ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

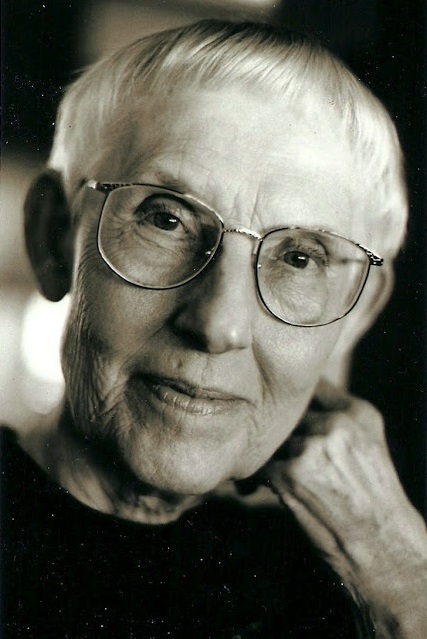

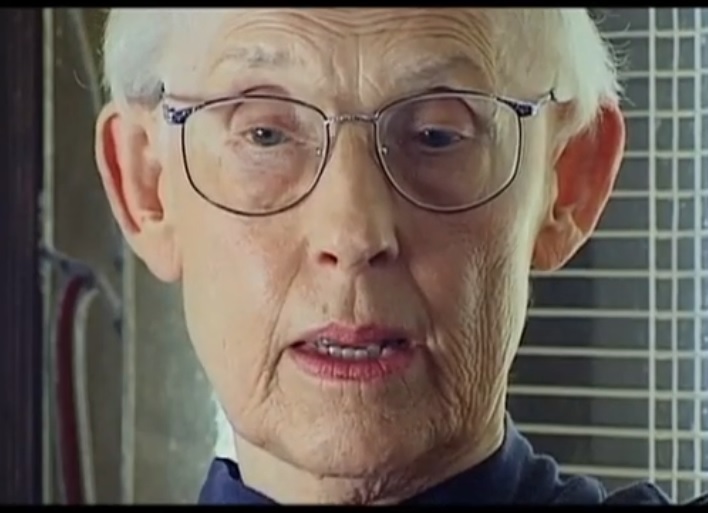

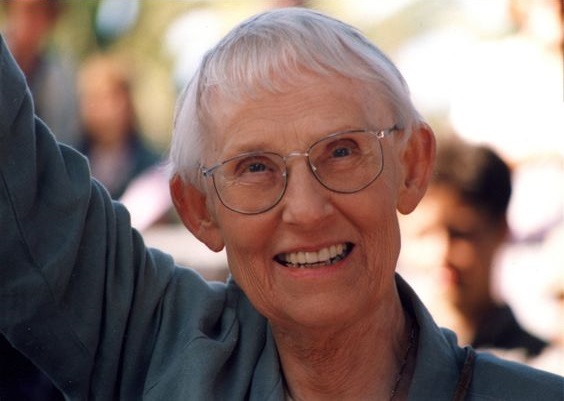

Charlotte Joko Beck (1917-2011)

シャーロン・浄光・ベック

Born in New Jersey, she studied music at the Oberlin Conservatory of Music and worked for some time as a pianist and piano teacher. She married and raised a family of four children, then separated from her husband and worked as a teacher, secretary, and assistant in a university department. She began Zen practice in her 40s with 前角 (大山) 博雄 Maezumi (Taizan) Hakuyū (1931-1995) in Los Angeles, and later with 安谷 (白雲) 量衡 Yasutani (Hakuun) Ryōkō (1885-1973) and 中川宋淵 Nakagawa Sōen (1907-1984). Having received Dharma transmission from Taizan Maezumi Roshi, she opened the Zen Center San Diego in 1983, serving as its head teacher until July 2006.

Her Dharma name: 浄光 Jōkō = Pure Light.

Books:

PDF: Everyday Zen: Love and Work (1989) > PDF: pp. 1-45.

by Charlotte Joko Beck (edited by Steve Smith)

http://www.academia.edu/36699947/Charlotte_joko_beck_everyday_zen

https://extrafilespace.files.wordpress.com/2017/05/charlotte-joko-beck-everyday-zen.pdf

https://www.amazon.ca/Soyez-zen-BECK-CHARLOTTE-JOKO/dp/2266078801 Soyez Zen

http://www.zenroma.it/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Zen-quotidiano.pdf Zen quotidiano

http://bomnalssi.tistory.com/910 샬럿 조코 백 [가만히 앉다]Contents

Preface

AcknowledgmentsI. BEGINNINGS

Beginning Zen Practice

Practicing This Very Moment

Authority

The Bottleneck of FearII. PRACTICE

What Practice Is Not

What Practice Is

The Fire of Attention

Pushing for Enlightenment Experiences

The Price of Practice

The Reward of PracticeIII. FEELINGS

A Bigger Container

Opening Pandora’s Box

“Do Not Be Angry”

False Fear

No Hope

LoveIV. RELATIONSHIPS

The Search

Practicing with Relationships

Experiencing and Behavior

Relationships Don’t Work

Relationship Is Not to Each OtherV. SUFFERING

True Suffering and False Suffering

Renunciation

It’s OK

Tragedy

The Observing SelfVI. IDEALS

Running in Place

Aspiration and Expectation

Seeing Through the Superstructure

Prisoners of Fear

Great ExpectationsVII. BOUNDARIES

The Razor’s Edge

New Jersey Does Not Exist

Religion

EnlightenmentVIII. CHOICES

From Problems to Decisions

Turning Point

Shut the Door

CommitmentIX. SERVICE

Thy Will Be Done

No Exchange

The Parable of Mushin

PDF: Teaching Zen to Americans by Kim Boykin (2010)

Philip Kapleau's The Three Pillars of Zen, Shunryu Suzuki's Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind, Charlotte Joko Beck's Everyday Zen

PDF: Nothing Special: Living Zen (1993) > PDF

by Charlotte Joko Beck with Steve Smith

http://www.slideshare.net/ankeny/nothing-special-living-zen-10212248 E-book

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dw3wv657gtQ A film by Claudia Willke

https://4grandesverdades.files.wordpress.com/2009/12/nada-de-especial-vivendo-zen-charlotte-joko-beck.pdf Nada de Especial

https://www.amazon.fr/Vivre-zen-Charlotte-Joko-Beck/dp/2266078437 Vivre ZenContents

Epigraph

PrefaceI. Struggle

Whirlpools and Stagnant Waters

The Cocoon of Pain

Sisyphus and the Burden of Life

Responding to Pressure

The BaseboardII. Sacrifice

Sacrifice and Victims

The Promise That Is Never Kept

Justice

Forgiveness

The Talk Nobody Wants To Hear

The Eye of the HurricaneIII. Separation and Connection

Can Anything Hurt Us?

The Subject-Object Problem

Integration

The Tomato Fighters

Do Not JudgeIV. Change

Preparing the Ground

Experiences and Experiencing

The Icy Couch

Melting Ice Cubes

The Castle and the MoatV. Awareness

The Paradox of Awareness

Coming to Our Senses

Attention Means Attention

False Generalizations

Listening to the BodyVI. Freedom

The Six Stages of Practice

Curiosity and Obsession

Transformation

The Natural ManVII. Wonder

The Fall

The Sound of a Dove—and a Critical Voice

Joy

Chaos and WonderVIII. Nothing Special

From Drama to No Drama

Simple Mind

Dorothy and the Locked Door

Wandering in the Desert

Practice Is Giving

PDF: Now Zen (1995)

by Charlotte Joko Beck ; edited by Steve Smith.

The essays in this work were originally published in Everyday Zen (San Francisco, 1989) and Nothing Special (San Francisco, 1993), by Charlotte Joko Beck with Steve Smith.

“Beginning Zen Practice” and “Practicing with Relationships” are revised versions of talks copyrighted by the Zen Center of Los Angeles.Contents

Preface vii

ONE Root

Beginning Zen Practice 2

Prisoners of Fear 9

What Practice Is 19TWO Stem

Whirlpools and Stagnant Waters 34

Experiences and Experiencing 41

Practicing with Relationships 50THREE Flower

Simple Mind 68

Joy 73Notes 83

PDF: Ordinary wonder: Zen life and practice (2021)

Contents

Foreword by Jan Chozen Bays

Introduction by Brenda Beck HessPART ONE: EXPERIENCE

The Only Thing We Need to Know

What Do You Really Want?

Just Snow, Just Now

Up, Down, and the Space In-Between

Noticing and BeingPART TWO: THE CORE BELIEF

That Icy Couch

See What You Do

Our Central Work

The Nature of the Self

Practice Is About Your Life

Cutting Off the Escape

Life Is Not a ThingPART THREE: THE WORK

A War Within

Grasping Nothing, Discarding Nothing

No Effort, Tremendous Effort

What Is Practice?

What We Hold in the Body

Everyone Is Practicing

The Way Things Should BePART FOUR: EMOTION

Anger and Other Bricks

See Your Complaint

Nothing to Forgive

The Gateless GatePART FIVE: CONFIDENCE

Meet the Parsnips

99.4% of Our Problems

The Vastness and the Peanut Butter

Getting WetPART SIX: RELATIONSHIP

Going into the Dark

Authentic Relationships

The Other Side of the Mountain

A Dagger Passing ThroughPART SEVEN: WONDER

Far from Shore

Do Good

Narrow Is the WayAfterword by Brenda Beck Hess

Charlotte Joko Beck in Hospice

Shambhala SunSpace published an interview with Charlotte Joko Beck, conducted by Donna Rockwell.

http://www.shambhalasun.com/index.php?option=content&task=view&id=1613

http://www.oxherding.com/my_weblog/2011/06/charlotte-joko-beck-in-hospice.html

http://prairiezen.org/Members/comings_and_goings.html

How old were you when you started meditating?

Charlotte Joko Beck: Thirty-nine, forty, somewhere in there.

Did you have any realization through meditation?

No. Of course we have realizations, but that's not really what drives practice.

Will you say more about that?

I meet all sorts of people who've had all sorts of experiences and they're still confused and not doing very well in their life. Experiences are not enough. My students learn that if they have so-called experiences, I really don't care much about hearing about them. I just tell them, “Yeah, that's O.K. Don't hold onto it. And how are you getting along with your mother?” Otherwise, they get stuck there. It's not the important thing in practice.

And may I ask you what is?

Learning how to deal with one's personal, egotistic self. That's the work. Very, very difficult.

There seems to be a payoff, though, because you feel alive instead of dead.

I wouldn't say a payoff. You're returning to the source, you might say - what you always were, but which was severely covered by your core belief and all its systems. And when those get weaker, you do feel joy. I mean, then it's no big deal to do the dishes and clean up the house and go to work and things like that.

Doing the dishes is a great meditation — especially if you hate it…

Well, if your mind wanders to other things while you're doing the dishes, just return it to the dishes. Meditation isn't something special. It's not a special way of being. It's simply being aware of what is going on.

Doesn't sitting meditation prepare the ground to do that?

Sure. It gives you the strength to face the more complex things in your life. You're not meeting anything much when you're sitting except your little mind. That's relatively easy when compared to some of the complex situations we have to live our way through. Sitting gives you the ability to work with your life.

I read your books.

Oh you read. Well, give up reading, O.K.?

Give up reading your books?

Well, they're all right. Read them once and that's enough. Books are useful. But some people read for fifty years, you know. And they haven't begun their practice.

How would you describe self-discovery?

You're really just an ongoing set of events: boom, boom, boom, boom, boom, one after the other. The awareness is keeping up with those events, seeing your life unfolding as it is, not your ideas of it, not your pictures of it. See what I mean?

How would you define meditation?

Awareness of what is, mentally, physically.

Can you please complete the following sentences for me? “The experience of meditation is…”

“…awareness of what is.”

“Meditative awareness has changed my life in the following way…”

“It has changed my life in the direction of it being more harmonious, more satisfactory, more joyful and more useful probably.” Though I don't think much in those terms. I don't wake up in the morning thinking I'm going to be useful. I really think about what I'm going to have for breakfast.”

“The one thing awareness has taught me that I want to share with all people is that…”

I don't want to share anything with all people.

Who do you want to share with?

Nobody. I just live my life. I don't go around wanting to share something. That's extra.

Could you talk about that a little bit?

Well, there's a little shade of piety that creeps into practice. You know, “I have this wonderful practice, I want to share it with everyone.” There's an error in that. You could probably figure it out yourself.

I think that's something I need to learn.

You and I know there's nothing that's going to make me run away faster than somebody who comes around and wants to be helpful. You know what I mean? I don't want people to be helpful to me. I just want to live my own life.

Do you think you share yourself?

Yeah, but who's that?

Charlotte Joko Beck

By Adam Tebbe

June 15, 2011

https://web.archive.org/web/20180415090612/http://sweepingzen.com/charlotte-joko-beck-dies-at-94-american-zen-pioneer/

Charlotte Joko Beck, Zen teacher, author and founder of the Ordinary Mind Zen School, has died peacefully today, June 15, 2011 at 7:30 a.m., at age 94.

Born on March 27, 1917 in New Jersey, Beck studied at Oberlin Conservatory of Music and taught piano for a time. She married and raised four children before separating from her husband and working as a teacher, secretary and assistant in a university department. She came to Zen practice in her forties and studied with the late Hakuyu Taizan Maezumi roshi. For many years she commuted between San Diego and Los Angeles to practice with the roshi. Of her experiences, Beck said in an interview with Shambhala SunSpace, “I meet all sorts of people who've had all sorts of experiences and they're still confused and not doing very well in their life. Experiences are not enough. My students learn that if they have so-called experiences, I really don't care much about hearing about them. I just tell them, “Yeah, that's O.K. Don't hold onto it. And how are you getting along with your mother?” Otherwise, they get stuck there. It's not the important thing in practice.” Asked what is the important thing in practice, she replied, “Learning how to deal with one's personal, egotistic self. That's the work. Very, very difficult.”

Joko Beck also studied with both Haku'un Yasutani roshi and Soen Nakagawa roshi. She became one of Maezumi's twelve Dharma successors in 1978 and went on to establish the Zen Center of San Diego in 1983 (where she served as head teacher until July, 2006). She is the founder of the Ordinary Mind Zen School, a loose fit organization of her Dharma successors which is non-hierarchical. As a teacher of Zen, Joko Beck was free from the patriarchal trappings of Japanese Zen. Joko's approach to Zen teaching was greatly informed by Western culture, and she discontinued shaving her head, seldom wore robes and seldom used titles.

Joko was the author of two very important books that are frequently recommended by interviewees at Sweeping Zen— Everyday Zen (1989) and Nothing Special (1993). Her first book, Everyday Zen, is a book in which she described what meditation is and, more importantly, what it is not. Author Ruthann Russo writes, “…she says it is not about producing psychological change, achieving some blissful state, cultivating special powers or personal power, or having nice or happy feelings. She does say that meditation practice is simple, and it's about ourselves. To practice effectively, we need to remove ourselves from all external stimuli. Then we experience reality, which is challenging for most of us.”

Her second book, Nothing Special, is, as Maezumi himself once remarked, very special. In it Joko expresses what is the original essence of Zen—unencumbered by some of the formal practices and activities we've come to associate with Zen practice over the years. For Joko, Zen is simply being right here in the moment, with nothing extra. Zen practice will yield us nothing other than this moment. In the book she answers her students questions and helps highlight, again, what Zen practice is really about. She says, “Practice has to be a process of endless disappointment. We have to see that everything we demand (and even get) eventually disappoints us. This discovery is our teacher.”

In 2011 Joko began eating less and was rapidly losing weight. Her family placed her under the care of hospice. She is survived by her four children: Eric, Helen, Greg (Dharma name Tando) and Brenda (Dharma name Chiko).

Dharma successor Barry Magid says, “One of her great virtues as a teacher was that she did not try to clone herself. She let us digest her teaching and grow in our own different directions. Her Dharma seeds are scattered far and wide. They will go on sprouting in ways we cannot predict and cross-fertilize with other lineages. The Ordinary Mind School may grow or wither, but her influence is now everywhere.”

According to the Twitter account of fellow Zen teacher Joan Halifax, Beck's last words were,”This too is wonder.”

The Pools

by Charlotte Joko Beck

[The text of "The Pools" has been reprinted from February & March 1989 issues of

the Newsletter of the Zen Center of San Diego.]

Let's picture if we can two landscapes. The first has a deep clear quiet pool, and the second also has a deep clear quiet pool. The first one is surrounded by garbage. The second one, also surrounded by garbage, has an odd characteristic - everyone who jumps into the pool takes a little pile of garbage in with him -- and there is something in the pool that eats it up, so it remains quiet and clear.

Which kind of practice are you doing? Most of us long for deep, blissful sitting and, even if our pool of peace is ringed around with garbage, we attempt not notice it; if the garbage can disturb us, we want to ignore it. We don't like difficulties; we prefer to sit in our peace and not be intruded upon. That's one type of sitting.

The other kind of pool eats up the garbage; as fast as it appears, it is consumed as the person entering the pool carries it in with him. Still in a short time the pool is clear and undisturbed. It may churn more at first. The major difference is that the first pool ends up with more and more garbage around it; the second has none or very little.

As has been said, most of us long for the first kind of practice (life). But the second, facing life as it is, is more genuine; we keep churning up our drama -- seeing it, experiencing it, swallowing it -- throwing the garbage into ourselves, the deep pool that we are.

A practice exclusively devoted to concentration (shutting out all but the object of concentration) is the first pool. Very peaceful, very seductive. But when you climb out of the pool, the garbage of life remains -- our dualistic dealings with our work and relationships. You haven't handled them. Or you may resort to the well-intentioned but inaccurate devices of positive thinking or affirmations; the gas in the garbage increases and in time explodes.

The second pool (being each moment of life, pleasant or unpleasant) is at times a slow and frustrating practice, but in the long run, fruitful and satisfying. With all that as a background, let's look at what can be called the turning point in our life and practice. From what are we turning? Let's look at some sentences: "I feel irritated. I feel annoyed. I feel happy." What we omit is: "I feel I am hurt by you. I feel I have been made happy by you."

Actually, the fact is not that you irritate me; it's that I have a desire to be irritated. You may loudly protest, "Oh, never, I certainly don't want to feel irritated or hurt..." Well, just for a few years (intelligently, in the second pool). The first and uncomfortable years of sitting make it clearer and clearer that my desire is to be irritated or angry (separate). That's almost all I have known as a means to preserve and protect what I think is my identity. With continued awareness, it dawns that there is only one person who can irritate me or make me feel lonely and depressed, and it is I -- myself as a false identity.

We begin to see a strange and lethal truth: contrary to our beliefs, our basic drive and all our life fore goes into a struggle to perpetuate our separateness, our touchiness, or self-righteousness.

Lao Tzu said, "He who feels punctured, must be a balloon.” the balloon of irritability, anger, self-centered opinions. If we can be punctured (hurt), we can be sure we are still a balloon. We want to be a balloon; otherwise we could not be punctured. But our greatest desire is to keep the balloon inflated. After all, it's me!

So what would turning be? What is the turning point? It begins when we observe and feel our anger, our manipulation, and our anxiety - and know in our hearts a deep determination to be in another mode.

Than the real transformation can begin. Instead of ignoring garbage, pushing it away, or wallowing in it, we take our garbage into ourselves and let it digest. We take ourselves with us into the pool of life. This begins the turning. After it, life is never the same.

The turning is at first feeble and intermittent. Over time, it becomes stronger and more insistent (in Christian terms, the 'hound of haven' chases us). As it strengthens, more and more we know who our Master is. Of course, the Master is not a thing or a person but our awakening knowledge of Who We Are. The difficult years of practice (and life) come before the turning. The patience and skill of both teacher and student are called on to the utmost. Some but not all will make it through the difficulties.

Gurdjieff said: man is a machine. We know how machines work: when the blender's button is pushed, it goes WHOOSSSH; when we turn our car's ignition key, the motor roars. Man is a machine. Why? As long as a man's primary drive is to keep his balloon unpunctured, to avoid having his buttons pushed, he is an automatic machine which has no choice.

Even moving from passive dependence to an active and angry independence -- "Don't tell me what to do!" -- is still the activity of a machine with buttons. I feel ruled and compelled by 'something else'; I have no choice. Like the blender, if pushed, I turn on.

Suppose you do something to me that I view as punishing (it's mean, it's unfair, and I don't deserve it). How do I react when this button is pushed? With anger? (And I may not reveal my anger, or I may turn it against myself). Then I am a machine. In this instance, what would the tuning point be?

The turning point is my ability, developed slowly by practice, to be aware of the thoughts and bodily sensations which comprise anger. In the observing of thoughts and sensations, anger will swallow itself and its energy can open life instead of destroying it. Then I (the angry one) can act out of this clarity in a manner that benefits me and you. This is the way of the second pool; the one that takes the garbage, and digests it, letting it feed and renews life as compost does a garden.

Let us not have some naive notion that this ability is won overnight. A lifetime is more like it. Nevertheless, faithful and determined practice makes a difference and fairly soon at that.

We come to view the unpleasant aspects of life as learning opportunities. If my balloon is deflated a little -- great! As an opportunity to be welcomed, not avoided or dramatized. Each round of such practice renders us a little less machine-like, gives us more appreciation of ourselves and others.

Let's live in the second pool.

Dharma Lineage

Ōsaka's lineage

|

Kuroda's lineage |

Harada-Yasutani's lineage |

↓

Charlotte Joko Beck (1917-2011); Dharma name: 浄光 Jōkō = Pure Light