Terebess

Gábor

A

pléhbogrács romantikája, avagy az ausztrál billy

tea

Barkochba:

– Személy?

– Igen.

– Pléhből van?

– Igen.

– Rákérdezek. Billy.

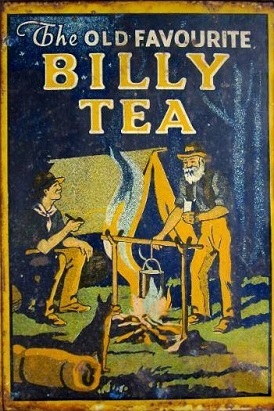

Ott Lenn Alul (Down Under = Ausztrália), Kinn Hátul (the Outback), a bozótvidéken (in the bush) – a billy teafőzés egy drótfüllel ellátott nagy (kb. kétliteres) üres konzervdobozban (billy can) történik, szabadtűzön.

Ez az igazi 'wabi-cha'. Mennyivel szerényebb és természetesebb a japánnál. Az ausztrál teaszertartás!

A konzervdoboz használat visszanyúlik az aranyláz idejére, amikor a Franciaországból importált nagyméretű, kiürült marhahúsos konzervdobozokban kezdtek el teát főzni az aranyásók. Idővel a 'bullybeef' can-ből billy can lett.

Víz leginkább egy billabongban található, a folyók holtágaiban, ahol Ausztráliában sokszor tovább megmarad a víz, mint magában az élő folyóban.

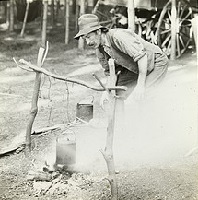

(Emlékszem, amikor a Stradbroke-szigeten dolgoztam 1970-ben

egy kőbányában, hasztalan ittunk vizet, a szubtrópusi hőségben

csak a várva-várt déli billy tea oltotta szomjunkat.

A forró ital tudta csak leöblíteni kiszáradt torkunkat,

a beindult verejtékezés és párolgása pedig lehűtött.

Itt egy haikum abból az időből:Szomjoltó forró

teára vágysz, s egész nap

hideget vedelsz.Nem kellett sokat bajlódni a tűzrakással, csak összeszedtünk

néhány száraz eukaliptusz-ágat, amin rajta maradtak

az elszáradt levelek. Égett, mint a zsír.)Ha az edény kétharmadáig töltött víz felforrt, beledobnak egy marék feketeteát, néha egy-két eukaliptusz-levelet is ízesítésül, az nő szinte mindenütt,

majd könyökből körbeforgatják öt-hatszor, hogy a teafű leülepedjen a konzervdoboz aljára.

(Ezt a körbe-lóbálást azért ne forró teával gyakoroljuk!

Kezdetben elégedjünk meg azzal, hogy oldalba veregetjük

a billy cant egy ággal, a teafű ettől is elég jól leülepszik.)Egy ütött-kopott, kormos, agyonhasznált billy can tulajdonosa büszkesége. Eszébe nem jutna újra cserélni. Eszébe nem jutna nélküle nekivágni a bozótnak.

Minden egyes billy teafőzés tisztelgés a felfedező, a telepes, az aranyásó, a (ma már büszkén vallott) fegyenc ősök előtt. Hagyomány őrzése és felidézése. Időgép nélkül visszavisz a múltba.

A maradék tea, ha van, mindig a tábortűz rituális eloltására szolgál.

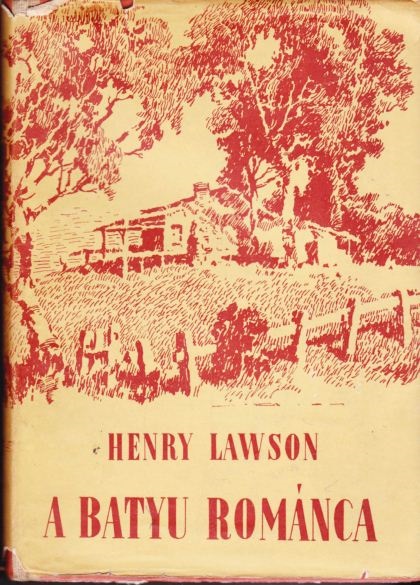

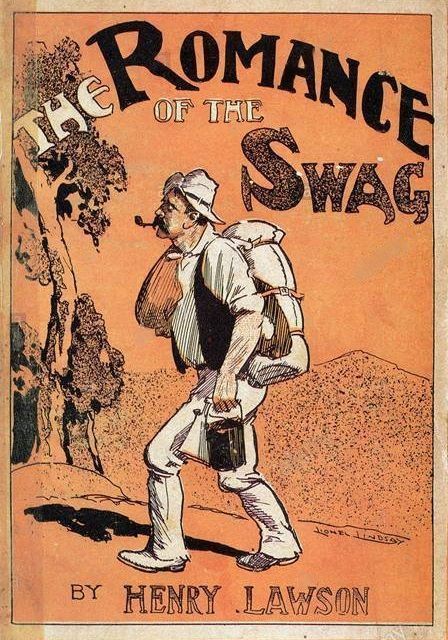

A teafőző pléhbogrács kultuszához kapcsolódik a leghíresebb bozótballada, a Waltzing Matilda (1895), amely mondhatni Ausztrália nemhivalatos himnusza lett, valamint a gyarmati idők első nagy ausztrál elbeszélője, Henry Lawson (1867-1922) irodalmi munkássága.

Vissza

az Ausztrália oldalra

Teakult,

a Terebess Online különlapja

Terebess

Gábor: Ausztrál fűszerek

Henry Lawson

A batyu románca : elbeszélések

ford. Szentkuthy Miklós; a verseket ford. Bakucz József; ill. Pituk József

A fordítást az eredetivel egybevetette: Ottlik Géza

Budapest : Új Magyar Kiadó, 1956, 407 oldal

Csaknem félszáz elbeszélés tükrében ismerteti meg ez a kötet a magyar olvasóval Henry Lawsont, Ausztrália nagy klasszikus íróját. Aranyásók és birkanyírók, munkások és vándorlegények a hősei Lawson írásainak. Nagy szeretettel, megértéssel ír Ausztrália egyszerű embereiről, hiszen ő maga is köztük élt, velük dolgozott, szenvedett, örült — és nekik szentelte életművét. Elbeszéléseit ragyogó humorral szövi át, bőven merít a népnyelv ízes elemeiből.

Aki hű képet akar kapni a 19. század végi — 20. század eleji Ausztráliáról: olvassa el Lawson mélységesen realista műveit, az ausztráliai nép életének valóságos enciklopédiáját. (Fülszöveg)

Tartalom

Honfoglalás |

|

Honfoglalás Settling on the Land (1893) |

7 |

Nem asszonynak való hely ez No Place for a Woman (1900) |

14 |

Andy Page vetélytársa Andy Page's Rival (1899) |

25 |

Majd a Péter... Middleton's Peter (1900) |

34 |

A hajcsár felesége The Drover's Wife (1892) |

43 |

A batyu románca |

|

A batyu románca The Romance of the Swag (1907) |

55 |

Beszélgetés tábortűznél A Camp-Fire Yarn (1893) |

62 |

Mitchell (Pillanatfelvétel) Mitchell: A Character Sketch (1893) |

66 |

Mert ez az én kutyám bizony olyan That There Dog O' Mine (1893) |

69 |

A finánc The Exciseman (1910) |

72 |

A »Döglött Dingó«-ban At Dead Dingo (1901) |

80 |

»Elbocsátás? Fütyülök rá!« Mitchell Doesn't Believe in the Sack (1893) |

85 |

Stiffner és Jim (harmadsorban Bill) Stiffner and Jim (Thirdly, Bill) (1894) . . |

87 |

Körbe a kalappal! Send Round the Hat (1902) |

95 |

A kocsmáros felesége The Shanty-Keeper's Wife (1896) |

117 |

Dave Regan titka The Mystery of Dave Regan (1894) |

124 |

A márványfa forgácsa The Iron-Bark Chip (1900) |

128 |

A birkanyíró álma The Shearer's Dream (1902) |

134 |

Steelman Steelman (1895) |

139 |

Egy kis baj a geológia körül The Geological Spieler (1896) |

143 |

Portyázás potyáért On the Tucker Track : A Steelman Story (1902) |

153 |

Steelman tanítványa Steelman's Pupil (1895-1833) |

157 |

Kárhozottak Szállodája The Lost Soul's Hotel (1902) |

163 |

Pipacs-dűlő |

|

Járda szélén vagy erdő mélyén ‘Dossing out' and ‘camping' (1893) |

179 |

Két kölyök a vagongyárban Two Boys at Grinder Bros (1900) |

184 |

Arvie Aspinall ébresztőórája Arvie Aspinall's Alarm Clock (1892) |

189 |

Részvétlátogatás A Visit of Condolence (1892) |

193 |

Pipacs-dűlő Jones's Alley (1896) |

198 |

Lakás és ellátás Board and Residence (1894) |

212 |

Vén cimborák, ha találkoznak Meeting Old Mates (1900) |

218 |

Hazajáró lélek Drifted Back (1894) |

226 |

Kicsit romlik a szeme Going Blind (1895) |

229 |

Mégiscsak a hazája |

|

Mégiscsak a hazája... His Country — After All (1894) |

237 |

Macskák a vadonban Bush Cats (1894) |

243 |

Két kutya meg egy kerítés Two Dogs and a Fence (1895) |

248 |

Gyarmati virágnyelv His Colonial Oath (1893) |

251 |

Szakszervezeti temetés The Union Buries Its Dead (1893) |

253 |

Redclay hőse The Hero of Redclay (1900) |

259 |

Színarany |

|

Nemezis His Father's Mate (1888) |

281 |

Apátok öreg cimborája An Old Mate of your Father's (1893) |

293 |

Négylábú bomba The Loaded Dog (1899) |

298 |

Színarany Payable Gold (1891) |

307 |

»Utánaküldendő!« Remailed (1894) |

314 |

Joe Wilson |

|

Joe Wilson udvarol Joe Wilson's Courtship (1900) |

321 |

Brighten sógornője Brighten's Sister-in-Law (1900) |

355 |

| Négyüléses homokfutó A Double Buggy at Lahey's Creek (1899-1900) | 381 |

Henry Lawson |

405 |

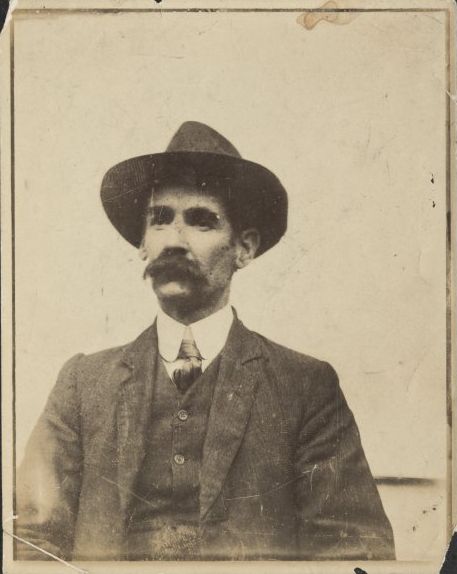

HENRY LAWSON

(1867-1922)

A XIX. század közepén az ausztráliai Victoria gyarmaton aranyat

találtak és az »aranyláz« kivándorlók százezreit vonzotta az

új »Ígéret Földjére«. 1851 és 1861 között Ausztrália lakossága

csaknem megháromszorozódott.Henry Lawson apja, Peter Larsen norvég tengerész is ezekkel

a kivándorlókkal ment Ausztráliába.Az aranymezőkön nem találta meg a szerencséjét, ezért más

mesterséggel próbálkozott; végül sikerült egy kis farmot

vásárolnia.A küzdelmes élet, gyakori ínség és szüleinek rossz házassága

kitörölhetetlen nyomot hagyott Henry lelkében. Számos írásában

bukkannak fel gyermekkori emlékei. Magányos gyerek volt,

sokat olvasott, főleg Dickens, Frederick Marryat és az ausztráliai Clarke

műveit, és XVIII-XIX. századbeli kalandregényeket. Tizennégy

éves korában otthagyta az iskolát és apja mellett kezdett dolgozni.

Hosszú időn át együtt vándoroltak az országban, ács- és

mázolómunkát végeztek.Lawson már ekkor írt verseket és rövid karcolatokat; ezeket

beküldte a vidéki lapoknak. Később Sydney egyik külvárosában

telepedett le: mint segédmunkás dolgozott a Hudson Fivérek üzemében

(amelyet később »Grinder és Testvére« néven írt le több

elbeszélésében). Sydney egyik nyomornegyedében lakott.1887-től kezdve sorra jelentek meg versei, majd később elbeszélései

a sydneyi BULLETIN hasábjain. Írásaiból azonban nem

tudott megélni. Munkát keresve vándorolt az országban, kétszer

Új-Zélandban is járt, fűrésztelepen dolgozott, villanyszerelő volt,

majd tanító egy maori-iskolában.Már ebben az időben sokat írt a szocialista sajtóban. Első önálló

kötete 1894-ben jelent meg: kilencvenhat oldalas vers- és

novellagyűjtemény. 1896-ban két újabb kötetét a kritika jól

fogadta, de nem sokat keresett velük. 1899 januárjában egy cikkében

elmondja, hogy tizenkét esztendei írói munkássága hétszáz

fontot jövedelmezett.1900 áprilisában Lawson családostul Angliába hajózott, hogy

ott próbáljon boldogulni. Eleinte sikere is volt: másfél év alatt

három kötete jelent meg. Később azonban Lawsonné súlyosan

megbetegedett, Lawson pedig inni kezdett. Mindkettőjüket gyötörte

a honvágy, és 1902 végén hazatértek Ausztráliába. Házasságuk

nem volt szerencsés, hamarosan el is váltak.Az első világháborúig Lawsonnak további öt kötete jelent meg,

a háború alatt azonban csaknem teljesen visszavonult, mindössze

egy verskötetet adott ki 1915-ben. Egészségi állapota mindinkább

romlott — ezt természetesen alkotóképessége is megsínylette.

Ezután már csak kisebb cikkeket közölt különféle lapokban.

Élete utolsó éveiben segélyekből élt; kiadóitól jelentéktelen

járadékot kapott: ebből tartotta fenn magát 1922. szeptember 2-án

bekövetkezett haláláig.

(Borbás Mária)

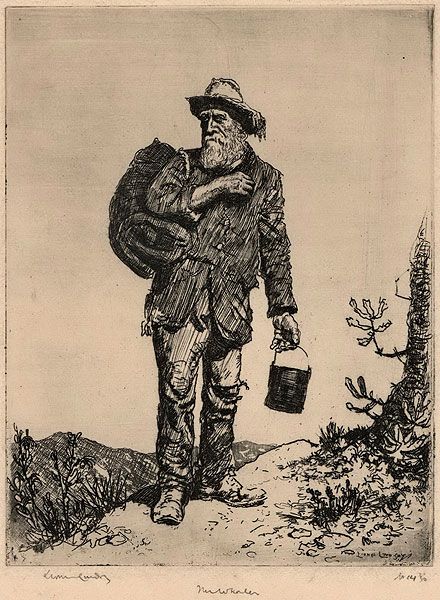

Norman Lindsay (1879-1969) könyvborítói

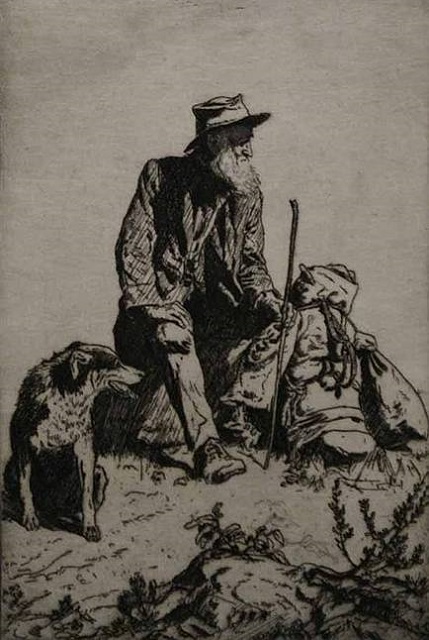

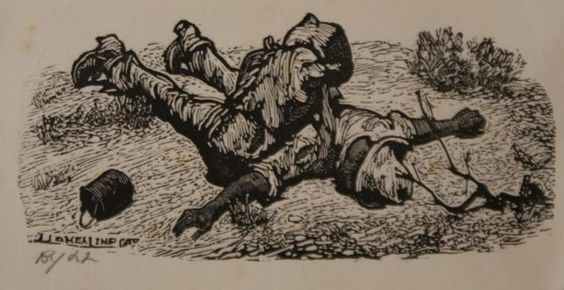

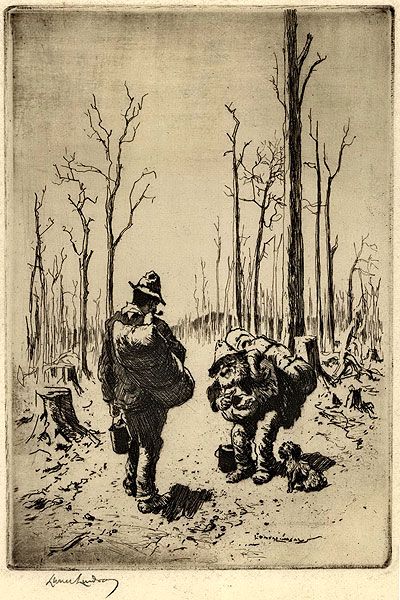

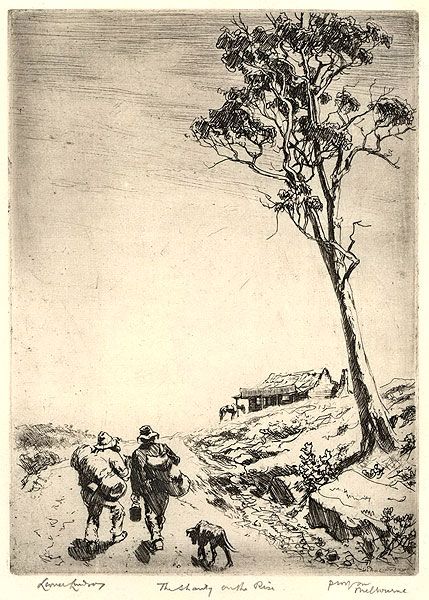

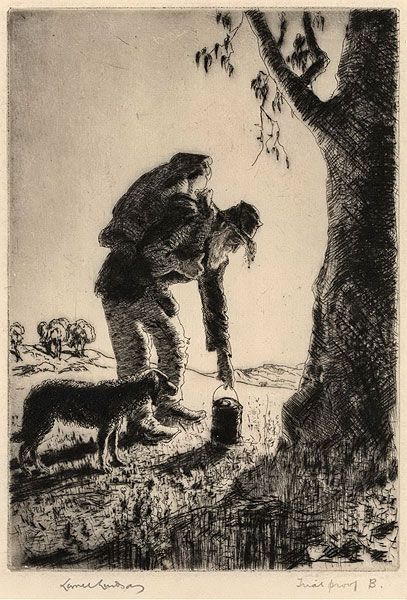

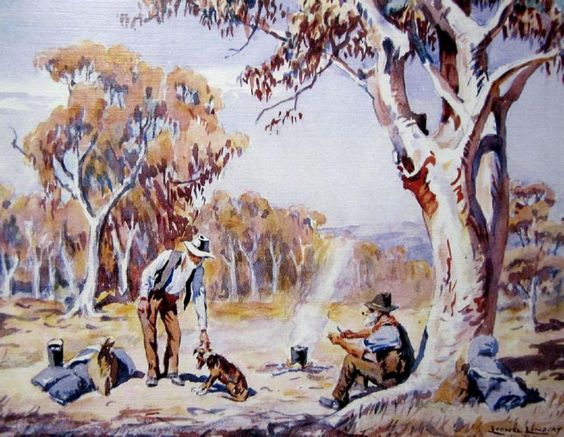

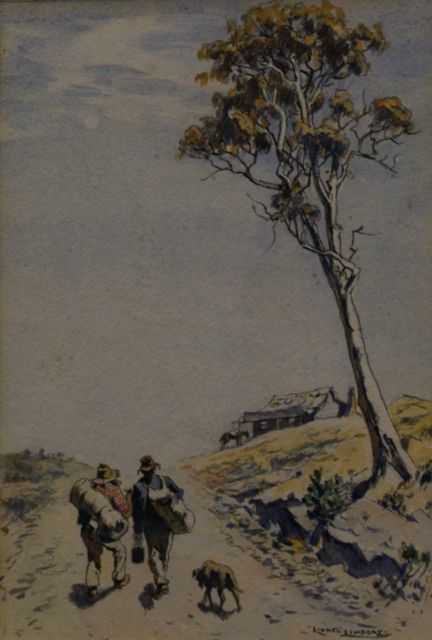

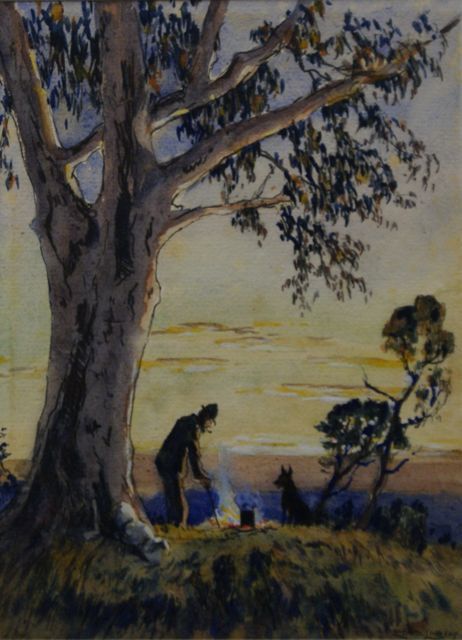

Lionel Lindsay (1874–1961) könyvborítója és illusztrációja

THE ROMANCE OF THE SWAG by Henry Lawson 1907 |

A BATYU ROMÁNCA Henry Lawson elbeszélése Szentkuthy Miklós fordítása |

THE Australian swag fashion is the easiest way in the world of carrying a load. I ought to know something about carrying loads: I've carried babies, which are the heaviest and most awkward and heartbreaking loads in this world for a boy or man to carry, I fancy. God remember mothers who slave about the housework (and do sometimes a man's work in addition in the bush) with a heavy, squalling kid on one arm! I've humped logs on the selection, “burning-off,” with loads of fencing-posts and rails and palings out of steep, rugged gullies (and was happier then, perhaps); I've carried a shovel, crowbar, heavy “rammer,” a dozen insulators on an average (strung round my shoulders with raw flax)—to say nothing of soldiering kit, tucker-bag, billy and climbing spurs—all day on a telegraph line in rough country in New Zealand, and in places where a man had to manage his load with one hand and help himself climb with the other; and I've helped hump and drag telegraph-poles up cliffs and sidings where the horses couldn't go. I've carried a portmanteau on the hot dusty roads in green old jackeroo days. Ask any actor who's been stranded and had to count railway sleepers from one town to another! he'll tell you what sort of an awkward load a portmanteau is, especially if there's a broken-hearted man underneath it. I've tried knapsack fashion—one of the least healthy and most likely to give a man sores; I've carried my belongings in a three-bushel sack slung over my shoulder—blankets, tucker, spare boots and poetry all lumped together. I tried carrying a load on my head, and got a crick in my neck and spine for days. I've carried a load on my mind that should have been shared by editors and publishers. I've helped hump luggage and furniture up to, and down from, a top flat in London. And I've carried swag for months out back in Australia—and it was life, in spite of its “squalidness” and meanness and wretchedness and hardship, and in spite of the fact that the world would have regarded us as “tramps”—and a free life amongst men from all the world The Australian swag was born of Australia and no other land—of the Great Lone Land of magnificent distances and bright heat; the land of self-reliance, and never-give-in, and help-your-mate. The grave of many of the world's tragedies and comedies—royal and otherwise. The land where a man out of employment might shoulder his swag in Adelaide and take the track, and years later walk into a hut on the Gulf, or never be heard of any more, or a body be found in the bush and buried by the mounted police, or never found and never buried—what does it matter? The land I love above all others—not because it was kind to me, but because I was born on Australian soil, and because of the foreign father who died at his work in the ranks of Australian pioneers, and because of many things. Australia! My country! Her very name is music to me. God bless Australia! for the sake of the great hearts of the heart of her! God keep her clear of the old-world shams and social lies and mockery, and callous commercialism, and sordid shame! And heaven send that, if ever in my time her sons are called upon to fight for her young life and honour, I die with the first rank of them and be buried in Australian ground. But this will probably be called false, forced or “maudlin sentiment” here in England, where the mawkish sentiment of the music-halls, and the popular applause it receives, is enough to make a healthy man sick, and is only equalled by music-hall vulgarity. So I'll get on. In the old digging days the knapsack, or straps-across-the chest fashion, was tried, but the load pressed on a man's chest and impeded his breathing, and a man needs to have his bellows free on long tracks in hot, stirless weather. Then the “horse-collar,” or rolled military overcoat style—swag over one shoulder and under the other arm—was tried, but it was found to be too hot for the Australian climate, and was discarded along with Wellington boots and leggings. Until recently, Australian city artists and editors—who knew as much about the bush as Downing Street knows about the British colonies in general—seemed to think the horse-collar swag was still in existence; and some artists gave the swagman a stick, as if he were a tramp of civilization with an eye on the backyard and a fear of the dog. English artists, by the way, seem firmly convinced that the Australian bushman is born in Wellington boots with a polish on 'em you could shave yourself by. The swag is usually composed of a tent “fly” or strip of calico (a cover for the swag and a shelter in bad weather—in New Zealand it is oilcloth or waterproof twill), a couple of blankets, blue by custom and preference, as that colour shows the dirt less than any other (hence the name “bluey” for swag), and the core is composed of spare clothing and small personal effects. To make or “roll up” your swag: lay the fly or strip of calico on the ground, blueys on top of it; across one end, with eighteen inches or so to spare, lay your spare trousers and shirt, folded, light boots tied together by the laces toe to heel, books, bundle of old letters, portraits, or whatever little knick-knacks you have or care to carry, bag of needles, thread, pen and ink, spare patches for your pants, and bootlaces. Lay or arrange the pile so that it will roll evenly with the swag (some pack the lot in an old pillowslip or canvas bag), take a fold over of blanket and calico the whole length on each side, so as to reduce the width of the swag to, say, three feet, throw the spare end, with an inward fold, over the little pile of belongings, and then roll the whole to the other end, using your knees and judgment to make the swag tight, compact and artistic; when within eighteen inches of the loose end take an inward fold in that, and bring it up against the body of the swag. There is a strong suggestion of a roley-poley in a rag about the business, only the ends of the swag are folded in, in rings, and not tied. Fasten the swag with three or four straps, according to judgment and the supply of straps. To the top strap, for the swag is carried (and eased down in shanty bars and against walls or veranda-posts when not on the track) in a more or less vertical position—to the top strap, and lowest, or lowest but one, fasten the ends of the shoulder strap (usually a towel is preferred as being softer to the shoulder), your coat being carried outside the swag at the back, under the straps. To the top strap fasten the string of the nose-bag, a calico bag about the size of a pillowslip, containing the tea, sugar and flour bags, bread, meat, baking-powder and salt, and brought, when the swag is carried from the left shoulder, over the right on to the chest, and so balancing the swag behind. But a swagman can throw a heavy swag in a nearly vertical position against his spine, slung from one shoulder only and without any balance, and carry it as easily as you might wear your overcoat. Some bushmen arrange their belongings so neatly and conveniently, with swag straps in a sort of harness, that they can roll up the swag in about a minute, and unbuckle it and throw it out as easily as a roll of wall-paper, and there's the bed ready on the ground with the wardrobe for a pillow. The swag is always used for a seat on the track; it is a soft seat, so trousers last a long time. And, the dust being mostly soft and silky on the long tracks out back, boots last marvellously. Fifteen miles a day is the average with the swag, but you must travel according to the water: if the next bore or tank is five miles on, and the next twenty beyond, you camp at the five-mile water to-night and do the twenty next day. But if it's thirty miles you have to do it. Travelling with the swag in Australia is variously and picturesquely described as “humping bluey,” “walking Matilda,” “humping Matilda,” “humping your drum,” “being on the wallaby,” “jabbing trotters,” and “tea and sugar burglaring,” but most travelling shearers now call themselves trav'lers, and say simply “on the track,” or “carrying swag.” And there you have the Australian swag. Men from all the world have carried it - lords and low-class Chinamen, saints and world martyrs, and felons, thieves, and murderers, educated gentlemen and boors who couldn't sign their mark, gentlemen who fought for Poland and convicts who fought the world, women, and more than one woman disguised as a man. The Australian swag has held in its core letters and papers in all languages, the honour of great houses, and more than one national secret, papers that would send well-known and highly-respected men to jail, and proofs of the innocence of men going mad in prisons, life tragedies and comedies, fortunes and papers that secured titles and fortunes, and the last pence of lost fortunes, life secrets, portraits of mothers and dead loves, pictures of fair women, heart-breaking old letters written long ago by vanished hands, and the pencilled manuscript of more than one book which will be famous yet. The weight of the swag varies from the light rouseabout's swag, containing one blanket and a clean shirt, to the “royal Alfred,” with tent and all complete, and weighing part of a ton. Some old sundowners have a mania for gathering, from selectors' and shearers' huts, and dust-heaps, heart-breaking loads of rubbish which can never be of any possible use to them or anyone else. Here is an inventory of the contents of the swag of an old tramp who was found dead on the track, lying on his face on the sand, with his swag on top of him, and his arms stretched straight out as if he were embracing the mother earth, or had made, with his last movement, the sign of the cross to the blazing heavens Rotten old tent in rags. Filthy blue blanket, patched with squares of red and calico. Half of “white blanket” nearly black now, patched with pieces of various material and sewn to half of red blanket. Three-bushel sack slit open. Pieces of sacking. Part of a woman's skirt. Two rotten old pairs of moleskin trousers. One leg of a pair of trousers. Back of a shirt. Half a waistcoat. Two tweed coats, green, old and rotting, and patched with calico. Blanket, etc. Large bundle of assorted rags for patches, all rotten. Leaky billy-can, containing fishingline, papers, suet, needles and cotton, etc. Jam-tin, medicine bottles, corks on strings, to hang to his hat to keep the flies off (a sign of madness in the bush, for the corks would madden a sane man sooner than the flies could). Three boots of different sizes, all belonging to the right foot, and a left slipper. Coffeepot, without handle or spout, and quart-pot full of rubbish—broken knives and forks, with the handles burnt off, spoons, etc., picked up on rubbish-heaps; and many rusty nails, to be used as buttons, I suppose. Broken saw blade, hammer, broken crockery, old pannikins, small rusty frying-pan without a handle, children's old shoes, many bits of old bootleather and greenhide, part of yellowback novel, mutilated English dictionary, grammar and arithmetic book, a ready reckoner, a cookery book, a bulgy angloforeign dictionary, part of a Shakespeare, book in French and book in German, and a book on etiquette and courtship. A heavy pair of blucher boots, with uppers parched and cracked, and soles so patched (patch over patch) with leather, boot protectors, hoop-iron and hobnails that they were about two inches thick, and the boots weighed over five pounds. (If you don't believe me go into the Melbourne Museum, where, in a glass case in a place of honour, you will see a similar, perhaps the same, pair of bluchers labelled “An example of colonial industry.”) And in the core of the swag was a sugar-bag tied tightly with a whip-lash, and containing another old skirt, rolled very tight and fastened with many turns of a length of clothes-line, which last, I suppose, he carried to hang himself with if he felt that way. The skirt was rolled round a small packet of old portraits and almost indecipherable letters—one from a woman who had evidently been a sensible woman and a widow, and who stated in the letter that she did not intend to get married again as she had enough to do already, slavin' her finger-nails off to keep a family, without having a second husband to keep. And her answer was “final for good and all,” and it wasn't no use comin' “bungfoodlin'” round her again. If he did she'd set Satan on to him. “Satan” was a dog, I suppose. The letter was addressed to “Dear Bill,” as were others. There were no envelopes. The letters were addressed from no place in particular, so there weren't any means of identifying the dead man. The police buried him under a gum, and a young trooper cut on the tree the words: SACRED TO THE MEMORY OF |

Ha már mindenképpen valami terhet kell cipelned, nincs jobb Az ausztráliai batyu Ausztráliában született, ott bizony és Ez az az ország, melyet mindenekfölött szeretek — nem mert No de hát Angliában ezt bizonyára »hamis hang«-nak A régi, aranylázas napokban kipróbálták a hátizsákot vagy A batyu alkatrészei rendszerint a következők: egy darab karton Igen: ez az ausztráliai batyu. A világ mind a négy sarkából A batyu súlya a legkülönbözőbb lehet, a könnyű fogjad-hordjad Szennyes, ócska sátor, rongyokban. Mocskos kék pokróc, Egy fűrész törött pengéje, kalapács, törött cserép, horpadt A levél »Kedves Bill«-nek szólt, hasonlóképpen a többi is. Itt nyugszik az Úrban |

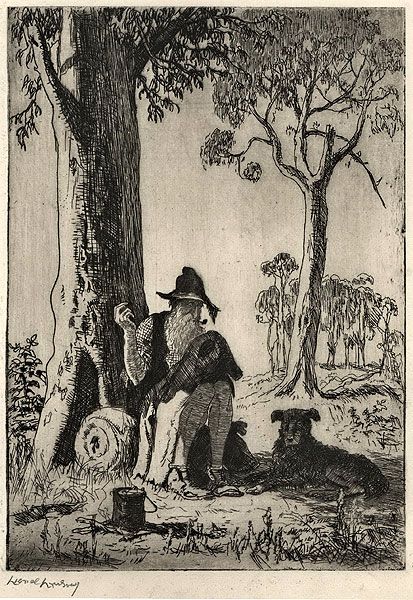

Lionel Lindsay (1874–1961) illusztrációi

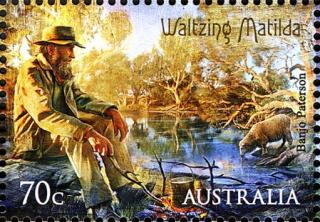

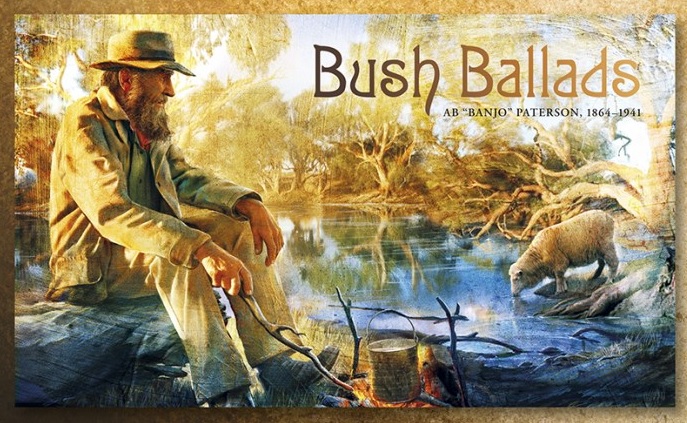

Australia Postage Stamp - Bush Ballads by A.B. 'Banjo' Paterson (1864-1941). Issued 13 May 2014.

Waltzing Matilda Lyrics by A.B. 'Banjo' Paterson (1864-1941) written at old Dagworth Homestead, Queensland, Australia in January 1895 Australia's unofficial National Anthem |

A.B. 'Banjo' Paterson (1864-1941): Kóbor Matilda Bozótballada, 1895 Terebess Gábor fordítása |

Once a jolly swagman camped by a billabong Chorus: |

Derék vándor vert tábort egy billabongnál Refrén: Kósza birka jött inni a billabonghoz Tanyásgazda nyargalt telivéren. Beugrott a vándor a mély billabongba. |

Ausztrál tájszótár

bush ballad = bozótballada

to waltz Matilda = tekeregni Matildával, azaz körbejárni matrackával az ausztrál bozótvidéket, batyuval barangolni

swag = málha, batyu, (felgöngyölt) derékalj, úti-ágy, Matilda/matracka

swagman = batyus vándormunkás, zsellér, béres, vadonjáró, (olykor guberáló-tarháló-lopkodó) csavargó

billabong = holtág, morotva, tó

coolibah tree = kuliba-fa, egyfajta eukaliptusz-fa

billy(can) = pléhbogrács, konzervdobozból drót füllel barkácsolt teaforraló

jumbuck = birka

tucker = élelem

tucker bag = elemózsiás tarisznya, ételzsák, szeredás

squatter = telepes, tanyásgazda, földfoglaló, jószágtartó nagybirtokos

trooper = zsandár, pandúr

Lionel Lindsay (1874–1961) illusztrációja

Waltzing Matilda

az ausztrál countryzene királya, Slim Dusty (1927-2003) előadásában: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CwvazMc5EfE

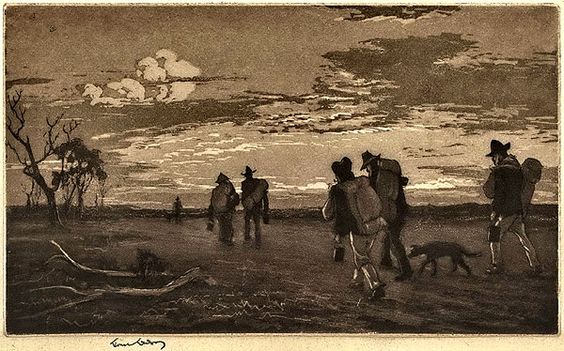

Lionel Lindsay (1874–1961) metszetei és vízfestményei

![]()

Billycan

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A billycan is a lightweight cooking pot in the form of a metal bucket commonly used for boiling water, making tea or cooking over a campfire or to carry water. These utensils are more commonly known simply as a billy or occasionally as a billy can (billy tin or billy pot in Canada).

The term billy or billycan is particularly associated with Australian usage, but is also used in New Zealand, Britain and Ireland.

It is widely accepted that the term "billycan" is derived from the large cans used for transporting bouilli or bully beef on Australia-bound ships or during exploration of the outback, which after use were modified for boiling water over a fire; however there is a suggestion that the word may be associated with the Aboriginal billa (meaning water; cf. Billabong).

In Australia, the billy has come to symbolise the spirit of exploration of the outback and is a widespread symbol of bush life, although now regarded mostly as a symbol of an age that has passed.

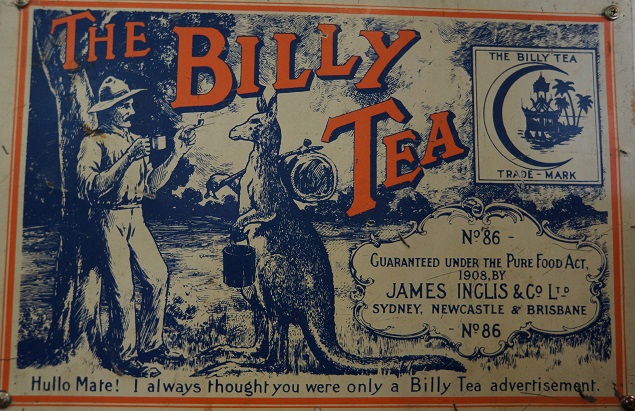

To boil the billy most often means to make tea. "Billy Tea" is the name of a popular brand of tea long sold in Australian grocers and supermarkets. Billies feature in many of Henry Lawson's stories and poems. Banjo Paterson's most famous of many references to the billy is surely in the first verse and chorus of Waltzing Matilda: "And he sang as he looked at the old billy boiling", which was later changed by the Billy Tea Company to "And he sang as he watched and waited 'til his billy boiled...".

Links to the books of Henry Lawson (1867-1922) on the internet:

While the billy boils: the original newspaper versions

http://www.ironbarkresources.com/henrylawson/index4.html

http://adc.library.usyd.edu.au/search?creator=Lawson,%20Henry%20(1867-1922)

Billycans

http://www.slsa.sa.gov.au/manning/sa/misc/billy.htm#billycans

The origin of the "billycan" is traversed in the Register, 1 December 1916, page 9e:

Passengers on board early sailing ships were treated twice a week with bouilli soup... It was [contained] in half-gallon cans [and] when emptied and fitted with a handle [they] were... used for the purpose of boiling water for tea making and a host of other purposes... The Australian adaptability... found no difficulty in transposing bouilli[can] to billycan!

Oh, Soup and Bouilli, subject of song,

What bilious contents to thy red cans belong,

What glorious sensations it strikes to the heart,

When the soup and gravy from the red cans depart.(Reminiscences of James Chittleborough (ex Buffalo) in the Advertiser, 29 November 1912, page 12b.)

Symbols of Australia: Billy

National Museum of Australia

http://www.nma.gov.au/exhibitions/symbols_of_australia/billy

A practical companion and a mateThe billy is an Australian term for a metal container used for boiling water, making tea or cooking over a fire.

By the end of the 19th century the billy had become as natural, widespread and symbolic of bush life as the gum tree, the kangaroo and the wattle.

The billy was cheap, lightweight and versatile. But its elevation to symbolic status stemmed from more than its practicality.

Australians invested it with human qualities such as reliability, hospitality and egalitarianism — qualities that were celebrated as distinctively Australian. The billy became a source of comfort and companionship; ultimately it became a mate.

The billy today is largely an object of nostalgia, symbolic of a way of life that has almost disappeared.

A traditional billycan on a campfire

The swagman, his billy and Waltzing Matilda

Waltzing Matilda is an unofficial Australian anthem, with lyrics written in 1895 by bush poet Banjo Paterson. However, the version most Australians are familiar with was rewritten by the Billy Tea Company in 1903.

In the new version of the song the line ‘he sang and he looked at the old billy boiling' was replaced by ‘he sang and he watched and waited till his “Billy” boiled', thus stressing the connection to Billy Tea. This new line was also inserted into the chorus, ensuring maximum exposure for the ‘Billy' brand.

As Federation approached, many Australians looked to the bush as representing the ‘real' Australia. Sketches, stories, poems and art about bush life invariably included the billy.

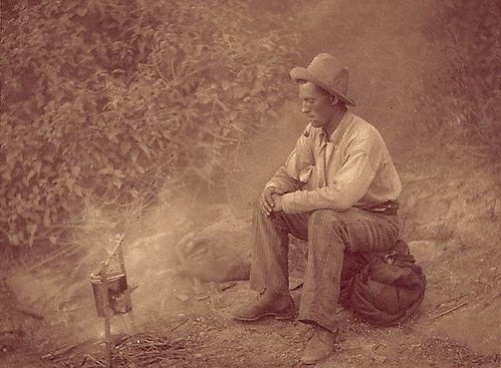

Swagman, Walbundry Station, Riverina District NSW, 1901In particular it was linked to the swagman, the nomadic traveller in search of work, who is also the central character in Waltzing Matilda. It was around the boiling billy that the great Australian yarn was spun.

At the same time as it was a symbol of bush hospitality it also represented the democratic, self-reliant Australian spirit.

Many young and newer Australians, even if they are familiar with the words of Waltzing Matilda, may be unaware of what a billy is.

A ‘bushies' birthright?

For bushwalkers, the billy served as a connection to an ‘authentic' bush culture well into the twentieth century.

‘Bushies' still use billies, tourists on outback holidays are offered billy tea, and billy-boiling competitions are held at country shows.

Restrictions on fire use in national parks, however, has limited the use of the billy, and some bushwalkers complained bitterly of being denied access to an Australian birthright — the campfire and the opportunity to boil the billy.

While the Billy Boils, 1908 (carbon photograph by Harold Cazneaux, 1878-1953)

Making Tea in the Australian Bush

"The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy"

https://h2g2.com/edited_entry/A896628

Whether it is in the cold reaches of the tablelands, the hot flatness of the plains or the sticky humidity of the coastal forests (or anywhere in between for that matter), there is nothing that the sojourner therein could find more refreshing than tea brewed in the authentic way of the bush. Even if the party is there on bush business, brewing a cuppa adds a kind of picnic atmosphere to the occasion 1.

Assuming that one has found an area of bush as yet untrampled and unpolluted (which will obviously later be left as close to that pristine condition as possible) one can then proceed to picnic. A tip: rather than keeping up a continuous 'bush salute' to wave away the sticky little bush flies, don't forget the insect repellent. A basic part of this picnicking is of course the actual brewing ritual. This is a highly satisfying, perhaps even exhilarating process, and there are many ways to go about it.

Why 'Billy'?

It seems originally that large 'bullybeef' cans were cleaned out after use and fitted with a wire handle and used as pots for the purpose of making tea. They eventually became known as 'billycans' part of the pioneering and swagman traditions. This practice may have begun during the gold rush era with the cans of beef imported from France. Later, the commercial can, available in various sizes, became more common, but if the purist wishes to construct his own, it is not difficult. If one goes this far, one should also make tin mugs from smaller containers, such as condensed milk tins. This could be seen as excessive, and can lead to burned fingers.

First Steps

Let us look only at the bare essentials of the process. Never mind the gentrified gas bottle and stove of the effete citified picnicker 2. A true believer would not even take a shovel to dig a firepit, though after selecting a fairly clear patch where no grass or fallen material could catch to start a conflagration, you could choose to collect some rocks to form a containing circle 3.

Fuel is important. First, there should be a sufficiency of dried grass or leaves collected for kindling, as the use of newspaper is frowned upon by purists, which is laid within the circle of stones, or piled evenly on the bare patch of ground.

Lighting Up

Boiling Up

Fill the billycan to about two-thirds full, as any more water will lead to it boiling over when the tea leaves are added. The best billycan is a blackened object, with or without a lid. With a lid, it does not get flakes of ash in it, but the disadvantage is that getting the lid off in order to drop in the tea leaves can be a tricky task unless the lid's handle is left in an already raised position.

Using the aforementioned piece of green wood, manoeuvre the billycan onto the fire, bumping it a little to seat it firmly. If the fire is well made, the water should not take long to boil, especially if a few more twigs are set around it.

It is at this point that the wonderful flavour of the tea is enhanced by judicious addition of some aromatic gumleaves to the flames 5. The tea is best drunk black.

Brewing Up

Ebullition achieved, the tea leaves should be added to taste, given the shortest time to react, and then the can should be lifted very quickly from the fire with the green stick, doing one's best not to get the hairs on one's forearms singed, as this spoils the aroma.

After it is placed securely away from the fire, the side of the can is given a couple of smart raps with the stick, to settle the leaves.

True heroes of the bush may at this point grasp the (cooled) handle of the billycan and swing it, with a circular twist of a muscular wrist, round in a circle at right angles to the ground and above the head, so as to further infuse the tea.

No matter what it is now drunk from, whether it has milk and sugar added or not, there is absolutely nothing more satisfying than bush tea brewed in a billycan 6.

The Last Step

And at the end, there is the satisfying hiss as the last of the tea and the leaves are used to douse the fire, a vitally important step, penultimate to cleaning up the firesite.

1 There are innumerable 'bush safaris' advertised on the net, many of which finish with or make a highlight of a meal of 'Damper and Billy Tea'. Nevertheless, the accomplishment of bush tea-making is more satisfying as an individual effort rather than succumbing to the commercial.

2 Some photographs of the above safaris show the billy hanging over the fire from a tripod. This should be about the limit of permitted assistance.

3 Note here, it is inadvisable to use river stones, as under heat they are prone to exploding for some reason.

4 This bed of coals is useful for barbecues, but that is a separate issue.

5 In the late 19th Century, commercial billy tea, with a registered trademark, began to be manufactured, reproducing the flavour of bush tea.

6 There can be found on the net the version of The Billy of Tea , a song sung to the tune of Bonny Dundee.

Life in the Australian Backblocks

by Edward S. Sorenson

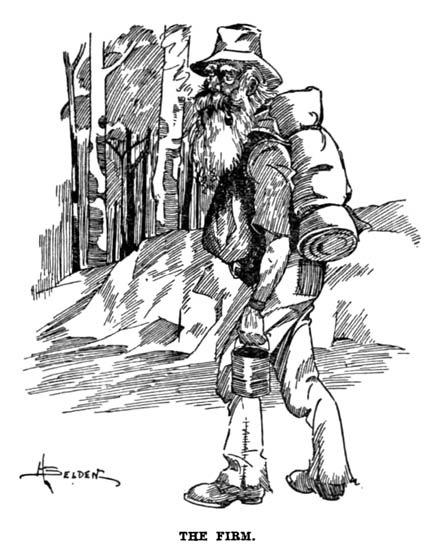

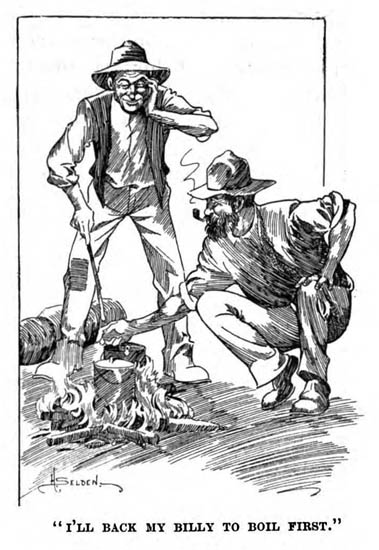

Illustrated by H. Selden

1911

http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks13/1305751h.html

A DISSERTATION ON TRAVELLERS.

The old battler can usually tell at a glance what State a man belongs to by the way he carries his swag. The swags, too, are different. Matilda, of Victoria, has the most taking figure. She is 5 feet or 6 feet long, neat and slim, and tapering at the ends. Her extremes are tied together, and she is worn over the right shoulder and under the left arm—much in the way a lubra wears a skirt. The Banana-lander's¹ pet is short and plump. She is carried perpendicularly between the shoulder-blades, and held in position by shoulder-straps. Getting into this, to a new chum, is like putting on a tight shirt. The Cornstalk² doesn't much care how he rolls his; he merely objects to bulk and weight. Generally it is borne on a slant from right shoulder to left hip, his towel doing duty for shoulder-strap. He chucks it down as though it was somebody else's luggage, and takes it up as if he would much rather leave it behind.

¹ Queenslander's.

² The young countryman in New South Wales

I was once shocked to see Matilda brutally assaulted by a Murrumbidgee whaler. Stopping at a camping spot, he pitched Billy aside with a growl, then took hold of Matilda by her tentacles, swung her high overhead, and banged her on the ground. Then he propelled her violently across the landscape with his boot, unstintedly cursing her in the meantime for not being able to travel on her own.

Neddy, the tucker-bag, or nose-bag, is of more importance than the blue one, and by way of precedence dangles in front, mostly hanging to Matilda's apron-strings. Billy sticks faithfully to the hand that claims him. The exact time when Swaggie, Bluey, Neddy, and Billy first entered into partnership would be hard to determine. Go where you will in the backblocks, and no matter how lonely, dry, and hopeless the track, you will not fail to meet the firm taking its usual walk and going to its customary picnic. Catechetical formula of such meetings: "How far's the next station?" "What's it like for tucker?" "Any one died there lately? No! Then it's no use askin' for work." And, as the firm moves on again, the manager mutters: "Hard lines—nobody won't die."

Nearly everywhere in country parts the term "traveller" is more often heard than "swagman." It is applied to the footman, as though he were the only genuine species of the order that has a habit of moving about. The man with horses, the man on the bike, and the men who trek per medium of vehicles are just as much travellers as the person who "pads the hoof"; but the bush doesn't recognise them in the same light at all. Track society has its castes and classes, its ramifications and complications, like any other society, and its lowest ebb is the sundowner. Too many people are prone to judge the fraternity by its low classes. The word "tramp" to them is almost a criminal suggestion; it came from the Old Country with a bad reputation, and is seldom used by the native-born. On the average, swagmen are as honest and straight-going and just as worthy of respect as their fellows who are in constant billets. They are shearers to-day, drovers to-morrow, and something else later on; and as these billets are not permanent, and good jobs are not in the habit of coming after a man, they must shift from one place to another, and carry their drums on their own backs or on pack-horses. But the man's a man for a' that.

There are all sorts and conditions of men on the track, from men of genius to harmless cranks. There are sons of lords and dukes, heirs to earldoms and vast estates in England—men who had renounced everything rather than marry in accordance with parental tastes and inclinations, as they tell you confidentially. Once on Mount Browne I met the Czar of Russia selling needlewood pipes. He was travelling incognito, and only revealed his identity to me because the inadequate postal service of the back country had temporarily left him without the means of confusing his enemies in vodka. The most amusing are the lonely gentry of Farther Out—men from other lands who have spent lonely years in shepherding, or who made their piles on the goldfields and lost them, having thus sustained the shock of sudden wealth and the more stunning shock of sudden reversion to poverty. I met one on the road to Eromanga, who was dragging his open blanket behind him. Being spread out, and loaded with his effects, it swept the road like a street sweeper. Now and again he would emit an echoing yell and spring into the air, upsetting everything. Slowly and methodically he would gather the properties up, take hold of the ends of the blanket behind him, and start on again. "I'm loaded for Kyabra" he told me, and I put him down for a broken-down teamster. On another track I encountered an excited-looking man, who was riding a brigalow stick, with a swag strapped in front of him, and using his bootlaces for bridle. He was driving an imaginary mob of sheep, and yelling to his dog to "get round them there." The dog couldn't understand, though occasionally he would make a vengeful rush at a flying grasshopper. Then the loony drover would dismount, tie the brigalow colt up to a tree, take off his belt, and chase the dog round and round for splitting up the sheep that weren't there. He cautioned me not to go too near that horse, as he was a terror to kick, having been mounted only for the first time yesterday; and he intimated that he was shorthanded. I wasn't looking for droving just then.

There was a well-known Murrumbidgee whaler in the Wagga district, who had been doing the one circuit—embracing Gundagai, Hay, and Wagga—for thirty odd years, and during the whole of that time had never done a tap of work. He went down one side of the river and up the other, the round occupying from twelve to fifteen months. "A man's a fool to work," he said, and he acted up to it by doing no other toil than carrying his swag.

There are men doing similar circuits in nearly all parts of settled Australia. I knew six who habitually worked a few stations in the lower Buloo and Paroo country. But these occasionally took work, and with the proceeds thereof had a holiday and a jamboree at the wayside pub. That is what they term "going home to mother's." They know every person and place, and every waterhole on the beat; they can tell you how old Spargo's baby is, who is running the show with the Jackson girls, what Anderson is doing now, and when Maloney's slut is likely to have pups. They generally have the promise of one.

The occasional swagman, thrown on the track by force of circumstances, is of a different stamp. He looks upon swagging as the hardest of graft, and the last and lowest calling on earth. He sees only the grim side of the battler's life; the gums whisper no symphonies to him, the birds only mock him, and the benighted bush is a horror that gets on his nerves. He is no companion for the old hand who looks up at his favourite stars and says, "It's time to turn in," and, making a pillow with his boots and spare suit, goes peacefully to sleep. He may tramp for months, tramp thousands of miles, through all weathers and seasons, before he gets work; but he never loses heart, and is just as cheerful at the end as when he set out.

All men who pad the hoof do not carry the swag on the back. Some years ago a fossicker gained some renown by wheeling his belongings in a wheelbarrow from an adjoining State across Westralia to Coolgardie. He had a mate, but the mate knocked up on the road, and he put him and his swag on top of his own dunnage, and pushed the lot on to the goldfield. On the Crows' Nest track (Queensland), I came up to a man pulling a brandy-box on four wooden wheels. He had a good load on, which was covered over with a bag, and on top of that was coiled a tender-footed dog.

"Goreny grease on yer, mate?" he asked. "Th' bloomin' squeak o' this fakus is enough to give a cove th' blues."

I regretted I wasn't doing anything in that line, and he deplored the scarcity of goannas.

" 'F I could only drop across a ole gwana," he said, looking round at the forest of blackbutts, "I'd get enough axle-grease out of him ter do a week. It's not th' wear-an'-tear o' th' axles alone, but it's a devil's own drag when yer wheels ain't greased. Have ter make a do of it though, I s'pose. S'long!"

Coming down once from Glen Innes to Grafton, I passed two new chums carrying the most awkward-looking load one could imagine. Their property was contained in a chaff-bag, and hung by the middle across a pole which they carried on their shoulders, walking one behind the other. A billy-can and a kerosene tin (for boiling meat) also hung under the pole; and, while one carried a gingham, the other flourished a walking-stick and smoked cigars. They looked as though their mothers had just let them out for an airing.

Two terms that are often confounded one with the other are swagman and bagman. The first is a footman, the other a mounted man who may have anything from one to half a dozen horses. Though both are looking for work, they move on very different planes; the latter is considered a cut above the former, and looks down with a mildly contemptuous eye on the slowly-plodding swagman. They are rarely found in the one camp. If they both make a halt for the night at the same waterhole, they camp apart from each other, and, though one may visit the other's fire for a yarn, it is not as the meeting of two bagmen or two swagmen. Apart from the perennial quest of a job, they have little in common.

The bagman's main concern is grass and water. He is not always fortunate in getting both together. When he finds water there may be no picking there, and after watering his horses he has to ride on to feed, carrying a supply of water for himself. This is what a swagman calls a dry camp. The swagman can get sufficient water for his own consumption where the horseman cannot, as by rooting in the bed of a creek, by fishing down a well or a bore pipe with a tin and a few yards of string, from station dams and tanks, and other private reservoirs. He has no eye for grass; he doesn't know whether the way he has come is barren or rich in feed. Again, what he would term good feed the other might consider insufficient for a bandicoot, and vice versâ . At times the bagman is led off a good road on to a starvation track by the misresentations of the swagman; his horses suffer consequence, and the gulf between them widens. On the other hand, a brother bagman can not only accurately locate the good patches, but describe the different kinds of grasses and herbage along the road. This is probably the most potent reason why the bagman dissociates himself from the swagman.

But there are many more differences between them. Apart from the fact that a horseman appears to greater advantage, can dress better, and can keep clean, he hasn't to work hard in looking for work, and can represent himself as a stockman or drover, or even a cattle-buyer, while there can be no mystery about a swagman; affect what airs he likes, he can't disguise what he obviously is—a hard-up worker. Though there is little difference on a long journey in the daily stages made by each, the horseman travels faster, and may not occupy more than half the time in going from camp to camp. But he always has a horse-hunt to do in the mornings, and if his horses are ramblers, he has often to walk the equivalent of a day's journey in search of them before he starts, whereas the swagman has simply to roll up and strike straight away for the next station. The bagman, also, is listening half the night for his bell, or he is troubling over a lame foot, a swelled fetlock, or a sore back, while the swagman has nothing to disturb his night's rest if he has not inadvertently spread out his blankets on an ant's nest.

At times one finds the bagman and the swagman merged in one, forming a link between the two classes. Two mates have a horse between them, upon which they pack their belongings. They walk themselves, either leading the loaded animal in turn or driving him before them. Sometimes he becomes cantankerous when being thus driven, and bolts, scattering the pack along the road. As a rule, he is a quiet old moke, rough and hardy, who plods resignedly along with halfshut eyes, and sometimes goes to sleep altogether, dreaming of the sweet, wild days before he was a slave horse—of evergreen runs and perennial springs. He is an excellent judge of distance, and when he considers he has done about the usual day's stage he begins to look about for a camping-place, turning off at a clump of trees or making a bee-line for any depression in the landscape that has the semblance of a waterhole. If his wishes are disregarded for long, he is likely to zigzag about, particularly where there is any growing timber where the limbs might bump the pack off him. His eyes show annoyance; he begins to sulk, and his lip seems to hang lower than usual. If he happens to be far in front, he will probably lie down and roll, crunching up the billy-cans and doing other damage before he can be reached; and another favourite trick of his, if not closely watched on reaching a waterhole, is to give the objectionable pack a mud-and-water bath. He has learnt many dodges in his travels.

Of one-horse men there are two classes. One packs his horse and walks himself, in the same fashion as the mates. His horse is mostly too tired to take liberties, being a cheap old screw that takes six months to fatten and gets dog poor in a week, and it is owned by a man who is more used to walking than riding, but who objects to making a beast of burden of himself. The other man packs his horse and rides him too. When he is mounted you can see little more than the head, legs, and tail of his animal. He has a small swag strapped in front, but most of his dunnage is carried in a wallet thrown across behind the saddle. His quart-pot and meatbilly hang at the sides, his water-bag is suspended against the horse's chest, and the bell and hobbles are strapped round its neck. The animal is often a sturdy half-draught, more common in a spring cart than on a cattle camp. It is never put out of a walk, and is almost as omnivorous as the goat of backblock towns. If grass, herbage, or other fodder is unprocurable, it shares the owner's damper; in fact, it would leave its natural food for a few mouthfuls of dry damper or bread, and it thrives well on the diet. The footman, when he has got his ration bag dusted, solicits scrag ends of meat for his dog, but the one-horse man asks for any pieces of stale bread that may be on hand as a treat for the moke.

The bagman proper has at least two horses; one he uses as a hack and the other as a packer. He may be a shearer, drover, rouseabout, or general bush worker, and has usually a very fair turnout. The bagman is mostly without pack-bags, and the pack-saddle is often an old riding saddle (sometimes an overlander), the pack being rolled into a long bundle, and laid across the seat, and strapped down to the sides. His billy-cans, which are mostly rugged, are strapped on top, and ordinary paraphernalia are distributed about on the encircling straps. His equipment comprises a yard or two of oilcloth as an outside covering for his pack and foundation for his nap, a small tent or fly, a tomahawk, a gun or rifle, and sometimes a dish. He shoes his own horses, and is provided with a good shoeing tackle for the purpose. In districts where flies are bad his horses are fitted with leather protectors or netted veils. One of these animals is sometimes a cutter—a racehorse in disguise; and at stations, wayside pubs, drovers' camps, and shearing sheds he occasionally pulls off a match for a pound or a fiver. His best fields are the little towns. The town swell ridicules the idea of his flash hack being put down by the "old pack-horse," so a match is easily made, and side wagers laid as well. The packer, looking his roughest for the occasion, and moving slowly and sleepily about, becomes suddenly electrified on facing the starter, and to the surprise of everybody streaks away to the front like a second Carbine. But the owner doesn't call him Carbine; he calls him Mulga Bill, or something equally appropriate.

He contrives to be handy for the grass-fed races, and having knocked about the neighbourhood for a while and got his harmless-looking pair known to the officials (who are publicans and storekeepers), and having entered them when apparently drunk, he is rewarded for his trouble by getting Mulga Bill light-weighted for the Kookooboorara Jockey Club Handicap. Then he goes a few miles out and assiduously trains Bill for the event. When the regulations require Bill to be imprisoned in the club's paddock for a week or two, he is trained by moonlight along the main stock route, and has the nosebag slipped on him in quiet corners. Bill is used to substitutes and rough preparations, and very often springs a surprise on the public when the races come off.

There is also the man with the spare horse, which might be anything from an encumbrance to a flyer—mostly an encumbrance. He either drives it and the pack-horse before him, or leads the packer and lets the spare nag follow. It is useful at times; it comes handy to ride up to town while the others are spelling, but it is, nevertheless, a nuisance. It is always running off the road to feed, or to get a drink; it turns down the creeks and gullies, and trots over to any strange horses that appear. When it is being driven it reaches the gates first, and turns down the fence, and when it is following it is usually a mile behind when the gate is reached, and there is either a long wait or the owner has to go after it. It is often a colt and is broken in on the road to carry a pack, and generally succeeds in breaking up the pack during the process. The man, if he has no money and desires to tap the stations for rations, takes the precaution to hide his stock, and goes up to the homestead on foot, perhaps carrying a readied-up swag and specially dressed for the occasion. When he has got his supply he makes a wide detour to escape observation, and turns out where his bells won't be heard by the station people.

Some men travel with several horses, all of the average stamp of station hacks. There are usually one or two flighty ones among them, but the majority are quiet and staunch. These travellers are cattle-men, scalpers, brumby-hunters, buffalo-shooters, or prosperous diggers. They have first-class riding gear, perhaps a couple of pack-saddles each, with complete fittings. They pay their way wherever they go, and never stoop to cadging at stations. Some of them employ a black boy (or a black woman dressed as a boy) to look after the horses. This is common in the west and north-west of Queensland. Travelling to them is like a holiday, and when several meet in a camp they enjoy a merry evening. The packs will produce two or three different musical instruments, and music, songs, recitations, and yarning alternate till late at night, while a dozen horse-bells are jingling in the bush around them. Finally, there are those who travel about with buggy and pair, in wagonettes, light spring carts, tilted carts, spiders, sulkies, and other traps (not to mention the huge contingent spinning around on bikes). These are mostly big-gun shearers, shearers' cooks, drovers, and bush contractors. Most of them, as a rule, have a definite destination, while the other travellers seldom know where they are going to pull up. No notice is taken of even rouseabouts driving up to a shed in spanking turn-outs at shearing-time, and asking for a job in starched shirts and stand-up collars; but if one clattered up in his buggy at other times and asked for ordinary station work, he would be regarded as an escaped lunatic. So the buggy, like the bike and the horse, must be planted among the bushes.

No utensil is so generally used in the bush as the billy-can; none is more widely distributed, none better known in Australia. It is cheap, light, useful, and a burden to no man. It goes with every traveller, it figures in comedy and tragedy, and has been the repository of the last words of many a perished swagman. Often it is found with the grim message scratched on the bottom, beside the dead owner.

Billy is famous. Story-writers and poets have immortalised him; he figures proudly in a hundred tales, in a thousand poems.

He seems to have originated on the Victorian goldfields. The early miners consumed great quantities of French tinned soup, called bouilli; and the empty bouilli-cans were used for the same purposes as are now the specially made "billy-cans." Quart-pots, jackshays, pannikins, and other relatives followed as a matter of course.

For a horseman or cyclist on a short journey, who has no cooking to do, the quart-pot is the handier. But where there is one quart-pot in the bush there are ten billy-cans. The billy is carried in all manner of hands—black, white, yellow, and brindle. Shearers, miners, drovers, knockabouts, and even the poorest deadbeats on the track, carry it a-swing at their sides. It is swung under wagons, bullock-drays, hawkers' vans—every kind of vehicle that traverses the bush; and it jingles a tune to the Afghan from the back of his camel. The dainty housewife in town not infrequently sets it on her polished stove, and it often takes the place of the kettle in the cooky's home. Go into any aboriginal camp in the bush, and you will see billy-cans there, but seldom any other utensils. All classes of people, whether city dwellers or backblockers, take it along with them when they go picnicking. There is scarcely a camp or hut in Australia without one, and some have a dozen. And what an array they would make if they were all stood in line! There would be a hundred miles of billy-cans! And the quarts and pannikins that are carried about would build a mountain.

Every traveller has a pannikin or two and one or two billies. Some have three—of varying sizes to fit one in the other. The tea-billy and meat-billy are the most common; the third is an auxiliary. Some swagmen have a special water-billy, carried in the hand, with a tightly-fitting bag drawn over it to keep it cool. The bag also prevents the footman's trousers being blackened from contact and the horseman's pack from being soiled. This is called a rugged billy.

A simple way of keeping liquid cool in a billy-can is to put the lid on upside down and fill it with water.

Billies are of all sizes—from one to six quarts. The most favoured are the two-quart for tea, and four-quart for meat; while the general all-round billy is the three-quart size. I have seen many a hard-up swagman with an improvised billy made from a fruit-tin, with a bit of fencing wire for handle. This is known as a "Whitely King," from the fact that the Secretary of the Pastoralists' Union, during a shearers' strike, sent out a band of non-unionists furnished with this kind of utensil. They are therefore despised by bushmen.

Most travellers are particular as to how they boil their billies, for carelessness means waste of time and injury to the billy. The old style was to put a fork at each side of the fire, with a pole across to hang the billy from. The tripod answered the same purpose. Another method was to put two logs closely together so that the billy would stand on them—which left very little room for the fire. Some used a long pole resting on a fork, with the small end over the fire and the butt weighted on the ground. In using this the traveller had to be careful to keep his blaze down, or the pole would burn through.

No such clumsy, time-wasting methods are employed to-day—except at fixed camps, where the forks and cross-piece are put up, and a chain or looped wire for hooks hung therefrom. The traveller places two small sticks on the ground with the ends in the fire, or rakes out a few coals and stands the billy on them, close to the fire. He doesn't build a fire round it or jam it against the wood. The new chum does that, and his billy has a bright, shiny glow. This is caused by hot, vapoury smoke, the result of leaving insufficient air-space, One notices, too, that the old hand fills his billy to the brim, while the inexperienced man often puts his billy to the fire only partially filled, and consequently the rim, being unprotected, is very soon burnt off. A half-filled billy should never be placed against a fire, but stood or hung over it. The old hand, again, lifts his quart from the fire, and can carry it a long distance, with two sticks thrust crosswise through the handle so that the ends grip the sides like a pair of tongs. It looks simple, but it requires practice. When he has a smoky fire he lays two sticks across the top of the can to keep out the smoke.

An old whaler was once camped on the Severn River, living on fish. He had only one billy. He first made his tea in it, which he poured into a pannikin, then boiled his fish in it. He also had a small block of wood the same size as the billy, on which he sat and smoked. One evening at dusk he came up from the river with a tomahawk in his hand, and making for what he took to be the block, stuck the tommy into it. A yell of dismay escaped the old fellow when he found he had driven it through the bottom of his billy. Yet, with a piece of calico through the gap, and the edges battered down, he used it for months after. Another member of the battling band found a rusty billy, half embedded in mud, at the edge of a waterhole. It was full of water, and on forcing the lid off, he found a fish, about a pound weight, scurrying around in it. It was shaped like a boomerang, and had undoubtedly got in through a small aperture in the lid when very young. That billy, probably, performed its last duty when it boiled its life-long prisoner.

Among some travellers billy-boiling takes the form of a competition. The man of experience, looking over an array of well-used billies, says: "I'll back my billy to boil first." Interest being thus awakened, the others then put fiery spurs to their own utensils, each waiting, with tea-bag in hand, for the first ripple. Of course, some are specially adapted for quick boiling, whilst others are "naturally slow." A man with a quick boiler is always ready to back it against any other. He understands it, and can judge its boiling-time to within a few seconds. An old billy will boil quicker than a new one. The water is also worth considering. River-water will boil quicker than rain-water, stagnant water quicker than running water, whilst water that has once been boiled and cooled will boil again quicker than any other.

Yet, there is many a tedious wait for the billy to boil, and rejoicing of hungry ones when it begins to bubble. The old diggers on Ballarat and Bendigo used to sing, "Oh, what would you do if the billy boiled over?" when it was time to make the tea. And what legends are wrapped around the billy! Yarns are always being told, and bush songs are always being sung around a million camp fires while the billy boils.