ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

Janwillem van de Wetering (1931-2008)

Tartalom |

Contents |

| Janwillem van de Wetering: Az üres tükör Szentendre, 1999 Fordította: Farkas Tünde |

PDF: Inspector Saito's Small Satori (short stories) The Philosophical Exercises of Janwillem van de Wetering PDF:

Portraying Zen Buddhism in the Twentieth Century: Encounter Dialogues as Frame-Stories in Daisetz Suzuki's An Introduction to Zen Buddhism and Janwillem Van de Wetering's The Empty Mirror |

![]()

Born in Rotterdam in 1931, Van de Wetering started his writing carreer as a bit of a vagabond. He has traveled, engaged in business, studied at a Zen Monastery in Japan (1958-1959), and was a policeman in Amsterdam. In 1975, he settled on the coast of Maine in the United States.

As he describes part of his life on a commercial website (1997):

For ten years (1965-1975) van de Wetering knew prosperity while building an export network for his wife's family's company's textile product. Philosophical curiosity was aroused again when he met Trungpa Rimpoche at a Tibetan Buddhist retreat in Scotland. Studies at "The Tail of the Tiger" led to visits to another metaphysical hot spot. "Moon Spring Hermitage", led by a fellow, much senior disciple of the, now dead, Japanese abbot, on the Maine coast, U.S.A. Meanwhile, back in Holland, van de Wetering had joined the Amsterdam Reserve Constabulary. Having traveled as a young man in territories beyond Dutch jurisdiction without keeping in touch with Dutch authorities brought a charge of dodging the draft. Military Police suggested that, in order to avoid arrest, it would be appropriate to serve the queen in voluntary law enforcement. The period was to be for four years (two years training, two years patroling Amsterdam evenings and weekends) but got extended to seven years as subject passed sergeant and inspector exams. The idea of being an anarchist in police uniform seemed surreally interesting. The textile trade was "getting old" by then and, looking for a way to change his career he had his Zen journals, referring to both the Japanese and American monastic periods, published.

Van de Wetering studied Zen under the guidance of Oda Sessō, together with Walter Nowick, at Daitoku-ji. Van de Wetering lived a year in Daitoku-Ji and half a year with Nowick and described these in The Empty Mirror. Van de Wetering describes a visit to the monastery by the highly respected Hugo Enomiya-Lassalle, describing his own mixed thoughts about this representative of what he deemed an old-fashioned religion. Sōkō Morinaga, Walter Nowick's Dharma brother, wrote in Novice to Master about traditional practices at that time.

His many travels and his experiences in a Zen Buddhist monastery and as a member of the Amsterdam Special Constabulary "being a policeman in one's spare time" as he phrased it in his introduction to Outsider in Amsterdam) lent authenticity to his works of fiction and nonfiction.

Van de Wetering was awarded the French Grand Prix de Littérature Policière in 1984.

PDF: Inspector Saito's Small Satori

As a member of Amsterdam's Special Constabulary, he gained some insights that gave rise to his now famous police procedural series, eight books to date, featuring Adjutant Grijpstra and Sergeant De Gier, but he also ventured into other literary fields.

The Empty Mirror and A Glimpse of Nothingness, personal tales of the Zen experience, reflect his Buddhist training in a frame of understatements that are hard to surpass, and the present book, Inspector Saito's Small Satori, approaches the basic mystery from yet another angle.

While living in a Zen monastery in Japan, Van de Wetering located a copy of Parallel Cases Under the Pear Tree, a thirteenth-century manual on detection and jurisprudence. The volume, which quotes 144 criminal cases solved by Chinese magistrates, was translated by another famous Dutchman, the sinologist Dr. Robert van Gulik.

The discovery inspired Van de Wetering to create a new hero—the present-day Inspector Saito of the Kyoto Municipal Police. The young detective is an erratic aristocrat who stumbles subtly along, helped, at times, by his peers, an ancient Zen master who observes the illusionary world from a shack on a mountaintop, and Uncle Saito, a cynical ex-business tycoon retired in the coastal town of Suyama.

—«»—«»—«»—

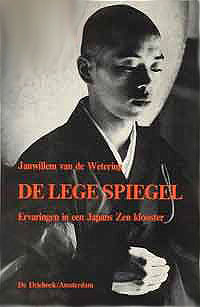

De lege spiegel / The Empty Mirror: Experiences in a Japanese Zen Monastery (1971)

Publié en français sous le titre Le Miroir vide, Paris, Seuil, 1978; réédition, Paris, Rivages/Poche. Petite bibliothèque no 310, 2000

Het Dagende Niets / A Glimpse of Nothingness: Experiences in an American Zen Community (1975)

Publié en français sous le titre Un éclair d'éternité, Paris, Mercure de France, 1979; réédition, Paris, Presses-Pocket no 4702, 1991; réédition, Paris, Rivages/Poche. Petite bibliothèque no 278, 1999

Zuivere leegte / Afterzen: Experiences of a Zen Student out on His Ear (1999)

Publié en français sous le titre L'Après-zen, Paris, Payot & Rivages, Bibliothèque Rivages, 2001; réédition, Paris, Rivages/Poche. Petite bibliothèque no 421, 2003

Nearly 30 years ago, van de Wetering, who would later achieve fame as a mystery novelist, published The Empty Mirror, about his experiences at a Zen monastery in Japan in the mid-60s. In 1975, he published a sequel, A Glimpse of Nothingness, about his stint at the Moon Springs Hermitage in Maine. Now the author has written a follow-up, AfterZen, told from the perspective of an aging soul who dropped most formal Zen practice years ago but still carries an abiding respect for the gut truths of the teaching and for at least some of its teachers. Much of the book has the air of the classic Zen saying, "If you see the Buddha on the road, kill him": with humor and occasional crankiness, van de Wetering knocks koans, meditation and some of the trappings of the monastic Zen life. There are many flashbacks, to Japan, to his American experiences, to meetings with fellow ex-students, and the book has a somewhat chaotic feel, rather more like life than art. Throughout, van de Wetering's voice is sincere, if iconoclastic. Those looking for composed wisdom should read Basho; those looking for an honest memoir by a perhaps wise man will find this to their taste. (Publishers Weekly)

In "Afterzen," van de Wetering provides unorthodox solutions to a collection of classical koans found in Walter Nowick's "The Wisteria Triangle." Van de Wetering gives them his own distinctive touch of humor, down to earth reality, and tough spirituality in the context of meeting and adventures with personalities "collaged from bits and pieces of teachers and fellow students who kindly came my way." In this third book of the trilogy, van de Wetering is at his accessible, honest, funny, and genuinely spiritual best.

Janwillem van de Wetering's "The Empty Mirror": Book Review

by

John L. Murphy / "Fionnchú"

http://fionnchu.blogspot.hu/2011/11/janwillem-van-de-weterings-empty-mirror.html

This iconoclastic memoir provides one of the earliest "I went to Asia and tried to find enlightenment" narratives from what became the counterculture. After philosophy studies, affairs, working here and there, at 25 or so, in postwar Japan, van de Wetering winds up in Kyoto, ringing a bell he should not to enter a monastery to study Zen as a voluntary monk. As a Dutchman with no knowledge of the language or culture, he stands out in many ways; he says that he was among only 27 Westerners in Kyoto in 1958. His brisk, reflective, but restless and anarchic account shows what few back then witnessed: how, just as for others Zen met Beats, a fidgety young man seeks to better himself and to find truth amidst a world he seeks and flees from alternately.

Buddhism appeals to him as "a possible path, not a vague theory" that refuses certainty but eschews "questions about the why of everything" by "a disregard of doubt." (32) If the Buddha could do it, and others could follow this way, van de Wetering figures it aligns better with his skeptical mindset than other methods. He seeks to cut down his self without committing suicide.

He tries to get over logical ruminations or god-centered ideas. His master, once a neurotic boy, now a composed presence, encourages his wayward student: "The intellect is a beautiful instrument and has a purpose, but here you will discover a different instrument. When you solve 'koans' you will have answers which are no longer questions." (51)

Unlike his fellow, native monks, who get a somewhat easier way to solve koans to speed their way along the standard three-year stint required before they are ordained to take over temples and make their careers, as a volunteer monk and a foreigner, van de Wetering struggles against the regimen. He feels like a "circus bear" compared to the native-born monks apart from whom he lives in a tattered dirty cell. He knows that the Japanese work by many written laws, but also unwritten ones that keep them from killing themselves too often, so he learns with Peter and Gerald, fellow Zen "gaijin," how to balance his life with the monastic rigor.

He barely masters the half-lotus position, and how he can meditate remains to him and to the reader a mystery. He tries to stick with it for a year and a half. Anticipating the regular sessions of intensified practice: "that was why I had come, to visit an old Japanese gentleman who ridiculed everything I said or could say, and to sit still for fifteen hours a day on a mate, for seven days on end, while the monks whacked me on the back with a four-foot log lath made of strong wood." (79)

Peter reasons about "now" being synonymous with eternity, and doing what one must "now" for it to happen. Van de Wetering muses how so many answers given in Zen seem "brilliant, deduced from the one and only reality, but which I couldn't make use of because as soon as I started to have a good look at such an answer its message proved to be well outside my reach." (113) He seems to resist giving in to the compassion and detachment he admires and which he knows must be sought in dharma. But, in typical Zen form as non-form, is his master even a Buddhist? Han-san answers his pupil: "Is a cloud a member of the sky?" (140)

The later part of his stay gets blurred over. A shift inside's weakened him, but I felt this stayed too distant from the reader. It means he lives outside the walls of the monastery, with Peter as his tutor, but Janwillem appears to slacken in his discipline, as his wanderlust appears to return, and eventually he leaves Kyoto with little formal notice. He respects those he leaves behind, however, and this remains a jittery, self-deprecating, and honest attempt to make sense, fifteen years later, of what must have marked the author indelibly. For at his departure into where the "world is a school where the sleeping are woken up," the master tells him that he "is now a little awake, so awake that you can never fall asleep again." (146)

The Philosophical Exercises of Janwillem van de Wetering

by Henry Wessells

Author of a highly acclaimed series of mystery novels, world traveller, former Zen student, and former police officer Janwillem van de Wetering brings an unusual perspective to the detective genre. His novels and stories feature a diverse and richly drawn cast of characters and settings that range from the streets of Amsterdam to the Caribbean and from rural Maine to Japan, South America, and New Guinea. A careful eye for the details of police investigations is joined with a quirky sense of humor and a keen interest in philosophical and spiritual matters.

With publication of Outsider in Amsterdam, van de Wetering gained a following in both Europe and America. In this novel and others in the series, van de Wetering created one of the more unusual detective teams in modern crime fiction: the trio of “Amsterdam Cops”: Sergeant Rinus de Gier, youthful, handsome, and highly athletic; Adjutant Henk Grijpstra, somewhat older and more phlegmatic; and the unnamed commissaris, their senior officer and spiritual guide. Outsider in Amsterdam, with a plot that involves spiritual fraud and reflections on Western ideas about the exotic East, explores in fictional form ideas that had long been a concern of the author. Philosophical and existential questions are intertwined in all of his subsequent novels.

His first published book, The Empty Mirror, was a nonfiction account of his experiences as a Zen student in Japan in the late 1950s; it appeared in Dutch in 1971, and in an English edition in 1973. A companion volume, Glimpses of Nothingness, recording impressions during a stay in an American Zen community, appeared in 1975. Van de Wetering published four children’s books that explore spiritual and philosophical themes. His 1987 biography of Dutch mystery author and diplomat Robert van Gulik (reissued in paperback by Soho Press in June 1998) is similarly concerned with understanding spiritual matters. Most recently, a collection of van de Wetering’s essays entitled Afterzen has just been published by St. Martin’s Press.

Before he turned his hand to writing, van de Wetering lived on four continents and his varied experiences pop up throughout his novels and stories. His years in Japan give a rich texture to The Japanese Corpse and the stories that make up Inspector Saito’s Small Satori, while Mangrove Mama is a recent collection of stories that evoke van de Wetering’s memories of England, Japan, South Africa and South America as well as more recent travels to Key West and New Guinea.

Janwillem Lincoln van de Wetering was born in Rotterdam, The Netherlands, on February 12, 1931. His father was a merchant whose American contacts prompted him to give his second son the middle name, Lincoln. The signal event of his childhood was the Second World War: “When the Luftwaffe bombed Rotterdam the Junckers (obsolete cargo planes, bombs were thrown out by hand) stopped two streets short of our house.” One of the stories in van de Wetering’s collection The Sergeant’s Cat, “Jacob Sanders,” is the first chapter of a projected novel set during the Nazi occupation of Rotterdam, that features “many of my own adventures.”

I was 14 when the war was over and had become difficult to handle so my parents sent me to graduate (age 16) at a country school and I lived in a teacher’s house. After that I ran away and worked at a farm until my father tracked me down. I then studied at the Castle of Nijenrode College, an elite “business management” school that has since become Nyenrode University (the name was anglified). Rotterdam, where I grew up, is a city of hard working folks who save. They spend some of their savings in Amsterdam which is a center of the arts, has a famous pleasure quarter, and collects the odd and weird. Rotterdam people are straight, they work, then they die. This may be a biased opinion. I never went back to check and they now have famous film and jazz festivals. Maybe I'll go back when I am older. Merely thinking about going there gives me asthma.

After graduating at age 19, van de Wetering worked for a year in Amsterdam and then set out for Cape Town, South Africa, where a job had been arranged through a company connected with his father’s interests. Life in Cape Town proved very attractive and he refused a transfer to Johannesburg, whereupon his father fired him. “Working at this and that,” he stayed on for six years. He was for a time a member of a motorcycle gang inspired by Dostoievski’s “Young Devils” and the French “poètes maudits” (Rimbaud was van de Wetering’s favorite). The story “Quicksand” in Mangrove Mama describes some of the gang’s antics. He was briefly married to a local artist who taught him “how ideas can be realized into more substantial forms through pottery and sculpture.”

When his father died, van de Wetering returned to Europe, and moved to London, where he followed a course of philosophy lectures at University College in London, “as a ‘reader’, I had no interest in a degree.” He rode an ex-Army Norton motorcycle and spent a year in coffe-shops working his way through a list of philosophical works recommended by professor (later Sir Alfred) A.J. Ayer. He became infatuated with existentialism, but “the resulting dogma that ‘we are condemned to liberty’ seemed too dour.” Ayer suggested that van de Wetering consider Zen Buddhism.

Sojourn in Japan

For two years (1958-1959), van de Wetering studied at the Zen monastery Daitoku-ji in Kyoto, Japan.

Here, for the first time, a glimpse of a possible answer occurred. The Buddhist idea of emptiness, concentrated in the Zen “mu” (nothingness) koan, a meditation subject his teacher made him concentrate on for endless painful hours in a dark hall where police monks beat the unwary, proved to be quite cheerful. No-purpose, happenstance, breaking down of illusionary ego walls, giving in to the only useful desire (the desire to break desire), sublime indifference, moral detachment, non-judgment, and still performing optimally for no reason whatsoever definitely for no reason, were ideas that radiated gloriously from the old abbot’s subtle but forceful being.

Van de Wetering remarks: “Japanese, as I found out, is not easy to get into. It is ranked with Finnish and Hungarian as the world’s most impossible languages. Japanese is liked a cloud, you can't get hold of it. After a year there I could ask all sorts of questions but the answers eluded me. I mastered the phonetic script, 104 scribbles, in little time, but it took almost two years to learn 300 characters and one needs 1850 to read a newspaper. Now I have forgotten it all, but I often gaze at Japanese books (I have read many of the great Japanese novels in translation) and dream about the beautiful script and the wonderful associations.”

Eventually, van de Wetering’s stay in Japan ended — he ran out of money. He found work with a Dutch trading company in South America and the Dutch Caribbean islands. He married again, and in 1963 moved to Australia, where he sold real estate.

Amsterdam Cop

Two years later his wife’s uncle died in Amsterdam, leaving a textile business in disarray. “I went over to get it going again and spent 10 years in the Inner City of Amsterdam. The Dutch Army accused me of violating the conditions of a leave of absence, granted when I left the country at age 19. In order to appease the authorities I volunteered for the Amsterdam Reserve Police, doing uniform duty as a constable, later constable-first-class, and passing sergeant and inspector exams.” Van de Wetering also had the means to indulge his love of motorcycles: “In Holland, when I ran the textile business, I bought a 1943 ‘Liberator’ from U.S. Army stocks, in parts, and had it assembled.” A Harley-Davidson of this vintage — familiar to the Dutch who witnessed the arrival of Allied troops at the end of the Second World War — figures significantly in his first novel.

During this same period, his philosophical curiosity had been aroused again when he met Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche at a Tibetan Buddhist retreat in Scotland. Studies at “The Tail of the Tiger” led in due course to visits to another Buddhist center, “Moon Spring Hermitage,” on the Maine coast. This center was run by a senior American disciple of the (now deceased) Japanese abbot of Daitoku-ji.

Van de Wetering describes the origins of his Amsterdam Cops series:

By that time I was bored with my job and reading the novels of George Simenon, a Belgian/French mystery writer, a multi-millionaire author with some 300 titles to his name. I read both his excellent prose, and that of Sartre, to improve my French to better my company’s export business. It then dawned on me that here was my chance. I could write a series of police novels set in Amsterdam with connections to the foreign places I knew, both in English and Dutch. In America I had been successful with my “Zen” books The Empty Mirror and A Glimpse of Nothingness, the first describing my Japanese stay, the second reporting on a number of visits to an American Zen community. I knew Maine well by then and had bought land there. In 1975 I left Amsterdam, settling in Surry, Maine. The Zen community I intended to join collapsed after a short while but I liked the setting and stayed, boating in summer, writing in winter.

His decision to move to America came at a time when his Amsterdam Cops novels had “taken off internationally.” In the first novels in the series, Lijk in de Haarlemmer Houttuinen (Outsider in Amsterdam), Buitelkruid ( Tumbleweed ), De Gelaarsde Kater (Corpse on the Dike), and Dood van een Marktkoopman ( Death of a Hawker), van de Wetering constructed plots that enabled him to reflect upon a wide range of cultural and social issues affecting Dutch life — from the sexual revolution to attitudes toward Jews and immigrants in late 20th century Dutch society — while taking readers on a tour of the neigborhoods of the city of Amsterdam. Later novels explored other parts of the Netherlands: De Ratelrat (The Rattle-Rat ) is largely set in the rich agricultural province of Friesland, where the stereotypical image of piety and conformity is revealed to be sharply at odds with the reality of corruption, hypocrisy, and deceit.

Insofar as these novels present seemingly accurate details of the progress of a police investigation, van de Wetering respects the conventions of the detective genre, but the novels incorporate jazz improvisation, shamanistic ritual, dreams, and other crime-solving approaches not seen in ordinary police precincts. The interplay between de Gier, Grijpstra, and the commissaris is not the fixed routine of formulaic writing, but an evolving process that reveals van de Wetering’s increasing ability to get beyond the limits of the detective genre.

There are hints of this in Een Dode uit het Oosten ( The Japanese Corpse ), which takes de Gier and the commissaris to Japan to looking into the organized crime roots of a murder in the Netherlands that Grijpstra is investigating. The sections set in Japan are part travelogue and part reflection upon the differences and resemblences between East and West, part thriller and part philosophical digression. Except that the digressions are not digressions but are woven into the fabric of the novel.

Similarly, Het Werkbezoek (“The Working Visit,” published as The Maine Massacre), which in its French translation won the Grand Prix Policier, brings the commissaris and de Gier to the Maine woods in winter, where they solve a series of murders and along the way encounter a very intellectual gang of young nihilists and a rich hermit.

In De Zaak IJsbreker (Hard Rain) van de Wetering pushed even harder at the limits of the genre, for in this novel the three cops act outside the law to solve murders linking a prominent banker to prositution and the drug trade. Suspended from active duty because of baseless charges fabricated by a corrupt bureaucracy, the elderly commissaris encounters an adversary who is in a sense his mirror-image, a man of his age and social class who has chosen to follow the path of crime.

After Hard Rain (1987), van de Wetering published no new novels in the Amsterdam Cops series for more than six years. Van de Wetering notes candidly,

Everything went well but my wife complained about my drinking, mostly in Amsterdam, where I had become a celebrity, and was spending a fair amount of my time. I quit (13 years ago now) but my personality fell apart, I needed to build a new mask, set up new habits. That process took eight years. Instead of writing I was mostly puttering about in an old lobster yacht and doing junk sculpture on my acres of coastal land. Gradually we began to travel. Juanita and I visited Papua New Guinea and Mexico. We discovered Key West and Arizona. By 1993 I began writing again, using a new formula for my Amsterdam Cops. As private detectives, financed by found drug millions, they can finally be amoral.

Van de Wetering clarifies the focus of the new novels and his use of the word amoral by citing a passage from Robert Powell’s epilogue to The Wisdom of Sri Nisargadatta Maharaj (Globe Press/Blue Dove Press, 1992):

The point is that man freed from his fetters is morality personified. Such a man therefore does not need any moralistic injunctions in order to live righteously. Free a man from his bondage and thereafter everything else will take care of itself. On the other hand, man in his unredeemed state cannot possibly live morally, no matter what moral teaching he is given. It is an intrinsic impossibility, for his very foundation is immorality. That is, he lives a lie, a basic contradiction: functioning in all his relationships as the separate entity he believes himself to be, whereas in reality no such separation exists. His every action therefore does violence to other `selves' and other `creatures,' which are only manifestations of the unitary consciousness. So Society had to invent some restraints in order to protect itself from its own worst excesses and thereby maintain some kind of status quo. The resulting arbitrary rules, which vary with place and time and therefore are purely relative, it calls `morality,' and by upholding this man-invented `idea' as the highest good — oftentimes sanctioned by religious `revelation' and scriptures — society has provided man with one more excuse to disregard the quest for liberation or relegate it to a fairly low priority in his scheme of things.

Van de Wetering observes, “Not so the commissaris, he is out there, since his retirement quite free of current morality and dragging his disciples along on weird and wonderful paths. Of course they like being dragged, and will have some escapades of their own, while being guided.”

Just a Corpse at Twilight (1994) was the first of these new novels in the series to be published by Soho Press in New York (also publishers of a uniform edition of the earlier novels in the series). Much of the novel is set along the Maine coast (in the same locale as The Maine Massacre), and it offers a glimpse of the fundamental Dutchness of de Gier and Grijpstra as they trace a murder back to its perpetrator against an American backdrop. Spiritual questions are very much at the forefront.

The most recent books in the series, The Hollow-Eyed Angel (1996) and The Perfidious Parrot (1997), explore misdeeds in New York City and the Caribbean, respectively, that prove to have their roots in the Netherlands. (These books were reviewed in the April 27, 1998, issue of AB together with Judge Dee Plays His Lute, a new story collection.) In the autumn of 1999, Soho Press issued a collection of short stories, The Amsterdam Cops.

Robert van Gulik

Van de Wetering has published a wide variety of books outside the Amsterdam Cops series for which he is best known. Perhaps the most significant of these is Robert van Gulik: His Life, His Work (1987), a profile of his compatriot and fellow mystery author who created the Judge Dee series of novels set in ancient China. “Writers tend to bare some of their usually hidden thoughtlife while the typewriter hums and clacks, so even the respected scholar/diplomat van Gulik may perhaps reveal himself somewhat in his work. . . . Van Gulik thoroughly enjoyed decribing his lieutenants’ adventures. Fantasy is connected to our conscious and subconscious desires. The lieutenants were the more material parts of his favorite hero.” What van de Wetering writes about van Gulik and his connections to Judge Dee, jovial Ma Joong, and introverted Chiao Tai, applies equally well to his own work: the commissaris, de Gier, and Grijpstra.

This brief and complex biography was originally issued by mystery specialist publisher Dennis McMillan in a signed edition limited to 350 copies. The first edition of Robert van Gulik: His Life, His Work is a small, carefully produced hardcover volume with decorated red and gold endpapers and an illustrated dustjacket. The 1998 Soho Press reprint in paperback adds a new introduction by Arthur P. Yin; a hardcover reprint was initially announced but was not produced.

Van de Wetering had earlier been connected with a Dutch reissue of van Gulik’s novels, and in the biography he discussed the reception of the Judge Dee books in the Netherlands, as well as van Gulik’s scholarship and translation of Chinese poetry. He also treats one of van Gulik’s less well-known works, The Given Day, which describes events in the life of Mr. Hendricks, a former colonial official from the Dutch East Indies. In bleak post-war Amsterdam, Hendricks finds himself caught up by accident in the activities of an international drug gang. He also confronts elements from his own past in the course of novel and years after his experiences as a prisoner of the Japanese, Hendricks puzzles out the Zen koan taught to him by his interrogator, and finds a more meaningful understanding of his own existence.

Written in English and first published in an edition privately printed in Malaysia in 1964, van Gulik’s mystery novel was first published in the United States as The Given Day: An Amsterdam Mystery (San Antonio, Texas: Dennis McMillan Publications, 1984), in an edition of 300 copies with an afterword by van de Wetering. (This volume dropped one page of the afterword although the pagination is not interrupted. The 1986 paperback reprint from the same publisher, with a Miami Beach imprint, does not use the subtitle but contains the complete text of the afterword.)

Van de Wetering notes in his afterword, “The Given Day took the Dutch critics by surprise, and most judged harshly. They couldn't understand what the author had been up to and vindictively banished the book to the trash heap. ... I handed out copies of the manuscript to American friends who were mostly disappointed. They wanted another Chinese thrilling tale ... The force of habit. More of the same. Once we see something we can appreciate we ask for endless repeats. Artistic development, however, is subject to change. Picasso painted for years, then tried to bake pots. Gillespie dropped traditional jazz patterns and switched to bop. We do it ourselves; we may continue in a given and successful direction for years on end until a crisis makes us veer off. What we do afterward may not be as easily understandable, or appreciated by others.”

Children’s books by van de Wetering include Little Owl, a discussion of the Buddhist Eightfold Path with black and white illustrations by Marc Brown, and three books featuring the adventures of Hugh Pine, a porcupine, and his friends. He has also translated Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows into Dutch.

Alexandra David-Neel

In the early 1980s, van de Wetering convinced his U.S. publisher, Houghton Mifflin, to issue The Power of Nothingness, his translation of La puissance du néant, one of three novels by Alexandra David-Neel and her adopted son, Lama Albert Arthur Yongden. The novel charts the adventures and frequent distractions of Munpa, loyal servant of a hermit who appears to have been murdered for a jewel he possessed. Van de Wetering remarked in conversation that he had to rewrite certain passages, for David-Neel was curiously prudish and repeatedly turned away from writing about sex. The Power of Nothingness is, in a sense, a Tibetan murder mystery novel, although questions of who was murdered, and by whom, reveal themselves to be inextricably and comically linked with questions of ultimate identity and egolessness. It is without doubt the least well known and appreciated of van de Wetering’s books.

An illustrated mystery novel, Murder by Remote Control, was written as a script outlining the panels of the “comic” strip and “drawn conscientiously by Paul Kirchner, a most talented artist, brother of a Zen monk I got to know in Japan.” It was issued as a lavish volume in the Netherlands in 1984 and as a paperback original in the United States in 1986.

Two other recent story collections of note have been issued by specialty publishers. Mangrove Mama, a volume gathering material from a variety of magazines as well as original stories, was published in 1995 by Dennis McMillan, now located in Tucson, Arizona. McMillan published both a trade edition and a signed edition of 100 copies issued jointly with Wonderly Press of Bar Harbor, Maine. In 1997, Wonderly Press published Judge Dee Plays His Lute in a signed edition (150 copies) as well as in hardcover and trade paperback. Stories in both of these collections feature the Amsterdam Cops.

Van de Wetering is at work upon further adventures of de Gier, Grijpstra, and the commissaris, featuring settings as varied as New Guinea and Arizona. He is also writing a variety of shorter pieces, such as “Ganesh,” a story exploring the consequences of greed for a series on the seven sins planned by his German publishers. Another fine novella, “A Walk in the Park,” recounts an adventure of the commissaris on his own in Maine.

About his reading of other writers, he notes, “In Australia I read the collected works of Arthur Upfield, in America the collected works of Charles Willeford. I also like Jim Thompson and Frederic Exley (not quite birds of the same feather). Lately I have been reading South American literature, I learned Spanish when I worked in Colombia and Peru. I spent years reading Chinese and Japanese literature, always in translation, unfortunately.”

In warm weather, however, van de Wetering spends lots of time boating.

Acknowledgements

This article draws upon an interview with Janwillem van de Wetering conducted over the past several months. I would like to acknowledge his generosity in responding to my questions about his books and his life. Our correspondence has ranged far and wide since I initially wrote to inquire about a mutual interest in Robert van Gulik, about whom he recently noted, “My favorite author is probably Robert van Gulik. I often think I am done with him but then something comes up.” I would also like to acknowledge permission granted by Blue Dove Press of San Diego, California, to reproduce the passage by Robert Powell from The Wisdom of Sri Nisargadatta Maharaj.

A van de Wetering Checklist

The full history of van de Wetering’s publishing career is extremely complex: “I usually write in Dutch, then rewrite in English. The English versions are shorter and I don't get too exuberant with word play. Sometimes the plot lines differ, in some books even the characters differ. I never aim to translate. Many short stories were never written in Dutch. The other way round too.” In matters of pacing and structure, the Dutch text of Het Werkbezoek, for example, differs noticeably from the novel that English-language readers know as The Maine Masacre.

Van de Wetering’s novels have been translated into more than a dozen languages; he is particularly popular in Germany, where a new television series based upon his novels is in the works. Outsider in Amsterdam and The Rattle-Rat were earlier filmed with Rutger Hauer in a starring role.

In the following checklist of books (in English) by Janwillem van de Wetering, novels in the Amsterdam Cops series are marked with an asterisk (*):

1. The Empty Mirror: Experiences in a Japanese Zen Monastery.

London: Routledge, Kegan & Paul, 1973; Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1974.2. A Glimpse of Nothingness: Experiences in an American Zen Community.

London: Routledge, Kegan & Paul, 1975; Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1975.3. Outsider in Amsterdam.

Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1975; London: Heinemann, 1976.*4. Tumbleweed.

Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1976; London: Heinemann, 1976.*5. The Corpse on the Dike.

Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1976; London: Heinemann, 1977.*6. Death of a Hawker.

Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1977; London: Heinemann, 1977.*7. The Japanese Corpse.

Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1977; London: Heinemann, 1977.*HARDBOILED ZEN: JANWILLEM VAN DE WETERING'S THE JAPANESE CORPSE AS BUDDHIST LITERATURE

by Ben Van Overmeire

Though many studies of contemporary Buddhist literature exist, such studies often limit their purview to canonised, 'high-brow' authors. In this article, I read Janwillem van de Wetering's The Japanese Corpse, a detective novel, for how it portrays Zen Buddhism. I show that The Japanese Corpse portrays Zen as non-dualist and amoral: good and bad are arbitrary categories that impede spiritual freedom. Likewise, characters' identities are fluid, not fixed. The novel shows this by insistently associating Zen with sex and violence, and by the use of dramatic motifs. However, the novel also excludes women, particularly Japanese women, from spiritual attainment, instead essentializing them as the sexual objects of the hardboiled detective story. As a matrix of conflicting values, The Japanese Corpse thus turns out to be a case study of Buddhist modernism, and of challenges of detective fiction as world literature.8. The Blond Baboon.

Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1978; London: Heinemann, 1978.*9. The Maine Massacre.

Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1979; London: Heinemann, 1979.*10. Little Owl: An Eighfold Buddhist Admonition.

Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1979.11. Hugh Pine.

Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1980.12. Hugh Pine and The Good Place.

Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1981.13. The Mind-Murders.

Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1981; London: Heinemann, 1981.*14. The Power of Nothingness by Alexandra David-Neel and Lama Yongden.

Translated by Janwillem van de Wetering.

Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1982.15. The Butterfly Hunter.

Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1982; London: Severn House, 1983.16. Bliss and Bluster; or, How to Crack a Nut.

Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1982.

Illustrated by Joe Servello.17. Hugh Pine and Something Else.

Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1983.18. The Streetbird.

New York: Putnam, 1983; London: Gollancz, 1984.*19. The Rattle-Rat.

New York: Pantheon, 1985; London: Gollancz, 1986.*20. Inspector Saito's Small Satori.

New York: Putnam, 1985; London: Gollancz, 1985.21. Murder by Remote Control.

New York: Ballantine Books/Available Press, 1986.

Designed and illustrated by Paul Kirchner.22. Robert Van Gulik: His Life, His Work.

Miami Beach, Florida: Dennis McMillan Publications, 1987; New York: Soho, 1998.23. Hard Rain.

New York: Pantheon, 1986; London: Gollancz, 1987.*24. The Sergeant’s Cat and Other Stories.

New York: Pantheon, 1987; London: Gollancz, 1988.*25. Distant Danger.

New York: Wynwood Press, 1988.

Mystery Writers of America Anthology, edited by Janwillem van de Wetering.26. Seesaw Millions.

New York: Ballantine, 1988; London: Gollancz, 1988.27. Just Another Corpse at Twilight.

New York: Soho, 1994.*28. Mangrove Mama & Other Tropical Tales of Terror.

Tucson, Arizona: Dennis McMillan Publications, 1995.29. The Hollow-Eyed Angel.

New York: Soho, 1996.*30. The Perfidious Parrot.

New York: Soho, 1997.*31. Judge Dee Plays His Lute: A Play and Selected Mystery Stories.

Bar Harbor, Maine: Wonderly Press, 1997.*32. Afterzen.

New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1999.33. Amsterdam Cops.

New York: Soho, 1999.*

[This article was first published in slightly different form, as “The Mystery Novels of Janwillem van de Wetering” in the September 7-14, 1998, issue of AB Bookman's Weekly. All rights reserved.] http://www.avramdavidson.org/wetering.htm

![]()

Janwillem van de Wetering:

PDF: Az üres tükör - Tapasztalatok egy zen kolostorban

Szentendre, 1999

Fordította: Farkas Tünde

A zenkolostorok hétköznapjairól ad a könyv hiteles beszámolót. A történet során kibontakozik a bölcseleti háttér, az ősi meditatív módszer, amely intuitív felismeréshez vezeti a gyakorlót.

Janwillem van de Weteering 26 évesen, felhasználva egy örökség által kapott anyagi lehetőséget, elhatározta, hogy Japánba, Kiotóba utazik. “Hallottam, hogy Kiotó a templomok városa. Szentélyek és kolostorok, titokzatos helyek rejtélyes tartalommal; épületek, amelyekben a bölcsesség ütött tanyát. Én pedig épp ezt kerestem, a bölcsességet, nyugalmat, letisztultságot.”

Sikerül egy zenmestert találnia, aki elfogadja tanítványnak, és a nagy kérdésre, van-e az életnek értelme vagy nincs, ezt feleli: “– Tudnék válaszolni arra, amit kérdeztél. Mégsem válaszolok, mert nem értenéd meg. Figyelj ide. Képzeld el, hogy szomjas vagy, és szeretnél egy csésze teát. Nekem van teám, és öntenék is szívesen, de nincs csészéd. Nem önthetem a teát a markodba, mert megégetlek vele. A földre sem önthetem, mert csak a szőnyeg lesz foltos. Kell, hogy legyen csészéd! Ezt a csészét magad formálod ki önmagadban az itt megtanultak által.”A könyv utószavát Marghescuné Hunor Mária írta:

Majd egy emberöltő telt el azóta, hogy Janwillem van de Wetering belépett a kiotói kolostor kapuján. Az, hogy egy európai fiatalember zenbuddhista szerzetes akar lenni, az ötvenes években szenzációnak számított. Ma elterjedt gyakorlat. Ma már számos japán mester tekinti élethivatásának, hogy a zen szellemét és technikáját a nyugati ember számára tovább adja. Keresztény szerzetesek, filozófusok, valláskutatók, vagy egyszerűen csak kereső fiatalok tanulmányozhatják az évezredes keleti meditációs technikát, és gyakorolhatnak Japán kolostoraiban akár éveken át. Némelyikük időközben már elérte a zentanítói, sőt zenmesteri fokozatot, és hazájában meditációs centrumot működtet.

A zenre jellemző a befogadó ország kultúrájához való alkalmazkodás. Ahogy másfél évezrede az indiai buddhizmus Kínába átkerülve magába szívta a tao filozófiáját és így alkalmazkodott a távol-keleti gondolkodásmódhoz, ugyanígy megváltozott, amikor Koreába, vagy Japánba érkezett. Ugyanez tapasztalható a keresztény tradícióra épülő nyugati formáinál, amerikai és európai változatainál. Minden bizonnyal a magyar zen sem lesz (lehet) egészen azonos sem a japán, sem a németországi zen gyakorlatával.

A lényeg azonban mindenütt ugyanaz: fegyelmezett napirend, amelynek tengelyét a csendes meditáció, a jelen pillanatra történő összpontosítás, a meditatív munka és a tanítóval, a mesterrel fenntartott intenzív kapcsolat jelenti.

A zen nem vallás: életút. Tapasztalatait minden nagy vallás felhasználhatja. Gyakorlása kolostoroktól független, laikusok körében is egyre inkább elterjed. A szekularizáció, a nyugati vallásosság kiüresedése sok „kereső” figyelmét a keleti vallások felé fordítja. Különösen ezek számára jelent nagy segítséget a zen hagyománya, amely nem csak a lelki egyensúly visszaszerzésében és az egocentrizmus legyőzésében segít, de segít abban is, hogy a nyugati ember saját kultúrájának elveszített forrásaihoz visszataláljon.

Részlet a könyvből:

A kolostor kapuja, egy tyúk és egy tésztaárus

Kolostorkapu Kiotóban, Japán szellemi fővárosában. A világi főváros Tokió, Kiotó azonban szent város: olyannyira szent, hogy a második világháborúban még az amerikai bombázók is megkímélték – igaz viszont, hogy cserébe a japánok ígéretet tettek, hogy nem helyeznek el légvédelmi ütegeket a városban. Kiotóban nyolcezer, javarészt buddhista szentély áll. Egy ilyen épület – egy zen kolostor kapuja előtt álltam most. Egyedül voltam, huszonhat esztendős; ruházatom tiszta, frissen mosdottam és borotválkoztam. Szerettem volna szerzetesnek vagy laikus testvérnek jelentkezni. 1958 egyik forró nyári reggele volt. Bőröndömet letettem; nem sok holmit tartalmazott, éppen csak pár ruhadarabot, könyveket és tisztálkodó szereket. A taxi, amely idehozott, már eltűnt. Körös-körül szürkésfehérre meszelt falakat láttam, amelyeket szürke, égetett agyag cserép borított. A falak túloldalán szépen formált, értő kezekkel megnyesett fenyőket pillantottam meg; mögöttük magasodott a szentély teteje, sűrű gerendázattal és enyhe lejtésű síkokkal, amelyek a végükön hirtelen felfelé kunkorodtak.

Még csak pár napja tartózkodtam Japánban. Kobéban szálltam le a holland hajóról, amellyel Afrikából Bombay-n , Szingapúron és Hongkongon át idáig utaztam. Sem kapcsolataim, sem ajánlóleveleim, sem másod-vagy harmadkézbeli ismerőseim nem voltak.

Pénzem azonban volt: ha jól beosztom, akár három évig is elélhetek belőle, sőt néha még valami különlegességre is befizethetek. Nem maradtam Kobéban, hanem azonnal továbbindultam Kiotóba: a vonat egy óra alatt megtette az utat. Láttam Japán zöld szántóföldjeit, amelyek még a hollandiaiaknál is zöldebbek, láttam a bennük magasodó hatalmas reklámtáblákat, amelyeket teljességgel valószerűtlennek éreztem, mert semmit sem értettem meg a szövegükből. Figyeltem az útitársaimat: a férfiak elavult , európaias öltönyökben, amelyeket fehér inggel, de nyakkendő nélkül viseltek, a nők kimonóban. Aprók és alázatosak, de szemük kíváncsian csillog. Bizonyára én is kíváncsian viszonoztam a pillantásukat, mert szájuk elé kapott kézzel kuncogni kezdtek. Rájöttem, hogy itt az én európai átlagmagasságommal valóságos óriásnak számítok – óriás vagyok és kívülálló, egy kisebbség tagja. Egy diákfiú, akinek egyenruhája az első világháborút juttatta eszembe, tört angolsággal megszólított. Megkérdezte, turista vagyok-e. Mondtam, igen. Nagyon szép az országom, mondta ő. Én egyetértettem. A társalgás ezzel el is akadt, egymásra mosolyogtunk. Megkínált cigarettával. Finom volt. Újból nézegetni kezdtem az ablakon.

Hallottam, hogy Kiotó a szentélyek városa. Szentélyek és kolostorok: titokzatos helyek rejtélyes tartalommal: épületek, amelyekben a bölcsesség ütött tanyát. Én pedig épp ezt kerestem: bölcsességet, nyugalmat, letisztultságot. Minden kolostornak van kapuja: ott mehet be az, akit hív a bölcsesség kutatásának vágya – persze, csak ha komolyan és becsületesen gondolja.

Előttem a kapu: klasszikus kínai stílusú faépítmény, gazdag díszítéssel és művészien kialakított cseréptetővel – önmagában is külön kis építmény. Az erős ajtók nyitva álltak.

Az utcáról ismét felnéztem a szentélyre. Nem voltam már egymagamban: lábaimnál egy tyúk kapirgált, szorgalmasan csipegetett a homokban. A távolból mozgó tésztaárust láttam közeledni: a szél felém sodorta a frissen pirított tészta illatát. Az árus fakereplőt forgatott, hangja felvidított volna, ha nyomasztón nem tornyosul elém az a kapu… A kolostorban senki sem várta érkezésemet.

Az előző éjszakát egy kis szállodában töltöttem, amelynek portása beszélt angolul. Amikor egy működő zen-kolostor címét kértem tőle, ahol tanulmányozhatom a zen tanokat, megrökönyödve nézett rám. Azt mondta, ezekre a helyekre nem szabad belépni, menjek el inkább ide meg ide, máshol meg szép kerteket vagy emlékműveket láthatok…még idegenvezetőről is gondoskodik, ha akarom. Elmondta, milyen büszkék a városukra, mennyi érdekességet mutathatnak meg nekem. De hogy zent tanulni! Nem értett meg a jóember. Azt hitte, újságíró vagyok és sztorikra vadászom, s most egy zen mesterrel szeretnék riportot készíteni. Egyszerűen nem érte fel ésszel, hogy én a kolostorban akarok lakni, esetleg magam is szerzetessé válni, és évekig itt maradni. Mégis megadott egy címet, és elmagyarázta, hogyan jutok oda a legegyszerűbben. A leírást mégis túl bonyolultnak találtam, ezért inkább taxit hívtam. És most ott álltam, ahová igyekeztem.

A tésztaárus közelebb jött. Megállította kocsiját, és biztatóan nézett rám. Biccentettem. Azonnal megtöltött egy tálkát tésztával és zöldséggel – pompás illata volt. Egy kis ideig habozott, aztán átnyújtott két evőpálcikát. Nem volt nála kanál. Nem tudtam, mennyibe kerül az étel, hát odatartottam egy marék aprót. Hangosan sziszegve beszívta a levegőt, majd körülbelül húsz pfennignek megfelelő aprót szemezgetett ki a tenyeremből. Amikor észrevette, hogy tudok bánni az evőpálcikákkal, boldogan meghajolt. A tyúk megrohamozott egy földre pottyant tésztaszálat, mintha az igazi élő giliszta volna. Mindketten nevettünk. Nahát, gondoltam magamban, nem is barátságtalanok errefelé az emberek. Próbálkozzunk.

Meghúztam a hatalmas, patinás rézharang zsinórját. A harang a kapugerendán függött. A tésztaárus menekülésszerűen távozott: meghajolt és eltolta a kocsiját. Csak később tudtam meg, hogy ez a szent harang rituális szertartások alkalmával szólal csak meg – a látogatóknak előzetes bejelentkezés nélkül, egyszerűen csak be kell lépni.

Hát ezért a pillanatért szakítottam eddigi életemmel, ezért indultam el a hosszú útra. Ez tehát új életem kezdete, egy új életé, amelyet még csak el sem tudok képzelni. Ünnepélyes pillanat: itt állok, mint hófehér, megíratlan lap; újjászülettem. Boldogan, de egyben feszülten léptem be a kolostorkertbe, ahonnan az épületet immár, hogy nem takarta a fal, teljes pompájában láthattam. Hűvösnek és elutasítónak látszott, mélységes, érinthetetlen békességbe burkolódzott. Mintha maga is a kert szerves része lett volna, a kerté, amelyben nem nőttek virágok – tisztára gereblyézett ösvények vezettek bokrok, kövek, fák között.

És mindenütt moha, sokféle fajta moha, színük a finom szürkétől a mélyzöldig terjedt: nyugodt, békés színek. Ellenben korántsem tűnt békességesnek az a szerzetes, aki közeledett az ösvényen. Komolyan meg kellett erőltetnem magamat, hogy elhiggyem: kortársam. Fura kis figura volt, fatalpú szandálban, amelynek talpára még további fadarabokat erősítettek, úgy hogy az emberke mintegy öt centivel a föld felszíne fölött járt.

Bő fekete öltözékéről, amelyet fehér öv tartott össze, és amely szabadon hagyta a lábszárát szinte a térdéig, akár nőnek is gondolhattam volna – afféle takarítónőnek, vagy mosóasszonynak, aki a súrolást egy pillanatra abbahagyta, és letette a vödröt.

Sebesen közeledett: ruhájának bő ujjai nyugtalanul csapkodtak körülötte. Kopaszra volt nyírva, mosolya pedig, minden zavarban lévő japán végső menedéke, fémesen csillogott, mert ezüstfogai voltak. Néhány lépésnyire tőlem megállt és meghajolt. Meghajlása egészen másfajta volt, mint amit eddig más japánoktól láttam. A japán ember mindig meghajol, ha valakit üdvözöl, de ez a meghajlás szertartásszerű, formális: a hátgerinc meggörbül egy pillanatra, aztán újra kiegyenesedik. Ez a meghajlás azonban ünnepélyes és feszes volt: az emberke mereven a combja mellé szorította a kezét és csípőből, merev felsőtesttel hajolt meg, keze mélyen a térde alá csúszott. Utánoztam, amennyire tőlem telt.

- Jó napot – mondta a szerzetes angolul. – Mit kíván?

- A mesterrel szeretnék beszélni – válaszoltam.

(Janwillem de Wetering: Az üres tükör – Tapasztalatok egy zen kolostorban)