ZEN IRODALOM ZEN LITERATURE

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

船子德誠 Chuanzi Decheng (820-858)

[華亭船子德诚 Huating Chuanzi Decheng]

(Rōmaji:) Sensu Tokujō

(Korean:) 선자덕성 Seonja Deokseong

(English:) ”The Boatman Monk”

(Magyar:) Csuan-ce Tö-cseng, a révész szerzetes

Tartalom |

Contents |

Csuan-ce Tö-cseng, a révész szerzetes verse A csónakos szerzetes |

Chuanzi Decheng Ch'an Master Teh Ch'eng The Boat Monk at Hua Ting The Boat Monk |

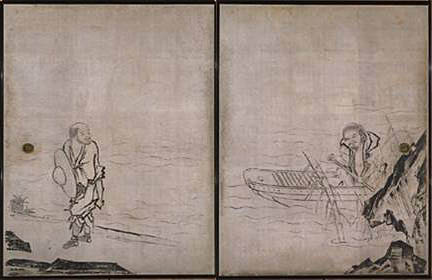

【禅宗公案】 华亭船子德诚禅师与夹山图, 32.37 x 12.87 cm,

painted by 狩野如川周信绘 Kanō Josen Chikanobu (1660-1728),

eldest son of Tsunenobu of the Kobiki-chō branch of the Kanō school,

succeeded his father as third head of the school in 1713,

and in 1719 was awarded the highest court title, hōgen ('Eye of the Law').

The Boat Monk is 華亭德誠 Huating Decheng, a student of the Caodong master 藥山惟儼 Yaoshan Weiyan (745–828). Decheng resided on a boat, ferrying people across the river and teaching them Chan. One day a young monk named Shanhui (805–881) came to seek out this monk for instructions. After some exchange of words, Decheng realized the potential of Shanhui, so he posed a question to him. When Shanhui tried to answer, Decheng knocked him off the bot into the river and retorted, ”Speak, speak!” At this point the young monk became enlightened. Decheng pulled him up and said,“Today I have finally caught a big golden fish!” The two stayed all night on the river, sometimes talking, sometimes silent. In the morning Decheng bade farewell to Shanhui and left him on the shore. He said to him,“I studied under Yangshan for thirty years. Today I have repaid his kindness. From now on, you need not think of me again.”Then he rowed the boat to the middle of the river and tipped it over and disappeared “without a trace.” Shanhui later became a Chan master at Mount Jia.

Cf. Five Lamps Meeting at the Source. See T.no.1565, 80: 115a.

Attaining the Way: A Guide to the Practice of Chan Buddhism

By Sheng Yen (Shambhala, 2006)

Jiashan Shanhui [Kassan Zen`e] 夾山善會 (805–881) was born in Xianting 峴亭 in Guangzhou 廣州; his surname was Liao 廖. While still a child he became a monk on Mount Longya 龍牙, in modern Hunan. Later he went to Jiangling 江陵 in modern Hubei, took the precepts, and became a lecture master 座主. One night when Shanhui was lecturing in Jingkou 京口, where he had subsequently gone to live, a monk asked, “What is the dharmakāya?” Shanhui answered, “The dharmakāya is without form.” “What is the dharma eye?” the monk then asked. Shanhui said, “The dharma eye is flawless. Before the eyes there are no dharmas. Though the meaning exists before the eyes, it cannot be reached by the eyes or ears.” At this point the visiting monk laughed. When Shanhui asked why he had laughed, the monk, Daowu Yuanzhi 道吾圓智 (769–835), suggested that he go to Huating 華亭 to see Chuanzi Decheng 船子德誠 (n.d.), a monk who was at that time working as a ferr yman. Decheng, Daowu said, “hasn't a tile to cover his head above, nor a gimlet point of earth to stand on below.” Shanhui went straightaway to Huating and found Decheng in his boat on the river. In the subsequent encounter Shanhui thoroughly penetrated Decheng's dharma. Decheng told him to avoid crowded cities, live in the mountains, and concentrate on finding a successor to keep the dharma alive. He then tipped over his boat and was never seen again. Shanhui lived in seclusion for over thirty years. In 870 he and the assembly that had gathered around him built a monastery, Lingquan yuan 靈泉 院, on Mount Jia 夾山.

Note in The Record of Linji

by Ruth Fuller Sasaki

Sensu Kassan 船子・夾山

Ch: Chuanzi Jiashan. A painting subject of the meeting between the Chinese Zen 禅 priests Chuanzi (Jp: Sensu 船子) and Jiashan (Jp: Kassan 夾山) during the 9c. Chuanzi, after leaving monastic life, took a job ferrying a small boat across the river at Songjiang 松江, present day Shanghai 上海. While on his boat, Chuanzi was fond of instructing his passengers about finding self-realization, lifting an oar and asking "Do you understand?" He thus gained the nickname the priest Ferryman (Ch: Chuanzi Heshang; Jp: Sensu Oshou 船子和尚). One day the priest Jiashan (805-880) came on board the boat and Chuanzi engaged him in a dialogue. According to one version, Chuanzi threw Jiashan into the water, then hit him three times with his paddle, whereupon Jiashan reached enlightenment. In any case, Chuanzi, realizing that in Jiashan he had found a worthy successor, jumped into the river and sank. Typically paintings show Jiashan on the boat and Chuanzi in the water. Among Japanese painting on the subject, Hasegawa Touhaku's 長谷川等伯 (1539-1610) screen painting Zenshuu soshi-zu 禅宗祖師図 in Nanzenji Tenjuan 南禅寺天授庵, Kyoto, is well known.

船子夾山図 Sensu Kassan zu

「船子夾山図」

by 長谷川等伯 Hasegawa Tōhaku (1539-1610)

Chia-shan and the Ferryman

by 松花堂昭乗 Shōkadō Shōjō (1584-1639)

Calligraphy by Tenyu (1586-1666)

28.6 x 54 cm

Philadelphia Museum of Art

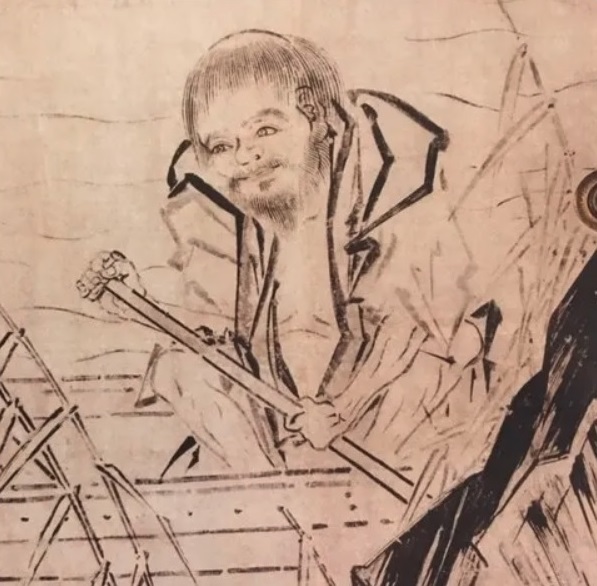

“Chuanzi and Jiashan”

by

海北友松 Kaihō Yūshō (1533-1615)

Hanging scroll, ink on paper

108.0 x 50.8 cm.

Artist's seal: Yūshō

Colophon: by Gyokushitsu Sōhaku (1572-1641), a Daitokuji monk

Kaihō Yūshō was the fifth (or third) son of Kaihō Tsunachika (1510-1573), a retainer of Azai Nagamasa (1545-73), an influential daimy ō during the Momoyama period. A native of Ōmi (present-day Shiga prefecture), Yūshō is also identified by the names Yūtoku and Jōeki. When Oda Nobunaga attacked the Azai clan in 1573, the Kaihō family was also destroyed. managed to survive this incident because he had been living as a Zen monk at the Tōfuku-ji temple in Kyoto since his early years.

Yūshō studied painting in the Kano School and is said to have received guidance from Kano Motonobu (1476-1559) and Kano Eitoku (1543-1590), being especially taken with the ink monochrome style of the Chinese painter Liang Kai (late 12th-13th century). His talent was highly appreciated by Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537-98), for whom he worked at Juraku-dai. The vigorous expression apparent in one of the earlier works by Yūshō, the "Dragons in Clouds" painted for Ken'nin-ji in 1599, indicates his strong desire to be a samurai. Although Yūshō laicized himself at age 41, and attempted to restore the Kaihō family as a warrior clan, his ambition was never fulfilled while, on the other hand, he became increasingly famous for his paintings.

Yūshō had a close relationship with Prince Toshihito (1579-1629) and with the daimyō Kamei Korenori (1557-1612). Around 1602 he was patronized by Emperor Goyōzei (1571-1617) and began to produce more colorful works inspired by the yamato-e tradition. Nevertheless, in his latest years his works were characterized by monochrome ink paintings with simplified brush strokes portraying figures like inflated bags, the so-called fukuro jinbutsu, as we seen in the present painting. These characteristics were particularly favored by Zen monks and Imperial connoisseurs, and the present work bears an inscription by the eminent Daitokuji monk Sō haku. The tradition founded by Yūshō, called the Kaihō School, prospered until the end of the Tokugawa era.

“Chuanzi and Jiashan”

by 梵因陀羅 Fanyin Tuoluo, a.k.a. Yintuoluo (14th century)

Hanging scroll, ink on paper, 57.4 x 29.1 cm.

A figure in monk's robe, holding an oar, stands at the prow of a covered boat, looking down at another figure on the shore who holds up his hands and bows low in obeisance. Quickly-brushed reeds complete the picture, the range of their tonality creating some degree of spatial recession in the work. While the brushwork is abbreviated and simplified, in combination with the ink washes the result is quite convincing of solid figures existing within a three-dimensional environment.

Ch'uan-tzu Ho-shang, the "Ferryman Priest," was a monk named Te-ch'eng who came from Sui-ning in Szechuan province. After becoming a disciple of the eminent prelate Yao-shan Wei-yen, Te-ch'eng moved to Hua-t'ing, where he acquired a small boat and daily ferried travellers across the river, conversing with them as he worked. One day his passenger was Chia-shan Shan-hui, who apparently was the first to truly respond to the Ferryman's teachings. On leaving the boat to continue on his way, Chia-shan turned to look several times at his new master, who thereupon overturned his boat and drowned, effectively preluding any further discourse between the two. The subject had appeared during the Yuan period in China (Fan-yin T'o-lo: "Ch'uan-tzu and Chia-shan"), and both paintings show the protagonists at the penultimate moment, just before Ch'uan-tzu acts so as to prevent Chia-shan from questioning his new understanding.

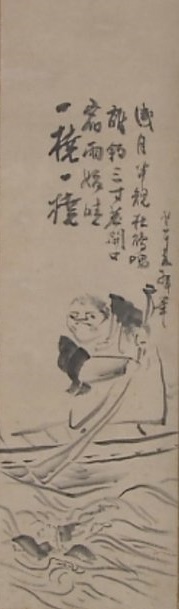

船子夾山自画賛 「離鉤三寸 何不言一句」

by 白隠慧鶴 Hakuin Ekaku

(1686-1769)

Sensu Kassan with self-inscriprion

114×51cm

「船子夾山図」 Sensu Kassan

by 仙厓義梵 Sengai Gibon (1750-1837)

「船子夾山図」 Sensu Kassan

by 長沢芦雪 Nagasawa Rosetsu (1754–1799)

船子夾山図 Sensu Kassan

by 風外本高 Fūgai Honkō (1779-1847)

名古屋市博物館蔵

CHUANZI DECHENG

by Andy Ferguson

In: Zen's Chinese Heritage: The Masters and Their Teachings, Wisdom Publications, pp. 163-166.

CHUANZI DECHENG (805–881 [sic!]), also known as the “Boatman” or “Boat Monk,” was a disciple and Dharma heir of Yaoshan. His lay home was located in Suining (now a place in modern Sichuan Province). Decheng studied with Yaoshan for thirty years and received the mind seal. Later, he lived in relative seclusion at Huating, on the bank of the Wu River (in the area of modern Shanghai), where he used a small boat to ferry people across the river.

Zen master Chengzi Decheng of Huating in Xiuzhou possessed great integrity and unusual ability. At the time when he received Dharma transmission from Yaoshan he intimately practiced the Way with Daowu and Yunyan. When he left Mt. Yao he said to them, “You two must each go into the world your separate ways and uphold the essence of our teacher’s path. My own nature is undisciplined. I delight in nature and in doing as I please. I’m not fit [to be head of a monastery]. But remember where I reside. And if you come upon persons of great ability, send one of them to me. Let me teach him and I’ll pass on to him everything I’ve learned in life. In this way I can repay the kindness of our late teacher.”Then Decheng departed and went to Huating in Xiuzhou. There he lived his life rowing a small boat, transporting travelers across the river. People there didn’t know that he possessed farreaching knowledge and ability. They called him the “Boat Monk.”

Once at the boat landing at the side of the river an official asked him, “What do you do each day?”

Decheng held the boat oar straight up in the air and said, “Do you understand?”

The official said, “I don’t understand.”

Decheng said, “If you only row in the clear waves, it’s hard to find the golden fish.”

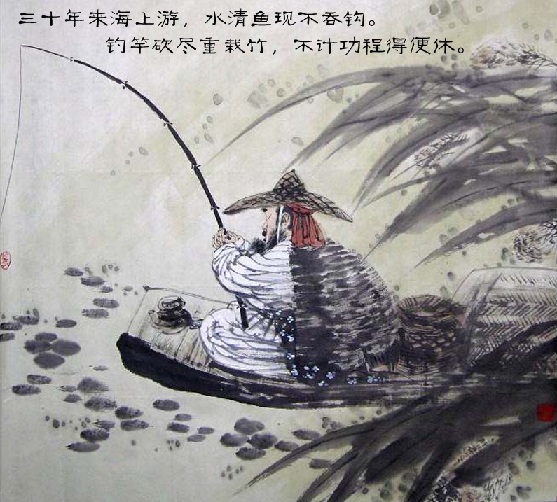

Decheng composed a verse that said:

Thirty years on the river bank,

Angling for the great function,

If you don’t catch the golden fish, it’s all in vain.

You may as well reel in and go back home.Letting down the line ten thousand feet,

A breaking wave makes ten thousand ripples.

At night in still water, the cold fish won’t bite.

An empty boat filled with moonlight returns.Sailing the sea for thirty years,

The fish seen in clear water won’t take the hook.

Breaking the fishing pole, growing bamboo,

Abandoning all schemes, one finds repose.There’s a great fish that can’t be measured.

It embraces the astonishing and wondrous!

In wind and thunder transformed,

How can it be caught?Others only seek gathering lotus flowers,

Their scent pervading the wind.

But as long as there are two shores and a lone red boat,

There’s no escape from pollution, nor any attainment of emptiness.If you asked, “Is this lone boat all there is in life?”

I’d say, “Descendants will each see the results.”

Not depending on earth or heaven,

When the rain shawl is removed, nothing’s left to pass on.

[Later,] Daowu went to Jingkou where he happened to see Jiashan Shanhui give a lecture. A monk attending the talk asked Jiashan, “What is the dharmakaya?”

Jiashan said, “The dharmakaya is formless.”

The monk asked, “What is the Dharma eye?”

Jiashan said, “The Dharma eye is without defect.”

When he heard this, Daowu laughed loudly in spite of himself.

Jiashan got down off the lecture platform and said to Daowu, “Something I said in my answer to that monk was not correct and it caused you to laugh out loud. Please don’t withhold your compassionate instruction about this!”

Daowu said, “You have gone into the world to teach, but have you not had a teacher?”

Jiashan said, “I’ve had none. May I ask you to clarify these matters?”

Daowu said, “I can’t speak of it. I invite you to go see the Boat Monk at Huating.”

Jiashan said, “Who is he?”

Daowu said, “Above him there’s not a single roof tile, below him there’s no ground to plant a hoe. If you want to see him you must change into your traveling clothes.”

After the meeting was over, Jiashan packed his bag and set out for Huating.

When Decheng saw Jiashan coming he said, “Your Reverence! In what temple do you reside?”

Jiashan said, “I don’t abide in a temple. Where I abide is not like…”

Decheng said, “It’s not like? It’s not like what?”

Jiashan said, “It’s not like the Dharma that meets the eye.”

Decheng said, “Where did you learn this teaching?”

Jiashan said, “Not in a place which the ears or eyes can perceive.”

Decheng said, “A single phrase and you fall into the path of principle. Then you’re like a donkey tethered to a post for countless eons.”

Then Decheng said, “You’ve let down a thousand-foot line. You’re fishing very deep, but your hook is still shy by three inches. Why don’t you say something?”

As Jiashan was about to speak Decheng knocked him into the water with the oar. When Jiashan clambered back into the boat Decheng yelled at him, “Speak! Speak!”

Jiashan tried to speak but before he could do so Decheng struck him again. Suddenly Jiashan attained great enlightenment. He then nodded his head three times.

Then Chuanzi said, “Now you’re the one with the pole and line. Just act by your own nature and don’t defile the clear waves.”

Jiashan asked, “What do you mean by ‘throw off the line and cast down the pole’?”

Chuanzi said, “The fishing line hangs in the green water, drifting without intention.”

Jiashan said, “There is no path whereby words may gain entry to the essence. The tongue speaks, but cannot speak it.”

Chuanzi said, “When the hook disappears into the river waves, then the golden fish is encountered.”

Jiashan then covered his ears.

Chuanzi said, “That’s it! That’s it!” He then enjoined Jiashan, saying, “Hereafter, conceal yourself in a place without any trace. If the place has any sign don’t stay there. I stayed with Yaoshan for thirty years and what I learned there I’ve passed to you today. Now that you have it, stay away from crowded cities. Instead, plant your hoe deep in the mountains. Find one person or one-half a person who won’t let it die.”

Jiashan then bid Chuanzi goodbye. As he walked away he looked back at Chuanzi.

Suddenly Chuanzi yelled, “Your Reverence!”

Jiashan stopped and turned around.

Chuanzi held up the oar and said, “Do you say there’s anything else?” He then tipped over the boat and disappeared into the water, never to be seen again.

Gatha by the Boatman Monk

千尺絲綸直下垂

一波才動萬波隨。

夜靜水寒魚不食,

滿船空載月明歸

A thousand-foot fishing line hangs straight down.

One wave moves, ten thousand follow.

The night is still, the water cold, the bait untouched.

The empty boat carries home a full load of moonlight.

Translated by Mary M.Y. Fung and David Lunde

A poem by the 9th-century Zen Master Decheng

A thousand-foot-long fishing line drops straight down.

One wave no sooner rises than it is followed by tens of thousands.

The night is quiet, water is cold, the fish won't take the bait,

The boat returns, empty of fish but full of moonlight.

Translated by Gang Liu, 2010

The poem can be found in Shi Decheng's 釋德誠 Chuanzi heshang bozhao ge 船子和尚撥棹歌 (Songs of Rowing a Boat by the Buddhist Monk Chuanzi; Shanghai: Huandong shifan daxue chubanshe, 1987), p. 11. This book also contains a short biography of Shi Decheng, see pp. 89-91.

Ch'an Master Teh Ch'eng The Boat Monk at Hua Ting

In: Ch'an and Zen Teaching, Series One

by Lu K'uan Yü (Charles Luk)

Rider & Co., London, 1960, pp. 123-128.

Translated from The Imperial Selection of Ch'an Sayings (Yu Hsuan Yu Lu)

[Yuxuan yulu 御選語錄 (Imperial Selections of Recorded Sayings /

Emperor's Selection of Quotations)]

MASTER TEH CH'ENG arrived at Hua Ting in the Hsiu Chou district.

He sailed a small boat, adjusted himself to circumstances and passed his

days in receiving visitors from the four quarters. At the time, as no one

knew of his erudition, he was called the Boat Monk.One day, he stopped by the river bank and sat idle in his boat. An

official (who was passing) asked him: 'What does the Venerable Sir do?'

The master held up his paddle, saying: 'Do you understand this?' The

oflicial replied: 'I do not.' The master said: 'I have been rowing and stirring

the clear water, but a golden fish is rarely found.'When Chia Shan had dismissed his followers, he packed and went

straight to Hua Ting. Master Teh Ch'eng saw him and asked: 'Virtuous

One! At what temple do you stay?' Chia Shan replied: 'That which is

like it does not stay (and) that which stays is not like it.' Master Teh Ch'eng

asked: 'If there is no likeness, what is it like?' Chia Shan replied: 'It is not

the dharma (thing) before the eyes.' Master Teh Ch'eng asked: 'Where

have you learned all this?' Chia Shan replied: 'Neither the ear nor the

eye can reach it.' Master Teh Ch'eng said: 'A good sentence is a stake to

which a donkey can be tethered for ten thousand aeons.' He again

asked:'When a thousand feet of fishing line is let down, the quarry is

deep in the pond. Three inches beyond the hook, why don't you speak?'

Chia Shan (guessed and) was on the point of opening his mouth,

when the master gave him, with the paddle, a blow that knocked him

into the water. When Chia Shan was about to scramble back into the

boat, the master said again: 'Speak! Speak!' Before Chia Shan could

open his mouth, the master hit him again. Thereupon, Chia Shan was

instantaneously enlightened and nodded thrice (in approval and

gratitude).The master said: 'You can play with the silken line at the end of the

rod, but so long as you do not disturb the clear water, the meaning will

be different.'Chia Shan then asked: 'What is your idea about letting down the line

and throwing in the hook?'Master Teh Ch'eng said: 'The line dangling in the green water allows

all ideas of existence and non-existence to float up to the surface until

both become still.'Chia Shan said: 'Your words lead to abstruseness but follow no paths;

the tip of your tongue talks but is speechless.'The master said: 'I have been letting my line down in every part of this

river and only now have I found a golden fish.'(Upon hearing this), Chia Shan closed his ears (with his hands).

Master Teh Ch'eng said: 'It is so! It is so !' and then gave him the following

instruction:'In the future, your hiding place should have no traces and where there

are no traces, you should not hide. I spent thirty years at master Yo Shan's

monastery and understood nothing but this. You have got it now. From

now on do not stay in towns and villages, but search deep in the mountains

for one or two men with mattocks at their sides to continue (the transmission)

and not allow it to be broken off.'Chia Shan took leave of the master but turned back repeatedly to see

(him). Master Teh Ch'eng called out: 'Venerable Sir!' When Chia Shan

turned his head the master held up the paddle and said: 'Do you think that

I still have something else?' Then he upset the boat and disappeared in

the water.* * *

The boat monk sailed a small boat, adjusted himself to circumstances

and passed his days in receiving and enlightening men from all quarters

for it is the duty of every Ch'an master to enlighten and liberate all living

beings. He may use anything he can pick up, such as a paddle in this story,

or a dust-whisk, a cup of tea, a staff, etc.

In reply to the official's question, the boat monk held up his paddle to

show him that in one's daily activities, one should not stray from one's

self-nature which was that which ordered his hand to raise the paddle.

A man of high spirituality would understand the move and become

awakened to the truth. However, the official was deluded and did not

understand it.

When Chia Shan said to his disciples: 'The Dharma-kaya has no form

and the Dharma eye has no flaws', Tao Wu, also an enlightened master,

laughed. This laugh caused a doubt to arise in the mind of the speaker who

asked Tao Wu about his error and was urged by the latter to go to Hu

Ting and call on the boat monk for instruction. What Chia Shan said

to his disciples was not wrong but Tao Wu laughed because the speaker

was merely repeating other people's sayings but did not himself have a

personal experience of the teaching. Chia Shan was urged to go to the

boat monk because there was an affinity between them which could ensure

Chia Shan's enlightenment. (Literally - 'for there existed between the

two a co-operating cause'.)

The boat monk's first question was to probe Chia Shan's understanding

of absolute wisdom (prajna). Chia Shan who had read and probably

learned by heart many sutras, knew that 'staying at a temple' meant

'attachment to a place' and that such attachment to the phenomenal was

wrong and could obstruct his wisdom. So he replied: 'That which is like

the truth does not stay and that which stays is not like the truth for the

truth is all-embracing and does not stay at a particular place.' The boat

monk asked: 'If it is not like that, what is it like?' Chia Shan replied that

what he meant was not the visible and could not be heard or seen. The

boat monk said: 'If you cling to the words with which you have learned

to interpret the truth, you will be held in bondage by them and will never

realize the truth.'

As he was called 'boat monk' and since every boat - called sampan in

China - contained a fishing rod, the master naturally mentioned the line

to teach Chia Shan and said: 'When I let down a thousand feet of line,

I expect to hook a dragon at the bottom of the deep pond but I do not

want to catch a small fish.' This means that he expected to receive a pupil

of high spirituality and not a man of dull disposition.

The sentence 'Three inches beyond the hook, why don't you talk?'

is a literal translation of the text which can also mean 'Beyond the hook

and three inches, why don't you talk?' According to ancient scholars,

that which measures three inches is the tongue which is therefore called

'the three-inch tongue'. The Chinese language favours sentences with a

double meaning and all masters availed themselves of this facility when

probing their disciples. His idea was this: 'Why don't you throw away

all that you have memorized and can be expressed by words and by means

of the tongue? Why don't you talk about that which is beyond hook

(i.e. word) and tongue?'.

As Chia Shan was making use of his discriminating mind to find a

reply and was about to open his mouth, the master gave him with the

paddle a blow that knocked him into the water. The teacher gave the

blow to cut off the pupil's chain of thought. When Chia Shan returned to

the boat, the monk pressed him again: 'Speak! Speak!' and as Chia Shan

was again thinking about a reply, the master hit him once more with the

paddle. The master wanted to press the pupil hard, so that the latter's

mind would have no time to discriminate and to think about an answer.

This time, the boat monk succeeded in wiping out the pupil's last thoughts.

As Chia Shan was stripped of thoughts, his real nature was exposed and

could now function freely without further obstruction. It was now the

self-nature which received the second blow, and when its function could

operate without hindrance, his self-nature manifested itself simultaneously.

Thereupon, Chia Shan realized instantaneous enlightenment and nodded

thrice to thank the master.

Usually when one has no worries, one's discriminating mind gives

rise to all kinds of thoughts, but in time of danger, one will try to save

one's life first. When Chia Shan saw he was about to drown, he immediately

applied the brake to his mind and thus realized singleness of

thought, as taught by Ch'an masters who urged their disciples to hold

firm a hua t'ou. Before receiving the first blow, it was a discriminating

Chia Shan who merely repeated what he had learned to answer the

boat monk's question. After the first blow, it was another Chia Shan

who realized singleness of thought, that is he only thought of saving

his own life, but he still clung to this single thought. The boat monk,

who was a skilful teacher, gave the second blow to disentangle Chia Shan's

mind from this last thought so that it became pure and free from this last

bondage. After the second blow, Chia Shan, now free from discrimination,

became instantly enlightened. It was not the discriminating Chia

Shan but his real self-nature which received the second blow and clearly

perceived the boat-monk's self-nature which struck his own nature.

When the function of Chia Shan's self-nature could operate normally

without obstruction, at that moment his self-nature manifested. This was

the cause of his complete enlightenment.

From the above, we can see that the master was a very skilful teacher

and that the disciple was also a man of very high potentiality. The whole

training took less than ten minutes.

So far, only Chia Shan had been enlightened. What about the enlightenment

of others? Every Ch'an practiser should develop a Bodhisattva

mind before undergoing his training, and if he does not think of the

welfare of others, he will never succeed in his self-cultivation.

Now the master gave his advice as to the disciple's future conduct.

He said: 'You can play with any device or method you like, but if you

do not disturb the clear water, that is if your mind does not give rise to

discrimination, the result will transcend everything.' Chia Shan, who had

only just been enlightened and had not fully recovered from his fright,

asked the master: 'What do you mean by letting down the line and

throwing in the hook?' He meant: 'If the teaching does not rely on words

and phrases, how does one receive and enlighten others?' The boat monk

replied: 'The angler dangles his line in the green water to find out whether

a fish is feeding. If there is a (hungry) fish, it will certainly come to the

baited hook. In future, when you receive disciples, you should use the

same kind of words and phrases that I did a moment ago, to see if they

still hold the dual conception of "existence" and "non-existence", that is

if they still split their undivided self-nature into selfness and otherness,

and teach them until they wipe out all dualisms so that their minds can

become still.'

Chia shan said: 'Your words lead to abstruseness but follow no paths

and the tip of your tongue talks but is speechless.' Here the disciple

praised the master for his marvellous way of teaching because the boat

monk used, in illustration, only words and phrases which did not give

rise to discrimination and could not be clung to by the disciple's mind.

This was really an unsurpassed way of training a pupil.

In return, the boat monk praised Chia Shan's instantaneous enlightenment,

saying: 'I have been letting my line down in every part of this river

and only today have I caught a golden fish.'

Upon hearing his master's words of praise, Chia Shan closed his ears,

for even these words of praise were basically wrong because self-nature

can neither be praised nor censured. Instead of listening to these words, he

found it better to close his ears as the best way to preserve the reality and

brightness of his self-nature. The boat monk confirmed his pupil's correct

conduct and said: 'It is so! It is so!' These words were the best praise

a master could give to his enlightened disciple.

Then, the boat monk gave his disciple the following instruction: 'In

future, your hiding place should have no traces, and where there are no

traces, you should not hide.' In other words, 'You have now realized the

Dharma-kaya which is immaterial and leaves no traces. However, you

should refrain from giving rise to the idea of "no traces" or absolute voidness

within which you should not abide, for in that case, you would give

rise to the idea of "no traces", both "traces" and "no traces" being in the

realm of dualism and having no place in absolute reality. I spent thirty

years with my master Yo Shan and learned only this truth which you have

now acquired.'

The master said further: 'From now on do not stay in towns and villages

where you will not fmd men of high spirituality who can understand

your teaching. You should go to places where men have no chance of

seeking fame and wealth because there only can you look for disciples

who are either wholly or at least half bent on the quest of truth. These are

the people you should search for and receive to enlighten them so as to

ensure the continuity of our Sect.'

Literally the sentence reads: 'But -you should- deep in the mountains

search for one and a half (man) with a mattock by his side.' The Chinese

idiom 'one or a half man' is equivalent to the Western saying, 'one or

two men'. Therefore, another interpretation is: 'You cannot expect to

enlighten more than one or two men for Ch'an is not so easy to

understand. It will suffice to enlighten one or two people to continue

our sect.'

Chia Shan left the boat monk but repeatedly turned his head to see

him. The master called him and held up the paddle, saying: 'I have only

this (paddle) and do not think that I still have something else.' This means:

'I have only this, that is that which held up the paddle and I have taught

it to you. I have nothing else to teach you and do not give rise to any

further suspicion about it.'

Then the master overturned his boat and disappeared in the water to

show that when one is enlightened, one is free to come and free to go.

This is only possible after one has obtained enlightenment. This was also

to show Chia Shan that the transmission was actually handed down to

him and that he should take over the master's mission which was now

ended on this earth, but would begin in another world where other living

beings were waiting for him.

The Boat Monk

by William Bodri

http://www.meditationexpert.com/zen-buddhism-tao/z_boat-monk_teh-cheng.htm

I love the Zen story of the Boat monk. It expresses the Zen high literary style, and the beauty of the dharma.

Seems that a group of monks attained some degree of the Tao under a famous Zen teacher, Master Yao-shan. One of them was Teh-cheng and his dharma brothers were Yun-men and Tao-wu. Master Teh-cheng knew he didn't have the personality to teach a large number of people or run a monastery, so he told his brothers to send him someone of exceptional talent when they found one rather than open up a teaching center himself.

As is the rule, his job would also be to transmit the dharma to a qualified student if he could find one, but without a teaching center, he had no way to attract a student. Therefore his dharma brothers would have to send someone who had the karmic affinity with Teh-cheng for awakening. So he told them, "You know where I am staying. If you find a student of sharp potential, send him to me so that I may transmit the dharma."

Years later, it just so happened that Teh-cheng's dharma brother Tao-wu was attending a lecture by a famous monk, named Chia-shan, who already had a great following. Chia-shan knew all about the dharma and was extremely eloquent. He could respond to every question with the proper words, and yet he lacked the dharma eye...he lacked any true stage of attainment. Ask him any question and he could respond with the right words ... but without the dharma eye, everything was actually wrong because it could enlighten no one. He knew the words but did not know the real meaning -- he had not achieved it.

His case was like the intellectuals today who study the Bible, Koran, Buddhist sutras, Torah, or any such book or sets of books, know all the perfect words to use so that they sound as if they are in accord with the traditional teachings, and yet everything they say lacks any touch with True Reality. Why? Because those folks have no cultivation attainment themselves. They are dogma literalists rather than enlightened sages. So while they may be intellectually brilliant they are spiritually bereft, and cannot lead anyone to liberation.

That's the state of the world. That's 99.999999999999% of teachers and religious professionals out there.

So while attending the lecture, Master Tao-wu just kept himself quiet and concealed, but he snickered when Chia-shan answered a question correctly ... in order to attract attention. After it was over, Chia-shan respectfully approached master Tao-wu and asked what mistake he had made that his elder had done so.

Tao-wu replied, "You answered correctly, it's just that you've never been taught by a good teacher. I never explain things. If you want to learn, you must go to visit the boatman's place at the city of Hau-ting (where the Boatman Monk Teh-cheng was staying)."

Now because he really was interested in self-improvement, Chia-shan set off right away. This, in itself, shows he was of extraordinary character and not too full of himself. Chia-shan was right in theory, but did not have a real experience of the dharma, yet didn't know it. He thought he was right, but also suspected that he was wrong, that he was missing something though everything he said was correct and according to the scriptures. Amazingly, he was willing to take advice and was anxious to find the answer despite already being established and having a great reputation, so off he went.Would you do that?

Now at the location, the dharma brother Teh-cheng had settled into a job ferrying people across a river, and had done so for several decades waiting for a good student. No one knew of his high stage of attainment. When the young monk arrived, with one look he knew that he had been cultivating and had some ability, but needed to be awakened to a true direct experience of the dharma. He needed a real, direct experience of the Tao. He knew all the right words, the sutras, the dharma and so forth, but he was clinging to all these explanations and his conceptualizations. He had become an intellectual master rather than reality master. He could not let go of them to realize no-self, no-ego, emptiness. Therefore he had not attained the Tao.

Upon meeting young master Chia-shan, who knew all the correct words but had no direct taste of reality, Teh-cheng opened up the conversation by asking, "What temple do you dwell in, oh virtuous one?"

Chia-shan answered with words that point to the Tao, though of course he did not have that stage of attainment: "I do not dwell in a temple. Dwelling is not like it."

Why did he say this? Because the original nature is not a state, and if you dwell or abide in any state it is NOT the Tao. Chia-shan was saying he understood the Tao by answering in such a way because a regular monk would simply have mentioned the name of his city or monastery.

The boatman then asked, "It is not like what?"

Chia-shan once again correctly answered the correct intellectual response, "It is not the phenomena before our eyes."

Because Chia-shan kept answering correctly, but without without possessing the true dharma experience himself, it was like someone who would respond with the right scriptural retort from the Bible ... though everything said was everything right and you could not find any fault with it, you could tell they were wrong. I'm sure you've had that experience because it is hard to explain.

A little bit disgusted at these canned responses, the Boat monk Teh-Cheng then asked, "Where did you learn all this (way of answering)?"

Chia-shan answered, "It is not something that the eyes or ears can reach," meaning it ultimately comes from the Tao. This time Chia-shan replied in such a way that you could take it as a smirk, with the hidden meaning being, "I know this and you don't? Who are you that you don't know these things?"

With that response, the Boatman monk then uttered a famous line, "A fitting sentence can be a stake that tethers a donkey for 10,000 aeons."

In other words, if you just cling to scripture, or intellectualization, or the words of this or that holy text without arriving at a genuine experience of the true meaning, if you don't experience the original nature, you will tie yourself up in ignorance (non-enlightenment) for aeons and never become free. Why? Because you cling to the intellect, in which case you are wrong. Words will not save you, scripture will not save you. Only cultivation practice and realization will save you!

How many people follow this pattern today? They quote the Torah and cling to it, all the while being correct in words, but WRONG. They cling to the Bible, reciting verses and sentences correctly, and yet they lack any attainment or any means for getting anywhere. They cling to the Koran, the Buddhist sutras, Taoist works and they are all wrong. They never fathom the meaning of the texts. They never reach enlightenment or samadhi or any genuine stage of attainment. They can talk about things all they want, but these are just intellectuals rather than spiritual leaders, people who know a lot about religious things but cannot lead you to the Tao. This is all you find today in churches, temples, mosques and monasteries. No one has the enlightenment eye, or even an inkling that it exists ... and they are even oblivious on how to get there.

"A fitting sentence can be a stake that tethers a donkey for 10,000 aeons" -- Master Teh-cheng was saying that Chia-shan was clinging to the dharma and relying on verbal tricks, and that this was stupid. It would get you absolutely nowhere on the path of true spiritual practice and striving and progress. It was just mental games, verbal tricks and memorization. REAL accomplishment comes from the cultivation practice of letting go and detaching from the realm of mentation to get to the substrate underneath it and EVERTHING.

"A fitting sentence can be a stake that tethers a donkey for 10,000 aeons" ... Chia-shan was stunned at this reply.

Zen master Teh-cheng then said, "The fishing line is hanging down a thousand feet, and the intent is deep in the pond. You're just three inches away from the hook. Why don't you say something?"

He was saying, "You've done so much meditation work your life and are so close you're ready to reach it. Why not say something expressing your original nature?"

Chia-shan was standing there, his mind emptied a bit because of the shock, and was just about to say something intellectual again when the Boat monk hit him with his oar and knocked him into the water.

Wham!

Chia-shan had just been ready to open his mouth again and say something that was in the scriptures when the Boat monk knocked the daylights out of him and he flew into the water.

As soon as Chia-shan's head popped up above the water again, the Boat monk once again shouted, "Speak! Speak!" and just as Chia-shan was about to open his mouth again, Wham! ... the Boat monk hit him again.

Now if you've had any sudden taste of emptiness where everything empties out (a religious experience), you can understand what happened next. Here's a man with a belly full of learning and it's all suddenly knocked out of him. He's been thrown into the water, he's worried for his life, and all his false thoughts have been whacked away.

That's the method the Boat monk used with Chia-shan.

Chia-shan could talk about anything in the dharma ... Consciousness only, the three Buddha bodies, skandhas, True Thusness, prajna wisdom, EVERYTHING. He understand all this but couldn't let go of it, so the Boat monk knocked him into the water to help him let go of everything he was clinging to. Even so, when asked to speak, Chia-shan was ready to spit out the dead scriptural words again, so Teh-cheng hit him again. When for the third time his head rose above the water, this time his mind had emptied out and he and become enlightened, so Chia-shan quickly nodded his head three times in quick succession to show Teh-cheng he had got it and he didn't need to be hit again.

Of course you cannot just hit someone to enlighten them. Don't think it's so easy. Chia-shan not only KNEW the dharma intellectually, but had spent his life meditating and had achieved some degree of emptiness, but just couldn't let go of his intellectualizations to see the path, to see the whole thing. He was close because of his previous attainments in meditation, but still clinging. He already had achieved a deep basis of cultivation beyond just studying, because of prolonged meditation work, and that basis is why Tao-wu sent him to the Boat monk. He was prepared....don't think someone can just whack you or slap you and you get it. Without countless years of meditation work, that would just get you a lawsuit today.

Master Teh-cheng was able to transmit the dharma only because Chia-shan had already spent years mixing practice with study. Master Teh-cheng was able, through the expedient means of whacking him, to help Master Chia-shan let go of everything and see the Path, see the Tao, realize self-enlightenment. If Master Chia-shan had not been a meditator, however, none of this would have been possible. So don't think that just studying scriptures and sutras -- of any kind -- will do it. You have to do the meditation work, open up your chi channels, chakras and so forth. You have to cultivate samadhi, but none of that is the Tao. It's just a preparation because those are all still illusory realms and false stations. They are not ultimate or supreme. They are there to help you clear out in a progressive sense, but when you reach enlightenment there are no stages -- you just let go of everything in one fell swoop. That's why it's called breaking through the conception skandha.

Upon being hit with the oar when in the water, Chia-shan GOT IT. His years of preparation and study, together with the Boatman's excellent skillful means, enabled him to let go, empty out and see the Tao. If you know the theory, that's why the story is so beautiful, so wonderful. But then, while still in the water, Chia-shan asked, "If you throw away the hook and line, what is your intent, teacher?"

In other words, Chia-shan then had doubts and asked about functioning. He was asking, "What about the methods for making an effort in the realm of existence if everything is empty... What do you do about them?"

Master Teh-cheng replied, "The fishing line hangs in the water, floating to set the meaning of existence and non-existence." In other words, don't talk of emptiness and don't talk of existence. Neither is right, and thus you don't cling to either and you can do what you want independently. You are free and liberated. Cause and effect still operates amidst phenomena, but you do not cling to them or the process. You realize the inherent fundamental emptiness of phenomena but you do not cling to it either. You are independent and free.

Master Chia-shan then said, "Words carry the mystery but they have no road. The tongue speaks without speaking." In other words, speaking is the same as non-speaking, emptiness and existence are equivalent to one another.

Master Teh-cheng was VERY happy at hearing this because then he knew Chia-shan had got it. He knew that Chia-shan had finally realized the Truth and was speaking from experience rather than from some scripture he had memorized and studied. So Teh-cheng then said, "After having fished through all these rivers [having piloted this ferry day after day for decades wanting to carry someone over to the other side], I have finally encountered a golden carp [enlightened person].

Chia-shan covered his ears at hearing this, and master Teh-shan said in response, "That's right, that's right!"

Then he told Chia-shan, "From now on you must leave no tracks where you hide yourself. But you must not hide yourself where there are no tracks."

He expressed in a high literary style many meanings: that Chia-shan must continually cultivate that state of no-thought/emptiness he had just achieved wherein there are no tracks. Furthermore, he must go somewhere where no one knew who he was, and leave his fame behind, and thus go into hiding in order to finish his cultivation. He also said that Chia-shan must not remain clinging to emptiness either, for that was also wrong.

The Boat monk then continued, "I was with Zen master Yao-shan for 30 years and I only took away this which you have just experienced/realized. Nothing more. You have just attained it. This is the meaning of all the teachings and nothing more. It's nothing else either than experientially realizing this. In the future you should not live in towns or villages but go deep into the mountains, find one or two people to continue the teaching and do not let it be cut off."

Chia-shan was out of the water by this time, and since the dharma had been transmitted, he started off to return home. The whole thing happened just this quickly, the dharma had been passed, and there was nothing more to be done. But for a moment Master Chia-shan doubted that was all and so he turned around, wandering if there was something else he was missing, if it all came to just this?

Upon seeing this, Zen master Teh-cheng shouted back to him, holding up an oar and saying, " Did you think there was something else? " Then he capsized the boat and disappeared under the water to show there was nothing else. You see, if you cling to all the pageantry of Tibetan Buddhism, you are wrong. It's just an expedient method created to help you REALIZE THIS. If you cling to the Torah or Bible, you are wrong. It's just to help you lay a foundation so you can experientially realize this. Nothing in the universe is absolute. The wind, the rocks, the flowers are all singing the dharma to help you awaken.

The meaning of Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Buddhism, Sikhism, Taoism, Confucianism, yoga, alchemy and all the religions is to realize our fundamental nature. All the ceremonies, scriptures, prayers, and practices are to enable you to experientially realize THIS. That's the purpose of all the scriptures.

What else did you think it was about? Some ceremony or special belief?

Now you finally know. Cultivate!

三十年来海上游 , 水清鱼现不吞钩 。 钓竿砍尽重栽竹 , 不计功程得便休 。

[Csuan-ce Tö-cseng, a révész szerzetes verse]

Harminc éven át tengersok habot szeltem

Van hal a vízben, de nem harap horogra

Horgászbotom eltört, bambuszok hajtanak

Nem várok semmire, nyugalomra leltem

Terebess Gábor fordítása

A csónakos szerzetes

In: Zen történetek. Ford., szerk. és vál. Szigeti György, [Budapest] : Farkas Lőrinc Imre Kiadó, 1996, 19-22. oldal

[Szigeti György fordításában a kínai nevek a koreai olvasat magyar átírásában szerepelnek, pl. Tö-cseng = Dok Szong]

Régen Kínában a nagy Jak Szán zen mesternek két fő tanítvá-

nya volt: Un Am és Dok Szong. Ók maguk is zen mesterekké

lettek, mert Jak Szán mindkettőjüknek átadta a Tant. Un Am

hatalmas, fáradhatatlan ember volt, olyan hanggal, mint a

bronzharang, és ha felnevetett, rázkódott a föld. Tanítóként

hamar nagy híre járt, tanítványok százai jöttek hozzá tanulni

Dok Szong pedig aprócska, vékony ember volt, olyan visszafo-

gott természettel, hogy mások alig vették észre. Csak néhanap-

ján tett vagy mondott olyasmit, ami napokig visszhangzott a

tanítványok tudatában.Amikor Jak Szán zen mester meghalt, Dok Szong elment Un

Am-hoz, és így szólt:

- Nagy zen mester vagy, sok tanítványod, sok templomod

van. Ez ellen nincs semmi kifogásom, de az én utam más. Fo-

lyókhoz, hegyekbe, felhők közé vezet. Ha elmentem, kérlek,

küldj utánam egy tanítványt, hogy lerójam tartozásomat Mes-

terünknek.Ezekkel a szavakkal Dok Szong elindult Hva Dzsong tarto-

mány felé. ott letette szerzetesi ruháját, hosszúra hagyta a ha-

ját, vett egy apró csónakot, és azzal hozta-vitte az embereket

a folyó egyik partjáról a másikra. Így Dok Szong egy egyszerű

révész életét élte, teljes névtelenségben és szabadságban.Sok év telt el. Egy közeli tartományban, Hon Am-ban élt egy

fiatalember, akit Szon Hejnek hívtak. Kilencéves korában lett

szerzetes, és azóta lelkiismeretesen tanulmányozta a szútrákat.

A tartomány minden elsőrangú tudósánál tanult, és a nagy jár-

mű sokkötetnyi szövegében tökéletes jártasságra tett szert. Vé-

gül mint az ország egyik legnagyszerűbb Dharma tanítóját tisz-

telték, és az emberek mindenfelől sereglettek templomába gya-

korolni s előadásait hallgatni.Egy nap egy különösen jó előadás után, valaki megkérdezte:

- Mester, kérlek, magyarázd el nekem: mi a Dharma-test?- A Dharma-test nem létezik - válaszolta Szon Hej.

- És mi az igazlátó szem? - hangzott el a második kérdés.

- Az igazlátó szem hiba nélküli - válaszolta Szon Hej.

Hirtelen a terem hátsó részéből hatalmas kacagás hallat-

szott, olyan erősen, hogy beleremegett a föld. A beálló döbbent

csendben Szon Hej várt egy pillanatig, majd lelépett az emel-

vényről, és a terem közepén húzódó szabad téren át a terem vé-

gébe sétált. Megállt egy öreg szerzetes előtt, aki az előbb neve-

tett, meghajolt, és megkérdezte:

- Bocsásson meg, tisztelendő uram, de hol követtem el hibát?

A szerzetes mosolygott, értékelve Szon Hej alázatát.- A tanításod nem helytelen - mondta -, de még csak nem is

sejted a végső igazságot. Egy éles szemű mester tanácsára van

szükséged.- Lenne szíves tanítani engem? - kérdezte Szon Hej.

- Elnézésed kérem, de ez szóba sem jöhet. Miért nem mész

el Hva Dzsong tartományba? Van ott egy révész, aki megmu-

tatja neked az utat.- Egy révész? Miféle révész lehet az?

- Oly hatalmas, hogy felette nincs hely a tetőnek, és oly pa-

rányi, hogy alatta nincs hely amnek. Lehet, hogy úgy néz ki,

mint akármelyik révész, de menj és beszélj vele. Győződj meg

róla.Így hát Szon Hej otthagyta sok-sok tanítványát, letette szer-

zetesi köpenyét, és elindult Hva Dzsongba.Több nappal később Szon Hej megtalálta a csónakos embert.

Öreg volt, elnyűtt ruhában, és tényleg egyszerű révésznek tűnt.

Csak biccentett, amikor Szon Hej a csónakba lépett. Párat hú-

zott a lapáttal, majd hagyta a csónakot sodródni, és így szólt:

- Tiszteletreméltó uram, mely templomban időzik?Szon Hej meglátta a kérdésben rejlő kihívást. Felült, figyelt,

és ezt mondta:

- Ami hasonlít hozzá, nem tartózkodik; ami tartózkodik,

nem hasonlít hozzá.-Akkor mi lehet az? - kérdezte Dok Szong.

- Nem az, amit látsz.

- Hol hallottad ezt?

Idáig Szon Hej becsülettel állta a sarat, de a mester tökélete-

sen látta a tudatát. Majd hirtelen elkiáltotta magát:

- KACU!Erre Szon Hej nem tudott mit mondani. Pár pillanatig csend

volt. Akkor a mester megszólalt:

- Még a legigazabb állítás is földbe vert karó, melyhez tíz-

ezer világkorszakon át ki lehet pányvázva a szamár.Ekkor Szon Hej teljesen elvesztette lába alól a talajt. Halott-

sápadt lett, alig kapott levegőt.A mester ismét megszólalt:

- Ezer méter zsinórt engedtem a vízbe, a hal itt ficánkol a

horog szakállán. Miért nem szólsz?Szon Hej kinyitotta a száját, de egy hang sem jött ki a torkán.

Ekkor a mester kezében süvöltve lendült az evező, és eltalálta,

olyan erővel, hogy Szon Hej a vízbe repült. Mélyen lemerült, és

amikor feljött, fújtatva és köpködve, a hajó oldalába kapaszko-

dott. Ahogy felhúzódzkodott, a mester rákiáltott:

- Mondd meg! Mondd meg! - és visszasújtotta a folyóba.Ekkor Szon Hej tudata az evező kemény ütésére kitárult, és

mindent megértett.Amikor feje a víz fölé került, taposni kezdett, és háromszor

bólintott. A mester örömtől sugárzó arccal nyújtotta az evezőt,

és visszahúzta Szon Hejt a csónakba. Pár percig ültek és nézték

egymást. Akkor a mester ezt mondta:

- Játszhatsz a selyemfonállal a rúd végén, amíg nem zava-

rod meg a tiszta vizet, mindent jól csinálsz.- Mit akarsz elérni ezer méter zsinórral?

- Az éhes hal egyszerre nyeli le a horgot és a csalit - felelte

a mester. - Ha létben és nemlétben gondolkodsz, elkapnak, és

megfőznek vacsorára.Szon Hej nevetett, és így szólt:

- Egyetlen szavadat sem értem. Látom, hogy mozog a nyel-

ved, de hol van a hang?- Hosszú évekig halásztam ebben a folyóban, de csak ma

fogtam aranyhalat.Szon Hej a fülére csapta a kezét.

- Ez az. Olyan, mint ez. Milyen csodálatos! - folytatta a mes-

ter. - Szabad ember vagy. Akárhová mész, ne hagyj nyomot. Jak

Szán mester mellett évekig nem tanultam mást, csak ezt. Te

most megértetted, én pedig leróttam tartozásomat.A két ember egész nap és egész éjszaka a vízen volt. Beszél-

gettek és hallgattak. Hajnalban kieveztek a partra, és Szon Hej

kiszállt a csónakból.- Viszontlátásra - köszönt el tőle a mester. - Többet ne gon-

dolj rám. Minden más szükségtelen.Szon Hej elindult. Kis idő múlva megfordult, hogy utoljára

visszanézzen. A mester a folyó közepéről integetett neki, azu-

tán hintázni kezdett előre-hátra, míg a csónak fel nem fordult.

Szon Hej figyelte a vizet, hol bukkan fel a mester feje, de nem

látta sehol. Csak a felfordult csónakot vitte az ár a szeme előtt,

lassan, lefelé, amíg teljesen el nem tűnt.