ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

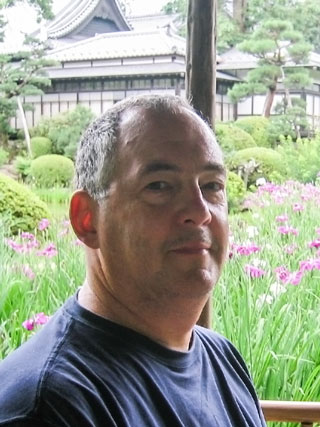

T. Griffith Foulk

T. Griffith Foulk is professor of Asian religions at Sarah Lawrence College and co-editor-in-chief of the Soto Zen Text Project based in Tokyo. In his youth he trained for several years at Zen monasteries in Japan, where he still maintains close ties. He received a PhD in Buddhist Studies from the University of Michigan in 1987, and has taught at the University of Michigan, the University of Toronto, and UC Berkeley. He has received Fulbright, Mellon, Japan Foundation, and National Endowment for the Humanities fellowships, and has twice been elected to the Steering Committee of the Buddhism Section of the American Academy of Religion. His publications include Standard Observances of the Soto Zen School (Vol. 1: Translation, and Vol. 2: Introduction, Glossaries, and Index), and numerous monographs on the intellectual and institutional history of Zen Buddhism in China and Japan.

T. Griffith Foulk (B.A., Williams College, 1971; Ph.D., University of Michigan, 1987) holds the Riggs Chair in Religious Studies at Sarah Lawrence College, where he has taught Buddhism and other Asian religions for more than 20 years. He previously headed the graduate program in East Asian Buddhism at Michigan, and has been a visiting professor at Toronto, UC Berkeley, and Stanford. Recognized around the world as a leading authority on the history of Chinese Chan and Japanese Zen Buddhism, Foulk has authored many scholarly monographs on textual, ritual, and institutional aspects of those traditions. Since 1996, he has been co-editor-in-chief of the Sōtō Zen Text Project, a major translation project sponsored by the Administrative Headquarters of Sōtō Zen Buddhism in Tokyo. From 1973 through 1976, Foulk practiced as a resident lay practitioner at the Kaisei-ji Sōdō training monastery in Nishinomiya, Japan. There he engaged in kōan practice under Zen master Kasumi Bunshō (1905-1998), and began a life-long friendship with Takahashi Yūhō, who at the time was a leader of the monks in training. In 1983, Foulk was formally ordained as a monk in the Sōtō school of Zen and trained briefly at its headquarters monastery, Eihei-ji.

http://zeninink.com/about/

Standard Observances of the Soto Zen School

Vol. 1: Translation, and Vol. 2: Introduction, Glossaries, and Index

by T. Griffith Foulk

History of the Soto Zen School

by T. Griffith Foulk

PDF: The "Ch'an School" and Its Place in the Buddhist Monastic Tradition

Dissertation, The University of Michigan, 1987

PDF: The Ch'an Tsung in Medieval China: School, Lineage or What?

by T. Griffith Foulk

Pacific World Journal, New Series Number 8, Fall 1992, pp. 18-31.

PDF: Chanyuan qinggui and Other “Rules of Purity” in Chinese Buddhism

by T. Griffith Foulk

The Chanyuan qinggui and other “Rules of Purity” in Chinese Buddhism by T. Griffith Foulk covers a range of materials in the genre of rules for Ch'an monasteries, which were adaptations of classic Indian Vinaya monastic rules. The Chanyuan qinggui was published in 1103 and was the culmination of a variety of previously published monastic rules. Legend has it that Baizhang Dazhi (720-814) (WG: Pai-chang Huai-hai; J: Hyakujo Ekai) is credited with creating the first Ch'an monastic rules but Foulk suggests otherwise. Although Baizhang is revered in Ch'an monastic circles almost as much as the Buddha, Foulk argues that the Ch'an monastic rules are “the common heritage of the Chinese Buddhist tradition during Song and Yuan” (p 307) rather than the exclusive domain of the Ch'an school.

PDF: “Rules of Purity” in Japanese Zen

by T. Griffith Foulk

In: Zen Classics: Formative Texts in the History of Zen Buddhism (2006 ), Chapter 5

PDF: The Form and Function of Koan Literature: A Historical Overview

by T. Griffith Foulk

In: The Koan: Texts and Contexts in Zen Buddhism (New York, 2000), Chapter 1

PDF: The Spread of Chan (Zen) Buddhism

by T. Griffith Foulk

In: The Spread of Buddhism. Edited by Ann Heirman and Stephan Peter Bumbacher. Brill, 2007, pp. 433-456.

PDF: Daily Life in the Assembly

by T Griffith Foulk

in: Buddhism in Practice, Buddhism in practice, edited by Donald S. Lopez, Jr. - Abridged ed. pp. 339-356. Princeton Readings in Religions. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995, 2007.

("The Daily Life in the Assembly (Ju-chung jih-yung) and Its Place Among Ch'an and Zen Monastic Rules". Ten Directions 12.1(1991): 25-34.)

The second oldest set of Chan monastic rules that survives today is the Daily

Life in the Assembly (Ruzhong riyong), also known as the Chan Master Wuliang

Shou's Short Rules of Purity for Daily Life in the Assembly (Wuliang shou chanshi

riyong qinggui). The text was written in 1209 by Wuliang Zongshou 無量宗壽, who

at the time held the office of chief seat in a Chan monastery.

Foulk, Theodore Griffith and Robert H. Sharf

"On the Ritual Use of Ch'an Portraiture". Cahiers d'Extrême-Asie 7 (1993): 149-220.

Republished in Chan Buddhism in Ritual Context, edited by Bernard Faure (London, New York: RoutledgeCurzon, 2003), pp. 74-150.

Foulk, Theodore Griffith

"Ineffable Words, Unmentionable Deeds". Monumenta Nipponica 47,4 (1992): 521-526.

Book review of > PDF: The Rhetoric of Immediacy: A Cultural Critique of Chan/Zen Buddhism by Bernard Faure

Foulk, Theodore Griffith

"Myth, Ritual and Monastic Practice in Sung Ch'an Buddhism".

In: Patricia B. Ebrey and Peter N. Gregory, eds Religion and Society in T'ang and Sung China. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1993. 147ff

Foulk, Theodore Griffith

"The Zen Institution in Modern Japan".

In: Kenneth Kraft, ed. Zen: Tradition and Transition: A Sourcebook by Contemporary Zen Masters and Scholars. New York: Grove Press, 1988.

Foulk, Theodore Griffith

"The Sinification of Buddhist Monasticism". University of Pennsylvania 44th Annual South Asia Seminar Conference Annals.

Foulk, Theodore Griffith

"Ch'an Monastic Practice, 700-1300".

Foulk, Theodore Griffith

"Issues in the Field of Asian Buddhist Studies: An Extended Review of 'Sudden and Gradual: Approaches to Enlightenment in Chinese Thought'". Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies.

Foulk, Theodore Griffith

"Japanese Views of Zen Institutions in Sung China". In: Welter, Albert F., and John McRae, eds. Creating the World of Zen: The Transmission of Sung Dynasty Ch'an Buddhism Throughout East Asia.

Foulk, Theodore Griffith

"Zen Buddhist Ceremony and Ritual".

On Zen Arts and Culture

by T. Griffith Foulk

What is Zen?

Zen is a school of Buddhism that evolved in medieval China and subsequently spread to the rest of East Asia: Korea, Vietnam, and Japan. It was born of cross-cultural interaction, as alien Buddhist monastic institutions and philosophical principles imported from India were modified to conform with indigenous Chinese cultural values and practices, most notably those associated with the Confucian and Daoist traditions.

Zen teachings derive largely from the Indian Mahāyāna Buddhist doctrine of “emptiness” (Sanskrit, śūnyatā), which holds that all names and conceptual categories, while useful for navigating and making sense of our world, ultimately fail to provide a complete and accurate picture of what really exists. Language is a powerful tool that we humans cannot dispense with, but at root it is simply a set of conventional designations that we use to communicate with one another and to collect and transmit an ever-inceasing body of knowledge down through the generations. Unfortunately, we misuse that tool, for we lose sight of it even as we employ it. We come to believe that the real world, in itself, is actually comprised of the quasi-static, separate but interacting “things” that we have distinguished and named for our own practical purposes. That is a kind of delusion that inevitably leads to anxiety, disappointment and suffering, for reality is always more complex and changeable than our conceptual models of it.

Zen Buddhism teaches that if one makes an intense and sustained effort at introspection, one can gain a deep intuitive understanding (satori 悟り) of the workings of one's own mind. Such an awakening eases suffering, for it weakens deluded attachment to linguistic constructs by exposing them as products of our own (collective as well as individual) imaginations. Language can now be appreciated for what it is — an infinitely adaptable tool that can be picked up or put down at will — and the “things” and “events” that it conceives are no longer experienced as external chains that bind.

The sayings, calligraphy, and paintings produced in the Zen tradition express the wonder, joy, and awe that one feels in coming “face to face,” as it were, with the real world, as opposed to seeing it only through the veil of conceptual constructs. Awakening to the inherent limitations and pitfalls of language does not mean that one stops speaking, thinking discursively, or writing. On the contrary, it frees one to use words and concepts in a more flexible, creative fashion.

The expression “real world,” of course, is just another verbal construct, a convenient fiction: in the final analysis, there is no such thing that matches our simplistic conception of it. Indeed, Mahāyāna Buddhists happily concede that all of their religious teachings, including the key concepts of “delusion” (the condition of ordinary living beings) and “awakening” (becoming a buddha), are but conventional designations that are, from the ultimate point of view, false. To employ even the language of Buddhism itself is thus to risk deluded attachment, but if used with skill and compassion such linguistic formulations can help lead others to liberation.

Meditation (dhyāna in Sanskrit, channa 禪那 or chan 禪 in Chinese, sǒn 禪 in Korean, thiến 禪 in Vietnamese, zen 禪 in Japanese), is a basic Buddhist practice that found its way from India to China and the rest of East Asia. Seated meditation (Ch. zuochan 坐禪, J. zazen) has always been embraced by the Zen tradition as a powerful means of temporarily shutting down discursive thinking, or detaching from it even as it runs its habitual course, and thereby pointing the way to escape from the self-made prison of language.

In its rhetorical style, Zen Buddhism is very Chinese. Unlike Chinese translations of Indian Buddhist scriptures, which tend to be long-winded philosophical discourses that rely on allegory and syllogism, Chinese Zen texts employ a terse, colloquial, down-to-earth and sometimes enigmatic metaphorical language that is reminiscent of the Daoist classics. Doctrinally, however, Zen sayings remain true to the Indian Mahāyāna Buddhist teaching of “emptiness,” for they point to the limitations of language and conceptual thought itself while enjoining us to wake up to the real world of immediate experience that we actually live in, “before,” “apart from,” and “in the midst of” the linguistic processing in which we habitually engage.

Zen Calligraphy and Ink Painting

In its modes of artistic expression, Zen Buddhism has its roots in the literati culture of imperial China. The styles of calligraphy and ink painting that Chinese, Korean and Japanese Zen masters have employed over the centuries originated among the Confucian literati (Ch. ru 儒, J. ju): the socially and economically elite class of scholar-officials in China whose bureaucratic and political careers were launched when they passed a rigorous battery of tests on the Confucian classics. A high degree of education was the mark of the literati class, but they also prided themselves on their skill in using the basic tools and materials of Chinese writing: black ink (Ch. mo 墨, J. boku or sumi), brushes (Ch. bi 筆, J. hitsu or fude) of various sizes amd materials (e.g. bamboo, horsehair), and paper. The writing of orders to underlings and reports to superiors in the imperial bureacracy was the everyday business of scholar-officials, but calligraphy or the “Way of Writing” (Ch. shu dao 書道, J. shodō) was also raised to the level of an art in and of itself, especially when it was employed in the composition of poetic verses, a liesure-time activity that came to have great social significance. In the Confucian traditition, it was believed that the character and intellectual refinement of a “gentleman” (women were largely excluded) were evinced in his calligraphy, which thus came to be called “traces [of the man] left in ink” (Ch. mo ji 墨跡, J. bokuseki).

In addition to developing styles of cursive writing (cao shu 草書, J. sōsho) that were highly artistic and hard for the untrained eye to decipher, some literati used brushes and black ink, in various degrees of dilution with water, to paint scenes from nature — mountainous landscapes, plants, birds, animals, etc. — as well as portraits and caricatures of people. Ink paintings (Ch. mo hui 墨絵 or shui mo hui 水墨絵, J. sumi e or suiboku e) of that sort almost always included calligraphic inscriptions that identified or commented on, typically in verse, the scene or subject portrayed. Such ink painting remained a largely amateur pursuit — an avocation of the literati — in East Asia, whereas formal polychrome painting, which required more specialized techniques and materials, was the domain of a small number of professional artists.

“Amateur” or not, the fact remains that good calligraphy and ink painting both require a high degree of practiced skill and confidence. The medium is such that any undue hesitation or haste with the brush, not to mention any poorly executed or erroneous stroke, results in immediate and irreparable failure. If the brush pauses on the paper, ink pools and spreads uncontrollably. Unintended strokes or splatters cannot be erased, and it is virtually impossible to “paint over” any mistakes. Artists using polychrome oil paints can gradually build up their works, making corrections and alterations as they go. Ink painters and calligraphers have but one shot. Their works — for better or worse — are generally completed in a single, relatively short sitting.

So, how did the Chinese literati arts of calligraphy and ink painting, which originally had no essential connection with Buddhism, find their way to Japan, and how did they become so intimately connected with the Zen Buddhist tradition in that country?

In Song dynasty (960-1278) China, monks who belonged to the Zen school formed a privileged elite that came to dominate the upper echelons of the Buddhist monastic order at large. They succeeded in gaining literati patronage because they were able to make Indian Buddhist teachings appealing to that class of educated scholar-officials. At the same time, they themselves embraced many elements of literati culture, notwithstanding the fact that it was essentially Confucian in its world view and values.

During the Kamakura period (1185-1333) in Japan, a movement arose to import the latest and most prestigious forms of Buddhist teaching and monastic practice that had evolved under the leadership of the Zen school in Song China. The Zen that was initially transmitted to Japan at that time was embraced as a new form of Buddhism, but it employed distinctively Chinese (loosely, “Daoist”) modes of rhetoric and carried with it all the elements of Chinese literati (loosely, “Confucian”) culture. The styles of calligraphy, ink painting, landscape gardening, and tea drinking that were popular in elite circles in China — non-Buddhist as well as Buddhist — all became known as “Zen” in Japan, for the Japanese were initially exposed to them almost exclusively in the setting of the newly established Zen (i.e. Song Chinese style) monasteries.

When Zen monks in medieval China and Japan engaged in calligraphy, they tended to quote sayings attributed to famous ancestral masters in the Zen lineage, or to compose original verses that employed Buddhist tropes and concepts. As in secular literati circles, an eminent monk's “traces left in ink” (Ch. mo ji 墨跡, J. bokuseki). were believed to reflect his character and degree of cultivation. In the Buddhist context, however, it was a monk's level of spiritual attainment, as opposed to mere erudition, that was said to be evinced in his calligraphy.

Ink paintings by Zen monks in China and Japan were stylistically indistinguishable from those of literati artists and featured many of the same natural scenes. Often the only thing identifiably “Zen” about them were the inscriptions, which typically expressed Buddhist sentiments. Only when the subject matter is itself an anecdote or personage from Zen lore can we speak meaningfully of “Zen painting” (Zenga 禅画) as a truly distinctive genre of art. In modern Japan, nevertheless, that term has come to refer in a general way to all works done in the style of Song Chinese literati ink painting, whether or not they were produced by monks, allude to any Buddhist themes in their inscriptions, or depict any people or incidents found in Zen lore.

“Just Sitting”?

DŌGEN'S TAKE ON ZAZEN, SUTRA READING, AND

OTHER CONVENTIONAL BUDDHIST PRACTICES

T. Griffith Foulk

[Chapter 3, in: Dogen: Textual and Historical Studies. Edited by Steven Heine - Editor. Oxford University Press. New York. 2012]

Dōgen has often been cast by modern scholars as the leading proponent of a “pure” form of Zen practice—one in which various conventional Buddhist ceremonies and rituals are eschewed, no “syncretistic” borrowing of elements from the Pure Land or Esoteric Buddhist traditions is tolerated, and no concessions are made to the demands of the laity for funerals, memorials, and offering services for the spirits of their ancestors. The erroneous nature of that depiction, and the notso-hidden agenda of the Japanese scholars who formulated it in the century following the Meiji Restoration, are matters that I have addressed in some detail in previous publications. 1 There is no need in the present chapter to rehash my arguments concerning those matters, but I do wish to revisit what is without question the single most compelling (and, I believe, the only ) piece of concrete historical evidence we have that lends any credence at all to the aforementioned image of the “purist” Dōgen.

The evidence I refer to is the famous, often-quoted passage from Dōgen's Bendōwa , written in Japanese, in which he says: “From the start ( hajimeyori ) of your consultation ( sanken ) with a wise teacher ( chishiki ), have no recourse ( mochiizu ) whatsoever ( sarani ) to burning incense ( shōkō ), prostrations ( raihai ), buddha-mindfulness ( nenbutsu ), repentances ( shusan ), or sutra reading ( kankin ). Just ( tadashi ) sit ( taza ) and attain the sloughing off of mind and body ( shinjin datsuraku suru koto wo eyo).” 2 This passage occurs just after an assertion by Dōgen that all the buddhas and ancestral teachers of the Zen lineage who uphold the buddha-dharma regard sitting upright ( tanza ) in self-enjoyed samādhi (jijuyū zanmai) as the true path that led to their own awakening ( kaigo ), and that sitting upright is the “marvelous means” ( myōjutsu ) employed by all the masters and

-75-

disciples in India and China who attained realization ( satori ). Given that context, the passage in question appears to state quite clearly that sitting upright in selfenjoyed samādhi—the practice of zazen—is crucial to attaining the “sloughing off of mind and body,” which in Dōgen's usage is a synonym for satori or awakening, and that the various other practices named are either unnecessary or perhaps even obstacles to achieving that goal. The passage would thus seem to provide solid evidence in support of those modern spin doctors who have claimed that Dōgen dispensed with all the superstitious beliefs, arcane doctrinal formulations, and religious rituals that other Zen Buddhist monks of his day embraced— including practices such as upholding moral precepts, studying sutras and commentaries, devotional worship, prayer, merit-making, and so on—and that he took instead a “single practice” approach in which he stressed “just sitting” ( shikan taza ) in meditation.

The problem with this interpretation is that it privileges the aforementioned passage from Bendōwa as the essence of Dōgen's teachings and ignores the extensive body of writings in which he not only endorses a wide range of conventional Buddhist practices, but explains in detail exactly how they are to be performed in the daily life of a monastery. In point of fact, all of the particular practices that Dōgen dismisses in that passage—incense burning, prostrations, buddhamindfulness, repentances, and sutra reading—are explicitly and enthusiastically promoted by him in a number of his other works.

In the first half of this chapter, I document that fact in some detail. I then address the question that naturally arises when we consider the passage from Bendōwa within this broader frame of reference: What did Dōgen mean by issuing such apparently contradictory recommendations for Buddhist practice? How can we, as students and interpreters of his teachings, resolve that contradiction? Given the preponderance of historical evidence that points to Dōgen's embrace of all the conventional Buddhist practices he encountered in the large public monasteries of S ong dynasty China, is the passage from Bendōwa something that we should dismiss as an anomaly, an offhand remark that he did not really mean? Could that passage even be an interpolation by later editors of something that Dōgen himself never actually said?

Neither of those explanations are viable, for Dōgen repeated the passage, using nearly identical words, in seven of his other writings: once in the Hōkyōki (Record of the Hōkyō Era), a diary of his personal exchanges with his teacher Rujing at the Tiantong Monastery during the Baoqing (Jp. Hōkyō ) era of the Song dynasty; three times in his Shōbōgenzō (Treasury of the True Dharma Eye); and three times in the Eihei kōroku (Extensive Record of Eihei), a collection of Dōgen's remarks made from the abbot's high seat during convocations in a dharma hall ( jōdō ), his exchanges with disciples, verse comments on kōans, and so on. What is noteworthy about these additional occurrences is that, in six of the

-76-

seven instances, Dōgen explicitly attributed the admonition to “just sit” ( shikan taza ) and “make no use of incense burning… etc.” to his teacher Tiantong Rujing, whom he quoted using classical Chinese. It is virtually certain, therefore, that the passage from Bendōwa is actually Dōgen's translation into Japanese of a saying that originated with Rujing. This complicates the central question I raise in this chapter—what did Dōgen mean by issuing such apparently contradictory recommendations for Buddhist practice?—because we cannot assume that when Dōgen quoted his teacher he was also speaking for himself.

It could be argued that by translating Rujing's dictum and presenting it without attribution as instruction to his students in Bendōwa , Dōgen was not only endorsing it but in effect making it his own. In most of the other instances in which Dōgen cited Rujing's saying, however, he was “raising” ( kyo ) it as a topic to be commented on, not merely offering it as practical advice from an authoritative source. That is to say, he treated Rujing's dictum as an “old case” ( kosoku ) or “precedent” ( kōan): a nugget of wisdom attributed to an old master that is hard to understand on the face of it and therefore demands interpretation. What this means is that Dōgen himself implicitly recognized the tension that existed between his teacher Rujing's admonition to “make no use of incense burning… etc.” and the actual Buddhist practices that were standard procedure in the great public monasteries of Song China, including the Tiantong Monastery where Dōgen trained and Rujing was abbot.

In the second half of this chapter, I cite each of the eight occurrences of Rujing's dictum in its immediate textual context and analyze Dōgen's interpretation of it. In aggregate, the passages in question show that Dōgen himself struggled at first to make sense of the dictum, that he changed his view of it over time, and that what Rujing meant by “just sitting” may have been different from the understanding that Dōgen eventually arrived at.

Conventional Buddhist Practices Embraced by Dōgen

Most of Dōgen's writings on monastic discipline are actually commentaries on the Rules of Purity for Chan Monasteries (Ch. Chanyuan qinggui , Jp. Zennen shingi ) 3 Some modern Japanese scholars have argued that the Rules of Purity for Chan Monasteries represented a form of Chan monastic practice that had already degenerated since the “golden age” of the Tang dynasty, and that Dōgen was a purist who rejected the “syncretic” and “worldly” aspects of Song Chan found in that text, 4 but there is no evidence of that in any of his writings. In virtually every case, Dōgen cites the Rules of Purity for Chan Monasteries as an authoritative work that his disciples should understand and follow to the letter. He disparages unnamed monks in Japan who are ignorant of or refuse to follow that model, and he criticizes individual Chinese monks for various shortcomings, but he never

-77-

voices any disapproval of the forms of Buddhist monastic practice that he encountered in Song China. The particular practices that Dōgen apparently dismissed in Bendōwa are all found throughout the Rules of Purity for Chan Monasteries , and he clearly embraced all of them. Let us consider each of those practices in turn.

Burning Incense

The burning of incense ( shōkō ) in a brazier set on an offering table before an altar on which buddhas, bodhisattvas, devas, ancestors, or other deities are enshrined is a ubiquitous feature of East Asian Buddhist ritual and was already well established as such when Dōgen visited Song China. The burning of fragrant wood may have originated as a substitute for burnt offerings of meat from sacrificial animals, which was practiced both in the brahmanic worship of devas in ancient India and in rites for nourishing ancestral spirits in pre-Buddhist China. In any case, whatever is offered by fire disappears from the human realm, and the smoke apparently conveys it to the heavens, where the devas and spirits reside. In Buddhism, the burning of incense was adopted as a means of worshipping buddhas and other sacred beings that does not involve taking life. Being expensive, however, the burning of incense does involve “sacrifice.” 5 In Buddhist terms, the offering of incense to a buddha, bodhisattva, ancestor, or other spirit enshrined on an altar is conceived as a good deed ( gō ) that produces merit ( kudoku ). Because it counteracts bad odors, incense smoke also came to be understood as a purifying agent. In Buddhist rituals that involve “censing” (kō ni kunjiru ) offerings and official documents in incense smoke, the trope of purification is clearly at play. The burning of incense is also interpreted metaphorically in some Buddhist texts as an analogue for karmic retribution: just as the smell of incense spreads and lingers long after the act of burning it is finished, the performance of good deeds has far-reaching beneficial consequences that “perfume” the world.

In Dōgen's writings on monastic discipline, references to burning incense appear so often that to catalogue all the occurrences here is out of the question. In “Ango,” to cite but one of those writings, the “ceremony of burning incense” ( shōkō gyōji ) as an offering is discussed in at least four different ritual contexts, 6 and it is clear that Dōgen fully endorses the Chinese custom of appointing an incense-burning acolyte ( shōkōjisha ) to serve as one of the five main assistants to the abbot. 7 The recipients of incense offerings mentioned in Dōgen's writings include figures enshrined on altars in a monastery, such as the earth spirit ( dojijin ) and the Sacred Monk (shōsō); 8 the ancestral teachers ( soshi ) of the Zen lineage; Dōgen's own deceased teacher Rujing; a monk's living teacher, when making a formal request of him; the current abbot and other senior officers of a monastery, in the context of thanking them for a kindness shown; the three treasures ( sanbō )

-78-

of buddha, dharma, and sangha; and sutras ( kyō ), monastic robes ( kesa ), and inheritance certificates ( shisho ), which are material objects that represent the Buddha's teachings, the Buddhist sangha, and the Zen lineage, respectively. The practice of burning incense, especially when it takes place before an altar, is often connected with other types of offerings ( kuyō ), mainly those of food, drink, and merit ( kudoku ) that is generated by chanting sutras, dharanis, and buddha names; the merit is dedicated (ekō) to the figure enshrined in conjunction with prayers for various benefits. The practice of burning incense, moreover, is so often conjoined with that of making prostrations that Dōgen seems at times to treat “burning incense and making prostrations” ( shōkō raihai ) as a single unit of ritual behavior. I cite examples of his use of that expression below.

Prostrations

The term that I translate here as “prostrations” ( raihai ) can be rendered more literally as a “bow” or “prostration” (hai) that is rendered as a sign of “respect” or “courtesy” (rai). Standing alone, the word hai has the basic meaning of “to bow,” but its connotations in Chinese and Japanese include “saluting,” “showing deference,” “calling on a superior,” “supplication,” and “worship.” In the East Asian Buddhist tradition, the physical act of making prostrations involves getting down on one's knees and elbows, lowering one's forehead to the floor, and turning one's hands palm up to symbolically take the feet of the Buddha. Quite apart from its Buddhist context, the social meaning of that posture as a sign of submission and humility (if not humiliation) is a human universal, and the making of prostrations has a psychological effect even if the practitioner regards it as a mere formality or “empty ritual.” Buddhist monks traditionally spread a sitting cloth ( zagu ) onto the ground or floor in front of them before making prostrations, to protect their monastic robes (kesa) from being soiled, in both a literal and a figurative sense. In every case, prostrations are made “to” or “before” some person or being, whether in the flesh, in the form of an image (statue or painting), a stupa or mortuary tablet, or just imagined. When there is a physical frame of reference, i.e., when the object of respect (a person or an image) is visible, the prostration generally begins and ends in a standing position facing that object.

In Dōgen's writings, as in the Chinese Buddhist monastic rules he followed, basically two types of prostrations are frequently mentioned: (1) prostrations made to buddhas, bodhisattvas, ancestral teachers, protecting deities, and other figures enshrined on altars or just mentally conjured; and (2) those made by monks to other living monks, either in ritual settings that specify the type and number of prostrations to be made, or spontaneously in connection with individual requests for assistance or benefits and personal expressions of gratitude for things received. Again, there are far too many occurrences of both these types of

-79-

prostration in Dōgen's works on monastic discipline to cite them all here, so I shall just give a few representative examples.

In his “Chiji shingi,” Dōgen stipulates that the monk serving as garden manager ( enju ) should never fail to join the main assembly of monks when they engage in sutra chanting ( fugin ), recitation services ( nenju ), and other major ceremonies. 9 Moreover, “At the vegetable garden, mornings and evenings, he should never neglect to burn incense ( shōkō ), make prostrations ( raihai ), and recite buddha names ( nenju ), dedicating the merit (ekō) [produced by those activities] to the rain god ( ryūten ) and earth spirit ( doji ) 10 Here Dōgen actually enjoins the strict observation of three of the practices that he names as unnecessary in Bendōwa: (1) burning incense as an offering before an altar; (2) making prostrations to a deity as an expression of reverence and/or an act of supplication; and (3) reciting buddha names ( nenju ), which is a form of “buddha-mindfulness” ( nenbutsu ) practice.

In “Ango,” Dōgen discusses the formal salutations ( ninji , literally “human affairs”) that marked the beginning and end of the summer retreat ( ge ango ). The procedure, as he explains it, is as follows:

“Salutations” ( ninji ) are mutual “prostrations” (ai raihai ). For example,

fellows from the same home district, some tens of people, may pick a con-

venient place, such as the illuminated hall ( shōdō ) or a corridor ( rōka ), and

there make prostrations to one another, expressing felicitations on ac-

count of spending the same retreat together.… When dharma relatives

( hakken ) make prostrations to the abbot, this calls for spreading the cloth

twice and making three prostrations ( ryōten sanpai ), or they may just fully

spread the sitting cloth and make three prostrations ( daiten sanpai ).…

Neighbors on the platform ( rintan ) and people in adjacent positions

( rinken ) all get prostrations. Acquaintances ( sōshiki ) and old friends

( dōkyu ) make prostrations together. As for the kind of people who reside

in individual quarters ( tanryō ), including the head seat ( shuso ), secretary

( shoki ), canon prefect ( zōsu ), guest prefect ( shika ), bath manager ( yokusu ),

and the like, one must go to their quarters and make congratulatory

prostrations ( tōryō haiga ). 11As this passage indicates, different relations in the bureaucracy and social hierarchy of a monastery called for different levels of formality in making prostrations. In this chapter, Dōgen mentions a number of forms: “abbreviated three prostrations” ( sokurei sanpai ), “fully spreading the sitting cloth and making three prostrations” ( daiten sanpai ), “spreading the cloth twice and making three prostrations” ( ryōten sanpai ), “nine prostrations” ( kyūhai ), and “twelve prostrations” ( jūnihai ). He also explains the protocol for “prostrations in reply” ( tōhai ), in which senior

-80-

monks politely acknowledge the obeisances paid them by juniors. The formal salutations ( ninji ) that Dōgen describes were also called for in connection with other major events on the monastic calendar, such as the New Year's celebration. In “Jukai,” Dōgen writes:

One must burn incense and make prostrations ( shōkō raihai ) before the

ancestral teachers ( soshi ) and ask [a living teacher] to receive the bodhi-

sattva precepts ( bosatsu kai ). Having received permission, one should

bathe and purify oneself, and don new clean robes. Or, one should thor-

oughly wash one's existing robes, scatter flowers, burn incense, make pros-

trations ( raihai ) and pay homage, and with that body don them. One

should broadly make prostrations to graven images, make prostrations to

the three treasures, and make prostrations to venerable monks of the

abbot class ( sonshuku ), thereby removing all hindrances and purifying

( seijō ) body and mind. 12Here, burning incense and making prostrations are both presented as means of purification. Smoke, of course, can act as a disinfectant and preserving agent; also, incense smoke gets rid of bad smells. Prostrations cleanse one of the pride and arrogance that would hinder reception of precepts. Also, the merit produced by these acts is understood by Dōgen as an agent for counteracting karmic hindrances.

As an example of the somewhat less formal, essentially spontaneous occasions on which prostrations might be made, we have an account of Dōgen's own personal experience, found in “Shisho.” Here, Dōgen reports that when he was in China, he got the chance to see an inheritance certificate that had been written by Chan Master Fozhao ( Busshō zenji ) and was currently in the possession of an abbot named Reverend Wuji ( Musaioshō): “When I first saw it, how great was my feeling of joy! Surely this was thanks to the hidden influence of the buddhas and ancestors. I burned incense and made prostrations ( shōkō raihai ), then unrolled and examined it.” 13 Later, he says, “I went to the abbot's quarters, burned incense and made prostrations, and thanked Reverend Wuji,” 14 for it was Wuji who had allowed him to see a document that was ordinarily kept hidden. The first act of burning incense and making prostrations mentioned here was Dōgen's way of showing reverence for the Chan lineage, as represented in a document that traced Fozhao's line of dharma inheritance back to the Buddha Sakyamuni. It was a mode of ritual so ingrained in the young foreign monk by that time that he seems to have performed it spontaneously. The second was performed as a way of expressing his gratitude to the abbot Wuji. Finally, quite apart from the formal adherence to norms of monastic etiquette, Dōgen argues in “Raihai tokuzui” that making prostrations ( raihai ) to spiritual guides is a practice that helps pave the way to one's own awakening.

-81-

Buddha-Mindfulness

In Japanese Buddhism, the expression “buddha-mindfulness” ( nenbutsu ) most often refers to the practice of invoking the Buddha Amitabha, using the formula “Adorations to Amida Buddha” ( namu Amidabu ), as taught in the Pure Land Jōdo ) and True Pure Land Jōdo shin ) schools that take Hōnen and Shinran as their founders. In the Buddhist monastic institution that Dōgen experienced in Song China and strove to replicate in Kamakura period Japan, however, “buddha-mindfulness” had a broader meaning that included, but was not limited to, the invocation of Amitabha in hopes of gaining rebirth in his pure buddha land, the western paradise. In Song Chinese monasteries, Amitābha was enshrined in the infirmary—a facility called the “life-prolonging hall” ( enjudō ) or, since many monks died there, the “nirvana hall” ( nehandō )—and services for the newly deceased were designed to facilitate their rebirth in his pure land. In addition, as a matter of routine religious practice, the monks chanted a verse known as the Ten Buddha Names Jūbutsumyō ), and this too was a form of buddha-mindfulness. The verse was intoned as part of the daily mealtime ritual and as a merit-making device in the recitation services ( nenju ) that were performed on the 3rd, 8th, 13th, 18th, 23rd, and 28th day of every month.

That Dōgen endorsed and taught the recitation ( nenju ) of the Ten Buddha Names as a form of buddha-mindfulness used to invoke the figures named and to generate merit for dedication in support of specific prayers is clear from a number of his writings on monastic discipline. In the first place, his “Fushukuhanpō” contains a version of the Ten Buddha Names that is to be recited by the rector (ino) and great assembly of monks ( daishu ) before the midday meal: 15 “Birushana Buddha, pure dharma body./Rushana Buddha, complete enjoyment body./Shakamuni Buddha, of trillions of transformation bodies./Miroku Buddha, of future birth./All buddhas of the ten directions and three times./Mahayana Sutra of the Lotus of the Wondrous Dharma./Monjushiri Bodhisattva, of great sagacity./ Fugen Bodhisattva, of the great vehicle./Kanzeon Bodhisattva, of great compassion./All honored bodhisattvas, those great beings./Great perfection of wisdom.” A slightly different version of this formula (one that omits the Lotus Sutra ) also appears in “Ango,” 16 where recitation ( nenju ) of it is used to produce merit ( kudoku ) for dedication (ekō) to “the dragon spirit of the earth ( doji ryūjin ) who is a protector of the true dharma ( goji shōbō),” 17 in support of the following prayer: “We humbly pray that his spiritual luminosity will aid us; that he will widely extend his beneficial protection; that this monastery shall flourish; and that he shall long confer his selfless blessings.” 18 The recitation of”buddha names” in this latter rite has a twofold aim: to invoke the buddhas and bodhisattvas as witnesses to the retreat, and to make a special appeal to the earth spirit ( dojijin ) for protection of the monastery during the three months of the retreat.

-82-

As noted above, Dōgen also calls for recitations ( nenju ) in conjunction with offerings to the earth spirit in “Chiji shingi.” We know from that text, moreover, that he was familiar with the Chinese custom of holding so-called “three- and eight-day recitations” ( sanpachi nenju ) in the sangha hall ( sōdō ). 19 It is most likely, but not certain, that Dōgen implemented that practice at the Daibutsu Monastery ( Daibutsuji ), later known as Eihei Monastery ( Eiheiji) .

Repentance

The term used by Dōgen in Bendōwa that I translate as “repentances” ( shusan ) can be rendered more literally as the “cultivation” or “practice” (shu) of “regret,” “remorse,” “confession,” or “repentance” (san). In East Asian Buddhism, that practice is more commonly referred to as sange , which can be glossed either as “confession/repentance ( san) and remorse/regret ( ge ),” or the “confession/ repentance (san) of transgressions (ge).” Buddhist rituals for effecting confession and the purification that it is said to bring about, moreover, are called “repentance procedures” ( senbō ) or “rites of repentance” ( sangeshiki ). Repentance rites and procedures were a ubiquitous feature of the Song Chinese monastic institution that Dōgen strove to replicate in Japan.

In the first place, according to the Rules of Purity for Chan Monasteries , the ordination ( jukai ) of novice monks ( shami ) in Song China called for repentances, which were brought about by reciting the following verse: “I now entirely repent/all the evil actions I have perpetrated in the past,/arising from beginningless greed, anger, and delusion,/and manifested through body, speech, and mind.” 20 Sincere intonation of this verse, commonly known as the Verse of Repentance (Sangemon) , is said in that text to “purify and heal ( jōji ) the karma ( gō ) of body, speech, and mind.” 21 Secondly, there was in Chinese Buddhist monasteries a bimonthly ritual known as “confession” fusatsu ), which was based on the Indian Vinaya and entailed the gathering of the sangha to recite the Pratimoksa (kaihon) , a list of moral precepts undertaken by individual monks at the time of ordination, and to solicit the public confession of any transgressions. In China, the Pratimoksa most often used was one associated with the Four Part Vinaya (Shibun ritsu); it contained 250 moral precepts for monks. Over time, however, there were efforts to replace the “Hinayana” Pratimoksa with a “Mahayana” version that could be used in rites of confession, such as the bodhisattva precepts ( bosatsu kai ) found in the Sutra of Brahma's Net (Bonmōkyō) .

Dōgen was clearly knowledgeable about these Chinese precedents, and there is every reason to believe that he put them into effect in his own monastic community in Japan. In “Jukai,” Dōgen begins by quoting the section of the Rules of Purity for Chan Monasteries called “Receiving the Precepts” ( jukai ). He does not specifically mention repentances in his own fascicle, probably because

-83-

the section of the Rules of Purity for Chan Monasteries that he is commenting on does not broach the subject. 22 Nevertheless, it is evident from Shōbōgenzō zuimonki , a text traditionally attributed to his disciple Ejō (1198–1280), that Dōgen did endorse the practice of “reciting the precepts sutra” ( kaikyō —i.e., the Sutra of Brahma's Net —“for the purpose of making repentances” ( sange no tame ) prior to receiving the precepts ( jukai ). He insisted, however, that there was no such thing as a violation of the precepts by a person who had not yet formally received them. Once the precepts were received, Dōgen said, any violation of them should be repented. That repentance would wipe out the sin, and the precepts could be administered again. We may infer, therefore, that he embraced the bimonthly rite of “confession” ( fusatsu ), although it is not explicitly called for in any of his extant writings.

The work in which Dōgen most directly states his faith in the power of repentance to mitigate the effects of bad karma is “Sanjigō”: “The retribution for that evil karma of the three times will certainly be felt. Nevertheless, when one acts in a repentant ( sange ) manner, its heavy effects will be turned into light ones. Moreover, that [repentance] will extinguish one's sins ( metsuzai ) and cause one to be purified (sejō).” 23 In a somewhat different version of same text we find: “As the World Honored One has indicated, good and evil karma, once it has been produced, does not fade away even in a hundred, thousand, or ten thousand kalpas. When the causes and conditions ( innen ) are right, its results will certainly be felt. Nevertheless, if one repents ( sange ), one's evil karma will be extinguished, or its heavy effects will be turned into light ones.” As Dōgen understands the dynamic of repentance, it is in itself a good deed that produces merit ( kudoku ) that counteracts, through a process of “purification” ( seijō ) or “extinguishing sins” ( metsuzai ), the otherwise inevitable negative results of bad deeds performed in the past.

Dōgen takes the practice of repentances ( shusan ) to be effective in two ways: (1) as an antidote to evil karma produced in past lives, which most people have no conscious memory of but which manifests itself nonetheless in difficulties that are experienced vividly here and now; and (2) as an immediate remedy to wrong actions that a person has recently committed and is fully aware of:

Dōgen recommends repentance of the first type in “Kesa kudoku”:

Thus, those who receive and hold a kesa should rejoice in their good karma

from previous lives and should not doubt that there has been an accumu-

lation of meritorious deeds and a piling up of virtue ( shakku ruitoku ).

Those who have not yet been able to get [a kesa] should endeavor, quickly

in this present life, to begin to sow the seeds [of good deeds]. Those have

[karmic] obstructions and are unable to receive and hold [a kesa] should-84-

feel ashamed ( zangi ) and repent ( sange ) to all buddhas—i.e., the tathaga-

tas, and to the three treasures—buddha, dharma, and sangha. 24In other words, the good fortune of being able to receive a kesa (i.e., to become a monk) in one's present life is palpable evidence that one has performed good deeds in past lives and is cause for rejoicing. Conversely, an inability to receive a kesa in the present life is a sure sign of bad deeds done in past lives, which should make one feel ashamed and prompt one to make repentances before the buddhas and three treasures.

A good example of the second type of repentance is found in “Jūundōshiki”: “One should not come into the [sangha] hall under the influence of sake. If one forgets this injunction and wishes to make amends, one should make prostrations ( raihai ) and repent ( sange )” 25 Here we see repentance, coupled with prostrations (employed in this instance as a form of apology and a sign of submission to authority), being recommended by Dōgen as a means of making amends for a simple act of rule-breaking. In a similar vein, in “Den'e” he states: “If a feeling of loathing arises when one sees or hears about a kesa , realizing that this will lead to one's own rebirth in evil destinies ( akudō ), one should give rise to a mind of compassion ( hishin); one should feel ashamed ( zangi ) and repent ( sange)” 26 Here, the bad deed committed is a mental one. It is not a physical or a verbal act that is evident to others or overtly breaks any rule of monastic discipline, but it is something of which the person himself is aware, and thus it calls for immediate repentance.

One other aspect of Dōgen's understanding of repentance that is worth considering is the notion that repentances should be made “to,” “before,” or “in the presence of” buddhas and the three treasures. The idea here seems to be that repentance involves confession, and that confession requires a witness or audience if it is to be fully effective. In “Keisei sanshiki”, Dōgen states: “Moreover, when one feels lazy in mind or in flesh, or experiences a lack of faith, one should make repent ( sange ) to past buddhas. When we act in this way, the power of the merit ( kudoku ) of repentances to past buddhas saves us and brings about purification ( seijō ). This merit gives rise to unobstructed pure faith ( jōshin ) and vigor ( shōjin ).” 27 And, somewhat later in the same chapter, he continues: “If one repents ( sange ) in this way, there is sure to be hidden assistance from the buddhas and ancestors ( busso ). With a reflective mind ( shinnen ) and properly deported body ( shingi ), one should confess ( hatsurō ) and tell all to Buddha. The power of confession takes the roots of evil ( zaikon ) and causes them to die out.” 28 Here, Dōgen argues that repentance “to” ( ni ) buddhas of the past, in addition to what might be called the “natural” or “automatic” good effect it produces in accordance with the law of karmic retribution, has the added benefit of enlisting the sympathy of the buddhas and ancestors of the Zen lineage, who will assist the penitent in mysterious and wonderful ways.

-85-

Sutra Reading

The term I translate as “sutra reading” ( kankin ) means to “look at,” “read,” or “think about” (kan) “sutras” ( kyō, kin ). Most Japanese Buddhist dictionaries draw a distinction between reading scriptures quietly, for the purpose of understanding the meaning, and reading scriptures aloud, for the purpose of generating merit for subsequent dedication in an offering ritual. However, there is nothing in Dōgen's use of the term “sutra reading” to suggest that he distinguished between the “intellectual” (reading quietly for meaning) and the “ritualistic” (reading aloud to generate merit) aspects of sutra chanting.

In the Rules of Purity for Chan Monasteries and other monastic rules dating from Song China, and in Chan biographies and discourse records contemporaneous with those texts, the term “sutra reading” ( kankin ) often refers to formal rites in which a group of monks chants scriptures aloud and the resulting merit is dedicated in support of specific prayers. Sutra reading, in those texts, also includes the practice of “revolving reading” ( tendoku ), which entails “turning” (ten) through the pages of sutra books at a speed too fast for actual reading (whether aloud or silently), and to “turning” or rotating the revolving stacks ( rinzō ) in a sutra library, both of which were understood as powerful merit-making devices. Those same texts also make it clear that, at designated times, monks could engage in sutra reading at their individual places in a common quarters ( shuryō); in a sutra repository ( kyōzō ) or sutra hall ( kyōdō); in a sutra reading hall ( kankindō); or in an illuminated hall ( shōdō ), a building outfitted with desks and skylights that was located behind the sangha hall. In those settings, individual monks could select their own reading matter from the bookshelves and were expected to read quietly so as not to disturb their fellows. The range of meanings of “sutra reading” given in modern dictionaries is thus well attested in primary sources dating from Dōgen's day, but it is far from certain that anyone at the time drew such a sharp distinction between “reading quietly for meaning” and “reading aloud to generate merit.” For all we know, monks who engaged in merit-making rituals also contemplated the meaning of the sutras they chanted, and monks who read sutras silently on their own also conceived that activity as one that would bring karmic reward.

In “Kankin” (Sutra Readings), Dōgen takes all of those meanings of the term for granted and gives detailed instructions for how the various rites are to be performed. I quote parts of those instructions here in order to show just how invested Dōgen actually was in merit-making rituals performed for the benefit of lay patrons and rulers, whose donations and political support sustained the monastic institution in both China and Japan. It is also worth noting how integral the practices of burning incense and making prostrations are to the rites of sutra reading prescribed and explained by Dōgen. The following is a translation of relevant sections of “Kankin”:

-86-

In present day assemblies of the buddhas and ancestors ( busso no e ), there

are many types of ceremonial procedures ( gisoku ) for sutra reading

( kankin ). Examples include: donors ( seshu ) visiting a monastery and

requesting that the monks of the great assembly read sutras; sutra reading

in which monks are requested to engage in perpetual revolving ( jōten);

sutra reading initiated by monks of the assembly on their own accord; and

so on. In addition, there is sutra chanting performed by the great assembly

on behalf of a deceased monk.In the case of donors visiting a monastery and requesting that the

monks of the great assembly read sutras… the head seat ( shuso ) and

monks of the great assembly don kesas , enter the cloud hall, 29 go to their

assigned places, and sit facing forward. Next, the abbot enters the hall,

faces the Sacred Monk, bows in gassho, burns incense ( shōkō ), and when

finished sits at his place. Then, have young postulants ( zunnan ) hand

out sutras.…The monks of the great assembly, having received sutras, immediately

open them and read. At this point, the guest prefect ( shika ) at once enters

the cloud hall leading the donor.…The donor goes in before the sacred monk, burns a pinch of incense,

and makes three prostrations ( sanpai ).…Next, the sutra-reading money ( kankin sen ) is distributed. The amount

of money accords with the wishes of the donor. In some cases, goods such as

cloth or fans are distributed instead. The donor himself makes the

distribution, or a steward ( chiji ) makes the distribution. Or, a postulant

makes the distribution. The procedure for distribution is to place the item in

front of the monk, not to put it directly into the monk's hands. When an

allotment of money is placed in front of each individual monk of the as-

sembly, they receive it with a gassho. Allotments of money, alternatively,

may be distributed at the main meal time on the day of the sutra reading.….The aim of the donor's dedication of merit ( seshu ekō ) is written on a

sheet of paper, which is pasted to the left pillar of the Sacred Monk's altar.…There is something called the imperial holiday ( shōsetsu ) sutra reading.

If, for example, the current emperor's birthday is the 15th day of the first

month, then the imperial holiday sutra reading begins from the 15th day of

the preceding 12th month.….From the opening day on, an “establishing ritual site for imperial

prayers” placard (ken shukushin dōjō no hai ) is hung under the eaves on

the east side of the front of the buddha hall.…. Sutra reading in this manner

is continued up until the imperial birthday, when the abbot ascends to the

dharma hall and performs prayers for the emperor. This has been the cus-

tom from ancient times, and even now it is not out of fashion.-87-

Moreover, there is sutra reading that monks engage in of their own

accord. Monasteries have always had communal sutra reading halls

( kankindō ). Sutra reading is done in those halls. The ritual procedures for

that are as given in current rules of purity ( shingi ). 30Given these instructions, and the many similar passages that are found throughout Dōgen's writings on monastic discipline, it is remarkable that modern Japanese scholars have depicted him as a master of “pure Zen” ( junsui zen ) who rejected the “superstitious” ( meishinteki ) practice of merit-making, the “worldly” ( sekenteki ) concern with patronage, and the “overly intellectual” ( rikutsuppoi ) engagement with sutra literature, all of which they take as signs of the “degeneration” of Zen in Song dynasty China. The vision of a “pure,” “original” Zen that informs this view is largely the product of wishful thinking on the part of academic apologists for the Zen schools of modern Japan. The projection of that ideal onto the figure of Dōgen is scarcely defensible, but the aforementioned passage from Bendōwa does give it some measure of credibility.

Dōgen's Interpretations of Rujing's Dictum

As noted above, Dōgen's admonition to “have no recourse whatsoever to burning incense, prostrations, buddha-mindfulness, repentances, or sutra reading” is voiced in Japanese in Bendōwa , but a very similar statement, written in classical Chinese and almost always attributed to Tiantong Rujing, occurs seven other times in his extant writings. In the following pages, I analyze each of the eight occurrences under the heading of the text in which it appears. I treat the texts in question in chronological order, based on the dates given in colophons and other indications of when they were written or recorded. In each case, I pay attention to Dōgen's reasons (stated or implicit) for citing Rujing, because his comments on his teacher's saying must be understood within those contexts.

Hōkyōki

The evidence of this text is especially useful for the purposes of this chapter because it opens a window on what Dōgen thought when he first encountered Rujing's dictum. The “Hōkyō Era” referred to in the title is the Baoqing ( Hōkyō ) era of the reign of emperor Lizong of the Song, which corresponds to the years 1225–1228 31 Modern scholars have questioned whether the text as we now have it was actually written at that time, or whether it was redacted later by Dōgen or subsequent editors. Despite these uncertainties, I am inclined to accept the passage that deals with Rujing's dictum as a veritable record of Dōgen's initial reaction to it, for as we shall see, it does seem to represent an immature point of view

-88-

that differs considerably from his subsequent comments. The setting, presumably, was in the abbot's quarters of the Tiantong Monastery, where the young Japanese disciple had been given the privilege of “entering the room” ( nisshitsu ) of the master:

The reverend abbot ( dōchō oshō ) said, “Studying Zen ( sanzen ) is body and

mind sloughed off ( shinjin datsuraku ). Make no use ( fuyō ) of burning

incense ( shōkō ), prostrations ( raihai ), buddha-mindfulness ( nenbutsu ),

repentances ( shusan ), or sutra reading ( kankin ). Just ( shikan ) sit ( taza )

and that is all.”I respectfully enquired ( haimon)? 32 “What is ‘body and mind sloughed

off'?” The reverend abbot said, “Body and mind sloughed off is seated

meditation ( zazen ). When one just ( shikan ) sits in meditation ( zazen ),

one is separated from the five desires ( goyoku ) and rid of the five obstruc-

tions ( gogai ).”I respectfully enquired, “If you speak of being separated from the five

desires and rid of the five obstructions, then that is the same as what the

Teachings schools ( kyōke ) talk about. 33 Isn't that [what is taught] for the

sake of practitioners of the two vehicles, great and small ( daishō ryōjō)? ”

The reverend abbot said, “Descendants of the ancestral teachers ( soshi no

jison ) do not stubbornly reject what is taught by the two vehicles, great

and small. If a practitioner turns his back on the sagely teachings of the

Tathagata ( nyorai no shōgyō ), how could he possibly claim to be a descen-

dant of the ancestral teachers?”I respectfully enquired, “Doubters these days say that the three poisons

( sandoku ) are the buddha-dharma ( buppō ) and the five desires are the way

of the ancestors ( sodō ). If you eliminate those things, then that is selecting

and rejecting, which is reverting to the same position as the Hinayana

( shōjō )” The reverend abbot said, “If you do not reject the three poisons,

five desires, and the like, then you are the same as those followers of alien

paths ( gedō ) in the land of King Bimbasara and the land of Ajatasatru. As

for us descendants of the buddhas and ancestors, if we eliminate even one

obstruction or one desire, then we benefit greatly. That is precisely the mo-

ment when we encounter ( shōken ) the buddhas and ancestors.” 35Here, Rujing describes “body and mind sloughed off” as a state of trance, achieved in seated meditation, in which the practitioner is free from desires associated with objects of the five senses and rid of the “five obstacles” to wisdom: lust, anger, torpor, agitation, and doubt. As the young Dōgen notes in his follow-up question, those are traditional formulae found in both Hinayana and Mahayana sutras, and the idea that transic meditation ( zen ) should be used to suppress such

-89-

mental afflictions was often criticized in the Zen tradition as a “Hinayana” approach. Rujing chastises his disciple for doubting the value of any Buddhist sutras and emphatically affirms the value of suppressing harmful states of mind by means of meditation.

In this context, Rujing appears to be a conservative Buddhist monk whose admonition to “just sit and that is all” could reflect a view that burning incense, making prostrations, buddha-mindfulness, and repentances are frills that distract one from the all-important practice of seated meditation. Is it possible, then, that Rujing was a purist who held up the “single practice” of zazen as the end-all and be-all of Buddhist cultivation? No, for in the same exchange with Dōgen he stressed the importance of studying the teachings of the Buddha ( bukkyō ), as found in both the Mahayana and the Hinayana sutras.

Elsewhere in Hōkyōki , Rujing criticized the exclusive practice of meditation:

[I, Dōgen] respectfully enquired, “If the great way of the buddhas and

ancestors cannot be confined to a single pigeonhole, why do people insist

on calling it the ‘Zen lineage' ( zenshū)? ” The reverend abbot said, “One

should not refer to the great way of the buddhas and ancestors with a vul-

gar designation like ‘Zen lineage.' The designation ‘Zen lineage' is a false

expression, one-sided and perfidious. It is a name coined by bald-headed

little beasts. This was known by all the ancient men of virtue. It was well

known in the past. Have you ever read Shimens Record of the Monastic

Groves (Ch. Shimenlinjianlu , Jp. Sekimon rinkanroku)? ” [Dōgen] replied,

“I have not read that scripture.” The reverend abbot said, “You would do

well to read through it once. That record explains the matter correctly.”The expression “buddhas and ancestors” ( busso ) was, in Song Chan usage, a synonym for the lineage of Bodhidharma, including the seven buddhas of the past, the 28 Indian ancestors, and the six ancestors in China. Rujing's point was that it is false to characterize Bodhidharma's lineage as one consisting of “practitioners of dhyana” (shūzen) . This is not entirely clear from his dialogue with Dōgen, but it is certain when we consider his remarks in conjunction with the explanation given in Shimen's Record of the Monastic Groves , 36 which he endorsed.

Dōgen did, in fact, follow Rujing's advice to read that text, for he quoted it in “Butsudō”:

Those who are ignorant of this principle carelessly and erroneously speak

of “the treasury of the true dharma eye ( shōbōgenzō ) that is directly trans-

mitted by the buddhas and ancestors ( busso ), and is the wonderful mind

of nirvana ( nehan myōshin ),” recklessly calling this the “Zen lineage”-90-

(zenshū) . They call the ancestral teachers ( soshi ) “Zen ancestors” ( zenso ).

They give the name “Zen follower” ( zensu ) to trainees or call them “Zen

monks” ( zennasu ). Or, they call themselves the “Zen family tradition”

( zenke ryū ). All of these [names] are branches and leaves that are wrongly

viewed as the main roots. Those who recklessly refer to themselves as the

“Zen lineage,” when in fact that designation has never been used in India

or China from ancient times down to the present, are devils who destroy

Buddhism. They are enemies who incur the wrath of the buddhas and an-

cestors. Shimens Record of the Monastic Groves says: “When Bodhidharma

first went from Liang to Wei, he traveled to the base of Mount Song and

took up residence in the Shaolin Monastery, where he did nothing but sit

peacefully facing a wall ( menpeki ). This was not the practice of dhyana

(chan) . People long ago could not fathom his purpose, so they called Bod-

hidharma a practitioner of dhyana (shūzen) . Now, dhyāna (zenna) is but

one of the various practices: how could it alone be sufficient to become a

holy man ( shōnin)? Nevertheless, people of that day took it that way. The

historian also followed along, placing [Bodhidharma's] biography to-

gether with [biographies of] other dhyāna practitioners, putting him a

class with those who tried to make themselves like lifeless wood and dead

ashes. But the holy man does not stop with dhyana (zenna) , nor does he

distance himself from dhyana .” 37The “historian” referred to here is Daoxuan, compiler of the Additional Biographies of Eminent Monks (Xu gaoseng zhuan) , who included a biography of the Indian monk Bodhidharma under the heading of “practitioners of dhyana ” The thrust of Juefan Huihong's complaint in Shimens Record of the Monastic Groves is that Bodhidharma was not merely a meditation master ( zenji ), but the ancestral teacher who transmitted the awakening of the Buddha Sakyamuni from India to China and became the founder of the Chan lineage in that eastern land—a story that Daoxuan did not mention.

In any case, it would appear from his endorsement of the passage from Shimen's Record of the Monastic Groves that Dōgen did not interpret Rujing's “just sitting” as an activity that excluded other Buddhist practices. On the contrary, he subscribed to Huihong's claim that the essence of Bodhidharma's practice was not sitting in meditation, although people of the day mistakenly came to that conclusion when they saw the first ancestor “sitting peacefully facing a wall.” What Huihong meant was that the dharma transmitted by Bodhidharma was not any particular mode of cultivation, but the “buddha-mind” ( busshin ) itself— the awakening of the Buddha Sakyamuni. This raises the possibility that, for Dōgen, “just sitting” does not refer to any particular practice, but rather to an ideal state of mind with which any practice should be engaged.

-91-

Bendōwa

This work, composed in 1231, was one of the first pieces written by Dōgen after his return from China in 1227. Dōgen's aim in Bendōwa was to promote the practice of zazen, which he extolled as the “dharma gate [i.e., the mode of practice] that is easy and joyful” ( anraku no hōmon ) and described as the “marvelous means” ( myōjutsu ) used by all the buddhas and ancestors to “open awakening” ( kaigo ). Dōgen believed that zazen was essential to the true buddha-dharma that had been transmitted from India to China and that it had been neglected by the schools of Buddhism (mainly Tendai and Shingon) that were well established in the Japan of his day. In any case, when modern scholars hold up Dōgen's instruction to “just sit” as the essence of his teaching, it is this text that they generally cite: “From the start ( hajimeyori ) of your consultation ( sanken ) with a wise teacher ( chishiki ), have no recourse ( mochiizu ) whatsoever ( sarani ) to burning incense ( shōkō ), prostrations ( raihai ), buddha-mindfulness ( nenbutsu ), repentances ( shusan ), or sutra reading ( kankin ). Just ( tadashi ) sit ( taza ) and attain the sloughing off of mind and body ( shinjin datsuraku suru koto wo eyo).” 38 Bendōwa is one of only two extant texts in which Dōgen cites Rujing's dictum without attribution to his teacher, and the only instance in which he translates the dictum into Japanese. Nevertheless, for reasons that I explain below, it seems clear that he had his earlier conversations with Rujing in mind when he wrote this text.

Following the passage in which he translates Rujing's dictum, Dōgen responds to a number of questions from dubious or antagonistic interlocutors that directly challenge his admonition to “just sit.” 39 In the words of one such question, “Chanting sutras ( dokkyō ) and buddha-mindfulness are in themselves the causes and conditions ( 3nnen ) of satori; how could simply sitting idling, accomplish that?” 40 Dōgen's reply is harsh: “That you regard the samadhi of all the buddhas—the supreme great dharma—as sitting idly, makes you a slanderer of the Mahayana.” Moreover, he says:

You do not understand the merit ( kudoku ) that one gets by practicing

sutra chanting, buddha-mindfulness, and the like, do you? To think that

simply flapping the tongue and raising one's voice is a meritorious Bud-

dhist act is utter fantasy. As an approximation of the buddha-dharma, it

is far off the mark and headed in the wrong direction. As for opening

the sutra books, if you clearly understand what the Buddha taught about

the procedures of sudden and gradual practice, and if you practice in

accordance with those teachings, you will certainly attain realization.

Squandering your time in thinking ( 3hiryō ) and calculation ( nendo )

cannot compare to the merit that results in bodhi. To try to gain the-92-

buddha-way by idiotically piling up a thousand or ten thousand repeti-

tions of verbal deeds is like pointing the tow-bars of an oxcart north

while intending to head for the kingdom of Yue [in the south]. Or, it is

like trying to put a square peg into a round hole. To be in the dark about

the way of practice while perusing [Buddhist] scriptures is like a person

who forgets to take some medicine because he is reading the doctor's

instructions for it: there is no benefit at all. To voice words incessantly,

like frogs who croak day and night in the paddy fields in spring, is also

without benefit. 42Although the criticisms of sutra chanting and buddha-mindfulness—i.e., repeatedly calling the name of Amida or other buddhas—found in this passage are certainly harsh and even mocking in tone, what Dōgen condemns are not those practices per se, but rather the misguided pursuit of them under the influence of deluded thinking ( shiryō ) and calculation ( nendo ). What is idiotic, he says, is the recitation of sutras in the belief that this will lead, in some automatic or mechanical way, to a piling up of merit that will result in awakening. If, on the other hand, one grasps the true meaning of the sutras and practices accordingly, one will reap a genuine benefit.

The distinction that Dōgen draws between engaging in conventional Buddhist practices with a deluded mind that is greedy for imagined benefits and engaging in those same practices with a mind that is free from such “thinking and calculation” is clear and compelling, but it does create a problem for his overall argument in Bendōwa: Is not the practice of zazen, too, equally idiotic and pointless if undertaken with a deluded mind that expects to gain some imagined satori or counts up the hours spent sitting as if they were cash deposits in some spiritual bank? Dōgen implicitly concedes that point in his response to another question, which reads as follows:

[I now see that] people who have not yet realized and understood (shōe)

buddha-dharma may pursue the way in seated meditation ( zazen

bendō ) and be able thereby to attain realization (3hō). But what can

those who have already clarified the true dharma of Buddha expect to

gain through zazen?Dōgen's rejoinder is that anyone who engages in zazen as a means to gain awakening (in which case, having reached that goal, the practice of zazen would no longer be necessary) is laboring under the deluded view of a non-Buddhist ( gedō no ken ). The correct understanding, he says, is that practice and realization ( shushō ) are identical (ittō): even a beginner's pursuit of the way is the complete embodiment of innate realization ( honshō ), so the right attitude with which to

-93-

engage in practice is not to expect any sort of realization to occur that is anything other than practice itself. 44 With these remarks, Dōgen concedes that zazen, just like any other Buddhist practice, can be approached in a misguided way that renders it ineffectual or even counter-productive.

If that is the case, however, then what makes zazen different from, or preferable to, any other practice? Any mode of Buddhist cultivation, it would seem, could be an embodiment of innate realization if it was undertaken with the correct understanding, and could be like “trying to put a square peg into a round hole” if it was not.

Elsewhere in Bendōwa , Dōgen is at pains to argue that the zazen he is calling for is not the same as the concentration ( jō ) that is the second of the three modes of training ( sangaku ), nor the same as the perfection of meditation ( zendo ) that is the fifth of the six perfections (rokudo). 45 Although he does not mention Rujing or Shimen's Record of the Monastic Groves in this context, it is clear that he is again echoing Juefan Huihong's (a.k.a., Shimen's) point that Bodhidharma was no mere practitioner of meditation, that being but one of the six perfections, but was the transmitter to China of the “unsurpassed great dharma ( mujō no daihō ), the treasury of the true dharma eye ( shōbōgenzō ), which is the single great matter ( ichi daiji ) of the Tathagata.” Here, Dōgen wants to claim that the zazen transmitted by the so-called Zen lineage of ancestral teachers is not one the six practices of a bodhisattva, any one of which can in principle be undertaken with either a correct or an incorrect understanding of the relationship between practice and realization, but rather a name for the awakened buddha-mind itself, which by definition is never caught up in delusion. This claim does distinguish zazen from all conventional Buddhist practices (including the practice of meditation itself), but it puts Dōgen in the position of contradicting himself, for “sitting” in this abstract sense is not really a “dharma gate” (a mode of practice) or a “marvelous means” at all.

Eihei kōroku, Volume 9.85

Volume 9 of the Eihei kōroku is a collection of Dōgen's verse commentaries on old cases ( juko ), which seem to have been composed up until 1236. Here, we find Rujing's dictum held up as an “old precedent” ( kosoku kōan ) that Dōgen commented on with a poem written in four phrases of seven Chinese characters each:

Reverend Tiantong said, “Here in my place ( gakori ), make no use of

burning incense ( shōkō ), prostrations ( raihai ), buddha-mindfulness ( nen-

butsu ), repentances ( shusan ), or sutra reading ( kankin ). Just ( shikan ) sit

( taza); only then will you get it.” Dōgen said,-94-

The turtle keeps hands and head to himself, but he is not unable to pick

things up;/“Of,” “?,” “this,” and “is” are lost and later gained./When

dragons and snakes are mixed up together, they still look like dragons and

snakes;/although they sit together with coiled bodies, from the beginning

[dragons have] wings.Because the verse by Dōgen is presented as a commentary, in principle it tells us what he thinks about Tiantong Rujing's saying, but being a poem its message is hidden in a skein of metaphors that need to be unraveled if we are to make any sense of it.

In India, the image of a turtle with head and limbs drawn into its shell was a symbol of meditative trance, in which the five sense are entirely “pulled in” or disconnected from sense objects. The Chinese characters that I translate as “of” (shi), “?” (ko), “this” (sha), and “is” ( ya ) represent parts of speech and grammatical markers that are crucial for discursive thinking and writing. What Dōgen is saying in the first pair of lines, therefore, is that his teacher Tiantong Rujing was a master of transic meditation who withdrew into a realm beyond the reach of verbal representation, but who was able nevertheless to deal effectively with the world around him and to communicate skillfully using language. The second pair of lines evokes the image of a group of monks sitting in rows on the platforms in a meditation hall. Some are “dragons”—a standard metaphor for awakened masters, while others are “snakes”—impostors who pretend to have an understanding that they actually lack. The mere sight of a group of monks practicing zazen, all of them presumably deep in meditative trance, would not give the observer any clue as to which were awakened and which still caught up in delusion. Dōgen, nevertheless, says it is clear which are which, because the dragons have wings while the snakes do not. The presence or absence of “wings,” in this context, must be something that is judged by how the monks act and communicate when they emerge from trance or “come out of their shells.” One point of Dōgen's verse is that Rujing's dictum shows him to be a true dragon among a multitude of snakes.

Beyond that, does the verse tell us what Dōgen thinks Rujing's dictum means? That is far from certain, but I will hazard an interpretation. The image of “a turtle keeping hands and head to himself” while nevertheless being “able to pick things up” may represent an attitude of mental detachment in which one makes use of conceptual thought (or language) without being caught up in the delusion that the things (hō) named in language actually exist as discrete, independent entities. Dōgen could be comparing Rujing's admonition to “just sit” to the restrained mental posture of the “turtle,” in which case the injunction against burning incense, prostrations, etc., is not to be taken literally as a rejection of those practices, but only as a caution not to engage in them in a deluded manner.

-95-

Eihei kōroku, Volume 1.33

The following passage is the first part of a sermon that Dōgen delivered from the abbot's high seat in the dharma hall during a convocation ( jōdō ) held at Kōshōji in 1240.

Those who understand the buddha-dharma and attain spiritual powers

( jinzū ) are the ancient buddhas and ancestors ( busso ). To become a bud-

dha and make oneself into an ancestor ( jōbutsu sakuso ) is not attained

easily. However, those who attain spiritual powers are called experienced

and venerable ( rōrō ), and those who understand the buddha-dharma are