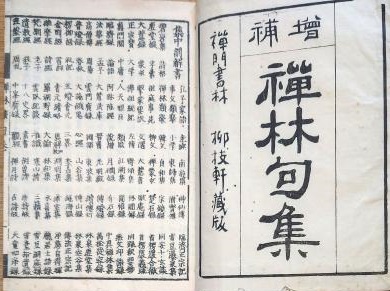

禪林句集 Zenrin-kushū

Zen Phrase Books

(English:) Phrases from the Zen Forest, Collection of Sayings from the Zen Forest, Zen Sangha Phrase Collection

(Magyar:) A Zen-erdő összegyűjtött mondásaiból

attributed to 東陽英朝 Tōyō Eichō (1428-1504)

Tartalom |

Contents |

Zenrin kusú [5 vers] Zenrin Kusu [25 vers] Zenrin kusú [160 vers] |

PDF: A Zen Forest: Sayings of the Masters (1981) ZEN SAND: Zenrinkushu PDF: Poetry and Zen: Letters and Uncollected Writings of R. H. Blyth

Selections from A Zen Phrase Anthology 久須本文雄 Kusumoto Bun'yū (1907-1995) |

![]()

Zenrin Kushû

“A Collection of Phrases from the Zen

Garden,” a compilation of 6,000 quotations

drawn from various Buddhist

scriptures, Zen texts, and non-Buddhist

sources. At least since the time of the

eighteenth-century Rinzai reformer,

Hakuin Ekaku (1685–1768), Rinzai

masters and students have relied upon

the Zenrin Kushû as a resource for

jakugo, or capping verses, which

are used as a regular part of kôan

practice. Portions of the text have been

translated into English in Sasaki and

Miura’s The Zen Kôan and Shigematsu’s

A Zen Forest.

The Zenrin Kushû is based upon an

earlier anthology of 5,000 Zen phrases

known as the Ku Zôshi, compiled by

Tôyô Eichô (1438–1504). Tôyô drew his

material from sutras, recorded sayings

of Chinese Zen masters, Taoist texts,

Confucian texts, and Chinese poetry. He

arranged the phrases according to

length, beginning with single-character

expressions, continuing with phrases of

two characters through eight characters,

and interspersing parallel verses of

five through eight characters. Tôyô’s

work circulated in manuscript form for

several generations until the seventeenth

century. At that time, a person

using the pen name Ijûshi produced an

expanded version of the text that was

first published in 1688 under the title

Zenrin Kushû.

English versions:

Ruth Fuller Sasaki: Zen Dust (210 phrases)

Shigematsu Sōiku: A Zen Forest (1,234 verses)

Robert E. Lewis: The Book of the Zen Grove (631 verses)

Victor Sōgen Hori: Zen Sand (4,022 phrases)

PDF: A Zen Forest: Sayings of the Masters (1981)

Translated, with an introduction, by Sōiku Shigematsu

The Book of the Zen Grove Phrases for Zen Practice

by

Zenrin R. Lewis, 1996, 144 p.

This book is an English translation of Shibayama Zenkei Roshi's Zenrin Kushu. It contains the original Chinese phrases together with English, and Japanese translations.

Zenrin R. Lewis (Hg.): Der Zen-Wald. Koan-Antworten aus dem Zenrin kushu. Chinesisch-Deutsch. Übertragen von Guido Keller. Angkor Verlag, 2012, 172 S.

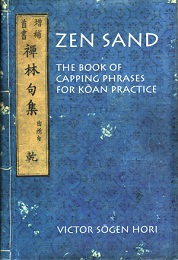

PDF: ZEN SAND: The Book of Capping Phrases for Kōan Practice

Translated by Victor Sōgen Hori

Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press; Bilingual edition, 2010, 764 pages

Introduction: Capping-Phrase Practice in Japanese Rinzai Zen, pp. 3-4

1. The Nature of the Rinzai Kōan Practice, pp. 5-15

2. The Steps of Kōan Practice, pp. 16-29

3. Literary Study in Kōan Practice, pp. 30-40

4. The Kōan and the Chinese Literary Game, pp. 41-62

5. The History of Zen Phrase Books, pp. 62-90

6. Guide to Conventions and Abbreviations, pp. 91-98

http://muse.jhu.edu/books/9780824865672?auth=0

http://nirc.nanzan-u.ac.jp/en/publications/nlarc/zen-sand

A complete and searchable list of all the Chinese verses in Zen Sand

http://nirc.nanzan-u.ac.jp/en/files/2012/12/Zen-Sand-verses.pdfTranslating the Zen Phrase Book by G. Victor Sōgen Hori

Nanzan Bulletin, 23/1999, pp. 44-58.

http://www.thezensite.com/ZenEssays/HistoricalZen/translating_zen_phrasebook.pdf

https://nirc.nanzan-u.ac.jp/nfile/1913PDF: Zen Koan Capping Phrase Books: Literary Study and the Insight “Not Founded on Words or Letters”

by Victor Sōgen Hori

Zen Classics: Formative Texts in the History of Zen Buddhism (2006), pp. 171-214.Zen Sand: The Book of Capping Phrases for Kōan Practive

Reviewed by Jiang Wu

http://philzenlibrary.files.wordpress.com/2010/03/zen-sand_-the-book-of_capping-phrases-fo-pholloway.pdfVictor Sogen Hori: Zen Sand: The Book of Capping Phrases for Koan Practice

University of Hawai'i Press, Honolulu, 2003, p. 764

review by Vladimir K., October, 2003

http://www.thezensite.com/ZenBookReviews/Zen_Sand.htmlThe study of koans in Western Zen has omitted one essential element common in Japanese Rinzai practice—the ‘capping phrase' or jakugo (‘to append a phrase'). When a Japanese monk has had an insight into a koan, the master will ask for a jakugo , a phrase or verse that expresses the insight the monk has had. To find this phrase, the monk will consult one or a number of phrase books (kushu) searching for an adequate line or phrase to present to the master. In the advanced stages of koan study, the monk will also present written explanations (kakiwake) and Chinese-style poetry (nenro). According to Hori, “Such literary study is not merely an incidental part of koan study” (p.4) but an essential training for Rinzai monks. But if Zen practice is the attainment of nonrational, direct pointing at the mind, ‘not founded on words and letters', what role does jakugo play and where did this literary tradition in Zen come from? The lengthy introduction to Zen Sand provides an insight into these questions.

This is a remarkable book of immense importance to the ongoing project of the transmission of Zen to the West. Hori has compiled and translated two capping-phrase books, Shibayama Zenkei's (1894-1974) Zenrin kushu and Tsuchiya Etsudo's (1899-1978) Shinsan zengoshu , resulting in the largest modern collection of capping phrases in any language, 4,022 phrases, and is second in size only to Ijushi's Zenrin kushu , published in 1688, which has 4,380 phrases. Furthermore, Hori has included for each verse the Chinese characters, a Japanese kanji reading, an English translation, an annotation of sources (where available), a reference to the original phrase book and an indication if a particular word shows up in the glossary. Chinese names are given in the Wade-Giles romanization. The whole volume is fully indexed and has an invaluable glossary of nearly 100 pages which helps explain some of the metaphors and allusions used in the phrases. It has, as well, a full bibliography and a most valuable 87-page introduction which carefully explains and discusses the literary tradition of Zen practice. The full introduction is available for downloading in Acrobat.pdf format. (Hori has also written about his experiences in translating the Zen Sand. This was published before Zen Sand and you can read it here.)

In his introduction, Hori points out that Rinzai koan practice is “like all Buddhist practices”, (p.5) a religious practice. While religious experience may be indescribable (and Zen does have a history of discouraging discussion of Zen experience), this does not necessarily mean that the experience is devoid of any intellectual activity, just that any language about the experience can be meaningful only to those who have shared the experience. Without such an experience, Zen language appears nonsensical and illogical, especially in koans. What's missing is a reference point. If we are not privy to the reference made in the language, then it would appear to have no meaning. For example, how could you describe the taste of chocolate to one who has never tasted it? The best one could do is to use analogy, metaphor and description but the listener would still not know how chocolate really tasted until it was placed in the mouth; likewise with the Zen experience.

The use of jakugo in Zen practice goes back at least to the Sung Dynasty (AD 960 - 1270). The Hekigan-roku has examples of jakugo in Engo's capping phrases to Setcho's verse on the main case. Likewise, Mumon's four line verses in the Mumonkan are jakugo . Originally, jakugo were written by the monks themselves but gradually they were collected in books for reference and verses from Chinese poetry, Buddhist sutras, Confusion classics, historical writings and Taoist works were included. The result is a collection that plunders classical Chinese history, philosophy, poetry and literature as well as Buddhist texts.

What has never been adequately explained is where the koans came from in the first place. Hori advances a unique theory of the origin of koans and jakugo as having a background in classical Chinese “literary games” but in the service of Zen insight. These Chinese literary games pre-date the arrival of Ch'an/Zen in China and were an intellectual competition between players using highly allusive language to say something without actually saying it and thereby tripping up the opposition. Hidden meanings, inside jokes, obscure references and just plain cleverness were all part of the game. For Hori, the use of jakugo in Japanese Rinzai is a return to the origins of koans. Hori's theory goes some way to explaining the humour, the acid tongue, the wit and the highly allusive language found in koan collections. One-the-spot improvisations, a feature of these games, is also highly valued in Zen dialogues, as is “turning the other's spear against him” where one player (or Zen monk) recognizes the other's strategy and turns it around to defeat the other (sometimes called "Dharma combat" in Zen).

Following from this view of Zen koans and the tradition behind them, Hori claims that “the notion of a mind-to-mind transmission outside of language did not originate with Zen [but]…Zen adopted it from Chinese literary culture.” (p. 56) The author sees the concept of wu wei (non-action) as originating not in Zen but in a classical Chinese culture that pre-dates Ch'an/Zen. As he says, “the entire educated world of China saw the epitome of learned discourse as one in which the partners were so learned that they communicated more through silence than through words.” (p. 57) The significance of this for Zen practice is understanding that Zen does not mean abandoning words and language, but on mastering them to the extent that one can communicate “mind-to-mind”.

But it would be wrong to think that Hori sees Zen koan practice as nothing more than some literary game. He is careful to reiterate that insight into a koan is fundamentally a religious matter. “The koan is both the means for and the realization of, a religious experience that finally consumes the self.” (p. 52) Victor Sogen Hori's own background reaffirms this understanding. He received a doctoral degree in philosophy from Stanford University in 1976, the same year he was ordained as a Zen monk. He subsequently spent thirteen years studying Rinzai in Japan, returning to academic life in 1990. He is currently professor of Japanese religions in the Faculty of Religious Studies, McGill University.

This beautiful volume is recommended unreservedly. It is a major contribution to Western zen for academics and practitioners alike. The glossary is most helpful and I found Hori's discussion of the origins of koans and jakugo fascinating and providing new insights into an ancient practice. The academic standard is of the highest order. Thoroughly researched and referenced, it will undoubtedly become a classic in the English-speaking Zen world.

ZENRINKUSHU

http://web.archive.org/web/20120302073712/http://boozers.fortunecity.com/brewerytap/695/Zenrinkushu.html

Anthology "Zenrinkushu" was compiled by Eicho (1429-1504), a

disciple of Secco of Myoshinji. The items (4000 in all) are

collected from about two hundred books, including various Zen

writings: "The Analects", "The Great Learning", "The Doctrine of

the Mean", "Mencius", "The Odes", "Laotse", "Chuangtse", "The

Hekiganroku", "Mumonkan", "Shinjinmei", the poetry of Kanzan,

Toenmei, Toho, Ritaihaku, Hakurakuten. The first 73 of the

following are taken from the book:

R.H.Blyth, "Haiku", vol.1, pp. 25-33.

Cf.

PDF: Poetry and Zen: Letters and Uncollected Writings of R. H. Blyth

edited with an introduction by Norman WaddellThese translations from the Zenrinkushū, “Anthology of Phrases for

the Zen Forest,” a collection of poetic phrases used in Rinzai Zen

koan study compiled by the Myōshin-ji priest Tōyō Eichō (1428–

1504), appeared serially in The Young East 12, no. 46 (Summer

1963); 12, no. 47 (Autumn 1963); 12, no. 48 (Winter 1963); 13, no. 49

(Spring 1964); and 13, no. 50 (Summer 1964).

The raindrops patter on the bamboo leaf, but these are not tears of grief;

This is only the anguish of him who is listening to them.

The voice of the mountain torrent is from one great tongue;

The lines of the hills, are they not the Pure Body of Buddha?

It is like a sword that wounds, but cannot wound itself;

Like an eye that sees, but cannot see itself.

Words do not make a man understand;

You must get the man, to understand them.

To be able to trample upon the Great Void,

The iron cow must sweet.

It is like a tiger, but with many horns;

Like a cow, but it has no tail.

Meeting, the two friends laugh and laugh;

In the grove, fallen leaves are many.

The cock announces the dawn in the evening;

The sun is bright at midnight.

The voice of the fountain after midnight;

The colours of the hills at sunsetting.

The cries of the monkeys echo through the dense forest;

In the clear water, the wild geese are mirrored deep.

The wooden cock crows at midnight;

The straw dog barks at the clear day.

Mountains and rivers, the whole earth, --

All manifest forth the essence of being.

The wind drops but the flowers still fall;

A bird sings, and the mountain holds yet more mystery.

All waters contain the moon;

Not a mountain but the clouds girdle it.

Entering the forest, he does not disturb a blade of grass;

Entering the water, he does not cause a ripple.

One word determines the whole world;

One sword pacifies heaven and hell. (WZ-153)

The plum tree, dwindling, contains less of the spring;

But the garden is wider, and holds more of the moon.

The tree manifest the bodily power of the wind;

The wave exhibits the spiritual nature of the moon.

Go out, and you meet Shakyamuni;

Go home, and you meet Miroku Buddha.

From of old there were not two paths;

"Those who have arrived" all walked the same road.

Draw water, and you think the mountain are moving;

Raise the sail, and you think the cliffs are on the run.

In the vast inane there is no back or front;

The path of the bird annihilates East and West.

Only seeing the sharpness of the awl;

Not knowing the squareness of the stone-chisel.

This night the Buddha entered Nirvana;

It was like firewood burned utterly away.

One leaf, a Shakyamuni;

One hair, a Miroku.

To preserve life, it must be destroyed;

When it is completely destroyed for the first time there is rest.

Perceiving the sun in the midst of the rain;

Ladling out clear water from the depths of the fire.

When a cow of Kaishu eats mulberry leaves,

The belly of a horse in Ekishu is distended.

To have the sun and moon in one's sleeve;

To hold the universe in the palm of one's hand.

If you do not get is from yourself,

Where will you go for it?

The water a cow drinks turns to milk;

The water a snake drinks turns to poison.

Many words injure virtue;

Wordlessness is essentially effective.

Though we lean together upon the same balustrade,

The colours of the mountain are not the same.

How good it is that the whole Body

Of Kwannon enters into the wild grasses!

Taking up one blade of grass,

Use it as a sixteen-foot golden Buddha.

The blue hills are of themselves blue hills;

The white clouds are of themselves white clouds.

If you have not read "The Analects",

How can you know the meaning of Zen?

Heat does not wait for the sun, to be hot,

Nor wind the moon, to be cool. (WZ-118)

Nothing whatever is hidden;

From of old, all is clear as daylight.

The old pine-tree speaks divine wisdom;

The secret bird manifests eternal truth.

Seeing, they see not;

Hearing, they hear not.

Just one pistil of the plum flower, --

And the three thousand worlds are fragrant.

Unmon's staff is too short;

Yakusan's baton is too long.

Every man has beneath his feet

Ground enough to do zazen on.

If you do not kill him,

You will be killed by him.

You may wish to ask where the flowers come from,

But even Tokun [the god of spring] does not know.

If you meet an enlightened man in the street,

Do not greet him with words, nor with silence.

Where the interplay of "is" and "is not" is fixed,

Not even the sages can know.

The water before, and the water after,

Now and forever flowing, follow each other.

What is written is of ages long ago,

But the heart knows all the gain and loss.

There is no place to seek the mind;

It is like the footprints of the birds in the sky.

Sitting quietly, doing nothing,

Spring comes, grass grows by itself.

Above, not a piece of tile to cover the head;

Beneath, not an inch of earth to put one's foot on.

The mouth desires to speak, but the words disappear;

The heart desires to associate itself, but the thoughts fade away.

If you wish to know the road up the mountain,

You must ask the man who goes back and forth on it.

Simply you must empty "is" of meaning,

And to take "is not" as real.

One mote flying up dims the sky;

One speck of dust covers the earth.

Is there anything to compare with wearing of clothes and eating of food?

Beyond this there is no Buddha or Bodhisattva. (WZ-152)

To know the original Mind, the essential Mature,

This is the great disease of (our) religion. (WZ-152)

The Tathagata's True-Law Eye-Treasury, --

It is just like two mirrors reflecting each other.

It cannot be attained by mind;

It is not to be sought after through mindlessness. (WZ-136)

It cannot be created by speech;

It cannot be penetrated by silence.

The geese do not wish to leave their reflection behind;

The water has no mind to retain their image. (WZ-181)

Falling mist flies together with the wild ducks;

The waters of autumn are of one colour with the sky.

The old tree leans over the waves, its cold image swaying;

Mist hovers above the grass, the evening sun fading.

If you do not believe, look at September, look at October,

How the yellow leaves, fall, and fill mountain and river.

Above the bare boughs of a thousand hill, a vast, distant sky;

Over the path of the river, a radiant moon.

When Buddha thrust out his three inches of iron [his tongue],

Then for the first time were known the swords and spears of the world.

I went there and came back; it was nothing special;

Mount Ro wreathed in mist; Sekko at high tide.

Planting flowers to which the butterflies come,

Daruma says, "I know not". (WZ-171)

The broken mirror will not again reflect;

Fallen flowers will hardly rise up to the branch.

When spring comes, many visitors enjoy themselves at the temple;

When the flowers fall, only the monk who shuts the gate is left.

I know not from what temple

The wind brings the voice of the bell.

Yuima is disinclined to open his mouth,

But on the bough, a single cicada is chirping.

He holds the handle of the hoe, but his hands are empty;

He rides astride the water-buffalo, but he is walking. (Blyth, H-1-183)

When moving in all directions,

Even the Buddha cannot discourse upon it. (H-1-185)

A long thing is the long body of Buddha;

A short thing is the short body of Buddha. (H-1-187)

Alive, I will not receive the Heavenly Halls;

Dead, I fear no Hell. (H-1-205)

The blue hills are by their nature immovable;

The white clouds of themselves come and go. (H-1-246)

In the garden shines the moon, but there is no shadow beneath the pine-tree;

Out side the balustrade, no wind, but the bamboos are rustling. (H-2-443)

In face, the bamboos of Chia, peach-blossoms;

At heart, thorns and briers of Ts'an-tien. (H-2-441)

In the scenery of spring, nothing is better, nothing worse;

The flowering branches are of themselves, some long, some short.

(H-2-580, WZ-125)

I gazed to my heart's content at the scenery of Shosho,

Painting even my own boat into the picture. (H-3-706)

The three worlds are only mind;

All things are simply perception. (H-3-789)

The water flows, but back to the Ocean;

The moon sinks, but is ever in Heaven. (H-3-943)

Breaking off a branch of crimson leaves, and writing thoughts of autumn;

Plucking the yellow flowers, and making them the evening meal. (H-4-1097)

Stones rise up into the sky;

Fire burns down through the water. (ZEL-12)

Ride your horse along the edge of a sword;

Hide yourself in the middle of the flames. (ZEL-12)

Blossoms of the fruit tree bloom in the fire;

The sun rises in the evening. (ZEL-12)

The clear streams never ceases their flowing;

The evergreen trees never lose their green. (ZEL-28)

The flowers abloom on the hill are like brocade;

The brimming mountain lake is black as indigo. (ZEL-28)

Day after day the sun rises in the east;

Day after day it sets in the west. (ZEL-29)

Ever onwards to where the waters have an end;

Waiting motionless for when the white clouds shall arise. (ZEL-35)

Walking up the mountain path I came to the source of the stream;

While sitting in quietude I watch how the clouds rise. (Suzuki, EZ-3-43)

We sleep with both legs stretched well out;

For us, no truth, no error exist. (ZEL-37)

For long years a bird in a cage;

Now, flying along with the clouds of heaven. (ZEL-37)

Buddha was silent, but explained everything;

Kasho heard nothing, but apprehended all. (ZEL-151)

Receiving trouble is receiving grace;

Receiving happiness is receiving a trial. (ZEL-277)

Scoop up the water and the moon is in your hands;

Hold the flower and your clothes are scented with them. (ZEL-279)

The mirror reflects the tapers of the golden pavilion;

The mountain echoes the bell of the moon-tower. (ZEL-291)

Summer at its height -- and snow on the rocks!

The death of winter -- and the withered tree blooms! (ZEL-344)

On Mount Wu-t'ai the clouds are steaming rice;

Before the ancient Buddha hall, dogs piss at heaven. (WZ-189)

One, two, three, four, five, six. (ZZC-2-202)

Clouds are moving;

Waters are swelling. (ZZC-2-202)

Rabbits and horses have horns;

Cows are sheep have none. (ZZC-2-203)

Navigating a ship on dry ground,

Riding a horse through the empty air. (ZZC-2-203)

Fine rain wets the garment, but though we gaze it cannot be seen;

The flowers quietly fall to the ground, but though we listen,

we cannot hear it. (ZZC-2-203)

****************************************************************

Selections from A Zen Phrase Anthology

Translated by Ruth Fuller Sasaki

In: Zen Dust, New York, 1966, pp. 79-122.

4

The willows are green, the flowers are red.

I alone walk in the red heavens.

To lose one's money and incur punishment as well.

A second offence is not permitted.

He who knows the law fears it.

To take what's coming to you and get out.

To know, yet deliberately to transgress.

Briskly and spiritedly.

To acknowledge a thief as one's child.

To cover one's ears and steal the bell.

Words fail.

To hide a spear within a smile.

It can't be swallowed, it can't be spitted out.

A dragon's head, and a snake's tail.

The sacred tortoise drags its tail.

The family is broken up, the house destroyed.

The leper drags his friends along with him.

To work hard and accomplish nothing.

He's fallen deep in the weeds.

Guest and host are clearly distinguishable.

5

Fragrant, the valley's single plum flower.

At every step the pure wind rises.

Even a good thing is not so good as nothing.

He doesn't recognize the smell of his own dung.

A beloved son is not ugly.

To gouge out healthy flesh and make a wound.

He made good use of his father's money.

In the pot sun and moon shine eternally.

There's no cool spot in a cauldron of boiling water.

Though the frog leaps, it can't get out of the bushel.

The poor man thinks about his unpaid debts.

To wash a clod of earth in the mud.

The single-saucer lamp within the room.

In a good talk, don't explain everything.

Pushing down the ox's head, he makes it eat grass.

A skillful craftsman leaves to traces.

When the earth is fertile, the eggplants are large.

The extremity of grief.

There is no waste in the Imperial Court.

White clouds hold lonely rocks in their embrace.

2x5

Scoop up water, and the moon is in your hands;

Toy with flowers, and their fragrance scents your garments.

A thousand grasses weep tears of dew;

A single pine tree murmurs in the breeze.

Seeking fire, you find it with smoke;

Carrying spring-water, you bring it back with the moon.

Ten years of dreams in the forest!

Now on the lake's edge laughing, laughing a new laugh.

The ten directions are without walls;

The four quarters are without gates.

Who can know that far off in the misty waves

Another yet more excellent realm of thought exists?

For ten years I couldn't return;

Now I've forgotten the road by which I came.

Only I myself can enjoy it;

It is not suitable to present to you.

The murmuring of the spring as the night deepens;

The colouring of the hills as the sun goes down.

Where the sun and moon do not reach,

There is marvelous scenery indeed!

Singing his poem, he rolls the bamboo blind high;

Having finished his nap, he parches the tea leaves dark.

The dragon-hum in the dead tree,

The eyeball in the dry skull.

A hidden bird twitters "Nam, nam";

Taking leave of the cloud, I enter the scattered peaks.

Autumn wind, blowing over the waters of the Wei,

Covers all Ch'ang-an with falling leaves.

A light breeze stirs the lonely pine,

The sound is more pleasant heard close by.

Now that I've shed my skin completely,

One true reality alone exists.

When you're really master of the myriad forms,

Throughout the four seasons there's no withering, no decay.

I meet him, but know not who he is;

I converse with him, but do not know his name.

When you recognize (Mind's) nature while according with its flow,

There's no more joy, nor is there any sorrow.

The five petals of the one flower open,

And the fruit of itself is ripe.

6

Before, three times three; behind, three times three.

Stupidly steadfast, steadfastly stupid.

He displays a sheep's head but sells dogs flesh.

The well looks at the ass; the ass looks at the well.

Riding backwards on an ox, I enter the Buddha-hall.

A good son doesn't use his father's money.

Honest speech is better than a red face.

An angry fist does not strike a smiling face.

Rice in the bawl, water in the bucket.

The flute without holes is the most difficult to blow.

Three m en testified about the tortoise, so that makes it a turtle.

The arm doesn't bend outward.

Going to hell with the speed of an arrow.

Better to see the face than to hear the name.

The haze mist does not stay the plum flower's fragrance.

Don't display the family skeletons in public.

Astride a blind ass he pursues a fierce tiger.

He's hitting at a ball on swift-flowing water.

The good merchant hides his possessions well and appears to have nothing.

Mr. Tsang's head is white; Mr. Hai's head is black.

2x6

Believing this to be radiance and spirituality,

He is content to run is front of asses and follow after horses.

The cold kills you with cold, the heat kills you with heat.

Above, there isn't a piece of tile to cover his head;

Below, there isn't an inch of earth for his to stand on.

When a mouth want to speak about it, words fail;

When the mind seeks affinity with it, thought vanishes.

Sun and moon cannot illumine it completely;

Heaven and earth cannot cover it entirely.

Though we're born of the same lineage,

We don't die of the same lineage.

When we're reviling on another, you may give me tit for tat;

When we're spitting at one another, you may spew me with slobber.

The deer-hunter doesn't see the mountains,

The miser doesn't see men.

Bodhidharma didn't come to Chine,

The Second Patriarch didn't go to India.

Breathing in, he does not stay in the realm of the skandhas;

Breathing out, he is not concerned with the myriad things.

Last year's poverty was not real poverty;

But this year's poverty is poverty indeed.

The devas find no path on which to strew flowers;

The heretics secretly spying find nothing to see.

Even Li Lou cannot discern the true form;

How, then, can Shih K'uang distinguish the subtle tune?

Last year's plum and this year's willow --

Their color and fragrance are as of old.

Having cut off the top of Vairocana's head,

I don't know that any buddha or patriarch ever existed.

As the limits of heaven the sun rises and the moon sets;

Beyond the balustrade the mountains deepen and the waters become chill.

He sees only the winding of the stream and the twisting of the path;

He does not know that already he is in the land of the immortals.

He who would understand the meaning of Buddha-nature

Must watch for the season and the causal relations.

Every voice is the voice of Buddha,

Every form is the Buddha-form.

The wild goose has no intention of leaving traces,

The water has no thought of engulfing reflections.

7

The instant you speak about a thing you miss the mark.

How can the mountain-finch know the wild swan's aspiring?

The eight-cornered mortar rushes across the sky.

The badges and the white bull emit a glorious radiance.

With no bird singing the mountain is yet more still.

In the spring beyond time the withered tree flowers.

When the snowy heron stands in the snow, the colors are not the same.

A second try is not worth half a cash.

A pair of monkeys are reaching for the moon in the water.

How many times for your sake have I gone down into the blue dragon's cave!

When pure gold enters the fire, its color becomes still brighter.

Endlessly rise the distant mountains, blue heaped upon blue.

You must see for yourself the red-flowers drenched in moonlight.

The marks are on the balance-arm, not on the scale-pan.

My single peal of laughter startles heaven and earth.

To turn a somersault on a needle's point.

The garrulous reverend can't open his trap.

Each time you bring it up, each time it is new.

The rat that entered the money box is as its wit's end.

Eternally and everlastingly it is revealing itself to men.

2x7

You've drunk three cups of wine

At the house of Pai in Ch'uan-chou,

And yet you still declare,

"My lips aren't even moistened".

Water from the edge of th bamboos

Flows out refreshing,

Breeze from the heart of the flowers

Passes by fragrant.

When Hsiang-t'an's clouds disperse,

The evening mountains appear;

When Pa-shu's snows vanish,

The spring waters flow.

The mandarin ducks I've embroidered

I give you leave to look at,

But the golden needle that made them

Do not pass on to men.

Waves as the Yu Gate have risen

And the fish become dragons,

Yet fools still scoop out

The embankment's dank water.

Evening near the riverside --

A scene for a painter.

Throwing on his straw raincoat,

The fisherman returns home.

The moon outside my window

Is usually the same moon,

But as soon as there are plum flowers

It becomes a different moon.

No need at all of hills and streams

For quiet meditation;

When the mind had been extinguished

Even fire is refreshing.

The monkeys, clasping their young to their breasts,

Return behind the blue peaks;

A bird, holding a flower in its beak,

Alight before the green grotto.

With his staff across his back,

He pays no heed to men;

Quickly entering the myriad peaks,

He goes upon his way.

I saw merely fallen petals

Blown away by the wind;

How could I know that the garden trees'

Green shadows are many?

Fearsome and solitary in mien,

He does not boast of himself;

But, dwelling gravely in his domain,

Decides who is snake, who is dragon.

Over the river country

Spring winds are not stirring,

From within the deep flowers

The partridges cry.

When your spirit is high,

Augment your spirit;

Where there is no style,

There is also some style.

Snowy herons alighting in a field --

Thousands of snowflakes!

Yellow nightingales perching in a tree --

A flower-decked bough.

The golden bracelet on her arm

Is too loose by an inch,

Yet on meeting one she merely says:

"No, I'm not in love".

Lotus leaves are round,

Rounder even than a mirror;

Water-chestnut horns are sharp,

Sharper even than a gimlet.

In the bottomless bamboo basket

I put the white moon;

In the bowl of mindlessness

I store the pure breeze.

He himself took the jar

And bought the village wine;

Now he dons a robe

And makes himself the host.

Bamboo shadows sweep the stairs,

Yet not a mote of dust is stirred;

Moonbeams pierce to the bottom of the pool,

Yet in the water not a trace remains.

8

Though gold-dust is precious,

In the eyes it obscures the vision.

Three thousand blows in the morning,

Eight hundred in the evening.

Lovely snowflakes,

They fall nowhere else!

To look for hair on the back of a tortoise

Or seek for horns on the head of a rabbit.

When the stone man nods his head,

The wooden pillar claps its hands.

To shave iron from the needle-point;

To hack flesh from a heron's leg.

When I drop the line down a thousand feet,

My objective lies in the depth of the pool.

When chickens are cold they roost in a tree;

When ducks are cold they dive into the water.

The true does not conceal the false;

The bent does not hide the straight.

To the intelligent man, one word;

To the fleet horse, one flick of the whip.

When will the fellow who plays with the dirt

Ever have done!

Laymen and holy men dwell together,

Dragons and snakes intermingle.

Officially, a needle is not permitted to pass;

Unofficially, carriages can get through.

The oyster holds a moonbeam in its mouth;

The rabbit cherishes a child in its womb.

Entering fire he is not burned;

Entering water he is not drowned.

In the morning he reaches India;

In the evening he returns to China.

A fish that can swallow a boat

Doesn't swim around is a valley stream.

Ch'ao-fu waters his ox;

Hsu Yu washes his ears.

I do not emulate the sages;

I alone am to be revered.

2x8

When the sword-disc flies,

Sun and moon darken;

When the jewel-staff strikes,

Heaven and earth pale.

In the blacksmith's shop

There are still piles of blunt iron;

At the good physician's gate

More and more sick men wait.

From the top of the solitary peak,

I gaze at the clouds;

Close by the old ferry landing,

I am splashed with mire.

On the first day of winter

I sell my quilt and buy an ox;

On the last day of winter

I sell my ox and buy a quilt.

To pursue the Great Roc

Into the tube of a lotus stem;

To put Mount Sumeru

Into the eye of a midge.

On the Ku-su Terrace

We do not speak of the spring and autumn;

In front of my face

How can you discuss the profoundly mysterious!

If you want to write such a poem,

You must first be capable of such a mind;

If you want to paint such a picture,

You must first be capable of grasping such a form.

The fishermen singing on the misty shore

All extol good fortune and honour;

The woodcutters chanting among the lofty trees

Together rejoice in the era of peace.

If you can understand,

You will return to your village and became a rustic;

If you cannot understand,

You sill starve on Shou-yang.

On the top of the solitary peak,

He whistles at the moon and sleeps in the clouds;

Within the vast ocean,

He overturns the waves and rouses the breakers.

Not to take what Heaven gives

Is to incur Heaven's calamity;

Not to act when the moment comes

Is to incur Heaven's misfortune.

Enwrapped in billows of white clouds,

I do not see the white clouds;

Absorbed in the sounds of flowing water,

I do not hear the flowing water.

When Yao's influence spread throughout the land,

The peasants sang their songs;

When Shun's radiance shone o'er his vast domain,

The fishermen drummed with their oars.

I take blindness as vision, darkness as hearing;

I take danger as safety, and prosperity as misfortune.

When I see smoke beyond the mountain, I know there's a fire;

When I see horns beyond the fence, I know there's an ox.

To pass through the dusky turmoil of the world

You must know the main road;

To dispense healing medicine

You must first inquire into the source of the illness.

When an ordinary man attains knowledge he is a sage;

When a sage attains understanding he is an ordinary man.

Though a cockatoo can talk,

It is just a bird;

Though an orang-outang can speak,

It is still just a beast.

But for the rule and the compass,

The square and the circle could not be determined;

But for the plumb-line,

The straight and the bent could not be rectified.

Above the budless branches,

The golden phoenix soars;

Around the shadowless tree,

The jade elephant circumambulates.

![]()

Zenrin Kusu

Kepes János fordítása Alan W. Watts angol verziójából

In: A zen útja, 1997

A Zenrin Kusu mintegy ötezer kétsoros verset [sic!] tartalmazó antológia,

amelyet Tojo Eicso (1429-1504) állított össze. Célja az volt, hogy olyan

verses forrást adjon a zen tanítványok kezébe, amelyből kifejező kétsorost

választhatnak egy-egy újonnan megfejtett koan témájához. Sok mester ilyen

verset vár el, mihelyt megszületett a megfelelő válasz a koanra. A kétsorosok

kínai források széles köréből - buddhista, taoista, klasszikus irodalomból,

népköltészetből stb. származnak.[25 vers]

A bajjal jó szerencse ér;

Egyezéssel ellenkezés.Alkonyatkor a hajnalt hirdeti

A kakas - éjfélkor a fénylő napot.Hidegben a pattogó láng köré telepszünk;

Hőségben patakpartra a bambuszligetben.Ragyogó nap süt ránk a zivatarban;

Hűs vizet hörpintünk a tűz ölén.Nem a naptól várja hevét a tűz,

Sem a holdtól hűvösségét a szél.Fákban ölt testi alakot a szél;

Hullámokban a hold energiája.A hajnal diafénye csak egy órát ragyog,

Mégis felér az óriásfenyővel,

Mely ezer évig állt.Ha virág hull le, még fáj elveszteni;

Ha gyom terem, még fáj, hogy nőni látod.Tavaszi táj, nincs benne se magas, se alacsony;

Virágzó ágak - egyik hosszú, másik rövid.Ami hosszú, az Buddha hosszú teste;

Ami rövid, az Buddha rövid teste.Kardként hasít, de nem hasít magába;

Lát, mint a szem, s nem látja önmagát.Nyugodtan ülni, nem tenni semmit,

Jön a tavasz, a fű kinő magától.A kék hegyek maguktól kék hegyek;

A fellegek maguktól fellegek.Nem kaphatod meg, ha gondolsz rá;

Nem kérheted, ha rá se gondolsz.Ha nem hiszel, nézd a szeptembert, az októbert!

Sárga levelek hullnak, belepnek hegyet, folyót.Ha találkoznak, egyre csak nevetnek:

Az az erdei pagony! Az a száraz avar!Semmi sem ér fel az öltözködéssel, evéssel.

Azon kívül sem Buddha nincs, sem pátriárkák.Hogy tud eredeti tudatról, természetről —

Épp ebben áll a zen súlyos baja!Erdőben jár, és a fűszál se rezzen;

Vízbe gázol, s nem ver hullámokat.Az élet úgy marad meg, ha elpusztítod:

S akkor köszönt először béke rád.

Egyetlen szó eget-földet helyére tesz;

Egyetlen kard egész világot elsimít.Ahogy pillangó száll az ültetett virágra,

Úgy mondja Bódhidharma: „Nem tudok”.A vadlúd képe nem szándékkal vetül rá;

A víz sem igyekszik, hogy befogadja.Vu-tai hegyen felhők - gőzölgő rizshalom;

Az ősi Buddha-csarnok előtt egy kutya az égre pisál.Elült a szél, a szirmok egyre hullnak;

Madár rikolt. Mélyül a hegyek csöndje.Repedt tükör már nem mutatja képed;

Lehullt szirom nem nő az ágra vissza.

A ZENRINKUSU GYŰJTEMÉNYBŐL

Fordította: Faludy György

In: Test és Lélek, 396-397. oldal

[Öt vers]

Fakul a fű a vézna fák alatt.

Lehullott a gyümölcsös levele,

de kertünk mégis egyre tágasabb,

mert több holdvilág fér bele.

Itt állunk a kilátó korlátjánál

szorosan egymás mellett, és szájtátva

nézzük a hegyláncot a messzeségben,

bár mindegyikünk más színűnek látja.

Érvelsz? Az érvelés nem magyarázat.

Ne másnak papolj: magaddal közöld,

hogy fejed felett nincs tető, sem lábad

alatt egyetlen talpalatnyi föld.

Nem kerüli el gondját semmi;

a mindenség okát kívánja

kifejteni s fejünkbe verni.

Ez vallásunk legfőbb hibája.

Mi az ész s az észnek a test?

Utitárs, sírbolt, szálloda?

S a lélek? Felhők közt keresd,

milyen a madár lábnyoma.

禪林句集 Zenrin-kushū

A Zen-erdő összegyűjtött mondásaiból

Fordította: Terebess Gábor

Négy írásjegyből álló kifejezések

啞子喫蜜

Asu mitsu o kissu.

Mézet kóstol a néma.

腦後一鎚

Nōgo ni ittsui.

Tarkóra mért pörölycsapás.

白日靑天

Hakujitsu seiten.

Ragyog a nap, kék az ég.

白日迷路

Hakujitsu michi ni mayou.

Eltéved verőfényben.

八寒八熱

Hakkan hachinetsu.

Nyolc jeges [pokol], nyolc tüzes [pokol].

不生不死

Fushō fushi.

Szülhetetlen, halhatatlan.

捋虎鬚也

Koshu o nazuru ya.

Húzgálja a tigris bajszát.

弋不射宿

Yoku suredomo netori o irazu.

Vadászat közben nem lőtt le pihenő madarakat.

A mester horgászott, de sohasem használt hálót. Sohasem lőtt rá megülő madárra.

Tőkei Ferenc fordítása

In: Konfuciusz: Lunyu 論語, Beszélgetések és mondások, VII, 26.

無位眞人

Mui i no shinnin.

Se rendű-rangú igaz ember. [= Cím és rang nélküli igaz ember.]

Vörös húskupacod belakja egy se-rendű-rangú igaz ember, aki folyton-folyvást ki-be jár az arcod nyílásain – szólt Lin-csi a csarnokba gyűlt szerzetesekhez. – Ki nem tett még tanúbizonyságot?

Egy szerzetes előrefurakodott, és azt kérdezte:

– Ki az a se-rendű-rangú igaz ember?

Lin-csi leszállt a székéből és vállon ragadta:

– Beszélj, bökd ki már!

A szerzetes próbált valamit mondani, de a mester ellökte magától:

– Egy rakás szar ez a se-rendű-rangú igaz ember! – mondta, és visszatért a szobájába.

龍頭蛇尾

Ryōtō dabi.

Sárkány a feje, kígyó a farka.

掩耳偸鈴

Mimi o ōte suzu o nusumu.

Befogja a fülét, harangot megy lopni.

間不容髮

Ma ni hatsu o irezu.

Egy hajszál se fér be közé.

勞而無功

Rō shite kō nashi.

Keményen dolgozik, mégsem ér el semmit.

渡驢渡馬

Ro o watashi, uma o watasu.

Átkel azon szamár is, ló is.

– Régóta hallom emlegetni a híres csaocsoui kőhidat – szólt egy vándorszerzetes Csao-csouhoz (778–897) –, de itt csak néhány cölöpöt meg pallót látok.

– Egy közönséges fahídtól meg se látod a csaocsoui kőhidat – mondta Csao-csou.

– Mi volna az a csaocsoui kőhíd?

– Átmegy azon a szamár is, a ló is!

Öt írásjegyből álló kifejezések

好事不如無

Kōzu mo naki ni wa shikazu.

Holmi jónál jobb a semmi.

擔水河頭賣

Mizu o ninatte katō ni uru.

Folyóparton árulja a kimert vizet.

按牛頭喫草

Gozu o anjite kusa o kisseshimu.

Lenyomja az ökör fejét, hogy legeljen.

吾無隱乎爾

Ware nanji ni kakusu koto nashi.

Nincs titkom előttetek.

Semmit sem titkolok előletek.

Tőkei Ferenc fordítása

In: Konfuciusz: Lunyu 論語, Beszélgetések és mondások, VII, 23.

鑊湯無冷處

Kakutō ni reisho nashi.

Egy fortyogó üstben nincs hűvös zug.

泥裏洗土塊

Deiri ni dokai o arau.

Iszapban mossa ki a sárfoltot.

巧匠不留跡

Kōshō ato o todomezu.

Az ügyes kézműves nem hagy nyomot maga után.

貧兒思舊債

Hinji kyūsai o omou.

A koldust régi tartozása emészti.

庭前柏樹子

Teizen no hakujushi.

Ciprusfa az udvaron.

– Miért jött ide nyugatról Bódhidharma? – kérdezte egy szerzetes.

– Ciprusfa az udvaron – felelte Csao-csou.

Hat írásjegyből álló kifejezések

好語不可説盡

Kōgo wa tokitsukusu bekarazu.

Egy jó beszélgetésnek nem kell mindent megmagyaráznia.

臂膊不向外曲

Hihaku soto ni mukatte magarazu.

A kar nem hajlik kifelé.

一箪食一瓢飲

Ittan no shi, ippyō no in.

Egyetlen tál étel, egyetlen tökhéj-kupa ital.

Egy bambuszkosárnyi ételen és egy tökhéjnyi italon, nyomorúságos sátorban élt.

Tőkei Ferenc fordítása

In: Konfuciusz: Lunyu 論語, Beszélgetések és mondások, VI, 9.

未知生焉知死

Imada shō o shirazunba izukunzo shi o shiran.

Ha soha nem értetted az életet, hogyan értenéd meg a halált?

Aki még az életet sem ismeri, hogyan ismerhetné meg a halált?

Tőkei Ferenc fordítása

In: Konfuciusz: Lunyu 論語, Beszélgetések és mondások, XI, 11.

無友不如己者

Onore ni shikazaru mono o tomo to suru koto nakare.

Ne barátkozz velük, akik nem magadfélék.

A legtöbbre a hűséget és szavahihetőséget kell becsülni, nem szabad olyanokkal barátkozni, akik nem érnek annyit, mint mi, és ha hibázunk, nem szabad félni attól, hogy kijavítsuk.

Tőkei Ferenc fordítása

In: Konfuciusz: Lunyu 論語, Beszélgetések és mondások, I, 8.

君子周而不比

Kunshi wa shū shite hi sezu.

A felsőbbrendű ember mindenkit befogad, és nem hasonlítgat.

A mester mondotta: „A nemes ember (junzi 君子) egyetemes (zhou 周)

és nem részrehajló; a kis ember (xiaoren 小人) részrehajló és nem

egyetemes.”Tőkei Ferenc fordítása

In: Konfuciusz: Lunyu 論語, Beszélgetések és mondások, II, 14.

聞名不如見面

Na o kiku yori omote o min ni wa shikazu.

Jobb látni az arcot, mint hallani a nevet.

好兒不使爺錢

Kōji yasen o tsukawazu.

A jó fiú nem költi apja pénzét.

無孔笛最難吹

Mukuteki mottomo fukigatashi.

A lyuk nélküli fuvolát a legnehezebb megfújni.

Vö.

鐵笛倒吹

Tetteki tōsui

Visszáján-fújt vasfuvola

跨瞎驢追猛虎

Katsuro ni matagatte, mōko o ou.

Vak szamár hátán vágtat a vad tigris után.

Hét írásjegyből álló kifejezések

再來不直半文錢

Sairai hanmonsen ni atarazu.

A második próbálkozás feleannyit sem ér.

朝聞道夕死可也

Ashita ni michi o kiite yūbe ni shi sutomo ka nari.

Ha reggel hallom a Taót, este meghalhatok.

A mester mondotta: „Aki reggel meghallgatta az igazságot (dao 道), az este akár meg is halhat.”

Tőkei Ferenc fordítása

In: Konfuciusz: Lunyu 論語, Beszélgetések és mondások, IV, 8.*

A Mester mondotta:

Aki reggel felismeri a Helyes Utat,

Az mit se bánja, ha halált hoz az alkonyat.Őri Sándor fordítása

摽有梅其實七兮

Ochite ume ari sono mi nanatsu.

Hullt a szilva, hét szem volt.

Hét szem szilvát

hullat a fája

Távoli férfit

asszonya várja.Rab Zsuzsa fordítása

In: Si King - Dalok könyve, 20.

Nyolc írásjegyből álló kifejezések

水不洗水

金不博金

Mizu mizu o arawazu, kin kin ni kaezu.

Vizet vízzel nem mosdatunk,

Aranyt aranyra nem váltunk.

水到渠成

風行草偃

Mizu itatte kyo nari, kaze yuite kusa fu su.

Merre vizek folynak, medreket vájnak,

Merre szelek fújnak, fűszálak hajolnak.

水結成冰

冰釋成水

Mizu musunde kōri to nari, kōri tokete mizu to naru.

Jéggé fagy a víz,

vízzé olvad a jég.

閉門造車

出戸合轍

Mon o tojite kuruma o tsukuri, to o idete wadachi ni gassu.

Zárt kapuk mögött szekeret gyárt;

kínt keréknyomba illeszti.

箭既離弦

無返回勢

Ya sude ni yumi o hanarete, henkai no ikioi nashi.

A kilőtt nyíl nem jön vissza.

良醫之門

病者愈多

Ryōi no mon byōsha hanahada ōshi.

A jó orvos kapujánál rengeteg a beteg.

呑舟魚不

遊數仭谷

Fune o nomu uo wa sūjin no tani ni asobazu.

A hal, mely képes lenyelni egy hajót,

Nem úszkál sekély hegyi patakban.

好雪片片

不落別處

Kōsetsu hen-pen bessho ni ochizu.

Csodás egy hóhullás!

Épp a helyére hull mindegyik pehely.

Jao-san Vej-jen mester [745-828] elbúcsúztatta Pang Jünt [740-808], és tíz tanítványát küldte, hogy kísérjék a kapuig.

Ott Pang Jün megállt a sűrű hóesésben:

– Csodás egy hóhullás! – mondta. – Épp a helyére hull mindegyik pehely.

Egy Csüan nevű tanítvány megkérdezte:

– Mutasd, hová hullanak!

Pang Jün az arcába csapott.

雞寒上樹

鴨寒下水

Niwatori samū shite ki ni nobori, kamo samū shite mizu ni kudaru.

Ha a tyúkok fáznak, fára szállnak;

Ha a kacsák fáznak, vízbe buknak.

– Mi a különbség a csan pátriárkák és Buddha tanítása között? – kérdezte egy szerzetes.

– A tyúkok, ha fáznak, felülnek a fára; a kacsák, ha fáznak, lebuknak a vízbe – felelte Pa-ling Hao-csien, [10. sz.].

電飛雷走

山崩石裂

Den tobi rai hashiri yama kuzure ishi saku.

Villámcsapás, mennydörgés, hegyomlás, kőhasadás.

爭名者朝

爭利者市

Na o arasou mono wa chō shi, ri o arasou mono wa shi su.

Az udvarban nevet szereznek, a piacon meg hasznot.

飯裡有砂

泥中有棘

Hanri ni isago ari, deichū ni ubara ari.

Homok a rizsen, tövis a sárban.

不入虎穴

爭得虎兒

Koketsu ni irazunba ikadeka koji o en.

Ha nem mész be a tigris barlangjába,

hogy kapod el a tigris kölykét?

鵠不浴白

鴉不染黑

Koku wa yoku sezu shite shiroku,

a wa somezu shite kuroshi.

A hattyú fürdés nélkül is fehér,

a holló festés nélkül is fekete.

„Ha töreket szórsz, s por megy a

szemedbe, a világ mind a négy sarka tótágast áll előtted.

Ha szúnyogok és bögölylegyek csipdesik bőrödet, egész

éjjel se tudsz elszenderedni. Az emberség meg az igazságosság

ugyanígy gyötri szívünket lankadatlan, s a legnagyobb

zűrzavart támasztja bennünk. Ne térj el az Ég alatti

világ romlatlan egyszerűségétől, úgy mozdulj, szabadon,

akár a szél, s valódat egybefogva szilárdan állj! Ugyan mire

való e buzgólkodás, nagydobot püfölve indulni az elveszett

gyermek felkutatására?

A hóludak nem mosdanak naponta, hogy fehérek legyenek,

s a varjú sem mázolja magát korommal, mégis fekete a

tolla. Fehér és fekete színük romlatlan egyszerűségéről hasztalan

vitáznál. A hírnév és dicsőség érveivel felesleges foglalkozni.

Mikor a források kiszáradnak, a halak a földön hevernek,

szájukból adnak egymásnak nedvességet, és síkos

testükkel kenik össze egymást. De mennyivel jobb volna,

ha önfeledten úszkálhatnának a folyókban és tavakban!"

Dobos László fordítása

In: Csuang-ce: A virágzó délvidék igaz könyve I - XVI.,

XIV. Az Égi körforgás, pp. 117-118.

咬人獅子

不露爪牙

Hito o kamu shishi sōge o arawasazu.

Egy emberevő oroszlán nem fitogtatja fogát és karmát.

入火不燒

入水不溺

Hi ni itte mo yakezu, mizu ni itte mo oborezu.

Tűzben nem ég meg, vízben nem fúl meg.

王敕已行

諸侯避道

Ani shuku ya ni sezaranya, omowaku michi ni tsuyu ōkaran.

Miért nem mentem ki kora reggel?

Gondoltam, harmattól nedves az út.

Csupa harmat minden út meg minden hajlat,

hajnal és éj kéz a kézben együtt ballag,

bizony, csupa harmat az út, csupa harmat.Szabó Magda fordítása

In: Si King - Dalok könyve, 17.

伐柯伐柯

其則不遠

Ka o kiri, ka o kiru, sono nori tōkarazu.

Nyélfaragás, nyélfaragás,

itt a mintám, fejsze nyele.

Fejszenyélre, fejszenyélre

vágó-fejsze nyele minta.

Mikor veled találkozom,

ott a teli kosár, kanna.Weöres Sándor fordítása

In: Si King - Dalok könyve, 158.

鳶飛戻天

魚躍于淵

Tobi tonde ten ni itari, uo fuchi ni odoru.

Madár repül fel az égbe,

Halak buknak le a mélybe.

Sólyommadár égig hussan.

Száll le hal a mély tengerben.

Mulat az urunk vidáman.

Valójában nem is ember.Jánosy István fordítása

In: Si King - Dalok könyve, 239.

野有死麕

白茅包之

No ni shikin ari, hakubō kore o tsutsumu.

Mezőn elhullott őzgida,

fehér gyász-sás beborítja.

Halott szarvas rétre rogyva,

a fehér fű beborítja.

Leány gondol a tavaszra,

derék vitéz várja-hívja.Weöres Sándor fordítása

In: Si King - Dalok könyve, 23.

我有嘉賓

鼓瑟吹笙

Ware ni kahin ari, koto o hiki fue o fuku.

Tekintetes vendég érkezik ma,

Hadd szóljon a hárfa, flóta.

Dobog, bőg a szarvas-falka,

erdőben a rügyet falja.

Nemes vendég jött házamba,

húr pengjen, síp zendüljön ma,

síp-ajk zümmögjön-zenegjen,

ajándékkal kosár teljen,

nemes vendég, becsül engem,

minden lépte csupa illem.Weöres Sándor fordítása

In: Si King - Dalok könyve, 161.

爲學日益

爲道日損

Gaku o osamuru mono wa hi ni mashi,

Michi o osamuru mono wa hi ni sonsu.

Aki tanul, napról napra többet nyer;

aki az Utat járja, napról napra csak fogy.

A tanuló gyarapszik naponta;

az út-on járó csökken naponta.

Csökkenés, tovább-csökkenés:

eredménye a nem-cselekvés.

Mindent végbevisz a nem-cselekvés.

A világot tétlen tartja kézben.

Aki tevékeny,

a világot nem tartja kézben.Weöres Sándor fordítása

In: Lao-Ce: Az Út és Erény könyve, 48.

逢佛殺佛

逢祖殺祖

Butsu ni ōte wa butsu o koroshi, so ni ōte wa so o korosu.

Ha egy buddhával találkoztok, öljétek meg azt a buddhát!

Ha egy pátriárkával találkoztok, öljétek meg azt a pátriárkát!

– Hívek, akarjátok tisztán, a Törvénynek megfelelően

látni a dolgokat? Csak attól őrizkedjetek, hogy mások tév-

útra vigyenek benneteket. Mindent, ami utatokba akad,

akár kinn, akar bennetek, öljétek meg! Ha egy buddhával

találkoztok, öljétek meg azt a buddhát! Ha egy pátriárká-

val találkoztok, öljétek meg azt a pátriárkát! Ha egy ar-

hattal találkoztok, öljétek meg az arhatot! Ha atyátokkal

és anyátokkal találkoztok, öljétek meg atyátokat és anyá-

tokat! Ha rokonaitokkal találkoztok, öljétek meg a roko-

nokat! Ez az egyetlen módja megszabadulásotoknak, a

dolgok rabságából való megszökésteknek, ez maga a me-

nekvés, ez maga a függetlenség.Miklós Pál fordítása

In: Lin-csi Lu – Feljegyzések Lin-csiről, 20.

金屑雖貴

落眼成翳

Kinsetsu tattoshi to iedomo, manako ni ochite ei to naru.

Hiába drága az aranypor,

a szemben csak gyulladást okoz.

Vang kormányzó [Vang Sao-ji, ?-866] meglátogatta a mestert. Amikor elsétáltak a szerzetesek csarnoka előtt, megkérdezte:

– Hát a szútrákat tanulmányozzák-e a szerzetesek?

– Azt ugyan nem – felelt Lin-csi Ji-hszüan [?–866].

– Tán az elmélkedést gyakorolják?

– Azt sem.

– Akkor mivel foglalkoznak?

– Azzal, hogy buddhák és pátriárkák legyenek!

– Hiába drága az aranypor, a szemben csak gyulladást okoz – mondta a kormányzó.

– És én még közönséges embernek hittelek! – kiáltott fel Lin-csi.

Kilenc írásjegyből álló kifejezések

溺者入水拯者亦入水

Oboruru mono mizu ni iri, sukuu mono mata mizu ni iru.

Fuldokló a vízben, kimentője ugyancsak.

一生二

二生三

三生萬物

Ichi ni o shōji,

Ni san o shōji,

San banbutsu o shōzu.

Az egy szülte a kettőt,

a kettő a hármat,

a három valamennyi létezőt.

Az ÚT szüli az egyet,

az egy a kettőt,

a kettő a hármat,

a három a létezőket.

A létezők hátán a jin,

keblén a jang;

a lélekerő adja

összhangjukat.Kulcsár F. Imre fordítása

In: Lao-ce: Tao te king - Az Út és az Erény könyve, 42.

一箇打着一箇打不着

Ikko wa tajaku, ikko wa tafujaku.

Az egyik nyert, a másik vesztett.

Egyik nap pirkadatkor Fa-jen Ven-ji (885-958) a bambuszrolóra mutatott. Mindjárt két szerzetes sietett oda, hogy felgöngyölje.

– Az egyik nyert, a másik vesztett – mondta Fa-jen.

兄弟鬩于墻外禦其侮

Keitei kaki ni semegedomo, soto sono anadori o fusegu.

[A testvérek]

Házon belül összekapnak,

házon kívül összefognak.

Póli-madár fut az érhez,

testvér, bajban, testvéréhez,

míg mindannyi jóbarátja

óvatos, bár vele-érez.Házon belül összekapnak,

házon kívül összefognak,

míg az érző jóbarátok

csak tétlenül sopánkodnak.Weöres Sándor fordítása

In: Si King - Dalok könyve, 164.

Tíz írásjegyből álló kifejezések

赦有罪寵女

斬無罪卑女

Yūzai no chōjo o yurushi,

Muzai no hijo o kiru.

Megkegyelmez a gyönyörű, de bűnös lánynak,

és lefejezi a csúnya, de ártatlan leányt.

梅痩占春少

庭寛得月多

Ume yasete haru o shimeru koto sukunaku,

Niwa hirō shite tsuki o uru koto ōshi.

A kiszáradt szilvafák alig őrzik a tavaszt,

De a kert megnyílik, befogadja a holfényt.

Fakul a fű a vézna fák alatt.

Lehullott a gyümölcsös levele,

de kertünk mégis egyre tágasabb,

mert több holdvilág fér bele.Zenrin kusú, Faludy György fordítása

鸚鵡叫煎茶

與茶元不識

Ōmu sencha to sakebu,

Cha o atauredomo moto shirazu.

A papagáj teát kér,

De ha teával kínálod, nem tudja mire vélni.

爲己鎖者多

爲他鎖者少

Onore ga tame ni tozasu mono wa ōku,

Ta no tame ni tozasu mono wa sukunashi.

Sokan vannak, akik lekötözik magukat;

Néhányan vannak, akik lekötöznek másokat.

風定花猶落

鳥鳴山更幽

Kaze shizumatte hana nao ochi,

Tori naite yama sara ni yū nari.

Szélcsend, a virágok még hullanak;

Madárdal, a hegy még csöndesebb.

Zenrin kusú, Kepes János fordítása Alan W. Watts angol verziójából

In: A zen útja, 1997:Elült a szél, a szirmok egyre hullnak;

Madár rikolt. Mélyül a hegyek csöndje.

無風荷葉動

決定有魚行

Kaze naki ni kayō ugoku.

Ketsujō uo no yuku koto aran.

Szélcsendben reszketnek a lótuszszirmok;

Biztos hal úszik el mellettük.

瓜田不納履

梨下不整冠

Kaden ni ri o osamezu,

Rika ni kanmuri o tadasazu.

Ha dinnyeföldön mész keresztül, ne kösd meg a bocskorod.

Az almáskertben ne igazgasd a kalapod.

窮鼠反咬猫

闘雀不畏人

Kyūso kaette neko o kami,

Tōjaku hito o osorezu.

A sarokba szorított patkány megfordul és belemar a macskába,

A viaskodó verebek nem félnek az embertől.

窮鳥入懐則

弋者亦救之

Kyūchō futokoro ni ireba,

Yokusha mo mata kore sukuu.

Ha kétségbeesett madár menekül a keblére,

A vadász is megkönyörül rajta.

久旱逢初雨

他郷遇舊知

Kyūkan shou ni ai,

Takyō kyūchi ni au.

Hosszú aszály után köszöntjük az első esőt.

Egy másik faluban régi barátomba botlok.

草作靑靑色

春風任短長

Kusa wa sei-seitaru iro o nashi,

Shunpū tanchō ni makasu.

A fű zöld-zöld színű;

Legyen hosszú vagy rövid, a tavaszi szél nem bánja.

狗吠乞兒後

牛耕農夫前

Ku wa kotsuji no ato ni hoe,

Ushi wa nōfu no mae ni kō su.

A kutya a koldus után ugat,

Az ökör a paraszt előtt szánt.

欄干雖共倚

山色看不同

Rankan tomo ni yoru to iedomo,

Sanshoku miru koto onajikarazu.

Bár ugyanarra a korlátra támaszkodunk,

Nem látjuk ugyanúgy a hegyek színeit.

Itt állunk a kilátó korlátjánál

szorosan egymás mellett, és szájtátva

nézzük a hegyláncot a messzeségben,

bár mindegyikünk más színűnek látja.Zenrin kusú, Faludy György fordítása

視之而弗見

聽之而弗聞

Kore o miredomo miezu,

Kore o kikedomo kikoezu

Bár nézem, nem látom;

Bár hallgatom, nem hallom.

Ránézek, de nem látom,

ezért neve: nem látható.

Hallgatom, de nem hallom,

ezért neve: nem hallható.

Megragadnám, de meg nem foghatom,

ezért neve: a legparányibb.

E három titok

egységbe olvad.

Felszíne sem világos,

alapja sem homályos,

végtelen, névtelen,

visszavezet a nemlétbe szüntelen.

Neve: formátlan forma,

tárgy-nélküli kép,

neve: a sötét.Weöres Sándor fordítása

In: Lao-Ce: Az Út és Erény könyve, 14.

詩向會人吟

酒逢知己飮

Shi wa kaijin ni mukatte ginji,

Sake wa chiki ni ōte nomu.

Dalom azoknak éneklem, akik megértenek;

Borom azokkal iszom, akik jól ismernek.

Vö.

József Attila: (Csak az olvassa...)

Csak az olvassa versemet,

ki ismer engem és szeret,

mivel a semmiben hajóz

s hogy mi lesz, tudja, mint a jós,

mert álmaiban megjelent

emberi formában a csend

s szivében néha elidőz

a tigris meg a szelid őz.

1937. jún. eleje

宿昔靑雲志

蹉跎白髪年

Shukushaku seiun no kokorozashi,

Satatari hakuhatsu no toshi.

Régen olyan magasra törtem, mint a kék ég,

Most pedig nyűtt, fehér hajú öregember vagyok.

出身猶可易

脱體道應難

Shusshin wa nao yasukarubeshi,

Dattai ni iu koto wa masa ni katakarubeshi.

Könnyű megszabadulni az éntől,

De a szabadulás után nehéz megszólalni.

聖人無恒心

以民心爲心

Seijin kōshin nashi,

Minshin o motte shin to nasu.

A bölcsnek nincs saját szíve.

A többiek szívét teszi sajátjává.

A bölcsnek nincs önnön szíve.

Szíve a nép valahány szíve.

Weöres Sándor fordítása

In: Lao-Ce: Az Út és Erény könyve, 49.

有錢千里通

無錢隔壁聾

Zeni areba senri mo tsūji,

Zeni nakereba kabe o hedatete rō su.

Ha van pénzed, cseveghetsz a világgal;

Ha nincs pénzed, szomszédod süket.

善惡如浮雲

起滅倶無處

Zen’aku fūun no gotoku,

Kimetsu tomo ni tokoro nashi.

A jó és a rossz olyanok, mint az úszó felhők,

sehol sem keletkeznek, sehol sem oszlanak el.

僧投寺裡宿

賊打不防家

Sō wa jiri ni tōjite shuku shi,

Zoku wa fubō no ie o ta su.

A szerzetes egy templomba tart, hogy megszálljon éjszakára,

A tolvaj betör egy őrizetlen házba.

大隱隱朝市

小隱隱山林

Daiin wa chōshi ni kakure,

Shōin wa sanrin ni kakuru.

Egy nagy remete az udvarban és a piacon rejtőzik,

Egy kis remete a hegyekben és az erdőkben rejtőzik.

大海任魚躍

長空任鳥飛

Daikai wa uo no odoru ni makase,

Chōkū wa tori no tobu ni makasu.

A nagy óceán hagyja a halakat ugrálni,

A hatalmas ég hagyja a madarakat repdesni.

只改舊時相

不改舊時人

Tada kyūji no sō o aratamete,

Kyūji no hito o aratamezu.

Csak korábbi külsejét változtatta meg,

De korábbi önmagát nem.

傭他癡聖人

擔雪共塡井

Ta no chiseijin o yatōte,

Yuki o ninōte tomo ni sei o uzumu.

Felbérel egy másik bolondot,

és együtt hordják a havat betömni egy kutat.

長者長法身

短者短法身

Chōja wa chōhosshin,

Tanja wa tanhosshin.

Egy hosszú dolog - hosszú Buddha-test,

Egy rövid dolog - rövid Buddha-test.

塵埋床下履

風動架頭巾

Chiri wa shōka no ri o ume,

Kaze wa katō no kin o ugokasu.

Por temeti el a cipőket az ágy alatt,

Szél borzolja a kendőt a fogason.

時與道人偶

或隨樵者行

Toki ni dōjin to gū shi,

Aruiwa shōsha ni shitagatte yuku.

Néha az Út emberével tartunk,

néha egy favágót követünk.

日日是好日

風來樹點頭

Nichi nichi kore kōnichi,

Kaze kitatte ju tentō su.

Minden nap jó nap.

Amikor fúj a szél, a fa meghajol.

愛之欲其生

惡之欲其死

Kore o ai shite wa sono sei o hosshi,

Kore o nikunde wa sono shi o hossu.

Ha szereted, élve akarod;

Ha gyűlölöd, halva akarod.

Akit szeretünk, annak azt kívánni, hogy éljen; akit gyűlölünk, annak azt kívánni, hogy haljon meg; vagy akár egyszer életet, másszor meg halált kívánni valakinek; mindez hamis dolog (mert az élet és halál az Égtől függ).

Tőkei Ferenc fordítása

In: Konfuciusz: Lunyu 論語, Beszélgetések és mondások, XII, 10.

謂火不燒口

謂水不溺身

Hi to iu mo kuchi o yakazu,

Mizu to iu mo mi o oborasazu.

Hiába mondod, hogy „tűz”, nem égeted meg a szádat;

Hiába mondod, hogy „víz”, nem fojtod meg a tested.

– Bár tüzet mondunk – mondta Jün-men Ven-jen (864-949) –, mégse égetjük meg a szánkat.

歩歩行舌頭

歩歩歸話頭

Ho-ho zettō ni yuki,

Ho-ho watō ni kaeru.

Minden előrelépéssel – a te kōanod.

Minden visszalépéssel – a te kōanod.

路逢逹道人

不將語默對

Michi ni tatsudō no hito ni awaba,

Gomoku o motte taisezare.

Ha bölcs emberrel találkozol az úton,

Hogy köszöntöd, ha se nem szólhatsz, se nem hallgathatsz.

Vu-cu Fa-jen (1024-1104) egyszer azt kérdezte:

– Ha bölcs emberrel találkozol az úton, se nem szólhatsz, se nem hallgathatsz. Hogy köszöntöd?

Vu-cu Fa-jen mondott egy példát:

– Olyan, mintha bivaly ballagna el az ablakrács előtt. Áthalad a feje, a szarva, mind a négy patája – de a farka miért nem jut át soha?

掬水月在手

弄花香滿衣

Mizu o kiku sureba, tsuki te ni ari,

Hana o rō sureba, kō e ni mitsu.

Meríts vizet, és markodban a hold virul,

Szedj virágot, és köntösöd megillatosul.

削足而適履

殺頭而便冠

Ashi o kezutte ri ni kanai,

Atama o soide kanmuri ni ben ni su.

Lábát vágja cipőjéhez,

fejét nyesi kalapjához.

庵中閑打坐

白雲起峯頂

Anchū shizuka ni taza sureba,

Hakuun hōchō ni okoru.

Ahogy csendben a kunyhómban üldögélek,

Fehér felhők hegycsúcsokon gomolyganak.

環家萬里夢

爲客五更愁

Ie ni kaeru, banri no yume,

Kyaku to naru, goko no urei.

Hazatérés! — tízezer mérföldön át erről álmodtam,

Útrakelés! — hajnali négykor az ágyban aggódom.

石壓笋斜出

岸懸花倒生

Ishi oshite takanna naname ni ide,

Kishi ni kakatte hana sakashima ni shōzu.

Kő alól ferdén nő a bambusz.

Szirtről lefelé nő a virág.

水流元入海

月落不離天

Mizu nagarete moto umi ni iri,

Tsuki ochite ten o hanarezu.

A víz folyik, de mindig a tengerbe ömlik,

A hold lemegy, de soha nem hagyja el az eget.

雪續溪橋斷

煙彰山舎藏

Yuki wa keikyō no taetaru o tsugi,

Kemuri wa sansha no kakururu o arawasu.

Hó fedi a törött híd rését,

Füst fedi fel a hegyi kunyhó rejtekét.

羅籠不肯住

呼喚不回頭

Rarō suredomo aete todomarazu,

Kokan suredomo kōbe o megurasazu.

Zárd ketrecbe, és nem marad a helyén,

Hívd vissza, és nem fordítja meg a fejét.

覓火和烟得

擔泉帯月帰

Hi o motomete wa kemuri ni majiete e,

Izumi o ninatte wa tsuki o obite kaeru.

Tüzet kutatsz, a füstjével leled meg;

Forrásvizet cipelsz, a holddal viszed haza.

十年帰不得

忘却来時道

Jūnen kaeru koto o ezumba,

Raiji no michi o bōkyaku su.

Tíz évig vissza nem térhettem;

Mostanra elfelejtettem, melyik úton jöttem.

兀然無事坐

春来草自生

Gotsunen to shite buji ni shite za sureba,

Shunrai kusa onozukara shōzu.

Nyugodtan ülsz, teszed a semmit;

Ha eljő a tavasz, kizöldül a fű magától.

Zenrin kusú, Kepes János fordítása Alan W. Watts angol verziójából.

In: A zen útja, 1997:Nyugodtan ülni, nem tenni semmit,

Jön a tavasz, a fű kinő magától.

入林不動草

入水不立波

Hayashi ni itte kusa o ogokasazu,

Mizu ni itte nami o tatezu.

Bemegy az erdőbe, de fűszálat sem zavar;

Bemegy a vízbe, de hullámot sem kavar.

Kepes János fordítása Alan W. Watts angol verziójából.

In: A zen útja, 1997:Erdőben jár, és a fűszál se rezzen;

Vízbe gázol, s nem ver hullámokat.

破鏡不重照

落花難上枝

Hakyō kasanete terasazu,

Rakka eda ni noborigatashi.

Az összetört tükör nem tükröz újra;

A hullott virág nem száll az ágra vissza.

Zenrin kusú, Kepes János fordítása Alan W. Watts angol verziójából.

In: A zen útja, 1997:Repedt tükör már nem mutatja képed;

Lehullt szirom nem nő az ágra vissza.

世尊不説説

迦葉不聞聞

Seson fusetsu no setsu,

Kashő fumon no mon.

Buddha hallgatott, mégis mindent elmagyarázott;

Kasjapa semmit nem hallott, mégis mindent megértett.

Sákjamuni Buddha tanítóbeszéd helyett egykor a Keselyű-bércen felmutatott egy szál virágot tanítványainak. Mindegyikük elnémult, de Mahákasjapa el is mosolyodott. Buddha így szólt:

– Bírom az igaz törvény szemefényét, a nirvána felfoghatatlan értelmét, a forma nélküli forma páratlan tanát. Nem fejezik ki szavak, a tanításon kívül adatik át. Most Mahákasjapára hagyom.

木雞鳴子夜

芻狗吠天明

Mokkei shiya ni naki,

Sūku tenmei ni hoyu.

A fából faragott kakas éjfélkor kukorékol;

A szalmakutya virradatkor csahol.

不知何處寺

風送鐘聲來

Shirazu izure no tokoro no tera zo,

Kaze shōsei o okuri kitaru.

Nem tudom, merre van az a templom,

De harangja hangját hozza a szél.

春來遊寺客

花落閉門僧

Shunrai yūji no kyaku,

Hana ochite mon o tozuru no sō.

Tavasszal sokan látogatják a templomot;

Virághulláskor a szerzetes becsukja a kaput.

牛飲水成乳

蛇飲水成毒

Ushi no nomu mizu wa chichi to nari,

Ja no nomu mizu wa doku to naru.

A tehén itta vízből tej lesz;

A kígyó itta vízből méreg.

泣露千般草

吟風一葉松

Tsuyu ni naku sempan no kusa,

Kaze ni ginzu ichiyō no matsu.

Ezer fűszál harmatkönnyet hullajt;

Árva fenyőfa sóhajt a szélben.

良匠無棄材

明君無棄士

Ryōshō ni wa sutsuru zai naku,

Meikun ni wa sutsuru samurai nashi.

A jó mesterembernek nincs kidobandó fája,

a megvilágosodott uralkodónak nincs pazarolható embere.

裂開也在我

揑聚也在我

Rekkai mo mata ware ni ari,

Netsuju mo mata ware ni ari.

A rombolás – bennem van.

Az építés – szintén bennem van.

Tizenegy írásjegyből álló kifejezések

道得三十棒

道不得三十棒

Iiurumo sanjūbō,

Iiezarumo sanjūbō.

Ha szólsz – harminc botütés,

Ha nem szólsz – harminc botütés.

Tö-san [Hszüan-csien, 780-865] kijelentette a szerzetesek csarnokában:

– Ha szóltok, leverek rajtatok harminc botütést, ha nem szóltok, akkor is leverek rajtatok harminc botütést.

好一釜羮

被兩顆鼠糞汚卻

Kōippu no atsumono,

Ryōka no sofun ni okyaku seraru.

Egy fazéknyi legjobb pörköltem,

Két adagnyi patkányürülékkel bemocskolva!

Ez Hakuin jakugo-ja „A forma maga üresség, az üresség maga forma” kifejezésre a Dokugo shingyō-ban (Waddell 1996, 31).

鐸以聲自毀

膏燭以明自鑠

Taku wa sei o motte mizukara kobotare,

Kōshoku mei o motte mizukara torakasu.

Hogy hangot adjon, a harang belereped;

Hogy fényt adjon, a gyertya elégeti magát.

Tizenkét írásjegyből álló kifejezések

寒時寒殺闍梨

熱時熱殺闍梨

Kanji wa jari o kansatsu shi,

Netsuji wa jari o nessatsu su.

A hideg hideggel öl,

A meleg meleggel öl.

士爲知己者死

女爲愛己者容

Shi wa onore o shiru mono no tame ni shishi,

Nyo wa onore o ai suru mono no tame ni katachizukuru.

A harcos azért hal meg, aki ismeri őt,

Az asszony annak öltözik, aki szereti őt.

以德勝人者昌

以力勝人者亡

Toku o motte hito ni masaru mono wa sakae,

Chikara o motte hito ni masaru mono wa horobu.

Akik erénnyel győznek le másokat, azok boldogulnak;

akik erőszakkal győznek le másokat, azok elpusztulnak.

„Darwin A fajok eredete című munkája szerint nem a legokosabb fajok, és nem is a legerősebbek maradnak életben, hanem azok, amelyek a legjobban képesek alkalmazkodni, amelyek a legfogékonyabbak a környezetükben végbemenő változásokra.” Charles Darwin: The Origin of Species (1859)

彼采艾兮

一日不見

如三歳兮

Fekete ürmöt szed a babám.

Csak egy röpke nap, míg nem látom,

mintha évből telt volna három.

Ott szedek üröm-levelet!

Ha csak egy nap nem látom őt,

három nagy évnél nehezebb!Illyés Gyula fordítása

In: Si King - Dalok könyve, 72.

上無片瓦蓋頭

下無寸土立足

Kami henga no kōbe o ōu naku,

Shimo sundo no ashi o rissuru nashi.

Feje fölött nincs egy cserépnyi födél,

Lába alatt nincs egy talpalatnyi föld.

Érvelsz? Az érvelés nem magyarázat.

Ne másnak papolj: magaddal közöld,

hogy fejed felett nincs tető, sem lábad

alatt egyetlen talpalatnyi föld.Zenrin kusú, Faludy György fordítása

逐鹿者不見山

攫金者不見人

Shika o ou mono wa yama o mizu,

Kin o tsukamu mono wa hito o mizu.

A szarvasvadász nem látja a hegyeket;

A fösvény nem látja az embereket.

爭如著衣喫飯

此外更無佛祖

Ikadeka jakue kippan ni shikan,

Kono hoka sara ni busso nashi.

Mivel vetekszik csupán öltözni és étkezni?

Kívülük nincsenek se buddhák, se ősök.

Vö.

Zenrin kusú, Kepes János fordítása Alan W. Watts angol verziójából.

In: A zen útja, 1997:Semmi sem ér fel az öltözködéssel, evéssel.

Azon kívül sem Buddha nincs, sem pátriárkák.*

„Ah, kínos élet: reggel, estve.

Öltözni és vetkezni kell!”Arany János: Híd-avatás (1877)

一人順水張帆

一人逆風把梶

Ichinin wa junsui ni ho o hari,

Ichinin wa gyakufū ni kaji o toru.

Az egyik a sodrással együtt vitorlázik,

a másik a szél ellen tartja a kormányt.

一人跨三脚驢

一人騎三角虎

Ichinin wa sankyaku no ro ni matagari,

Ichinin wa sankaku no tora ni noru.

Az egyik háromlábú szamárra ül,

a másik háromszarvú tigrisre.

一塵飛而翳天

一芥墮而覆地

Ichijin tonde ten o kakushi,

Ikke ochite chi o ōu.

Egyetlen porszem felszáll és eltakarja az egész eget,

Egyetlen mustármag lehull és beborítja az egész földet.

一人辯如懸河

一人口似木訥

Ichinin wa ben kenga no gotoku,

Ichinin wa kuchi bokutotsu ni nitari.

Az egyik ember ékesszólása olyan, mint a hadaró patak,

a másik ember beszéde, mint a csökött dadogás.

一喝大地震動

一棒須彌粉碎

Ikkatsu daichi shindō shi,

Ichibō shumi funsai su.

Egy ordítás, és a nagy föld megremeg;

Egy botcsapás, és a Szumeru-hegy darabokra hullik.

去年貧未是貧

今年貧始是貧

Kyonen no hin wa imada kore hin narazu,

Konnen no hin wa hajimete kore hin.

Ínségem tavaly nem volt túl szegény,

Idén jött meg a valódi nyomor.

Hsziang-jen Cse-hszien (?-898) versére utal:

Hsziang-jen remetekunyhója előtt az ösvényt takarította. Félredobott egy követ, mely véletlenül száron vágott egy bambusznádat. Az éles csattanásra egyszeriben megvilágosult:

「去年貧未是貧,今年貧始是貧。去年貧,猶有卓錐之地;今年貧,錐也無。」

Ínségem tavaly nem volt túl szegény,

idén jött meg a valódi nyomor.

Tavaly volt még föld a kapám hegyén,

de kapám is odalett az idén.

鴈無遺蹤之意

水無沈影之心

Kari ni ishō no i naku,

Mizu ni chin'ei no kokoro nashi.

Tóra vetül vadlúd-árnyék,

nincsen ebben semmi szándék.

Nem érez a tó sem vágyat:

viseljen a tükrén árnyat.

Haikuvá fordítva:

vándormadarak

tóra vetett árnyukat

magukkal visziktovaszállt gólyák

árnyat vetni a tóra

nem is akartak*

Zenrin kusú, Kepes János fordítása Alan W. Watts angol verziójából.

In: A zen útja, 1997:A vadlúd képe nem szándékkal vetül rá;

A víz sem igyekszik, hogy befogadja.*

Vö. két nyugati verssel:

Húznak a ludak magasan,

Elmennek innen, okosan.

Messzire mennek jég, hó elöl –

Ne nézz rájuk: a vágy megöl.Jékely Zoltán: Altató (részlet, 1949. október 9.)

Ahogy a kő fölött beforr a hab,

ahogy a gyűrű szétfut a hangtalan vizen -

a végén ránctalan nemlét marad,

mintha sosem lett volna semmi sem.Rakovszky Zsuzsa: Dal az időről (részlet, 1988)

水至淸則無魚

人至察則無徒

Mizu itatte kiyoki toki wa uo naku,

Hito itatte akiraka naru toki wa to nashi.

A teljesen tiszta vízben nincs hal;

A teljesen nyitott embernek nincsenek társai.

猛虎口中奪鹿

饑鷹爪下分兎

Mōko kuchū ni shika o ubai,

Kiyō sōka ni to o wakatsu.

Ragadd ki a szarvast a vad tigris szájából,

Szabadítsd ki a nyulat az éhes sólyom karmából.

戰戰兢兢

如臨深淵

如履薄氷

Sen-sen kyō-kyō to shite,

Shin’en ni nozomu ga gotoku,

Hakuhyō o fumu ga gotoshi.

Légy óvatos és éber,

Mintha egy szakadékba nézel,

Mintha járnál vékony jégen.

Légy szelídebb, készségesebb

ágra gyűlő madárkáknál,

óvakodó, félni serény,

mintha mélység szélén járnál.

Remegj, mintha utad gyenge,

igen gyenge jégen vinne.Lator László fordítása

In: Si King - Dalok könyve, 196.

Tizenhárom írásjegyből álló kifejezések

有佛處住不得

無佛處急須走過

Ubutsu no tokoro jū suru koto o ezare,