ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

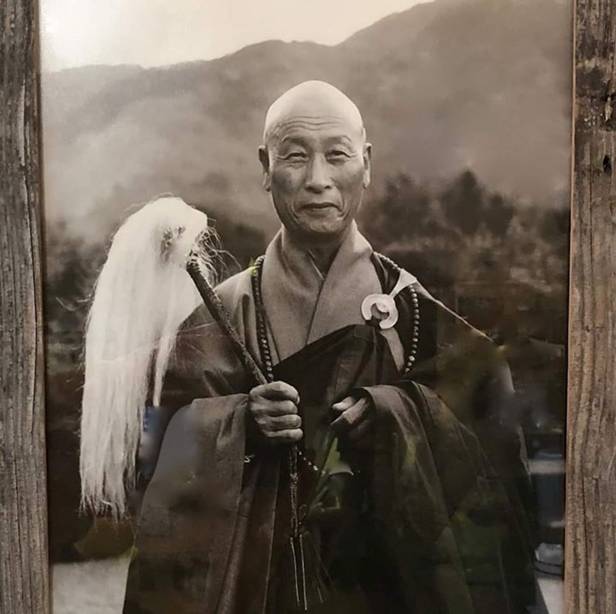

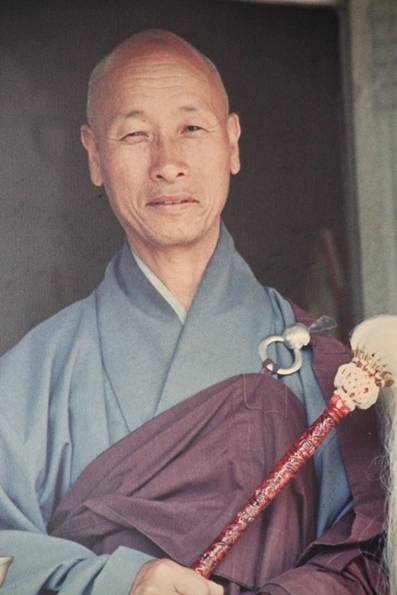

구산수련 / 九山秀蓮 Gusan Suryeon (1908-1983), aka Kusan Sunim

(Magyar átírás:) Kuszan Szuljon

Kusan Suryeon (1909-1983)

http://www.koreanbuddhism.net/master/priest_view.asp?cat_seq=10&priest_seq=4&page=1

Spending fifteen years as the first Patriarch of the Jogye-san Monastic Compound(Jogye Chongnim) headquartered in Songgwang-sa, Master Kusan devoted much his life's energy to propagating Buddhism, through such activities as the founding of the Bulil International Seon Center. Directly and indirectly, some fifty of his disciples from both Korea and abroad are spreading the teachings of Korean Seon Buddhism around the world.

Career

Master Kusan was born December 17, 1909, in a small village in Mt. Jirisan in Namwon, Jeollabuk-do province. At the age of 14, after his father's sudden death, he took over management of his father's barber shop and family affairs, spending his young years in anguish. At 25, after coming down with an unknown illness, his moans of agony were interrupted by the words of a wandering Buddhist ascetic. “The body is the mind's reflection. Since the seat of one's original nature is pure, where can disease take root?” Hearing these words gave Kusan a sudden religious awakening. At that moment he decided to head to Yeongwonsa Monastery on Mt. Jirisan, to take part in a 100-day practice of devotion to the Bodhisattva Gwaneum. With his disease cured during the 100 days of prayer, Kusan decided to be ordained into the sangha. In 1937 at the age of 28, he received the precepts to become a novice monk at Songgwangsa Monastery from Master Hyobong.

Following this, with Songwangsa as his base, Master Kusan spent five years practicing ardently at various meditation halls (Seonwon). In 1943, to engage in serious practice, he built the “Correct Awakening” (Jeonggak) hermitage near the Sudoam Hermitage at Cheongamsa. For two years, he practiced with ferocity. In 1946, his master Hyobong became the first Patriarch of the Gayasan Monastic Compound (Gaya Chongnim) headquartered in Haeinsa, and Master Kusan took on the administrative responsibilities of the temple and also built and resided in the Beobwangdae Hermitage, midway up Mt. Gayasan, all while maintaining a diligent training regimen. In 1950, with the onset of the Korean War, the monks of Gayasan Monastic Compound scattered, and Kusan went to Eungseoksa in Jinju where he continued his Seon investigation. During the winter retreat in 1951, at the age of 42, Kusan penned his verse of enlightenment and submitted it to Master Hyobong:

The world's outer appearance is originally emptiness

Do people point to emptiness because the mind resides there?

For the withered tree above the crags, there are no seasons

when spring arrives flowers bloom, in fall, it bears fruit

Master Hyobong accepted this verse and endorsed Kusan's enlightenment. Beginning in 1954, he assisted Master Hyobong as an avid supporter of the Buddhist purification movement. In 1966, with Master Hyobong's passing, Kusan returned to Songgwangsa, following his master's dying request to “restore Songgwangsa [which was mostly destroyed in the Korean War] and train many great people there.” Following the developments at Haeinsa, after three years effort the Jogyesan Monastic Compound (Jogye Chongnim) was established, the second Chongnim in Korea, at Songgwangsa in 1969.

As the first patriarch of the Monastic Compound, Master Kusan instituted a fundamental training program for his disciples, and as one of the three jewel temples, Songgwangsa, the “Sangha Jewel Monastery,” overflowed with the energy of its vivid restoration, the likes of which had not been seen since the days of National Master Bojo Jinul. To say nothing of the Korean monks, monks from the United States, Europe and elsewhere also came to Songgwangsa, constantly maintaining the highest levels of intensity in their training. In 1973, after attending the inaugural service at Sambo-sa in Carmel, California, in the United States, Kusan returned to Songgwangsa with a few foreign disciples and other practitioners to found Korea's first international Seon meditation center, “Bulil International Seon Center,” opening a new chapter in the globalization of Korea's traditional Seon teachings. Kusan continued along these lines, pouring his energy into the international propagation of Korean Buddhism, founding temples around the world, including Goryeosa in Los Angeles in 1980, Bulseungsa in Geneva in 1982, and Daegaksa near Carmel, California.

One day the following year, in 1984, as the restoration of Songgwangsa, together with the winter retreat, was coming to an end, Kusan let his disciples know that the karma of his life here was meeting its completion and left behind the following requests: “don't give my body any injections, perform the cremation in sitting meditation posture, live together in harmony without harm to the Seon tradition, do not live as a monk deceiving yourself, and devote yourself continuously to awakening.” He also left his “death verse”:

As the leaves of fall burn more crimson than the flowers of spring

All of creation is completely laid bare

As living is empty, and dying too, is also empty

I go forth smiling, within the ocean-like absorption of the Buddha

On the afternoon of December 16th, at the Samiram Hermitage in Songgwangsa where he had first met his master Hyobong, surrounded by his many followers, Kusan assumed the lotus position and his seventy-four years of life came to a quiet end with his passing into nirvana.

Writings

Among Master Kusan's written works are his 1975 book, Seven Perfections, aimed at bringing Buddhism back into daily life, and his 1976 book, Nine Mountains, an English version of his dharma talks, written for the benefit of his foreign disciples. After receiving much attention from scholars of Buddhism and eastern philosophy around the world, Nine Mountains was revised and published in Korean as Seok Saja (Stone Lion). After Master Kusan's passing, his foreign disciples published Seon! My Choice, a compilation of their impressions and experiences regarding Korean Buddhism and their Seon training at the Bulil International Seon Center. In 1985, Master Kusan's disciples Stephen Batchelor and Martine Fages edited an English compilation of his dharma teachings, The Way of Korean Zen. The Society of Kusan Followers also published Kusan Seonmun (Seon Teachings of Kusan) in 1994, a volume of the Master's Seon sermons, and Kusan Seonpung (Seon Tradition of Kusan)in 1997, a collection of his dharma sermons delivered in the early 1980s while touring the United States, Taiwan, Europe and elsewhere.

Doctrinal Distinction

Master Kusan's practice was an exhaustive hwadu training. After gaining experience with the hwadu, “what is this?” Kusan then took up Zhaozhou's “MU” hwadu, leading his disciples in this practice as well. This hwadu was meant to lead one to understanding the state of mind that exists before saying “MU!” Kusan described his struggle this way:

“Investigating this hwadu, my investigation and the saying of “mu” coincide. In this state, I come even to defer sleep and forget meals. Standing alone, I reach to the point where I am alone, facing every enemy I've ever made during the past 10,000 years, wanting to sleep but unable, put in a position where I cannot go left or right, straight ahead or back, until finally, the place I have been leaning on exists no more, and I become unafraid of tumbling into emptiness. Thereafter, one day, I suddenly yell, 'Ha!,' and I'm left feeling as if heaven and earth have been overturned. When other people enter this place whose depth is unfathomable, they laugh out loud to themselves and do nothing but smile.”

He also explained that even after achieving an awakening, until you are able to precisely communicate your experiences to others, while pushing yourself to continuously refine your own opinions and understanding, you must engage in purification practices; then you must work to relieve the sufferings of all sentient beings.

Though Master Kusan spent 45 years practicing his hwadu with precisely this kind of discipline, he never stinted from getting involved in doing the work of the Buddha. Whenever he had a spare moment free from his practice, he could not keep still, such that he earned the nickname, “the working monk.”

Moreover, he never failed to join with the rest of the Buddhist community to participate in worship services, cooperative cleaning or building efforts, food offerings, or other such activities. In this way, the ever-thoroughly practicing Master Kusan emphasized the practice of making Buddhism a part of daily life, based on the idea that it was wrong to think of Buddhism as the sole preserve of a singular class of people, like monks and nuns, or that you have to live in the mountains to practice. Combining these methods under one teaching, Master Kusan promoted the “seven perfections” movement. He taught that a good way for Buddhist practitioners to implement the truth of Buddhism within their daily lives was to use six days of each week to practice each of the six bodhisattva perfections: charity on Monday, morality on Tuesday, perseverance on Wednesday, effort on Thursday, meditation on Friday, and wisdom on Saturday, and then to use Sunday as a service day, the day to practice the perfection of all works together.

Master Kusan Sunim (1908-1983)

Korean Zen Master Kusan ("Ku" - Nine; "San" - Mountains), known as Kusan Sunim, was considered the greatest living Zen Master in South Korea toward the end of his life. He passed on in December, 1983, at the age of 74, at SonggwangSa Zen monastery outside Gwangju, Korea, and was a magnet for sincere Zen students from not only around Korea, but from around the world.

He traveled, lectured, and presided over Zen retreats in North America and Europe. From the mid 1970s, a "foreign sangha" made up of both men and women from Sri Lanka, Singapore, England, Denmark, Australia, Canada, Germany, and the United States were drawn to Korea by the reputation, teachings, and powerful presence of this remarkable monk.

His book of teachings, Nine Mountains , was republished and edited by two of his European students, Stephen Batchelor and Martine Fages (now Batchelor) as The Way of Korean Zen . This book details his radical emphasis on questioning, the heart of the Koan (kong-an) practice of the Korean Zen Buddhist approach. He was constantly challenging the monks and seekers who came to him with abrupt and forthright questions, such as, "right now, tell me, what is the sky?" His book also details his biography, and how he had practiced extremely diligently for many years, and as a result of his supreme effort attained profound breakthroughs. At times, he allegedly did standing meditation so long without moving that birds came and picked at this cotton clothes to make nesting material for their nests.

He lived simply and strictly as a vegan Zen monk. He was a bright, radiant, challenging, freeing, and magnetic presence. After his passing, and the cremation of his body, many sarira, or jewel-like "relics" were found among his ashes, a type of proof of his powerful transformation of consciousness. These are on display at Songgwangsa temple.

Source: Will Tuttle, Ph.D.

PDF: Nine Mountains

by Kusan Suryŏn

PDF: The Way of Korean Zen by Kusan Sunim

translated by Martine Batchelor

Weatherhill, 2009

The power and simplicity of the Korean Zen tradition shine in this collection of teachings by a renowned modern master, translated by Martine Batchelor. Kusan Sunim provides a wealth of practical advice for students, particularly with regard to the uniquely Korean practice of hwadu, or sitting with questioning. An extensive introduction by Stephen Batchelor, author of Buddhism without Beliefs, provides both a biography of the author and a brief history of Korean Zen.

Extract :

Ten Ox-Herding Pictures (심우도)

Verse and commenary by 구산 수련 Kusan Suryŏn

Translated by Martine BatchelorFROM - CHAPTER FIVE

http://www.wisdom-books.com/ProductExtract.asp?PID=18573HWADU MEDITATION

A human being is composed of a body and a mind. A body without a mind is just a dead corpse. A mind without a body is just pure spirit. Someone who, although endowed with both a body and a mind, only knows the body but not the mind is called a sentient being. In general, a sentient being is understood as any being possessing conscious life. Birds flying in the sky, animals walking on the ground, fish swimming in the water, as well as the tiniest organisms, are all sentient beings.

Human beings are said to be superior to all other crea¬tures. But how can a human being be considered superior if he knows his body but is ignorant of the nature of his mind? One who knows the body but not the mind is an incomplete person. However, if a human being searches for

Meditation can be compared to a battle between wandering thoughts and dullness of mind on the one side and the hwadu on the other. The stronger the hwadu becomes, the weaker will become wandering thoughts and dullness.

You are not the first and you will not be the last to tread this path. So do not become discouraged if you find the practice difficult at times. All the previous patriarchs of old as well as the contemporary masters have experienced hardships along this way. Moreover, it is not always the most virtuous or intelligent person who makes the swiftest progress. Sometimes the opposite is true. There are many cases of troublesome and ill-behaved people who, upon turning their attention inward to the practice of meditation, have quickly experienced a breakthrough. So do not feel defeated even before you have really begun.

An ancient master once said that with the passing of the days you will see your thoughts becoming identical with the hwadu, and the hwadu becoming identical with your thoughts. This is quite true. In the final analysis, the practice of Zen can be said to be both the easiest as well as the most difficult thing to do. However, do not thereby deceive your¬self into thinking that it will be either very simple or ex¬tremely hard. Every morning just resolve to be awakened before evening. Strengthen this commitment daily until it is as inexhaustible as the sands along the river Ganges.

There is no one who can undertake this task for you. The student's hunger can never be satisfied by his teacher's eating a meal for him. It is like competing in a marathon. The winner will only be the person who is either the fittest or the most determined. It is solely up to the individual to win the race. Likewise, to achieve the aim of your practice, do not be distracted by things that are not related to this task. For the time being, just let everything else remain as it is and put it out of your mind. Only when you are awakened will you be able to truly benefit others.

Be careful never to disregard the moral precepts that act as the basis for your practice of meditation. Further¬more, do not try and look deliberately withdrawn or abstracted. It is quite possible to pursue your practice of Zen without others being aware of what you are doing. However, when your absorption in the hwadu becomes particularly intense, your attention to external matters may diminish. This might result in your looking rather out of touch with everyday concerns. At this time the hwadu is said to be ripening and the mind starts to become sharper and more single-pointed, like a fine sword. It is vital at this point to pursue your practice with the intensity of an attacking soldier. You must become totally involved with the hwadu to the exclusion of everything else.

If you can make your body and mind become identical with the hwadu, then in the end ignorance will naturally shatter. You will fall into a state of complete unknowing, perplexity, and questioning. Those who have done much study will even come to forget what they had previously-learned. But this is not a final or lasting state. When you have reached this point you must still proceed further to the stage where although you have ears, you do not know how to hear; although you have eyes, you do not know how to see; and although you have a tongue, you do not know how to speak. To reach the place where mountains are not mountains and rivers are not rivers may entail several years of hard practice. Therefore, it is necessary to cast aside all other concerns and train yourself to focus the entirety of your attention on the tasteless hwddti alone.

By practicing diligently in this manner, you will finally awaken. Then you can seize the Buddhas and the patriarchs themselves and defeat them. At that time mountains will again be mountains, rivers will again be rivers, the earth will be the earth and the sky will be the sky. When you experience things in such a way, then you should proceed to a qualified teacher to receive confirmation of your understanding.

Kusan Sunim in Buddhism Now

http://buddhismnow.com/category/kusan-sunim/

PDF: Turning the Wheel of Dharma in the West: Korean Son Buddhism in North America

by Samu Sunim (Kim, Sam-Woo)

pp. 241-247.

In: Korean Americans and their religions : pilgrims and missionaries from a different shore

edited by Ho-Youn Kwon, Kwang Chung Kim, and R. Stephen Warner. 2001. Chapter 13: pp. 227-258.

Ku Szán

In: Buddha tudat, Zen buddhista tanítások. Ford., szerk. és vál. Szigeti György

Budapest, Farkas Lőrinc Imre Könyvkiadó, 1999, 134-138, 169-170. oldal

KU SZÁN (1909-1983) - a XX. század egyik leghíre-

sebb koreai zen mestere. Huszonhat éves korá-

ban súlyos betegen felment a Csiri-hegyre, és

száznapos visszavonulásba kezdett. A visszavo-

nulás végére meggyógyult, és három évvel ké-

sőbb letette a szerzetesi fogadalmakat Hjo Bong

zen mesternél. Idejét főként a meditációnak

szentelte, majd 1943-ban elérte a megvilágoso-

dást. A következő három évben Hjo Bong zen

mester mellett élt a Hein-sza kolostorban.

1947-ben a zen mester megadta neki az inkát, s

Ku Szán a Mire kolostorba költözött, ahol apát-

ként tevékenykedett.1957-ben a Pegun remetelakba költözött, ahol

hároméves meditációs gyakorlatba kezdett.

1960-ban, ötvenéves korában, megvalósította a

nagy felébredést. Nem sokkal később Hjo Bong

szertartásosan átadta neki a Tant.A mester 1966-ban bekövetkezett halála után

Ku Szán lett a Tonghva kolostor apátja. 1969-

ben a Szong-kvang kolostorba költözött, s ott

munkálkodott az elkövetkezendő tizenkét év-

ben. 1983-ban szélütést szenvedett, s december

16-án meghalt.

Négy dolog

Buddha azt mondta, hogy négy dolgot nagyon nehéz

megszerezni. (1) Nehéz embernek születni. (2) Nehéz

a Buddha-Dharmával találkozni. (3) Nehéz az otthont

elhagyni (szerzetessé válni). (4) Nehéz éles szemű mes

terrel találkozni.

A Buddha a tudat

A Buddha a tudat, a tudat a Buddha. Miért keresitek a

Buddhát a tudaron kívül? A tudaton kívül nincs Buddha,

a Buddhán kívül nincs tudat. Ha ráébredünk a

tudatunkra, meglátjuk az igazi Buddhát. S akkor kéz a

kézben sétálunk a múlt, a jelen és a jövő Buddháival.

A bölcsesség szeme

Ha nem látjuk az igazi természetünket, hétköznapi

emberek vagyunk. Ha tisztán látjuk az igazi természe

tünket, megvilágosodottak vagyunk, s a világot a böl

csesség szemével szemléljük, Látjuk, hogy valójában

nincs szín, hang, szag, íz, tapintás és tudati folyamat.

Mindenki Buddha lehet

Láthatjuk, mindenkinek megvan a lehetősége, hogy a

tudatát művelje, ráébredjen igazi természetére, és elér-

je a buddhaságot. S bizony, ez nem könnyű feladat.

Szamszára és nirvána

Amikor felismerjük, hogy a dharmák létezése és nem-

létezése se nem azonos és se nem különböző, akkor a

szamszárát és a nirvánát egylényegűnek látjuk.

Hínajána tudat

A hínajána (kis-szekér) tudat bár felébredett, mégis az

ürességhez ragaszkodik. A formavilágot illúziónak lát

ja, és önös boldogságot élvez az ürességben. Először be-

lép az üresség kapuján, majd elmélyed a nyugalomban.

Mahájána tudat

A mahájána (nagy-szekér) tudat belép az üresség kapu

ján, azután továbblép a száz láb magas pózna csúcsáról,

és belátja, hogy a feltételhez kötött és a feltétel nélküli

létezők egyike sem duális. Amikor egy megvilágoso-

dott tudat szemléli a létezőket, nem tesz különbséget a

földi és a mennyei lét között, a Buddhák és az érző lé-

nyek között.

Zen tudat

A zen (legfőbb-szekér) tudat felismeri, hogy a hétköz-

napi emberek és a tökéletesen megvilágosodottak kö-

zött nincs különbség: hogy az érzékcsalódás és a meg-

világosodás mentes a kettősségekről: hogy a jó és a

rossz gyökértelen; hogy a Szaha-világ és a Tiszta Föld

ugyanaz; hogy a szamszára és a nirvána tökéletesen azo-

nosak; hogy az érzékelhető és az érzékelhetetlen jelen-

ségek megkülönböztethetetlenek, Ez a nirvána, az el-

lobbanás tudata, a tökéletes szabadság tudata, a nagy

megszabadulás tudata.