Terebess

Asia Online (TAO)

Index

Home

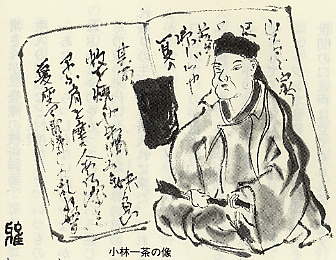

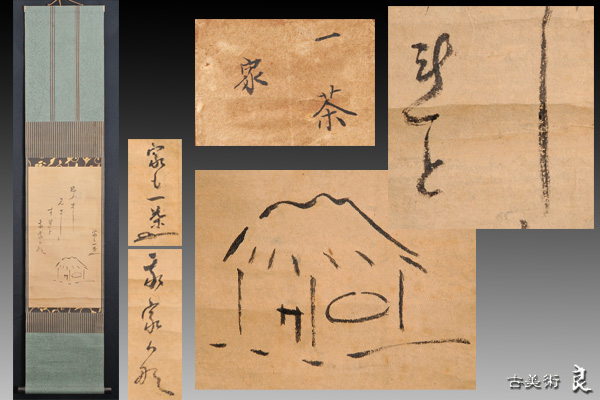

小林一茶 Kobayashi Issa

(1763-1828)

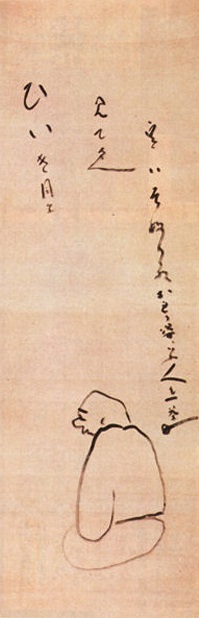

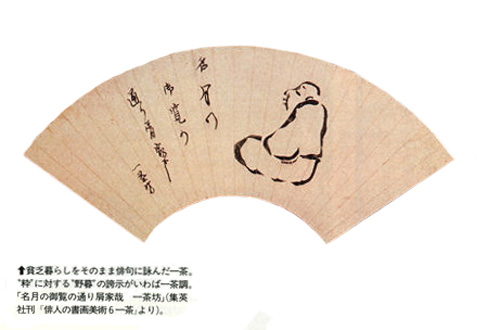

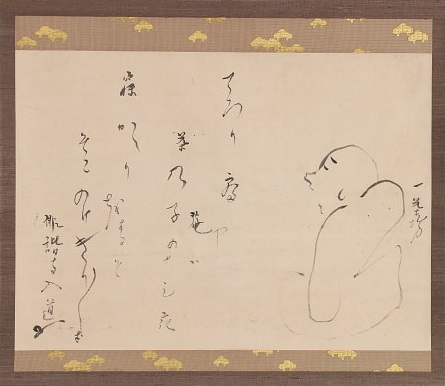

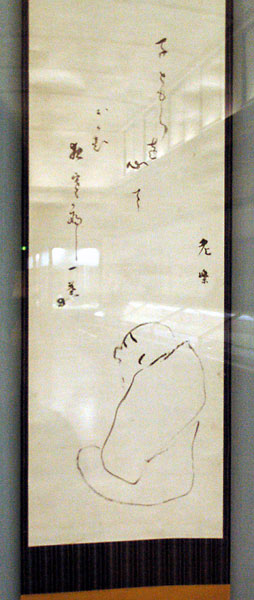

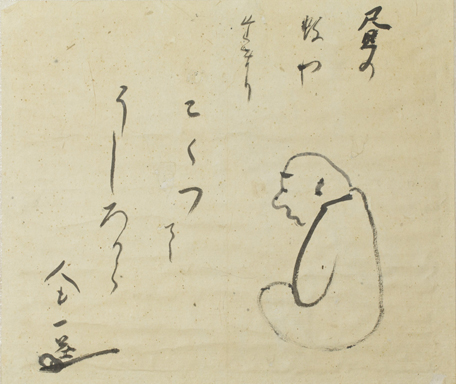

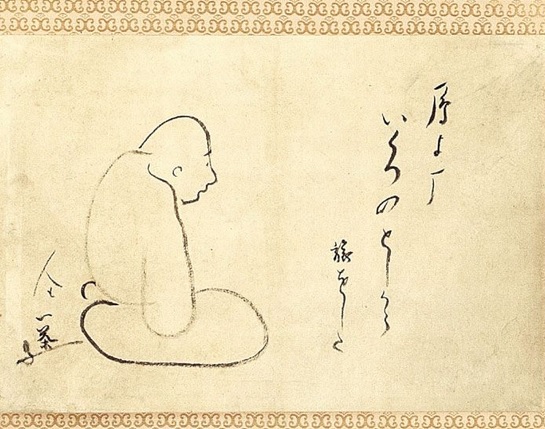

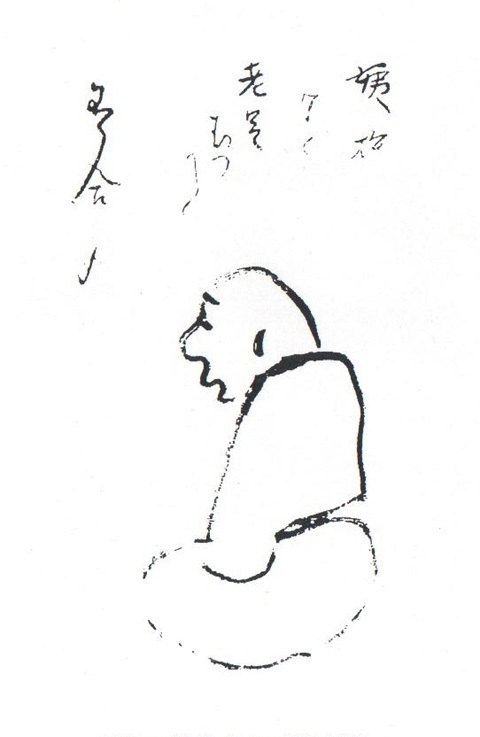

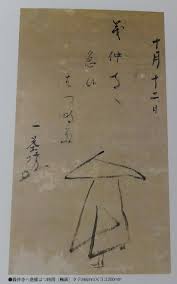

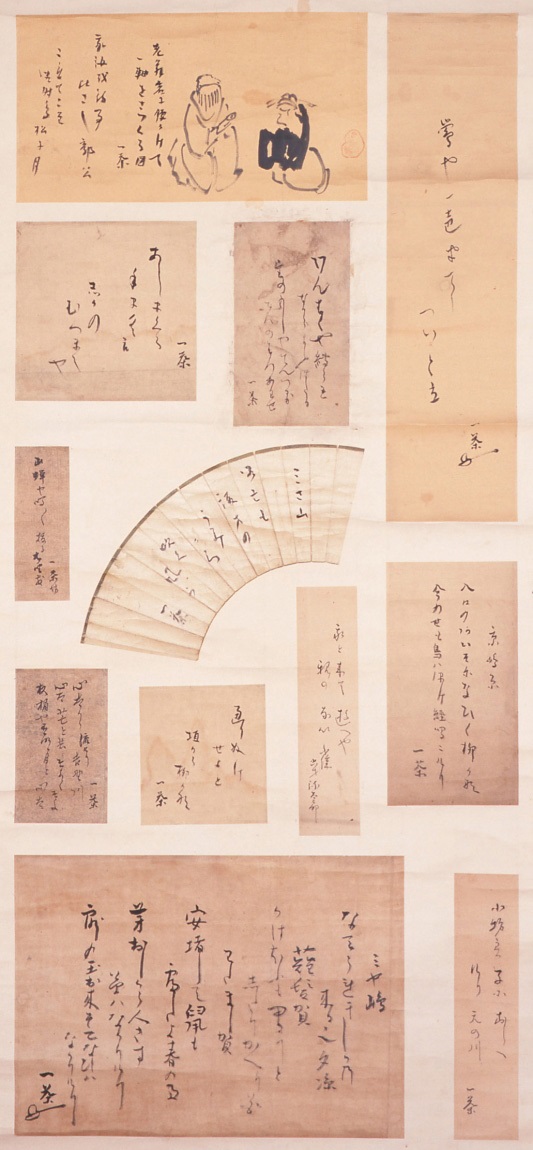

Self-caricature

Links:

![]() Japanese,

approx. 20,000 haiku online

Japanese,

approx. 20,000 haiku online

[The Complete haiku of Issa]:

http://www.janis.or.jp/users/kyodoshi/issaku.htm

![]()

![]() Japanese-English,

approx. 10,000 haiku online

Japanese-English,

approx. 10,000 haiku online

Haiku of Kobayashi

Issa by David

G. Lanoue

http://haikuguy.com/issa.html

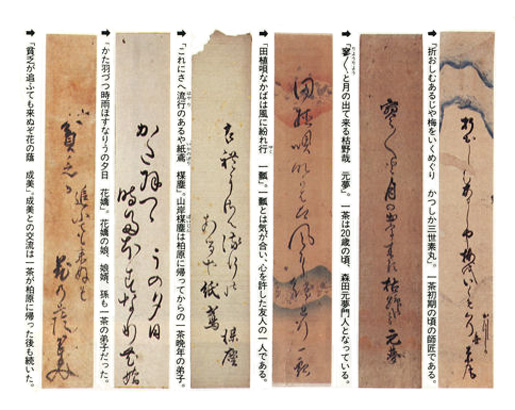

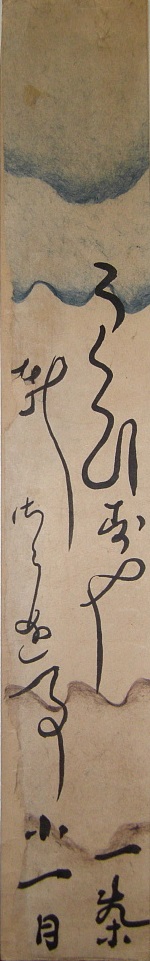

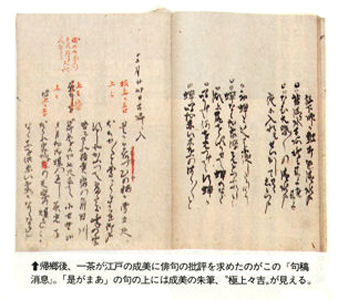

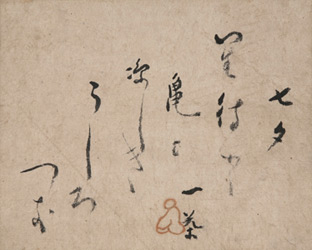

Calligraphic brushworks by Issa > ![]() PDF

PDF

![]() Terebess Gábor: Egy csésze tea Isszával, Orpheusz Kiadó, Budapest, 2000

Terebess Gábor: Egy csésze tea Isszával, Orpheusz Kiadó, Budapest, 2000

(429 haiku) > HTML > ![]() PDF

PDF

Issza magyarul: Bakos Ferenc, Barczikay Zoltán, Bozsik Péter, Cseh Károly, Deák László, Dombrády S. Géza & Szende Tamás, Faludy György, Gergely László, Greguss Sándor, Hamvas Béla, Horváth Ödön, Kányádi Sándor, Képes Géza, Kosztolányi Dezső, Kulcsár F. Imre, Legéndy Enikő, Miklós Pál, Naschitz Frigyes, Pető Tóth Károly, Pohl László, Rácz István, Szabolcsi Erzsébet, Tandori Dezső, Végh József, Veres Andrea, Zanin Csaba műfordításai.

![]()

![]() Terebess Gábor: Vissza Isszához

Terebess Gábor: Vissza Isszához

(603 haiku) > DOC > ![]() PDF

PDF

Although Issa is known primarily as one of the three great haiku poets, he also wrote prose-in Chichi no shûen nikki (1801; Diary of My Father's Death, 1992), a response to his father's death-and mixed prose and verse, or haibun, in Oragu haru (1819; The Year of My Life, 1960), an autobiographical account of his most memorable year.

Achievements

Ezra Pound's

recognition of the power of a single image which concentrates poetic attention

with enormous force and his examination of the complexity of the Japanese written

character led to an increasing awareness of the possibilities of haiku poetry

for Western readers in the early part of the twentieth century. Combined with

a growing interest in Oriental studies and philosophy, haiku offered an entrance

into Japanese concepts of existence concerning the relationship of man and the

natural world. Because the brevity of haiku is in such contrast to conventional

ideas of a complete poem in the Western tradition, however, only the most accomplished

haiku poets have been able to reach beyond the boundaries of their culture.

The most prominent among these are Bashô (1644-1694), Buson (1715-1783), and

Issa. As William Cohen describes him, "in humor and sympathy for all that

lives, Issa is unsurpassed in the history of Japanese literature and perhaps

even in world literature." A perpetual underdog who employed humor as an

instrument of endurance, who was exceptionally sensitive to the infinite subtlety

of the natural world, and who was incapable of acting with anything but extraordinary

decency, Issa wrote poetry that moves across the barriers of language and time

to capture the "wordless moment" when revelation is imminent. More

accessible than the magisterial Buson, less confident than the brilliant Bashô,

Issa expresses in his work the genius that is often hidden in the commonplace.

The definition of haiku as "simply what is happening in this place at this

moment" is an apt emblem for a poet who saw humans forever poised between

the timely and the timeless.

Biography

The poet known

as Issa was born Kobayashi Yatarô in 1763 in the village of Kashiwabara, a settlement

of approximately one hundred houses in the highlands of the province of Shinano.

The rugged beauty of the region, especially the gemlike Lake Nojiri two miles

east of the town, led to the development of a tourist community in the twentieth

century, but the harsh winter climate, with snowdrifts of more than ten feet

not uncommon, restricted growth in Issa's time. The area was still moderately

prosperous, however, because there was a central post office on the main highway

from the northwestern provinces to the capital city of Edo (now Tokyo). The

lord of the powerful Kaga clan maintained an official residence which he used

on his semiannual visits to the shogun in Edo, and a cultural center developed

around a theater which featured dramatic performances, wrestling exhibitions,

and poetry readings.

Issa was the son of a fairly prosperous farmer who supplemented his income by

providing horse-pack transportation for passengers and freight. His composition

of a "death-verse" suggests a high degree of literary awareness. In

the first of a series of domestic tragedies, Issa's mother died when he was

three, but his grandmother reared him with deep affection until Issa's father

remarried. Although his stepmother treated him well for two years, upon the

birth of her first child, she relegated Issa to a role as a subordinate. When

she suggested that a farmer's son did not need formal schooling, Issa was forced

to discontinue his study of reading and writing under a local master. When her

baby cried, she accused Issa of causing its pain and beat him so that he was

frequently marked with bruises.

According to legend, these unhappy circumstances inspired Issa's first poem.

At the age of nine or so, Issa was unable to join the local children at a village

festival because he did not have the new clothes the occasion required. Playing

by himself, he noticed a fledgling sparrow fallen from its nest. Observing it

with what would become a characteristic sympathy for nature's outcasts, he declared:

Come and play,

little orphan sparrow-

play with me!

The poem was probably written years later in reflection on the incident, but Issa displayed enough literary ability in his youth to attract the attention of the proprietor of the lord's residence, a man skilled in calligraphy and haiku poetry, who believed that Issa would be a good companion for his own son. He invited Issa to attend a school he operated in partnership with a scholar in Chinese studies who was also a haiku poet. Issa could attend the school only at night and on holidays-sometimes carrying his stepbrother on his back-when he was not compelled to assist with farm chores, but this did not prevent him from cultivating his literary inclinations. On one of the occasions when he was assisting his father by leading a passenger on a packhorse, the traveler ruminated on the name of a mountain that they were passing. "Black Princess! O Black Princess!" he repeated, looking at the snow-topped peak of Mount Kurohime. When Issa asked the man what he was doing, he replied that he was trying to compose an appropriate haiku for the setting. To the astonishment of the traveler, Issa proclaimed: "Black Princess is a bride-/ see her veiled in white."

Issa's studies were completely terminated when his grandmother died in 1776. At his stepmother's urgings, Issa was sent to Edo, thrown into a kind of exile in which he was expected to survive on his own. His life in the capital in his teenage years is a mystery, but in 1790 he was elected to a position at an academy of poetics, the Katsushika school. The school had been founded by a friend and admirer of Bashô who named it for Bashô's home, and although Issa undoubtedly had the ability to fulfill the expectations of his appointment, his innovative instincts clashed with the more traditional curriculum already in place at the school. In 1792, Issa voluntarily withdrew from the school, proclaiming himself Haikaiji Issa in a declaration of poetic independence. His literary signature literally translates as "Haikai Temple One-Tea." The title "Haikai Temple" signifies that he was a priest of haiku poetry (anticipating Allen Ginsberg's assertion "Poet is Priest!"), and as he wrote, "In as much as life is empty as a bubble which vanishes instantly, I will henceforth call myself Issa, or One Tea." In this way, he was likening his existence to the bubbles rising in a cup of tea-an appropriate image, considering the importance of the tea ceremony in Japanese cultural life.

During the next ten years, Issa traveled extensively, making pilgrimages to famous religious sites and prominent artistic seminars, staying with friends who shared his interest in poetry. His primary residence was in Fukagawa, where he earned a modest living by giving lessons in haikai, possibly assisted by enlightened patrons who appreciated his abilities. By the turn of the century, he had begun to establish a wider reputation and his prospects for artistic recognition were improving, but his father's final illness drew him home to offer comfort and support. His father died in 1801 and divided his estate equally between Issa and his half brother. When his stepmother contested the will, Issa was obliged to leave once again, and he spent the next thirteen years living in Edo while he attempted to convince the local authorities to carry out the provisions of his father's legacy. His frustrations are reflected in a poem he wrote during this time: "My old village calls-/ each time I come near,/ thorns in the blossom."

Finally, in 1813, Issa was able to take possession of his half of the property, and in April, 1814, he married a twenty-eight-year-old woman named Kiku, the daughter of a farmer in a neighboring village. Completely white-haired and nearly toothless, he still proclaimed that he "became a new man" in his fifties, and during the next few years, his wife gave birth to five children. Unfortunately, all of them died while still quite young. Using a familiar line of scripture that compares the evanescence of life to the morning dew as a point of origin, Issa expressed his sense of loss in one of his most famous and least translatable poems:

This dewdrop

world-

yet for dew drops

still, a dewdrop world

In May, 1823, Issa's wife died, but he remarried almost immediately. This marriage was not harmonious, and when the woman returned to her parent's home, Issa sent her a humorous verse as a declaration of divorce and as a statement of forgiveness. Perhaps for purposes of continuing his family, Issa married one more time in 1825, his bride this time a forty-six-year-old farmer's daughter. His wife was pregnant when Issa died in the autumn of 1828, and his only surviving child, Yata, was born after his death. Her survival enabled Issa's descendants to retain the property in his home village for which he had struggled during many of the years of his life.

In his last years, while he was settled in his old home, he achieved national fame as a haikai poet. His thoughts as a master were valued, and he held readings and seminars with pupils and colleagues. After recovering from a fairly serious illness in 1820, he adopted the additional title Soseibo, or "Revived Priest," indicating not only his position of respect as an artist and seer but also his resiliency and somewhat sardonic optimism. As a kind of summary of his career, he wrote a poem which legend attributes to his deathbed but which was probably given to a student to be published after his death. It describes the journey of a man from the washing bowl in which a new baby is cleansed to the ritual bath in which the body is prepared for burial: "Slippery words/ from bathtub to bathtub-/ just slippery words." The last poem Issa actually wrote was found under the pillow on the bed where he died. After his house had burned down in 1827, he and his wife lived in an adjoining storehouse with no windows and a leaky roof: "Gratitude for the snow/ on the bed quilt-/ it too is from Heaven." Issa used the word Jodo (Pure Land) for Heaven, a term which describes the Heaven of the Buddha Amida. Issa was a member of the largest Pure Land sect, the Shin, and he shared the sect's faith in the boundless love of the Buddha to redeem a world in which suffering and pain are frequent. His final poem is an assertion of that faith in typically bleak circumstances, and a final declaration of his capacity for finding beauty in the most unlikely situations.

Analysis

The haiku is a part of Japanese cultural life, aesthetic experience and philosophical expression. As Lafcadio Hearn noted, "Poetry in Japan is universal as air. It is felt by everybody." The haiku poem traditionally consists of three lines, arranged so that there are five, seven, and five syllables in the triplet. Although the "rules" governing its construction are not absolute, it has many conventions that contribute to its effectiveness. Generally, it has a central image, often from the natural world, frequently expressed as a part of a seasonal reference, and a "cutting word," or exclamation that states or implies the poet's reaction to what he sees. It is the ultimate compression of poetic energy and often draws its strength from the unusual juxtaposition of image and idea.

It is very difficult to translate haiku into English without losing or distorting some of the qualities which make it so uniquely interesting. English syllables are longer than Japanese jion (symbol sounds); some Japanese characters have no English equivalent, particularly since each separate "syllable" of a Japanese "word" may have additional levels of meaning; a literal rendering may miss the point while a more creative one may remake the poem so that the translator is a traitor to the original. As an example of the problems involved, one might consider the haiku Issa wrote about the temptations and disappointments of his visits to his hometown. The Japanese characters can be literally transcribed as follows:

Furosato ya

yoru mo sawaru mo bara-no-hana

(Old village : come-near also touch also thorn's-flowers)

The poem has been translated in at least four versions:

At my home everything

I touch is a bramble.

(Asataro Miyamori)

Everything I

touch

with tenderness alas

pricks like a bramble.

(Peter Beilenson)

The place where

I was born:

all I come to-all I touch-

blossoms of the thorn.

(Harold Henderson)

My old village

calls-

each time I come near,

thorns in the blossom.

(Leon Lewis)

Bashô's almost prophetic power and Buson's exceptional craftsmanship and control may be captured fairly effectively in English, but it is Issa's attitude toward his own life and the world that makes him perhaps the most completely understandable of the great Japanese poets. His rueful, gentle irony, turning on his own experiences, is his vehicle for conveying a warmly human outlook which is no less profound for its inclusive humor. Like his fellow masters of the haiku form, Issa was very closely attuned to the natural world, but for him, it had an immediacy and familiarity that balanced the cosmic dimensions of the universal phenomena which he observed. Recognizing human fragility, he developed a strong sense of identification with the smaller, weaker creatures of the world. His sympathetic response is combined with a sharp eye for their individual attributes and for subtle demonstrations of virtue and strength amid trying circumstances. Although Issa was interested in most of the standard measures of social success (family, property, recognition), his inability to accept dogma (religious or philosophical) or to overlook economic inequity led him to a position as a semipermanent outsider no matter how successful he might be.

Observer of Natural Phenomena

Typically, Issa

depicts himself as an observer in the midst of an extraordinary field of natural

phenomena. Like the Western Romantic poets of the nineteenth century, he uses

his own reactions as a measuring device and records the instinctive responses

of his poetic sensibility. There is a fusion of stance and subject, and the

man-made world of business and commerce occurs only as an intrusion, spoiling

the landscape. What matters is an eternal realm of continuing artistic revelation,

the permanent focus of humankind's contemplation: "From my tiny roof/ smooth

. . . soft . . ./ still-white snow/ melts in melody." The poet is involved

in the natural world through the action of a poetic intelligence which recreates

the world in words and images, and, more concretely, through the direct action

of his participation in its substance and shape: "Sun-melted snow . . ./

with my stick I guide/ this great dangerous river." Here, the perspective

ranges from the local and the minimal to the massively consequential, but in

his usual fashion, Issa's wry overestimation of his actions serves to illustrate

his realization of their limits. Similarly, he notes the magnified ambition

of another tiny figure: "An April shower . . ./ see that thirsty mouse/

lapping river Sumida." Amid the vast universe, man is much like a slight

animal. This perception is no cause for despair, though. An acceptance of limitations

with characteristic humor enables him to enjoy his minuscule place among the

infinities: "Now take this flea:/ He simply cannot jump . . ./ and I love

him for it."

Because he is aware of how insignificant and vulnerable all living creatures

are, Issa is able to invest their apparently comic antics with dignity: "The

night was hot . . ./ stripped to the waist/ the snail enjoyed the moonlight."

The strength of Issa's identification of the correspondence between the actions

of human beings and animals enables him to use familiar images of animal behavior

to comment on the pomposity and vanity of much human behavior. In this fashion,

his poems have some of the satirical edge of eighteenth century wit, but Issa

is much more amused than angry: "Elegant singer/ would you further favor

us/ with a dance, O Frog?" Or if anger is suggested, it is a sham to feign

control over something, because the underlying idea is essentially one of delighted

acceptance of common concerns: "Listen, all you fleas . . ./ you can come

on pilgrimage, o.k. . . ./ but then, off you git!" Beyond mock anger and

low comedy, Issa's poems about his participation in the way of the world often

express a spirit of contemplation leading to a feeling of awe. Even if the workings

of the natural world remain elusive, defying all real comprehension, there is

still a fascination in considering its mysterious complexity: "Rainy afternoon

. . ./ little daughter you will/ never teach that cat to dance."

Forbidding Nature

At other times, however, the landscape is more forbidding, devoid of the comfort provided by other creatures. Issa knew so many moments of disappointment that he could not restrain a projection of his sadness into the world: "Poor thin crescent/ shivering and twisted high/ in the bitter dark." For a man so closely attuned to nature's nuances, it is not surprising that nature would appear to echo his own concerns. When Issa felt the harsh facts of existence bearing heavily on him, he might have found some solace in seeing a reflection of his pain in the sky: "A three-day-old moon/ already warped and twisted/ by the bitter cold." Images of winter are frequent in Issa's poetry, an outgrowth of the geographical reality of his homeland but also an indication of his continuing consciousness of loss and discouragement. Without the abundant growth of the summer to provide pleasant if temporary distraction, the poet cannot escape from his condition: "In winter moonlight/ a clear look/ at my old hut . . . dilapidated." The view may be depressing but the "clear look" afforded by the light is valuable, and in some ways, reassuringly familiar, reminding the poet of his real legacy: "My old father too/looked long on these white mountains/ through lonely winters."

Home and Family

Issa spent much time trying to establish a true home in the land in which he was born because he had a strong sense of the importance of family continuity. He regarded the family as a source of strength in a contentious and competitive environment and wrote many poems about the misfortune of his own family situation. Some of his poems on this subject tend to be extremely sentimental, lacking his characteristic comic stance. The depth of his emotional involvement is emphasized by the stark pronouncement of his query: "Wild geese O wild geese/ were you little fellows too . . ./ when you flew from home?" These poems, however, are balanced by Issa's capacity for finding some unexpected reassurance that the struggle to be "home" is worthwhile: "Home again! What's this?/ My hesitant cherry tree/ deciding to bloom?" Although nothing spectacular happens, on his home ground, even the apparently mundane is dressed in glory: "In my native place/ there's this plant:/ As plain as grass but blooms like heaven." In an understated plea for placing something where it belongs, recalling his ten-year struggle to win a share of his father's property, he declares how he would dispense justice: "Hereby I assign in perpetuity to wit:/ To this wren/ this fence." For Issa, the natural order of things is superior to that of society.

The uncertainty of his position with respect to his family (and his ancestors) made the concept of home ground especially important for Issa as a fixed coordinate in a chaotic universe. His early rejection by his stepmother was an important event in the development of an outlook that counted uncertainty as a given, but his sense of the transitory nature of existence is a part of a very basic strain of Japanese philosophy. The tangible intermixed with the intangible is the subject of many of his poems: "The first firefly . . ./ but he got away and I-/ air in my fingers." A small airborne creature, a figure for both light and flight, is glimpsed but not caught and held. What is seen, discernible, is rarely seen for long and never permanently fixed. The man who reaches for the elusive particle of energy is like the artist who reaches for the stuff of inspiration, like any person trying to grasp the animating fire of the cosmos. The discrepancy between the immutable facts of existence and the momentary, incredible beauty of life at its most moving is a familiar feature of Issa's work: "Autumn breezes shake/ the scarlet flowers my poor child/ could not wait to pick." Issa's famous "Dewdrop" haiku was also the result of the loss of one of his children, but in this poem too, it is the moment of special feeling that is as celebrated-a mixture of sadness and extraordinary perception.

Spiritualism and Faith

The consolation

of poetry could not be entirely sufficient to compensate for the terrible sense

of loss in Issa's life, but he could not accept standard religious precepts

easily either. He was drawn to the fundamental philosophical positions of Buddhist

thought, but his natural skepticism and clear eye for sham prevented him from

entering into any dogma without reservation. Typically, he tried to undermine

the pomposity of religious institutions while combining the simplicity of understated

spiritualism with his usual humor to express reverence for what he found genuinely

sacred: "Chanting at the altar/ of the inner sanctuary . . ./ a cricket

priest." Insisting on a personal relationship with everything, Issa venerated

what he saw as the true manifestation of the great spirits of the universe:

"Ah sacred swallow . . ./ twittering out from your nest in/ Great Buddha's

nostril." The humanity of his position, paradoxically, is much more like

real religious consciousness than the chanting of orthodox believers who mouth

mindless slogans although unable to understand anything of Amida Buddha's message

to humankind: "For each single fly/ that's swatted, 'Namu Amida/ Butsu'

is the cry." Above all, Issa was able to keep his priorities clear. One

is reminded of the famous Zen description of the universe, "No holiness,

vast emptiness," by Issa's determination to keep Buddha from freezing into

an icon: "Polishing the Buddha . . ./ and why not my pipe as well/ for

the holidays?" As Harold Henderson points out, "the boundless love

attributed to Amida Buddha coalesced with his own tenderness toward all weak

things-children and animals and insects." Even in those poems of a religious

nature which do not have a humorous slant there is a feeling of humility that

is piety's best side: "Before the sacred/ mountain shrine of Kamiji . .

./ my head bent itself." In this poem, too, there is an instinctive response

that does not depend on a considered position or careful analysis, thus paralleling

Issa's reacion to the phenomena of the natural world, the true focus of his

worship.

While most of Issa's haiku are like the satori of Zen awareness, a moment of

sudden enlightenment expressed in a "charged image," Issa's "voice"

also has a reflective quality that develops from a rueful realization of the

profound sadness of existence. What makes Issa's voice so appealing in his more

thoughtful poems is his expression of a kind of faith in the value of enduring.

He can begin the new year by saying: "Felicitations!/ Still . . . I guess

this year too/ will prove only so-so." Or he can draw satisfaction from

triumphs of a very small scale: "Congratulations Issa!/ You have survived

to feed/ this year's mosquitos." The loss of five children and his wife's

early death somehow did not lead to paralysis by depression: "If my grumbling

wife/ were still alive I just/ might enjoy tonight's moon." When his life

seemed to be reduced almost to a kind of existential nothingness, he could see

its apparent futility and still find a way to feel some amusement: "One

man and one fly/ buzzing together in one/ big bare empty room." Or he could

calculate the rewards of trying to act charitably, his humor mocking his efforts

but not obscuring the fact that the real reward he obtained was in his singular

way of seeing: "Yes . . . the young sparrows/ if you treat them tenderly-/

thank you with droppings."

Somber Poems

There were moments when the sadness became more than his humor could bear. How close to tragic pessimism is this poem, for example: "The people we know . . ./ but these days even scarecrows/ do not stand upright." And how close to despair is this heartfelt lament: "Mother lost, long gone . . ./ at the deep dark sea I stare-/ at the deep dark sea." Issa is one of those artists whose work must be viewed as a connected body of creation with reciprocal elements. Poems such as these somber ones must be seen as dark seasoning, for the defining credo at the crux of his work is that his effort has been worthwhile. In another attempt at a death song, Issa declared: "Full-moon and flowers/ solacing my forty-nine/ foolish years of song." Since death was regarded as another transitory stage in a larger vision of existence, Issa could dream of a less troubled life in which his true nature emerged: "Gay . . . affectionate . . ./ when I'm reborn I pray to be/ a white-wing butterfly." He, knew, however, that this was wishful thinking. In his poetry, he was already a "white-wing butterfly," and the tension between the man and the poem, between the tenuousness of life and the eternity of art, energized his soul. As he put it himself, summarizing his life and art: "Floating butterfly/ when you dance before my eyes . . ./ Issa, man of mud."

Bibliography

Blyth, R. H. Eastern Culture. Vol. 1 in Haiku. Tokyo: Hokusheido Press, 1981. Discusses Issa in the context of the spiritual origins of haiku in Zen Buddhism and other Eastern spiritual traditions. Sees Issa as the poet of destiny, who saw his own tragic experiences as part of the larger motions of fate. Also interprets him both as a poet within Japanese culture and as a poet of universal appeal.

Blyth, R. H. From the Beginnings Up to Issa. Vol. 1 in A History of Haiku. Tokyo: Hokusheido Press, 1963. Devotes four chapters to Issa, presenting Issa's work in chronological order, ending in the haiku of Issa's old age. Includes interpretations of Issa's work plus examples of his portrayals of plants and the small creatures of the earth and of meaningful personal incidents, such as the deaths of his wife and children. Compares and contrasts him with the great haiku poet Bashô.

Kato, Shulchi. A History of Japanese Literature. Vol. 3. Translated by Don Sanderson. New York: Kodansha International, 1990. Includes a short chapter on Issa as a realistic, down-to-earth poet of everyday life and in the context of the Japanese society of the time.

MacKenzie, Lewis, trans. The Autumn Wind: Selection of the Poems of Issa Kobayashui. London: John Murray, 1957. Lengthy and informative introduction by the translator to a selection of Issa's haiku. MacKenzie assesses Issa's contributions to the haiku form, includes a detailed narrative of Issa's often troubled life, and comments on individual haiku. Includes both English translations of the poems and phonetic Japanese versions.

Yasuda, Kenneth. Japanese Haiku: Its Essential Nature, History, and Possibilities in English, with Selected Examples. Rutland, Vt.: Charles E. Tuttle, 1994. References to Issa and samples of his work in the context of a thorough analysis of the theory and practice of haiku.

Leon Lewis

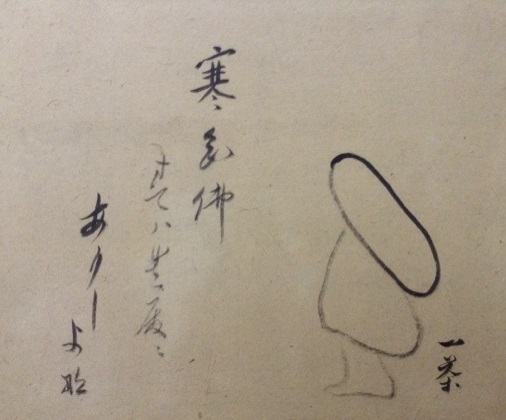

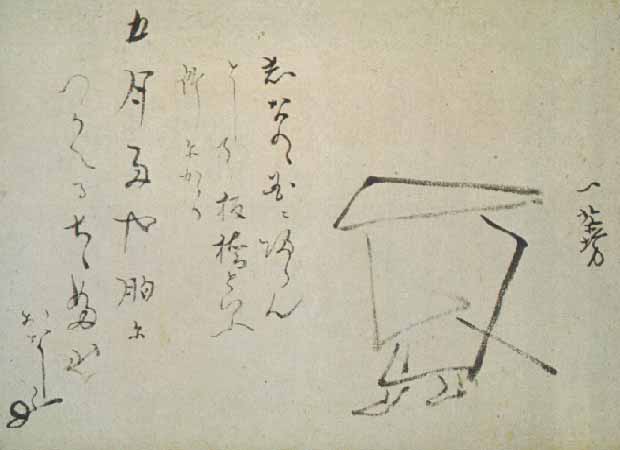

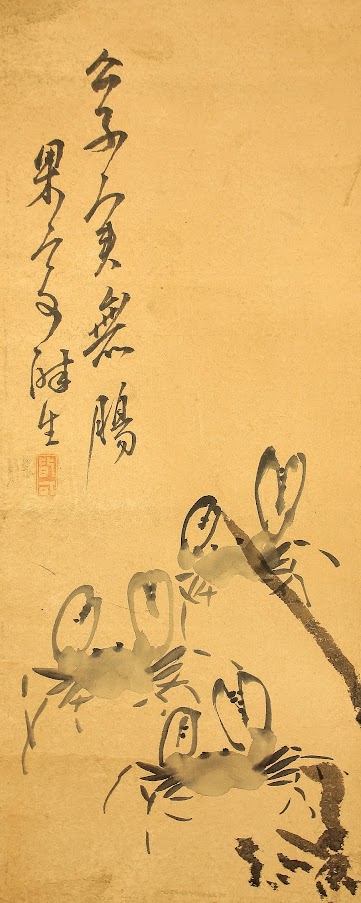

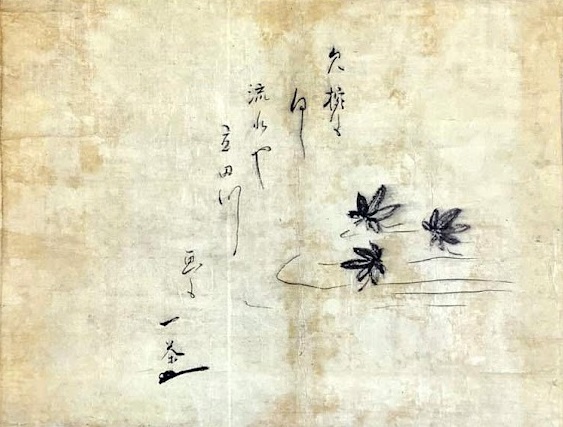

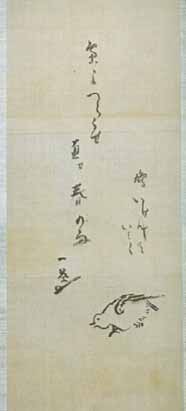

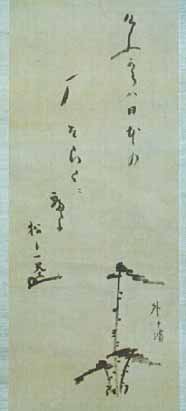

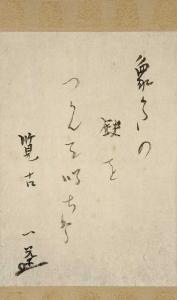

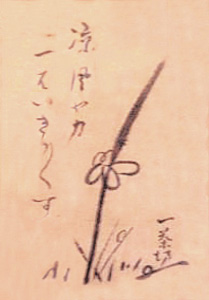

Calligraphic brushworks by Issa

Haiku

written by Issa each in his own calligraphy

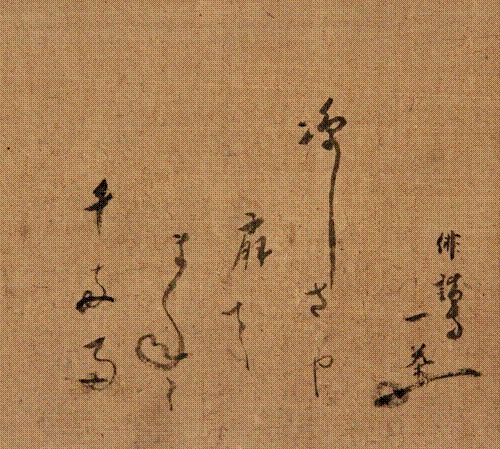

涼しさや 俳句 「涼しさや 扇て まねく 千両雨 」

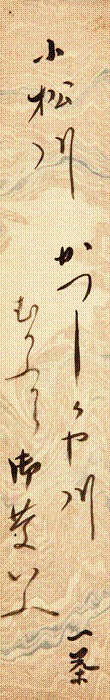

小松川 俳句短 冊

「小松川 かつしかや川

むかうから御慶いふ 」

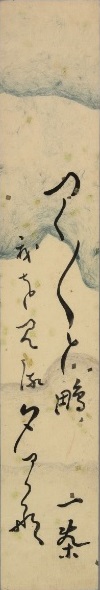

つく ゛/\と鴫我を見る夕べかな 一茶

うくひすや軒去らぬ事小一日 一茶

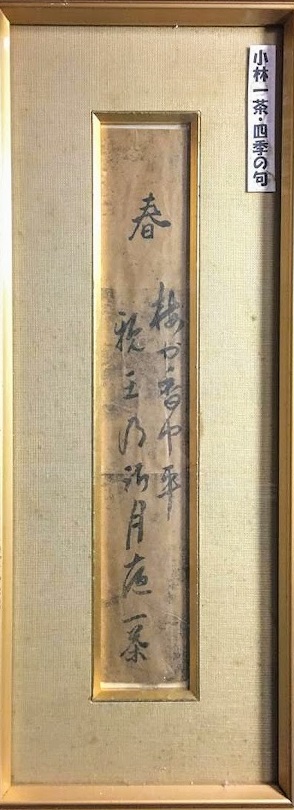

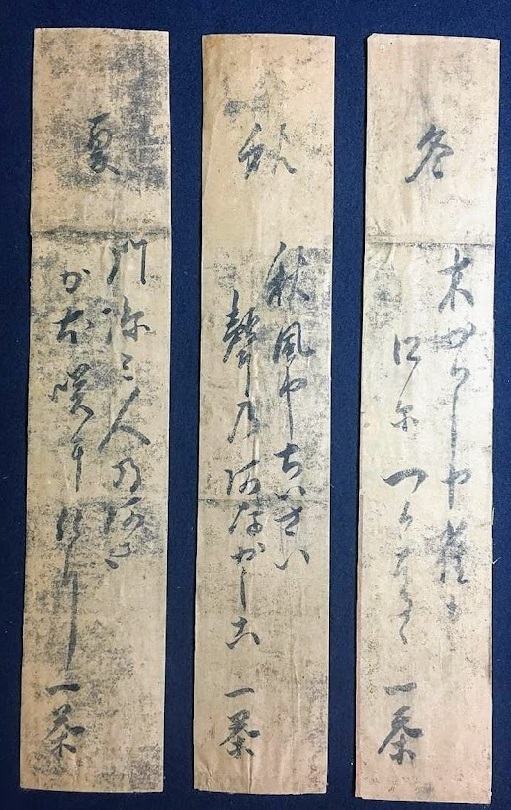

Four Seasons Haiku. Framed size 50 x 20 cm. 4 pieces.

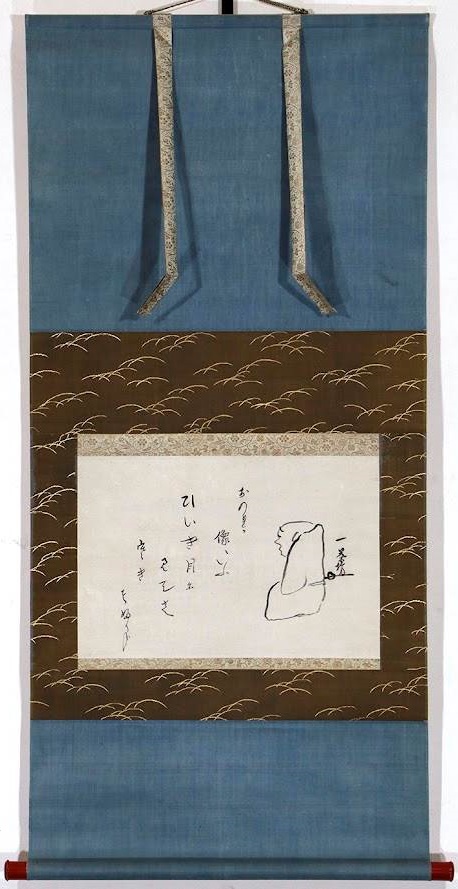

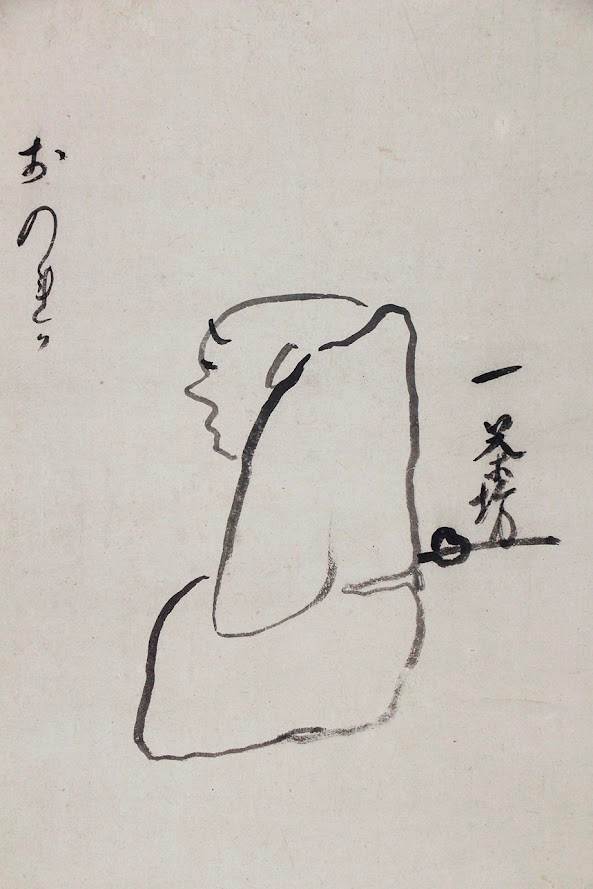

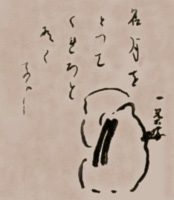

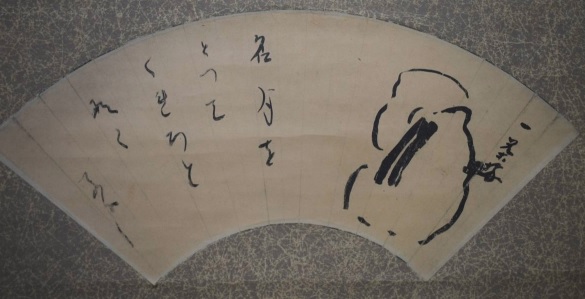

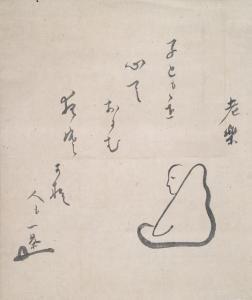

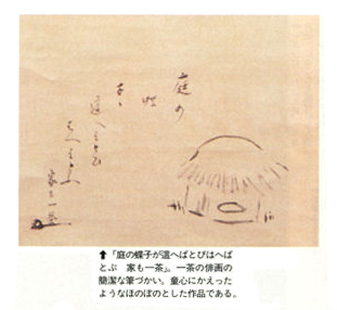

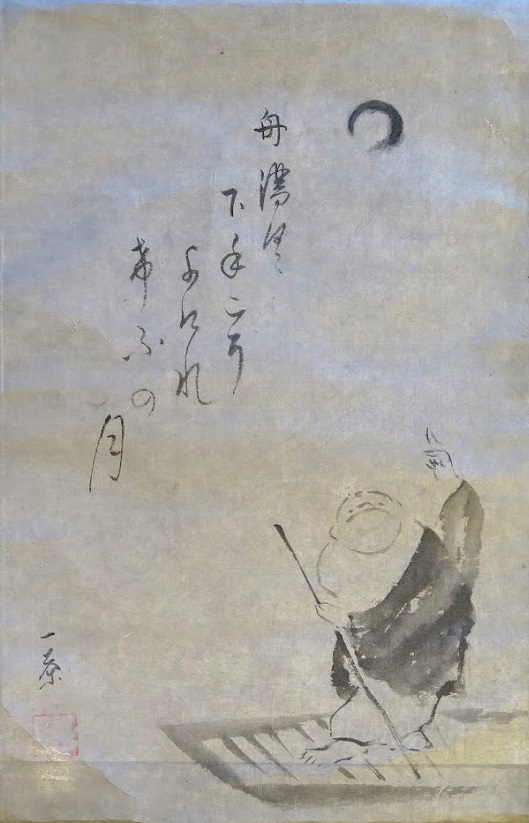

Self-caricature

ひいき目に見てさへ寒いそぶりかな

hiikime

ni mite sae samui soburi kana

even considered

in the most favorable light,

he looks cold

(Tr.

by R. H. Blyth)

名月の御覧の通り屑家也

meigetsu no goran

no tôri kuzuya nari (1808)

lit by the harvest moon

no different...

trashy house

(Tr.

by David G. Lanoue)

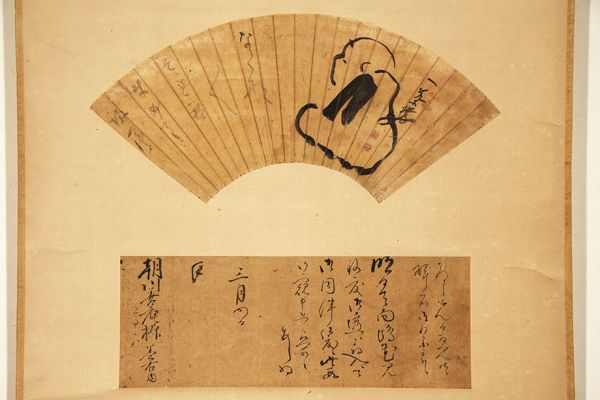

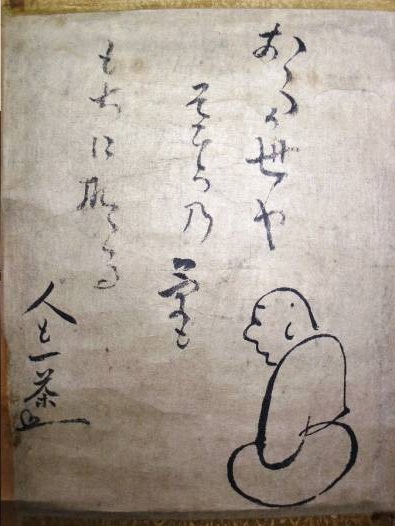

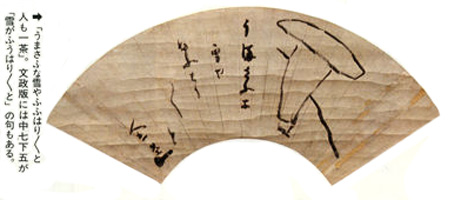

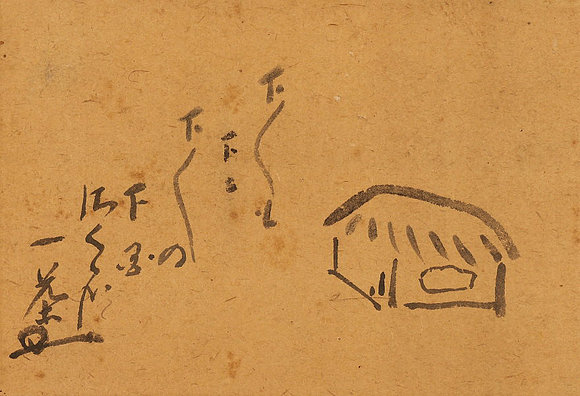

小林一茶 自画像扇面【真作保証】俳人「おらが春」

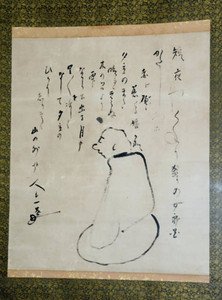

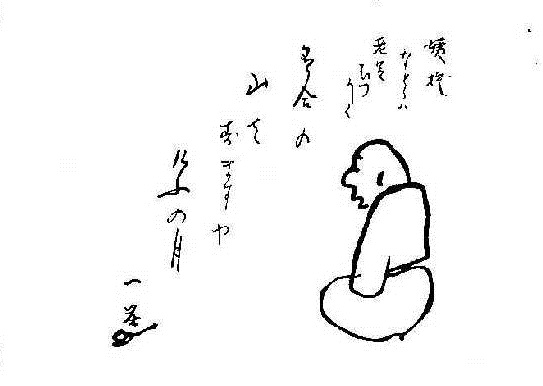

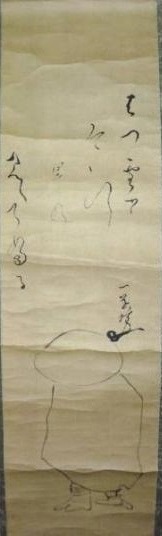

Self-caricature

名月をにぎにぎしたる赤子哉

meigetsu

wo nigi-nigishitaru akago kana (1810)

trying and trying

to grasp the harvest moon--

toddler

(Tr.

by David G. Lanoue)

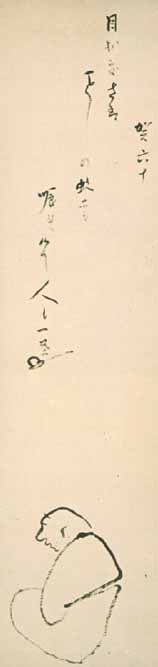

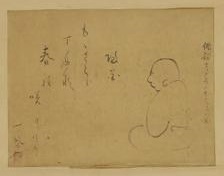

一茶筆 賀六十自画賛 「賀六十 目出度さはことしの蚊にも喰れけり 人も一茶」

「昼の蚊やだまりこくつてうしろから」一茶

姨捨などとは

老足むずかしく

有合の

山ですますや

今日の月

一茶

一茶筆 「五月雨や胸につかえるちゝふ山」

一茶筆 自画賛 「鳩いけんしていはく 梟よつらくせ直せ春の雨」

一茶筆 自画賛 「けふからハ日本の雁そらく二寝よ 松も一茶」

15 × 19 cm

Issa

Yukari-no Sato Museum

5161-1 Oaza Takai, Takayama-mura 026-248-1389

The isolated house, where Kobayashi Issa used to visit, has been restored and

built at this place. Issa's character is introduced by using cartoon pictures

and miniature dolls. The original book of one of his three great works, Chichi-no

Shuen Nikki, and other valuable materials are displayed.

A Handful of Issa

Translated by Scott Watson, 2015

https://www.scribd.com/doc/263118442/A-Handful-of-Issa

Issa by 村松春甫 Muramatsu Shumpo (1772-1858)