«

back to Gabor Terebess

«

back to Terebess Online

Gabor

Terebess

JAPANESE RAKU AND ITS AMERICAN RENAISSANCE

German

version

Hungarian version

(Művészet, XXIII. évfolyam, 9.

szám, 1982. szeptember, 12-14. oldal)

"But

we have this treasure in earthen vessels, that the excellency of the power may

be of God, and not of us."

King James Bible [2 Corinthians 4:7]

"Touch

with your hands what your eyes suggest"

Attila József

A

surprising thing took place some years ago when Raku XIV. (楽, otherwise known as 覚入 Kakunyū, 1918-1980)

requested that several museums return to him the collection of tea bowls he had

previously lent to them for an unlimited period of time. His reason was the following:

Raku tea bowls become ruined if they are not used. Removing a cold and dry Raku

from a museum showcase and holding it in one's hands would indeed cause exasperation,

especially for those whose fingers and lips have experienced the intimate warmth

and wetness of a tea ceremony. Should any readers feel embarrassed, let me remind

them of the modern repulsion for touch which Philip Rawson (1924–1995) calls "tactile castration".

In fact, I could most easily compare the artistic delight offered by a Raku bowl

to that of a sexual encounter; the ritual act of stroking and caressing a human

figure. All of this happens in a completely natural way when using a Raku tea

bowl - fondling a statue or brushing one's lips to an art object would only give

the impression of deviant behaviour.

Over four-hundred years old, Japanese Raku ceramics (楽焼 raku-yaki) have been linked to the tea ceremony from the very beginning. The first Raku tea bowls (楽茶碗 rakuchawan) were created in Kyoto at the impetus of Sen no Rikyū (千利休, 1522-1591) in the late 1570s or the early 1580s by a maker of roof-tiles called Chōjiro. Their relationship can not be regarded in modern terms as that of designer and contractor, but rather as a rare meeting between critic and artist. Having discovered the raw power and exceptional sculpting talents of the potter, the tea master was given a long-awaited opportunity to replace his increasingly expensive, imported Chinese (唐物 karamono) and Korean pottery (高麗茶碗 kōrai chawan) with pieces created at home (国焼 kuniyaki) and specifically designed for the tea ceremony.

|

Shunkan 俊寛 |

Omokage 面影 |

Jirōbō 次郎坊 |

Ōguro 大黒 |

Jirōbō 二郎坊 |

Yūgure 夕暮 |

Dōjōji 道成寺 |

|

|

Ichimonji 一文字 |

Muichi-motsu 無一物 |

Tsutsumi-gaki つつみ柿 |

Hayafune 早船 |

Kōtō 勾当 |

Kamiyaguro 紙屋黒 |

Tōyōbō 東陽坊 |

Hijiri 聖 |

Chōjiro's Tea Bowls

Sen no Rikyū, aesthete and tea master in the court of Toyotomi Hideyoshi (豊臣秀吉 (1536-1598), reigning shogun, was a remarkable servant and brilliant model for the tastes of his age. He succeeded in finding the common denominator between the pure, Spartan creed of a military dictatorship (supported by a secularised Zen Buddhism) and the luxurious demands of samurai knights, new-fledged officials and prospering merchants. The "wabi-cha" (侘茶) - as the Rikyū tea ceremony is called - is the shrewd art of subtle simplicity, intentional contingency and invented naturalness. The objects used are seemingly rough, barren and deficient, but their realisation comes about with the greatest of care and craftsmanship.

The ceremony itself comprises nothing autonomous; it is a synthesis of traditional Japanese arts in which everything is applied and everything is interdependent. As is frequently the case with oriental art, it is not only the dividing line between fine art and industrial art that is blurred, but also that of religion, philosophy, etiquette, dress and nutrition. The ritual is evidence of the fact that life and art are indivisible and integrated. Nevertheless, the practice still takes place detached from daily life, in separate tea gardens and tea rooms, with utensils selected specifically for this purpose and in strict accordance with Zen taste.

A tile-maker by trade, Chōjiro never learned how to throw on a potter's wheel, using leather hard clay to carve his "sculptures from which tea can be drunk". He could only heat his primitive kiln at a low temperature and tried to take maximum advantage of the small combustion chamber by not "leaving the bowl to cool in the chamber" (焼冷まし yakizamashi), instead using a pair of wrought-iron tongs to "remove it hot" (挟み出し hasami-dashi) and immediately replacing it with another. Red Raku (赤楽 aka raku) was allowed to cool in the open air, while black Raku (黒楽 kuro raku) was quickly dipped in lukewarm water. Chōjiro favoured these two colours in his work. Red was obtained by applying several layers of transparent glaze to the damp, ochre soil which served as the basic material while black could be produced by grinding pebbles with a high content of iron and manganese, gleaned from the Kamo river (鴨川 Kamo-gawa), the main waterway cutting across Kyoto. This was the process which gave birth to Raku, meaning freely sculpted ceramics, glazed and fired at low heat, and abruptly vitrified. This would seem a step backwards in terms of the technical standard of the time. Since the Nara period (8th century), potters in even the most remote of Japanese villages had long been firing ceramics at temperatures of more than 1200 °C, although porous, low-fire ceramics could perform their function just as well. The water in an earthenware jug is kept fresh because it is able to permeate and evaporate over a large surface. A an earthenware cooking pot does not crack on an open fire since its soft wall diminishes the stress produced by being heated on one side. Being a poor conductor of heat, a Raku bowl keeps tea warm during a lengthy ceremony without becoming too hot to hold (it has no handles and must be cradled with both hands). When hit, it must produce a dull sound - the loud clink of the bamboo tea whisk (茶筌 chasen) would otherwise disturb the peace of the ritual.

The name Raku comes from Hideyoshi shogun himself. Following Chōjiro's death, he gave his adopted son Jokei (常慶, 1561-1635) a golden seal containing the written symbol "Raku" (楽). Literally translated, the sign means "the joy of leisure time". Jokei was also honoured with the name "Tenka no ichi 天下一" (the best under the Heavens) and his descendants have also used 'Raku' as their family name since then. After the Meiji period, the original family name of Tanaka (田中) was permanently abolished in favour of Raku (楽).

The workshops of the Raku family in Kyoto are called hon-gama(本窯); the official kilns where only one master works at a time until his heir or adopted son takes charge.

|

Amagumo 雨雲 |

Kaga Kōetsu 加賀 光悦 |

Shichiri 七里 |

Fuji-san 不二山 |

Kansetsu 冠雪 |

Azuma 東 |

Seppen 雪片 |

Murakumo 村雲 |

|

Jukushi 熟柿 |

Otogoze 乙御前 |

Kamiya 紙屋 |

Seppō 雪峯 |

Bishamondō 毘沙門堂 |

Minegumo 峯雲 |

Suiō 水翁 |

Shigure 時雨 |

Kōetsu's Tea Bowls

Kenzan's Tea Bowls

Other Raku ceramics are made in waki-gama (脇窯); auxiliary workshops; all other productions, whether Japanese or foreign, past or present, belong to betsu-gama (別窯 literally "other fires"). In addition to Chōjiro, Hon'ami Kōetsu (本阿弥光悦, 1658-1637) and Ogata Kenzan (尾形乾山, 1663-1743), the two greatest masters of Japanese Raku ceramics, both worked in waki-gama. While the "touchable" works of Chōjiro reflect a reserved visual quality not unlike that of sanded river pebbles, the decorative brushwork, unique sense of colour and ingenious composition evident in the work of Kenzan are primarily meant for the eyes rather than the hands. Among the three artists, it was Kōetsu who managed to find the golden mean between visual and tactile quality. Descended from a family of sword experts, he only dealt with ceramics on an amateur level, much as he did with the arts of lacquering and calligraphy. Although only seventeen bowls can definitely be attributed to him, they provide reason enough to regard him as one of the greatest ceramists of all time. Kōetsu never produced pieces on commission, preferring to create only for pleasure. No two of his works are alike; none of them have the same shape or adhere to a set stereotype. His most beautiful piece is called Fuji-san (不二山), known alternatively as Furisode chawan (振袖茶碗); the bowl was the only dowry that his daughter brought into her marriage from her father's house. She carried it wrapped in the sleeve (furisode) of her kimono.

The ceramists of Kyoto were the first in the history of Japanese ceramics to become renowned artists as opposed to remaining anonymous craftsmen. In fact, certain pieces among their works are referred to by name. Two of Chōjiro's most exceptional works are called Ōguro (大黒) - "Big Black", and Hayabune (早船) - "Fast Ship". In addition to the aforementioned Mt. Fuji, Kōetsu's collection also includes Amagumo (雨雲) - "Rain Cloud", Seppō (雪峯) - "Snow Peaks ", and Jukushi (熟柿) - "Ripe Persimmon".

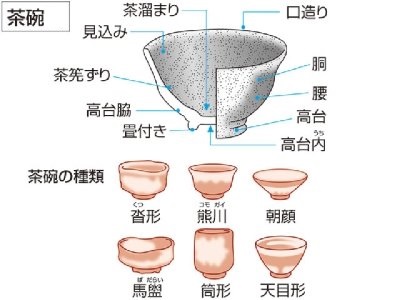

How to describe a typical Raku tea bowl? Firstly, it is used exclusively for the ceremonial drinking of tea, never for anything else. It has no handles, but always has a foot ring on its underside. It must never be filled to the brim with hot tea. It is held at its two coolest points; at its lip (口造り kuchizukuri) with the right hand and at its base-ring (高台 kōdai) with the left. Its average diameter is 8-15 cm, but 10-13 is more common. Its asymmetrical (不均整 fukinsei) balance is achieved by hand-carving (手捏ね tezukune). From a visual aspect, it can not be reproduced; it is a stranger to the reliable geometry of the potter's wheel. Its lip is characterised by soft and uneven waves, usually comprised of 3-7 "hills" (岳 gaku). Its plain, rounded form conforms well to the hands holding it. There are no sharp edges. It must not only sit comfortably when held, but must also stand firmly on the tatami (畳付き tatamitsuki) since the fear of possible spillage would disturb the ceremony. The inside of the bowl contains a spiral indentation running down to the lowest point of the bottom so as to collect the last drops of tea, called "tea pool" (茶溜り cha-damari), they may gather as naturally as rainwater in the depression of a rock. A slight crest runs along the inner edge of the lip to prevent the tea from being splattered when stirred by the bamboo whisk. This line is broken at the point where the tea is sipped, allowing the liquid to flow smoothly into the mouth of the drinker. Upon receiving the tea bowl from the tea master, the guest must turn the bowl in order to drink from it, which gives the person an opportunity to look at the "landscape" (keshiki 景色) and to caress the fine modulations on the alternately rough and smooth surface of the bowl (tedori 手捕り).

The colour of the tea bowl can only be appreciated when the cup is full; its true beauty is experienced through its use. The most common glazes to be found are red (赤楽 aka raku) or black (黒楽 kuro raku), although we may sometimes encounter white (白楽 shiro raku), or the occasional green (青楽 ao raku). The beauty of the tea bowl depends not only on the tea, however, but also on the wood, paper and straw environment of the tea room itself. Stone walls and glass windows are not an appropriate setting. Winter requires the use of taller cups narrowing at the brim as opposed to the flatter, wider variety used in the summer.

Japanese Raku bowls project no tactile or visual illusions. They are as warm to the touch as they are to the naked eye. Their material is porous and light, producing a dull sound when tapped by a fingernail. They both look and feel damp. Their smooth and pleasant surfaces are broken only by a few decorative brush strokes located opposite the drinking point - if any such decoration is to be found at all - and the sharp "wounds" left by the iron tongs. There is no opportunity to correct either of these marks; they are a permanent evidence of singular and determined motion. During the cooling process, while the glaze is still in a liquid state, it hangs on the surface of the bowl like a "wet rag" (幕薬 maku gusuri), or in "running drops" (流 nagare), stiffening into a fine weave of hairline cracks. There is no such thing as a faultless glaze on a Raku bowl. Indeed, the perfection achieved in the quality-control of mass-produced ceramic ware is foreign to Raku. The randomness of Raku glaze is not the result of an invented and refined method, but is simply the natural consequence of the glazing technique. Since the technique accepts human limitation, it is open to unintentional mistakes. Though a Raku bowl may seem rough and cumbersome when compared to something as refined as a rococo tea cup, for example, it nevertheless possesses an undeniable hidden refinement which far surpasses that of its cousins. Its form is methodically "worked" as opposed to being designed. When the Raku master opens his red-hot kiln, he has only seconds to act in harmony with the "heat of the moment." Once the glaze has stiffened, the artist has no time to consider what he has done or what he might do - there is no past or future. He must act fully in the present. Making corrections is a pointless endeavour as the bowl has already cooled, hence the master is open to any result, be it ordinary or unique. He accepts the consequences of the moment and forgets what has already passed. Not unlike a smoothly flowing river, he acts without hesitation; neither turning back, nor rushing forward. His goal is not to perfect the technique, but to experience it. "He doesn't know what he has conceived until he sees it". His discipline is entirely different from that required in the process of professional design and implementation. "He behaves like water, his calmness a mirror and his answer an echo."

Leach: Red Raku

Bowls (St. Ives, c. 1920-1925), The first piece has been broken and repaired, using gold

lustre to accentuate the damage in the same manner as early Japanese raku potters.

The first news of Raku ceramics to appear in Europe originates from the English ceramist Bernard Leach (1887-1979), who learned the technique from the descendants of the Raku family, and who was awarded the right to use the seal. In spite of this, Leach soon gave up using the technique, not really knowing what to do with it.

At the end of the 1950s, the American Paul Soldner (1921-2011) decided to try the Raku technique with his students based on information from Bernard Leach's book entitled "A Potter's Book". Following several failed attempts, Soldner hit upon the idea of wrapping the hot bowl in dry leaves directly after removing it from the kiln, and prior to dipping it in water. The reduction that occurred as a result was the beginning of the triumphal march of Raku in America.Until then, the glaze on a Japanese Raku bowl had never come into contact with any inflammable material. The surface was broken only on the spot where it had been held by tongs. The cracked and scorched surface of the American version was "instant antiquity", personified in the typically American nostalgia for antique objects, a phenomenon which is unimaginable in Europe. Moreover, it connects with a trend in ceramics that reflects a certain disgust for "space-age " technology, using primitive techniques to create ceramic objects in total rebellion against functionalism and symmetry.

American Raku is not an imitation of the Japanese, which is its main virtue as well as its primary limitation. Since it is not created to perform a specific function as in Japan, it utilises every means to attract attention to itself, turning away from the ostentatious visual effects found in its Japanese counterpart. While a Japanese Raku is regarded as timeless, the American version gives the impression of being somewhat obsolete, a characteristic which is well-suited to the consumer desire for artistic trends of the past - namely abstract expressionism. Japanese Raku is created using only one technique and material in a highly refined process, while American Raku is characterised by a confusing variety. The Raku of Japan is also acquainted with the discipline of nature; American Raku only senses its awkwardness. In its impatience for immediate results, Raku in America has neglected to notice the slow process of maturation that one Japanese master described as "having to become a certain person before being able to achieve certain things." For the American ceramist, the height of the experience is firing itself - the "big happening". His Japanese colleague experiences the "summit" in all elements of the process - "every day is a good day". Japanese Raku bowls seem a bit banal and uninteresting to the American eye, which regards them as being all the same and confined within strict limits. The American "Raku artist" has difficulty in understanding the refined power of limitation, the aesthetic value and barren dignity of suggestion, and the importance of achievement measured in terms of tradition. His desire for something new at all costs has resulted in a search for effects which are exciting, yet superficial. Primitive, tormented surfaces and the bright lustre produced by scarce nitrates and chlorides have intoxicated him. Special technical innovations (designer tongs, large-capacity kilns) have made it possible to create products of immense size, but without the unique simplicity and intimate peace found in Japanese Raku.

The Japanese tea ceremony is largely unknown here in Hungary, and from the standpoint of assessing teacups, our cult of ceramics can be described as rather primitive. On the other hand, we do not understand the American ceramists aversion to modern technology since we create ceramics out of need as opposed to rebellion. The trends of 16th century Japan and the 1960s in America seem equally strange to us. However, there have been some attempts to approach these trends. Both Imre Schrammel and Károly Szekeres have worked with the American style of Raku, and Ilona Benkő has won several international awards with her Raku statuettes. Using a salt glaze, American ceramists Kendra and David Davidson demonstrated the technique of utilising soda firing in the Raku process last year [1981] at the International Ceramics Symposium in Siklós, and there are sure to be Hungarian artists who will follow in their footsteps. Indeed, I myself have been exploring the possibilities of Japanese Raku both in theory and in practice for over ten years.

Gabor Terebess's Raku Tea Bowls

The place where the potter gripped the piece (while applying the glaze) is clearly seen in the finger impressions around the base; this is called 指痕 yubi-ato in Japanese. (Lit., "Finger remainder.")

Budapest, 1982.

The Raku Family

楽焼 Raku-yaki = Low-fired ceramic ware (軟質 nanshitsu = ”soft quality”) made in Kyoto by the Raku FamilyI. 長次郎 Chōjirō [?-1589]

II. 常慶 Jōkei [1561-1635]

III. 道入 Dōnyū [1599-1656]

IV. 一入 Ichinyū [1640-1696]

V. 宗入 Sōnyū [1664-1716]

VI. 左入 Sanyū [1685-1739]

VII. 長入 Chōnyū [1714-1770]

VIII. 得入 Tokunyū [1745-1774]

IX. 了入 Ryōnyū [1756-1834]

X. 旦入 Tannyū [1795-1854]

XI. 慶入 Keinyū [1817-1902]

XII. 弘入 Kōnyū [1857-1932]

XIII. 惺入 Seinyū [1887-1944]

XIV. 覚入 Kakunyū [1918-1980]

XV. 吉左衛門 Kichizaemon [1949-]

The genealogy of the Raku families (in Japanese)

Tea Bowl Parts

口造り kuchizukuri / lip

茶巾摺り chakinzure / contact area interaction with tea-cloth, a small oblong piece of plain white linen used to wipe the tea-bowl

茶筅摺り chasenzure / A chasen is a bamboo whisk used to stir the tea. This is the area of the tea bowl where the chasen would rub against the sides.

見込み mikomi / 'bottom', 'prospect'

茶溜り chadamari / 'tea pool'

口辺下 kuchiberishita / deflection below the lip

胴 dō / body

腹 koshi / hip

高台脇 kōdaiwaki / base outside the foot ring

高台際 kōdaigiwa / angle of base and foot ring

高台 kōdai / foot

高台内 kōdainai / inside of foot

兜巾 tokin / hill inside of foot

畳付き tatamitsuki / foot contact area interaction with tatami

Simpson, Penny, and Kanji Sodeoka. The Japanese pottery handbook: Tōgei handobukku. Tokyo: Kodansha, 1979.蛇の目高台 or or 普通高台 janome kōdai or futsū kōdai / snake's eye foot

輪高台 wa kōdai; 一重高台 ichijūkōdai / 'ring' foot

三日月高台 mikazuki kōdai / 'crescent moon' foot

兜巾 tokin kōdai / 'helmet' foot

二重高台 nijū kōdai / double foot

渦巻高台 uzumaki kōdai / 'whirlpool' foot

貝尻高台 kaijiri kōdai / 'spiral shell' foot

竹の節高台 takenofushi kōdai / 'bamboo node' foot

割高台 wari kōdai / split foot

割十文字高台 warijūmonji kōdai / four split foot

割一文字高台 wariichimonji kōdai / two split foot

撥高台 bachi kōdai / 'shamisen plectrum' foot

切高台 kiri kōdai / 'cut' foot

切十文字高台 kirijūmonji kōdai / cross cut foot

切一文字高台 kiriichimonji kōdai / bar cut foot

釘彫 高台 kugibori kōdai / 'nail carved' foot

縮緬高台 chirimen kōdai / 'crinkled cloth' footTypes of Foot (DOC)

Selected Literature in Japanese

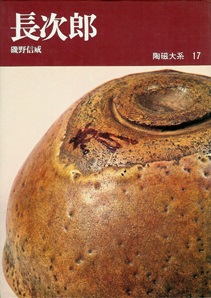

長次郎

http://kizuna-maboroshi.doorblog.jp/archives/23303279.html本阿弥光悦

http://kizuna-maboroshi.doorblog.jp/archives/35868890.html

http://otogoze.exblog.jp/陶器全集 Tōki zenshū [= Complete Collection of Ceramics]

東京 : 平凡社 Tōkyō : Heibonsha, 1960-1966. 32 vols.Vol. 6. 長次郎・光悦 (Chōjirō/Kōetsu by 磯野信威 Isono Nobutake, 1965)

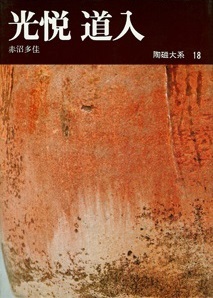

陶磁大系 Tōji taikei [= Complete Series of Ceramics]

東京 : 平凡社 Tōkyō : Heibonsha, 1972-1978. 48 vols.

陶磁大系第 17巻 二冊あり 特集長次郎 磯野信威 平凡社 昭 47 (Vol. 17. Chōjirō, 1972)

陶磁大系第 18巻 特集光悦道入 赤沼多佳 平凡社 昭 52 (Vol. 18. Kōetsu – Dōnyū, 1977)日本陶磁全集 Nippon tōji zenshū [= A Pageant of Japanese Ceramics]

東京 : 中央公論社 Tōkyō : Chūō Kōron-sha, 1975-1978. 30 Vols.Vol. 20. 長次郎 Chōjirō [by 林屋晴三 Hayashiya Seizō, 1928-]

Vol. 21. 楽代々・編集・解說 Raku daidai / henshū kaisetsu

Vol. 22. 光悦・玉水・大樋 Kōetsu, Tamamizu, Ōhi [by 林屋晴三 Hayashiya Seizō, 1928-]

Vol. 28. 乾山・古清水 Kenzan, Ko-Kiyomizu

Selected Literature in English

Leach, Bernard. A Potter's Book. London: Faber & Faber, 1940, 2nd ed. 1945, 3rd ed. 1975

Leach, Bernard. Kenzan and his Tradition, the Lives and Times of Koetsu, Sotasu, Korin, and Kenzan. London: Faber & Faber, 1966.Raku Handbook: A Practical Approach to the Ceramic Art by John Dickerson

Studio Vista, London, 1972.”Some Aspects of Raku Ware” by John Dickerson

Transactions of the Oriental Ceramics Society, 40, 1973-1975, pp. 20-30. 12 pls.Raku: Techniques for Contemporary Potters by Richard Hirsch and Christopher Tyler

Watson-Guptill Publications, 1975”Raku: The Beauty of Imperfection” by Gerd Lester

Arts of Asia, Jul-Aug 1991, 21(4): pp. 90-96.The Art of Ogata Kenzan: Persona and Production in Japanese Ceramics by Richard L. Wilson

Weatherhill, 1991.Raku: A Dynasty of Japanese Ceramists, edited by Hayashiya Seizō, Raku Kichizaemon (XV), and Akanuma Taka,

Catalog of an exhibition organized by the Raku Museum and the Japan Foundation, held at Museo internationale delle ceramiche, Faenza, Sept. 20-Nov. 9; at Maison de la culture du Japon à Paris, Nov. 20-Dec. 10; and at Keramiekmuseum het Princessehof, Leeuwarden, Dec. 19, 1997-Mar. 8, 1998.

The Japan Foundation, 1997, 219 p.The Arts of Hon'ami Koetsu: Japanese Renaissance Master by Dr. Felice Fischer, The Luther W. Brady Curator of Japanese Art and Acting Curator of East Asian Art, with Dr. Edwin A. Cranston, Dr. Fumiko E. Cranston, Ms. Kyoko Kinoshita, Kumakura Isao, Saito Takamasa, and Yamazaki Tsuyoshi

Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2000, 187 illustrations (142 color), 220 p.Tea Taste: Patronage and Collaboration among Tea Masters and Potters in Early Modern Japan by Morgan Pitelka

Early Modern Japan: An Interdisciplinary Journal. Fall-Winter, 2004, pp. 26-38.Handmade Culture: Raku Potters, Patrons, and Tea Practitioners in Japan by Morgan Pitelka

Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2005.

http://muse.jhu.edu/books/9780824862749Wrapping an Unwrapping Art: Introduction by Morgan Pitelka

In: What's the Use of Art? Asian Visual and Material Culture in Context, Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2008.Characterization od Japanese Raku Ceramics Using XRF and FTIR by Raina Chao, Blythe McCarthy, and Gail Yano

Glass and Ceramics Conservation 2010: interim meeting of the ICOM-CC Working Group, October 3-6, 2010, Corning, New York, U.S.A. / Hannelore Roemich, editorial coordinator, pp. 145-155.The Influence and Remaining Japanese Cultural Elements in Raku Artworks of Contemporary Non Japanese Artists/Potters

by Khairul Nizan Mohd Aris, The University of New South Wales, Australia 0417

The Asian Conference on Arts & Humanities, Official Conference Proceedings, Osaka, 2013.