ZEN FESTMÉNYEK ZEN PAINTING

« Zen illusztrációk

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

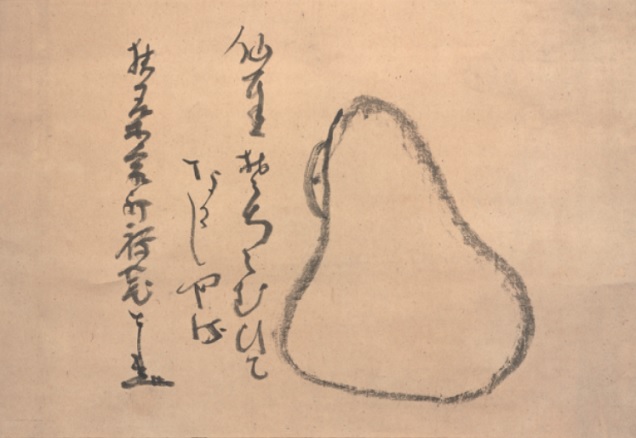

仙厓義梵 Sengai Gibon (1750-1837)

Zenga 禅画

Two Self-portraits

Personal seal

Honorific name: Fumonentsu Zenji. Pen name: Hyakudo, Kyohaku, Tenmin, Muho-sai, Taiho, Ayo. Dharma transmission from Gessen Zen'ne. After spending time preaching around the countryside, he became the abbot of Shofuku-ji at the age of 39. His works conveyed Zen teachings with light-hearted wit and often self-mocking humor. They were easy to interpret and were widely accepted and loved by the people. He now has an international reputation.

PDF: Sengai, The Zen Master

by Daisetz T. Suzuki

Faber & Faber Ltd, 1971

PDF: Sengai, the Zen Master: paintings from the Idemitsu Museum of Art, Tokyo

PDF: Zen Paintings in Edo Japan (1600-1868): Playfulness and Freedom in the Artwork of Hakuin Ekaku and Sengai Gibon

by Aviman, Galit

Ashgate Publishing, 2014

PDF: Sengai: Master Zen Painter

by Shōkin Furuta (1911-2001)

Translated, Adapted, and with Notes and Commentaries by Reiko Tsukimura

Kodansha International (JPN), 1st ed, London, Japan, 2000 Tokyo, 2000

PDF: Sengai Stories

Translated by Peter Haskel

2003

PDF: Zen Master Tales

Stories from the Lives of Taigu, Sengai, Hakuin, and Ryokan

by Peter Haskel

Shambala, 2022

További képek:

http://www.asiamodena.it/appuntiyoga/ay/008/ay8.2.html

http://record.museum.kyushu-u.ac.jp/sengai/

http://www.wikipaintings.org/en/sengai/

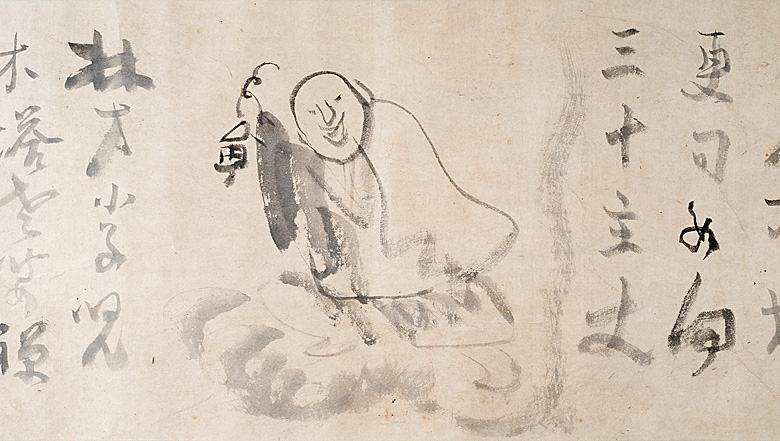

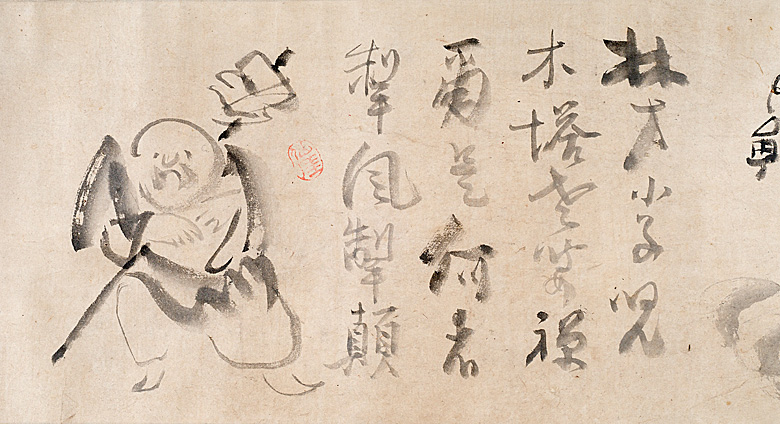

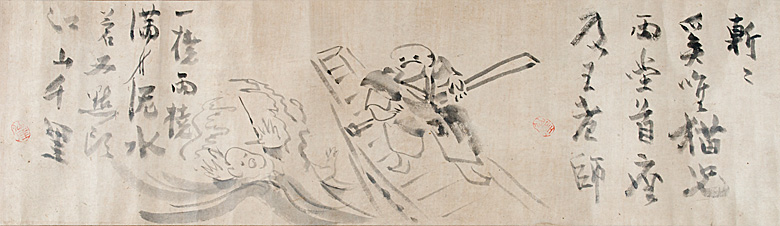

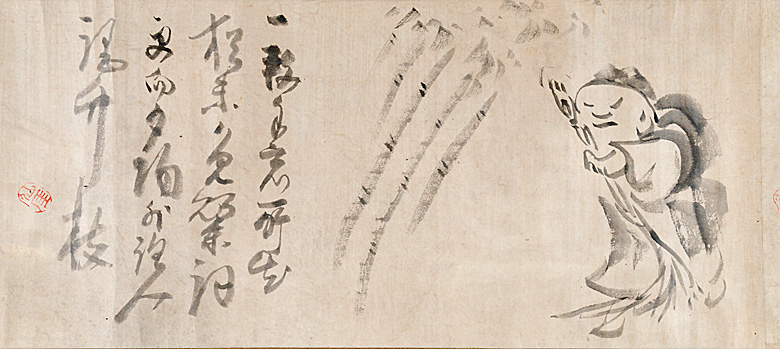

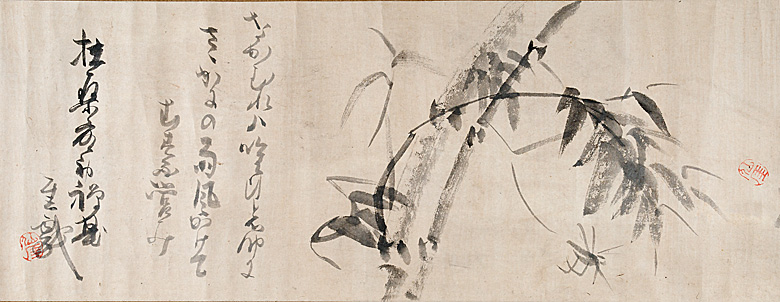

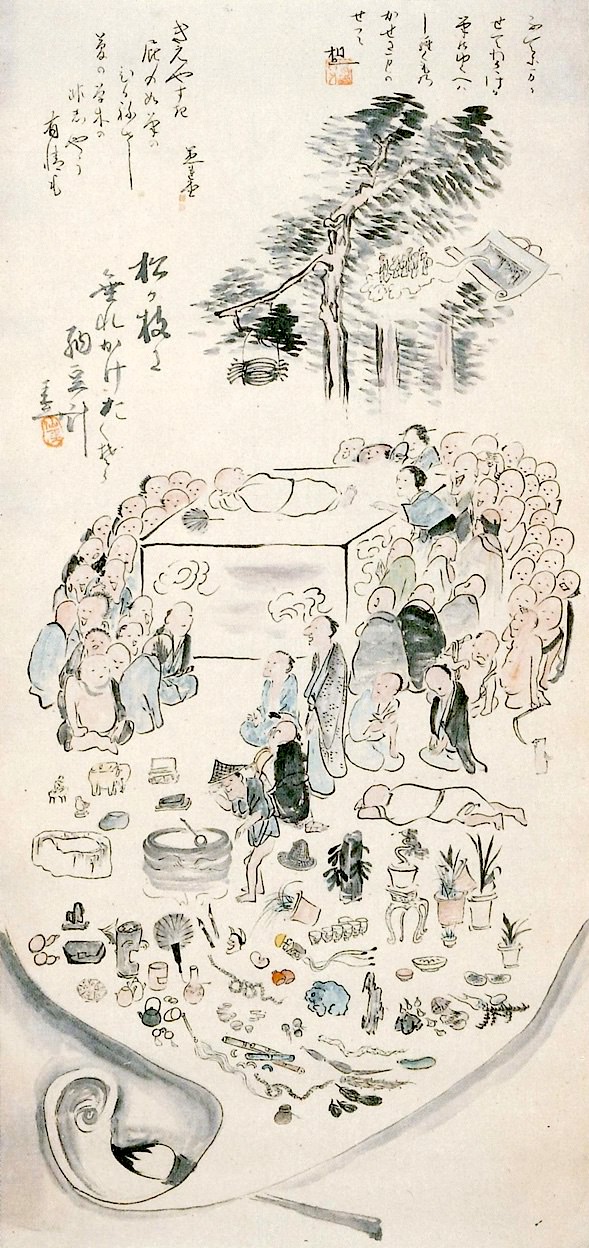

Famous moments in the lives of Zen monks

Signed 扶桑最初禅窟 厓義 Fusō saisho zenkutu Gai gi, sealed Sengai

Handscroll; ink on paper

28.3 x 651cm.

Wood box signed and authenticated by Higashiyama Sahen (Takeda Mokurai; 1854-1930), 4th abbot of Kenninji Temple

萬葉庵 the Manyo'an Collection

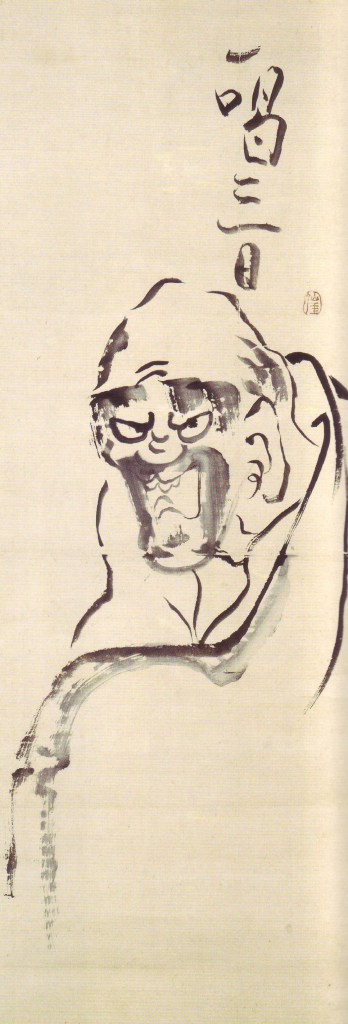

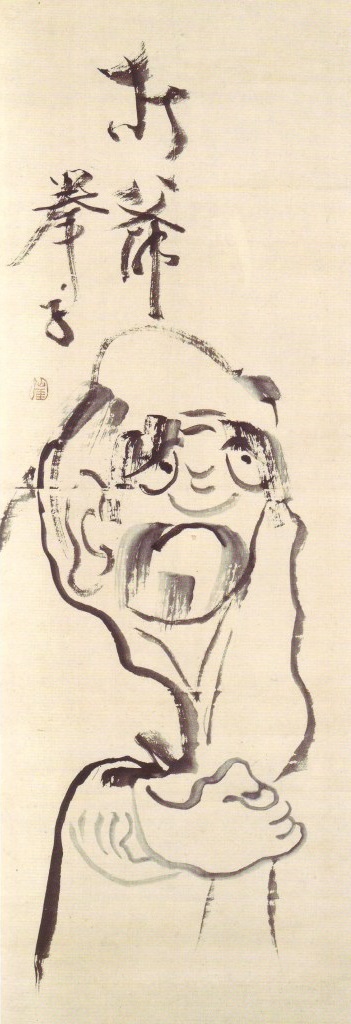

Bodaidaruma 菩提達磨 Bodhidharma, Putidamo (?-532/5)

|

|

|

A special transmission outside the scriptures; Translated by D. T. Suzuki |

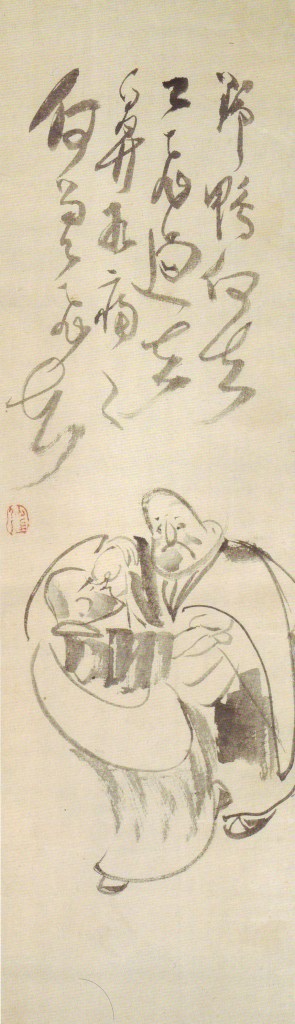

Daikan Enō 大鑑慧能 Dajian Huineng (638-713)

The Fifth and the Sixth Patriarch of Zen Az ötödik és a hatodik zen pátriárka |

|

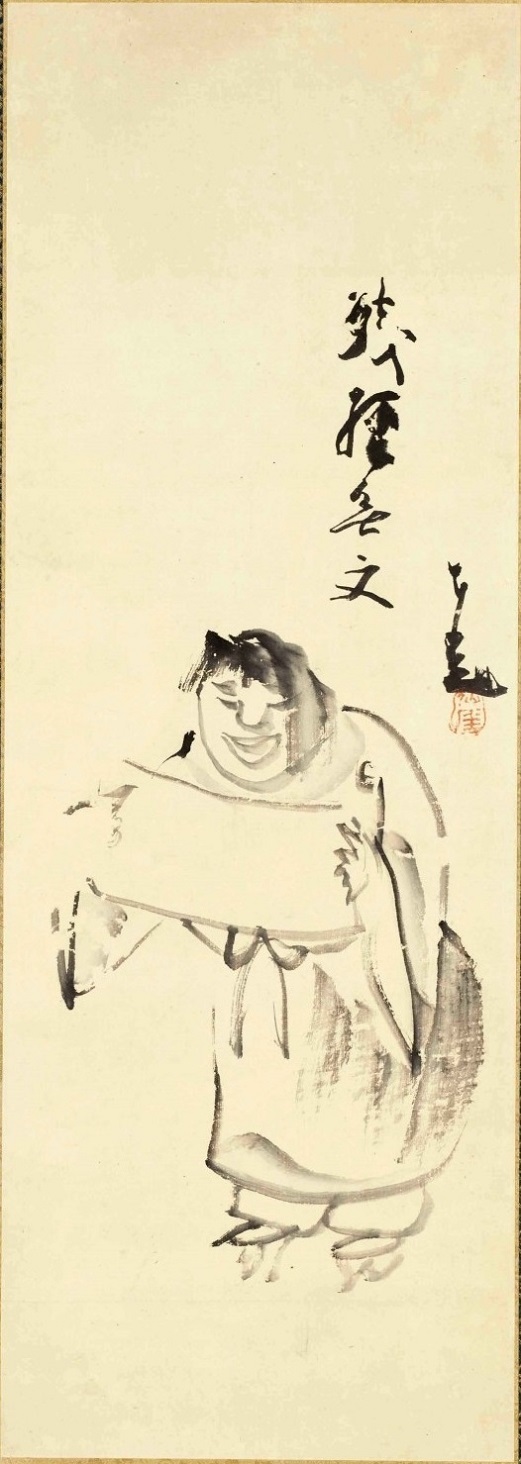

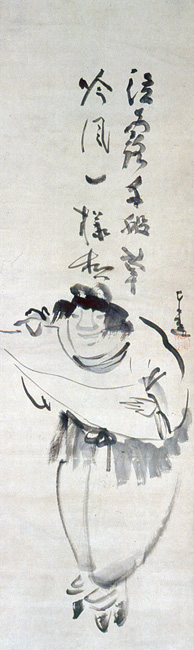

Hotei oshō 布袋和尚 Budai heshang

【絵画データ】 |

|

|

|

Baso Dōitsu 馬祖道一 Mazu Daoyi (709-788)

|

|

|

|

Hyakujō Ekai 百丈懷海 Baizhang Huaihai (720-814)

Baizhang and the Fox (Wumenguan, Case 2)

「百丈野狐」

Once when Pai-chang gave a series of talks, a certain old man was always there listening together with the monks. When they left, he would leave too. One day, however, he remained behind. Pai-chang asked him, “Who are you, standing here before me?”

The old man replied, “I am not a human being. In the far distant past, in the time of Kāśyapa Buddha, I was head priest at this mountain. One day a monk asked me, ‘Does an enlightened person fall under the law of cause and effect or not?' I replied, ‘Such a person does not fall under the law of cause and effect.' With this I was reborn five hundred times as a fox. Please say a turning word for me and release me from the body of a fox.”

He then asked Pai-chang, “Does an enlightened person all under the law of cause and effect or not?”

Pai-chang said, “Such a person does not evade the law of cause and effect.”

Hearing this, the old man immediately was enlightened. Making his bows he said, “I am released from the body of a fox. The body is on the other side of this mountain. I wish to make a request of you. Please, Abbot, perform my funeral as for a priest.”

Pai-chang had a head monk strike the signal board and inform the assembly that after the noon meal there would be a funeral service for a priest. The monks talked about this in wonder. “All of us are well. There is no one in the morgue. What does the teacher mean?”

Rinzai Gigen 臨濟義玄 Linji Yixuan (?-866)

|

|

|

In dealing with his disciples, Te-shan resorted to the rod as frequently as Lin-chi resorted to the shout, as evidenced by the current saying, “Te-shan's rod, Lint-chi's shout.” Once Te-shan announced to his assembly, “If you speak rightly, I will give you thirty blows. If you speak wrongly, I will also give you thirty blows.” When Lin-chi heard about this utterance, he said to his friend Lo-p'u, “Go to ask him why the one who speaks rightly should be given thirty blows. As soon as he begins to strike, catch hold of his rod and push it against him. See what he will do.” Lo-p'u acted accordingly. As soon as he put the question, Te-shan started to strike him, and he caught hold of the rod and made a violent thrust against him. Thereupon, Te-shan returned quietly to his room. When Lo-p'u came back to report to Lin-chi, the latter said, “From the very beginning I have had my doubts about that fellow. Be that as it may, do you recognize the true Te-shan?” As Lo-p'u fumbled for an answer, Lin-chi gave him a beating. John C. H. Wu, The Golden Age of Zen |

|

|

|

|

「臨済図」 |

|

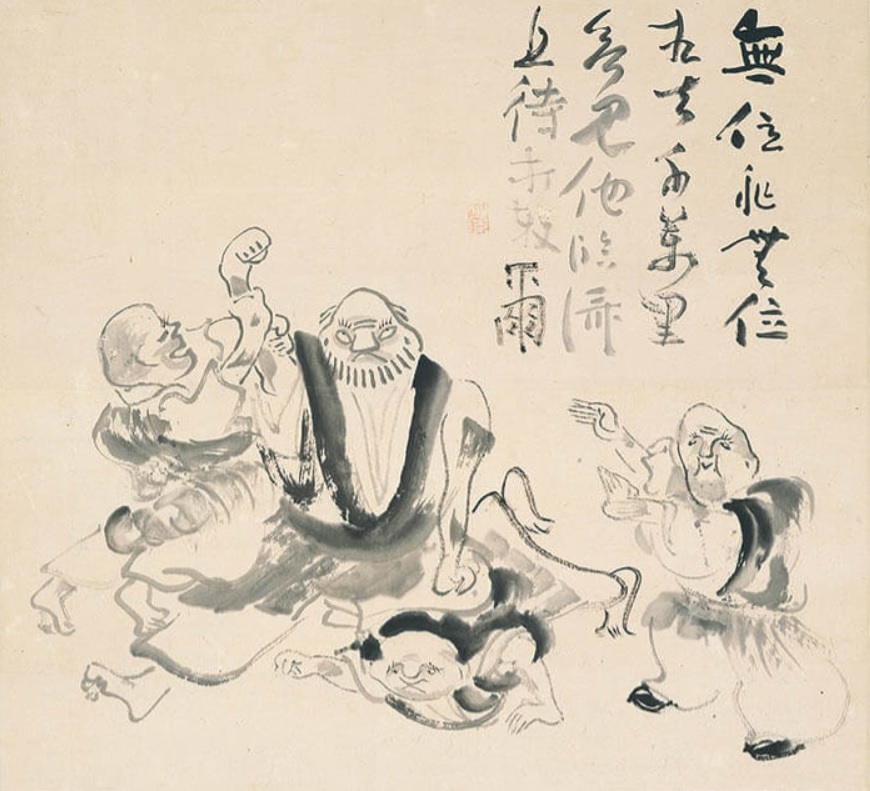

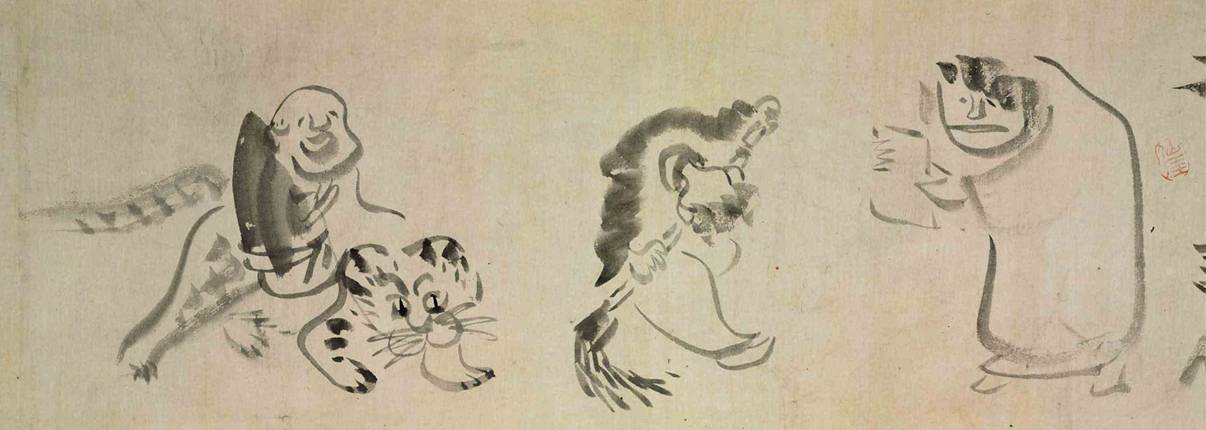

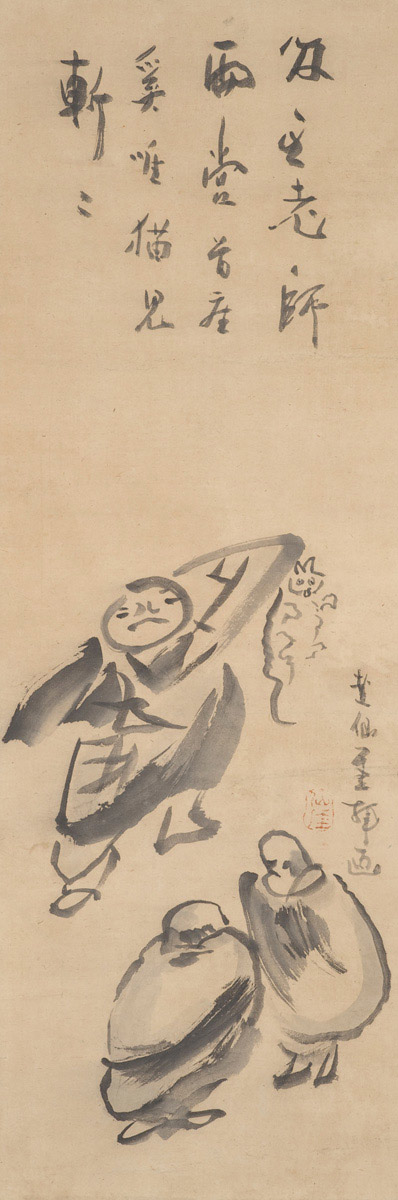

Kanzan & Jittoku & Bukan (寒山 Hanshan & 拾得 Shide & 豐幹 Fenggan, active 627-649)

|

|

|

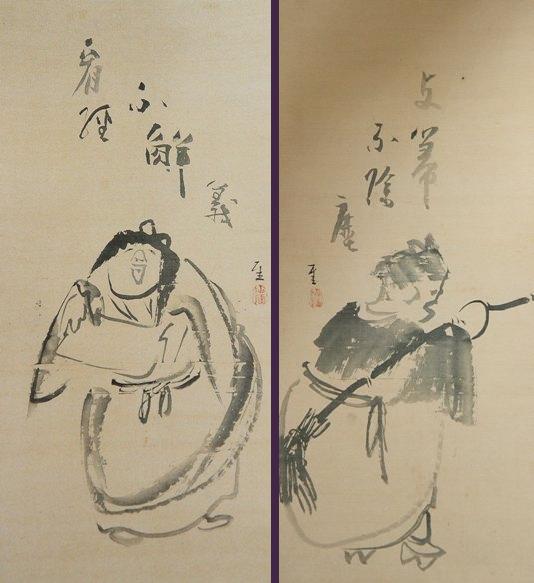

Kanzan Jittoku

87.6 x 30.7 cm

LACMA (Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

Kanzan Jittoku

Edo Period (1615-1867 A.D.)

Hanging scroll(s), ink on paper

94 x 29 cm

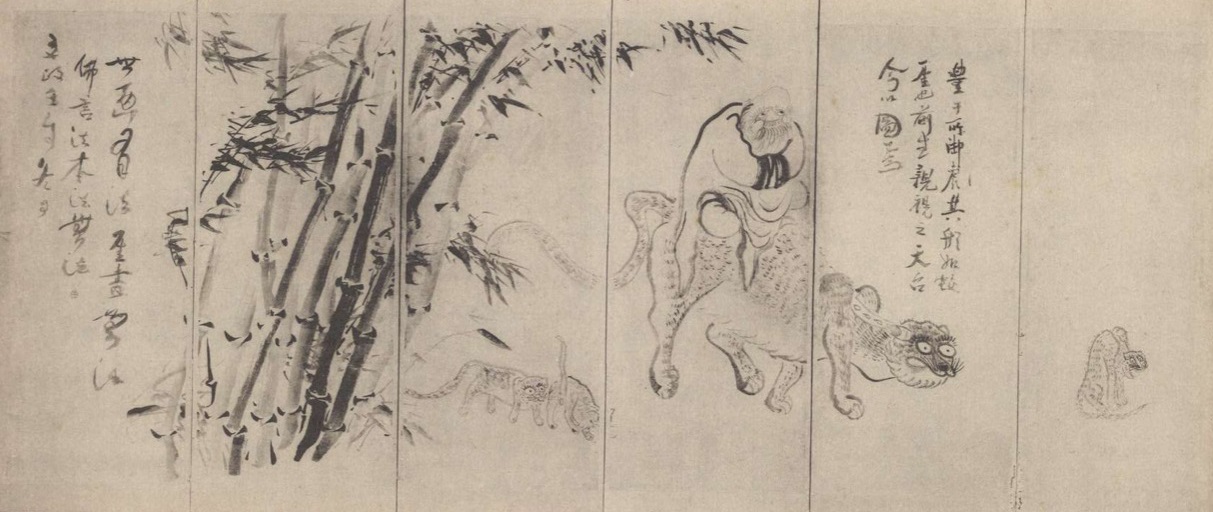

豐幹 Fenggan & 拾得 Shide & 寒山 Hanshan (Bukan & Jittoku & Kanzan)

豐幹 Fenggan (Bukan)

拾得 Shide & 寒山 Hanshan (Jittoku & Kanzan)

「 寒山拾得 ・ 豊干禅師図屏風 」 仙厓筆 6 曲 1 双

文政 5 年 (1822)

各縦 148.4cm 横 363.4cm

福岡・幻住庵

数多い仙厓作品のなかでも最大級かつ最高傑作として定評のある作品で、73歳のときの作です。豊干は中国・唐代の僧で、虎にまたがって寺内をわたり歩くなどの奇行で知られ、寒山と拾得は、豊干禅師に養われたとされる 隠者 です。虎にまたがる豊干は、長谷川等伯の作品にもみられますが、子虎たちを引き連れて歩く姿は、ユニークなこと、この上ありません。人物や親子の虎のヘン顔は独特で、現代のマンガ顔負け。仙厓さんの解き放たれた自由自在な画境をしめす大作です。

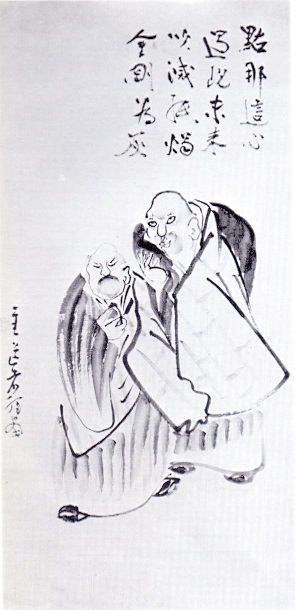

Nansen Fugen (Ō rōshi) 南泉普願 Nanquan Puyuan (王老師 Wang laoshi) (748-835)

|

|

|

Nansen Cuts the Kitten

Cut! Cut!

It is not only the kitten

But the two head monks as well

And even Old Master Wo!

Respectfully painted by Bon Sengai

Jōshū Jūshin 趙州從諗 Zhaozhou Congshen (778–897)

|

|

|

Tanka Tennen 丹霞天然 Danxia Tianran (739-824)

|

Notes: This brush painting by Sengai is about the story of the Chan monk 天然 Tianran (739-824), a disciple of 石頭 Shitou. One frigid cold winter evening Tianran was staying at a temple in Changan. Chattering with cold he took one of the wooden Buddha images from the altar and burned it in the stove to warm his backside. When the temple director saw this he was shocked and exclaimed,

|

|

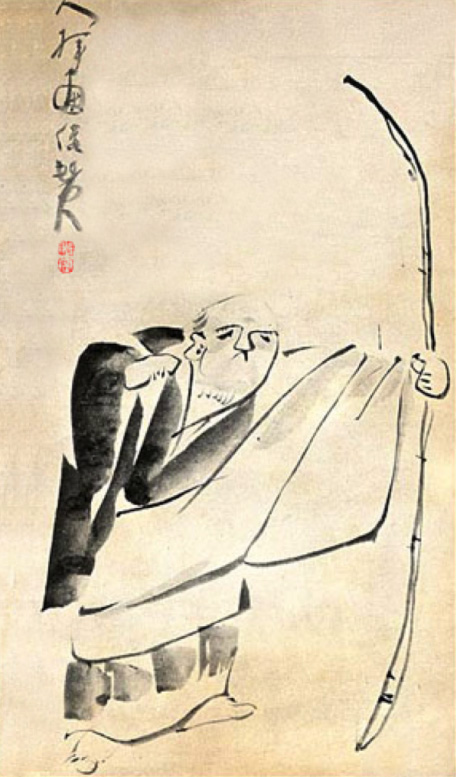

石鞏慧藏 Shigong Huizang (n. d.)

(Rōmaji:) Sekkyō/Shakkyō Ezō

"Shigong and the Bow" by 仙厓義梵 Sengai Gibon

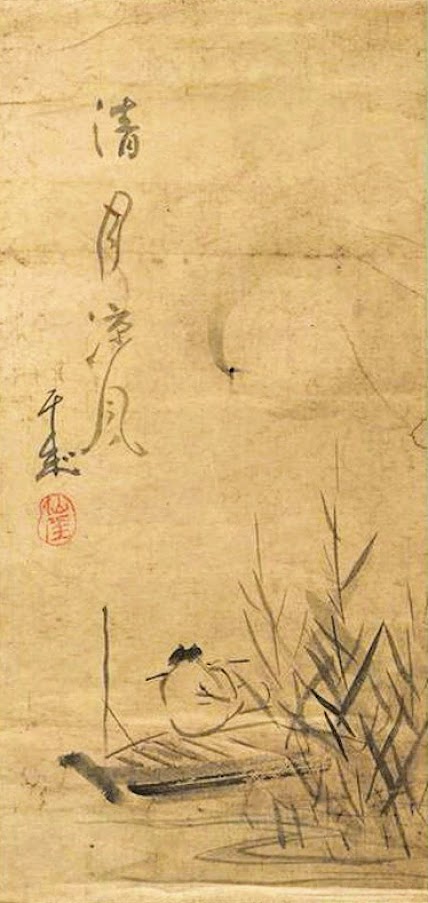

Sensu Kassan 船子夾山

|

|

|

Kensu oshō (蜆子 和尚 Xianzi heshang)

|

【絵画データ】

|

|

Suibi Mugaku 翠微無學 Cuiwei Wuxue (9th c.)

|

|

Ryōtan Sūshin

龍潭崇信 Longtan Chongxin (9th cent.)

& Tokusan Senkan 德山宣鑑 Deshan Xuanjian (780/2-865)

Lung-t'an and Te-shan (Wumenguan, Case 28) |

|

Kyōgen Chikan 香嚴智閑 Xiangyan Zhixian (?-898)

Hsiang-yen Sweeps the Grounds (Wumenguan, Case 5) |

|

明菴栄西 Myōan Eisai (1141-1215)

明菴栄西 Myōan Eisai (1141-1215) 『栄西禅師図』 作者:仙 厓 【絵画データ】 |

|

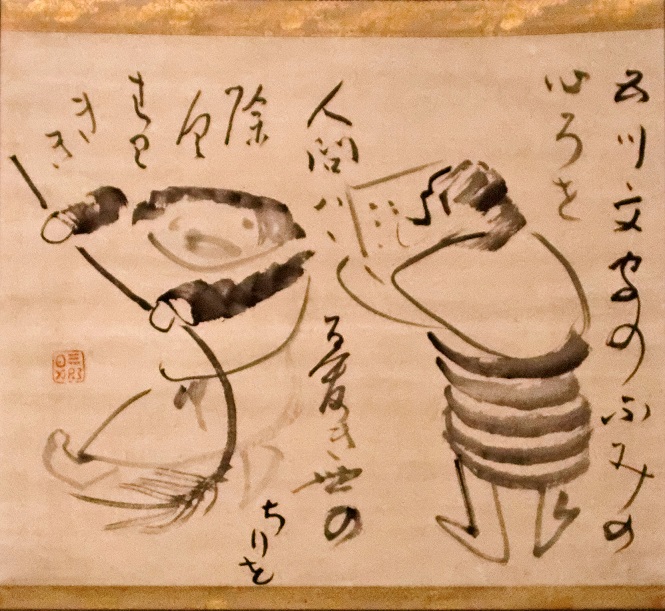

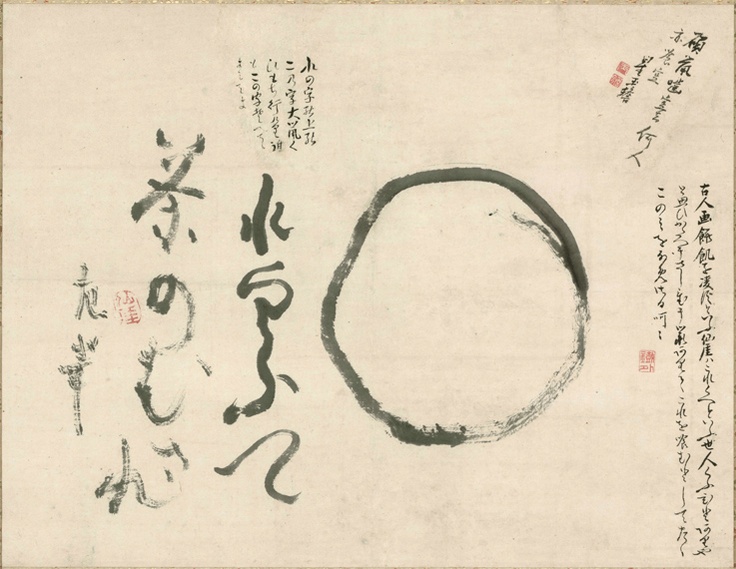

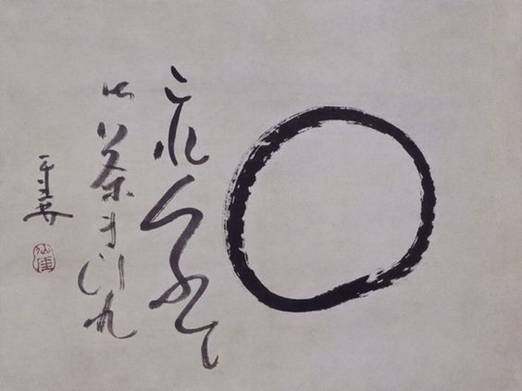

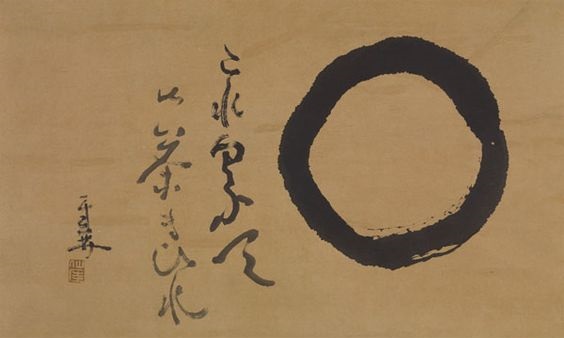

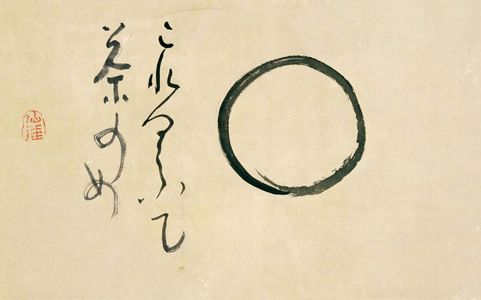

円相図 Ensō | The Circle

「これくふて御茶まひれ」

「これでも食べて、お茶でも飲みなさい」

これを食うて茶でも飲めと勧める

これくふて 茶のめ

Eat this and have a cup of tea

Ox and boy

Signed and sealed Sengai

Hanging scroll; ink and slight color on paper

33.7 x 54.2cm.

The poem reads: Tsune no michi fumimayouna to oborozuki (In the moonlight haze, follow the familiar path--or you might get lost)

The Grand Sengai Exhibition — Spirit of Zen Assembled

Idemitsu Museum of Arts, Tokyo

October 1 - November 13, 2016

Edo period Zen priest Sengai (1750-1837) is known for disseminating the teachings of Zen through laughter and humor. The paintings and calligraphy of Sengai, besides the collection of Shōfuku-ji in Hakata of which he was the head priest and of Kyohaku-in where he spent his retired life, the Idemitsu collection assembled by Idemitsu Sazo the first director of the Museum, the Fukuoka Museum collection and the Kyushu University, School of Letters collection (Former Collection of Dr. Morihiko Nakayama) are considered to be outstanding both in quality and quantity. These extraordinary collections of the eastern and the western Japan will meet for the first time since the exhibition held in 1986 (Shōwa 61) to commemorate Sengai´s 150th year memorial. This exhibition will present a chance to explore the world of Zen painting and to feel the spirit of Zen preached by Priest Sengai.

Sengai's Dharma lineage

[…]

南浦紹明 Nampo Jōmyō (1235-1308) [大應國師 Daiō Kokushi]

宗峰妙超 Shūhō Myōchō (1282-1337) [大燈國師 Daitō Kokushi

關山慧玄 Kanzan Egen (1277-1360) [無相大師 Musō Daishi]

授翁宗弼 Juō Sōhitsu (1296-1380)

無因宗因 Muin Sōin (1326-1410)

日峰宗舜 Nippō Shōshun (1367-1448)

義天玄詔 Giten Genshō

雪江宗深 Sekkō Sōshin (1408-1486)

特芳禪傑 Tokuhō Zenketsu (1419-1506)

大休宗休 Daikyū Sōkyū (1468-1549)

太原崇孚 Taigen Sūfu (1495-1555)

東谷宗杲 Tōkoku Sōkō

鐵山宗鈍 Tetsusan Sōdon

大室祖丘 Daishitsu Sokyū

心嶽玄精 Shingan Genshō

鼇峰道哲 Gōhō Dōtetsu

節巖道 圓 Setsugan Dō'en (1607-1675)

賢巖禪悅 Kengan Zen'etsu (1618-1696)

古月禪材 Kogetsu Zenzai (1667-1751)

月船禪慧 Gessen Zen'e (1702-1781)

仙崖義梵 Sengai Gibbon (1750-1837)

SENGAI GIBON

Richard Bryan McDaniel: Zen Masters of Japan. The Second Step East. Rutland, Vermont: Tuttle Publishing, 2013.

Sengai Gibon's parents were farmers, and throughout his life he retained a deep respect for agricultural workers. “Farmers,” he wrote, “are the foundation of civilization.” He became a monk at age eleven, primarily in order to reduce the financial burden on his family. At the temple school he attended, he was introduced not only to Buddhist doctrine and practice, but also to calligraphy, brushwork, and poetic composition. Even as a youngster, Sengai demonstrated a talent for drawing.

At the age of nineteen, he decided to look for a teacher who could help him achieve awakening. He traveled about Japan, visiting temple after temple, seeking an appropriate master, finally settling upon Gessen Zenne, under whose direction Gasan Jito and Inzan Ien had come to their first kensho.

Gessen assigned Sengai the koan based on a problem Kyogen Chikan put to his disciples [Xiangyan Zhixian; cf. Zen Masters of China, Chapter 14]:

“Imagine that a man has climbed high into a tree then falls. Before he hits the ground, he is able to grab a branch between his teeth. There he hangs, his hands unable to grasp anything, his feet dangling. A sincere inquirer comes by and asks him, ‘Why did the First Patriarch come east?' If he speaks, he'll fall and die. If he doesn't speak, he fails in compassion by not responding to the question. If you were in his circumstances, what would you do?”

When Sengai resolved the koan, he followed the traditional practice of expressing his understanding in verse:

Old Shakyamuni has been dead some 2000 years

Maitreya Buddha will not be born for eons to come

Sentient beings find this difficult to comprehend

But this is the way it is: the nostrils above the lips

Sengai remained with Gessen for another thirteen years, until the master's death in 1781, then he completed koan study with Gessen's successor, Seisetsu Shucho. After that, he undertook a second pilgrimage of Zen temples before eventually accepting the position of abbot at Shofukuji, the temple founded at Hakata by Myoan Eisai in 1195. There he acquired a reputation for his prowess as a spiritual director and for his personal modesty. He eschewed the formal trappings of office and limited his meals to what he acquired through the daily round of takuhatsu. He refused to accept Imperial Honors until it would have been impolitic to continue to do so. When he did finally agree to receive the purple robe, the sign of the highest rank a priest could achieve, he did not attend the investiture ceremony himself but sent a proxy. He used the funds intended for the celebration of his promotion on temple repairs

At the age of 61, he appointed his primary Dharma Heir, Tangen Toi, abbot in his stead and he retired to a small hermitage he called Kyohakuin—“The Empty White House.”

Freed from the responsibilities of an abbot of a major Zen Temple, Sengai looked forward to a time of solitude and described his new life in a number of poems:

Buddha had 80,000 monks

Confucius 3000 disciples.

I sit alone on a vine-covered stone

Watching the occasional cloud go by.This verse accompanies a drawing of Kyohakuin:

I came alone

I will die alone

In between

I remain alone night and day.The I who came thus

The I who will pass away thus

Is the same I living

In this small hut all alone.These poems, however, may have described more an idealistic than an actual state, because, as it turned out, in some ways Sengai's career began after his retirement.

Once he retired to Kyohakuin, he dedicated himself to art. While he had had no professional training other than that which all Rin zai students acquired, he had a prodigious talent, and his work quickly gained admirers. He made use of the same monochromatic sumi-e form that had been used by many Zen-influenced artists, including Hakuin. Sengai's works often consisted of only a few quick brush strokes, at times accompanying a poem or other work of calligraphy, but the almost nonchalant images he composed in this manner were full of vigor and humor. One of his most reproduced paintings consists only of a circle, a triangle, and a square—the three most basic geometrical forms. (See the illustration on page 60; Japanese script is read from right to left, so the image appears reversed to western viewers who see the square, rather than the circle, at the beginning of the sequence). Unlike Ikkyu, Sengai was scrupulous about keeping the precepts and generally led an exemplary life, but at times his humor was as racy as Ikkyu's—as in a painting of a priest's penis with the inscription, “An unused treasure.”

Almost anything he saw inspired him. His subjects included landscapes, people engaged in the most mundane activities (such as measuring salt), household implements, animals, and sea life; he drew men working in the fields, their crops, and the tools they used; he made pictures of flowers, bamboo, and reeds. He also, of course, returned over and over to Buddhist themes, including several light-hearted portraits of Bodhidharma, one of which included the inscription: “Nine years seated before a wall—how boring!” He did a number of paintings based on Basho's koan about the old pond and the frog, including some parodies:

「古池や芭蕉飛こむ水の音」

「古池や 芭蕉飛び込む 水の音」An old pond

Basho jumps in

Water sound!What Sengai demonstrated in his art, what continues to make his pieces so attractive, is the natural playfulness that follows from the Zen experience of awakening. In spite of the rigorous training associated with the practice, it results in a joyous and irreverent sense of being at home in the world. Sengai caught that feeling nicely in his painting of Tanka Tennen [Tanxia Tianran, cf. Zen Masters of China, Chapter Six] warming his buttocks on the fire he had made by burning a wooden Buddha.

In spite of his longing for solitude, Sengai found himself besieged with visitors after his retirement. His personal friends included poets, tea-masters, artists, musicians, as well as local merchants, craftspeople, and medical practitioners. There was also a local drunk, Icimaru Iwane, whose caricature Sengai drew bringing him a pot of turnips, “to try to trick me into doing a drawing for him.”

Some of his visitors came for spiritual guidance, but many, like Icimaru, came to ask for one of his calligraphies or a drawing. People brought bits of paper, hoping he would write a few words or make a quick sketch, prompting his remark that perhaps they mistook Kyohakuin for a privy. This stream of visitors could be exhausting, and on one occasion, Sengai stuck his head out his window and shouted, “The abbot is away today! Please come back another time!”

When Sengai was first appointed Abbot of Shofukuji, he discovered that some of the monks were in the habit of sneaking out of the monastery at night in order to spend time in bars and brothels. One monk in particular made regular forays in this manner.

Sengai found the small wooden platform the monk had been placed against the wall to assist him in leaving and returning to the temple grounds. One night, when he knew the monk was engaged on another of these excursions, Sengai removed the platform and waited by the wall. On his return home the monk mounted the wall and extended his foot towards the platform. He stepped instead into the cupped hands of the abbot. Sengai carefully helped him down, then, without a word of admonition, told the monk, “It's a very damp morning; please take care not to catch cold.”

The platform was never replaced, and monks no longer snuck out of the monastery at night.

After achieving his initial kensho, Tangen Toi asked Sengai permission to undertake the traditional pilgrimage to other temples to deepen his understanding. But each time he put in his request, Sengai wordlessly gave him a rap on the head with his abbot's stick. After being refused in this way several times, Tangen approached the head monk and asked if he would intervene on his behalf. The head monk agreed to do so and spoke to Sengai who relented and agreed to allow Tangen to begin his journey. However, when Tangen presented himself to thank his teacher, once more Sengai struck him and said nothing.

Tangen sought out the head monk and complained, “I thought you'd said that the master had agreed to allow me to go on pilgrimage. And yet when I saw him just now, once again all he did was strike me. Has he changed his mind?”

The head monk went in to Sengai and asked about the matter.

“Of course Tangen is free to go,” Sengai said. “But when he returns he'll be fully awakened, and I won't have any further reason to strike him. I just wanted to take advantage of this last opportunity.”

During a New Year's celebration, a group of villagers came to Sengai and asked him to write something in calligraphy that they could hang in their local temple to promote prosperity throughout the coming year. Sengai wrote three lines:

Parents die

Children die

Grandchildren die“But this is horrible!” the villagers complained.

“Not at all,” Sengai told them. “What would be horrible were if things occurred in the other order—if children died before their parents. There's no greater example of good fortune than that things should proceed in their appointed order.”

A certain daimyo was so proud of the chrysanthemums growing on his estate that members of his household came to feel he cared more for his flowers than he did for them. When one of his retainers inadvertently broke one of these flowers from its stalk, the daimyo flew into a rage and had the man put under restraint. The retainer, in turn, considered that he had no option but to commit seppuku.

One of the retainer's family members sought out Sengai and asked if there were any way he could intervene on behalf of the imprisoned man. Sengai agreed to see what he could do.

That evening the daimyo heard a commotion in the garden. Rushing out, he found the famous and respected Zen master cutting the blossoms off each of his chrysanthemum stalks. “What's the meaning of this?” the lord demanded.

“Even the most beautiful weeds become rank if they aren't properly pruned,” Sengai told him.

The daimyo released his retainer and no longer gave his flowers more consideration than they were due.

Sengai was proud of Shokfukuji's status as a leading Zen temple in Japan, and felt that he left it in good hands when Tangen became abbot. He was happy that Tangen had the opportunity to oversee the temple's 600th Anniversary Celebrations. But, in 1836, Tangen fell afoul of the local authorities and was banished to Oshi ma Island, and, at age 86, Sengai had to come out of retirement and resume his duties at Shofukuji.

He lived for two more years, attaining the beiju—his 88th year, which is considered to be the age of congratulations. He might have lived longer had he not been burdened by the administrative duties of his office. As it was, he fell ill a few weeks after his birthday celebration.

When Sengai was on his deathbed, many of his disciples gathered about to spend his last moments with him. He looked around at them and said, “I don't want to die.”

The students considered what he meant by these words, what final message their master intended them to understand. Sengai listened to the discussion for a few moments, then shouted: “No! Really! I don't want to die!”

His death poem was:

One who knows the where and when of coming

One who knows the where and when of departing

No longer clinging to the cliff

Clouds never know where the breeze will carry them

Sengai: Master Zen Painter

by 古田紹欽 Furuta Shōkin (1911-2001)

... we now turn to Sengai as a unique individual who had become awakened to primary enlightenment and who could represent that experience in visual form. Whether or not such an experience could be depicted might be argued, but this problem is not relevant to Sengai. His experience of enlightenment quite naturally took a visual form, expressing itself directly in his drawings and calligraphy. To put it in another way, there is no artificiality in his work; rather it is a direct expression of the experience of enlightenment itself.

Sengai's gift for drawing and calligraphy was superior to even that of professional painters and calligraphers. Such gifted people often end up defeated by their own talent--drowned in it, so to speak. There have been many who, though recognized as geniuses, never achieved success, due to misfortune brought on by their own talent. They would not have been brought to ruin if they had not been so gifted.

We know a number of Zen personalities who were gifted in either drawing or calligraphy, particularly those who had exceptional talent for drawing, but whose genius was often the cause of their undoing as Zen practitioners. It is only when it is unified with Zen in their art that their talent truly shines. Talent alone produces a mere painter whose work totally lacks what is unique to the art of Zen practitioners. Zen painters, by definition, must have Zen in their art. The same can be said of calligraphy. There have been several instances in which Zen practitioners failed to see this obvious point and allowed themselves to "drown" in their talent, eventually turning out to be nothing more than ordinary painters or calligraphers.

Sengai does not belong to this type: blessed with superior gifts, he depicts Zen in his drawings and calligraphy. Zen, of course, is formless, figureless, and bodiless, but nevertheless Sengai manages to reveal it. His pictures, unconventional and funny, might be classified as cartoons, and yet they possess a certain distinguishing severity. Zen is there, and so is enlightenment. Moreover, it all seems to be done so effortlessly. Enlightenment is there, but it is enlightenment without pretense. "A scholar smacking of a pedant might still be bearable," Sengai wrote, as mentioned earlier, over a drawing entitled "Great Master Bodhidharma," "while a buddha with a buddha air is not bearable." For Sengai, both sanctimonious Buddhism and self-congratulatory enlightenment were things to avoid.

ZEN ANECDOTES

Translated by Lucien Stryk (1924-2013) & Takashi Ikemoto [池本喬 1906-1980]

In: ZEN: Poems, Prayers, Sermons, Anecdotes, Interviews

Anchor Books, Doubleday & Co., Inc., Garden City, New York, 1963, pp. 108-109.

7

There was to be a big party at the house of the Chief Minister of the Kuroda Clan of Hakata, and both Kamei Shoyo, the famous Confucian scholar, and the master Sengai (1750-1837, Rinzai) were invited. The host informed Sengai that the great teacher would be present, implying that the master, who was indifferent to worldly matters, would have to come dressed for the occasion.

On the appointed day Sengai entered the mansion wearing a costume of white, violet, and gold. His rosary was of amethyst and he even carried a ceremony-fan. Followed by his disciples, he crossed the room in great dignity.

Of course, the sight of Sengafs getup was hateful to Shoyo, and he couldn't restrain himself from calling out, “Master, why did you come dressed as a fine lady?”

At this the other guests held their breath.

Sengai smiled and, moving straight up to Shoyo, whacked him on the head with his fan, and said, “Why, it was to give birth to this fine gentleman.”

8

A wealthy man invited Sengai to a housewarming and, after serving him a fine meal, asked him to write a poem in honor of the occasion. Sengai quickly wrote down the first half of a waka, which made the host, who had been hovering over his shoulder, extremely angry. It read:

The house is surrounded

By the gods of poverty.

Ignoring the host and the guests, who on being informed of what he had written looked daggers at him, Sengai smoked his pipe in silence. Suddenly he grasped his brush and completed the poem with these lines:

How can the deities of good luck

Ever leave it?

When the host and the guests read these lines there was great rejoicing, and all praised Sengai warmly.

仙厓義梵 SENGAI GIBON

In: Yoel Hoffmann: Japanese Death Poems: Written by Zen Monks and Haiku Poets on the Verge of Death. Tuttle Publishing. 1986.

Died on the seventh day of the tenth month, 1837 at the age of eighty-eight

He who comes knows only his coming

He who goes knows only his end.

To be saved from the chasm

Why cling to the cliff?

Clouds floating low

Never know where the breezes will blow them.

Sengai is one of the most colorful figures in Japanese history-- a Zen monk, a painter, and a poet. His drawings and writings, both done with a flourish, vibrate with Zen insight and humor.

Sengai gives one to understand, in many of his poems and sketches, that a "lifeless" life is not worth living. He once presented to a newlywed a marriage present, a senryu written in her honor and urging her thus:

Young bride

Be alive till they say to you

Die! Die!

In one of his sketches, a bent and bald old man is vying to outwit death. Above the picture Sengai wrote:

If you say, "Come back later,"

He will speedily come to snatch you away.

Say rather, "I shall not be in till I'm ninety-nine."

Sengai's Portrait & Sengai's Nirvana

by his friend Saitō Shūho 斎藤秋圃 (1769-1861)

![]()

Sengai Gibon

Meghalt 1837-ben a tizedik hónap 7. napján. 88 évesen.

Vers a halál mesgyéjéről

Fordította: Somogyvári Zsolt

Jisei, Farkas Lőrinc Imre Kiadó, 1994, 26. oldal

A fordítás alapjául szolgáló mű:

Yoel Hoffmann: Japanese Death Poems: Written by Zen Monks and Haiku Poets on the Verge of Death. Tuttle Publishing. 1986.

Ő, aki jön, csak a kezdetét ismeri

Ő, aki megy, csak a végét.

Megmentve a szakadéktól

Miért e sziklába kapaszkodás?

A felhők alacsonyan szállnak

Sosem tudva, merre fújják őket a szelek.