ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

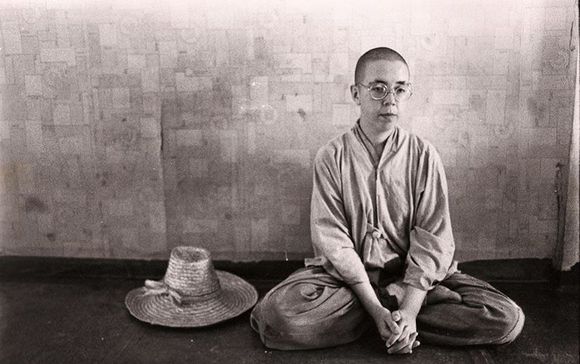

Martine Batchelor (1953-)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Martine_Batchelor

Martine Batchelor was born in France in 1953. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in Korea in 1975. She studied Seon Buddhism under the guidance of the late Master Kusan at Songgwangsa monastery until 1985. Her Seon training also took her to nunneries in Taiwan and Japan. From 1981 she served as Kusan Sunim's interpreter and accompanied him on lecture tours throughout the United States and Europe. She translated his book 'The Way of Korean Zen' and has written an unpublished manuscript about the life of Korean Seon nuns.

She returned to Europe with her husband, Stephen, in 1985. She was a member of the Sharpham North Community in Devon, England for six years. She worked as a lecturer and spiritual counsellor both at Gaia House and elsewhere in Britain. She has also been involved in interfaith dialogue. Until recently she was a Trustee of the International Sacred Literature Trust.

In 1992 she published, as co-editor, 'Buddhism and Ecology'. In 1996 she published, as editor, 'Walking on Lotus Flowers' which in 2001 will be reissued under the title 'A Women's Guide to Buddhism'. She is the author of 'Principles of Zen' and her most recent publication is 'Meditation for Life', an illustrated book on meditation.

With her husband she co-leads meditation retreats worldwide. They now live in France.

She speaks French, English and Korean and can read Chinese characters. She has translated from the Korean, with reference to the original Chinese, the Brahmajala Sutra (The Bodhisattva Precepts). She has written various articles for magazines on the Korean way of tea, Buddhism and women, Buddhism and ecology, and Seon cooking. See Online Articles. She is interested in meditation in daily life, Buddhism and social action, religion and women's issues, Seon and its history, factual and legendary.

Official website

http://www.martinebatchelor.org/

Interview

https://web.archive.org/web/20120113125428/http://www.buddhistgeeks.com/2012/01/bg-242-practicing-at-the-crossroads

http://www.tricycle.com/sites/default/files/images/Practicing%20at%20the%20Crossroads%20-%20Pt.1.pdf

PDF: The Korean Way of Tea;

Learning from Venerable (Pangjang) Kusan Sunim;

Beopjeong Sunim’s Korean Way of Tea;

“What is This?”: Seon Practice in the Korean Tradition

by Martine Batchelor

PDF: Kusan Sunim. The Way Of Korean Zen (1985, new print 2009)

Translated by Martine Batchelor

구산수련 / 九山秀蓮 Gusan Suryeon (1908-1983), aka Kusan Sunim

PDF: What is this? Ancient questions for modern minds

by Martine and Stephen Batchelor

Wellington, Tuwhiri, 2019

PDF: Women on the Buddhist path (1996)

edited by Martine Batchelor

PDF: Walking on Lotus Flowers: Buddhist Women Living, Loving and Meditating (1996)

by Martine Batchelor

PDF: Zen (2001)

by Martine Batchelor

PDF: Thorsons WAY of Zen

by Martine Batchelor

PDF: Meditation for Life (2001)

by Martine Batchelor

PDF: Let Go: A Buddhist Guide to Breaking Free of Habits (2007)

by Martine Batchelor

PDF: Spirit of the Buddha (2010)

PDF: The Psychology of Meditation

Ed. M. West

Chap 2, Meditation: Practice and Experience by Martine Batchelor

Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2016

PDF: Mindfulness

Ed. M. Williams and J. Kabat-Zinn

Chap 10, Meditation and Mindfulness by Martine Batchelor

London and New York, Routledge, 2013, pp. 157‐164.

PDF: Women in Korean Zen: Lives And Practices

by Martine Batchelor & Son'gyong

Sunim

Syracuse University Press, 2005, 136 p.

A rare and vivid narrative of a Buddhist nun's training and spiritual awakening.

In this engagingly written account, Martine Batchelor relays the challenges a new ordinand faces in adapting to Buddhist monastic life: the spicy food, the rigorous daily schedule, the distinctive clothes and undergarments, and the cultural misunderstandings inevitable between a French woman and her Korean colleagues. She reveals as well the genuine pleasures that derive from solitude, meditative training, and communion with the deeply religious - whom the Buddhists call "good friends."

Batchelor has also recorded the oral history/autobiography of her teacher, the eminent nun Son'gyong Sunim, leader of the Zen meditation hall at Naewonsa. It is a profoundly moving, often light-hearted story that offers insight into the challenges facing a woman on the path to enlightenment at the beginning of the twentieth century. Original English translations of eleven of Son'gyong Sunim's poems on Buddhist themes make a graceful and thought-provoking coda to the two women's narratives.

Western readers only familiar with Buddhist ideas of female inferiority will be surprised by the degree of spiritual equality and authority enjoyed by nuns in Korea. While American writings on Buddhism increasingly emphasize the therapeutic, self-help, and comforting aspects of Buddhist thought, Batchelor's text offers a bracing and timely reminder of the strict discipline required in traditional Buddhism.

Introduction

FROM 1975 TO 1985, I spent ten years as a Buddhist Zen nun in Korea. I was one of the few Western nuns in the country at that time. My situation was somewhat unusual and my experiences not exactly identical to those of a Korean nun. However, I had many opportunities to live closely with them and become part of their communities. In the first part of this book, I try to present what the life of a Zen nun is like through my own experiences. This description should provide the necessary context for the second part of the book, the autobiography of a respected Korean Zen nun, Son'gyong Sunim (1903-1994).

A FRENCH LIFE

I was raised in a French family living in the countryside. My father was an engineer who built dams. As soon as one dam was finished he went to work on another, so we moved all over France. From an early age I wanted to travel and explore the world. My parents were committed humanists who were, and are still, suspicious of religion. In my teens I was concerned about the state of the world and interested in politics. I had dreams of becoming a journalist.

At the age of eighteen, however, a look at the Dhammapada, a collection of the Buddha's recommendations for living a good life, at a friend's house was a turning point for me. When I read that it might be better to change oneself before thinking of changing the world, it made sense. So I turned away from politics and became interested in meditation. Then at age twenty-two in 1975, after gathering five hundred dollars doing odd jobs, I was finally able to travel to Asia, and I ended up in Korea. To live for ten years in Korea was to penetrate a different culture and society and to discover the meaning of a meditative practice and the religious life. It was a journey of discovery of myself, of a country, of a people.

SON'GYONG SUNIM

[선경 / 仙境 Seongyeong, Sŏn'gyŏng], aka Son'gyong Sunim (1903-1994)

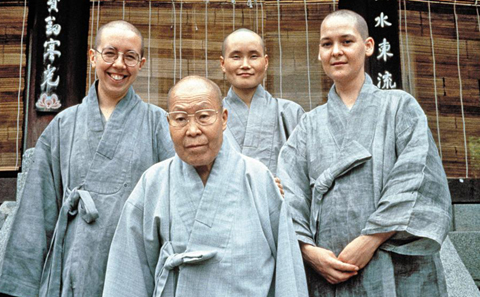

Cf. Son'gyong. “My Autobiography.” In Women in Korean Zen: Lives and Practices, ed. Martine Bachelor. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, pp. 77-103.The nunnery in Korea with which I had the strongest connection was Naewonsa, near Pusan, where Son'gyong Sunim was the leader of the meditation hall. I was deeply moved by and drawn to her humility and kindness, strength and wisdom, and would visit her regularly. She was tiny and stooped but remarkably energetic for her eighty years. My first inclination upon meeting her was always to give her a big hug, but the customs of Korean Buddhist nunneries prevented such behavior. She was very respected and much loved by the community because, as I learned while living there, she had developed the qualities of wisdom and compassion that come from along cultivation of meditation. When she was not leading the meditation in the Zen hall, following a daily schedule of ten hours of sitting and walking meditation, she would be busy gathering acorns or performing other chores for the community.

The more I got to know her, the more I appreciated her way of being, and that made me want to know more about her sixty years of life as a nun. I also thought her story would be inspiring for other people. So over a two-year period, from 1980 to 1982, she dictated her life story to me, and I recorded it. It was a delight to listen to her relate her experiences, laughing here and there at this or that adventure. I hope my translation conveys the sense of joy, openness, and lightness that is so much a part of her.

Her life spans the twentieth century. It is a bridge between the life of old Korea and new Korea, before the Korean War and after the Korean War. As I heard her stories and experiences I was taken to a different time, when life was extremely hard and poor and where one had visions and mystical dreams. When Son'gyong Sunim was born, 1903, the Korean Confucian Dynasty was in its last throes before being taking over by the Japanese in 1910. Being born into a poor peasant family meant that there really was no chance for her to develop and elevate herself in this very stratified Confucian society. Her only faint glimmer of hope for change was in becoming a Zen Buddhist nun. Her life illustrates the development that occurred for Korean nuns in the last century, from meager resources to well-supported conditions.

The life of Son'gyong Sunim is an inspiration and an example of developing one's potential and abilities. There is no doubt that her physical and psychological makeup shows her to be humble and self-deprecating, but nevertheless, repeatedly she aspires and achieves what seems to be beyond her or beyond what she could hope for or think of. She expresses some regrets about her failure to do or complete certain actions, which might have enabled her to achieve full awakening. And these regrets fit a pattern of self-criticism, but every time she changes situation, she is trying to move forward and to explore different possibilities.

It seems to me her being is her awakening, and her poems express this clearly. They are evocative, pithy, and direct and show fully her power as a realized woman.

A SHORT HISTORICAL SURVEY

Buddhism entered Korea in the fourth century. Until the twelfth century, Buddhism was supported by the state and had a strong following among the people. However, the Koryo Dynasty fell in 1392, and Buddhism dedined with the advent of the Choson period (1392-1910), which adopted Neo-Confucianism as the prevailing ideology for the country. The Choson rulers tried to restrict the spread of Buddhism: temples could not be built near towns but had to be constructed in the mountains; monks and nuns could not enter the capital and had to wear large hats to cover their faces when they went out. Yet in spite of such restrictions, the order of nuns survived.

In 1910 Korea was annexed as a colony of Japan. Although the Japanese favored Buddhism, they tried to impose their own forms of the religion, including the tradition of married clergy who were put in charge of the main temples. This change made it difficult for the celibate monks and nuns. Since the defeat of the Japanese in 1945, there has been a great revival of Korean Buddhism, halted only by the Korean War, during which time many monks and nuns had to go undercover and wear lay clothing to avoid arrest by the communists. Since the armistice with North Korea in 1953, nuns have been a strong force in the restoration of the religion, even converting abandoned monasteries into nunneries with Sutra halls for the study of Buddhist doctrine and Zen halls for the practice of meditation.

KOREAN ZEN NUNS

Few are aware of the great number of fully ordained Buddhist nuns (pikkuni/bhiksuni) living in Korea. People often are surprised that Buddhist nuns exist at all, not to mention fully ordained Zen nuns with virtually the same status in their society as monks, living in their own independent and thriving nunneries. In this book I want to show how a strong bhiksuni tradition has survived in Korea over many centuries and has proved to be both durable and adaptable to changing times.

Two thousand five hundred years ago in India, the Buddha was reluctant to ordain women. His close personal attendant, Ananda, pointed out that if the Buddha proclaimed the equality of men and women in terms of spiritual accomplishments, why could not women become Buddhist mendicants as well? So the Buddha relented and started to ordain women. They shaved their heads, wore saffron and depended on alms. As Buddhism spread in the Indian subcontinent it reached Sri Lanka, and a strong order of Buddhist nuns developed in that country. This order died out in the tenth century CE and was never reconstituted. However in the fifth century CE, Sri Lankan nuns had gone to China by sea and transmitted the full ordination to Chinese nuns, which has been preserved to this day and has also spread to Korea

The mentions of Korean nuns in historical records are relatively rare but they do appear. For example it is recorded that in 577, the Korean (Paekje) King Widok sent various texts, artisans, and bhiksunis to Japan. In 655, Bhiksuni Popmyong is said to have gone to Japan and is reputed to have cured a sick person by chanting the Vimalakirtinirdesa Sutra. There are records of queens and aristocratic ladies becoming bhiksunis like Bhiksuni Myopop, who was the wife of (Shilla) King Pophung (r. 514-546). Bhiksuni Sasin (1694-1765) was recorded as being "renowned for donations and building projects' Korean culture being very patriarchal, one cannot be surprised at the lack of written information.

In 2004 there are about ten thousand nuns (bhiksunis and sramanerikas) in Korea. Every year about a hundred novices (sramanerikas) and a hundred bhiksunis are ordained. Novices take 10 precepts and bhiksunis 348. The Koreans follow the Dharmagupta tradition of Vinaya (Rule of discipline), which was brought to the country from China and originally came from India. In total there are about eight hundred nunneries and hermitages for nuns in Korea, which include thirty-five Zen halls. Although living independent hves, the nuns until recently did not have access to the higher echelons of the Buddhist University or of the Chogye Order Headquarter, but this has changed. At the time of writing (2004), one bhiksuni has been nominated director (of culture) in the Chogye Order administration, two other nuns occupy position in this administration, and there are four bhiksuni professors at the Buddhist University of Dongguk in Seoul.

The lives of the nuns are also changing with the times. When I arrived in Korea in 1975, the country was still very poor, which was reflected in the poverty of the temples themselves, their supporters not being able to give them much financial help. Over the ten years I lived there, I could see the standards of living in Korea rise for the people and the temples, as Korean people are very generous to their religion. By the time I returned for a visit in 1992, the standards had risen again, and I found public phones in all major temples. Twelve years later, Korea has further modernized, as have the nunneries. Most nunneries have hot showers and gas fires in their kitchens, as does Songgwangsa, where nowadays many monks own and drive cars. In 2004, although the temples have considerably modernized, the same ancient and proven schedules of practice are followed in the Zen halls and similar programs of studies in the seminaries.

In Korea the nuns are as respected as the monks, and so are well supported financially by their followers. Nowadays nuns have bank accounts and some have substantial wealth. The tenth precept of novices (not accumulating gold and silver) is interpreted more liberally in Korea, a Mahayana Buddhist country, than in the Theravada countries of Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia. Generally nuns will use their wealth to create education facilities for laypeople or nuns and support welfare projects. Nowadays bhiksunis manage thirty welfare facilities, including children's welfare, elder care, women's welfare, and medical welfare. They also try to renovate their nunneries. Moreover, senior nuns are now able to send their disciples to university in Korea or abroad. Korean nuns can also fulfill a long-cherished dream to go on pilgrimage to the original Buddhist sites in India with their lay followers. Until the 1980s, most Koreans could not leave the country because of a lack of resources and political restrictions. Now that these two obstacles have been removed, one of the greatest joys of Korean Buddhist women is to travel in Buddhist countries guided by their leading nun.

MOTIVATION

When a young Korean women wants to become a nun, her motivation might come from different sources. If she comes from a Buddhist family, she has been familiar with Buddhism and the temple life from an early age. For example, Pomyong Sunim entered the nunnery when she was five years old. She was very ill; her family believed that she was going to die and that only by being sent to live in a Buddhist temple would she survive. When I met her in 1992, she had been a nun for thirty-two years. She had remained after she was cured because she liked the nunnery life so much. She had no regrets and planned to stay a nun all her life.

A young woman might be compelled to become a nun by some burning question. A nun friend, Myoljin Sunim, when she was young, used to wonder: "Why do we live?" and wanted to understand the origin of life. She decided to investigate biology and microorganisms, so she studied cytology. Although she looked deeply, she could not find anything. Then she met a Zen Buddhist who told her that through practicing Zen meditation she would understand and discover the answer to her question. By awakening, she would know herself and the essence of life.

During one holiday she went to a temple and decided to meditate very hard, hoping to complete her search by the end of that summer. One day suddenly everything became obvious, and she had an intellectual answer to all her questions. Explanations kept on rolling inside her mind, and it was so marvelous and fascinating that she kept sitting all day and night. She felt she was making a mistake, however, as the answers were only intellectual and her ideas kept revolving in a vacuum. And she developed painful headaches. She went to the master, who told her to relax and encouraged her to go beyond all these intellectual answers.

Sometimes women become nuns because of some difficulties, as a last resort, as in the case of Son'gyong Sunim, who was in great poverty and distress and thinking of suicide, and decided instead to try to be a nun for a while. In other cases, female students go to Buddhist classes and are touched by the nuns. To them the nuns look so clean and pure, and what they teach makes so much sense. Sometimes a student is impressed by a nun and wants to become like her. In the end, every nun has her own specific reasons for becoming a nun. These women who choose to become nuns often have been different in their childhood, questioning eating meat, for example. Although their parents do not like them to live celibate lives, they are not surprised by their choice of vocation. The nuns rarely regret the life outside and say that they do not long for it. Once a friend, Jiwon Sunim, told me that she became so upset in her first year at the nunnery that she took the bus and left for town. Once she got there, however, she looked around and realized it was not what she wanted, so she came back the same day.

Owing to a long tradition of Confucianism, men and women have clearly differentiated roles in Korean society. First a woman is expected to serve her father, then her husband, then her son. In the cities especially, women tend to be quite feminine and delicate. However, these expectations and tendencies are absent in the nunneries. With the nuns, one feels one is meeting human beings who have been able to develop their full potential, integrating both their female and male sides. For many Korean women, to become a nun is not a restriction but a liberation.

La Sauve 2005 Martine Batchelor

Book Reviews:

"[The] edited translation of Son'gyong Sunim's autobiography, which was dictated to Ms. Batchelor between 1980 and 1982, is an absolute treasure and provides extremely valuable first-hand information on the life of Korean nuns during the Japanese occupation period and the 'purification movement' that followed. The tales of her training under such renowned, almost legendary, teachers as Man'gong, Hanam, Kobong, and Kyongbong sunims are utterly fascinating. . . . Nothing like this has ever before appeared in a Western language."

Robert Buswell, author of The Zen Monastic Experience"The title is daunting: academic, sociological. The book

is not. Written in two parts by Martine Batchelor, it begins

with a memoir of her years as a nun in Korea, followed by a

brief “as told to” autobiography of one of her teachers, the

nun Son’gyong Sunim. It is a rare combination: both utterly

charming and highly informative.

Around the same time that Zen Master Seung Sahn

started teaching Westerners in the West, the Korean Zen

master Kusan Sunim opened Songgwangsa to Westerners

and was teaching them in Korea. Batchelor found herself

practicing with him almost by chance—she had wanted to

go to Japan but somehow the travel arrangements got fouled

up and she found herself in Seoul. It was a serendipitous

foul-up and she quickly became a student of Kusan Sunim,

and almost as quickly decided to be a nun. She practiced

as a nun in Korea for a decade until, sometime after Kusan

Sunim died, she went back into lay life. She now lives in

France with her husband, Stephen Batchelor (the author of

Buddhism Without Beliefs), himself a former monk under

Kusan Sunim; they lead meditation retreats world-wide.

Her short memoir covers a lot of ground in 74 pages.

We get a brief history of Korean Buddhism, especially of the

nuns’ order; we meet a lot of important teachers, both male

and female; we get personal matter-of-fact descriptions of

hwadu practice as Batchelor’s practice deepens and changes.

We learn about monastic etiquette; such daily details as

how one is supposed to wash (both self and clothes); four

bowl style the Korean way (slightly different from ours);

the yearly schedule with its alternating schedule of intense

kyol che’s and relaxed (by monastic standards only) hae jae’s.

There are translations of chants (some the same as ours,

some different) and the special rules for nuns. And there

are examples of Kusan Sunim’s answers to the questions

that Westerners would put to him. All of this is through

recounting Batchelor’s experience, so it is never dry and

always alive. She reports on the rigors of her training in a

completely un-self-centered way.

Quite striking is the enormous freedom she had as a nun.

A typical sentence at the beginning of a chapter is, “During

my third summer I decided to stay at Songgwangsa for the

forthcoming retreat.” It is this freedom, and her use of it to

travel and learn from many teachers, that enables her memoir

to be such a valuable record of so many practice places and so

many teachers and practitioners. While her status as a Western

nun at times made her experience somewhat different

from Korean nuns, this use of the rhythms of kyol che and

hae jae to move back and forth is not that unusual.

One of the teachers that Batchelor practiced with was the

eminent nun Son'gyong Sunim. Batchelor felt a strong connection

with her and conducted a series of interviews over several

years with the explicit goal of chronicling her life.

She chose an excellent subject, whose life story parallels

a shift within Korean society. Son’gyong Sunim, born to a

peasant family, became a nun when she was eighteen—it

was that or suicide. It was 1921, and she soon found herself

an attendant to an old nun who did not particularly value

meditation or sutra study, the preceptor of her preceptor, her

dharma grandmother. So Son’gyong Sunim stayed illiterate,

taking care of the elder nun for 15 years—not an unusual life

for a nun of that time. Then, having heard of Man Gong’s

teachings, she begged to go to a women’s temple near him; finally

the elder agreed, and a year later, when Son’gyong Sunim

refused to go back, the old nun changed her vision of what it

meant to be a nun, joined her student, and began meditation

practice. This part of Son’gyong Sunim’s biography parallels

a change in Korean attitudes towards women—while there

had always been women of accomplishment, many women,

especially women of peasant origin, had not had many

opportunities, even within monastic orders, and were not

necessarily encouraged in sutra study or in meditation. (The

situation now is radically different.)

At this point, she gained the kind of freedom that Batchelor

had, traveling from one place to another, one teacher to

another. She studied with both male and female Zen masters,

and gives accounts of both public and private (interview)

encounters with them, as well as brief biographies. Her own

description of her practice is both modest and startling in the

unassuming way she describes practice of extreme intensity.

Much of the time, despite the monastic setting, she is struggling

on her own; private interviews with teachers are rare,

and her teachers speak their words to her quite sparingly. She

gets crucial encouragement from supernatural events: waking

visions and dreams of bodhisattvas and other beings. The matter-

of-fact way that she and others describe these—oh, that

must have been Manjusri, yes he appears here sometimes—is

one of the more striking aspects of this book. This portion of

the book ends with a number of poems written by Son’gyong

Sunim. To quote one in its entirety:Clear water flows on white rock.

The autumn moon shines bright,

So clear is the original face.

Who dares say it is or is not?In summary, this book is a fine introduction to many

aspects of Korean Buddhist practice, written so gracefully

that it can be enjoyed by anyone, even if they know nothing

of Buddhism. And the dedicated practice of these women is

inspiring to our own.

Reviewed by Judy Roitman, JDPSN, Primary Point, Summer 2007, p. 21.

PDF: Women’s Buddhism, Buddhism’s women: tradition, revision, renewal (2000)

edited by Ellison Banks Findly

"Throughout Buddhism's history, women have been hindered in their efforts to actualize the fullness of their spiritual lives: they face more obstacles to reaching full ordination, have fewer opportunities to cultivate advanced practice, and receive diminished recognition for their spiritual accomplishments." "Here, a diverse array of scholars, activists, and practitioners explores how women have always managed to sustain a vital place for themselves within the tradition and continue to bring about change in the forms, practices, and institutions of Buddhism. In essays ranging from the scholarly to the personal, Women's Buddhism, Buddhism's Women describes how women have significantly shaped Buddhism to meet their own needs and the demands of contemporary life."--Jacket

Includes bibliographical references (pages 451-479) and index

1. Ordination, affiliation, and relation to the sangha. The nuns at the stūpa : inscriptional evidence for the lives and activities of early Buddhist nuns in India / by Nancy J. Barnes -- Women in between : becoming religious persons in Thailand / by Monica Lindberg Falk -- Voramai Kabilsingh : the first Thai bhikkhunī, and Chatsumarn Kabilsingh : advocate for a bhikkhunī sangha in Thailand / by Martine Batchelor -- Buddhist action : lay women and Thai monks / by H. Leedom Lefferts, Jr. -- Western Buddhist nuns : a new phenomenon in an ancient tradition / by Bhiḳsuṇī Thubten Chodron --Sakyadhītā in Western Europe : a personal perspective / by Rotraut Wurst -- Novice ordination for nuns : the rhetoric and reality of female monasticism in northwest India / by Kim Gutschow -- An empowerment ritual for nuns in contemporary Japan / by Paula K.R. Arai

2. Teachers, teaching, and lineages. Women teachers of women : early nuns "worthy of my confidence" / by Ellison Banks Findly -- Achaan Ranjuan : a Thai lay woman as master teacher / by Martine Batchelor -- Patterns of renunciation : the changing world of Burmese nuns / by Hiroko Kawanami -- An American Zen teacher / by Trudy Goodman -- Teaching lineages and land : renunciation and domestication among Buddhist nuns in Sri Lanka / by Nirmala S. Salgado -- Transformation of a housewife : Dipa Ma Barua and her teachings to Theravāda women / by Amy Schmidt -- My dharma teacher died too soon / by James Whitehill

3. Political and social change. Women changing Tibet, activism changing women / by Serinity Young -- The Women's Alliance : catalyzing change in Ladakh / by Helena Norberg-Hodge -- Sujātā's army : Dalit Buddhist women and self-emancipation / by Owen M. Lynch -- Religious leadership among Maharashtrian women / by Eleanor Zelliot -- Jamin Sunim : prison work for a Korean nun, Myohi Sunim : a Korean nun teacher of elderly women, and Pomyong Sunim : flower arranging for the Korean lay / by Martine Batchelor -- Women, war, and peace in Sri Lanka / by Tessa Batholomeusz -- Mae Chi Boonliang : a Thai nun runs a charitable foundation, and Mae Chi Sansenee : a Thai nun as patroness / by Martine Batchelor -- Diversity and race : new koans for American Buddhism / by Janice D. Willis

4. Art and architecture. From periphery to center : Tibetan women's journey to sacred artistry / by Melissa Kerin -- Performing maṇḍalas : Buddhist practice in transition / by Judy Dworin -- Women, art, and the Buddhist spirit / by Ann W. Norton -- Space as mind/maṇḍala places : Joan Halifax, Tsultrim Allione, and Yvonne Rand / by Sarah D. Buie. 5. Body and health. Sickness and health : becoming a Korean Buddhist shaman / by Hi-ah Park -- Tokwang Sunim : a Korean nun as medical practitioner / by Martine Batchelor -- How a Buddhist decides whether or not to have children / by Kate Lila Wheeler -- Theanvy Kuoch : Buddhism and mental health among Cambodian refugees / by Theany Kuoch -- Women's health in Tibetan medicine and Tibet's "first" female doctor / by Vincanne Adams and Dashima Dovchin

Appendix: Stephen Batchelor

PDF: Confession of a Buddhist Atheist

by

Stephen Batchelor

Cf.

Chapter 6: Great Doubt

PDF: Buddhism Without Beliefs

by Stephen Batchelor

PDF: The Faith to Doubt: Glimpses to Buddhist Uncertainity

by Stephen Batchelor

Berkeley, Parallax Press, 1990