ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

内山 (道融) 興正 Uchiyama (Dōyū) Kōshō (1912-1998)

PDF: Modern Civilization and Zen: What kind of religion is Buddhism?

by Rev. Kosho Uchiyama

Translated by Kido Sugioka

The Administrative Office of Soto Sect, 1967, 36 p.

PDF: Approach to Zen: The Reality of Zazen / Modern Civilization and Zen

by Kosho Uchiyama

Japan Publications, Tokyo, 1973. 122 p.

PDF: Opening the hand of thought: approach to Zen

> scanned PDF > digital copy

by Kosho Uchiyama

Translated by Shohaku Okumura and Tom Wright

Arcana, 1993

PDF: Deepest Practice, Deepest Wisdom

by Kosho Uchiyama

The three fascicles presented here from Shōbōgenzō, or Treasury of the True Dharma Eye, include

“Shoaku Makusa” or “Refraining from Evil,” “Maka Hannya Haramitsu” or “Practicing Deepest

Wisdom,” and “Uji” or “Living Time.” Daitsū Tom Wright and Shōhaku Okumura lovingly translate

Dōgen’s penetrating words and Uchiyama’s thoughtful commentary on each piece.

PDF: How to Cook Your Life

From the Zen Kitchen to Enlightenment

Zen Master Dogen and Kosho Uchiyama. Translated by Thomas Wright

PDF: Master Dogen’s Zazen Meditation Handbook: A Translation of Eihei Dogen's Bendowa [弁道話].

with a commentary by Zen Master Kosho Uchiyama Roshi

Tr. by Shohaku Okumura and Taigen Daniel Leighton

Boston: Tuttle Publishing. 1997.

Dōgen Zen As Religion

by Uchiyama Kōshō Rōshi

in: PDF: Heart of Zen: Practice without Gaining-mind pp. 93-134.

Tr. by Shohaku Okumura

This short piece comprises the second half of the book, Shukyō-toshite-no-Dōgen-

Zen (Dogen Zen as Religion, published by Hakujusha, Tokyo, 1977). The first

half of the book is Uchiyama Roshi’s rendition of the Fukan-Zazengi into

modern Japanese and his commentary on it. Uchiyama Roshi dedicated the

book to his master Sawaki Kodo Roshi on the occasion of the thirteenth anniversary

of Sawaki Ro- shi’s death. As Uchiyama Ro- shi wrote in the last part

of this piece, he wished to explain the profundity of Dogen Zenji’s zazen for

students who aspire to practice zazen and enable them to avoid going astray.

Uchiyama Roshi calls Dogen Zenji’s zazen, ‘genuine religion’ in which

all people are saved without regard to capability, talent, education, intelligence,

etc. He also compares it to Rinzai Zen. We should not misunderstand

his intention here. As he says, he makes this comparison for the sake of

clarifying the characteristic of zazen practice as taught by Dogen Zenji, not

out of sectarian bias.

Uchiyama Roshi writes, “The essence of Buddhism is really the self settling

in the self. But the self is not the ‘I’ which desires to improve oneself

and make oneself important. Rather, the self is the basis of the reality of life

which should be studied by letting go of thought and stopping the view of

self and others.” This letting go of thought and stopping the view of self and

others is our zazen.

Shohaku Okumura

PDF: Living and Dying in Zazen: Five Zen Masters of Modern Japan

by Arthur Braverman

Weatherhill, 2003, 176 p.

[A marvelous book combining the life stories and teachings of five masters - Kodo Sawaki, Sodo Yokoyama, Kozan Kato, Motoko Ikebe, and Kosho Uchiyama.]

Seven Points of Practice – Uchiyama

Offered in the last formal talk he gave at Antaiji, on February 23, 1975.

Takuhatsu: Laughter Through the Tears

A life of mendicant begging in Japan

By Uchiyama Kōshō rōshi, former abbot of Antaiji monastery

Translated by Daitsu Tom Wright

Introduction

The following essay on Uchiyama Kosho Roshi's life of mendicancy was written in the early 70's. For roshi, a life of material poverty was taken for granted as a necessity for seeing into and understanding what an authentic religious life should be. A life grounded on zazen and a lifestyle grounded on material minimalism was essential for leading a truly rich spiritual life. The basis for a life of material minimalism is not some sort of asceticism or self-deprivation. There are many examples of ascetics living in Japan. On the contrary, roshi often said that it is the very over abundance of materialism and consumption that so confuses human beings and becomes the cause for so much suffering. He often spole to us of never being afraid or ashamed of material poverty. Dogen Zenji himself urged his followers to always live the minimal material life, but pursue the highest culture (a life of zazen ). Placing this essay within the social context in which it was written, the year was 1968. Roshi was 56 years old. Socially speaking, Japanese heavy industry was beginning its phenomenal economic climb, not in the least thanks to the tanks and other heavy equipment supplied to the Unites States military in its war in Vietnam ( 1 ) Roshi confided to me one day that one reason he wrote Laughter through the Tears ( 2 ) was, in a sense, to thank all the people in Kyoto who supported him during those difficult years of his life of practice. Before reading further, perhaps a brief explanation of the practice of takuhatsu is in order. Takuhatsu is the practice of walking through the streets of the city collecting donations which, in modern day Japan, are mostly monetary. The tradition itself has been handed down through the ages from Shakyamuni Buddha in India, through China and Korea, though in those countries, the donation is usually food. Literally, the Chinese characters mean to “trust in the bowl.” That is, trust that whatever is needed to sustain one's daily life will be provided to the monk or nun. So the attitude of a person on takuhatsu is entirely different from a beggar who simply puts his or her hand out wanting to be fed.

The attitude of one on takuhatsu must be one of equanimity, whether no donation is received or a large one is received. In fact, the attitude of the mendicant on takuhatsu is one of giving an opportunity to people to materially support a life of one dedicated to zazen and the teaching of the Buddhadharma. Finally, I will feel that this translation has been successful if it is able to convey to readers even a little of the humor and pathos, sometimes subtle, sometimes not so subtle, imbedded in roshi's discussion of takuhatsu. The stories are humorous enough as they are, but then after the humor is appreciated, the reader may have to return once more to think about the purpose in roshi's conveying his message as he did. Perhaps the final chapter on why do takuhatsu is the most critical in understanding takuhatsu not simply as a way to get food, but as an attitude towards life.

Notes:

1 ) During the war Uchiyama roshi was sent to a very remote area in Shimane Prefecture by his teacher, Sawaki roshi. He spent the time making charcoal. Later, Sawaki roshi sent him to a place in Shizuoka where he made salt from seawater. Both of these tasks were meant to protect him from having to go into the military. Sawaki roshi was fully aware that his disciple, Kosho, was not physically strong and certainly not suited for military life. Facts like this about how Sawaki roshi protected his disciples from the ravages of war are little known and have never been publicized. Actually, Roshi was drafted into the military exactly one week before Japan surrendered in 1944.

2 ) In Japanese, Nakiwarai no Takuhatsu.

Daitsu Tom Wright, July, 2005

[Wright was ordained by Uchiyama Roshi in 1974 and is a professor of English at Ryukoku University in Kyoto, Japan.]

Unromantic life

Here we are living in an age with jet planes streaking through the sky while on the ground, gravel trucks race down paved roads—But what is this coming down the street! A figure in black robes and long open sleeves, with a black bag around his neck, a huge straw hat on his head and wearing white spats and straw sandals. He walks from door to door, holding a bowl in front of him, the times filled with laughter and tears. This is “takuhatsu,” mendicant begging by Buddhist priests. The bowl they carry is their eating bowl, it is the same practice of Buddhist monks throughout Asia since the time of Shakyamuni Buddha. People put either money or rice into the bowl and as it fills up, the priest empties the contents into the black cloth bag hanging around his neck. Today, at least in the cities, most donations are monetary, not food.

The famous Japanese Zen monk Ryokan ( 1 ) lived by takuhatsu and wrote about it in his poems. Picture a warm spring day, the flowers in full bloom, the warblers singing away and beautiful butterflies flitting here and there. That surely must have been the setting for Ryokan's walks through country villages from one farm house to the next. Children would run in delight to greet their familiar playmate. Ryokan, always happy to see the children, puts down his bowl and joins in the children's games. Poor Ryokan, the day passed quickly while he was absorbed in the games with the children, completely unaware that all his rice has been eaten by the sparrows in the grass.

The deep resonating sound of a nearby temple bell announces that it is the end of the day. The light of the early evening moon shines brightly and the children have all headed home. Suddenly, Ryokan feels a tinge of loneliness and heads back to his own grass hut. He turns and runs back to the village where he vaguely remembers having left his bowl hours before. Just picturing Ryokan all flustered returning to the village to fetch the bowl can't help but bring a smile to my face. Of course, I would have liked my takuhatsu to have been that sort of idyllic, simple kind, too. Unfortunately, the reality of my life of takuhatsu was anything but that. In fact, it was the extreme opposite of the idyllic, simple takuhatsu lifestyle. If in going out on takuhatsu, you can do so with the attitude of, well, if people put something in my bowl, that's fine and, if they don't that's okay, too, then you can say that your takuhatsu is ideal with no complications. However, I was unable to do that. I was dead serious about it, and I couldn't hide my feelings. As long as I was going out, I felt I just had to bring home a certain amount of money–I had my quota to fill. Not only that, I felt I had to do it in the most efficient way, because I needed to get back to the temple as quickly as possible, so my story becomes even more pathetic. It wasn't because I wanted to take a rest that I desired to get right back to the temple. Rather, besides takuhatsu, I had a lot of other work to do that made my going out all the more important. Knowing how much work waiting for me at the temple, there was no way I could ever feel what I was doing was in any way refined elegant or “spiritually uplifting.” But, everyone in the world has feelings of being pursued, and of living from hand to mouth. I am not talking about my presentday life. The period I'm talking about began in the summer of 1949, when I first arrived in Kyoto, and lasted until the spring of 1962. That is, from the age of 37 until I reached 50. So, perhaps because there is a certain amount of distance between those days and my life now, I am able to talk about the sweet and bitter of takuhatsu.

Notes:

1 ) Yamamoto Ryokan. (1758 ~ 1831) A Japanese monk who lived in the Edo period and was famous for his poetry and calligraphy.

The lifestyle behind takuhatsu

Once you start down the path of poverty, there seems to be no limit to how far down you can go. I had been prepared for it by the life I led during the war prior to settling at Antaiji, which was even worse. In 1949, when I first began going out on takuhatsu in Kyoto, the emotion and poverty of the war years had not yet subsided. In that kind of economically difficult environment, the number of fellow practitioners diminished greatly. Finally, there were only two of us left at Antaiji, the leaf flute artist, Yokoyama Sodo and me ( 1 ). On top of that, Antaiji had deteriorated so badly during the war that so Sodo had to go out on takuhatsu for funds to refurbish the broken-down temple, while I went around on takuhatsu to supply us with food and also to cover sesshin expenses. I was not only going out on takuhatsu, I also had to take care of the vegetable garden and fertilize it, cut and chop the wood for cooking and heating the bath, plus make our pickle supply, weed and keep up the grounds, clean the temple, and so forth. On top of that, I prepared three meals a day and if I didn't go out on takuhatsu, I had my laundry to do. So, obviously, I couldn't blithely go out on takuhatsu like Ryokan and enjoy playing with the children along the way. Far from it, I had to keep my mind on how to juggle doing takuhatsu and caring for the temple. I had to figure out how to cut corners everywhere to get a little extra time for zazen and study. Being careless with even one piece of firewood meant that I would have to take that much more time to chop and cut up wood. Or, if I left a light on needlessly, that meant I had to go out on takuhatsu to pay for it. Cutting back on needless expenditures was absolutely critical for the kind of frugal life we were leading. Our life was always on the edge. When Sawaki Roshi would come back to Antaiji to lead sesshin, I wanted to have a special treat of lotus root on his tray for him, I would go to the market to get some and not have the few yen the greengrocer asked for. Here was this forty-year-old adult having to say, “Oh, my God, if it is going to cost me that much, I will take something else.” We were really in a pitiable state. If I had had a wife and family to take care of, I would have broken down completely. Fortunately, I was single then.v Needless to say, in those days I was never able to purchase any new clothing such as robes. Actually, from the time the war began in 1941, I was never able to buy any new clothing, and everything I had was tattered. Even the covering on my futon was all torn up. Going to bed was like covering myself with the cotton padding that is inside futons. If I got sick for a couple days and had to rest, my whole room seemed to be awash in dust balls of cotton batting. Old newspapers served as toilet paper. Our washcloths looked like some sort of netting, since I used them far beyond the point where they resembled washcloths. Even though they only cost ten or fifteen yen at the time, I couldn't afford new ones. I did have one bad habit that I just couldn't give up—smoking. I would collect half-smoked cigarettes left behind by guests and smoke the tobacco in long reed-like pipes—pretty despicable, I admit. In those days, Antaiji looked gruesome. The tatami in my room were completely torn up with straw popping up out of them here and there. And the floor joists supporting the tatami were as soft as cushions. Twice I fell right through the floor. I just took a couple of orange crates that were lying around and used them to prop up the joists and finally, laid the totally torn apart tatami down. The normally white-papered shoji looked like a patchwork quilt with slips of paper pasted over the holes. But what could I do, I had neither the money nor the time to make any proper repairs. Antaiji was truly a dreary and desolate place in those days. This made it imperative that I put all my energy into takuhatsu. Although it would seem to be nothing more than walking around shouting, “Ho~~~!” when you go out on takuhatsu, you are risking your life, One little mistake in judgment and you're liable to find yourself sprawled out on the street, with one yen coins scattered all around, having been hit by a car. Moreover, the emotional burden is incredible. When an able-bodied male is just walking around begging for money, people look at him with contempt. Enduring that look is far more difficult than enduring even some half-baked job. And in the end, the amount received is barely a pittance. Besides that, while the monk on takuhatsu is the very last person to receive any material benefits when times are good, he is the very first in line to feel any economic downturn. By the mid-fifties, people mostly thought that the war was completely behind them, but for people like us, the war was barely over. Occasionally on late autumn days Sodo and I would trudge back to the temple as the sun was going down and see a praying mantis clinging to the shoji along the west side of the building. The mantises, themselves yellowish brown in color, looked like withered leaves. They would be warming themselves in the last rays of the day. The mantis finishes laying its eggs in late September and from then until about the middle of November, it seems to search out a warm spot, sitting there through chill winds and showers as though just waiting for the end to come. I always got a lump in my throat when I came across a praying mantis in the late fall. With all worldly connections cut off, just living the whole of its life by itself, breathing in and out and clinging there, not moving, waiting for death—somehow the image of that mantis at a dilapidated temple at the end of autumn was equally a picture of us. Sodo, too, must have been deeply moved by this, because he composed the following verse.

Autumn mantis clinging

to the white paper I glued to the shoji

where did it come from and where did it go?

These sad and lonely thoughts came and went in our hearts, but it isn't really right to use the plural “in our hearts” here. Each of us had to bear his own life and in his own heart. Sodo was living out his life, and I was living out mine. We were side by side in this life at Antaiji, and at the same time, each of us was completely alone. Such thoughts came and went in each of us. They were part of the scenery of Sodo's life of shikantaza, as they were for me. Precisely because takuhatsu was a part of our overall life centered around sitting zazen, it was a life of entrusting our lives to the bowl completely. If there had been no zazen and only begging, my life would have been nothing more than a pitiable life of poverty ( 2 ).

Notes:

1 ) Yokoyama Sodo Roshi, (横山祖道 Yokoyama Sodō (1907-1980). Yokoyama Roshi was always interested in poetry and music. After he left Antaiji, he moved to Komoro in Nagano Prefecture and home of Shimazaki Toson, a famous Japanese writer and poet. A park was named after Toson and Yokoyama Roshi lived there during the day and did zazen. In his later years, Yokoyama Roshi's' takuhatsu consisted of writing poetry and musical compositions, for which visitors strolling through the park would donate money. He became well known for his unconventional life and his flute-playing and was occasionally to be seen on national television.

2 ) During this period of his life, Roshi was single, although he had been married twice before becoming a monk. His first wife died of tuberculosis when roshi and his wife were in their mid-twenties and his second wife died in childbirth (along with the child) when roshi was in his late twenties.

Kyoto's other mendicants

Many of the major Rinzai training monasteries in Japan like Daitokuji, Myoshinji, and Nanzenji are located in Kyoto. The monks go out on takuhatsu through the streets of the city, all of them carrying bags around their necks with the name of the monastery clearly written on the front of it. Occasionally, I have stopped in front of a shop and some woman would come out and ask politely, “Oh, are you from Myoshinji?” “No,” I would reply, “I'm from Antaiji.” Suddenly the bright, friendly smile would disappear from her face and with a very skeptical eye she would look me up and down and deftly place a one-yen coin in my bowl instead of the ten-yen coin she had been preparing to give me. At times like that, I have felt so wretched. Going out on takuhatsu from Antaiji was not selling some famous brand name or reputation. I was often treated more like an ordinary beggar than like a religious mendicant. One thing people out on takuhatsu cannot abide are all the other people plying the trade. Among the beneficiaries of begging are, first of all, those monks and nuns from the “name brand” monasteries. Then there are monks wearing picturesque pointy hats and carrying a staff with metal rings on top that jingle as they walk around, or the Nichiren monks pounding their drums, and then there are the goeika Buddhist hymn singers walking around. I mustn't leave out the mendicants of the Zen Fuke sect, playing the shakuhachi as they go around wearing the special straw hat that covers their head and face completely, plus the yamabushi, the itinerant mountain hermits. And, last but not least, there is the ordinary garden variety beggar. I once heard from one of the shop owners that on average five groups a day passed by looking for a handout. It follows that the first who come will get the best donations. That means the first fellow might get twenty yen, the second, five yen, and by the last one, down to one yen, if he or she were lucky, or perhaps nothing more than a “Get lost!” Just in terms of human emotions, this is understandable behavior. One day I went to Yamashina for takuhatsu. I used what little money I had to get there on the electric train. When I got off the train I took the side streets first, saving the best street to do takuhatsu for last. But just as I turned the corner to start down Plum Street, lo and behold, a komuso mendicant playing the shakuhachi came toward me from the opposite direction.vii He had obviously just finished making a stupendous haul! I felt just awful. To rub salt in the wound, the monk stopped in front of me and, with the utmost composure, said, “Pardon me for going first,” and continued on his way. Inside, I wanted to shout, “You rat, I've been saving this street for last!” But I took one look at his smirkingly proud face and the whole situation suddenly seemed so absurdly funny to me that I gave him a forced smile and bowed back. I suppose you could call that a sort of unwritten etiquette between mendicants. Another time I met one beggar three days in a row. The first day I met him was in southern Kyoyo near Oishi Bridge, on the second day, we crossed paths up north near Kumano Shrine and the third day, I ran into him near Kyoto Station. Running into him on that third day, I felt as though I had run into a colleague working in the same line of business. I almost called out to him, “Hey, how are you making out?” At the time, I guess a feeling of embarrassment came over me and I never did call out to him. Looking back on it now, I wish I had invited him to some nearby cemetery to take a rest and share a sandwich or something. At the time I looked at him thinking, “Oh, there's a guy in the begging business.” And I am sure he must have looked at me with the same eye. I never knew whether he went up in the world or down, although I occasionally glimpsed him begging from door to door, ringing a small bell and reciting and singing a hymn.

Takuhatsu neurosis

I had some experience of takuhatsu before I moved to Antaiji, when I lived in temples out in the countryside. There were several of us going out together just once or twice a month, so the atmosphere was more like going on an outing, and besides, it wasn't as if our lives depended on it. In Kyoto, my situation was totally different. Antaiji had absolutely no other income, and it was a burden to set out alone knowing that I had to bring back a certain amount, and on top of that, knowing that the amount was really not much. I had to go out every day it didn't rain, so it didn't take long before everyone in town seemed to know my face. Once my face became familiar, shopkeepers would give me an “Oh, God, here he comes again” look. And I would show a “Hi, well, here I am again” look. After a while, I started becoming not just depressed, but totally intimidated. Just before going out for the day, I would imagine the street I was about to do down for the day and very clearly in my mind, I could picture the tobacconist on the corner and the barber shop next door, then the sweet cake shop, and the hardware store and beyond that the fish monger's. I would imagine everyone giving me the “Oh no, not that guy again” look, and I would start feeling truly dark and gloomy. Once I reached the street, without stopping to think about it I would start walking down the street muttering under my breath, “Namu Kanzeon Bosatsu, Namu Kanzeon Bosatsu—I take refuge in you, Bodhisattva Avelokitesvara!” At last I arrive at the intended street and, sure enough, the street is laid out just as I had pictured it in my mind and, sure enough, I'm beginning to feel depressed. I find myself standing in front of that first house, intoning the takuhatsu greeting, “Ho ~~~~~” in the most timid of voices. And, sure enough, the woman comes out of her house and gives me that disgusted look I knew she would, and blurts out, “Move along, there, you're blocking the way.” I just get more depressed and shuffle along to the next door. Just as I expected, the man there shouts at me without any mercy, “Hit the road, buster!” Now my voice is getting even tinier as I step up to the next shop. The lady comes out and with a disgusted air tosses a measly one yen bill into my bowl as though she didn't really want to but felt obligated. Now I begin to almost cower in front of every house and after taking a quick glance at the owner, I move on to the following place without looking back or even intoning the usual takuhatsu greeting. So here I am faced with a dilemma of having to go out every day because I have to bring in so much money just to survive, while at the same time walking through the streets of the city with virtually nothing coming in. So while going out every day walking my feet off from morning ‘till night, I really began to develop a neurosis. It was three years after I came to Kyoto and began going out on takuhatsu on a daily basis that I reached this impasse. It took three years to become a thoroughly familiar face. And then, though I received grudging recognition as a monk, people still seemed to look at me as that guy in the begging business. At any rate, I had convinced myself that people were looking at me in that way. And, there I was just going through the motions with almost nothing being dropped into my bowl. This kind of takuhatsu neurosis continued for about a year. I'm not very good at insisting on things going my way, but I tend to be a fairly persevering person; if there is a wall and I keep pushing at it, I tend to believe that eventually it will fall. So, I just kept at it and about a year after I had developed this neurosis something very important dawned on me. One day while standing in front of a certain house and not giving a thought as to whether anyone would put something in my bowl, I realized my attitude had changed. It was just putting all my energy into standing there without any reservation and looking straight ahead at the people who came out until they said, “No, nothing for you today.” When I realized that, I suddenly felt a sense of relief. Even though many people might be thinking, “Oh, god, here he comes again,” when they saw me, I no longer had that dark, dreary feeling. It even seemed to me that people were beginning to express a certain friendliness. From that time on, the people of Kyoto began to cheerfully put money in my bowl. Going out on takuhatsu is a little bit like a salesman making his rounds. The only thing is, there are no goods to give in exchange. And, because of that, there is always a sharp prick of conscience about it. As long as one is unable to feel a sense of joy despite the degrading spirit of being reduced to receiving something for nothing, then I suppose it is only natural to feel the barb of shame. No matter how long one goes out on takuhatsu, I don't think that feeling ever completely disappears. There is a traditional saying, “If you beg for three days you'll get a hankering for it, and you won't be able to quit.” It seems to me that it is better to continue doing takuhatsu while feeling a pang of conscience. Becoming neurotic over it, however, is going too far.

Living like a pigeon

Although this may seem like an overblown way of putting it, to get over my neurosis regarding takuhatsu, it was necessary for me to become personally aware of my religious mission to society as a mendicant priest. Even during that period when I was personally depressed and feeling terribly intimidated by going out and there was so little coming into my bowl, the people of Kyoto did donate something to support me, despite the fact that in those days, most people would look around for the cheapest place to buy an eggplant, even to save just one sen. During my entire life of practice, I was supported entirely by the people of Kyoto, although it used to puzzle me just what motivated the local folk to put money in the bowl of a monk out on takuhatsu in the first place. One day I was taking a lunch break in the confines of Toji Temple. As we always had rice gruel for breakfast at Antaiji, it was not practical to prepare a lunch of leftover breakfast, so I usually bought a couple of rolls. I often ate on the grounds of a temple or shrine, or in a temple cemetery. Nowadays, the grounds at Toji are all fenced off and they charge money just to get in, but in those days there were no fences or places that collected entrance fees—it was an ideal place to rest and eat a roll or two. Pigeons approached and I would break off a little of the bread I was eating and share it with them. Particularly during the period when I was so depressed about going out in the first place, watching them eat the few crumbs I tossed, somehow cheered me up. At some point, if I knew I would be stopping off at Toji, I got into the habit of buying an extra roll to share with the pigeons. As I was feeding the pigeons one day, I realized that I, too, was one of the pigeons of Kyoto. When the pigeons came around, people would want to feed them if they had any bread leftover simply out of human sentiment. In the same way, if some monk happens to stop in front of your house, you might think that another one of those pigeons has come around, and you open the door and toss one or two yen into his bowl, just as you would toss bread to the birds. I realized that, in a sense, I had to behave and appear attractive just like one of those Toji pigeons. Now in Kyoto, there were plenty of pigeons at other temples, too, but they were pushy. If you looked like you were going to give them some bread, they would come right up onto your hand, take it, and then go after the bread you had intended for yourself. When they started doing that, I would feel reluctant to feed them anymore. The pigeons at Toji would approach to within a couple of feet. And when I would drop the crumbs about a foot away from me, they would do a little hop, peck at the bread and then quickly jump back a couple feet. This reticence on the part of the pigeons was really quite charming. I decided that from then on I would be like a Toji pigeon. I began to play my role gladly, adding to the ambience of this city as a monk doing takuhatsu. My style of doing takuhatsu became more reserved and less pushy, and I stopped thinking in terms of how much money I needed to get in my bowl each day. I went from one house to the next as quickly and lightly as I could. And before I knew it, people got used to my new style. They began putting coins in my bowl almost before I had a chance to show my face. Sometimes while passing by the front of an open shop I would notice that the shopkeeper was on the phone, so I would just keep walking by. Surprisingly, people would finish their call and chase me down the street to put something in my bowl. How could I be anything but grateful when people would do that kind of thing. One day I was sitting on the electric train on my way back to Antaiji from a day out. It was cherry blossom time, the train was crowded and I was standing there holding onto one of the leather straps with one hand and a paperback in the other. A man sitting just down the aisle and looking rather drunk spotted me and shouted, “Oh, monk, come on over here, there is a seat open.” As he was pretty far into his cups, I would have preferred to ignore him, but since there was a seat open and I was quite tired from the day's outing, I worked my way over and sat down next to him. He tried to engage me in conversation, but I made perfunctory replies and went back to reading my book. He leaned over to see what I was reading, but unfortunately for him it looked rather difficult, so for a while he just sat next to me without saying a word. Then, all of a sudden, in a most serious tone, he said, “You keep on practicing good and hard, now. Look around. Even though everyone is all caught up in looking at the cherry blossoms, here are guys like you going out on takuhatsu. I'm just a tinsmith, and sometimes when I'm working there in the shop, we can hear the ‘Ho——' of some monk coming down the street. My little girl runs over to me and says, ‘Papa, give me some money!' She quickly takes the two yen or three yen I give her and runs out to put it in the monk's bowl. And inevitably, the monk very politely bows very low to thank her and then goes on his way. You know, for two or three yen, you don't have to be so polite and do a full bow like that. Anyway, you practice real hard, now. All the great ones like Ikkyu lived off takuhatsu. If we keep on giving to monks, even if we can't afford very much, some day another Ikkyu will come along—I'm absolutely sure of it.” I closed the book I was reading and looked straight at this drunk sitting next to me, but all the drunkenness had disappeared from his eyes, and he looked back at me most soberly. In many districts of Kyoto there are still people who think like that guy.

Is there such a thing as luck?

By the time I was finally able to throw off my takuhatsu neurosis, my philosophy regarding luck had pretty much taken shape. Generally speaking, I‘m not interested in talking about fortune or fate. As a human being trying to live out the spirit of genuine religious teachings, you have to have the fundamental attitude of facing whatever comes up regardless of good luck or misfortune. Every time you try to succeed at something that is a little beyond your natural capacity, you generally wind up crying over the spilled milk of your failure and, to that extent, there can never be any total peace of mind. When you settle on an immovable peace of mind as your true religious practice, this has no connection whatever to luck, good or bad. The zazen practitioner has to sit bearing in mind those words of encouragement, “Every day is a good day,” and “Whatever happens this is an auspicious occasion” ( 1 ) . Although whichever way things evolve is fine, we still have to do our best to make good choices. If you are driving down the street and have the choice of either sticking to your own lane because that is the correct one or moving over into the opposite lane to avoid colliding with an oncoming car that is careening down the road at you, then moving out of the way of the oncoming car is the way your life should fall. When I went out on takuhatsu, I could do so with a simplistic attitude of just going for a walk whether anyone put something into my bowl or not. But if my life depends on takuhatsu, and I need to do it efficiently in order to have time to do the other work in the temple plus have time for zazen and study, all of which constitute the vow by which I live my life, it is only natural to choose a route where I know the contribution is likely to be generous. The true meaning of “whatever way I fall” doesn't deny luck or fortune. It sees luck happening within whatever way I fall. That is, even if I fall into good luck or circumstances, that is my great joy. And, if I meet some bad luck, then that is my joy and fortune. Being happy and laughing, every day is a good day. And, likewise, being sad and hopeless is also a good day. Thinking that once we have attained deep faith or have had some great enlightenment experience our whole life will be one joyous delight after another and all sadness will be swept away, so that all we can see is paradise. This is nothing but a fairy tale. Living a life of true reality, while experiencing an ongoing restlessness of, now a moment of alternate moments of joy and sadness, actually, there has to be a settling into one's life in a much deeper place where you face whatever comes up. Likewise, true religious teaching is not a denial of our day-to-day predicaments, it is not cleverly glossing over reality, or feigned happiness. On the contrary, true religious teaching has to be able to show us how we can swim through one wave at a time, that is, those waves of our life of now laughing, now crying, the waves of prosperity or adversity. Studying and practicing the buddhadharma is neither a kind of academic exercise to be carried out only after your livelihood has been secured, nor some sort of zazen performed when circumstances are favorable. I was forced to search out what true religion is when I was not unlike a stray dog always badgered by anxieties over daily life, having to pick up whatever scraps I could. As long as we are alive, there will always be fortunate things and unfortunate things happening in our lives. Inevitably we go through times of utter collapse as well. Frequently, during that period prior to throwing off my takuhatsu neurosis, there were days when one person after another would tell me to go away. Sometimes I would just get so demoralized that I would quit and spend the rest of the day at the zoo. Or, if I didn't have any money, I would go to the library wearing my sedge hat and straw sandals. But, eventually, as I grew used to going out, I began to discover that even on days when I would start off badly, instead of becoming depressed, I began to think instead that I was just unlucky that morning. Little by little, I would get back my sprit and walk through the streets searching for that gold vein and, inevitably, my luck would change. When you start off like a house on fire, then you have to pay particularly attention, because while you are all relaxed thinking about what a great morning it has been, bang, your luck doesn't last forever. Your happy-go-lucky attitude is clear to those around you and you end up having to go home with even less than average. Whenever I started off badly, I just figured later my luck would change for the better. And when I started out lucky, I knew I would have to be on my toes. No matter how much experience you have had, there are times when your intuition about where to go that day completely misses the mark. When one is restricted to bringing in the most results in the least amount of time, completely missing the mark can be critical. You could say that good fortune or luck comes into play precisely when you are looking for a certain result in a limited time. But if you are looking at things from the viewpoint of eternity, then there is no such thing as luck. While settled in the attitude that whichever way our life falls we feel grateful, we can feel the varying textures of fortune and misfortune in terms of joy and bitterness during the day's walk. If we look at humankind from a long view of billions of years, this animal called Homo sapiens is nothing more than a single existence that suddenly appeared in this universe and will leave it without a trace. A single day in the life of this very small human species is just one tiny joy, one minute of bitterness. Without an attitude that whatever happens is okay, we are going to wind up neurotic. Still, even though whatever may happen is okay, if you do not apply any businesslike principle to your activities, even to one like takuhatsu, you will end up a fool. Going the Middle Way between the neurotic and the fool is precisely what doing takuhatsu is about.

Notes:

1 ) Uchiyama Roshi has taken the first character of the Chinese word for fortune which is kikkyo 吉凶 and combined it with another character to form the Buddhist term for auspicious or joyous, which is kichijo 吉祥 .

Takuhatsu as a business

Needless to say, before falling back on luck, it is better to apply creative savvy. I think we can call takuhatsu a kind of enterprise, albeit not a particularly large-scale one. If the aims of the management are misguided, the company will go down the drain. A healthy business requires always looking at the big picture. Applying this to takuhatsu, we naturally have to have a “business map,” but a takuhatsu map is not a kind of tourist information map or road map. You have to mesh your own needs with the prosperity of the neighborhood. You have to decide how often your going for donations will be acceptable to the people living there. Practically speaking, if all the shops in a particular area seem to have a steady stream of customers, you can conclude that the district is fairly prosperous, but you still need to avoid being burdensome for the community. Therefore, you draw a line at once a month. On the other hand, sometimes there's an area that always contributes well, but is obviously an economically challenged area. You have to put yourself in their shoes and see how difficult it must be for them to give so much; even though they are good contributors, maybe two or at most three times a year would be best. When I would go out, I would take note of these things in my mind and add them to my takuhatsu map. If you don't consider them, and go back three or four times in quick succession just because they put a lot of money into your bowl the first time, you are going to be in for a shock. They will get to know your face and will not only stop putting anything in your bowl, they will stop looking at you at all and your bowl will soon dry up. The reason I think I was able to continue takuhatsu for over ten years without my bowl ever being bone dry in a city as small as Kyoto, and receiving the patronage of the local people while raising my “sales” results consistently, was my “business policies” in regard to takuhatsu as an enterprise. The heavy atmosphere just before storms are strangely good times for takuhatsu. The sky above the northern mountains becomes pitch black, the thunder begins to roll and the clouds move ominously closer. At those times, I am resigned to getting a good soaking, but as I keep on takuhatsu, the storeowners begin running outside to get everything under a roof or awning. And when I stop in front of a shop, the owner wastes no time in putting something in my bowl. Right away, I move on, and right away, the next fellow comes out to put money in the bowl. These few minutes of confusion and hurrying around just before the storm hits are great for raising efficiency. Dusk at the vernal equinox, works the same way. At that shadowy time of the day, just about the time it feels like there could be some sort of demon lurking around the nearest corner, the atmosphere in the streets turns somewhat frantic. Kyoto seems to be a place where you would almost expect some eerie spectacle to appear from out of the shadows. People in Kyoto have long dhad this fear of malevolent spirits. No doubt the thunder and the early evening of the equinox generate the expectation of spirits and goblins swaggering about. It is in just that atmosphere that a monk out on takuhatsu matches the need of the people and surely this boosts sales. Festivals are another special occasion. Right up to the start of the festival is great for doing takuhatsu, but once the floats start rolling down the street, forget it. It is the same during a fire. At times like this, what else is there to do but enjoy the parade?

Nothing carries over

One of the good things about takuhatsu that makes it different from other business enterprises is that there is no carry over from one day to the next. There are no credit sales and no outstanding debt. There is no capital outlay and no bouncing of checks that might cause someone to track you down. Far from it, the worst thing that could happen is that some unsympathetic person whose house you are standing in front of comes out and yells at you to go away. For the moment, you feel rather down at the mouth, but then you move on down the street and some very attractive young woman comes out holding a cute little baby and gives the smiling child a coin to drop into your bowl. Bingo, you feel all happy and warm again. Or, perhaps some old grandmother appears and bows ever so politely. As she puts some money in the bowl, stands there reverently while you while you recite the verse of thankfulness, and then bows again in thanks. So now, there you are, bathed in the religious atmosphere of deep mutual respect. The money she put in the bowl seems all the more precious and you can't help but thank her from the bottom of your heart. I guess this is just another inevitable outpouring of human sentiment, in any case none of this carries over to the next day. Actually, there isn't any carry over even to the next instant. Still, it is my ongoing prayer that as we are alive for such a short time, we carry the feeling of caring for each other through each moment of our life. Although I said there are no carryovers from one moment to the next, sometimes there are people who ask for change. One day an elderly lady stuck out a ten-yen note and said, “Look, I will give you three, you give me seven back.” So, there I am chanting the verse of thanks while fishing in my bag one yen at a time for change. The thought of such a scene may bring a smile, but I can tell you personally, the reality of it is not pleasant. Occasionally a guy comes along who looks at me like I'm a moneychanger, and thrusting a hundred-yen note in my face says, “Now, I'm going to give you five yen, so give me the rest back.” Sometimes, takuhatsu can taste pretty bitter.

A few grains of sand

Walking along on a crisp autumn day, the long sleeves of my black robe billowing in the wind, there really couldn't be any greater feeling of elegance than that. In Kyoto, most offerings are monetary, although sometimes other things appear in the bowl. There was one elderly lady who used to call me into her home where she would go back in the kitchen and bring out two fistfuls of rice and empty it into my bag. I could never help thinking, if only her hands were a little bigger. On the other hand, to receive a lot of rice would make the bag around my neck a lot heavier and I would wind up going home with stiff shoulders. Besides rice, I would sometimes get a baked potato from the baked potato man or a sweet cake a street vendor. A nun who lived in a separate house on the grounds of Antaiji used to come home with all kinds of things. One time she even brought back a fish. Monks are never that lucky, although one time I did receive four loaves of bread. It made me very happy, but the thing is, four loaves of bread won't fit into the black bag. On top of that, I had just begun the day's walk, so I couldn't quit and head back to the temple. Thankfully, the sleeves on our black robes are very long, so tucking away a few loaves of bread was not all that difficult. Sometimes I will be standing in front of a shop and the owner will duck back inside as soon as he spots me. Then just when I think, well, no luck here, the owner reappears holding a small child who is holding tightly to a coin until she drops it into my bowl. This has happened frequently over the years and it always makes me feel good about Kyoto. Surely, when the parent himself was once a little boy, his father must have given him a coin to put into some monk's bowl. This is truly one of the wonderful things about this city. One time when I was out walking, I was passing a woman holding an infant who was in turn holding a coin in his hand that was no larger than a leaf of one of those Japanese dwarf maple trees. The infant smiled and let the coin fall into my bowl. Surprised by how young my benefactor was, I asked the woman about the child. She replied that the baby was just forty days old. I was both touched by the loveliness of the gesture and grateful by this woman's very warm spirit of teaching an infant to give money to a monk on takuhatsu. When I was out on takuhatsu one day, a small boy put some dirt into my bowl. I chanted the usual prayer of thanks as I accepted his offering. I was reminded of the story of how a child put sand Shakyamuni Buddha's bowl when he was out on takuhatsu one day. As he was passing near a child who was playing house, the child looked up and immediately gave him one of her sand cakes. Shakyamuni accepted the donation and when he returned to the monastery, during the subsequent work period he had the sand mixed in with the wall plaster. It is said that the boy who put the sand in his bowl became the great king Ashoka in a latter life. Then, a second child came up to me and did the same, and another and another, until five or six children had put dirt in my bowl, which I continued to empty into my bag. And, of course, in front of each child, I recited the same prayer. They were just delighted by all this, although in the back of my mind I was thinking that there were just too many King Ashokas that day. Another day I was on a roll and ten-yen coins were falling in my bowl one after another. Standing in front of a shop, the owner came out and gave me ten yen and I began reciting the prayer of thanks. As I was reciting it, a passerby dropped another ten-yen coin in the bowl and no sooner had I begun the prayer again, when another passerby added ten more yen. Hardly was I finished with these when I turned to face the next person and, bingo, another ten yen. After the donations kept rolling in without a break, I couldn't help myself and I just burst out laughing. As they say, it was the best of times. I feel grateful for being unable to stop laughing over receiving four ten-yen coins. This is a joyful moment for a monk on takuhatsu, especially when there are so many people who have plenty of money and still can't be satisfied. Then again, there were also times like the following. I had been out walking for about an hour and virtually no one looked my way. Every once in a while, someone might toss in a one or two yen coin. After an hour of this, there was barely 30 yen in my bowl. Although it was a lousy route, rarely had it gotten that bad, so I recited my “first comes bad luck, then comes the good” mantra to myself. But good luck never came around, so I finally just went home. Shortly after that, I went to visit my brother at his home. His daughter was pleading with her mother to give her something. I told her not to be so greedy, there are days when I walk around for an hour and only get thirty yen. Surprised to hear such a thing, my sister, who was also there, said, “Oh, I'll donate money for takuhatsu,” and proceeded to give me a thousand yen. Then my brother who heard our conversation from the next room, spoke up, “Hey, me, too,” and came and gave me another thousand yen. The next day when I related this story to a friend, he pitched in and also gave me a thousand yen. So, just about the time I was thinking how strange it was that my thirty yen had now become ¥3,030, an executive heard my tale and added ten thousand yen to the pot! So, my “only thirty yen in one hour” story had now grown to ¥13,030 yen! Who can figure out the meaning of money in the world these days?

Why go out on takuhatsu?

Most of the stories I have related here about takuhatsu don't sound very religious, so I would like to close on a slightly more serious note about why takuhatsu is a vital activity for a person who chooses to live out genuine religious teachings. During all the years I went out on takuhatsu this was always a fundamental question: why go out? As I said before, takuhatsu is a kind of donation collection. There is no merchandise, no product or gift to offset the donation. It is just walking around accepting charity. Because of that, if I were unable to totally accept myself as a beggar, I would have continued to suffer emotionally. Many times, especially when I was neurotic about it, I thought how much easier it would be if I at least had something to exchange, like a door-to-door salesman. I thought of giving up and doing some kind of part-time work. On the other hand, I thought of all the truly religious figures in Buddhist history, beginning with Shakyamuni, who lived by takuhatsu, and the Christians in the Middle Ages, like the Franciscans and Dominicans, who also lived by takuhatsu. I thought there might be a crucial relationship between takuhatsu and religion that I could never really know. If there were some intrinsic reason why a person aspiring to live out a religious life should do takuhatsu, what could it be? I was thinking about this, ten years passed. It was just at the end of that period that I read a book about the scientists who developed the atomic bomb. In 1945, when we first heard that a terrible bomb had laid waste to Hiroshima and Nagasaki, in the midst of all that horror no one could imagine what sort of human beings could have made such an accursed thing. I myself thught that it must have been the work of some inhuman devil who never shed a tear and had only ice in his veins instead of blood. Of course, it turned out that they were not some special breed of animal, they were none other than the nuclear scientists in the vanguard of physics. How could these men have made such a terrible weapon, one that, even now, could very well lead to the complete annihilation of all human beings on this planet? Scientists around the world had raced to be the first ones to make such a bomb, and in the end the Americans had won the race. The horrible result of dropping the bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki pricked the consciences of these top atomic scientists and they wanted to stop further research in this area, so they requested that they be allowed to return to their universities. The American government said they could return to their laboratories, but at the same time the government issued an order to each of the universities not to rehire those scientists. Since all of the science departments at these universities were receiving financial aid from the government, the universities were obligated to follow those orders. Consequently, all the universities turned down the scientists' requests to return and the unfortunate scientists returned to the government facilities and continued their work on new atomic weapons. Thinking about this, I couldn't help but feel the weakness of human beings when confronted with money. That was when I realized the importance of going out on takuhatsu for any person intending to live truly by true religious teachings. Once you receive money from one designated person, you obligate yourself to bow to the money or to its source. Of course, out on takuhatsu, I might have to lower my head several hundred or even a thousand times. Yet even though the amount I receive is just one yen, I am not bowing to the money nor do I have to cavil or get down on my knees. In all the years I have been at Antaiji, I have never solicited a penny from anyone. In that sense, I am my own person. Since Antaiji is a monastery, it has received all sorts of donations. Still, no matter how large or small the amount, to the extent that I haven't solicited it, it is no different from a donation put into my bowl when I am out on takuhatsu. For that reason, it is not necessary to bow and scrape before the money or its source. I have always tried to live my life in accord with religious teachings, although, I am not what anyone would call a Orthodox religionist. I have been able to act this way due to the support I have received through takuhatsu. If you are intending to live out a genuine religious life, then you must learn never to bow before money. And, for that, you must never be afraid of being poor. Once I passed 50, takuhatsu became increasingly difficult for me. Fortunately, my takuhatsu life ended in the spring of 1962, because of the royalties I began to receive from the books I have published on my hobby of origami. I am grateful for that, I have had no teacher or master or boss to bow down before, and the royalties are not something I need to bow to either. In any event, as long as you keep your desires within the parameters of your income, I see no necessity to bow down before Mammon. But if the royalties on my origami books ever dry up so that I no longer have even the bare minimum to support myself, you will see me back out on the streets.

Source: http://www.lastelladelmattino.org/in-english/daitsu-tom-wright/introduction

Cf. Laughter Through the Tears: Kosho Uchiyama Roshi on Life as a Zen Beggar

Daitsu Tom Wright and Jisho Warner co-translated Kosho Uchiyama Roshi's memoir, The Takuhatsu of Laughter Through the Tears, which is excerpted here: http://archive.thebuddhadharma.com/issues/2006/spring/laughterthroughtears.html

To you who has decided to become a Zen monk

By Uchiyama Kōshō rōshi

Translated from Japanese by Muhō Noelke rōshi, abbot of Antaiji

http://www.lastelladelmattino.org/in-english/to-you

The motto for living in the world is: eat or be eaten! Now, if you have decided to become a monk because you think that life in this world is too hard and bitter for you and you would prefer to rather live off other people's donations while drinking your tea – if you want to become a monk just to make a living, then the following is not for you. If you read the following, be aware that it is addressed to someone who has aroused the mind to practice the Buddha way after questioning his own life, and only therefore wants to become a monk.

For someone who has aroused this mind and aspires to practice the way, what is important is to first of all find a good master and look for a good place for practice. In the old days, the practicing monks would put on their straw hats and straw sandals to travel through the whole country in search of a good master and place of practice. Today it is easier to get informations: Collect and check them and decide for a master and community that seems suitable to you.

You should not forget though that to practice the Buddha way means to let go off the self and practice egolessness. To let go off the self and practice egolessness again means to let go off the measuring stick that we are always carrying around with us in our brains. For this, you must follow the teaching of the master and the rules of the place of practice that you have decided for loyally, without stating your own preferences or judgements of good and bad. It is important to first sit through silently in one place for at least ten years.

If, on the other hand, you start to judge the good and bad sides of your master or the place of practice before the first ten years have passed, and you start to think that maybe there is a better master or place somewhere else and go look for it – then you are just following the measuring stick of your own ego, which has absolutely nothing to do with practicing the Buddha way.

Right from the start you have to know clearly that no master is perfect: Any master is just a human being. What is important is your own practice, which has to consist of following the imperfect master as perfectly as possible. If you follow your master in this way, than this practice is the basis on which you can follow yourself. That is why Dogen Zenji says:

To follow the Buddha way means to follow yourself. [Genjokoan]

Following the master, following the sutras – all this means to follow oneself. The sutras are an expression of yourself. The master is YOUR master. When you travel far and wide to meet with masters, that means that you travel far and wide to meet with yourself. When you pick a hundred weeds, you are picking yourself a hundred times. And when you climb ten thousand trees, you are climbing yourself for a ten thousand times. Understand that when you practice in this way, you are practicing yourself. Practicing and understanding thus, you will let go of yourself and get a real taste of yourself for the first time. [Jisho-zanmai]

It is often said that for practicing Zen it is important to find a master – but who decides what a true master is in the first place? Don't you make that decision with the measurement stick of your thoughts (that is: your ego)? As long as you look for the master outside of your own practice, you will only extend your own ego. The master does not exist outside of yourself: the practice of zazen, in which the self becomes the self is the master. That means zazen in which you really let go your thoughts.

Does that mean that it is enough to practice zazen alone without a master at all? No, certainly not. Dogen Zenji himself says in the Jisho-zanmai, just after the quote above:

When you hear that you get a taste of yourself and awake to yourself through yourself, you might jump to the conclusion that you should practice alone, all for yourself, without having a master point the way out for you. That is a big mistake. To think that you can liberate yourself without a master is a heretic opinion that can be traced back to the naturalistic school of philosophy in India.

When you practice all for yourself without a master, you will end up just doing whatever comes into your mind. But that has nothing to do with practicing Buddhism. After all, it is absolutely necessary to first find a good master and to follow him. Fortunately, there are still masters in Japan that transmit the Buddha-Dharma correctly in the form of zazen. Follow such a master without complaining and sit silently for at least ten years. Then, after ten years, sit for another ten years. And then, after twenty years, sit anew for another ten years. If you sit like this throughout thirty years, you will gain a good view over the landscape of zazen – and that means also a good view of the landscape of your own life. Of course that does not mean that thus your practice comes to an end – practice always has to be the practice of your whole life.

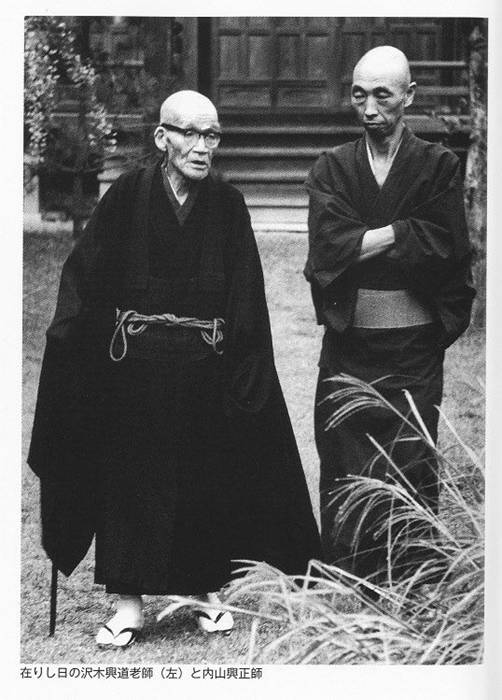

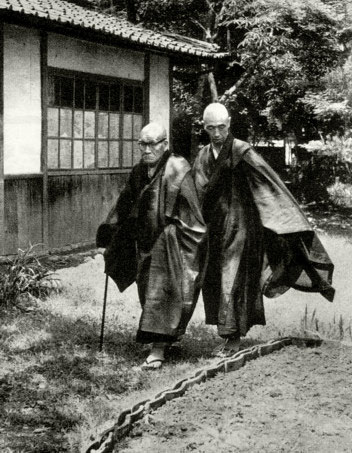

Sawaki & Uchiyama

About the conditions which led to Sawaki Kôdô's greatness

by Uchiyama Kôshô

More than twenty years have gone by since the death of Sawaki Rôshi, a leading figure in the world of Zen who was active from the twenties to 1965. Even today, the immense influence that he has had on our society can be felt. Yet the conditions he was born into were unimaginably difficult and impoverished.

He was born in 1880 in Mie Prefecture. Japan was in the process of reforming itself politically and the new nation still lacked a stable foundation. In those uncertain times, when he was only four years old, his mother passed away, and when he was seven he experienced the sudden death of his father. The four brothers and sisters were divided among the families of relatives or became servants. Sawaki Rôshi, who was called Saikichi as a child, went to an uncle's home. This uncle though also passed away a half-year later, and he was adopted by Sawaki Bunkichi, who officially operated a paper lantern business in the town of Isshinden, but in reality made his money through gambling.

This is where Saikichi spent his four years of primary school. As he started late, he did not finish until he was twelve. The boy worked as an errand boy for his step-parents. He learned about the world of gambling by selling rice cakes in the casinos and keeping an eye on the guest!s sandals. Once he witnessed how a fifty-year old man, who had hired an eighteen-year old prostitute, died from a heart attack, and how his wife came in the next morning crying, “Even in death he has to make things difficult for me – and in a place like this!”

So Saikichi as a young boy had already experienced what happens behind the curtains of our complicated world. Shortly after having finished primary school, a bloody dispute took place between roughly seventy gangsters fighting over the borders of their territories. In the evening, Saikichi's step-father was faced with the unthankful job of establishing contact between the fleeing gangsters. Shaking with fear, he was unable to fulfill his mission. In his place, Saikichi volunteered. In the middle of the night, in a terrible rain, he crossed the scene of the bloody battle and reestablished contact between the gangsters who were already 10 km away. From that night on, his step-father began to fear him and stopped beating him.

Though Sawaki Rôshi spent his childhood years in such a milieu he also had other role models. There was the Morita family, who were scraping out a living in a run-down backhouse. The father glued calligraphy rolls while the son studied traditional Japanese painting. Saikichi felt drawn to this family, whose life, although it took place in the most impoverished conditions, had something very pure about it.

So he began to come and go at the Morita home. He studied old Chinese and Japanese history and literature from the father of the Morita family. Moreover, he learned the truth that there are things in life more important than money, position and fame. Later, Sawaki Rôshi himself said that this was how the bud formed, out of which the fruit of his later life ripened.

After finishing primary school, Saikichi took over the paper lantern business, which was how he fed his hedonistic adoptive parents (his step-mother had been a prostitute). Yet gradually he was beginning to open his eyes to his own life. He began to wonder if it was right to live his life like that and later only marry and feed a wife and children. He didn't know up from down, but his mind clearly yearned for the way.

When he ran away for the first time, Saikichi ended up at the home of an acquaintance in Ôsaka. Yet this escape was unsuccessful: his adoptive parents picked him up again. The next time, he was determined to run so far away that no one would ever be able to catch him again.

As a 16-year old, with three kilos of rice on his shoulders and 27 Sen in his pocket, he marched with the light of a single lantern to Eihei-ji temple in Echizen, constantly chewing on the raw rice throughout the long journey. Eihei-ji could not be bothered with the runaway and Saikichi was refused entry. For two days and two nights, he waited without food or water in front of the gate in the hope that his request would be heard: “Please ordain me as a monk or let me die here before the gates of Eihei-ji.” In the end he was taken in as an assistant in Eihei-ji's workshop. Later he helped out at Ryûun-ji, the temple of a leading priest of Eihei-ji.

At one point he had a day off and decided to do zazen in his own room. By chance, an old parishioner who helped out at the temple entered the room and bowed towards him respectfully as if he were the Buddha himself. This old woman usually just ordered him around like an errand boy, so what was it that moved her to bow towards him with such respect? This was the first time that Sawaki Rôshi realized what noble dignity was inherent in the zazen posture, and he resolved to practice zazen for the rest of his life. In his old age, Sawaki Rôshi often said that he was a man who had wasted his entire life with zazen. The point of departure for this way of life lay in this early event.

Due to various circumstances, his wish to become monk was finally granted and he was ordained in S!oshin-ji in distant Kyu!sh!u. At the age of 19, he entered Ents!u-ji in Tanba as a wandering Zen monk [unsui] but only stayed a fortnight. From there, he was sent to another temple in which he met Fueoka Ry!oun Rôshi. They understood each other well, and Sawaki resolved to follow Fueoka.

Fueoka Rôshi had studied for years under Nishiari Bokuzan Zenji, a great Zen master of the Meiji Era (1868 to 1912), and the longer they were together, the more Sawaki Rôshi was attracted to his straightforward character. Sawaki Rôshi heard lectures from Fueoka Rôshi on Gakudôyôjinshû, Eiheishingi and Zazenyôjinki, which formed the basis of his later practice of shikantaza.

Following that, Sawaki was drafted as a soldier in the Japanese-Russian War (which broke out in 1904) and earned a golden medal. At the age of 26, in the year 1906, he returned to Japan. After the war – rather late for his age – he entered the Academy for Buddhist studies in his home town. After which he transferred to the seminar of Hôryû-ji in Nara where he studied Yogacara philosophy under the abbot Saeki Jôin Sôjô.

At the age of 34, after having obtained this overview of Buddhist teaching, he began to practice zazen alone from morning until night at Jôfuku-ji, an empty temple in Nara. Here shikantaza penetrated his flesh and blood. In 1916, when he was 36, Oka Sôtan Rôshi, recruited him as a teacher for the monks in Daiji-ji in Higo. After Oka Rôshi's death, Sawaki Rôshi lived alone on Mannichi Mountain in Kumamoto and with this as his base, he began to travel to all parts of Japan to give instruction on zazen and hold lectures. When he was 55, he was appointed professor at Komazawa University. At the same time he became godô (a head teacher) at Sôji-ji, one of the two main temples of the Sôtô school. This began the period of Sawaki Rôshi's greatest activity.

At that time, “Zen” didn't mean much more than the kôan Zen of the Rinzai School, but Sawaki Rôshi concentrated entirely on shikantaza as it had been taught by Dôgen Zenji. Looking at the history of Japanese Buddhism, it cannot be overlooked that Sawaki Rôshi was the first in our era to reintroduce shikantaza in its pure form and revive it as being equally valid as kôan Zen.

Because he never lived in his own temple and also did not write any books, people began to name him, “Homeless Kôdô”. Yet in 1963 he lost the strength in his legs and he had to give up traveling. He retired to Antai-ji where he died in 1965 at the age of 85.

For those who seek more information about Sawaki Rôshi's life, there are several Japanese biographies. Here I have only brought together a few snapshots out of his life to give a rough picture to those who know nothing of him. These snapshots present the character of his adoptive step-father and the Morita family, his zazen experience in Ry!uun-ji and his encounter with Fueoka Rôshi – in short, the seed and bud out of which Sawaki Rôshi's life blossomed.

宿なし興道法句参 Yadonashi Kōdō Hokkusan

Excerpts from

The Dharma of "Homeless Kôdô"

by Uchiyama Kôshô Rôshi

PDF: The Zen Teaching of Homeless Kodo

by Uchiyama Kosho & Shohaku Okumura

Final Lesson, by Arthur Braverman

http://buddhismnow.com/2011/10/18/final-lesson-by-arthur-braverman/#more-3684

The Community, by Arthur Braverman

http://buddhismnow.com/2013/10/05/the-community-by-arthur-braverman/#more-6689

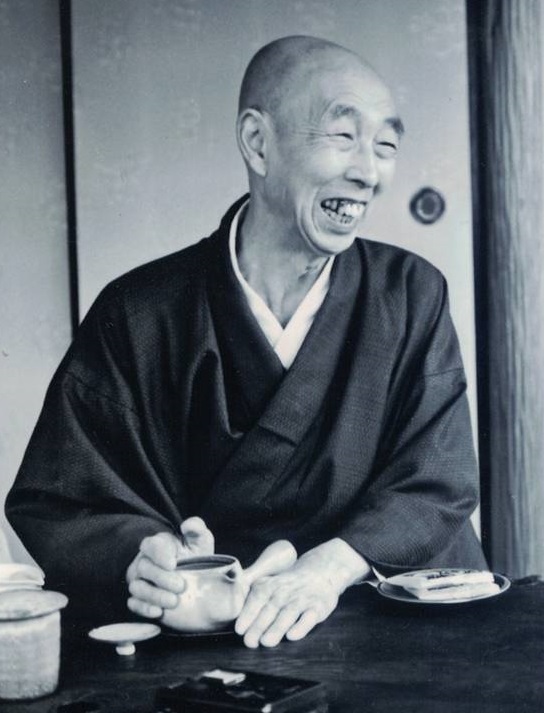

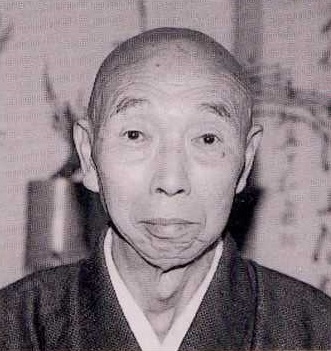

This photo of Uchiyama roshi

was made two days before his death

(いっぽう氏撮影: H10.3.11)

The following poem by Uchiyama Kosho roshi, translated by Daitsu Tom Wright, is based on a passage in the Shobogenzo Genjo Koan that goes:

“To practice the [Buddha]Way is to practice Jiko—all inclusive self.”

http://www.lastelladelmattino.org/in-english/daitsu-tom-wright

If you call, I shall respond

That is just me responding to myself.I can hear all the news of the world

I am just hearing news of myself.When you are in pain or suffering

I lend a hand.That is just me lending a hand to myself.

I follow my teacher and practice (as I am taught)

That is just me following me and practicing.Whatever I bring up, there is nothing apart from Jiko—all inclusive self.

Practicing a Self that is a wholly living Self

That is the samadhi of fully-functioning Self

That is practicing the Buddha Way.

On Zazen

by Uchiyama Kōshō

From:

Shikantaza - an introduction to Zazen

Edited and translated by Shohaku Okumura

Kyoto Soto-Zen Center, 1985In short, doing zazen is to stop doing anything, to face the wall, and to sit, just being yourself that is only the Self. While doing zazen we should refrain from doing anything, yet, being human, we begin to think; we engage in a dialogue with the thoughts in our minds. “I should have sold it that time; no, I should have bought it,” or, “I should have waited for a while.”

If you are a stockbroker you will think like this. If you are a young lover, you may find that your girlfriend inevitably appears all the time. If you are a mother-in-law who doesn't get along with your daughter-in-law, you will think only of your son's wife. Whatever situation you are involved, thoughts will arise of their own accord while you are doing zazen.

Once you realize that you are thinking when you are supposed to be doing nothing, and return to zazen, the thoughts which appeared as clearly before you as if they were pictures on the T.V. screen, disappear as suddenly as if you had switched off the T.V. Only the wall is left in front of you.

For an instant… this is it. This is zazen. Yet again thoughts arise by themselves. Again you return to zazen and they disappear. We simply repeat this; this is called kakusoku (awareness of Reality). The most important point is to repeat this kakusoku billions of times. This is how we should practice zazen.

If we practice in this way we cannot help but realize that our thoughts are really nothing but secretions of the brain. Just as our salivary glands secrete saliva, or as our stomachs secrete gastric juices, so our thoughts are nothing but secretions of the brain.

Usually, however, people do not understand this. When we think “I hate him,” we hate the person, forgetting that the thought is merely a secretion. The hatred occupies our mind, tyrannizing it. By hating the person, we subordinate ourselves to this tyrant. When we love someone we are also swept away by our attachment to this person; we become enslaved by this love. In the end, all of us live as vassals to this lord, thought. This is the source of all our problems.

For example, our stomachs secrete gastric juices in order to digest food. More is not better in this case; if too much is secreted, we may develop an ulcer or even stomach cancer.

Our stomachs secrete gastric juices to keep us alive, but an excess is dangerous. Nowadays, people suffer from an excess of brain-secretions; and furthermore, they allow themselves to be tyrannized by these secretions. This is the cause of all our mistakes.

In Reality, the various thoughts which arise in our minds are nothing but the scenery of the Life of the Self. This scenery exists upon the ground of our Life. As I said earlier, we should not be blind to, or unconscious of, this scenery.

Zazen commands a view of everything as the scenery of the Life of the Self. In ancient Zen texts, this is referred to as “ honchino faku ” (the scenery of original ground).

It is not the case that we become the universal Life as a result of our practice. Each and every one of us receives and lives this universeful-Life. We are one with the whole universe, yet we do not manifest it as the universe in the real sense.

Since our minds are discriminating, we perceive only the tail of the secretions. When we do zazen, we let go of the thoughts, and then the thoughts drop off. That which arises in our minds disappears. There the universeful-Life manifests itself.

Dogen Zenji called it shojo-no-shu , (practice based on enlightenment). The universeful-Life is enlightenment. Based upon that, we practice being the whole universe. This is also called shusho-ichinyo (practice and enlightenment are one.)

We would all prefer happiness to misery, paradise to hell, survival to immediate death. We are thus ever bifurcating Reality, dividing it into something good and something bad, something we like and something we don't. Similarly we discriminate between satori and delusion, and strive to attain satori.

But the reality of the universe is far beyond such an attitude of aversion and attachment. When our attitude is “whichever, whatever, wherever,” then we manifest the whole universe.

In the first place, the attitude of trying to gain something is itself unstable. When you strive to gain satori you are definitely deluded because you desire to escape from a state of delusion.

Dogen Zenji taught that our attitude should be one of practice and diligent work in any situation whatsoever. If we fall into hell, we go through hell; this is the most important attitude to have. If we encounter unhappiness, we should work through it sincerely.

Just sit in the Reality of Life seeing hell and paradise, misery and joy, life and death, all with the same eye. No matter what the situation, we live the life of the Self. We must sit immovably on that foundation. This is essential; this is what “becoming one with the universe” means.

If we divide this universe into two, striving to attain satori and to escape delusion, we are not the whole universe. Happiness and unhappiness, satori and delusion, life and death; see them with the same eye. In every situation the Self lives the life of the Self -- such a self must do itself by itself. This universal Life is the place to which we return.

To you who are still dissatisfied with your zazen

by Uchiyama Kôshô Rôshi

Translated from Japanese by Jesse Haasch and Muhô as part of the book “To you”.

http://antaiji.org/?page_id=72&lang=en

Dôgen Zenji's practice of shikantaza is exactly what my late teacher Sawaki Kôdô Rôshi called the zazen of just sitting. So for me too, true zazen naturally means shikantaza – just sitting. That is to say that we do not practice zazen to have satori experiences, to solve a lot of koans or receive a transmission certificate. Zazen just means to sit.

On the other hand, it is a fact that even among the practitioners of the Japanese Sôtô School, which goes back to its founder Dôgen Zenji, many have had doubts about this zazen. To make their point, they quote passages like these:

I have not visited many Zen monasteries. I simply, with my master Tendo, quietly verified that the eyes are horizontal and the nose is vertical. I cannot be misled by anyone anymore. I have returned home empty-handed. [Eihei Kôroku]

I travelled in Sung China and visited Zen masters in all parts of the country, studying the five houses of Zen. Finally I met my master Nyojo on Taihaku peak, and the great matter of lifelong practice became clear. The great task of a lifetime of practice came to an end. [Shôbôgenzô Bendôwa]

So that's why they say, “Didn't even Dôgen Zenji say that he realized that the eyes are horizontal and the nose vertical, and that the great matter of lifelong practice became clear? What sense could there be when an ordinary person without a trace of satori just sits?”

I remember well carrying around such doubts myself. And I wasn't the only one, a significant number of the Zen practitioners who flocked around Sawaki Rôshi abandoned the zazen of just-sitting in order to try out kenshô Zen or kôan Zen. So I understand this doubt well.