lorsque hommes et femmes tentent, avec les moyens dont ils disposent, de revivre, de retrouver la lumière. Lui dont le temple est proche de la centrale de Fukushima, il a partagé le quotidien des habitants touchés par le tsunami et l'accident nucléaire de mars?2011. Les leçons d'espoir, d'amour et de courage qu'il retrace résonnent en chacun de nous. « Écrites comme des flashs éblouissants, ces histoires frappent par leur force méditative ». (Marine Landrot, Télérama).

![]()

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/S%C5%8Dky%C5%AB_Gen%E2%80%99y%C5%AB

PDF: Das Fest des Abraxas

by Gen'yū Sōkyū

Aus dem Japanischen übersetzt und mit einem Nachwort versehen von Lisette Gebhardt

Berlin, 2007.

![]()

Gen'yū Sōkyū is a novelist and essayist, as well as the 35th chief priest of the Fukuju-ji Zen Buddhist temple of the Rinzai sect in the town of Miharu, Fukushima. Born and raised in Miharu, he started writing novels while reading Chinese literature and drama at Keio University, Tokyo. His second novel, Chūin no hana (Flowers in Limbo), was awarded the prestigious Akutagawa Prize in 2001. His work, which explores the application of Buddhist or Zen teachings in everyday contexts, has been translated into French, German, Korean and Chinese.

Fukushima, where he still lives, suffered heavy blows from the March 2011 earthquake and tsunami and the ensuing nuclear power plant disaster. Genyū is a member of the Reconstruction Design Council in Response to the Great East Japan Earthquake, an advisory body to the prime minister, and is actively engaged in presenting his views to domestic and global audiences. In 2014 he was awarded the MEXT Award for the Arts for his collection of stories about the triple disaster, Hikari no yama (Mountain Glow).

His website can be found here.

AWARDS

2001 Akutagawa Prize, for Chūin no Hana (Flowers in Limbo)

2007 Bungei Shunju Readers' Prize, for Hannya Shingyo: Inochi no Taiwa (The Heart Sutra: Dialogue of Life)

Abraxas Festival

(Aburakusasu no matsuri / アブラクサスの祭)This is an engrossing story that realistically depicts a Buddhist monk's struggles with depression.

In Japanese fiction, Buddhist monks are often portrayed as emerging triumphant over spiritual turmoil, but that is not the case in this story. Though a monk, the protagonist is unable to overcome his spiritual suffering and finds relief only in medicinal drugs. His struggles are described from the viewpoint of the protagonist himself, his wife, his temple's chief priest (Genshu), and the chief priest's wife.

The protagonist, Jonen, is a monk at a Zen temple in a small town in northern Japan. He suffers from both manic-depression and schizophrenia, and he relies on medicine to maintain a semblance of balance. As a student at a university in Tokyo, his overriding interests were rock music and sex. But when symptoms of mental illness appeared, his parents committed him to a mental institution in his hometown of Kagoshima, where he eventually lost interest in such things. Upon being released from this institution, he followed his parents' advice and entered a Buddhist temple. After a period of training, he left the temple and began attending a university in Kyoto. Eventually he quit the university without graduating and returned to Kagoshima. There he found a job, but it did not last long. Following the chief priest's advice, Jonen stopped taking his medicine. Unfortunately, this resulted in his being tormented by hallucinations and delusions, and he attempted to drown himself. He left the temple, and after returning to Kyoto for some time, entered another temple in Kanagawa Prefecture. There he met his future wife, Tae, and with her he returned to the temple in northern Japan, where he is when the novel begins.

Jonen's father, who has been sending him the medicine, suddenly passes away, and Jonen becomes increasingly unstable. It is then that Jonen proposes that, as a means of finding himself, he hold a live concert in town. Tae and Genshu help him make preparations, but just before the concert begins, signs of schizophrenia reappear. On stage Jonen experiences a sense of exaltation he has never felt before, but gradually his behavior turns erratic. In the eyes of Tae, however, Jonen has taken a turn for the better.

Flowers in Limbo

(Chuin no hana / 中陰の花)Chuin (roughly translated here as "limbo") is a Buddhist term referring to the 49 days after a person's death, during which the soul has yet to depart for its next existence?in short, the threshold between this life and the next. This story depicts the events taking place from the death of Ume?a shamaness who foresaw the future and accurately predicted events including the day of her own death?to the ceremony that marks the 49th day after her passing, as seen through the eyes of Sokudo, a Zen priest.

Six years earlier, Sokudo had married a woman named Keiko, bringing her to the temple to live with him. Two years later Keiko suffered a miscarriage. The modern-minded Sokudo prides himself on his "practical" nature, using a computer to manage records of the temple's visitors and searching the Internet for information. Yet while displaying this hunger for scientific and technical knowledge on the one hand, he also accepts and shows interest in the new-age religion that one of his temple's followers begins to dabble in. When his wife confronts him with questions like "What happens to people when they die?" and "Will Ume be able to become a Buddha in her next life?" he shares words from Buddhist teachings with her, but refrains from making statements of any certainty.

Following Ume's death, Sokudo discovers in talking with his wife that she has been preoccupied more than he knew with thoughts of their lost baby, and that she had been going to see Ume. He hangs a tapestry his wife has woven from twisted strands of paper in the main hall of his temple, and together the couple hold a ceremony to pray for the ascent of Ume and their lost child to Buddhahood. In this collection, the title story is printed alongside Asagao no oto (Sound of the Morning Glories), a short story about a woman, raped twice and pregnant against her will, who visits a female magician to pray for the repose of the aborted child.

Mountain Glow

(Hikari no yama / 光の山)Published roughly two years after the March 2011 earthquake-tsunami-nuclear disaster that rocked Japan's Tohoku region, this noteworthy collection compiles stories that could only have been written by a man of religion who was also a victim of the disaster himself. The author is head priest of a Buddhist temple in Miharu-machi, just 45 kilometers west of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant that suffered multiple meltdowns.

The six stories, which are all set in the Tohoku area, depict with deep sympathy the daily struggles of survivors as they pick up the pieces and try to resume their lives.

The title story is told largely in flashback from 30 years after the disaster. The narrator's father, a lifelong farmer, takes up an odd sort of volunteer work following the disaster. He prunes other people's trees and shrubs upon request, and hauls the trimmed foliage and branches back to his own property. He pulls their weeds and takes those home as well. He also accepts contaminated soil, trees and plants, and other waste brought to him by others, piling it all up on his substantial spread. Three years later, the mound of debris has reached a height of 20 meters. Worried about the dangers of radiation, the narrator visits with dosimeter in hand and sharply questions his father, who only says that it's fine, he's just helping out all the people who have no place to put their waste. Twenty-five years later his father dies from complications following a cold at the age of 95. In accordance with his wishes, his body is cremated atop the now 30-meter high mound. The mound begins to smolder from the fire, giving off a fluorescent, pale purple light, and by three days later the entire mountain is emitting a faint glow.

In Kōrogi (Cricket), an elderly Buddhist monk witnesses and attends to so many deaths that he begins to lose his mental faculties. In Kotarō no gifun (Kotarō's Indignation), the young wife of a firefighter who got caught in the tsunami agonizes over whether she wants her missing husband's body to be found, or fears it will be found?thus putting an end to the last, faint wisp of hope to which she clings. Amenbo (Water Strider) tells of a mother who leaves her husband and moves away from Fukushima in order to protect her small child from the effects of radiation, and of her childhood friend who remains behind. Unfolding with compelling realism, the stories cannot be read without summoning tears.

Mountain of Light by Gen'yū Sōkyū – excerpt

Translated from Japanese by Sim Yee ChiangAkutagawa Prize winner Gen'yū Sōkyū has an unusual vocation among litterateurs: he is the chief priest of a temple in Fukushima , where nuclear disaster struck following the earthquake and tsunami of March 2011. Both a leader and a major voice in reconstruction efforts, Gen'yū uses fiction to grapple with the catastrophe, and in this story, Mountain of Light, he imagines (perhaps even hopes for) a future of provincial ascendance and “Irradiation Tours”. In this excerpt, the narrator relates his coming to terms with his father's devotion in collecting the community's “irradiated” — their radiation-contaminated waste, in other words.

—The editors at Asymptote, 27 Dec 2016

The next time I saw Dad was at Mom's funeral. He himself would die three years later at ninety-five—twenty-five years after our last conversation—of old age, not cancer. After my mother's cremation, he spoke to me.

“Your ma had a hard time of it, but it was all worthwhile. Thanks to the irradiated, we managed to live meaningfully, right up to the end, and that's no joke. When my time comes... you'll burn me on top of that mountain, right?”

His hearing wasn't so good by that time, so while I said “Don't be stupid,” apparently what he heard was “Okay, I'll do it,” although I didn't realise this until much later. He held my hands in front of Mom's altar and said “Thank you” over and over again... It might've been a misunderstanding, but that was the first time he had ever shown me gratitude.

My brother and sister-in-law had only offered incense at the crematorium, and were no longer there. He was a consultant to an electronics manufacturer, and even though he said he had a meeting to attend, I was sure they had left out of fear. I too had debates with the missus about the effects of low-level exposure, almost every night. Eventually we stopped speaking, and came to see each other as “contaminated.” We'd separated by then. And that's when I finally realised that we were both being completely ridiculous.

I'm sure all of you will agree—I mean, think about it, academics had all these opposing theories and no one was willing to budge. Some people said that anything up to one hundred thousand times the intensity of background radiation is fine, look at astronauts, they're fine—and then others demanded that we spend trillions of yen on decontamination to scrape off fertile soil with low-level radiation. The Hormesis and Prophylaxis camps, yeah, that's what they were called. Both sides wanted the other to calm down and talk things through, but like me and the ex, they just couldn't do it. You could say my divorce was the result of a proxy war, haha.

People—organisations are even worse—go to terrifying lengths to save face. The ICRP, that's the International Commission on Radiological Protection, they of all people should've created spaces for discussion, but showed no intention of doing so. And then public opinion was set on throwing every last baby out with the bathwater: if nuclear reactors were bad, then all radiation was bad too. In short, no one was calm.

But as you know, after the power plant accident, it was the ICRP who recommended raising the radiation exposure limit by twenty to a hundred times of the normal value. After that was rejected, they just stayed silent, same as me and the ex. Even now I have no idea who's right. But what's certain is that the radioactive potassium and carbon and whatnot in our bodies emit a fair amount of radiation, with or without the reactors. Somebody weighing sixty kilos would put out, oh, five thousand becquerels or so. Anyway, the Commission never officially changed their stance on low-level exposure after that. And now we have all of you taking part in this Irradiation Tour, coming to see the mountain my old man made. Radon hot springs are popular once more, and Fukushima's population is even growing rapidly.

What was I... oh, right—that was quite a ramble—I was telling you about Dad's request.

For the record, it wasn't cancer. He might've said “Cancer wouldn't be bad,” but in the end he had a prolonged bout of the autumn flu and kicked the bucket, just like that.

I got the news from my cousin, and when I came back Dad was already laid out in the main room, around there. Yes, right there, where the blond man is sitting, haha. I lifted the white cloth, and saw my old man looking solemn for the first time. It was as if he'd taken off the okame mask—I had never seen that face before, honest.

I spent the whole night thinking. I recalled what Dad said at Mom's funeral, and I wasn't sure what to do about his cremation. But the answer soon came to me. You see, my mother's remains had disappeared from the altar.

Since Mom died eight years ago, I'd started coming back home a little more often. I'd retired from my job, and I didn't have a family of my own. I wasn't that worried about Dad living alone, rather I'd come to believe his mountain may have been some kind of miracle.

On one of those visits, he'd told me about their dog's death, and how he had buried it atop that mountain. Sitting by my old man's pillow, I looked over at the altar and noticed that while my mother's picture was there, her remains were not. I put the pieces together and went outside. It was a still, humid night at the beginning of summer.

The sound of insects filled the air. It was my first time ever on that mountain. I realised, halfway up, that it had become much taller than before. It was even taller than it is now, nearly thirty metres, I'd wager. As I went up the winding path, I was aware of the dosimeter packed in my bag, but you know, I didn't take any measurements. I think my feet were a bit shaky, but I wasn't scared of anything anymore. Dad did the same thing every day, and he lived peacefully until the age of ninety-five, just like Mom.

Now and then, I felt his presence. Staring at the ground as I climbed, in the dim light of the moon, it seemed my old man was saying “It's okay, it's okay” and smiling overhead.

As I expected, there were two pieces of natural stone at the top, set about one metre apart. At some point, Dad had made and maintained a grave for Mom and another for their dog up there. And that's why this mountain is like one of those burial mounds.

Looking around, I saw the neon signs of the neighbouring town twinkling like countless stars. Of course, the stars in the sky were also countless, and so beautiful. Perhaps Dad built the mountain with the knowledge of this view. I was suddenly reminded of him saying the word “meaningfully” at Mom's funeral. The last words I'd heard Mom say also seemed to echo in my ear: “Someone come by?”

Thinking back later, the mountain seemed to be glowing faintly that time too, but I couldn't distinguish it from the silvery moonlight.

I went to the temple the next morning and asked the priest to carry out the funeral at my home. I had the newspapers run not just a death notice, but a full obituary too. My old man had single-handedly taken on the irradiated of this town as well as other parts of the prefecture, so I felt the public ought to know about his death. I might've been a little carried away.

The funeral was an incredible affair.

I was very grateful for the hundred-odd wreaths, and the not one but five priests, but this wasn't your regular congregation—this was a mob. The prefectural governor came, five or six mayors came too. Pretty sure there were over two thousand attendees. But the real highlight came during the cremation, after everyone had gone home.

The priest from my family temple was actually very supportive. When I told him about my old man's request, he said “Let's do it. We'll perform the cremation on top of that mountain.” After the ceremony, the guys from the neighbours' association carried Dad's coffin up the mountain. As our ancestors did, we gathered kindling, placed a board on the kindling, and laid the coffin on the board. Straw from nearby rice fields, once considered hazardous, was piled up high on the coffin. It was starting to get dark, and the fire burned beautifully, it did. By that time, the Hormesis school of thought was already pretty mainstream, so I wasn't surprised by the hundred or so people who had stayed behind to watch from the foot of the mountain. What I didn't expect was what happened after those people had left. I'd invited the priest into the house, and as we were drinking, I heard a massive bang. I went outside to take a look, and the whole mountain was smouldering, not just the area around my old man's body.

“It's okay.”

That wasn't my old man, it was the priest standing next to me.

After all, the mountain was made up of countless trees, branches, grass, all perfectly flammable. The priest probably also knew that the temperature would go up to five, six hundred degrees at most, and as long as it didn't go over seven hundred degrees the caesium wouldn't disperse.

“Is that true?”

“Yes, it's okay, it's okay, all of it will stay in the ashes.”

The priest came across as a salesman—no, I hear he used to work at an incinerator, maybe that was it—he spoke with complete assurance. I have no idea which of them first came up with the “it's okay” mantra. Anyway, we made a makeshift table and continued drinking outside, sitting on upturned beer crates.

That's when we finally saw it. Where the sky was turning into night, the air had a kind of sheen, it seemed to be lit from some deeper layer. It was the mountain, giving off a pale purple fluorescence. Now and then flames peeked out, smoke billowed up, but the purple aura that encompassed the whole shone with a light that would repel darkness forever. It was as if the cloud bearing the noble Amitābha had descended before our eyes.

The mountain continued to smoulder for several days, gradually shrinking and becoming more compact. And every night, the whole mountain would emit a soft light. No one knows why. All sorts of experts came and investigated the thing, but it's still a mystery. After the usual forty-nine days of mourning, Dad's bones were buried close to Mom's gravestone, and since then the light seems to have become stronger, haha, but that's probably my eyes playing tricks on me.

Look, there it is, you'll start to see it as night falls. On your feet, everyone, and let's ascend the Mountain of Light.

It's okay, no need to rush. Radiation's not as strong as it was five years ago, but there's still plenty to soak up.

Sorry, one more thing—I said earlier that this mountain's also a burial mound, so first, I'd like all of you to put your hands together in prayer for a moment.

Thank you.

Okay then, please put on your shoes and head outside. Now, now, no pushing. I know you can't wait to get all the exposure you can, but as in all things, sharing is caring. More and more foreigners visiting these days, but I still don't have any materials in English, sorry about that. PU-RI-I-ZU KA-MU A-GE-I-N, haha.

Ah, just look at that. You wouldn't think such beauty could come from this world. Translucent, pure, noble, and absolutely toxic. If it were the colour of lapis lazuli, I guess it'd herald the coming of Bhaiṣajyaguru the Medicine Buddha instead of Amitābha. Wow, even the souvenir store's neon sign is reflected in the sky—we're looking at the Pure Land of the East here, everyone.

All right, everyone. Please follow me, single file. The staff will give you detailed instructions, please do as they say. It's okay, it's okay. Everyone gets the same exposure. Yes, this is the eighty millisievert course. Hey, you there, no sneaking off to get two rounds in, that's a violation. Good grief, you guys... Those of you who haven't changed into your white robes, it's okay, take your time. Right, we're heading out now, nice and easy... rokkonshōjō, the sky is clear, rokkonshōjō the mountain shines...