ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

Maitreyi/deLancey Kapleau

born Joan Delancey Robinson (December 9, 1922 – July 22, 2010)

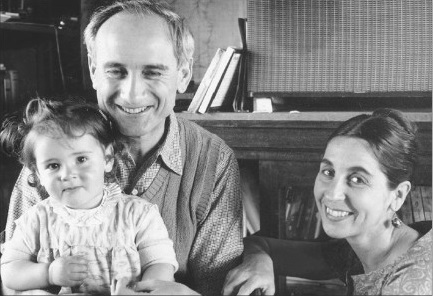

Philip Kapleau, his wife deLancey with their daughter Sudarshana in Kamakura, 1962

*Cf. Philip Kapleau: "My debt to my wife, deLancey, is no small one. At all stages of the writing she has encouraged and worked with me. Indeed, for several years these labors constituted her major practice of zazen." In: The Three Pillars of Zen (PDF). More in the Chapter: Enlightenment Experience, Mrs. D. K., A Canadian Housewife, Age 35.

The text below is by Phil H. Grant, the author of Cabeza and the Meaning of Wilderness: An Exploration of Nature, and Mind

https://www.wildernessofmindzc.org/sex-and-the-jealous-zen-master/If you read Philip Kapleau's and deLancey's enlightenment experiences in The Three Pillars there is a dramatic difference. His is dry, almost cold: He worked like crazy on his koan, Yasutani Roshi admired how ardent he was, until “the moon of truth” rose within his mind. DeLancey was working with Yasutani Roshi also (which was how she met Kapleau, and married him before her experience) but hers was one of the most beautiful, and human, in the whole book. At sesshin Yasutani had been talking about the “enemy” (delusion). She immediately visualized the “enemy” and in utter joy “rushed” to throw her rounds around “him.” All sense of an individual self fell away and she “grew dizzy with delight.” She truly, at that moment, had swallowed all the waters of the West River. And it was at a later time at home in her garden, after listening to the “Song of Thanksgiving” that another deeper opening occurred. The final page is perhaps my favorite of the entire book. “The least weather variation . . . touches me as a, how can I say, miracle of unmatched wonder, beauty and goodness. I can hear a ‘song' coming forth from everything . . . they intermingled in one inexpressibly vast unity. I feel a love without object . . . best called lovingness.” And though I highly doubt that she'd read of Einstein's absolute space-time or quantum probabilities, her description of a “network of causes and effects reaching forward and back, of “Time-Existence,” of an “infinity of Silence and Voidness,” yet “no place . . . where one object does not flow into another,” sure sounds to me like she had a direct experience of them both. Interesting. To say the least. She helped edit The Three Pillars but it seems after they came to America she left him and Zen.

Mrs. deLancey Kapleau at Sri Ramanasramam, Tiruvannamalai. The Mountain Path, 1967, Vol. IV. No. 4. pp. 336-338.

Enlightenment Experience, Mrs. D. K., A Canadian Housewife, Age 35

This is one of eight contemporary enlightenment experiences of Japanese and Westerners, from the book: The Three Pillars of Zen, by Philip Kapleau

"Canada and the United States

The early years of my life were quiet and uneventful. No tragedy touched me, and my parents were devoted to the bringing up of myself and my two sisters. It could almost be called an ideal childhood by most Western standards. Even from the first, though, there were recurrent periods of despair and loneliness which used to seep up from no apparent source, overflowing into streams of tears and engulfing me to the exclusion of everything else. At these times the painful feeling of being entrapped was overpowering, and simply to be a human being a wretched and ignominious lot.

Once in my early teens I was lent some books of Hindu stories which provoked my intensest interest. They spoke unabashedly of a multiplicity of lives and of the soul's freedom, of man's spiritual self and the possibility of life without a physical body. Most of the details of this reading evaporated in the face of something stirring much deeper in my being and I felt happy to learn that such understanding did exist. The Indian myths of limitless time touched my deepest concerns, and I vowed that one day I would visit India for myself.

After my enrollment at university I began in earnest to study religious literature, even trying some simple meditation. The years at university taught me the joy and stimulation of intellectual discovery, but they were at the same time pervaded by a mounting restlessness. At length I graduated and commenced graduate studies. Toward the end of that first year my life took an unexpected turn. After a few indecisive months I went to the United States to marry an American whom I had met in Canada.

Within a few months our marriage took place and almost immediately after I awoke to find myself a widow. The violent, self-inflicted death of my husband was a shock more severe than anything I had ever experienced. The circumstances and implications of it precipitated me into the innermost depths of my being, where the foundations shook with a truly terrifying intensity. I could not divest myself of a deep sense of human responsibility for it. Perception, maturity, wisdom - all these I sorely lacked.

Frequently at this time I would be seized by a total numbness, and always there was fear, a deep pervasive fear, which lasted long, obstructing my breathing and inhibiting my eating. Often at night I would find myself seated cross-legged on the floor, rocking back and forth and hitting my head against the tiles, almost delirious with grief and despair.

One afternoon, returning from an errand and stepping into my apartment, where I lived alone, the profoundest misery seized me and in helplessness I slumped to the floor. "I am dying." I sobbed, "I have killed all my gods. I have no key to resurrection. I am totally alone." Stark fear and utter despair possessed me, and I lay on the floor for I don't know how long until from the pit of my abdomen a cry came forth: "If there is any being in the entire universe who cares whether I live or die, help me, oh help me!"

Gradually an idea took form and I began to write. I had a very dear friend who had recently renounced the world. She was now living in an ashram1 in South India, and I begged her to direct her meditations toward me, for I needed help badly and no longer felt capable of helping myself. Quickly she replied that she and others in the ashram were sending as much spiritual support as they could. Her response so touched me that I decided to leave the West as soon as I could for India.

It was many months more before this was possible. All my energies were now harnessed into winding up my husband's estate and selling my belongings. At last I sailed, exhausted, to India, intending to stay there until I had found an enlightened teacher. Exactly three years had passed since I had come to the United States.

India and Burma

One hot afternoon two months after my departure from New York I entered the compound of the large ashram where my friend was living. Silently I was ushered into her tiny room, and such was my relief when she came to greet me, gentle and smiling, that I fell into a fit of tears, my arms became paralyzed, and I began to faint. Without my fully realizing it, the years in the United States had been so fraught with inner tension and struggle that I could not spontaneously adjust to this tranquility. The tautness of mind and body continued for a long time from force of habit.

The ashram, set on the shores of die Bay of Bengal, was rejuvenating. But metaphysical speculation and philosophical discussion are strong in India and I had always been quick to succumb to them. While part of me was stimulated by them, my deepest instincts warned me that they would in the end prove unavailing. A regimen which encouraged so much study and reading, it seemed to me, was at that particular time the very thing I should not have. I felt a growing need for closely guided meditation.

My mounting dissatisfaction with what I took to be haphazard meditation at the ashram coincided with the visit of an American Buddhist who had practiced Zen in Japan for a number of years. What impressed me most about this American was the serenity with which he mingled with and absorbed himself in all the varied circumstances he encountered in the ashram and his compassionate interest in the lives of all whom he encountered, including my own, so full of desperate and uneven strivings. I determined to go to Japan if I could get his help. This he unstintingly gave, together with the assurance of helping me find a Zen teacher there.

Following my departure from the ashram I traveled up and down India, visiting at other ashrams, exploring archaeological sites, and absorbing the rich lore and pervasive religious atmosphere of Buddhist and Hindu holy places: the shrines, temples, and caves with which India abounds. An overwhelming intensity of spiritual vision informs her architecture and mighty cave sculpture, so that it is impossible to step into these caves without being swept up by this religious fervor. Standing before the giant rock-cut Buddhas, I fairly trembled in awe, and my resolution to follow the Buddha's path was given the most powerful impetus.

I had long hoped to visit Burma, which I had pictured as being second only to Tibet in its unique concern with religion as the foundation of daily life. So when my American friend wrote that of all the Southeast Asian Buddhist countries the meditation centers of Burma were reputed to be the best, suggesting that I join him in the center of a famous Burmese master (Mahasi Sayadaw) in Rangoon for five weeks of intensive meditation, I jumped at the chance.

Now began my first formal practice of meditation under the guidance of a teacher, and in every direction it proved to be extremely painful. The hot season had already settled in when I reached Rangoon, and I early contracted a fever together with a racking cough, both of which lasted almost until I left and considerably debilitated me. In addition to the frightful heat and the lethargy it fostered, there was the unremitting strain of sitting alone in a small bare cubicle on a wooden-plank bed hour after hour struggling against the scaring pains in knees and back from cross-legged sitting. For the beginner, lacking the invisible support of others sitting alongside him, and the more visible support of a varied timetable, as in Zen in Japan, sitting alone is unbearably difficult and one soon finds oneself seeking means of escape from the tedium and pain.

The meditation itself consisted of concentration on the rising and falling of the breath, the attention being focused on the diaphragm. When the mind wandered (which it repeatedly did), it was to be recalled by the words "thinking, thinking, thinking" until it had been re-established in the diaphragm. Every other distraction was similarly treated. "Coughing, coughing" when one coughed, "hearing, hearing" when any sound captured the attention. An hour's sitting alternated with an hour's walking, which was done for the most part at a funereal pace back and forth outside each person's quarters in perfect silence. The hands were held behind the back and the mind was concentrated on noting only the movements of each step. "Lifting, lifting" when the foot was raised, "moving" when it was carried forward, "putting" when it was placed on the ground.

Each day at noon we met with our preceptor, a senior monk, who examined us on our progress. He asked minute questions and called for detailed accounts of sitting time. When I complained to him that my frequent mental wanderings were due to boredom, he laughed and told me to think "bored, bored, bored" until the boredom vanished. To my surprise this worked.

Like everyone else, I had to sign a pledge upon entering the center to observe the Buddhist precepts,2 which forbade eating after twelve noon, and to abstain from sleeping more than five hours a night. Food was brought to my door twice before noon in tiffin carriers, and I ate it alone while meditating "lifting lifting, putting putting, chewing chewing, swallowing swallowing." In just this way the tiniest detail of every action, mental as well as physical, had to be attended to with total attention.

Here in the center, for the first time in my life, I was relegated to a position socially below men, and further, as a laywoman devotee, to the lowest stratum of all in a structure which placed monks at the top, nuns next, then laymen, and finally laywomen. Nevertheless, I was enormously grateful for this opportunity to practice meditation even from such a lowly position, and later came to see that it was only my ego which had led me to consider my position in the first place.

At the end of five weeks my concentration and health had improved considerably in spite of, or because of, the acute pain and discomfort which I had of my own free will undertaken. The turning of the mind from outer activity to inner contemplation was by far the most rewarding task I had ever undertaken, and unquestionably the most difficult. The outside world, when I re-entered it, appeared radiantly beautiful to my fresh gaze, and I had a serenity and equanimity which, while not yet deep, surpassed anything I had hitherto experienced. I knew I had taken my first step in the direction I wanted to travel.

Japan and Zen

The very day of my arrival in Japan my American friend conducted me to Ryutaku-ji, a Rinzai monastery perching like a giant bird amidst groves of towering pines and bamboo in the shadow of majestic Mount Fuji and looking down upon a rolling valley of breath-taking beauty. Through the generosity of its master, Soen-roshi, this was to be my home for the next five months. Under his benevolent guidance I began to learn the structure and discipline of monastery life. Summoned by the gong, I teamed to rise at the unconscionable hour of 4 a.m., to leap into my monastery robes, splash cold water on my face, and take my position with the monks in the main hall in the cold dawn for the early-morning sutra-chanting. The intoning of the sutras became one of the richest experiences of my life and inspired me profoundly.

Slowly my impatient nature began to break down and some measure of equanimity began to establish itself within me. The long hours spent shivering on agonizing knees in a drafty hall awaiting my turn to go before the roshi for sanzen enforced upon me a patience I had not believed myself capable of. The hours of daily zazen, and even more of sesshin, were also painfully learned lessons in patience and endurance, punctuated as they were by the smart whack of the kyosaku across my slumping shoulders. Partly it was this Rinzai method of using the stick from the front in response to a gestured request which conditioned my later acute dislike for the kyosaku when it was administered, as it is in the Soto discipline, suddenly and without warning from behind as one sits facing the wall; and partly it was my Western heritage which had taught me to regard beating as a human indignity.

My decision to marry again took me from this Rinzai monastery and I joined the Soto Zen group to which my husband belonged, at Taihei-ji, in the outskirts of Tokyo, under the direction of Yasutani-roshi. Because almost all the followers of this Zen master are laymen and Iaywomen, the sesshin is less rigidly scheduled than in a monastery in order to allow them to attend as much of it as their jobs permit. Consequently, there is much coming and going, which in the beginning is highly distracting. The outwardly rigorous discipline which monastery life enforces had here to he assumed by each individual for himself. I soon perceived that beneath the apparently relaxed air of the sesshin was an intense seriousness. The limited quarters of this temple brought me into closer contact with the others and I found I could no longer retire alone to my tiny room to sleep at night, but had to content myself with just a mat spread out in a room occupied by many others. Doing zazen in these (for me) straintened circumstances was somewhat of a jolt after the strict but spacious atmosphere of the monastery. After a few sesshin at the temple, however, I came to see that sitting with individuals who, like myself, were neither nuns, monks, nor priests was mutually stimulating and inspiring.

The rohatsu sesshin at Taihei-ji was approaching and my feelings toward attending were mixed. I had heard several reports of this yearly mid-winter sesshin from people who had experienced it in monasteries. It was known to be the most arduous of the whole year, a constant battle against cold and fatigue, I had a deep fear of extreme cold. My body would become so tense from shivering that I could not keep my sitting position. And under great fatigue I would become almost lightheaded. These two I regarded as my real foes. At the same time the fact that it marked the enlightenment of the Buddha, which event fell just one day before my own birthday, moved me deeply. At length I determined to go and to put forth my every energy. This was my sixth sesshin in Japan. For the first time I had the firm conviction that it was entirely possible for me to realize my Self at this forthcoming sesshin. I also felt that I sorely needed it. For many weeks there had been a return of the old restlessness and anxiety which I had fought so hard while in the United States. This was now mixed with impatience and irritability. Added to this, I was sick to death of the inner mental and emotional surgings which had hitherto played such a dominant role in my life, and now felt that only through the experience of Self-realization could I cut my way out of this malaise.

I packed my warmest clothes, and as I turned the key in the lock a feeling of deep happiness crept over me. In my heart of hearts I knew that the person who would unlock this door after sesshin would not be the same as the one who was now locking it.

All the first day of the sesshin I found it virtually impossible to keep my mind steady. The comings and goings of the other participants, as well as the noise and confusion occasioned by the use of the kyosaku, were a source of constant interference. When I complained to the roshi how much better my zazen had been alone in my own home, he instructed me to pay no attention to the others, and pointed out how important it was to learn to meditate in distracting circumstances. At no time during the sesshin, however, was I hit with the kyosaku. I had found it so distracting at a previous sesshin that the roshi had given instructions it was not to be used on me.

By the end of the second day my concentration had grown steadier. I no longer had great pain in my legs, and the cold was bearable with all the clothing I had brought. There was, however, a problem which for me took on more and more significance, I had been told repeatedly to put my mind in the pit of my abdomen, or more exactly, in the region below the navel. The more I tried to do this, the less I understood what it was about the bottom of the abdomen which made this spot so significant. It had been called by the roshi a center, or focus, but for me this was meaningful only in a philosophical way. Now I was to put my mind in this "philosophical" spot and to keep repeating "Mu." I could find no relation between any of the organs of the abdomen and the process of Zen meditation, much less enlightenment. The roshi, it is true, had assigned me the Koan Mu after satisfying himself of my earnest desire for Self-realization, and had instructed me as to its purpose and use; nevertheless, I was still perplexed about how to say Mu. Earlier I had tried considering it the same as the Indian mantra Om, endeavoring to be one with its vibration, and without questioning what Mu was. Now I began to conceive of Mu as the diamond at the end of a drill and of myself as a driller working through layers of the mind, which I pictured as geological strata, and through which I was eventually to emerge into something I knew not what.

On the morning of the third day I was truly concentrating, guided by the drilling analogy. I could now focus my mind somewhere in my abdomen without, however, knowing just wbere, and there was growing a rocklike stability to my sitting. By mid-morning, just after the roshi's lecture, I settled into a fairly deep concentration, increasing the force of each breath, which had been synchronized with the repetition of Mu. I expected this increase of effort to strengthen the concentration even further. After some fifteen minutes the combination of this forceful breathing and the repetition of Mu began to produce a strange tingling in my wrists, which spread slowly downward to the hands and fingers as well as upward to the elbows. When this sensation had gotten well under way, I recognized it as identical to what I had experienced under severe emotional shock on several occasions of my life, I told myself that if I increased even further the force of my breathing and concentration, I might come to kensho. I did this and succeeded only in worsening the situation, finally reaching a fainting state. Just before this state erupted I began to feel the most profound and agonizing sorrow, with which came violent shivering spasms and a gnashing of my teeth. Nervous paroxysms shook my body again and again, I wept bitterly and writhed as though a torrent of electricity were surging through me. Then I began to perspire profusely, I felt that the sorrows of the entire universe were tearing at my abdomen and that I was being sucked into a vortex of unbearable agonies. Sometime afterward - I can't say how long - I remember my husband ordering me to stop zazen and to lie down and rest. 1 collapsed onto my sitting cushion and began to shiver. My hands were now quite stiff; neither my fingers, sticking out at odd angles, nor my elbows would bend. My head whirred and I lay exhausted. Slowly the nerves relaxed. In half an hour all had subsided, my energies had returned, and in all respects I was ready to resume zazen.

At the afternoon dokusan the roshi immediately asked what had happened. When I told him he said it was a makyo and to keep on doing zazen. Such things could happen from now on, he warned; they showed my meditation was deepening. He then instructed me to search for Mu in the region of the solar plexus. With the words "solar plexus" suddenly everything fell into position for the first time - I knew exactly where I was going and what I was to do.

The next morning, the fourth day, I awakened with the bell at 4 a.m. and found that I had not separated myself from Mu even while asleep, which was what the roshi had continually urged. During the first sitting period, before morning dokusan, the previous day's symptoms began to appear. This time, telling myself it was only a makyo, I kept right on, determined to "ride it out." Gradually, however, the paralysis descended into my legs as well, and I could just hear my husband say in the distance somewhere that I was in a trance. I thought my body might begin to levitate, but still I kept on with my zazen. Then I fell over helpless and lay still. By the time I felt well enough to resume, morning dokusan was over.

I began to consider that I must be doing something wrong, misdirecting my energy in some way. During the rest period after the morning lecture I suddenly realized that this center where I was being told to put my mind could only be a certain region long familiar to me. From early childhood it was the realm to which I had always retired inwardly in order to reflect. I had built up a whole set of intimate images about it. If ever I wanted to understand the "truth" of a situation, it was to this particular area that I must go to consider such problems, which had to be approached in a childlike frame of mind, free from prejudices. I would simply hold my mind there and be still, almost without breathing, until something coalesced. This I believed was the region the roshi intended. Intuitively I divined it, and with all my energy centered Mu there. In perhaps half an hour a warm spot began to grow in my abdomen, slowly spreading to my spine, and gradually creeping up the spinal column. This was what I had been striving for.

Highly elated, at the next dokusan I told the roshi that I had found the spot and described its functioning to him as I had always experienced it. "Good!" he exclaimed. "Now go on!" Returning to my place, I threw myself into zazen with such vigor that before long the paralysis began to manifest itself again - the severest attack yet. I could not move at all and my husband had to help me lie down, covering me with blankets. While lying there recuperating I thought: My body is obviously unable to stand up to the strain I am putting on it. If I am to see into Mu it must be done with my mind alone and I must somehow restrain the physical and nervous energies, which will have to be conserved for the final effort.

This time when I recovered I tried to concentrate my mind without voicing or thinking Mu, but found it difficult. In practice it meant actually divorcing concentration from breathing rhythm. However, after repeated efforts I did accomplish it and was able to hold my mind steady in my abdomen, as though staring intently at something, and just let my breathing take any rhythm it inclined to. The more I concentrated with my mind in my abdomen, the more thoughts, like clouds, arose. But they were not discursive. They were like steppingstones directing me. I Jumped from one to the next. Constantly moving along a well-defined path which my own intuition bade me follow. Even so, I believed that at some point they must disappear and my mind become quite empty, as I had been led to expect, before kensho. The presence of these thoughts signaled to me that I must still be far from my goal.

In order to conserve as much energy as possible, I relaxed my posture and, to warm myself, pulled die blanket, which had been loose around my body, up over my head. ! let my hands fall limply into my lap and unlocked my legs to a loose cross-legged position. Even that small amount of energy placed at the disposal of my mind increased its concentrative intensity.

The following morning at dokusan, the fifth day, die roshi told me I was at a critical stage and not to separate myself from Mu for a single instant. Fearing that the two remaining days and one night might not be sufficient time, I clung to Mu like a bulldog with its bone - so tenaciously in fact that bells and other signals became dim and unreaL I could no longer remember what we were supposed to do when signals sounded and had to keep asking my husband what they meant. In order to keep up strength I ate heartily at every meal and took all the rest the sesshin schedule allowed. I felt like a child going on a strange new journey, led step by step by the roshi.

That afternoon, going out for a bath, I walked down the road thinking about Mu. I began to get annoyed. What is this Mu, anyway? I asked. What in the name of heaven can it be? It's ridiculous! I'm sure there is no such thing as Mu. Mu isn't anything! I exclaimed in irritation. As soon as I said it was nothing, I suddenly remembered about the identity of opposities. Of course - Mu is also everything! While bathing I thought: If Mu is everything, so is it the bath water, so is it the soap, so is it the bathers. This insight gave fresh impetus to my sitting when I resumed it.

Each morning at about 4:30 it was the roshi's custom to inspect and address all the sitters. Using the analogy of a battle in which the forces of ignorance and enlightenment were pitted against each other, the roshi urged us to "attack" the "enemy" with greater vigor. Now he was saying: "You've reached the stage of hand-to- hand combat. You may use any means and any weapons!" Abruptly at these words I found myself in a dense jungle breaking through the darkness of the thick foliage, with a great knife swinging at my belt, in search of my "emeny." This image came again and again, and I supposed that with Mu I was somehow to overcome the "enemy" upon whom t was now closing in for the final dispatch.

On the afternoon of the sixth day, in my imagination I was again slashing a path through the jungle, babbling to myself and searching ahead for an opening in the darkness and waiting for the "flood of light" which would mean I was at the end of my trail. Suddenly, with a burst of inner laughter, I realized that the only way to overcome this "enemy" when he appeared was to embrace him. No sooner had I thought this than the "enemy" materialized before me clad in the costume of a Roman centurion, his short sword and shield raised in attack. I rushed to him and in joy flung my arms about him. He melted into nothingness. At that instant I saw the brilliant light appear through the darkness of the jungle. It expanded and expanded. I stood staring at it, and into its center leapt the words "Mu is me!'" I stopped short - even my breathing stopped. Could that be so? Yes, that's it! Mu is me and me is Mu! A veritable tidal wave of joy and relief surged through me.

At the end of the next round of walking I whispered to my husband: "How much am I supposed to understand when I understand Mu?" He looked at me closely and asked: "Do you really understand?" "I want the roshi to test me at the next dokusan," I said. The next dokusan was some five hours away. I was impatient to know whether the roshi would confirm my understanding. In my heart of hearts I was certain I knew what Mu was, and I firmly told myself that if my answer was not accepted I would leave Zen forever. If I was wrong, then Zen was wrong. In spite of my own certainty, however, (since I was still unfamiliar with Zen expression) I felt I might not be able to respond to the roshi's testing in appropriate Zen fashion.

Dokusan finally came and I asked the roshi to test me. I expected him to ask only what Mu was. Instead he asked me: "What is the length of Mu? How old is Mu?" I thought these were typical Zen trick questions and I sat silent and perplexed. The roshi watched me closely, then told me that I must see Mu more clearly, and that in the time remaining I was to do zazen with the greatest possible intensity.

When I returned to my place I threw myself into zazen once more with every shred of strength. Now there were no thoughts - I had exhausted all of them. Hour after hour I sat, sat, and sat, thinking only Mu with all my mind. Gradually the heat again rose in my spine. A hot spot appeared between my eyebrows and began to vibrate intensely - From it clouds of heat rolled down my checks, neck, and shoulders, I believed something must surely happen, at the very least an inner explosion. Nothing did happen except that I experienced recurring visions of myself seated cross-legged on a barren mountainside meditating and trudging doggedly through thronged cities in the scorching sun. At the next dokusan I told the roshi about these visions and sensations. He told me that a good way to bring this vibrating center, now between the eyes, back to the solar plexus was to trace a pathway for it by imagining something like honey, sweet and viscous, trickling downward. He also told me not to concern myself with either these visions or the clouds of heat, both of which were the outcome of the prodigious effort I was making. The important thing was only to concentrate steadily on Mu. After a few attempts I was able once more to re-establish this center in the solar plexus and to continue as he had bidden me.

The following day, the seventh, I went before the roshl at dokusan once more. From the six or seven hours of continuous zazen I was so physically exhausted I could scarcely speak. Imperceptibly my mind had slipped into a stale of unearthly clarity and awareness. I knew, and I knew I knew. Gently he began to question me: "What is the age of God? Give me Mu! Show me Mu at the railway station!" Now my inner vision was completely in focus and I responded without hesitation to all his tests, after which the roshi, my husband, who interpreted, and I all laughed joyfully together, and I exclaimed: "It's all so simple!" Whereupon the roshi told me that henceforth my practice in connection with succeeding koans was to be different. Rather than try to become one with a koan as heretofore with Mu, I was to ask myself profoundly: ''What is the spirit of this koan?" When an answer came to me, I was to hang it on a peg, as it were, and do shikan-taza until my next dokusan provided me the opportunity to demonstrate my understanding of it.

Too stiff and tired to continue sitting, I slipped quietly from the main hall and returned to the bathhouse for a second bath, Never before had the road been so roadlike, the shops such perfect shops, nor the winter sky so unutterably a starry sky. Joy bubbled up like a fresh spring.

The days and weeks that followed were the most deeply happy and serene of my life. There was no such thing as a "problem." Things were either done or not done, but in any case there was neither worry nor consternation. Past relationships to people which had once caused me deep disturbance I now saw with perfect understanding. For the first time in my life I was able to move like the air, in any direction, free at last from the self which had always been such a tormenting bond to me.

Six years later

One spring day as I was working in the garden the air seemed to shiver in a strange way, as though the usual sequence of time had opened into a new dimension, and I became aware that something untoward was about to happen, if not that day, then soon. Hoping to prepare in some way for it, I doubled my regular sittings of zazen and studied Buddhist books late into each night.

A few evenings later, after carefully sifting through the Tibetan Book of the Dead and then taking my bath, I sat in front of a painting of the Buddha and listened quietly by candlelight to the slow movement of Beethoven's A Minor Quartet, a deep expression of man`s self-renunciation, and then went to bed. The next morning, just after breakfast, I suddenly felt as though I were being struck by a bolt of lightning, and I began to tremble. All at once the whole trauma of my difficult birth flashed into my mind. Like a key, this opened dark rooms of secret resentments and hidden fears, which flowed out of me like poisons. Tears gushed out and so weakened me I had to lie down. Yet a deep happiness was there... . Slowly my focus changed: "I'm dead! There`s nothing to call me! There never was a me! It's an allegory, a mental image, a pattern upon which nothing was ever modeled." I grew dizzy with delight. Solid objects appeared as shadows, and everything my eyes fell upon was radiantly beautifuL

These words can only hint at what was vividly revealed to me in the days that followed:

1) The world as apprehended by the senses is the least true (in the sense of complete), the least dynamic (in the sense of the eternal movement}, and the least important in a vast "geometry of existence" of unspeakable profundity, whose rate of vibration, whose intensity and subtlety are beyond verbal description.

2) Words are cumbersome and primitive - almost useless in trying to suggest the true multi-dimensional workings of an indescribably vast complex of dynamic force, to contact which one must abandon one 's normal level of consciousness.

3) The least act, such as eating or scratching an arm, is not at all simple. It is merely a visible moment in a network of causes and effects reaching forward into Unknowingness and back into an infinity of Silence, where individual consciousness cannot even enter, There is truly nothing to know, nothing that can be known.

4) The physical world is an infinity of movement, of Time-Existence. But simultaneously it is an infinity of Silence and Voidness. Each object is thus transparent. Everything has its own special inner character, its own karma or "life in time," but at the same time there is no place where there is emptiness, where one object does not flow into another.

5) The least expression of weather variation, a soft rain or a gentle breeze, touches me as a - what can I say? - miracle of unmatched wonder, beauty and goodness. There is nothing to do: just ro be is a supremely total act.

6) Looking into faces, I see something of the long chain of their past existence, and sometimes something of the future. The past ones recede behind the outer face like ever-finer tissues, yet are at the same time impregnated in it.

7) When I am in solitude I can hear a "song" coming forth from everything. Each and every thing has its own song; even moods, thoughts, and feelings have their finer songs. Yet beneath this variety they intermingle in one inexpressibly vast unity.

8) I feel a love which, without object, is best called lovingness. But my old emotional reactions still coarsely interfere with the expressions of this supremely gentle and effortless lovingness.

9) I feel a consciousness which is neither myself nor not myself, which is protecting or leading me into directions helpful to my proper growth and maturity, and propelling me away from that which is against that growth. It is like a stream into which I have flowed and, joyously, is carrying me beyond myself".

Remembering Maitreyi Kapleau

by Jim MacKinnon

The Tail of the Ox, Vol. 15, Issue 3, December 2010, pp. 5-6.

https://mafiadoc.com/december-2010_59a331e51723dd0e40b1ae8b.html

Last summer, many Zen Centre members attended the funeral of Maitreyi Kapleau a long-time friend of the Centre and the wife of the late Roshi Philip Kapleau.

Maitreyi was one of those amazing people you may have the rare privilege to meet, who exude a sense of true grace and serenity. She was invariably warm and gracious with everyone she met, and left them feeling inspired, refreshed, and, in some sense, really appreciated. There was a quality about her which was, for want of a better word, deeply „spiritual‟. Very rounded, but something more.

Maitreyi was born Joan Delancey Robinson, the middle of three sisters born in Winnipeg, Manitoba. She remembered, as a child, being fascinated by all things Indian and having a sense of a deep connection with that amazing country.

When she attended the University of Toronto as a young adult, to study art and archaeology, Delancey continued her fascination with India, and made friends with students from that country.

In the mid-1950s, a good friend of hers went to India to do peace work, and invited Delancey to visit her at the Sri Aurobindo Ashram in Pondicherry, a small coastal town south of Chennai, in South India.

One day, as they were taking their finished lunch trays to be washed after the Ashram meal, her friend introduced her to a pleasant young American man, visiting the ashram from Japan. After a whirlwind courtship, Delancey joined Philip Kapleau in Japan and they were married at an ancient Zen Temple in Kamakura. Zen practice became a central part of her life, and the young couple actually spent their honeymoon in sesshin.

Part of Delancey's sesshin experience is recounted in the Three Pillars of Zen in the section on “DK, a Canadian housewife.”Delancey and Philip Kapleau‟s daughter, Sudarshana, arrived some months later. While in Kamakura, Philip and Delancey were busy with zen practice and the writing of the book, Three Pillars of Zen. During the course of some ten years in Japan, her daughter attended a Japanese school, becoming proficient in the language. Delancey also acquired some proficiency in Japanese. Sudarshana remembers going with her mother to show such visitors as Sri Chinmoy and Lama Govinda the Daibutsu in Kamakura.

Sensei Kapleau, as he became, returned to North America some years later, his family following a year later. In 1970, Delancey and her daughter moved to Ottawa, where one of her sisters was living. They frequently visited Rochester, where Philip Kapleau was busy developing what was to become the largest Zen Buddhist community in the United States.

Delancey had been a student of Yasutani Roshi, in Kamakura. As it happened, her sister in Ottawa headed a Sri Chinmoy meditation centre there. After meeting Sri Chinmoy on several occasions, Delancey become his student. A few years later, now Maitreyi, she moved to Toronto to start a new Sri Chinmoy Meditation Centre there.

Many older members of the Zen Centre have fond memories of Maitreyi and her daughter visiting the Centre, especially at receptions for Roshi Kapleau on his frequent visits. Maitreyi was a real presence.

Entirely present in the moment, Maitreyi slowly savoured every bite.

In recent years, with her health beginning to fail, a number of Sangha members and friends got to know Maitreyi in a more intimate way, thanks to Sangha member Karen Stenning taking the initiative to help organize a group of regular visitors.One of those who had the privilege of spending time with Maitreyi was my wife, Sue. Sue recalls:

I didn't have the opportunity to visit Maitreyi many times, but she made a big impression on me.

Maitreyi was an invariably gracious lady. Even though she didn't recognize me (and would never recognize me after a number of visits due to short term memory loss), she was always happy to have company. Her trust surprised and amazed me. She would get in the car for an outing without worry about who I was and why I was taking her anywhere. I would say, at Sudarshana's direction, that I was a friend of Sudarshana's, and that seemed to be enough for Maitreyi.

Maitreyi was also entirely present in the moment: if she was eating ice cream or chocolate cake, she would slowly savour every bite. I would be watching the time, concerned about getting Maitreyi back to her residence in time for her dinner, but Maitreyi was enjoying where she was and what she was doing; she was not to be rushed. Her patience and attentiveness was a lesson for me.

Every time we went out, Maitreyi would ask the same questions: Do you paint?

No, I don't, I'm not very good at that kind of thing.Maitreyi: You must paint!! Just pick up some paint and a paintbrush and start! Do you meditate?

No, I don't.

Maitreyi: Oh... Have you been to India?

No, but it's at the top of my list.

Maitreyi: You must go right away. It's magical.

Maitreyi loved nature. This past spring, she and I had a wonderful visit to the cherry blossoms in High Park. We stood amongst them for about 45 minutes. As we turned slowly around in the middle of the trees, enjoying the fact of being surrounded by the blossoms, Maitreyi closed her eyes for a moment, lifted her chin toward the sky and breathed in the moment. “This is positively scrumptious!”

I will never forget her.Even as she suffered from a debilitating illness, Maitreyi retained her characteristic poise and graciousness. It is hard not to imagine that this was at least in part the product of years of spiritual practice. Maitreyi was always up for an outing, and was charming with visitors. She loved the colours and sounds of the Temple Night when she came last spring.

An extraordinary life, and an extraordinary person.

We are all the more fortunate for having had her among us, and were so very grateful to have the opportunity to help send her off on the next stage of her remarkable journey.

![]()

Mrs D. K. (Canadienne, sans profession, 35 ans)

PDF: Les trois piliers du zen, pp. 264-273.

Traduit de l’americain par Claude Elsen

![]()

Frau D. K., kanadische Hausfrau, Alter 35

PDF: Die drei Pfeiler des Zen, PP. 349-367.

Übersetzt aus dem Englischen von Brigitte D'Ortschy

![]()

Experiencia de iluminacion, Sra. D. K., ama de casa canadiense, 35 años de edad

in: Philip Kapleau: Los tres pilares del Zen, pp. 137-143.

![]()

Terebess Gábor találkozott vele Japánban, ezt írja:

Mrs. deLancey Kapleau, akinek megvilágosulás-élménye megtalálható férje bestseller könyvében, A zen három pillérében, "kanadai háziasszony" címszó alatt, azidőben Kamakurában lakott (1364 Nagoe), hogy kislányukat japán iskolába járathassák. Philip Kapleau eközben saját külön zen útját egyengette otthon Amerikában.

1967 őszén egyik ismerőse magával vitt Kapleau feleségéhez látogatóba, hogy néhány tanáccsal egyengesse az utam a zen körül. Amit türelmesen és kedvesen meg is tett.

Vajon mi lett a kislányból? Itt megtalálható: http://www.sudarshana.com/about.html