ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

加藤耕山 Katō Kōzan (1876-1971)

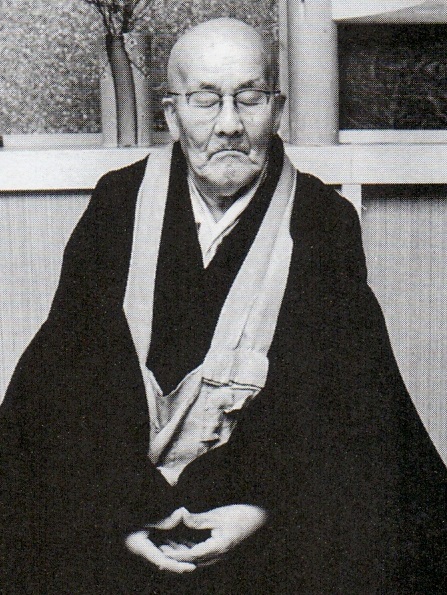

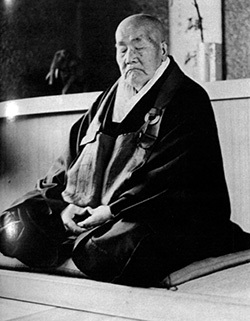

Katō Kōzan sitting in zazen at age ninety-three.

Katō Kōzan on Zazen

http://buddhismnow.com/2014/04/30/our-bodies-are-the-great-universal-life/

When you come right down to it Zen is most important. You can skip a meal once in a while, but you should never forget zazen. If you practise zazen there is that [spiritual] power that comes from the body.

Put your body in order. It will follow naturally that the mind will improve. Mind—body—mind—body—mind . . . Mind and body will always be in harmony.

When you focus on putting your energy into your hara (the lower abdomen), you will function properly whether you are using your hands or your mind. Everything should centre in your hara . . .

The hara is your base. Even learning should be centred in your hara.

Scholar’s studies can become an obstacle, making the mind difficult to control. The effect of zazen is to let your mind and body really listen to you. Quiet sitting is good. Zazen can reasonably be taken as far as one chooses—one can advance by the light discovered within it.

Though I’m 80 [Kôzan was actually 84 when he gave this talk] I haven’t awakened. Even the Buddha is still practising.

. . Only zazen is the real thing—you can’t go wrong. It’s Shakyamuni Buddha as is. There’s no deception in it. It’s a natural need in a human being’s life. It’s the call by the Universe to a human being’s true nature. Zazen perfects the human being.

Even at 92 I still live by zazen. It’s my pleasure, my joy.

Whatever I come across, I resolve through my experience with zazen. When it’s hot it is hot. I feel through zazen that when it’s hot I’m not dissatisfied or in discomfort. Even if there is satori, for example, I must practise zazen. I must continue zazen because [satori] is a momentary dream. It can, after all, pull you around.

Whether you know it or not, zazen will polish the mind and body. Leave satori for later. It is important, but you must do zazen everyday. Even for two or three minutes, you must practise it daily.

(From Ôgon Hempen Zezean Dai Roshi Hôgo [Pieces of Gold: Katô Kôzan Dharma Talks])

PDF: Dharma Brothers Kodo and Tokujoo:

A Historical Novel Based on The Lives of Two Japanese Zen Masters

by Arthur Braverman

Ojai, CA: Taormina Books, 2011. 581 p.

A historical novel based on the lives of two Japanese Zen Masters, 沢木興道 Sawaki Kōdō (1880-1965) and 加藤耕山 Katō Kōzan (1876-1971).

Kodo and Tokujoo is based on the lives of two Japanese Zen Masters, how they grew from two ordinary boys, walking very different paths to become extraordinary men, and the deep spiritual bond between them. It is also the story of Japan from 1880 to 1965, of two personal accounts of Zen journeys to enlightenment, and of love and friendship. The story follows the lives of these two Dharma brothers, set against a backdrop of the Japanese-Russian War of 1905, and the rise of fascism in Japan in the 1930s. Kodo was an orphan, brought up in a harsh environment, while Tokujoo was the son of a well-to-do businessman. They both spent years studying in the most stringent Zen monasteries and became life-long friends. Each struggled to find his way clear of the circumstances in which he had been reared. Each sought a way of life offering more meaning and truth, ultimately becoming a different exemplar of Zen practice and living Buddhism.

https://www.smashwords.com/books/view/174970

http://www.scribd.com/book/194039228/Dharma-Brothers-Kodo-and-Tokujoo

PDF: Living and Dying in Zazen: Five Zen Masters of Modern Japan

by Arthur Braverman

Weatherhill, 2003, 176 p.

[A marvelous book combining the life stories and teachings of five masters - Kodo Sawaki, Sodo Yokoyama, Kozan Kato, Motoko Ikebe, and Kosho Uchiyama.]

INTRODUCTION, pp. 7-10.

In 1969, I traveled to Japan in search of a place to practice Zen Buddhism under the guidance of a Zen master. I was excited to be traveling in the Far East. Many Westerners took to the road in search of alternative ways to live, having been wakened from a state of lethargy when the affluent United States led its people blindly into the Vietnam War. We were an international family bonded by our refusal to buy into a world whose values we didn't share.

Like so many who chose to explore Zen Buddhism as part of an alternative lifestyle, my head was already full of preconceived ideas about what a Zen master should be. I had read what was available on Zen in English at the time, but knew nothing about Buddhism as it was actually practiced in Japan. Little by little my preconceptions were to dissolve as a result of the teachers I met and the community of Westerners and Japanese monks with whom I practiced. The dissolution of those preconceptions was the beginning of real learning for me.

A small community of Westerners came to Kyoto to practice Zen meditation at Antaiji, a temple in a northern suburb of the city. This is a story of those students, Uchiyama Kosho, the abbot of Antaiji, and four other Zen teachers whom I learned of through my connection with Antaiji.

Four of those teachers were priests-three from the Soto Zen sect and one from the Rinzai Zen sect-and one was a laywoman Zen teacher. Each taught their own distinctive brand of Zen, different from the Zen of others and from the teachings of the orthodox Rinzai and Soto Zen establishments of their times. Yet they shared one essential thing: a strong commitment to zazen, or Zen meditation, a true love of the practice that utterly surpassed the lip service given it by so many Zen Buddhist priests in Japan of their day.

Kosho Uchiyama, abbot of Antaiji, is the central figure in this story. Uchiyama was a Soto Zen priest who created an atmosphere at Antaiji that welcomed people from all walks of life to practice Zen meditation. Many Westerners found their way to Antaiji as a result of Uchiyama's openness. Perhaps the best-known of the Zen teachers I have focused on is Kodo Sawaki, Uchiyama's teacher and a maverick Zen master who traveled the country preaching zazen. Though Sawaki was officially the abbot of Antaiji during the latter part of his life, he never actually took charge of a temple and was nicknamed "Homeless Kodo." Sawaki is also the human link that connects each teacher to the others.

Sodo Yokoyama was a lone monk who spent his days sifting in zazen, playing songs by blowing on a leaf, and brushing poems that he composed in his "temple"- a public park he visited daily. He was a disciple of Sawaki for over thirty years. Kozan Kato was a close friend of Sawaki and the only Rinzai Zen master in the group. He became known in Japan in his ninety-fourth year when a Japanese Buddhist teacher and scholar published a taped account by Kozan of his life and Zen philosophy. His total disregard for fame earned Sawaki's respect.

Motoko Ikebe, a laywoman disciple of Uchiyama, is the sole woman Zen teacher in my story. This was a feat in itself in the overwhelmingly male-dominated world of Japanese Zen. She lived a simple life in a country village in Hyogo Prefecture, and her quiet demeanor and strongly charismatic presence attracted many students to seek her guidance. She had them all practice zazen and advised in many other aspects of their lives as well.

As I set these stories down, I found myself writing more and more about my relationship with Uchiyama and the community of Zen students with whom I practiced. Many of the anecdotes recount how we lived and practiced around Antaiji, and may not be directly related to formal Zen meditation practice; what they do show is how a group of people who came to Japan to study Zen llved and worked and played while trying to maintain a meditation schedule created by Uchiyama at Antaiji.

Like our teacher, we believed in the inherent wisdom of meditation practice but we also realized that following that practice did not make us "special." For Uchiyama, practicing Zen was not something people did in a vacuum, in a protected environment free of the demands of the world around them. He wanted his monks to devote ten years to monastic practice before returning to Japanese society, but he also believed that, even while they were training at Antaiji, they should not be completely isolated from life outside of the monastery. He was happy to have Western men and women practicing at Antaiji, believing that the cross-cultural contact would be good for the monks as well as the Westerners. And he never encouraged any of the Westerners to take monastic vows, though some did. Uchiyama wished to eradicate the exotic and the mystic from Zen practice and show us that Zen was life in the world- but with a greater degree of sanity.

When I lived at Antaiji during my first months in Japan, there were Sunday zazen meetings for the local Japanese lay community. One man, who spoke some English and probably wanted to practice it, struck up a conversation with me. What he told me illustrates the atmosphere Uchiyama hoped to create for his students. "When I met the Roshi in a private meeting yesterday," he said, "I told him that I sit zazen for an hour in the morning and an hour in the evening. I then asked him if there was anything else I should be doing as a lay Buddhist practitioner. He said to me, 'You should be a good father and a good husband."

In an attempt to give the readers a more complete picture of my subjects, I have tried to tell their stories from as many different perspectives as possible, drawing freely on a wide variety of materials, first-person and otherwise, in English and Japanese. For example, I have told the story of Soda Yokoyama, the poet-monk who composed music that he played on a leaf, through the eyes of many different people. Some, like his brother-disciple Uchiyama, wrote articles about him, and I've included samples of them. Yokoyama also told his own story in a book of his collected writings edited by his only disciple, Joko Shibata; I've included excerpts from that collection as well. And finally, my meeting with Yokoyama and interview with his disciple, Shibata, many years later, add to the picture, providing a comprehensive and multifaceted description of this remarkable man.

Uchiyama's distinct approach to Zen set the tone for practice at Antaiji and the attitudes of his students. Those who preferred other ways of practice left; those that stayed were of a certain bent. Like the teachers in the book, we believed in the importance of Zen meditation above all other aspects of Zen Buddhism. We also valued a certain amount of independence in our lives. Life at and around Antaiji under the guidance of Uchiyama allowed us to pursue both our commitment to meditation and our personal freedom.

Zazen was the focus of all the teachers in this story. Their faith in it and their stress on it over other aspects of Buddhism (though they certainly did not disregard those other aspects) is the common link here. I have attempted to give a picture of as many aspects of the lives of the teachers, the community and the temple as possible, but the essential story is that of five Zen masters living and dying in zazen

KŌZAN KATŌ RŌSHI

pp. 92-111.How can I describe a priest as enigmatic as Kōzan Katō? He is the only Zen teacher

in this story who went through Rinzai Zen training--at the strictest Zen monastery

of the time, to boot--and came out with nothing but praise for the brutal treatment he

received. In fact, he praised just about everything, though nothing more highly or with

greater vigor than zazen.

Moreover, Katō's teaching is not severe at all. He gets people to do zazen because his

love for the practice is infectious. In every photo of him except those capturing him doing

zazen or practicing calligraphy, his toothless mouth is open wide in laughter. He is the

reincarnation of Hotei, the laughing Buddha.

I am listening to tapes that Katō's son Taigan sent me of hisfather lecturing at a

zazen meeting at the temple of a disciple in northern Japan. The trip was a long one and

Katō was ninety years old at the time. Though I call these "lectures," they certainly don't

resemble any traditional Zen Buddhist lecture.

Katō begins: "Well, now, it's like ... since I've reached my ninetieth year, I'm getting

more and more feeble ...." After some more stammering, he continues, "My old lady

said to me, 'Give it up,' trying to stop me from coming. She said, 'It's really dangerous.

You can hardly hear and you've become quite feeble. You'd better not go. You'll only end

up being a burden on everyone.'"

Then he talked about the joy of being ninety, knowing this might be his last year of

life, and he suggested that everyone practice zazen as a farewell to him.

Katō is truly uncomfortable lecturing, so he just rambles. But when students ask him

questions about zazen or Buddhism at the end of the meeting, the rambling stops. He

becomes sharp and clear.

"Do zazen. It is not difficult. Zazen is the most important thing in a person's life. Do it

everyday and you will see. Zazen is not something done only when you cross your legs. You

have to do zazen that is not separated from your daily life. Whatever you do, don't lose the

composure that you felt when you did zazen. Your daily life should be based on the order

that comes from zazen--the feeling of regulating the body and mind. It must work in your

life. Do it for five minutes or three minutes, but do it everyday. Make it a habit."

His voice is soft and joyful. If Sawaki is yang, Katō is yin. There is a Buddhist

expression "rōba Zen," or "grandmotherly Zen. " There is no better expression of the Zen

of this twentieth-century Hotei.

LIVING IN ZAZEN [坐禅に生きる Zazen ni ikiru]The story, as I heard it from a Buddhist scholar named Kiyoshi Hoshi, was that

Ryūmin Akizuki, Zen priest and scholar, went to Zeze-an, Katō's temple in

Okutama, Tokyo, with a small hidden tape recorder. He listened to Katō, who was

ninety-four years old at the time, tell the story of his life, and then he brought home

the recording and transcribed it. This record was subsequently published as Living

in Zazen [坐禅に生きる Zazen ni ikiru]. The story of the hidden tape recorder may have

been fabricated to add to Katō's mystique, but his story is compelling enough without

this preface, for it is also the history of Japanese Zen in the early twentieth century.I was born in the Kurozasa Mountains in Mikawa. I left my hometown

when my father went to Nagoya to start a sake-making business. I was

named Sanjirō and was the fourth of ten children.

My father's sake business failed. When I was nine years old, a new

bridge was completed in some distant place and I was taken to the

festivities in celebration of the event. I was then dropped off at a temple

and left there. The temple was a mile or so from my house, so I couldn't

return home. I thought something was peculiar when my father had my

head shaved before we left home for the festivities. I'd become a novice

monk at the Zen temple Daieiji north of Nagoya, but not as a result of any

personal aspiration. My father had deceived me, making me a prisoner

of the temple.Katō opens the account of his life by de-romanticizing his relationship to Buddhism;

the anecdote also shows that his faith grew out of his practice and not from any

initial belief.

His early life at the temple, especially his studies, was painful.After having been given over to the temple, I was hardly ever permitted to

go to school. Instead, I had to learn Chinese classics by rote. This was a

long time ago [probably between 1885 and 1890]. Three of us-- an old lady and two

novice monks-- used to gather around a paper lantern. The old lady spun cotton and

the two of us sat along side her and studied. We read sutras and the Chinese classics.

The Chinese characters in them were difficult for young elementary-school

students, but we managed to learn them. If we didn't memorize them, we

got bopped on the head .... Putting all our energy into memorization,

we lagged behind in our ability to reason. We understood none of the

meaning of the text; we simply memorized how to read the characters. We

learned according to the proverb, "read mechanically one hundred times

and the meaning will come through." After we had made some progress,

we had to read the Lotus Sutra. The Chinese characters in this sutra are

extremely difficult. It took many years and was a painful experience but we

finally memorized it. The process bordered on brutality.Despite Katō's claim that his ability to reason lagged, he continues by describing

how argumentative he became. He even told the head priest of the temple to study

modem science to familiarize himself with contemporary thought. They would

argue, he said, until the priest ended it with the his usual, "Get the hell out of

here."

Kato dressed in Western clothing even when he went to parishioners' homes

to read sutras. He was proud of his liberal ideas and believed he was in complete

accord with the progressive trends in religion of that period, but upon reflection

he said, "When I think back on those days, [I feel so embarrassed] I break out in a

cold sweat."

Though Katō criticized the temple and his teacher, he did learn from the head

priest and became emotionally dependent on him. When the head priest died, Katō

fell apart. "My mind was scattered," he said, "and I became physically unhealthy; I

couldn't sleep at night."

Then he was advised by another monk to practice zazen. Katō was in his early

twenties, living in Tokyo at the time, and on this monk's advice he went to Engakuji

Temple.Sōen 5haku Roshi had returned to Engakuji from America to high acclaim.

I went to Engakuji to practice Zen meditation under him. I went there as

a layman, not a monk. Sōen had a new style, giving sanzen (interviews)

sitting on a chair by a table.

I had kenshō after being with Sōen only one week. This upset my

Zen practice. I tried two or three check points (sassho) and was able to

solve them through thinking. Then I started to have doubts. As long as I

continued meeting with the teacher, I would pass koans one by one. It was

that easy. According to the practice at Engakuji, it was best to do zazen

for a short period of time and advance through all the koans within three

years. Then you were to study, study, study. If you weren't a good scholar,

you received very little attention. I wasn't satisfied with that. Having

had a satori so quickly, I had no interest in it. I'd originally been a Sōtō

monk and had read Buddhist texts. I had practiced a little too. So with

some hint, I quickly understood, and the feeling, "Aha! This is it!" would

immediately surface. In the end it was through thinking that I progressed

with koans. It didn't deserve to be called Zen. Even studying Buddhist

texts and doctrine was better than this kind of halfhearted practice. This

was intellectual Zen. I wanted to practice more deeply so I left.For the next few years Katō described himself as being lost. He returned to his

hometown and through his family's wealth and influence (you could buy temples

then, according to Katō) he inherited a temple. Seeing no relationship between life

as a temple priest and true Buddhism, he eventually abandoned his temple. He had

come across Dōgen's Zuimonki in a bookstore in Nagoya, and he made up his mind

to follow the path of zazen. Enduring the wrath of his parents for abandoning the

temple they had acquired for him, he set out in search of a place to practice zazen.

The security of his own parish, which his parents felt was his passport to a place in

society, he saw as an obstacle to a life devoted to zazen.

"At that time there were no Sōtō zendōs where zazen was really being practiced,

so I had to go to a Rinzai monastery," Katō recalled. He chose Shōgenji in Ibuka,

Minokamo City, Gifu Prefecture, because it was known for the severity of its

practice. Having no experience with Rinzai monasteries or the etiquette required

there, he spent one night on the way to Ibuka at a small Rinzai temple. He learned

all he could from the monk in charge, and set out the next day for Shōgenji. He

arrived while a ceremony was being held for its founder. Katō helped out at the

ceremony and when it was over, he had to go through the formal "niwa zume"

(confinement in the garden).Though it was only a formality, I had to remain in a prostrate position

and wasn't allowed to raise my head. I put my surplice (kesa) on the

ground and placed my head on it. Since the only thing required of me

was that I keep this position, I could have slept. Still, to remain prostrate

in the garden all day is quite painful. Once in a while I would go to relieve

myself. I'd take off my robe and lay it down neatly and would go to the

toilet-- that was allowed, so I could take my time and relax. By evening

someone would come and say, "Get out!" They usually refuse your

request to stay. The monk would say, "No use practicing here, there are

better places to practice. Go to one of them!" He'd then beat me while I

was prostrate and drive me out with the keisaku. l'd leave and then come

right back. Since this was all a formality, he was waiting for me to return.

Even now, I believe, niwa zume still exists in most monasteries.

When this was over, I was thrown in a room and kept in a kind of

solitary confinement. This practice is called tanga zume. There they

watched my every move. It was designed for that. They put me in that

room and peeped in to observe my behavior, to see if I remained calm

and composed. Had I panicked or acted strangely rather than seriously

engaging in zazen, they'd have dragged me out of there. This went on for

about three days. It was rather easy because I didn't have to do any work.

As long as I did zazen, everything was fine. After this I was allowed to sit

in the zendō as one of the monks.Katō goes on to explain the philosophy behind some of these severe Zen monastic

practices.Once you were accepted in the zendō, you were no longer subject to being

beaten and thrown out. They would only revert to that if you did something

wrong, disobeyed, or talked back to them. You were required to listen even

if what they said was unreasonable. A feudal attitude prevailed there. If you

were told by a senior to do something, or to do something in a particular

way, you were expected to say yes and go along with it. That's practice.

It's getting rid of the ego. If you say this or that, you are responding from

a self-centered point of view. The primary objective is to rid you of self-

centeredness. There actually is meaning in it after all. At any rate you were

never allowed to express your own opinion. You were required to follow

this kind of discipline for the first one or two years.Brian Victoria's book Zen at War made me aware of the degree to which this feudal

attitude that Katō appears to have supported may have been a product of a military

spirit that many Zen Buddhist priests and Zen organizations adhered to. One result

of this attitude in the Zen world was to aid the Japanese government by giving them

a philosophical foundation to support their suppression of dissent as they marched

their country to war in the 1930s.

The impression I got of Katō as a result of reading his dharma talks and records

of conversations with friends and disciples, however, was of a man with great ability

for self-reflection. While his resolve to practice the Way was firm, he was able to

laugh at his own foolishness and at his early mistaken views of Buddhism. But right

to the end he believed in a Zen method in which the novice must be completely

subordinate to his superior. He considered his superiors good people who had his

best intentions at heart.

In his case, that may have been so, but in the political arena, when the term "holy

war" was being used to muster support for Japanese military aggression abroad,

Katō seems to have been unwilling to cast aside his personal opinions and lend his

support to the government-- at least when advising his disciples. When counseling

his student, Kōen Kureyama, who was on his way to serve in the military during

World War II, he said, "When you kill someone, you can't say it is for a holy war.

Never take part in this senseless killing."

Katō talked about the counterproductive effect his knack for solving koans had

on his practice: "Shaku Sōen Roshi's recognition of my kenshō was extremely bad

for me. Because of that, I didn't follow through to the end. You really must follow

through to the end." Though he went to Shōgenji with the intention of doing just

that, and though he felt great respect for Dōshū, Shōgenji's Roshi, he once more

found koans easy to solve intellectually and again became discouraged and quit. He

decided to just sit, without attending dokusans, and he did so for five years. Later,

however, he described the decision to just sit until he experienced a true realization

as "another self-centered point of view."

Though upon reflection later he saw his behavior at this time as childish and self-

centered, to the monks at Shōgenji he appeared to be growing in stature. Ironically,

his attachment to his own idea of the meaning of Buddhist practice, which caused

him to withdraw from the regular monastery routine, led those around him to

regard him as a superior monk.Within only five years, I had to deal with the problem of being called

upon to be one of the top monastery functionaries. Everyone around me

insisted that I take the position, so I had no choice but to leave. I'd asked

myself what it would mean to be in charge; would that make me a genuine

monk? My ideas were quite inflexible [as to what real Zen practice was]

when I left Ibuka [Shōgenji]. I decided to go into the mountains alone and

do zazen until I penetrated to its core. As I look at it now, I see it too as

another fixed idea.After leaving Shōgenji, Katō spent the next two years at a nearby mountain, Hazama.

There was a valley, a waterfall, and a shrine for ascetics. Though he doesn't say why,

after two years on Mount Hazama he left his mountain retreat and went to Eiheiji

for the annual lectures on the writings of Dogen, There he became friends with a

senior monk named Kanryō. Ryoei Mizuno, the roshi in charge of Yōsenji, a temple

in Matsuzaka City, Mie Prefecture, was a visiting lecturer at the meeting. Mizuno,

a scholar-monk who had spent years in America, asked Kanryō and Katō to take

charge of his training center. Mizuno felt that since the two of them had trained in

Rinzai monasteries, they would train his monks in a strict Rinzai style. Katō wasn't

anxious to go but submitted to his respected friend's wishes. Kanryō had completed

the Rinzai koan practice and, Katō, though ambivalent about koans, was strongly

influenced by him.

Katō describes Kanryō as "very talented, sharp as a razor, and an able poet." His

respect for his friend's bearing and ability made him take Kanryō's advice seriously.

The men had similar backgrounds, having switched from Sōtō to Rinzai Zen, but

Katō seemed on the verge of giving up Rinzai practice, too. The two friends often

debated the value of koans, with Kanryō recommending Katō follow through to

the end. Katō retorted that there was no meaning in a practice that you can grasp

through the intellectual process. Kanryō accused him of holding on to his own

opinions. He said Katō couldn't judge koans because he hadn't followed through on

them. Then he said something that caught Katō's attention. He said, "Even if it is

worthless, complete the practice as though you were throwing things on a garbage

heap, but do complete it."

Kanryō talked about an extraordinary Zen master named Sanshōken, at Bairinji

in Kyūshū. He recommended that Katō study with him. Having been so impressed

by his friend's statement about throwing things on a garbage heap, Katō made a

complete turnaround: "All right," I said, "then I'll follow through to the end as

though I were throwing things on a garbage heap."

It was at this time that Katō became friends with Kōdō Sawaki, who was assistant

head of training at Yōsenji. The two monks spent long hours together talking about

Zen and developing a friendship that was to last a half a century. Katō and Sawaki

talked about leaving Yōsenji, both agreeing that it was not a place for serious

practitioners. But Sawaki was astonished at how little time his friend wasted after

making his decision to leave. "I was taken by surprise," he was to remark later,

"and heard no more of him. Seventeen years later I saw him walking in downtown

Kurume with a torn umbrella. I learned then of his journey to Bairinji."KATŌ GOES TO BAIRINJI [梅林寺]

If Katō was looking for a place where his intellectual grasp of koans wouldn't help

him, he found it in Bairinji.

Katō was forty when he arrived at Bairinji. At training monasteries seniority was

based not on chronological age but on when you arrived at the monastery. He had

to swallow his pride and tolerate reprimands from monks as young as seventeen

years old who had arrived before him. Monks of petty natures frequently used this

rule to lord it over others. One such monk, who had come to Bairinji a year before

Katō, always referred to him as "old monk" and ordered him around and scolded

him mercilessly. Katō managed to control himself, but just barely. He had come to

Bairinji to study under Sanshōken, of whom his friend Kanryō spoke so highly, and

he didn't want to spoil his chance to do so. Bairinji was proud of its reputation as a

"devil" monastery with harsh discipline, and Katō had to exert great effort to control

his feelings.I'd come to Bairinji to study under Sanshōken [Yūzen Gentatsu, 1842-1918]. Though

I still held to my own cocky opinion about the meaninglessness of koans, I'd come

to Bairinji because Kanryō said I should meet the Roshi. But Sanshoken

had already retired and the new teacher was Komushitsu. Sanshoken

lived in an elegant retreat on the other side of the garden near the river.

Only during rohatsu sesshin [a practice period held near December 8,

traditionally regarded as the day of the Buddha's enlightenment] did

he have koan interviews with the practicing monks. At other times

newcomers were not able to approach him. Having come with the

intention of meeting him, I found this difficult to bear. The new teacher

appeared somewhat unimpressive.The following story of Katō's first rōhatsu sesshin at Bairinji describes some rather

brutal behavior. It's important to keep in mind that Katō, who is the recipient of this

vicious treatment, considered the lesson one of the most valuable in his career as a

Zen practitioner.When the first rōhatsu sesshin came, I told myself not to pass up

the opportunity and rushed out [to dokusan], taking the lead. It was

interesting how everyone tried to be first, as though it was a race. At

Shōgenji, the monks were reluctant to go to dokusan; they clung to their

cushions, and the monk in charge had to drag them from their cushions

and make them go. But at Bairinji the monks rushed ahead noisily in

what one can only call an ill-mannered fashion. As their slippers flew,

they rushed out to form a queue to go to the dokusan room. It was a

strange practice. I dashed forward like the others and took a front seat in

line because, as I said before, I felt I had to see Sanshōken. If I was late, I

feared, I might not get the chance.

While we waited in line, an assistant surveyed all of us. He resembled

a demon as he came over to me, grabbed me by the neck, and looked at

my face. He then said, "Dokusan with Sanshōken is too good for you."

Holding me by the neck in front of everyone, he said, "He's too good for

you, the new teacher will be just fine." Then he dragged me out.

I thought to myself, "You shithead, I'm not a beginner," but it didn't

matter how I felt.

"Get out of here, he's too good for you," he repeated and started

beating me with the keisaku. I had to give up and leave. "Well," I thought,

"I'll just have to wait until next year." I was really incensed. I did eventually

start having dokusan with Sanshōken, but it didn't last very long.

At rōhatsu sesshin the assistants get very worked up and they train

the new monks very severely. I thought I appeared humble, but, because

of my age--l was already forty years old--they assumed I traveled the

monastery circuit for the fun of it. It was not unusual to come across guys

like that at Zen monasteries. Though I wasn't that type, they thought I

was. So they decided that if they didn't train me severely, I would become

difficult to deal with in the end. Consequently, I was trained in my first

sesshin with excessive harshness.

Had I merely been beaten, I could have put up with it. At rōhatsu

everyone, including lay students, sat in rows. The assistant attacked me

with abusive language from the start: "It's useless at age forty to put on

airs as though you were enlightened!" That really hurt. "Damn it, you

young squirt," I thought. Then he said: "I'll give you a taste of thirty blows

from a disciple of Sanshōken!" I thought to myself, "What the hell are

you talking about?" but I could do nothing. Then he started hitting me.

He actually hit me thirty times. It was a wonder I didn't faint. The keisaku

broke in half and went flying. I kept the broken parts for a long time to

remember the incident, but now I don't know what I did with them.

Everyone was not treated this way. I was hit thirty or forty times. It

was just right for me. I felt as if a heavy burden had been lifted from

me. I still feel grateful for that today. I guess, up to that point, being

already forty, I had reasoned things out and thought that I had a little

insight into Buddhism. I grasped it [Buddhism) in my own way, but I

feel my understanding at the time was really little more than my own

self-centered thinking after all. Because I had this strange proclivity, I felt

relieved when I was hit. The fellow who hit me was named Kyōsu; he was

an exceptional fellow of imposing force.Katō continued to explain why he thought the beating was important in emptying

him of what he referred to as his tendency to "look down on others." He said he

often thanked Kyōsu for being responsible for his change.

Another reason Katō valued the fierce intensity of this rōhatsu sesshin was its

effect on the new breed of intellectual monks. Many young monks had attended

university, and Katō felt that, like himself when he was younger, they depended

too much on intellectual processes in their practice. He felt the rough treatment

at rōhatsu helped shake these "philosopher monks" out of their tendency to try to

think their way through practice.In the zendō, the assistant roshi would tell you to go to dokusan. You'd

be sitting and he'd say, "Go to dokusan." When you did, there would be

five or six assistants waiting at the garden. "What are you doing hanging

around here?" they'd say. "Does it make any sense to flounder around in

front of Roshi? Go back and sit resolutely. Go back to the zendō and sit."

Then you'd go back to the zendō and you'd get yelled at by the assistant

roshi and thrown out. So you'd collect yourself and try again, and once

again you'd be greeted by, "What the hell are you doing here?" Such

treatment is a form of violence. If it were one or two guys it wouldn't be

so bad, but there were four or five, some with judo black belts. In the end

you were desperate, and it no longer mattered how threatening they were

or how much of a beating you took. You had no choice.

You didn't see this kind of behavior in other zendōs. Not in Kyoto, not

even in Shōgenji, the other "devil" monastery. At Shōgenji, they'd drag

you out of the zendō. Those who didn't want to leave would be forcefully

pushed out. They'd cling to something in the room and refuse to leave

and a bunch of senior monks would come and drag them out. And you

weren't allowed to go outside the main gate, so eventually you'd make

your way to dokusan. That was the extent of the discipline. That is the way

students were trained in all monasteries. But in Bairinji it was different. If

they just said sit, I would have sat no matter how long, but they squeezed

you from both sides. On one side they said go and on the other side they

said don't go. It was impossible.Katō goes on to say how if you were new to the monastery, in your first or second year,

you really felt that the monks were devils, but in the bath after sesshin these same

devils scrubbed your back and rubbed you down, praising you for practicing hard and

later serving you rice gruel. You'd forget the anger you had for them. He added that he

realized this kind of rough treatment was wrong, but he felt that humans who didn't

have to bear the bitter with the sweet didn't really develop fully: "People today say that

this kind of violence is unnecessary, that ways resembling those of the military should

be abolished. They argue that we should acquire understanding peacefully. But it

never happens [solely] that way. In order to reach people with different backgrounds

and different living situations, you need both."

There are monasteries where such harassment and even violence is a smoke

screen hiding a lack of genuine understanding. I was allowed to sit sesshin in a large

Rinzai monastery in Kyoto a few years ago where I was certain that the expression

of violence was an indication of a lack of true religious feeling on the part of the

monks. I witnessed a young monk who couldn't stay awake and whose nervousness

resulted in many errors of temple protocol get smacked around by senior monks

whose intention, no doubt, was to discipline him. What struck me, however, was the

anger these monks displayed and their lack of awareness that this young man was

physically and emotionally weak and was unlikely to learn from such treatment.

I met the teacher, who was kind enough to allow me to participate in the

session even though I was an outsider, after the sesshin was over and presented

my observations to him, being careful not to be accusatory, which would certainly

have been counterproductive. He explained to me that there will inevitably be some

rough play when the tension of sesshin starts getting to the participants, but that

the intention was to teach the new monks, and that severe methods were only for

the purpose of furthering that goal. I then asked if it were proper for a head monk

to jump in the air and throw a kick at the chest of a novice who was nodding. His

expression changed dramatically. He quickly responded that there were prescribed

methods for waking a nodding student and that a flying kick was certainly not one of

them. I felt certain from the look on his face that he was going to confront the head

monk of that training period, and I hoped it would have an effect.

Katō became a disciple of Kōmushitsu [香夢室], a small, subdued man, who in Katō's

words "was skillful at obsequious bowing." Kōmushitsu appeared the antithesis of

his teacher, Sanshōken, a tall, husky man with a jovial and dynamic personality.

At first Katō was devastated at losing the chance to study with Sanshōken, and he

contemplated leaving Bairinji. But he stayed on, and after studying with Kōmushitsu

he was to conclude that this man who first appeared to him "insignificant" was "the

perfect teacher for me."

Though, as mentioned previously, inka shōmei, or "certification," is thought

of in America as proof of the attainment of enlightenment, it is given in Japan to

legitimize a teacher's right to be in charge of a training monastery. At least that

was the reason one received it at Bairinji. You had to complete your koan training

to receive inka, but you didn't necessarily receive inka just because you completed

that training.

Kōmushitsu never received inka shōmei from his teacher. Sanshōken said

there was no need to do so because he was nearby and could always testify as to

Kōmushitsu's right to teach. Sanshōken had given inka to two other students who

were teaching at other monasteries, but there were others who, though having

completed their training with him, never received inka. He clearly didn't like the

ceremony and avoided it when he could. When Sanshōken died, Kōmushitsu still

hadn't received inka from the master and refused to continue teaching at Bairinji

without this official certification. In order to rectify this situation, Mokurai Takeda

[竹田黙雷 1854-1930], Zen master of Kenninji Monastery and recipient of one of

the two inka shōmei Sanshōken did bestow, performed the inka ceremony, passing it

on to Kōmushitsu in order to keep him from leaving Bairinji.

1) 香夢室 Kōmushitsu; 2) 三生軒 Sanshōken [猷禅玄達 Yūzen Gentatsu], 1842-1918; 3) 竹田黙雷 Takeda Mokurai, 1854-1930Katō talked about the difficulty with inka--that some who receive it become

complacent. He felt that if you were serious about practice, you would always be

stretching yourself. "You know when you have the real inka," he wrote. "Another

person can never really know whether you have experienced awakening. Roshi told

me I have experienced it, but I know it's still incomplete. Inka means only that

you've completed your koan training, and it is necessary, on a certain level, to certify

this. But the most important thing is your feeling 'this is it,' the feeling of 'great

peace,' which is the objective of Zen practice. If you receive inka and you don't feel

the peace, it's meaningless."

Katō was quite clear about his own degree of attainment: it wasn't complete, he

still had to train. But he also felt that those who thought they no longer needed to

train were probably fooling themselves.Since I'm not much good at anything else, I've come this far professing

the one road, "zazen, zazen." But I realize that death is right before

me. Aware that things are still incomplete, I have to be vigilant and sit

zazen. But however I look at it, I don't think much will happen. On the

other hand, it's all right because whatever happens there's always some

dissatisfaction. When you build a house, it's no good to make it without

any gaps. You should always leave something unfinished. That's the way

it is: "If it's full, it will spill over." It's the same with people. If you think

you are complete, then there is nothing ahead except death.Compared to his charismatic teacher Sanshōken, Kōmushitsu might be described as

someone of no import. Once Katō made the decision to study under him, however,

he had the opportunity to see his teacher's true worth and to appreciate what had

previously appeared to him as the behavior of a man of little consequence.

Kōmushitsu was fastidious in the extreme. It was said that he would use every

drop of water three times before pouring it out.When people wash their face they simply discard the water ... but he

[Kōrnushitsu] was the kind of person who had a precise way in which

he wanted everything done. You rarely find people like him. He often

talked about Dōgen Zenji, and I think he was perfectly in accord with the

meritorious conduct ofthe ancients described in the "Gyōji" (Maintaining

Practice) chapter of Dōgen's Shōbōgenzō. I was by his side all the time

and I know him well: he wouldn't let a drop of water spill.Katō described how Kōmushitsu used rags until they were reduced to shreds,

employing them for different tasks at different stages of their deterioration; how he

had a place for everything and knew immediately if something was missing; and

how he noticed and commented on everything Katō did. Once he stopped Katō from

sweeping away a spider's web because he said the spider was showing him its art.

Kōmushitsu never discarded anything that was at all useable. Katō quotes him as

saying, "Every object has a life, and its true nature is to preserve its life."I served as Kōmushitsu's attendant for a long time, assisting him in many

ways. I felt veneration when I saw the care with which he did his work,

but when you are by his side he can be quite annoying. It's not that he

berated you, but you felt as though you were always being watched. When

I started serving him, even spreading out futons was a demanding task. I

would naturally spread them out my own way, and he would say, "I have

my way, watch me," and he would start. "You spread the bottom futon

[the one that serves as the mattress], then you fold it over again and cover

it with the upper futon [the one that serves as the cover]. You shouldn't

stand on the bottom futon." That's true. It's improper to stand on the

futon of an esteemed person. He repeated, "You shouldn't step on it. If it

were for me it wouldn't matter, but when you are preparing the bedding

for a respected person, you should never stand on it. That's why you

spread it out first, then fold it in half, then cover it with the upper futon,

fold it and then spread both."Katō goes on to describe Kōmushitsu's comments on his way of hanging a mosquito

net, preparing pickles, and doing just about everything else: never scolding, just

watching and then saying, "I have my way of doing it." He felt sorry for his teacher

having to eat the same meager vegetarian fare day in and day out, and he went out

and bought some fried tofu for a treat. But he could never mention to Kōrnushitsu

that he bought it; he'd have to tell him that someone came by and donated it to

the temple. Even then he would get a lecture about how eating special foods at the

monastery takes the joy out of eating outside when invited.

Though Komushitsu was quite talkative around his students, Katō told of how

uncomfortable his teacher was when he went out to another temple for a big

Buddhist ceremony and had to sit in the seat for esteemed guests. While all the

other monks were a little tipsy from drinking and engaged in frivolous conversation,

Kōmushitsu would turn to the alcove and practice zazen.

What impressed Katō most about his teacher was the way he seemed to have

transcended the desires for name and fame. Even when he was the abbot of Bairinji,

he lived simply. While his teacher was alive, he played the role of junior partner,

taking care of all the details while Sanshōken carried out all the public business of the

monastery. When Sanshōken was living in a retreat house, having retired from temple

duties, Kōmushitsu attended to the monks, giving dokusan until nine in the evening

and then going to care for his teacher. During the hot months he would massage and

fan Sanshōken until he fell asleep. He did it, in Katō's words, "because filial piety was

simply a part of him, without any feeling that he was doing something [special]."

Though Kōmushitsu was in charge of Bairinji, he refused to wear robes that

designated that position as long as his teacher was alive. He felt that he was simply

acting in his teacher's stead as a natural part of his service.

Katō had come to Bairinji having practiced with a number of Zen teachers, both

Rinzai and Sōtō. None of them impressed him enough to encourage him to stay

with them. Although some, like Sōen Shaku, may not have been right for him, a

bigger part of the problem, as Kanryō pointed out to him, was his unwillingness

to let go of his own ideas. Kanryō thought that a dynamic teacher like Sanshōken

might help Katō recognize his own role in his unsuccessful search for a teacher

and a suitable practice. It's quite possible that the dynamic Sanshōken might have

disappointed Katō in the end; dynamism can pale with familiarity. Kōmushitsu, on

the other hand, small and unimpressive as he appeared on first contact, had a depth

that kept Katō reaching to try to understand. Katō needed this, and once he realized

that fact, his real training began.

After four and a half years at Bairinji, Katō was put in charge of a temple near

the monastery. For fifteen years he continued to meet with his teacher daily for

dokusan.

At some time during this period Katō married. Unfortunately, he doesn't talk

about why he got married, though that information would certainly provide us

more insight into his life during this period. Marriage didn't disqualify him for

appointment as abbot of Bairinji, but it certainly lowered the chances. According

to his biographer Ryūmin Akizuki, some years later, despite his marriage, Katō

was offered the position of abbot of Bairinji and of another large Rinzai monastery,

Daisenji. He refused both.

Katō left Kyushu for Tokyo at the age of fifty-nine. A Bairinji friend, Shūgen

Nakajima, invited him to live in what he was led to believe was a large temple.

Katō took his friend up on his offer. When he arrived, he found an old abandoned

temple falling apart from years of neglect. With the help of his friend Kōdō Sawaki,

the willingness to work, and the energy of one far younger than his years, Katō

managed to rebuild the temple and survive there for the next thirty-five years.You ask why I came here. There is a temple nearby called Ryūjūin. The

priest in charge of the temple was trained at Bairinji. He begged me to

come here. I thought, "Well, maybe," and decided to try it. That was 1934.

I was fifty-nine then.

"There's this temple," he said, "waiting for you. You have nothing to

worry about; just come." So I arrived with a look of confidence, and what

do you think I found?--a temple abandoned for twenty years, in a terribly

decayed and dilapidated state.Katō contacted the parish requesting permission to live there, despite the condition

of the place, and was refused. The parishioners thought that he, approaching sixty,

was too old. He went to meet the parish representatives, displaying all the vigor of a

twenty-year old: '''What are you talking about?' I said. 'I'm not ready for my funeral.

I've been practicing up to now and my life is just beginning.' Hearing me out, they

came to the conclusion that I 'still had a lot of spunk left.' And I responded, 'I have

no choice.' After that they let me live at Tokuunin.'

But Katō had no intention of being abbot: "When I went to the parish leaders

I told them that I hate the thought of being in charge of the temple, and I didn't

want to be an abbot. I said, 'But I'd like to plant plum trees throughout the temple

grounds. I'll be abbot of the plum trees."

He farmed, planted trees, and practiced zazen. With time, a small group formed

that practiced with him, and he conducted dokusan for them. He didn't like to

lecture, however, so he didn't. His strength was in encouraging others to practice.

Like his friend Sawaki, he had tremendous faith in the power of zazen. Of all the

teachers featured in this book, he was most insistent on zazen's importance.I don't lecture because it has no effect. I don't know the first thing

about lecturing. It's different for scholars and distinguished men such

as Mumon Yamada. All I do is sit with you and carry the keisaku stick. I

don't get tired because this is the only thing I know.

I constantly say that everything is the same; nothing is separate. I

mean all is one. Of course this is just theory. Many things appear--loss

and gain, for example--but still, if you reflect that originally they were

one, you won't become attached. Even when someone slights you, if

you reflect on your relationship with others being originally one, you will

go to the heart of the matter. But no matter how much you understand

the reasoning, if you haven't grasped it with your gut, you can't respond

properly. If you practice Zen wholeheartedly you will get it; you must

cultivate the energy to erase the illusion [of duality]. You approach Zen

through objects; by objects I mean form and practice.Katō's philosophy is simple: everything is originally one. Returning to that

understanding is, for him, "right living." The method to reaching that understanding

is zazen. He practiced zazen for over sixty years and he did not feel deceived.Even three or five minutes [of zazen] done each morning will become

a habit. It will feel good. When you wash your hands after going to the

toilet, it feels good, doesn't it? If you don't wash, it doesn't feel good ....

When I don't do zazen it doesn't feel right. That's the feeling I'd like you

to develop. It's not very difficult.

If you forget to practice, it's like a person forgetting who he is, like a

person forgetting his self-esteem or his value. If you see yourself as a

person who has within himself the invaluable power to move the world,

you won't go wrong. When you don't believe in yourself, you feel like a

lowly insect.

Through zazen, you will realize your own worth. The Buddha referred to

those who have accomplished this as "perfect personalities," and they are.Katō's emphasis on concentrating your energy in the tanden. (lower abdomen),

is particularly characteristic of his Rinzai Zen study. Sawaki talks about putting

your mind in the tanden, but not with the same emphasis as Katō. Uchiyama and

Yokoyama, Sawaki's chief disciples, say little if anything about it.The lower abdomen is the center of all the nerves. The abdomen

controls the entire body. Zazen maintains the posture in which [energy]

is concentrated in the lower abdomen. When you sit, your energy goes

to the abdomen and controls the entire body. When you think trivial

thoughts, your energy goes to your head. When you concentrate it in

your lower abdomen, the energy doesn't fragment--it all becomes one,

the whole universe settles there. You are one with the world; your source

is the same as that of heaven and earth, and your body is the body of

all things. The object of Buddhism is to perfect the person, the body-

mind. There is no Buddha outside of the human being, which means it

[Buddhism] perfects the universe.For a long time after Katō completed his own intensive training at Bairinji, he

worked with a few students who had considerable monastic experience. Some of

them were sent to him from Bairinji to spend a few years honing their practice. He

seems to have kept a low profile for two reasons: he was very serious about training,

and he was basically a shy man. But his reclusive nature is the one thing for which

he expressed regret, saying that if he could do it over again he would shout zazen

from the rooftops and announce it over the airwaves.When I think about my time spent here, I realize that I have failed. I've

blundered for a long time. Though I've connected with some people like

Yanase [Yanase was one of Katō's two dharma heirs], I haven't allowed

the general public to approach me. I didn't have time for them. Among

the people who visited, there were those who were suitable to this place

and I naturally related to that special few, ignoring the general public.

That's not what Buddhism is about. I realize that I should have been relating

to the local farmers and other parishioners after all. Now when I tell those

people, "Zazen is good for you, come sit with me," nobody comes. They

think it's something very difficult.

I have to work hard to get people of our country to practice zazen. That

is my cherished wish now.

When I ask kids after they've practiced zazen what they feel, they say

they feel good. That's because their minds are working. It's best with

children. With young children I make it like a game. With seven- and

eight-year olds, when I take one thing from a group of objects and ask

them to guess which one I've picked, they usually guess correctly. Adults,

on the other hand, can't, because of their delusions. If they were to empty

their minds, they would guess correctly without thinking.Sit with your legs crossed, back straight, and breathe deeply while pushing your

lower abdomen out--that would probably be how Katō would advise someone to sit

in zazen. Katō was known for his protruding lower abdomen, which was especially

prominent because he had a small, thin physique. His many years of putting a

slight pressure in this area during zazen caused the protrusion. He was proud of his

stomach, but when he watched sumo wrestlers, huge men with enormous bellies,

he said that he had met his match.

These physical constraints in the zazen posture, Katō said, allow you to return to

your original state. Infants, he continued, naturally breathe deeply from the lower

abdomen. As they grow, bad habits develop. Posture starts to droop and abdominal

breathing gives way to thoracic (chest) breathing. Zazen is training to return to

your natural state. Breaking habits developed over many years requires great effort,

but, according to Katō, the effort is well worth it. He attributed his long life to the

practice of zazen.

Katō talked about being round shouldered when he started sitting and having

straightened up as a result of zazen. But, he said, proper posture and correct

breathing are not enough. If effort is not made to remain aware of yourself and your

environment--that is, if you sit up straight but in a mental fog--your zazen has no

meaning. There are people, he insisted, who are in perfect accord with the zazen

state who have never practiced formal zazen. This, he claimed is because zazen is

not anything unusual. It is the natural, inherent path of wisdom.

Katō was ninety-four when he made these reflections. Though they are remarkably

clear for a man of his age, some of his statements are rather extreme. He suggested,

for example, that zazen be a required subject in schools from kindergarten through

university, and that no one be graduated unless they had completed the zazen

requirement.

When responding to Akizuki's question about death, Katō said that when he

felt death near he planned to sit and refrain from eating. At that time, he added, he

would like someone to put a sign outside the entrance of the zendō with the words,

"Still Practicing."

According to Akizuki, on January 31, 1971, Katō fell over and died while in the

seated posture. He was ninety-six years old.

Kōzan Katō, farmer monk and teacher of Zen masters of some of the largest

monasteries in Japan, spent the last three decades of his life in a small temple in a

suburb of Tokyo. He taught a small group of students, raised a family, planted trees,

farmed, and drank tea with his neighbors.

To his neighbors he was the wise, affectionate priest of Tokuunin, the poor

temple down the road. To a small circle of monks who had some contact with

Bairinji, he was an important teacher from the Bairinji lineage. To Kōdō Sawaki he

was a respected friend and companion in zazen.

He struggled in poverty to feed his family and continue his life as a Buddhist

practitioner, but his joy was infectious. He said that as he looked back on his life he

realized that his most trying times were the best. He had few regrets.

"When it's hot," he said, "go outside and work as hard as you can. Then go into

your house and practice zazen. The cool breeze you will feel is not a result of any

man-made invention [like a fan]. The coolness will naturally come from the depth

of your belly. It will be as if you entered a cool room. That's the way you have to

approach hardship. If you endure your suffering, it will be the seed of joy."

Despite Katō's praise for the value of the severe training he went through and

the spare life he chose for himself, he was neither dogmatic nor impractical. One of

his students relates the following encounter with Katō some days before the Roshi's

death. A neighbor of this student made honey for a living. Receiving some of the

honey, he went to Tokuunin to share it with his teacher. He found Katō lying down.

After the usual greeting, Katō said to him, "I'm going on an extended fast." When

asked why, Katō responded, "I've always wanted to get everyone in this country to

practice zazen. I thought that if I fasted, it might even reach the ears of the emperor,

eventually having the benefit of urging everyone to do zazen." The student then

said, "You have many advanced disciples. They can spread the teaching of the Way.

Leave it to them and today try some of this honey I've brought."

The Roshi sat up and said, "Good point," and he started to lick the honey.

It was Katō's ability not only to laugh in the face of adversity but also to see true

value in all experiences that gave him a joyous aura that drew so many to him. His

joyous presence and his positive worldview blasted away all doubts and sadness.

Whether this power he exercised was a result of zazen or not, it made those who

met him want to try the practice he recommended so enthusiastically and find out

for themselves.