ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

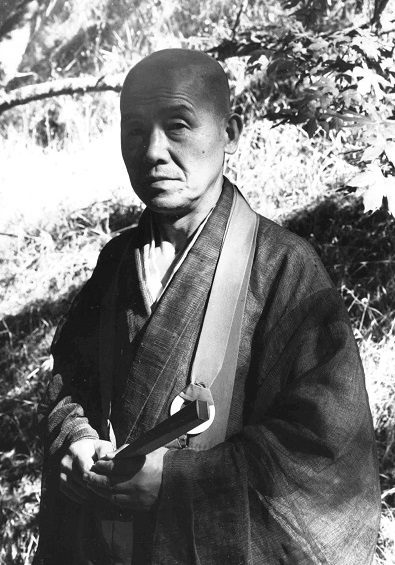

中川宋淵 Nakagawa Sōen (1907-1984)

Dharma name: 宋淵玄珠 Sōen Genju

Tartalom |

Contents |

Két idézet Terebess Gábor fordításában:

Nakagava Szóen haikui |

Two quotations from Nakagawa roshi:

PDF: Endless Vow: The Zen Path of Soen Nakagawa |

Nakagawa Soen (1907-1984) Pen name: Mitta-kutsu, Ryu-sanjin, Ryuou. Dharma transmission from Genpo Yamamoto. He became the abbot of Ryutaku-ji in 1951. He went to the USA 12 times and contributed to the spread Zen in the world. He also made efforts to found Sobo-ji in New York and Daibosatsu Zendo Kongo-ji in New York State. He retired and devolved his responsibilities Zen master to his Dharma heir Sochu Suzuki Roshi in 1973. A Zen master with a talent for Haiku (Japanese poems of seventeen syllables).

*

Soen Nakagawa (中川 宋淵; March 19, 1907—March 11, 1984) was a Rinzai Zen roshi and poet, the predecessor to two influential Zen teachers in the West, Maurine Stuart roshi and Eido Tai Shimano, the now retired abbot of the Zen Studies Society (now run by Shimano’s successor, Roko Sherry Chayat). Nakagawa was also an important figure in the formative years of several other American Zen teachers, including the late Robert Aitken roshi of the Honolulu Diamond Sangha and the independent Zen teacher, Philip Kapleau. He is remembered for his many eccentricities, such as the time he performed the Japanese tea ceremony with distinguished guests using Coca-Cola cans.

Nakagawa was a Dharma successor of Keigaku Katsube and served as head abbot of Ryutaku-ji. In his retirement he resided on the temple grounds where people would report hearing classical music drifting from his little hut during all hours of the day and night. Classical music was an art form which Soen loved dearly. Nakagawa’s Zen lineage continues today through Eido Shimano’s Dharma successors, including Roko Sherry Chayat and Genjo Marinello, Osho, and others like Jun Po Denis Kelly, founder of Mondo Zen. His is one of the only Western Rinzai Zen lineages that continues to be passed down over generations, on into modern-day.

In 2010 Nakagawa’s lineage found itself in turmoil following public allegations and disclosures on how Nakagawa roshi’s primary successor teaching here in the United States, Eido Tai Shimano, had misused his position of authority and had engaged in harmful sexual misconduct over the many years he was teaching. This caused many prominent Zen teachers within America’s Zen community to write letters to the board of directors of the Zen Studies Society, expressing their displeasure and calling for a complete removal of Shimano from any position of teaching authority at any of the Zen Studies Society training locations. Eventually, the board of directors did decide to separate itself from the former roshi and one of Shimano’s Dharma successors, Roko Sherry Chayat, took over as head abbot.

Biography

Soen Nakagawa was born Motoi Nakagawa on March 19, 1907 in Iwakuni, Japan. He was the eldest of three brothers and his father was a medical officer in the army. The Nakagawa family frequently moved in his childhood, with Soen having lived in both Iwakuni and Hiroshima. Nakagawa’s father died during his youth and his mother never remarried, so the family struggled to survive. Eventually Soen was admitted to Tokyo Imperial University, where he studied Japanese literature. He held a love and fascination for poetry, reading the works of Basho.Influenced by his love for Basho, Nakagawa was ordained an unsui in 1931 by Katsube Keigaku roshi of Kogaku-ji, a Rinzai Zen temple. Much of his time was spent in personal retreat on Daibosatsu Mountain, located in Yamanashi Prefecture. Soon, some of his poetry started getting published in a Japanese magazine called Fujin Koron (or, “Woman’s Review”), a publication which Nyogen Senzaki read. Impressed by Nakagawa’s poetry, in 1934 Senzaki initiated a correspondence with Nakagawa and these formed the foundations of a lifelong friendship shared between the two.

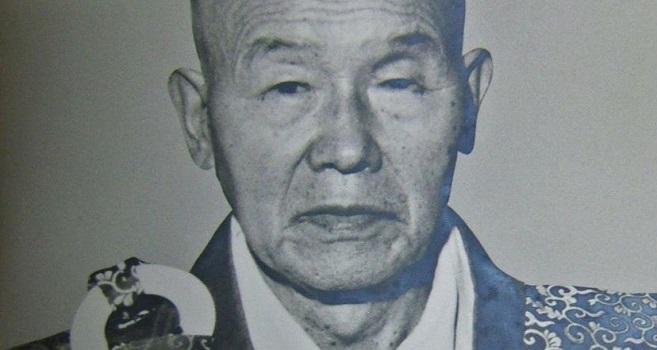

Nakagawa Sōen & Yamamoto GenpōIt was around this time that he met Ryutaku-ji’s abbot, Gempo Yamamoto. Soen continued having his poems published in other publications and soon after became a formal student of Gempo Yamamoto roshi. This was followed by an apparent two-year retreat spent on Daibosatsu Mountain, which was followed by his return to Ryutaku-ji to resume formal Zen studies. In 1950 he took over abbotship of Ryutaku-ji.

Nyogen Senzaki roshi, over the years of their friendship, would sometimes mention that Nakagawa should come to the United States and teach. Nakagawa had planned to make his first visit in 1941, a visit which never happened due to complications arising out of World War II.

So it was that it wasn’t until 1949 that Nakagawa made his first trip to the United States, greeted by Senzaki roshi, who arranged for him to give a talk at the Los Angeles Theosophical Society. In 1950 Soen Nakagawa returned to Ryutaku-ji in Japan and, not long after, a young Robert Aitken arrived there (upon the suggestion of Senzaki roshi) to begin studying under him. Philip Kapleau, the independent Zen teacher, arrived in the next year to also train with him. In all he made thirteen trips to the United States in his lifetime, leading intensive meditation retreats and spending time with students.

In 1960 Nakagawa roshi sent a young monk by the name of Eido Shimano to Hawaii to assist Robert Aitken in running the Honolulu Diamond Sangha. Soon after, Aitken reports that Shimano’s presence in the sangha broke the group off into factions. During this time, two of Aitken’s female sangha members were hospitalized and it was later documented by Aitken that these hospitalizations were allegedly the result of sexual encounters they’d had with Eido Shimano.

Dharma Successors

Nakagawa roshi given Dharma transmission to several individuals, one of which was done informally with Maurine Stuart roshi – an important woman who factors greatly into the advancement of women within the Western Zen mahasangha. Therefore, I’ve decided to include her name in the following list of Soen Nakagawa roshi’s Dharma successors: Eido Tai Shimano, Maurine Stuart, Suzuki Sochu, Fujimori Kozen of Hokko-ji, Immari Beijo and Nakagawa Dokyu.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Soen_Nakagawa

Nakagawa's Dharma Lineage

白隱慧鶴 Hakuin Ekaku (1686-1769)

峨山慈棹 Gasan Jitō (1727-1797)

卓洲胡僊 Takujū Kosen (1760-1833) aka 大道円鑑禅師 Daidō Enkan zenji

蘇山玄喬 Sosan Genkyō (1798-1868) aka 神機妙用禅師 Jinki Myōyō zenji

伽山全楞 Kasan Zenryō (1824-1893)

宗般玄芳 Sōhan Genhō (1848-1922)

玄峰宜雄 Genpō Giyū (山本 Yamamoto, 1865-1961)

宋淵玄珠 Sōen Genju (中川 Nakagawa, 1907-1984)

島野榮道 Shimano Eidō [Sotai] (1932-2018)

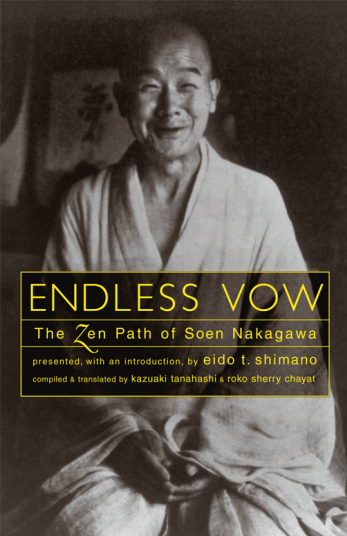

PDF: Endless Vow: The Zen Path of Soen Nakagawa

Ed. by Kazuaki Tanahashi & Roko Sherry Chayat

Boston: Shambhala Publications, Inc., 1996, 192 p.

Endless Vow is the first English-language collection of the literary works of Soen Nakagawa Roshi. An intimate, in-depth portrait of the master of Eido Tai Shimano, his Dharma heir, introduces the poems, letters, journal entries, and other writings of Soen Roshi, which are illustrated with his calligraphies. In a postscript, some of his best-known American students—including Peter Matthiessen and Ruth McCandless—reminisce about this legendary figure of American Buddhist history.

A Review by Lawrence Shainberg

https://tricycle.org/magazine/endless-vow-zen-path-soen-nakagawa/Soen Nakagawa Roshi (1907-1984) was a seminal figure in American Zen. For many American teachers and students, especially on the East Coast, it was his exemplary life and character that drew them into Zen practice and helped them persist when it proved to be so much slower and harder than anything promised by D. T. Suzuki. One of the first Zen masters who ventured—beginning in 1949—to these shores, Soen was abbot of Ryutaku-ji in Mishima, Japan, the New York Zendo in Manhattan, and Dai Bosatsu Zendo in Livingston Manor, New York. He was the dharma father of five well-known Zen masters, including the late Sochu Suzuki, who succeeded him at Ryutaku-ji; Kyudo Nakagawa (no relation), the present abbot of Ryutaku-ji, who founded the Soho Zendo in New York; and Eido Shimano, who founded Dai Bosatsu and the New York Zendo. Endless Vow , a remarkable and inspiring tribute to Soen, is a unique contribution to Zen literature. It includes a biography by Eido Roshi, several eloquent statements by former students, and a collection of Soen's poetry and journals, translated by Kazuaki Tanahashi, in which his energy and faith are so vivid and concrete that the typically accepted conflicts between Zen and language seem to fall away.

Soen had a classical education that left him with an enduring passion for both Eastern and Western cultures. Goethe, Dante, Beethoven, and Schopenhauer figured no less significantly in his teachings and poetry than Bassho and the great Zen patriarchs. Ordained as a monk at the age of twenty-four, Soen displayed from the start an individuality and eccentricity that did not endear him to the Zen establishment. Zen, he said, was “fundamentally about the emancipation of all beings [but] unfortunately sealed in some square box called Zen.” At Ryutaku-ji, where he had gone to study with his teacher, Gempo Yamamoto Roshi, his dietary habits (at the time he ate no cooked food), his inclinations toward travel and solitary retreat, and his tendency to ignore the official monastery schedule and sit all day and all night led his fellow monks to complain to Gempo, suggesting he might be better off at another monastery. The same habits continued after Gempo, to the amazement of Soen as well as almost everyone else, made Soen his successor in 1951. Unlike other abbots, Soen insisted on taking his meals and sitting zazen with his monks, and he raised eyebrows among those who believed an abbot had “finished” his training by attending sesshin with Harada Sogaku Roshi at Hosshin-ji. No doubt it was the same independent spirit that led to his friendship with Nyogen Senzaki, the itinerant Zen monk who was the first resident teacher in the United States, and, later, on his many visits to this country, to his deep connection with American students, whom he found “more sincere” than the Japanese.

In 1967, Soen suffered a near-fatal accident that left him with a piece of bamboo imbedded in his skull. Surgeons wanted to operate, but he refused. For the rest of his life, the excruciating pain he suffered as a result of this wound led to long periods of solitary retreat and increasing bouts of what Eido Roshi calls “unpredictable, erratic behavior.” “Practitioners in America,” he writes, “loved his spontaneity and viewed his actions as indications of his ‘crazy wisdom,' but in Japan, people were not so understanding… It was clear to those of us who knew him well that he was suffering from depression during the last few years of his life, but his need for privacy, his shyness, and his pride wouldn't allow him to admit it.”

Many of those who knew Soen, especially those like me who attended the New York Zendo during the period of Soen's “depression,” will find such a description reductive and disrespectful. Like everyone else connected to the community, Soen was aware that allegations of sexual misconduct had been directed at Eido, so it is hardly unreasonable to assume that his “erratic behavior” was less a matter of internal psychology than the pain and embarrassment he felt about the behavior of his principal disciple in America. Eido's reference to this period without any mention of his own role at the time seems disingenuous to me.

Still, such caveat seems trivial beside the portrait of Soen that emerges from his poetry and journals. At the age of twenty-seven, after a long fast in solitary retreat, Soen wrote the following pair of haiku a few weeks apart:

Flesh withering

Among myriad petals

I stand aloneTears of gratitude

biting into a cucumber—

dharma flavorThe three conditions here described—aloneness, gratitude, and faith in the dharma—are Soen's constant refrain. Like all great haiku, however, his are less description than embodiment of their subjects. And since his subject is always dharma, one cannot help but feel that these haiku are not about the dharma, but dharma itself. Present in these pages is a man for whom life itself was dharma, a constant reaffirmation of the vow that gives the book its title. “To my knowledge,” writes Eido, “no other roshi in Japan had Soen Roshi's courage, faith, and enthusiasm for the dharma.”

“Why did you become a monk?” Eido asked him once.

Soen replied, “I so badly wanted to become a monk.”

“But why?”

“I so badly wanted to become a monk.”

It is worth noting that the mind from which these words sprang was not unsophisticated. Dualism and self-consciousness, not to mention the capacity to explain a matter so important as one's choice of monasticism, were hardly unknown to it. This is a book about a monk who transcended such explanation, a man, finally, who took the dharma seriously. Think of it as medication, the perfect antidote to weakening of faith.

Chronology, pp. 159-161.

1907

Born March 19 in Keelung, Formosa (now Taiwan), to an

army physician, Dr. Suketaro Nakagawa, and his wife, Kazuko,

and given the name Motoi.

Family moves to Iwakune and then to Hiroshima.1917

Father dies.

1923

Enters First Academy in Tokyo.

1927

Enters Tokyo Imperial University; lives in dormitory at Gangyo-

ji, a Pure Land temple.1931

Completes graduate school at Tokyo Imperial University.

Ordained March 19 by Keigaku Katsube Roshi at Kogaku-ji.

Begins solitary retreats on Mount Dai Bosatsu.

Becomes a student of haiku master Dakotsu Iida.1932

Conceives of International Dai Bosatsu Zendo and travels to

Sakhalin Island to search for gold in order to fund the

project.

Shubin Tanahashi becomes a student of Nyogen Senzaki.

Eido Tai Shimano is born in Nakano, Arai, a district of

Tokyo.1933

Completes Shigan (Coffin of Poems).

1934

Poems and essays from Shigan (Coffin of Poems) printed in

Fujin Koron.1935

Hears Gempo Yamamoto Roshi's teisho at Hakusan Dojo;

later has private meeting with him and is invited to be his

student at Ryutaku-ji and in Manchuria.

Correspondence with Nyogen Senzaki begins.1937

First trip to Manchuria with Gempo Roshi.

1939

Solitary retreat on Mount Dai Bosatsu.

1941

Ryutaku-ji is officially acknowledged as a monastic trainin

center. War in the Pacific starts.1945

War in the Pacific ends.

1949

First of thirteen trips to the United States. Publishes Meihen

(Life Anthology).1951

Installed as abbot of Ryutaku-ji.

1954

Meets a young monk, Tai Shimano, at funeral service for Daikyu

Mineo Roshi; that summer, the monk becomes his student

at Ryutaku-ji,1955

Second visit to the United States.

That September, Nyogen Senzaki returns to Japan for the

first time since his departure in 1905; visits Ryutaku-ji during

his six-week stay.1957

Death of Soen Roshi's ordination teacher, Keigaku Katsube

Roshi.1958

Death of Nyogen Senzaki; third trip to the United States, to

settle Senzaki's affairs, having been named the executor of his

estate.1959

Fourth trip to the United States.

1960

Fifth trip to the United States; flies to Honolulu, Hawaii, to

lead first sesshin there.

Eido Tai Shimano's arrival in the United States.1961

Death of Gempo Yamamoto Roshi.

1962

Mother dies.

1963

Travels around the world with Charles Gooding, one of Nyogen

Senzaki's students. Visits the United States, India, Israel,

Egypt, England, Austria, and Denmark, flying over the Arctic

Circle on his way back to Japan.

Underground plumbing system installed at Ryutaku-ji.1966

Engages in fundraising to acquire land surrounding Ryutakuji.

1967

Near-fatal accident.

1968

Seventh visit to the United States; with him in the ship's hold

is the Amitabha Buddha image from main altar at Ryutaku-

ji, to be installed on the main altar of New York Zendo

Shobo-ji, which opens September 15.1969

Travels to sesshin at sanghas in Israel, England, Egypt, and

the United States (New York, California, and Hawaii).1971

Ninth visit to the United States.

Zen Studies Society purchases fourteen hundred acres in the

Catskill Mountains for International Dai Bosatsu Zendo.1972

Tenth visit to the United States.

1973

Retires from abbotship of Ryutaku-ji.

Publication of "Ten Haiku of My Choice."1974

Eleventh visit to the United States, to stay at International

Dai Bosatsu Zendo with Father Nyokyu Maxima, who paints

a mural there.1975

Twelfth visit to the United States; gives first teisho in new

monastery building; that fall, goes into solitary retreat at New

York Zendo Shobo-ji,1976

Official opening of International Dai Bosatsu Zendo.

One-hundredth anniversary of Nyogen Senzaki's birth.1981

Publishes Henkairoku (Journal of a Wide World) with Kounsho

(Ancient Cloud Selection).1982

Last visit to the United States.

1984

March 11,departure.

Nakagawa's Dharma Lineage

白隱慧鶴 Hakuin Ekaku (1686-1769)

峨山慈棹 Gasan Jitō (1727-1797)

卓洲胡僊 Takujū Kosen (1760-1833)

蘇山玄喬 Sosan Genkyō (1798-1868)

伽山全楞 Kasan Zenryō (1824-1893)

宗般玄芳 Sōhan Genhō (1848-1922)

玄峰宜雄 Gempō Giyū (1866-1961)

中川宋淵 Nakagawa Sō'en (1907-1984)

Dharma Heirs:

鈴木宗忠 Suzuki Sōchū (1921-1990), abbot of Ryūtaku-ji: 1984-1990

中川球童 Nakagawa Kyūdō (1927-2007), abbot of Ryūtaku-ji: 1990-2007

藤森弘禅 Fujimori Kōzen (1925-1984)

嶋野 (タイ) 栄道 Shimano (Tai) Eidō (1932-2018)

In the front row Suzuki Sōchū, Yamamoto Genpō, Nakagawa Sōen

Remembering Nakagawa Soen Roshi

http://www.soennakagawaroshi.com/

Original book compiled and published by Estelle Kashin Gerard, 2008.

Internet version by Kobutsu Malone-osho and Adam Genkaku Fisher, 2012.

Readers can page through the book at the website. The book, originally intended as a gift to Ryutakuji in Japan, offers glimpses in to who Soen Nakagawa Roshi was with poems and articles by those who knew him.

The Soen Roku: The Sayings and Doings of Master Soen

Zen Studies Society Press, 1986, 198 p.

Teisho: Day One

"This is the first teisho of the sesshin. Everything is scheduled, not only human beings. Everything, indeed. Mountain, running river, sound of wind, singing of birds — everything. Especially children, who are wonderful Zen teachers, of course.

Everything is our teacher. This! (Bang!) This is the real one point; very easy to understand. Too clear, too easy to get This! (Bang!) Everything is giving a teisho.

Please, don't miss this (Bang!), this most important point, okay? There are many sutras and shastras. Many, many teachings, not only about Buddhism and Christianity. There are many, many books. But when we meet (Bang!) this one point, all sutras and shastras and all philosophical and spiritual words become a mistake. Only one point. (Bang! Bang! Bang!) Only one. This is the true teaching of Bodhidharma, all patriarchs, Buddha Shakyamuni. This! Okay?

Each of you is a wonderful bodhisattva. I'm not saying this in praise, or for encouragement. Truly, you are living bodhisattvas. Living Dai Bosa. There is a wonderful Buddha statue at the Metropolitan Museum. There are national-treasure bodhisattvas and many statues. They are wonderful, of course. I pay them gachimi, gachimi. But, you are living bodhisattvas, each of you, living! Not bronze, or wood. Sometime, something bad may happen. If something goes wrong, “Oh, I will pray to Buddha.” No, no, no! There is no such Buddha. Realize this! (Bang!) and every human becomes wonderful.

So in the Bodhisattva's Vow, “Extend tender care even to such beings as birds and beasts.” Not only beasts, not only birds. But to insects too, okay? Even one flower, one speck of dust. There is a Zen saying, “When I pick up one speck of dust, all nations are united.”

Teisho is not always a talk about some great Zen master, or Buddha Shakyamuni's sutras, or Rinzai's lectures. Rinzai himself says, “Don't take my teisho” — don't hold to my teisho. OPEN YOUR OWN EYES! Everything is a living sutra. Every day you are (Bang!). Each deed is a living sutra. Picking up a cup, drinking water — nothing else. As the Bodhisattva's Vow says, “In any event, in any place, and in any moment” — now! — none can be other than This! This! THIS! There is no need for Buddha's teaching, or some brilliant exposition. This is best.

So, after Purification, we recited together, “Opening This Dharma. This Dharma, incomparably profound and minutely subtle, is hardly met with, even in hundreds of thousands of millions of eons.” Hardly met with. During hundreds of thousands of millions of eons, we are always meeting with This! “Meet” is one “This,” and one “meet,” not thousands. Nothing else but This, okay? Nothing else but This. ANSWER!

(Students: Hai!)

OKAY?

(Students: Hai!)

Wonderful! Congratulations. This is true teisho. Only This.

In Dr. Daitsu Suzuki's translation, “Opening ‘The' Dharma. ‘The' Dharma, incomparably profound and minutely subtle, is hardly met with, even in hundreds of thousands of millions of eons. Now we can see ‘it,' listen to ‘it,' accept and hold ‘it.'” It, it, it. NO! So it takes us over thirty years to correct wonderful Dr. Daitsu Suzuki's translation. Not “it.” But “this.” Now we can SEE! I can see your face. I cannot see my own face, of course. Now we can see (Bang!). Now. Now we can see This. Listen to This — all the birds are chirping; not only you can get This. Indeed, I'm not telling a lie. Everything is wonderful! So, we get these miserable, cruel karma relations changed into wonderful dharma relations, with (Bang!). Please, (Bang!) nothing else but This. I'm explaining, talking too much. Excuse me.

“Now we can see This, listen to This, accept and hold This. May we truly understand….” There are many kinds of understanding: I understand you; I understand everything. But true insight, true understanding is with This. Not only understanding. True understanding becomes true realization, and true actualization. This is our training, not just our vow. We should actualize EVERY DAY, okay? Every Day. Every day. Nothing else but This, is our training.

This is the true teaching of Buddha Shakyamuni and all the patriarchs. And this morning's teisho is a true teisho, true Buddha Dharma. There are many Zen centers and many Zen temples, Zen churches. But truly to get This is very difficult. I'm congratulating myself. Without your wonderful bodhisattva's response, I cannot talk like this. In my own room, I cannot talk like this. You are talking my talk. You are giving teisho. Thank you very much; thank you.

With this mind, everyday life becomes “every day is a good day.” You know this saying. Even in fear, we can say, EVERY DAY IS A GOOD DAY. Even a miserable day. Even a cruel day. We must become every-day-is-sun-shining day. With This! This is the point. This is the wonderful key to open many things. Probably after my teisho, you will forget my This, of course. So, reciting Namu Dai Bosa, Namu Dai Bosa… is a very good help. Not only to you, to me too. I'm always losing This, forgetting This, and committing mistake after mistake. But mistakes and failures are very good lessons for us. Don't become sorry, “Oh, again I committed such a miserable mistake.” Okay! With this one experience, we become more, more, more — “this mind.” Every day is a wonderful training place. Training is not always joyful training, but every day becomes more and more joyful, more and more full of gratitude, and more, more, more, endless long wonderful…. So, Namu Dai Bosa.

There's no need for reciting Namu Dai Bosa of course, but Namu Dai Bosa is very effective. As you know, “bosa” means bodhisattva. Bodhisattva's Vow. Probably you have memorized it already. “Okay,” you say. “I understood the Bodhisattva's Vow.” But each time I recite this Vow, or the Heart Sutra, each time, some part of it really touches me.

“Bodhi” and “sattva.” “Bodhi” means so-called enlightenment. But don't think, “Oh, I am not yet enlightened. Some day I'll get enlightenment.” From today, forget such! From the beginning, we are the Enlightened One. Believe this with definite faith. This is not only the Song of Zazen, “From the beginning, all sentient beings are Buddha….” You are not merely chanting. It means, from the beginning, you are the Enlightened One! Realize this. Realize this. And have definite faith in this. Not only the Song of Zazen, but also the Heart Sutra is saying so. “Bodhi” means “enlightenment” — “some day, I will get enlightenment,” no! There's no need for more enlightenment; already we are full.

Some Zen master said, “When I hear the sound of Buddha, I want to close my ears.” There's no need for the name of Buddha, or Zen, or such-and-such. After we realize This, and have understood This, there's no need to hear more. We chant sutras, we practice zazen together with mindfulness. We should be mindful.

Please recite from the Meal Sutra: “Thirdly, what is most essential is the practice of mindfulness, which helps us….” All together please, “Thirdly…”

(Students: “Thirdly, what is most essential is the practice of mindfulness, which helps us transcend greed, anger, and delusion.”)

What is the English word? “Neurotic?” Neurotic mindfulness is no good. It must be with This. This is the teaching of the Tea Ceremony, and Flower Arranging. Tea master Rikkyu said, “The Way of Tea is nothing else but boiling cold water and making tea.” Make tea and drink it. Nothing else. To become mindful is wonderful training. It is very good to become mindful. But Rikkyu said, the Way of Tea is nothing else but, with hot water, making tea and drinking it. Nothing else but this. So Rikkyu is giving us a teisho about This. Nothing else!

What is Buddha? What is Buddha? “Shit-wiping stick,” Ummon said. “Shit-wiping” — the ancient Chinese didn't have paper; paper was very difficult to get. So they always brought a shit-wiping stick. It is as important as your spoon and knife. (Laughter.)

So, Ummon, our great patriarch. When I think of Ummon, Cloud Gate Zen master, my tears are many. What is Buddha? Ummon answered, “Shit-wiping stick.” So, for us, “What is Buddha? One piece of toilet paper.” One piece of toilet paper. One drop of tea. One drop of coffee. Nothing else but that. Realize this. There's no need always to be thinking, “Oh, this is wonderful, this is Buddha.” No need.

Some of you are nurses — wonderful. You are living Kanzeon Bosatsu. I am only a lazy, mountain monk. But please, with this mind, take care of your many patients. Nursing is wonderful training.

I do not like to say “Zen,” but as I need the name, so I am talking Zen, Zen, Zen…. Everyone — not only nurses — each of you is a wonderful bodhisattva. So, I am bowing, of course to the Buddha, bowing to you all. So with this mind, please, let us bow to each other. Wife and husband — please, I am not joking, okay? — bow with This Mind. Not only to Buddha, but to each other. To the living bodhisattva that is each of you. So, bow together, looking at me. So, without exception each of you is a living Buddha, Dai Bosatsu. Without exception, okay?So, each one is best. Not only human beings, each is best. Nothing else. Each one is BEST! This is the teaching of Buddha Shakyamuni.

In the sutra about Buddha's birth, where he takes seven steps in each direction — this is not true of course; he cries the same cry we all do when we come out of our mother's sacred womb. What does that saying mean? “Under the heaven, on the Earth, tenjo tenga uiga dokusan?” The literal translation is, “I am the best one.” No, this is wrong. Not myself only, but each one is best. Wonderful. This is not a conscious thought. Truly this is so. Tenjo tenga uiga dokusan. Each one is best.

Almost all Zen students begin with the Mumonkan's first koan, “Mu.” The serious student did not visit Joshu to talk to him about a dog, or a Buddha-dog, or whether a dog has Buddha Nature. In front of such a wonderful, great Zen master, Joshu, the sincere, honest student really asked, “What is true enlightenment? Please show me and let me see true enlightenment. Enlighten!” To this, Joshu only responded, “Mu.” This “one piece of toilet paper.” This “mu.” Nothing else but this. Mu-uu-uu-u! So, in Zen training, Mu is not just the first koan. All is Mu. Mu, mu, mu, mu. Namu dai bosa and mu are the same; nothing else but. But to continue practice with “one piece of toilet paper, one piece of toilet paper” is probably very difficult. Namu dai bosa, or Mu, is very good!

So, we have been thinking about birth. When your mother was giving birth, she was not speculating, What is birth? She was not thinking, Is it a boy or a girl? She was just making the birth-sound.

But some time, some day, we all leave this wonderful world. Some day. But looking at your faces, I see no “Some day I'll leave this wonderful world; I must die.” There is a senryu, a short, witty verse: “When I look at your face, all faces, show ‘now I will live forever.'” I thought this was a sarcastic comment. But D.T. Suzuki told me, “This is a wonderful senryu — it is not sarcastic at all. We live forever! No need for “some day I will die.” Do you understand? That's what Dr. Suzuki said to me. But truly (Knock! Knock!) our life is forever!

So, when some day we will say goodbye, let us not cry. Some crying is okay, but don't make others cry. My wonderful teacher, Gempo Roshi, was smiling. Many Zen masters know one week before. They know the day. My last day, I promise Eido Roshi, with smiling, okay? When it is our last breath, it is our last breath. “Is that so, doctor?” That is our last Mu. When we're born, there is our mother's birth-sound. And when we leave, this Mu.

I have many, many matters I want eagerly to talk to you about.

In the translation of the Bodhisattva's Vow there is, “…even to such beings as beasts and birds.” Not only beasts and birds, not only insects… each, each, each. “This realization teaches us that our daily food and drink, clothes, and protections of life, are the flesh and blood, the merciful incarnation of Buddha….” This “incarnation” is no good. There is bad understanding about this true fact. Someone says, “Ah, when I die, everything will vanish away.” No, no. Someone thinks, “Though my body disappears, my mind, some soul, will be unchanging.” Too easy! Bad understanding. Buddha Shakyamuni says, everything is Buddha. “Transformation” is a better word that “incarnation.” Every wonderful being is warm flesh and blood. As in the Christian Mass, one piece of bread is Christ. So, after mass, we and the Father become one, by means of the piece of bread. This is (Knock, Knock, Knock) one piece of bread. Exactly the same. “The warm flesh and blood, the merciful ‘transformation'”… everything will change. Not only us — not only us! The sun is transforming. This is Buddha's important teaching. Buddha, of course, changed. Everything — there is nothing else but changing, transforming. So, “transformingly.” But I might say, “transformation-ing,” okay? Everything is transformation-ing!"

From The Soen Roku: The Sayings and Doings of Master Soen, copyright 1986 by The Zen Studies Society Press

PDF: Zen Radicals, Rebels and Reformers

by Perle Besserman and Manfred Steger

Boston: Shambhala Publications, Inc., 1991;

Wisdom Publications, Boston, 2010.

Chapter 8. Soen: The Master of Play, pp. 159-175.

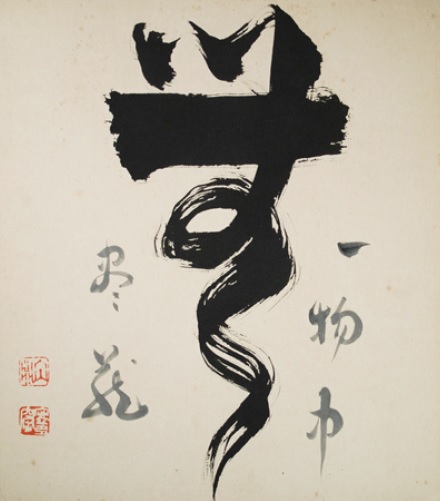

"Within not-a-thing lies infinite treasure!"

Calligraphy by Nakagawa Sōen