ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

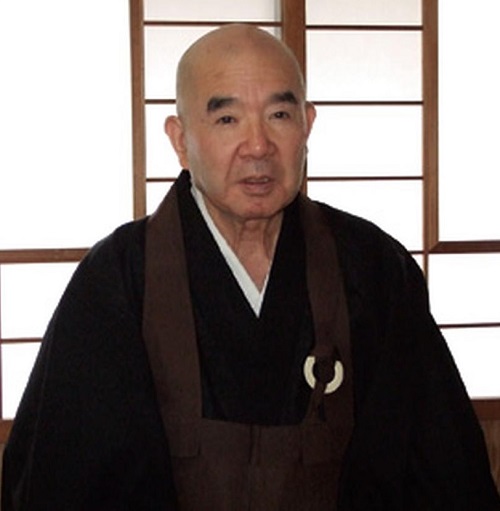

原田雪渓 Harada Sekkei (1926-2020)

Dharma name: 証庵雪渓 Shōan Sekkei

![]()

Sekkei Harada is the abbot of 発心時 Hosshin-ji, a Soto Zen training monastery and temple, in Fukui Prefecture, near the coast of central Japan. He was born in 1926 in Okazaki, near Nagoya, and was ordained at Hosshin-ji in 1951. In 1953, he went to Hamamatsu to practice under Zen Master 井上義衍 Inōe Gien (1894-1981), and received inkashomei (certification of realization) in 1957.

In 1974, he was installed as resident priest and abbot of Hosshin-ji and was formally recognized by the Soto Zen sect as a certified Zen master (shike) in 1976. Since 1982, Harada has traveled abroad frequently, teaching in such countries as Germany, France, the United States, and India. He also leads zazen groups within Japan, in Tokyo and Saitama. From 2003-2005, he was Director of the Soto Zen Buddhism Europe Office located in Milan.

This article is adapted from his book, The Essence of Zen, published by Kodansha International, and from several of his teachings published in Hosshin-ji Newsletter.

*

In Memoriam

Sekkei Harada Roshi (1926-2020)

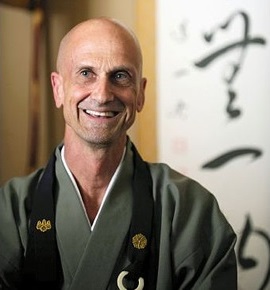

A Tribute to my teacher

by Daigaku Rummé

Harada Sekkei Roshi died on Saturday, June 20, 2020 at the age of 93. He had been in hospice care for more than a year at a small hospital run by one of his students in the town of Obama, Fukui Prefecture. This is the same town where Hosshinji Monastery is located.

Although I lived at Hosshinji Monastery and practiced under Roshi for more than 25 years, I never knew very much about the details of his life. I am now in the process of translating books by his teacher, Inoue Gien Roshi, and recently had to translate Inoue Roshi’s biography. In so doing, I know many more details about Inoue Roshi’s life than I do about Harada Roshi. This says a lot about my teacher. In his interactions with his disciples, and perhaps particularly with his western disciples, he really kept to the straight and narrow matter of realizing the Way.

I had heard indirectly that Roshi had been a young officer in the Japanese Navy and had experienced Japan’s defeat in World War II. I had heard that he was impressed at the end of the war by American soldiers because of their lack of emphasis on hierarchy. I had heard that he had thought of becoming a lawyer, but it’s clear that he was ordained a Soto monk in 1951 by Harada Sessui Roshi. He began his practice at Hosshinji Monastery but became disappointed with the teaching he was receiving there; Roshi went to practice in Hamamatsu with Inoue Roshi in 1953. I’m quite sure he attained the Way and was a fully realized person by the age of 31. But all these details are vague.

He often spoke about the question Inoue Roshi had asked him one day while they were weeding the temple garden. “What are you doing now, Sekkei-san?” Inoue Roshi had asked him. “Surely, he can see what I’m doing,” Harada Roshi thought. But then, the doubt arose, “There must be a reason he’s asking me this question. I’ve got to be able to answer it.” This doubt pushed him to devote himself to being able to answer this question, which he finally was able to do. After much hardship and suffering, he finally forgot himself and realized the Way. Inoue Roshi acknowledged him as his successor with the following poem:

A cow has entered the mountains

And had plenty of water to drink

And grass to eat.

That cow now leaves the mountains

Touching the East, touching the West.

I do know that he had made it his life’s work to become abbot of Hosshinji Monastery, the place where he had been ordained. He was married to Korin, his teacher’s niece. Together, they lived at Shimpukuji, a small Soto temple about five miles away from Hosshinji. I remember hearing that Roshi was Ino (head monk) for some years at Hosshinji. In 1974, he was installed as abbot of Hosshinji. From that time on, he and his wife did not live together until much later (about 2013) when he became ill and they moved into Kakushoken, the small hermitage located outside the main gate at Hosshinji.

Roshi was always hospitable to westerners who wanted to learn about Zen and do Zen practice. He never learned to speak English, however, which forced a certain number of the western monks to study Japanese. I can’t remember the exact number, but I’m quite sure he ordained at least twenty westerners, both men and women.

I can’t remember exactly when I first met him, although it would have probably been around June 1976. Guren Martin, who I knew from Kyoto, had gone to live at Hosshinji in 1975, and I went up to visit him and see Hosshinji. I do remember my first meeting with Harada Roshi at that time. I returned to Hosshinji for part of the October 1976 sesshin and received permission to stay there, which I did on Nov. 12, 1976.

Roshi was always a generous man, but he was also strict. There were several contrasting sides to him. In a real way, he could be unpredictable. He could get angry, but the anger dissipated quickly. He could be joyful, and when he laughed, it was complete.

Many memories come back to me, but I don’t want to go on at length now. The main thing I want to say is that Roshi was a mountain of the Way. I knew from early on that he was a special person. He was always completely present, ready to do what needed to be done. He was without human sentiment and doubt. He was always clear, fair, kind, and strict. In Japan, Zen monastic life is known for being a strict way of life. He once said that strictness is only a matter of whether a person has attained the Way or not. For him, that was the standard and it was his job to point the direction for those who were seeking it.

Daigaku Rummé

Confluence Zen Center, St. Louis

June 24, 2020

Unfathomable Depths: drawing wisdom for today from a classical Zen poem

Translated by Daigaku Rummé and

Heiko Narrog

Wisdom Publications, 2014

同安常察 Tong'an Changcha [active 10th century]:

「十玄談」 Shi xuantan 'Ten Verses of Unfathomable Depth'

Ten poems (“mystery discussions”) in the early Song master Tong'an Changcha's 同安常察 Shi xuantan 十玄談. Each discussion consists of a seven-syllable verse, the first entitled “mind seal” (xinyin 心印). Jingde chuandeng lu 景德傳燈錄 (T2076.51.455a27-b2).

Unfathomable Depths presents a concise treatment of Soto theory and practice, while delivering approachableadvice from Sekkei Harada, one of Zen's most esteemed teachers. Rooting himself in Tong'an Changcha's classical and enigmatic poem, “Ten Verses of Unfathomable Depth,” Harada intimately speaks to the world of Zen today, answering some of our most pressing questions:

What is the true nature and function of Dharma transmission

How do I appropriately practice with koans?

How do I understand the “just sitting” of Soto Zen?

PDF Preview pp. 1-61.

Table of Contents

Translators' Preface

Ten Verses of Unfathomable Depth

I. Introduction

Heiko Narrog & Hongliang Gu

The Text

The Author

The Title and an Overview of the Text

Tong'an Changcha's Verses and Sekkei Harada's Dharma Lectures

II. Commentary on the Ten Verses

Prologue: Master Tong'an and the Verses of Unfathomable Depth

1. The Mind Seal

2. The Mind of the Enlightened Ones

3. The Unfathomable Function

4. The Transcendent within Dust and Dirt

5. The Buddhist Teaching

6. The Song of Returning Home

7. The Song of Not Returning Home

8. The Revolving Function

9. Changing Ranks

10. Before the Rank of the Absolute

Appendix I: Chinese Edition of the Ten Verses

Appendix II: Contemporary Comments on the Ten Verses

Table 1: List of Personal Names

Table 2: List of Texts Cited

PDF: The Essence of Zen: The Teachings of Sekkei Harada

Translated by Daigaku Rummé

Wisdom Publications, 2008

Table of Contents

Translator's Preface ix

Introduction 1Part I. Dogen's Fukan-Zazengi and Commentary

The Fukan-Zazengi: A Universal Recommendation for Zazen 7

An Explanation of the Title 11

You Are Already Within the Way 13

Giving Up the Ego-Self 19

How to Sit in Zazen 25Part II. Being Thoroughly Familiar with the True Self

In the Whole Universe, There Is Only You 43

You are Both Zen and the Way 43

Your Reality Is Zen 44

Do Not Forget Your True Self 45

Three Principal Teachings 46

Nothing Is Better Than Something Good 50

Nansen Cuts the Cat 51

The Deluding Passions Are Enlightenment 53

Throwing Yourself into Zazen 54

Hyakujo's Wild Fox 55

The Daily Practice of Zen 59

Continuing with Perseverance 61

Sitting in Zazen 62

Putting an End to the Discriminating Mind 64

"Done, Done, Finally It Is Done!" 65

Being One with the Questioning Mind 67

The Way Is One 68Part III. Awakening to the True Self

What Is Sesshin? 73

Kyogen's QuestioningMind 75

What Is "This Thing"? 76

"Everyday Mind Is the Way" 78

Accepting Your Condition Now 81

Are You Awake? 83

Shakyamuni Buddha's Practice 84

The Deluding Attachment to the Ego-Self 85

All Things Exist Within the Six Sense Functions 86

What Is the Teaching of the Buddhadharma? 87

In Japan Only the Form of the Dharma Remains 88

Self-Taught Zen vs. Zen That Is in Accordance with the Dharma 89

Good and Evil Is Time; Time Is Not Good or Evil 92

The Wind Blows Everywhere 95

On Emptiness 96

The Ten Realms 97

The One Arrow of Sekkyo 102

Becoming Your Own Master 103

"No Dependence on Words and Letters" and "A Special Transmission Outside the Teachings" 104

Stealing the Farmer's Cow, Snatching the Beggar's Bowl 104

Exaggerating the Importance of Doctrinal Study 106

Verification for Oneself and Certification by a Master 107

The Certification of True Peace of Mind 108

To Study the Way Is to Study the Self 109

Letting Go of Oneness 110

The First Step on the Way 111

The Problem with Shikantaza 112

The Problem with Koan Zen 113

Using the Form of Zen as an Expedient 114

The Condition Right Now 116

What Is Consciousness? 117

The Light of the Dharma, the Light within Yourself 119

Awakening to the Chaos within You 120

The Law of Cause and Effect 121Part IV. Elements in the Practice of Zen

The Functions of the Body, Speech, and Thought 125

The Problem of the Self That Knows 125

Three Essential Elements of Zazen Practice 127

Throwing Away Your Standards 130

Great Diligence 130

"What Is the Way" 131

The Sickness of Being Attached to Emptiness 133

The Nature of Zen 135

Repentance 138

Zen and the Precepts Are One 141

Mind Cannot Be Grasped 143

The Enlightenment of Gensha 146

Zen within Movement, Zen within Stillness 148

Being Attached to the Ego-Self 150

Liberation Is Leaving the Dharma As-It-Is 153

Dead or Alive? 154Afterword 157

Zen Masters and Monks Appearing in the Text 161

Glossary 163

PDF: L'Essence du Zen - Entretiens sur le Dharma à l'intention des Occidentaux

by Sekkei Harada Roshi

Traduit de l’anglais par Monto de Paco et Laurie Small

2013

Being Thoroughly Familiar with the True Self

Excerpts from The Essence of Zen: The Teachings of Sekkei Harada

http://wearebuddhamind.blogspot.hu/2008/12/being-thoroughly-familiar-with-true.html

IN THE WHOLE UNIVERSE, THERE IS ONLY YOU

In what way can you become familiar or intimate with your true self? Zen, the Dharma, and the Way point the direction. Consequently, Zen, zazen, and the Way are all means to take us to the world of the Dharma. Many people, though, are greatly mistaken on this point. They think it is sufficient simply to do zazen, or simply to seek the Way, and this is the end of it for them. I would like to explain why this type of thinking is mistaken.

The present population of the earth is said to be almost six billion, or even more. This means that each of us is one of these six billion people. Each of us is irreplaceable; we each have our individual existence. This is something that must be clearly discerned. First, we must see our own essential Self, and then it is necessary to make sure that we live our lives with our feet firmly on the ground. We are each one part of six billion people, and we must ascertain that we are truly the only person in the whole universe, someone who doesn't need to rely on Buddha, the Dharma, or the Sangha. This is the first step in being familiar or intimate with the true Self.

YOU ARE BOTH ZEN AND THE WAY

I would like to tell you a story from China. You may be familiar with the name of Joshu, who was a priest long ago. One day a monk asked him, "I am just a beginner in the practice of Zen. Please teach me how to do zazen." Joshu said, "Have you eaten breakfast? .... Yes," replied the monk, "I've had plenty for breakfast." Joshu said, "That's fine. Then wash your bowl and put it away." At that point the monk, who had resolved to seek the Dharma was just beginning the practice of zazen, said "I understand. Now I realize the direction of practice." So he went off happily.

There is an important point in the story for those of us who practice. We tend to think of our eating bowls as things that are outside of us. Yet Joshu said, "Wash your bowl and put it away." What does the bowl signify? You yourself. Each one of you must clean yourself thoroughly and then bring the matter of the ego-self to a conclusion. If Joshu's words are not understood in this way, a great mistake will arise. We perceive Zen, the Dharma, and the Way to be outside of ourselves. But it is a serious error to create a distance between yourself and these things in this manner. If you make a separation between yourself and what you are looking for, no matter how much effort you make to lessen that distance, that effort will be in vain.

It is a mistake to look for something that is far off in the distance. The Dharma is something that is everywhere at any time.

YOUR REALITY IS ZEN

I come from Japan, but Zen, the Dharma, and the Way do not exist solely in Japan. Zen, the Dharma, and the Way--these are things that cannot be exported. Since they cannot be exported, they cannot be imported. Consequently, that which has been imported from India, China, or Korea in not Zen, the Dharma, or the Way; these are each of you--your reality as-it-is. The reason I say this is so that you will understand that reality as-it-is is Zen, the Dharma, and the Way.

But if you do not "walk the Way," it will never be possible to reach your destination. The first human being to awaken and realize he himself was the Way was Shakyamuni Buddha. It was not the case, however, that he grasped something new. For those who believe in the Way of the Buddha and aspire to practice Zen, it is only natural that they will practice in the manner taught by Shakyamuni Buddha and the enlightened ones of India, China, and Japan who transmitted the Dharma.

If you clearly and certainly walk the Way, you will awaken to yourself. However, if you create a distance between yourself and Zen, the Dharma, and the Way, even if you walk the Way, I think you'll always feel great anxiety as to whether you will be able to truly realize the Way or not.

Since the Way and Zen is your condition as-it-is, there will definitely come a time when you realize, "Ah! So that's how it is!" There is no doubt about this. It will take longer for some of you to reach this point than others, but nevertheless you will definitely realize it. For some people it has taken thirty years to realize themselves, it took Shakyamuni six years. Others have realized in a single day. It varies from person to person. However, it will undoubtedly happen.

Shakyamuni Buddha gave the following example to indicate how certain this is: If you hold a stick in your hand and aim for the ground below you, no matter which way you strike the ground, it is impossible to miss it. In the same way, it is impossible not to come to an understanding of the true Self if you seek the Dharma and Zen.

DO NOT FORGET YOUR TRUE SELF

There is a story about a priest named Zuigan. Each morning, on awakening, he would always address himself, saying, "Master, master!" which could also be translated as "True Self, true Self!" He would ask himself, "Master, are you awake?" He would answer, "Yes, yes." And then he would say, "Don't be fooled by others." Whereupon he would answer, "No, no." This was his practice.

We are apt to forget our true Self. "To forget" means that we are always out traveling and away from home and so our home--or body--is vacant. We will be in a condition where we always think that sometime in the future, eventually, we must return home.

You may be familiar with the great thirteenth-century Zen master, Master Dogen. At first he traveled to Ghina in search of the Way. This was a condition in which his true Self was absent. But then he met Tendo Nyojo, another Zen master, and was able to "cast off body and mind." How did he express what he had attained?

The eyes are horizontal

The nose is vertical.

I won't be fooled by others.

The Buddhadharma does not exist in the least.

In another story, old Master Joshu said, "Before I knew that the Way is myself, I was used by time. But after I realized that the Way is myself, I was no longer used by time. Now I am able to live using time." For Joshu, hot was still hot, cold was still cold, and pain was still pain. He was still the same person--and yet depending on whether Joshu realized his true nature or not, he lived being used by things or he lived being able to use things.

The fact is that each of you possesses the same power as Joshu. By becoming intimate with Zen, you will understand how it is possible to find and master this power. When you do, each of you will be Joshu, Dogen, and Shakyamuni Buddha.

THREE PRINCIPAL TEACHINGS

In Buddhism there are three principal teachings: all things are impermanent; all things are without self-nature; and all things dwell in the peace and quiet of Nirvana. The first of these--all things are impermanent means that there is no condition that is fixed or determined for any length of time. It is not a matter of there being one thing that is undergoing change. It means that things---including yourself--are always changing and are without a center or an essence. As human beings we are always perceiving through the senses; which means that we are cognizant or aware of things. We can only perceive past and future. All anxieties--the opposite of peace of mind--as well as agitation, restlessness, and haste, arise from either the past or the future.

As I said earlier, the present moment is a condition where there is absolutely no separation between yourself and things. This is not to say, though, that there exists such a thing as the present moment. The condition we refer to as "now" is one where there is truly no.gap between yourself and other things. When you don't have peace of mind, this means that you are in a condition in which you are constantly aware of a distance between yourself and other things. In our present life, regardless of whether we know it or not, we are one with things. This is what is meant by the challenging expression "all things are impermanent."

No one remembers the time when they were born, the time they emerged from their mother's womb. In the same way, there is no one who knows their own death, thinking "I've just died." We know neither our birth nor our death. We first become aware of ourselves at the age of three or four. If we live to the age 0f eighty, during the intervening years we experience many things that are good and bad. There is gain and loss, there is this thing and that, but whose life is it.~ This world of perception and cognition--what we usually think of as the way human life must be or should be--this is all the life of the ego. Zen is the means that can help you discover the true nature of the ego.

When people are asked to give proof that they are living, they often cite the fact that they can see and hear and feel things. But this is not proof that you are living. It is merely a description of living. You perceive your self, the ego, "me," and then simply describe your present condition by saying that because you can see and hear and feel you are living. Someone who is dead cannot, obviously, describe what the condition of death is like. The reason is that it is already their reality. There is a problem of how to demonstrate the reality of living without description.

Even if you are aware of minute changes within the flux of events, you must understand that it is the ego that knows it and n6t the true Self. This means that with regard to our whole life, as long as the thing we call "me" does not stop intervening, it is not possible to lead a life that is truly free and peaceful. You already are free, but since you want freedom, you lose it. Consequently, it is necessary to free yourself from thinking that things must be this way or that way. This too is the meaning of the first teaching, "all things are impermanent."

The second teaching states "All things are without self-nature." As all things are selfless, this means there is no possibility of grasping on to something as your unchanging essence. For example, imagine it is now 8:00 in the evening. Let us say we go to bed at 10:00 and drift off to sleep without knowing it. While sleeping, who knows that they are asleep? Most likely, there is no one who is aware that they are fast asleep. In the same wa~, when we awake, it is not possible to be aware of awakening. All you can do is, by perceiving "this thing" (the body), say you are "awakened." But who is it, through perceiving "this thing," that calls it "you"?

No one can think two thoughts at the same time. If you were asked to think a good thought and a bad thought at the same time, it would not be possible. Have you ever considered why it is not possible to think two things simultaneously? Whether you think about this or not, you are yourself and you are living your own life. In fact, it is not possible to think of yourself. This means that it is not good to insert your own egoistic opinions. If the ego-self intervenes, it means that inevitably you will see things by comparing them. Zen practice is the practice of letting go of that intervention of the ego-self.

The third teaching is that "all things dwell in the peace and quiet of Nirvana." As I said at the beginning, Nirvana, or true peace of mind, is something that we must not seek elsewhere As long as you seek it elsewhere, you will never be free of feelings of satisfaction or anxiety. If we open our eyes, even when seeing something for the first time, we can clearly see all of it. If you hear something for the first time, you can hear it perfectly. You are endowed with the free functioning of the senses. This means that no matter what you see or hear, you assimilate all of it. You have the power to digest things in this way.

In a life where there is no separation, there is neither peace of mind nor anxiety. When there is peace of mind, there is also anxiety. In a world of the true Dharma, there is neither peace of mind nor anxiety. Having said that, there may be some people who wonder, "Then why is it necessary to practice.~" But really try living "now." There is no room for thoughts like peace of mind and anxiety to enter in. In this way, no matter how insignificant or important something may be, whether for yourself or for someone else, forgetting yourself and immersing yourself wholeheartedly in your work and making an effort, that is the life of Zen. It is the life of the Way.

People often speak of doing something for this or that purpose but in Zen we do not live our lives for this or that purpose. Even if we are doing something for ourselves or for someone else, the life of Zen is to forget all that comes before and after and really do each deed for the purpose of the deed itself. Wholeheartedly applying yourself to the task at hand, exhausting yourself in each activity, that is the life of Zen. Consequently, I would like you not to understand Zen, the Buddhadharma, or the Way by means of your intellect or your education.

Although I have just said that all of our life is Zen, the Dharma, and the Way, actually these things do not exist.

NOTHING IS BETTER

THAN SOMETHING GOOD

In everyday life, we often hear people say, "Now I can really believe it." But as long as you are satisfied with "really believing," it means that there is still belief. You must forget belief. It is the same with fact and reality. If you think something is true or real, it means you perceive "real" or "true," and there remains a gap between you and "real" or "true." The life of someone who has realized the true Dharma is one where there is r~o reality. In other words, it is to dwell peacefully in the world now.

There is a Chinese proverb that says: "Better than something good is nothing." Zazen is a wonderful thing. But even though it's wonderful, nothing is better. The reason is that something good is a condition on the way to the ultimate. We do not know if it will become better or worse. The key to zazen is to "grind up" zazen by means of the practice of zazen. If you follow through with this, then no matter what you are doing or where, each activity can be called Zen. When zazen is finally completely ground up and disappears, then for the first time everything is truly the Way, Zen, the Dharma. This is what is called "everyday mind."

Finally, I would like you not to simply understand Zen or the Buddhadharma conceptually. It is fine to investigate what others have said or written in books. But to say, "I've understood something that I didn't understand before," that is not Zen practice.

NANSEN CUTS THE CAT

Consider this koan from the Book of Serenity (Shoyoroku), "Nansen Cuts the Cat":

There were about 5oo monks training under Nansen. The monks slept in one hall that was divided into east and west. One day the monks were fighting over a cat. Seeing this, Nansen picked up the cat and said, "If you can say anything, I won't cut it in two." No one spoke, so Nansen cut it.

Later, Nansen told Joshu what had happened. Joshu immediately took off his sandals, put them on his head, and walked out. Nansen said, "If you had been there, you would have saved the cat."

This particular koan originated in China 1,200 years ago but it is not just a story. I would now like to explain why.

Nansen is the abbreviated name of Nansen Fugan, a famous priest of Tang China. Nansen cut a cat in two, and this cat is the central problem of this koan. Three people or groups of people appear: the monks who are asked the question, Nansen, and Joshu--plus the cat. Each of you are now Nansen, you are now the monks being asked the question, you are now Joshu, and you are now the cat.

An argument began among some of the monks concerning the cat. "Does the cat have buddha:nature or not?" "In the future, will it become a buddha?" "Can it do zazen?" They argued about the Dharma and Zen just as we do every day. While the monks were arguing, Nansen appeared and picked up the cat by the scruff of the neck. He said to the monks, "If you can say something about this cat, you will save it. If you can't say anything, I'll cut the cat in two."

In your heart you wonder, "What is Zen? What is the Way?" You have been practicing zazen for a long time, but will you really be able to attain the wonderful results related by the buddhas and enlightened ones? These were the questions the cat represented. If you become the cat, then you will clearly understand. Or if you become the monks, I think you will also understand. Nansen, by picking up the cat by the neck, symbolically demonstrates to each of us the need to get a grip on the questioning mind. "How will you resolve this?" You must understand Nansen's question this way. It is as if Nansen appears in front of you and asks, "How will you deal with this matter?" For those of you who have this questioning, inquiring mind, this questioning mind is the cat. For those of you who practice shikan-taza, this shikantaza is the cat.

In this koan, you must be able to give the answer immediately, "Say it now." Understand this is your problem. "Out with it!" Can you clearly awaken to your essential self? That is the meaning of this case. None of the monks could answer Nansen--how would you answer? Have you been able to get a firm grip on the cat or not? Perhaps, while you are sitting zazen, the inquiring mind is clear, and perhaps you understand clearly how to practice shikantaza. But when you are eating or doing work, doesn't the cat get away?

The Way as well as Zen must be everywhere at any time. If Zen or Zen practice exists only when you think of it, then you will never be able to resolve the problem of the cat. Whatever we see or hear or feel, everything we experience is buddha-nature. In the case I have related, it is written that Nansen cut the cat in two. But is it possible to cut buddha-nature in two? Please consider this. If you are "just" sitting, you will get stuck in "just." The reason I am presenting this case is so that you can check and see to what extent you are "just" sitting. How do you see the cat? I am waiting to hear your answer.

None of the monks could answer Nansen, so he finally cut the cat in two. Joshu was out working when Nansen cut the cat, but when he returned, Nansen said to him, "Today a problem arose concerning a cat, but none of the monks could give an answer, so I cut the cat in two. How would you have answered?" On hearing this, Joshu put the sandals he was wearing on his head and went outside without saying anything. Whereupon Nansen said, "If you had been there, it would have not been necessary to cut the cat." The problem this koan represents for us, then, is how we will answer so that the cat is not cut. I would like you to be Nansen, the monks who were asked the question, Joshu, and the cat. While you are in this condition, thoroughly think through this case.

All of the buddhas and enlightened ones who appear in collections of Zen sayings and records are you. They are speaking about each one of us. This story comes to us across twelve centuries, but if each of you save the cat, then Nansen as well as ]oshu will be resurrected.

THE DELUDING PASSIONS

ARE ENLIGHTENMENT

Within our minds, there is a cat called "greed." There is also a cat named "anger" and another cat called "folly" or "ignorance." In Buddhism, we call these the three deluding passions. These passions or desires are the source of all our suffering. However, if there was no greed, we would not be able to do zazen. Without anger, the determination and enthusiasm not to lose out or be beaten would not arise. Without ignorance, there would be no reflection or introspection. For these reasons, I would like you to understand that greed, anger, and ignorance are also other names for buddha-nature. It is only because we are used by greed, anger, and ignorance that we have come to think of them as being bad.

Shakyamuni Buddha also said that the deluding passions are themselves enlightenment.

If you sit in shikantaza and let whatever thoughts appear and take no notice of them and do not deal with them, then they will definitely turn into enlightenment. You may recall the expression "everyday mind is the Way." Anger, ignorance, greed, as well as all kinds of anxiety, impatience, and irritation, exist within the "everyday mind." This is called "everyday mind as-it-is is the Way." I would like you to realize that it is a mistake, then, to throw away something bad that is inside us. In Buddhism, however, everything is buddha-nature, so there is nothing to throw away. The problem lies within your thoughts, or how you think. Inevitably you cannot accept your thoughts, so you create a distance between you and them. But, as I often say, zazen is the way to verify that you and your thoughts are one. We practice so we can confirm this.

THROWING YOURSELF INTO ZAZEN

I will digress for a moment to speak of a man named Toyohiro Akiyama. He is a reporter working for TBS, a Japanese television company. Some time ago, he was sent into space on a Soviet rocket. Later, when he returned to Earth, he was asked, "While you were in space, did you have any kind of religious experience? Have you returned with any philosophical impressions?" Akiyama replied, "I was already so preoccupied with my affairs here on Earth that I experienced absolutely nothing different on venturing into space."

As I always say, as long as you do not truly bring a resolution to the ego-self, no matter how wonderful a universe you travel to or whichever world of God or Buddha you may reach, there will be no change. Throw yourselves into zazen and really forget your own thoughts. With this kind of practice, you will certainly be able to meet your true Self. Please believe until belief is no longer necessary.

HYAKUJO'S WILD FOX

Consider this koan:

Whenever Master Hyakujo gave a teisho, or Dharma talk, an old man always came to join the monks and listen to the teaching. When the monks left, the old man would also leave. One day the old man stayed behind. Hyakuio asked him, "Who are you who stands before me now.?' The old man said, "I am not a human being. In those days of the Ashy Buddha, I used to live on this mountain. One day a monk asked me, 'Is an enlightened person also subject to causality or not?" I said 'No, he is not.' Since then I have lived the life of a wild fox for five hundred lifetimes. I now beg you to say a few words on my behalf to release me from my life as a fox. For that reason I ask you, 'Is an enlightened person also subject to causality or not?'" Hyakuio said, "Such a person is not blind to causality." No sooner had the old man heard these words than he became greatly enlightened.

If you could not quite become completely one with Nansen's cat, perhaps you can become one with Hyakuio's fox. This case concerns cause and effect and appears in every collection of Zen koans. It is regarded as very difficult. The particular problem dealt with is whether a person who is enlightened and "finished" with practice is subject to the principle of cause and effect or not.

First of all, let me speak about the principle of cause and effect. It is said that if you wish to know a past cause, then look at the present effect, the present result. There is always a continuum of past, present, past, present. We cannot say that the past is only something that happened long, long ago--it also is five minutes ago, or even a single moment. Your condition now is inevitably attributable to past causes. The present circumstance also becomes the cause of some future outcome.

With regard to breathing, each breath is new. So too with thoughts. When one idea or thought arises, that is birth. When one idea or thought vanishes, that is death. Always there is a constant repetition of birth and death. This repetition continues through past, present, and future.

We are in the habit of perceiving "this thing" (this body) as "me." The reason for this is that from birth we have come to believe that things exist. In fact, though, they do not~but we usually cannot accept this. This is the meaning of "all things have no self-nature." If there is a center, essence, or permanent self-nature that is perceived, this is a delusion. Similarly we make errors about time; we can only perceive time either through the past, which has already gone, or by the future, which has not yet come.

Consider the method of zazen in which we practice counting breaths. If you reach "two," for example, then "two" is everything. There i~s no "one" or "three." "Two" is all. At that point, you should have truly forgotten yourself and cast off body and mind.

Nonetheless, we perceive that something that does not exist does exist. This is the ego, which inevitably becomes the center of what we perceive. For this reason we are in the habit of seeing things and comparing them in terms of good and bad. Consequently, it is easy for people to think that if all bad things could be eliminated, only good things would remain. Nevertheless, good and bad exist only in contrast to each other. If all bad things were to disappear, then it stands to reason that there would no longer be any good things. If one half of a duality were not to exist, its opposite would also not exist. Please understand this clearly as we explore the principle that cause and effect are one.

In the teaching of Buddhism, everything is taught from the standpoint of the result. This means that for those people who have not yet reached the final result, it is not possible for them to say that they either understand or do not understand simply by looking at the teachings of Shakyamuni Buddha or of the enlightened ones who have transmitted the Dharma.

The "dharma" of Buddhadharma means a natural principle or law. Every aspect of our life is the Dharma. There is the Dharma of bad and the Dharma of good. There is als9 the Dharma of understanding and the Dharma of misunderstanding. Moreover, these two are not in opposition. Our condition now is one that is already separate from good and bad, enlightenment and delusion. We are always peacefully dwelling in a condition where there is only the result itself. Yet, in order to awaken to the condition, it is necessary, by means of Zen, to let go of our dualistic viewpoint of comparing good and bad.

Results unavoidably correspond with causes. There should be no feelings of surprise or disappointment. If our efforts result in failure, it is only reasonable to be content with that result. The same applies to successful results. If there is a successful outcome, the requirements for this success were present, so there is nothing to be happy about. Similarly, do not feel disappointed in failure. Nevertheless, people can be seen to be selfish because when we have some success, we are naturally pleased with that success, and when we encounter some failure, by comparison we are not happy.

Returning to the case about Priest Hyakujo: Why then, on answering "does not fall under the principle of cause and effect" did the priest become a fox? And why on hearing "not blind to cause and effect" did the old man again become a human being and realize great enlightenment? What is the degree of difference between "not falling under cause and effect" and "not being blind to cause and effect"? Investigate this problem; generate this inquiring mind.

The point of this case is whether the wild fox is at peace with being a wild fox. If the fox could truly be one with being a fox, then it would not want to become human. To be a fox would be enough. The state of being truly satisfied as a fox is what we call being "a buddha." On the other hand, a human being who is not satisfied with being human and who constantly looking for something else is seeking to be a buddha; this state we call being "a wild fox." This is a very difficult problem.

In Buddhism, we speak of transmigration though the six realms. These realms are the six worlds of delusion: heaven, human beings, hell, hungry ghosts, animals, and fighting devils (asuras). As 10rig as we are deluded, we can never live peacefully as human beings. If you cannot be at ease with your present situation, you will forever be seeking something else. This is a condition where you will go around and around, migrating through the six realms, never feeling settled. Essentially, though, regardless of whether we are a being in hell, a human being, or a being in heaven, we must be able to exist peacefully in these respective worlds.

In Zen, we have the expression "unblemished" or "undefiled." The Japanese word for this, fuzenna, literally means "not-dyed-dirty" in other words, "untainted." Many people understand this to mean that if you practice and achieve a certain strength or power through that practice, no matter which world you go to, you will not be dyed the color of, or be sullied by, that world. But this is a great mistake. "Unblemished" or "undefiled" means to be completely dyed that color. If you go into the color red, then you are completely dyed red. If you enter something white, then you completely become the color white.

In the Rinzai Zen sect, the expression "be master of yourself wherever you are;' is often used. If this expression is misunderstood, it will be misunderstood in the same way as "unblemished." If you cannot be truly at one with the world you have in, you will always see other worlds as being beautiful and wonderful. The words "not falling under the principle of cause and effect" and "not being blind to cause and effect" are concerned with this condition of not being settled, of not accepting your situation.

The main purpose of practice is to bring an end to the seeking mind and to live accepting your present circumstances. It is important that you sit in zazen and are content with the result. As you sit, inevitably the thought arises that somehow or other you should be able to sit better. This is a fact. But sit without thinking that because you cannot sit well, you want somehow to sit better, If you cannot sit well, then accept it and leave it that way. If you are not settled, then accept it and leave it that way. I would like you to make the effort to live peacefully in whatever condition you are in.

To be truly what you are without being jealous of someone else is what we call Buddha. However, if a person cannot peacefully accept being a person, he or she will always want to be a buddha, to experience enlightenment. We liken this condition of trying to seek peace of mind to that of a fox. Think this through carefully as you continue with your practice.

In Japan, a fox is regarded as an animal that tricks people. Please practice steadfastly and confidently without being tricked or misled. If a fox is tricked by a fox and continues being tricked, that is all right, but it isn't good to set up the ego-self with the attitude that you cannot be tricked.

THE DAILY PRACTICE OF ZEN

Zazen can broadly be divided in two: Zen within activity and Zen within stillness. Zen within activity embraces the other activities in our life, such as our work and so forth. Zen within stillness is what we do in the zendo, the meditation hall.

I would like to speak practically about how you can continue with Zen outside of the meditation hall, outside of retreat. Everyday life itself is Zen. As I have already said many times, drinking coffee, eating toast, washing your face, taking a bath, these are all Zen even though we do not label them Zen. I would like you to be clear about this. Consequently, there is absolutely no need to choose between activities that are Zen and those that are not. Believe this firmly and have unshakable confidence in it. Then let go of this faith. This is the way I would like you to act, but in practice this is not easy. It is a mistake for you to incorporate into your life things you have learned about Zen through books or by listening to others. This also includes the Zen practice you have done up until now.

There is an expression in Zen "to put another head on top of the one you already have." This is a mistake. It really is not possible, and I want you to take great care not to make this mistake. Even though I say this, I am sure you will live and experience many things, learning by trial and error. You make an effort to build up your practice, but then you become lax and it falls apart. Again you make an effort to build up your practice, but again you become lax and it falls apart. It is important not to give up. While living your everyday life, I ask you once again not to adopt or bring Zen into that life. Apart from those times when you are sitting quietly, I would like you to forget completely about Zen.

I also have some comments about formal sitting, Zen within stillness. Make sure to sit each day. Thirty minutes is fine, fifteen minutes is fine. The length of time will depend on your circumstances, and these vary from person to person. Be sure to set aside some time to sit every day. At that time, no matter how much you are concerned about your work or what is happening in your household, forget those things and sit in a samadhl of zazen.

From the beginning, I would like you to divide your life into Zen within stillness and Ten within activity. In this way, I believe you will be able to be one with your work and be one with a samadhi of zazen. If you do this, I believe you will not even have time to think "this is Zen." Then, during Zen in stillness, you will be able to forget yourself and be one with a samadhi of zazen.

Continue to persevere: building up your practice, it falls apart~ again building up your practice, it falls apart. In this way, I am sure there will come a time when it is no longer necessary to divide Zen in two.

CONTINUING WITH PERSEVERANCE

It is not easy to sit zazen. Zen practice is a difficult thing. Please do not lose heart and give up along the way. It is not something that must be concluded within a set number of years. Nor is it something that, if not taken care of quickly, will prevent you doing something else. I would like you to persevere steadfastly. That is what we call "continual mindfulness."

There are three things that any person who aspires to the Way of Zen must do: asking a master about the Dharma, the practice of zazen, and observing the precepts. Many people ask me how they can know if the zazen they are practicing is correct or mistaken. I will give you some guidance about this.

Mistaken zazen and mistaken guidance result when, figuratively speaking, the teacher first makes a suit of clothes and a pair of shoes into which you must make yourself fit. This is a grave error. A similar mistake occurs when the teaching prescribes that you mimic the teacher's form until the teacher releases you from the form.

In Zen it is said that all the teachings of Buddhism and Zen are "skillful means." They are like a finger pointing at the moon. If you look in the direction indicated by the fingertip you will see the moon.

The object of the teaching is to see the moon. However, the moon and the finger are one. If you are taught that the moon and the finger are separate, this is mistaken. In simple terms, as long as you do not understand, skillful means exist as skillful means. However, when you come to understand Zen, you understand that the means are also the result itself.

If you truly attain the Way, you will no longer have to think about yourself. Since it is not necessary to think of your own matters, it is possible to concentrate one hundred percent on your work, on the needs of others, and on your own families. In this way, you wiI1 feel great ease and comfort. This is the practice of a bodhisattva, the activity you are doing now becomes the practice of the bodhisattva. Please continue your endeavors diligently.

The Key to Zen

Teachings by Sekkei Harada Roshi

http://www.thebuddhadharma.com/web-archive/2003/12/1/the-key-to-zen.html

Sekkei Harada Roshi is abbot of Hosshinji, a Soto Zen monastery in Fukui Prefecture, Japan. This article is adapted from his book, The Essence of Zen, published by Kodansha International, and from several of his teachings published in Hosshinji Newsletter.

A series of short teachings by Sekkei Harada Roshi

Where Is the Way to Achieve Peace of Mind?

Dogen Zenji, the founder of the Soto Zen sect in Japan, defined Zen in the following manner: “Zazen isn't step-by-step meditation; it is simply the Dharma Gate to peace and joy. It is both the practice and the realization of totally culminated enlightenment.” Step-by-step meditation is to seek for satori , or liberation, at some time in the future. In the Soto Zen sect, the teaching is that Zen itself is satori. Because practice and realization are one, apart from practice there is no realization and within realization there is practice. If you seek to attain some result in the future, then Zen will die. That is why Dogen Zenji says, "Zazen isn't step-by step meditation."

Zen is all of human life. Walking, standing, sitting and lying down—these activities themselves are said to be satori. But there is a tendency to think that, in terms of practice, one or another activity is relatively more important. There are some people with the conspicuously heretical point of view that "Only sitting zazen is the kindest, sincerest activity of practice. Everything else is of secondary importance." But this is a great mistake. Both sitting zazen and working are the dharma. It isn't possible for there to be two dharmas within the dharma. Some people sit zazen with the objective of gathering up courage or curing an illness, but this is also-step-by-step meditation. When you sit zazen, you must only be zazen. This is what we call shikantaza . Don't make Zen impure. You mustn't add meaning or significance to it.

I am often asked, "Is there no other way besides zazen to achieve peace of mind?" I answer, "No." Zen is to assimilate the whole dharma (truth); it is to be one with it. If within the religions of the world the various practices taught direct one to assimilate the dharma irrespective of the distinction between liberation through one's own effort (jiriki) and liberation through the power of some other being such as Amida or God (tariki), then it must be said such teachings are Zen. If we get hung up on the word "zazen," there is a tendency to think it is some special practice, but it isn't. Consequently, Zen is the only way to attain peace of mind.

The Functions of the Body, Speech and Thought

One big mistake made by many people concerning zazen is thinking that it is limited to the form in which we sit in meditation. Actually, all functions of the body, speech and thought must be zazen. Zazen of the body refers to the posture of sitting straight, crossing the legs and holding the hands together. Zazen of speech includes the words we use during the day, seasonal or morning greetings, the Heart Sutra which we chant during the morning sutra service and the verses chanted before eating, as well as the various words used throughout the day. Lastly, zazen of thought is the functioning of the mind, something that we cannot see. Thinking various ideas, planning, devising, discriminating and so on—all movements of the mind are zazen.

On saying, then, that all functions of the body, speech and thought are zazen, it is easy to fall into the trap of thinking, “Why is it necessary to do zazen or seek something by means of Zen?” The problem here with thinking “all activities are zazen” is that we know it by means of learning. It is merely intellectual understanding. Reality is therefore divided in two—subject and object—and the thought arises that there is no need to do zazen. We must be careful about this.

The Problem of the Self that Knows

In the beginning, Zen Master Dogen had a question, which can be expressed in the following way: “The teaching of Buddhism is that this body itself is Buddha. Essentially, a human being is Buddha, the dharma and Zen. Why, then, is it necessary to practice?” As there were no teachers in Japan who could resolve this question for him, he went to seek the answer in China. After a long period and many hardships, he finally met Zen Master Nyojo, and then “cast off body and mind.” At that time he said:

“Willows are green, flowers are red.” Or, “All human beings are endowed with buddhanature.” Or, “All beings are essentially Buddha itself, are Zen itself.” Dogen said unequivocally that there is no mistake in these statements either before or after “body and mind are cast off.”

From the vantage point of the dharma, everything is empty. There is no need to “cast off body and mind.” We are already within that state of freedom. Why, then, can't you accept all phenomena as they are? The only major problem lies in whether, in the activities of seeing, hearing, experiencing and knowing, the ego-self intervenes or whether it has completely disappeared. It is because of the intervention of the ego-self that you cannot accept things as they are. This is something I would really like you to be aware of. It is in order to completely wash away the intervention of the ego-self that zazen is so necessary.

Many people mistakenly think: “What I'm now observing and experiencing is my real self. To forget that self or to accept another true self is unnecessary.” This is how most people think. Others, on perceiving the self as an object, think: “I must let the self drop away. The ego-self must be let go of.” If you think this way, please understand that it is a serious mistake.

All beings and all phenomena of the world (mountains, rivers, grass, trees and so on) are composed of the four elements—earth, water, fire and air. These elements have no fixed center; they freely change according to circumstances. However, if “I” is fixed as a sort of center or source, then it is no longer possible to change freely anymore. Fixing the “I” in this way is the source of delusion. And because “I” is perceived as existing, the deluding thought arises that there must be something that is the source.

In the beginning, Shakyamuni Buddha also thought that there must be something that is the source, or origin, of suffering. This was the reason he began to practice. But on seeing the morning star, that is, on realizing enlightenment, he knew that there was no source of suffering. In other words, all things arise because of conditions and all things disappear for the same reason. He realized that all phenomena are produced by causation (Jap., engi ; Skt., pratitya-samutpada ). In order to explain causation, Shakyamuni built a “ghost castle” and named it emptiness.

Emptiness is an explanation of oneness, where there is not the slightest gap for the opinions of the ego-self to enter. Please consider emptiness as a condition where all conceptions have been taken away. The quickest way to be free of such deluding opinions is Zen. It is unnecessary to repeat this, but I would like you to remember that zazen is all the activities of the body, speech and thought. I often use words like “Zen,” or “the dharma,” or “the Way.” Please remember that these are all references to the same thing.

Three Essential Elements of Zazen Practice

There are three elements you cannot do without in Zen practice: asking a master about the dharma, the practice of zazen, and observing the precepts. The objective of Zen practice is to graduate as quickly as possible from zazen and return to the time before you knew anything about zazen.

Some people become intoxicated with zazen and in this way lose sight of their real self. They mistakenly fall into the habit of thinking that they are doing zazen wholeheartedly. Such people are a long way from true Zen practice.

Others mistakenly teach that zazen is very good for your whole life and simply ask people to sit. However, if zazen is not free of all viewpoints, such as good and bad, it isn't the real thing. It is all right, though, to take time off from your busy life and work in order to develop your powers of concentration by absorbing yourself wholeheartedly in Zen practice.

With regard to the first element—asking a master about the dharma—Zen Master Dogen had advice for people who don't know what to do if they cannot find a true master. He cautioned them strictly, saying, “In such a case it is best to stop practicing temporarily. There is less danger in quitting than in practicing in a mistaken manner.” The reason is that practicing is like crossing the ocean without a chart—there is always the danger of unknown reefs.

Concerning the second element, the practice of zazen, it is less dangerous for those who have no master to devote themselves to their work instead of doing zazen in a mistaken way. Simply lose yourself in your work and become engrossed in it.

The last essential element is observing the precepts. This involves leaving all things as they are, without interfering or imposing your own opinions on the way things are. If you are free from your ideas, then the precepts are already observed even before you intend to do so. Why is it necessary to do things the way they have been decided? All things have laws or principles that govern them. To observe the precepts is to follow those laws. Observing the precepts means that all things are one and there is no way to interfere with that oneness. A person who can live life following these laws or rules—whose life is in accordance with these laws—is a Buddha. This is a life in which cause and result are one.

If you sit for a long time, your legs will gradually begin to hurt. No matter how long a person has been sitting or how much experience he or she has, there will always be times when your legs hurt. The only difference is whether or not you lose your zazen method because of the pain. It isn't good if the pain in your legs stops you from practicing. In that case, you and zazen are two separate things. You must be able to leave the pain in your legs as it is and still be able to do zazen properly.

When the power of zazen is weak, you end up going off in the direction of whatever condition arises. But when the power of zazen is strong, no matter what arises, zazen is right there. It is easy to realize the Way if you sit like that.

The practice of Zen is the study of the self. It isn't a matter of following the words of some Zen master, whether written or spoken. I would like you not to be mistaken on this point. Don't look for Zen in the Buddhist teachings or in the words of a teacher. The role of a teacher is to keep a person going in a straight line in the study of the self.

“Once in a Lifetime, This One Encounter”

In the tea ceremony, the expression “once in a lifetime, this one encounter” is often used. The usual way this is interpreted is “a one-and-only encounter.” In Zen, though, we interpret this expression in the following way: In the course of our lifetime, there is one person we must meet. No matter through which grasslands we may walk or which mountains we may climb, we must meet this person. This person is in this world. Who is this person? It is the true self. You must meet the true self. As long as you don't, it will not be possible to be truly satisfied in the depths of your heart. You will never lose the sense that something is lacking. Nor will you be able to clarify the way things are.

This is the objective of life as well as of the teaching of Buddhism—to meet yourself. The shortest, most practical way to do this is through Zen.

Throwing Away Your Standards

The key to Zen is that no matter how important something is, it must be thrown away. Keep on throwing and throwing and throwing away your standards.

Noh is one of the traditional drama forms of Japan. The following story about a Noh actor named Konparu Zenchiku (1405-1470?) illustrates how one man threw away all the opinions he had been using as standards. Konparu Zenchiku made a great effort to practice zazen and later received certification of his realization from his master. He expressed the condition of having forgotten the ego-self (the condition in which all standards have been thrown away) in this way: “No matter how I look at it, there is nothing blacker than snow.” His master said, “If you understand that, then all is well,” and he gave him the certification.

All of you here are deeply cultured and have considerable knowledge. I would like you to forget all of your standards just once. Then you will be able to use them in a more meaningful way. My only wish is for you to throw away the standards you have had until now, and later you will be able to use them in a more vital way. If you are free from any viewpoint, then you live for the sake of the dharma.

Also Forgetting Satori

I would like to speak about kensho (to realize that the self has no self-nature) or satori , the thing that people who practice zazen are most curious about. Kensho, satori and Great Enlightenment are different words, but they must represent the same thing. It seems that in some books it is written that there are different depths or levels of enlightenment, but in Zen there are no such distinctions. Kensho or satori must be something which only happens once. If levels or depths are spoken of, then it must be said that this is proof the final result has not been attained. From long ago, it has been said that Zen practice is very strict, but in fact the only strictness of Zen relates to whether or not kensho is truly acknowledged.

Kensho or satori is the condition of being free of all delusion and perplexity. Of course, delusion arises because of the attachment to the ego-self and so it only makes sense that the ego-self must be cast off. Essentially, there is neither ego-self nor delusion. Consequently, it isn't possible to say that the result of Zen practice is to have become selfless or that delusion has disappeared. Essentially, these things do not exist, but some time ago you came to think of them as existing (that things exist outside of you), which is a delusion arising from attachment to the ego-self. Kensho is to return to the original condition where things have no substance.

This doesn't mean that because of kensho or satori you become a special person. It is a great mistake to think that kensho or satori is the final objective of practice. The dharma which the Buddha expounded came after his Great Enlightenment. Consequently, to think in terms of a specific goal is only to do so within the teaching called the Way of Buddha. Forget Zen, forget satori, forget practice. Finally, you mustn't forget that practice is to forget what has been forgotten.

To Really Know that the Five Skandhas Are Empty

All dharmas (things) are the myriad distinctions both with and without form that arise from the five skandhas. These are all things which appear because of causes and conditions and so they have no substance. The five skandhas are: matter, sensations, thoughts, perceptions and consciousness. A skandha has the meaning of things piling up and collecting. Sometimes these things appear individually; at other times combinations of them coalesce. However, it is necessary to realize that the things that coalesce are empty. In the widest sense, the five skandhas are heaven and earth. In the narrower sense, they are the human body. That is why we say that human beings are microcosms of heaven and earth. And heaven and earth are a macrocosm of a human being.

As I have said before, matter is comprised of the four basic elements: earth water, fire and air. Earth is bones and flesh, water is blood, fire is body temperature and air is the breath. Through the harmonious interactions of causes and conditions, these elements form human beings and all other things. In the case of people, matter is the human body. Sensations are the sense functions, which in response to a myriad of conditions receive impulses such as suffering, enjoyment and rejection. This is the source of delusion. The skandha of thought refers to the unlimited flow of never ceasing thoughts. Depending on the manner in which we think, these thoughts can be delusive. Perception is the condition whereby perceiving things other than us, the mind continues to maintain that image. Consciousness is the totality of the mind and is comprised of the function of discrimination. It is because of mistaken judgment that we create a distinction between enlightened and unenlightened. Consciousness is also called mind or mind only. In any case, if something is perceived, that is delusion; if there is no perception, that is satori.

Matter is the actual human body. Sensations, thoughts, perceptions and consciousness are mental functions which cannot be seen. The objective of Buddhist practice is to truly know that the five skandhas are completely empty as they are. Completely empty means that all things coalesce through causation and so it isn't possible to perceive substance. Both matter (things with form) and sensations, thoughts, perceptions and consciousness (things with no form) are ever-present. They cannot be separated and that is the meaning of the expression, "Body and mind are one."

Fundamentally, you must realize that views and opinions created by the ego-self arise because of the delusive attachment to the ego-self consciousness. It isn't enough just to sit zazen. It is important that you clearly understand the rationale of the dharma which I have mentioned above. In order to realize liberation, it is both important and necessary to know such things. The most important issue for human beings is, by means of religion, to become free of the restraints of God and Buddha, to be liberated from dualistic thought and discriminations, such as believing and not believing, and to awaken to the essential self.

Question: Should a person who has lost the ego-self be called a Buddha?

Harada Roshi: Buddha is only a provisional name. It isn't really possible to attach a name to something which has no center, is it? However, the Patriarchs, those people who attained “no-self,” used various names to refer to this condition. To give one example, long ago in China there was a priest named Zuigan. Everyday he would call out to himself, “True Self! Are your eyes wide open?” “Yes, yes.” Then he would say, “Don't be fooled by others (symbols).” “No, no,” he would answer. He lived his life always admonishing himself in this manner.

I think you all have mirrors at home. If you have time, why not try facing a mirror and calling out “True Self” (Roshi laughs).

I understand the story. But in real terms, how should I live my life?

No matter how much we think about the past, it isn't possible to change it. And in the same way, even if we worry about how we should live our life in the future, finally this is something we cannot know. So, it is important that we be able to live now without feeling dissatisfied or discontented.

It is because we think there is a center to something that essentially doesn't exist that all delusion and suffering arises. So to truly accept that there is nothing which is the center, or in other words to ascertain that there is no ego-self, the only thing we can do is to become a Buddha. This is what I mean by living life with no discontent. At the very least, it is important to be one with now and then forget that thought of being one. It is important to live with this attitude.

The Awakened Self,

Harada Sekkei Roshi

Buddhism Now, August 2000

http://buddhismnow.com/2013/05/21/the-awakened-self-harada-sekkei-roshi

The following is from a 1993 television programme, ‘The Awakened Self'—an interview with Harada Sekkei, abbot of Hosshinji Training Monastery by Shiratori Motoo, a former NHK-TV presenter.

Mr Shiratori: Excuse me for disturbing you during the middle of sesshin.

Harada Roshi: Thank you for coming.

S: Sesshin is a time when people concentrate on zazen. This is an important thing in Zen, isn't it?

Roshi: Yes. Going back for quite a long time, sesshin is an important activity which has been strictly practised in Zen temples. Although it may sound a bit strange to say, sesshin is very effective or fruitful for a person's zazen. It's definitely a way of expanding a person's state of mind.

S: You follow quite a strict schedule during sesshin, don't you?

Roshi: We get up at 4:00 am and until 9:00 pm spend most of our time in the zendo. We, of course, sleep in the zendo, as well as eat there, too.

S: You really pack it in, don't you?

Roshi: Yes. But not only within the zendo, in the individual rooms or while drinking tea after meals as well. These activities must all be Zen. Zen is walking, sitting, standing, and lying down; in other words, all of our everyday activities. My request is that especially during sesshin everyone concentrates on each activity.

S: I took a look inside the zendo and saw many foreigners there.

Roshi: There are about thirty foreigners here for this sesshin. Usually we have about that many come for each sesshin.

S: From which countries?

Roshi: This time there are people from America, Germany . . . Also there are two men from India living here.

S: The two in the yellow robes?

Roshi: Yes. There's a person from Switzerland as well as others from other European countries. Some stay for a long time, others do not. But there are many.

S: People from the general Japanese public are here, too. How does that work?

Roshi: Hosshinji is an official training monastery. However, for the last eighty years or so lay people have been permitted to attend sesshin. They are requested to follow the same rules as the monks and if they can, they are allowed to come and sit sesshin.

S: Eighty years ago would be the Taisho Period.

Roshi: Yes. At most training monasteries, I think there is quite a bit of resistance to having lay people come and sit zazen. Out of consideration for those with ‘bodaishin'—the mind which seeks the way of liberation—lay people are allowed to come and sit with us.

S: In conveying Zen to people of other countries, there must be differences which appear.

Roshi: Some changes must be made. For example, one person said, ‘We've already learned enough from religions in the form of teaching, including Buddhism, but I want to know what is the essence of those teachings?' I explain that the essence is the Dharma [truth]. Buddhism, or the Buddhadharma, is the religious teaching based on the Dharma as expounded by Shakyamuni [the Buddha]. This teaching came into being because he clarified himself. So if you people here truly clarify yourselves, then the teaching becomes your own. This means that the Dharma doesn't belong to any one single person. It belongs to anyone who grasps it. It doesn't only belong to Shakyamuni. Since it belongs to those who grasp it, if those people expound what they have grasped, then it becomes their teaching. This means it isn't only restricted to Shakyamuni's teaching.

S: This means that the teaching and the Dharma are different.

Roshi: Yes. When Bodhidharma went from India to China, he met the emperor of China, Wutei. The emperor had a great intellectual understanding of Buddhism and asked many questions, but Bodhidharma rejected all of it. He realised that in such conditions there would only be the possibility of spreading the teaching, but no chance to spread the Dharma. So Bodhidharma went into the mountains and sat for nine years in a cave facing the wall. In that way he demonstrated the Dharma itself. In other words, Zen, sitting, single-minded sitting—this is the Dharma. He sat without giving explanations. Finally, as he had thought, he was able to foster a great disciple, Taiso Eka.

S: Is that why you gave the Dharma talk in America in which you said the people there shouldn't understand Zen or the Way of Buddha conceptually or intellectually?

Roshi: That's right. The Chinese characters for the word ‘religion' mean ‘the teaching of the source'. Therefore people generally think that all religions, including Buddhism, are teachings of the source. I think there is the danger of getting them confused. There is a need to point out that the teaching of Buddha is slightly different from other religions.

As long as we do not clarify ourselves, we hear the teaching through the self, the ego, and then interpret the teaching in numerous different ways. This means there is a big gap. So no matter how well or clearly you have studied and learned the teaching, you still won't reach the Dharma. The teaching of Buddhism is “no self” because it is the teaching of someone who has truly got rid of the ego. As long as the ego exists, it isn't possible to truly hear the teaching.

S: It seems like a whole life of self-contradiction.

Roshi: This means that the people sitting sesshin here are hearing the teaching even though they don't really understand it. ‘Be selfless!' But they are still practising within the confines of the ego. Until a person truly forgets the self, it won't be possible to truly practice and become the teaching of Shakyamuni.

S: That means inevitably the ego is included within understanding the teaching and the world of the Dharma is apart from that understanding.

Roshi: That' s right.

S: Is this the meaning of the Zen expression ‘no dependence on words and letters'?

Roshi: Yes. Zen was brought to China from India by Bodhidharma. But before he arrived in China, the teaching of Buddha (i.e. the sutras), had been there a long time. This teaching was like a prescription for medicine.

S: A prescription?

Roshi: If your head hurts, then take this . If you have a stomach ache, then take this . At that time there was only this kind of discussion. Then Bodhidharma arrived. He embodied the Dharma itself. He pointed out that debating and arguing about this and that has nothing to do with the real teaching of the Buddha. However, they were only accustomed to the intellectual teaching of Emperor Wutei and other scholars. The teaching of Bodhidharma seemed to be strange and unusual for them, so none of them could believe it. Bodhidharma knew that the Dharma would die even if the intellectual teaching of Buddhism was passed on. Coming to this conclusion, he went to the mountains.

S: It's not in the letters. It's not in sutra books.

Roshi: That's right. It must be ‘a special transmission outside the teachings'. There is something which must be transmitted separate from the teachings. That is the meaning of ‘no dependence on words and letters; a special transmission outside the teachings'.

S: Then by means of zazen it is possible to reach the world of the Dharma without relying on the sutras.

Roshi: Yes. It is important to know that it isn't possible to use zazen or Zen as a means to reach the final point which is the world of the Dharma. Zen itself is the Dharma itself. This is something you can realise for yourself, ‘Ah, so that's the way it is!' To simply sit and think about concepts which appear in the sutras like KU (emptiness) or MU (nothingness) and imagine what they're like isn't Zen. If that is what people are going to do, they may as well go to school and study various commentaries on the sutras.

S: I've read your book, which is a compilation of your Dharma talks. In it, expressions such as ‘true person of the Dharma' or ‘a liberated person' or ‘true peace of mind' appear. Now hearing you say that the teaching and the Dharma are different, I wonder what is a ‘true person of the Dharma'.

Roshi: A ‘true person of the Dharma' includes everyone, regardless of whether they've made the Dharma their own or not, or whether they've experienced satori or not. This is to say that we are only able to perceive the past and the future. What is the present which divides past and future? ‘Now' or the present is impossible to perceive. There is no so-called ‘now', no instant which you can say is ‘now'. This is exactly what we explain with the word ‘Dharma'. This means that something which cannot actually be perceived is explained simply as the Dharma, so at least we can perceive it intellectually. To grasp the Dharma, then, means for the self to assimilate something which doesn't exist. We can only perceive the past and future and yet certainly there is the present, even if it isn't possible to know it. It's not there and yet it is, the moment ‘now'.

S: We usually think we understand the moment ‘now'.

Roshi: But that is in the past. To understand something creates a distance. Because there is a distance, we can see something. If we can't see something, it is because there is no distance between it. This means we are one with it. The condition of being one with things is explained as the Dharma.

S: That means that we are within the Dharma?

Roshi: Yes. To sit and realise, ‘Yes, that's the way it is.' This is what we call satori . This means there is no one who is not liberated. It is simply a question of whether you realise it or not. This means that there is no one who cannot awaken by practising according to the correct teaching. Satori is your own reality. Anyone can realise it.

S: The Dharma itself. What interferes? What are the obstacles?

Roshi: In Buddhist terms, we say it is ignorance. Essentially all is one. Ignorance is to divide that in two—subjective, objective. No one can think these two thoughts at the same time—subjective and objective. Or good and bad. Or like and dislike. No one can consciously think two things at the same time. But because we are changing so rapidly, we think we can think subjectively and objectively or good and bad at the same time. For that reason we compare. But in fact it isn't possible to compare. As long as one thought doesn't disappear, another new one cannot appear. And yet it seems as if we can compare good and bad. This is the human condition.

S: This sort of thinking, then, is delusion.

Roshi: That' s right. It is the function of the ego. No one is born a buddha. We say everyone is a buddha, so this may seem contradictory. But without going through the process of ignorance and clarifying it, it isn't possible to understand that you are Buddha and an enlightened being.

S: So we are endowed with Buddha-nature at birth. But as human beings we are also born into a condition of ignorance.

Roshi: That's right. For example, these days salt is manufactured from sodium nitrium, but formerly salt was refined from sea water on salt beds. Yet it isn't possible to use sea water to flavour food simply because it is salty. It must be refined into salt using appropriate procedures and then it can be used to season food. Without this process, it doesn't become salt nor will we become buddhas.

S: This means that we all essentially possess the nature of salt, but we are still like ocean water.

Roshi: Yes. Of course sea water can be used to some extent, but there are limitations. It must be made into salt. In Buddhism we refer to this process as practice. And when it finally becomes salt, the practice has been accomplished. This, in other words, is liberation or satori .

S: So putting the sea water on the salt beds, that process is zazen.