ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

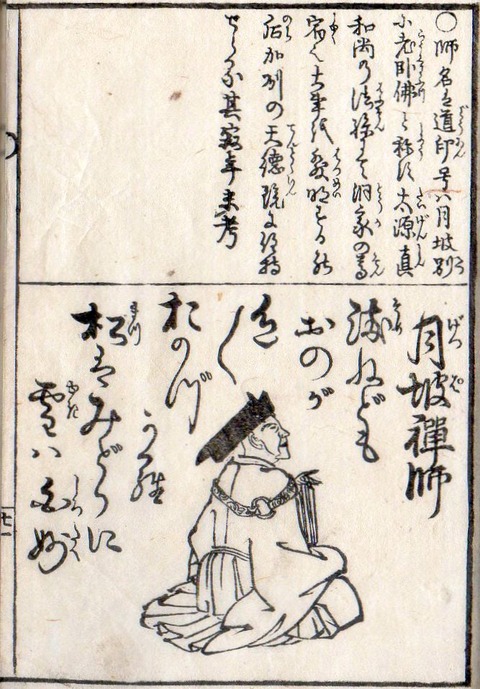

月坡道印 Geppa Dōin (1637-1716)

aka 月坡道印 Gappa Dōin (がっぱ どういん)

Pen name: 老臥仏 Rōgabutsu

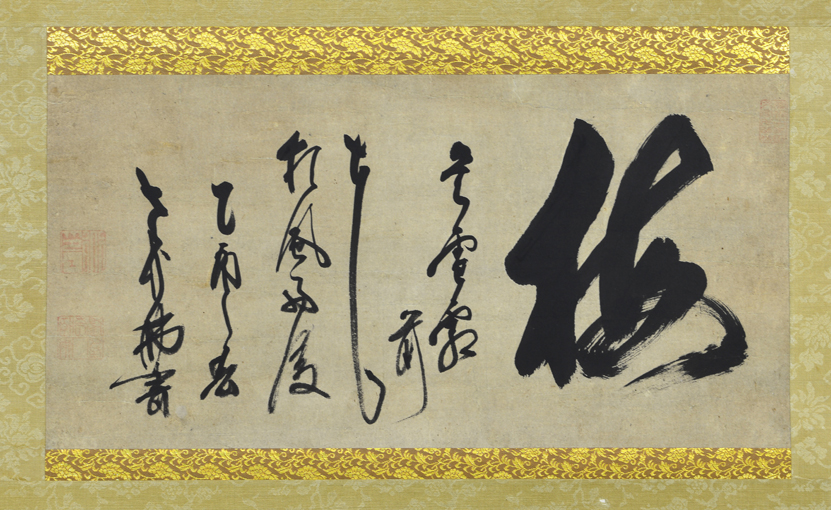

語 句 : 梅 是雪霜の前 花風を打って渡るに好し 乙酉( 1705 )春 老臥佛書

寺 院 : 曹洞宗 加賀献珠寺 常陸天徳寺 加賀天徳院3世 京都大宝寺開山

別号・他 : 号は老臥仏。和泉蔭涼寺鉄心道印に参じ、加賀天徳院二世龍睡愚穏の法を嗣ぐ。 前記鉄心は天徳院一世。寛文 9 年(1669)永平寺で首座となり、後加賀献珠寺、常陸天徳寺、加賀天徳院三世と歴住する。 山城大宝寺の開山にもなっている。 月坡は詩僧として知られ、語録に 「月坡禅師語録」 がある。

本紙寸法 /cm: 27.2*54.5 全体寸法 /cm: 112*65.8

Text: Plum flowers. The flower of the plum blooms before snow frost, a wind is blowing with fragrance. In the spring , 1705. Painted by Rogabutsu.

Temple: The Soto sect. The third abbot of Tentoku-in in Kaga. The founder of Daiho-ji, Kyoto.

Data: Pen name: 老臥仏 Rōgabutsu. Dharma heir of Ryusui Guon who was the second abbot of Tentoku-in. He also practiced Zen under Tesshin Doin who was the founder of Tentoku-in. He became the abbot of Kenshu-ji in Kaga, Tentoku-ji in Hitachi and the third abbot of Tentoku-in in Kaga. He was the founder of Daiho-ji in Kyoto. He elevated Chinese-style poetry and was praised as the best priest poet in Soto Zen sect. His poems were recorded in "Analects of Geppa Zenji" [Geppa zenji goroku, 1677].

Paper Dimension /cm: 27.2*54.5 Whole Dimension /cm: 112*65.8

Taishō Shinshū Daizōkyō (大正新脩大藏經)

月坡禪師語録 (No. 2595_ 月坡道印 語 月坡道印 編 ) in Vol. 82

[Geppa zenji goroku, 1677]

http://21dzk.l.u-tokyo.ac.jp/SAT/ddb-sat2.php?mode=detail&useid=2595_,82,0521&nonum=&kaeri=

http://21dzk.l.u-tokyo.ac.jp/SAT/ddb-sat2.php?mode=detail&useid=2595_,82,0521&nonum=1&kaeri%20=

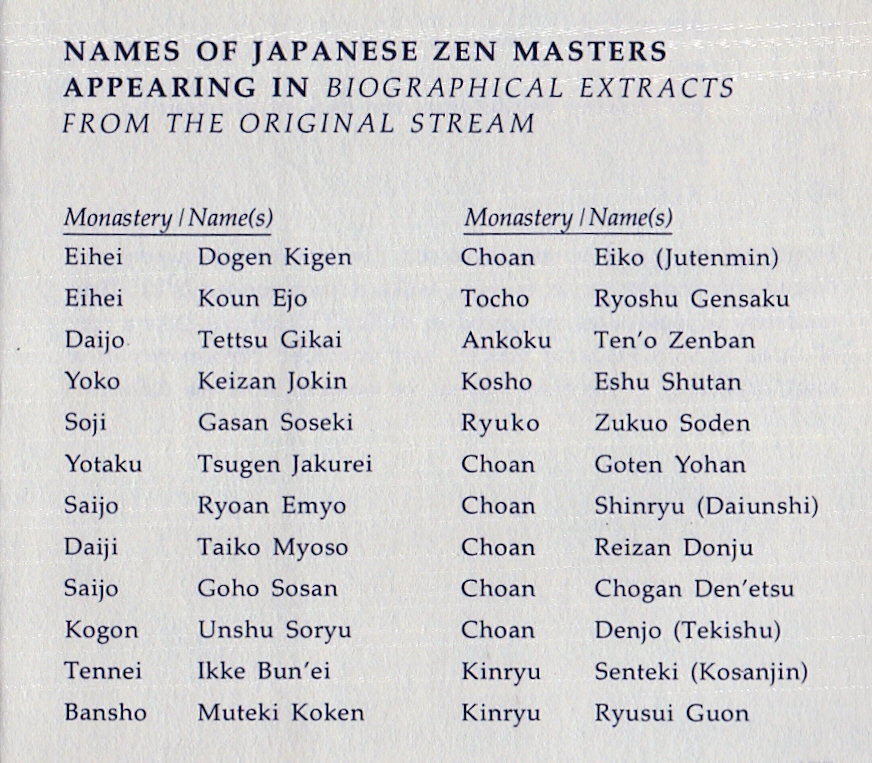

BIOGRAPHIES OF

JAPANESE

ZEN MASTERS

from Biographical Extracts of the Original Stream

compiled by zen master 月坡道印 Geppa Dōin (1637-1716)

Translated by Thomas Cleary

In: Timeless Spring, A Soto Zen Anthology,

Weatherhill / Wheelwright Press, Tokyo - New York, 1980,

pp. 27-28, 95-99, 106-112, 138-167.

According to Geppa Doin (1644- ?), one of the eminent

Soto teachers of the Tokugawa period revival of zen in Ja-

pan, the school of Dogen, from its beginnings in the 1230's

and 40's, flourished from the late 1200's to the early 1400's,

faded in the mid-fifteenth century, declined after the late

fifteenth century, and had been continuing weakly for two

hundred years. Geppa's Biographical Extracts of the Original

Stream chronicles the highlights of the succession of his

lineage through twenty-four generations from Dogen to the

seventeenth century zen master Guon, Geppa's final

teacher. As zen is not a doctrinal school but a succession of

living exemplars, the chain of transmission has a profound

meaning in zen which has nothing to do with school or

sect. This book is both conventional and illustrative his-

tory, tracing evidence of the communication of the inmost

mind of zen through the vicissitudes of centuries.

Life of Zen Master Dogen of Eihei

[永平] 道元希玄 [Eihei] Dōgen Kigen (1200–1253)The zen master's name was Dogen. He was from Kyoto.

His lay surname was Minamoto, and he was a descendant

of emperor Murakami (r. 946-967). He left society as a

youth and was ordained by Koen of Yokogawa. Before

many years had passed, he had read the whole buddhist

canon two times.One day he resolved upon that which is outside the

teachings (zen); he left and called on Eisai of Kennin

monastery and Gyoyu at Jomyo monastery. Eventually he

attained the Dharma in the tenth generation of the

Huanglong succession."When he heard someone extolling the zen way in Sung

China, he went right to China on a merchant ship. He

went to ask about the quick way to enter the path from

Liaopa Wuji at Tiantong mountain, Cheying Ruyan at Jin

Shan, Yuankao at Wannian monastery, Sitiao at Xiaosuian:

he didn't agree with any of them - he thought to himself

that there was no teacher in China better than he himself.When he first lay down his staff at Tiantong, the com-

munity decided to place him as a novice2 because he was

from another country. The master was not happy about

this, and appealed in writing to the emperor; after three

times he finally got his wish. From this his name was

heard far and wide.The next year he met Rujing, who had come to dwell at

Tiantong. The master greeted him joyfully, and as soon as

Rujing saw him, he esteemed him as a vessel of Dharma.

The master submitted to him in all sincerity and entered

his room." He meditated diligently day and night, never

lying down.One night as Rujing was passing through the hall, he

saw a monk sitting dozing and said, "For this affair it is

necessary to shed body and mind - if you just sleep like

this, when will you ever have today's affair?" Then he

took off his slipper and hit the monk. The master, nearby,

got the message and was greatly enlightened. The next day

he went to the abbot's quarters; Rujing laughed and said,

"The shedding is shed ." At that time Kuangping of

Fuzhou was standing by as Rujing's attendant; he said, "It

is not a small thing, that a foreigner has attained such a

great matter." The master bowed. After this he worked

most earnestly and attained all the secrets.When he was taking his leave to return east, Rujing im-

parted to him the essential teachings of the Dong succes-

sion4 and the patched robe of master Furong, saying, "You

should go back east forthwith; just spread the teaching so

it will never end." The master accepted with bowed head

and finally returned. When he began to teach in Fukakusa,

south of Kyoto, everywhere they honored him as the first

patriarch of Soto zen in Japan.The master said, "I did not visit many monasteries, but I

happened to meet my late teacher at Tiantong and directly

realized that my eyes are horizontal and my nose is verti-

cal; I was not to be fooled by anyone. Then I returned

home with empty hands. Thus I have no Buddhism at all; I

just pass the time as it goes: every morning the sun rises

in the east, every night the moon sets in the west. When

the clouds recede the mountain rises appear; when the

rain has passed, the surrounding hills are low. Ultimately,

how is it? Every four years is leap year, the cock crows at

dawn."Later in life he built Eihei, Sanctuary of Eternal Peace, in

Echizen province, and lived there . Before long people came

in droves . His monastery regulations were just like those

of Tiantong: it was the first strictly zen monastery in Ja-

pan. At that time (1243-47) the emperor (Go-Fukakusa)

sent down an edict granting him a purple vestment of

honor and the title Zen Master of Buddhism. A chamber-

lain brought the order; after giving thanks for the favor, he

strongly refused it several times, but the emperor would

not allow this. So Dogen eventually took it and offered a

poem which said,Though the mountain of Eihei is insignificant

The imperial order is repeated in earnest:

After all I am laughed at by monkeys and cranes,

An old man in a purple robe.The emperor long admired him.

The master was fond of seclusion and built a separate hut

under Crystal Cliff as a retirement retreat. He wrote poems

such asThe ancestral way which came from the west, I have brought east-

Fishing in the moonlight, pillowing in the clouds, I have tried to emulate the ancient way.

The flying red dust of the conventional world cannot reach

This reed hut on a snowy night deep in the mountains.and

The wind is cold in my three room reed house:

Observing my nose" I first come upon the fragrance of autumn chrysanthemums.

Even with an iron or a bronze eye, who could discern?

In Eihei nine times I have seen the fall.The assistant commander of the Taira, Tokiyori, es-

teemed the master's way and several times called him to

stay at famous temples, but he didn't go . After a long time

the master went on his own to call on him . The assistant

commander greeted him and saw him off; he paid obei-

sance to Dogen as a disciple, and asked him about the

path and received the precepts from him. The master

passed the year and then returned.In the end he summoned his disciple Ejo and imparted

his final instructions. He then wrote a verse and died. The

verse said,He was fifty four, and had been a monk for thirty-sevenFifty four years illuminating the highest heaven,

I leap into the universe.

Ah, there is no place to look for my whole body:

I fall living into hades.

years. His monument was built at Eihei, and he was enti-

tled Joyo, Heir to the Sun.

NOTES TO BIOGRAPHY OF DOGEN

1. Huanglong was one of the branches of the Linji (Rinzai)

2. In a monks' hall or meditation hall, the seating arrangement

school of zen in China, to which Eisai had succeeded. Dogen also

studied with Myozen at Kennin monastery; Myozen was consid-

ered Eisai's foremost disciple.

determined by seniority or ordination age.3. Entering a zen master's room for personal encounter and in-

struction is a special part of zen practice; Rujing is said to have

allowed Dogen to enter his room without formality, to discuss

anything he wanted; the Hokyoki mentioned previously was a

reord of Dogen's conversations with Rujing in his room.4. This probably refers to the teaching of the five ranks of Dong

Shan, the Baojing sanmei and Can Tong Qui: secret oral instruction

on the application and interpretation of these formulae seems to

have been part of the 'transmission of Dharma' from a teacher to

an awakened disciple.5. Fixing the attention on the nose is one method of breath con-

templation; it is also called 'stopping.'

Ejo of Eihei

孤雲懐奘 Koun Ejō (1198-1280)The master's initiatory name was Ejo; he was styled Koun

(Solitary Cloud). He was from Kyoto; his lay surname was

Fujiwara and he was a descendant of the prime minister

Tamekichi of the Kujo branch of that clan.Ever since childhood he did not like to live in society;

he first took Enno of Yokogawa as his teacher, shaved his

head, put on monks' clothes, and was fully ordained. He

studied the essentials of the scholastic schools, and gained

a reputation. One day he lamented, "The four schools of

Kusha (Abhidharrnakosa), Jojitsu (Satyasiddhi), Sanron

(Madhyarnika). and Hosso (Vijnanavada and

Dharmalaksana) are all studies of the compounded; the

two doors of cessation and insight (Tendai) and pure land

(buddha name remembrance) still do not exhaust the

profound mystery."Then he knew these were not the boat for leaving the

world; so he gave them up and called on Kakuen at

Tomine and asked about the teaching of seeing reality to

realize buddhahood.1 Kakuen esteemed him deeply as a

vessel of Dharma.Next he called on zen master Dogen at Kennin

monastery. Dogen cited the saying "one hair pierces

myriad holes" to question him closely. The master silently

believed in Dogen and submitted to him. After that he had

no desire to go anywhere else, so he changed his robe and

stayed there.Before long Dogen moved to Fukakusa and the master

went along with him. He observed and investigated day in

and day out, never careless in his actions. One day in the

hill, just as he was setting out his bowl, he suddenly

attained enlightenment . He immediately went with full

ceremony into Dogen's room.2 Dogen asked him, "What

have you understood? " Ejo said, "I do not ask about the

one hair ; what are the myriad holes?" Dogen laughed and

laid, "Pierced." Ejo bowed. Afterwards he asked to serve

as Dogen's personal attendant, taking care of his robes and

bowl. For twenty years he never left his seat beside

Dogen, except for a dozen or so days when he was sick.One day Dogen said to the master, "I first had you take

care of monastery work because I wanted to make the

teaching last. Although you are older than me, you will be

able to spread my school for many years . Work on this."

At this point the master Ejo began to expound the teaching

too; as Dogen heard him speak, he explained the subtleties

for him.When Dogen died, the master Ejo succeeded him and

led the congregation, with no sign of laziness or weariness

day or night, in cold or heat. He took the bearing of the

teaching of the school as his own responsibility, and the

whole congregation, which never numbered less than fifty,

gladly obeyed him. Great ministers and important officials

came to him and paid obeisance. Henceforth the To

succession 3 would flourish greatly.Late in life he entrusted the teaching to Tettsu . Having

personally transmitted his bequest and final teachings, he

wrote a verse and died sitting.The master Ejo was always strong and sturdy by nature,

capable of austere practice. He used to lead followers out

to Nakahama in the district to practice austerities and carry

on the teaching.

NOTES

1. This refers to the Bodhidharma sect, started in Japan by

Kakuen's teacher Dainichi Nonin, a Tendai monk who

specialized in meditation according to the zen tradition

transmitted by Saicho in the early ninth century.2. Full ceremony means at least three bows before and after and

proper manner of speech and physical deportment.3. Geppa's collection of biographies refers to what we call Soto

zen to the To succession, referring to Tozan (Dong Shan), the

ancestor; Dogen's lineage was through Yunju (Ungo), not Cao

Shan (Sozan), and Japanese tradition has it that the Cao (So) of

Cao Dong (SoTo) comes from Caoqi (Sokei), a place name

referring to the illustrious sixth patriarch of Chan, Huineng

(Eno).

Gikai of Daijo

徹通義介 Tettsū Gikai (1219-1309)The zen master's initiatory name was Gikai; he was styled

Tettsu. He was from Etchu, and his lay surname was

Fujiwara. He was a distant descendant of the general

Toshihito. When he was young he served Ekan at Hachaku

temple as his teacher, and studied the three scriptures of

the pure land teaching, the Surangama Scripture,' the

teaching (of zen) of seeing reality, and others. After he was

fully ordained he left and travelled around; first he called

on Zen master Dogen at Fukakusa. He was strong and

pure by nature - he worked at chores and practiced medi-

tation every day, excelling all others. When he heard

Dogen say in a lecture, "This truth abides in the state of

objective reality; the features of the world are permanent"

- in the spring scenery the hundred flowers are red;

doves are crying in the willows," he suddenly had an in-

sight.Before long he moved to Eihei with Dogen; the master

asked to be water steward, and personally carried water

from Hakkyoku peak. He worked for the community for

years. Because he was capable of hard work, Dogen ap-

pointed him chief cook and monastery supervisor at the

same time. So day and night he took care of a hundred

matters, without tiring; in between he worked on medita-

tion even more than others in the community. Dogen

called him a true worker on the way.Later, when Ejo inherited the seat at Eihei, the master

Gikai assisted him. One day when he went to the abbot's

room, Ejo asked, "How do you understand the shedding

of body and mind?" Gikai said, "'I knew barbarians had

red beards; here is another red bearded barbarian."'3 Ejo

agreed with him. Subsequently Ejo used differentiating

stories" of past and present to refine him thoroughly. After

a long time at this he obtained the teaching."He aspired to cause the school to flourish, and eventu-

ally crossed the great waves to far off China. He travelled

around there, observing the style of zen both east and

west of the Che river," seeing their halls and rooms and

what was in them; he drew pictures of everything and

came back. Ejo greeted him joyfully and abdicated his seat

as abbot of the monastery to him. The master Gikai

opened the hall and expounded the teaching, causing the

school of Eihei to prosper greatly.Later in life he changed Daijo teaching temple in Kaga

into a zen monastery and dwelt there. The master was re-

spectful and solemn in dealing with the community; his

teaching style was most lofty, and everywhere they looked

up to him, calling him the reviver of the To succession.At the end he beat the drum and announced to the

community that he had entrusted the teaching to [okin. He

also explained the process of conceiving the determination

for enlightenment and travel for study. Finally he wrote a

verse:Seven upsets, eight downfalls, ninety-one years

Reed flowers covered with snow,

Day and night the moon is full.

NOTES

1. This scripture has long been popular in Chinese chan circles,

but Dogen did not approve of it.2. This is a saying taken from the Saddh armapundarikosurra, the

Lotus scripture, the section on methods of guidance.3. This is from the sayings of Baizhang; it also appears in

Wumenguan (Mumonkan) 2.4. These are stories involving a shift, a point of transformation,

activation, discriminating knowledge; these are given to students

after they have passed through sayings such as "No," or just sit-

ting with no thought or understanding.5. This can mean he fully realized the import and application of

the teaching, but it also seems to have come to mean the personal

encounter in which not only are the perspective of teacher and

disciple merged, but an explicit design or illustration is articu-

lated, even using sometimes cryptic ancient zen writings as a

basis, as a seal of the transmission of the oral tradition of the

lineage.6. This is the central coastal area of eastern China, containing

large urban centers of the Sung dynasty, and large public monas-

teries.

Jokin of Eiko

The zen master's initiatory name was Jokin; he was styled

螢山紹瑾 Keizan Jōkin (1268–1325)

Keizan. He was entitled Zen Master with Enlightened

Compassion; this was a posthumous title granted by the

emperor of the southern court. He was from Etchu, and his

lay surname was Kubara.When he was a child he took master Ejo as his teacher

and shaved his head and put on monk's clothing. When

zen master Gikai succeeded to the seat to lead the commu-

nity at Eihei, the master Jokin served as Gikai's personal

attendant, taking care of his robes and bowl. One time

when he entered Gikai's room, Gikai asked him, "Can you

bring forth the ordinary mind?" As [okin tried to say

something, Gikai hit him right on the mouth; Jokin was at

a loss, and at this point his feeling of doubt blazed. One

night as he was in the hall sitting in concentration, he

suddenly heard the wind at the window and had a power-

ful insight. Gikai deeply approved of him. After a long

time Gikai entrusted the teaching to Jokin, who finally

succeeded to the seat at Daijo, having had for years the

complete ability, transcending the teacher.When he reopened the Eiko monastery of eternal light

and lived there, lords and officials came to him when they

heard of him; his influence was greatest in his time. One

day he said to his student Meiho, "On the spiritual moun-

tain there was a leader of the assembly (Mahakasyapa)

who shared the teaching seat (with Shakyamuni Buddha);

at Caoqi there were leaders of the assembly who shared

the teaching. Here at Eiko today I too am making an as-

sembly leader to take part in teaching." Then with a verse

he bestowed the robe - "The flaming man under the lamp

of eternal light - shining through the aeon's sky, the at-

mosphere is new. The jutting Peak of Brilliance* is hard to

conceal; his whole capability turns over, revealing the

whole body."Thereafter the master Jokin never drummed his lips

(spoke much) to the assembly; late in life he changed the

disciplinary monastery Soji into a zen place and stayed* This refers to Meiho.

there. After a long time at it , he had had enough of templ e

business, so he gave the abbacy to Gazan , extending a col-

lateral branch of the teaching. The master Jokin always

liked to travel, so when he had retired from his duties he

wandered around with a broken rainhat and a skinny

cane , meeting people wherever he went, and crowds of

people submitted to him.

Soseki of Soji

峨山韶碩 Gasan Jōseki (1275-1366)The zen master's initiatory name was Soseki; he was styled

Gazan. He was from Noto prefecture, and his lay surname

was Minamoto; he was a descendant of the great councillor

Reizei. His mind was exceptionally keen, and his clear

countenance was extraordinary.As a youth he gave up lay life and climbed right up to

Mount Hiei, where he set up an altar and received the pre-

cepts. He often went to lectures and studied thoroughly

the essentials of the school of Tendai. When he happened

to meet zen master Keizan at Oaijo monastery, Keizan saw

at once that he was a vessel of truth, so he said to him, "A

fine vessel of dharma; why don't you change your vest-

ments and investigate zen?" The master Gazan said, "I

have a mother and I fear she would lack support (if I did

so)." Keizan said, "In ancient times Sanavasa gave up a

whole continent to enter our school; how can you neglect

the way of the greatest teaching for a petty mundane

duty?" Then he took off his outer robe and gave it to Ga-

zan, who joyfully accepted it with a bow.Then he went along with Keizan when he moved to Soji

monastery. He was wholehearted and sincere at all times,

never once straying. One day when Keizan got up in the

hall to speak, the master Gazan came forward from the as-

sembly and asked, "Why is it hard to speak of the place

where not a breath enters?" Keizan said, "Even speaking

of it does not say it." The master had a flash of insight; as

he was about to open his mouth, Keizan said, "Wrong."

Scolded, Gazan withdrew; after this his spirit of determi-

nation soared far beyond that of ordinary people. One

night as Keizan was enjoying the moon along with Gazan,

he said, "Do you know that there are two moons?" Gazan

said, "No." Keizan said, "If you don't know there are two

moons,* you are not a seedling of the To succession."At this the master increased his determination and sat

crosslegged like an iron pole for years. One day as Keizan

passed through the hall he said, " 'Sometimes it is right to

have Him raise his eyebrows and blink his eyes; some-

times it is right not to have Him raise his eyebrows and

blink his eyes.' "** At these words the master Gazan was

greatly enlightened. Then with full ceremony he expressed

his understanding. Keizan agreed with him and said, "Af-

ter the ancients had gotten the message , they went north

and south, polishing and chipping day and night, never

complacent or self-conceited. From today you should go

call on (the teachers) in other places."Gazan bowed and took his leave that very day. At all the

monasteries he visited he distinguished the dragons from

the snakes.*** After a long time of this he eventually re-

turned to look in on Keizan. Keizan welcomed him joyfully

and said, "Today you finally can be a seedling of the To

succession." The master Gazan covered his ears.Keizan said, "I am getting feeble and am depending on

a hand from you to hold up a broken sand bowl;" then he

transmitted the teaching to him. After the master had re-

ceived it, he led the community at Soji. The monastery

regulations were fully developed, modeled on the strict

rules of Tiantong. Before long people from all walks of life

came like clouds. Always surrounded by thousands of

people, Gazan greatly expounded Soto zen.* The moon is the symbol of reality. Traditionally 'middle path'

buddhism provisionally distinguishes two levels of reality, con-

ventional (social) and ultimate ('emptiness').** This is a saying of Shitou.

*** Dragons are great meditation adepts; snakes are those that

resemble 'dragons' but aren't really; that is, Gazan saw who were

the genuine knowers and who were the imitations.Gazan Soseki had twenty-five enlightened disciples to

whom he transmitted the Dharma; each spread the teach-

ing in one region, and the influence of the school spread

all over the country. At the end of his life he had Taigen

inherit his seat, and also entrusted Tsugen with the sceptre

of authority of the school. After he had imparted his last

instruction to his various disciples Mutan, Daitetsu, Hobo,

and the rest, he rang the bell, chanted a verse, and died .His verse said,

Skin and flesh together

Ninety one years.

Since night, as of old,

I lie in the yellow springs of death.

Jakurei of Yotaku

通幻寂霊 Tsūgen Jakurei (1322-1391)The zen master's initiatory name was Jakurei; he wa s

styled Tsugen. He was from Kyoto. He was orphaned as a

child and was raised by his grandmother. He saw that he

was physically unfit for worldly occupations, and climbed

Mount Hiei to have his head shaved. His mind and appear-

ance were outstanding and brilliant; he could understand

scriptures at a glance. He deeply cultivated and refined the

teachings (of Tendai buddhism) of cessation and insight

He had some doubt and set his mind on that which is

beyond the teachings; so he left (Hiei) and called on zen

master Gazan at Soji.Gazan asked, "Where have you come from?" He said,

"Mount Hiei." Gazan said, "What do you seek?" He said,

"I have doubted the teaching of cessation and insight for a

long time." Gazan said, "Don't indulge in imagination!"

Tsugen's feeling of doubt flared up all the more, to the

point where he forgot about eating and sleeping. Gazan

knew he was a vessel of Dharrna. and questioned him

closely about the saying about shedding body and mind.One morning the master Tsugen was suddenly en-

lightened and said, "Old teacher, don't fool people!"

Gazan said, "What truth have you seen?" He said, "Riding

backwards on the buddha shrine, going out the main

gate." Gazan agreed with this. After that Tsugen studied

with Gazan for a very long time and understood all the

stories of past and present.When the master Tsugen received the robe symbolizing

the faith, he expounded the teaching at Yotaku and

Ryusen monasteries; his fame in the way was honored

beyond the seas, and crowds of people came and went

ceaselessly. At that time the emperor Goenju of the Oan

era sent down an edict granting Tsugen authority over the

whole school throughout the land; because of this, the

standards of Soto zen were strict everywhere.The master was most high minded and didn't speak

with people . He always stayed in one room and forgot all

about society. One day he had a slight illness; he rang the

bell and told the assembly, then admonished them,

"People, you should end all entanglements and concentrate

on understanding your own affair. On the other side,

throwaway useless words and letters; on this side, slough

off evanescent honor and profit - wherever you are, be

clean and free and you may be true seedlings of the To

succession. Otherwise, you are not my disciples."He asked for a brush and wrote a verse saying,

Coming and going in this world,

A full seventy years;

Here where I turn around,

My feet tread upon the heavens.Having written this, he died sitting peacefully.

Emyo of Saijo

了庵慧明 Ryōan Emyō (1337-1411)The zen master's initiatory name was Emyo; he was styled

Ryoan. He was from Sagami prefecture. When he was

young he left the world and went to Kencho monastery.

He was great by nature and people who saw him cowered.

It came to pass that he thought to himself, "In the investi-

gation of zen, if one does not meet an enlightened teacher,

one may get sidetracked and waste effort and trouble. I

hear zen master Tsugen, the sixth generation of Eihei, has

the power to help people pull out the nails and stakes.

Days and months fly by; why stick by a stump* and re-

main in a little byway?" So he set out to Yotaku.Tsugen's manner of teaching was extremely remote and

inaccessible; a lot of people who came were not allowed to

enter his room, and often had to "stay with their hats on"

for years. When the master Ryoan first got there, Tsugen

asked, "Where have you come from?" He said, "Sagami."

Tsugen said, "How far was the journey?" He said, "Over

three hundred miles." Tsugen said, "How many sandals

did you wear out?" He said, "I lost count." Tsugen hit

him on the head and said, "I don't keep any rice bags like

this around here." The master was greatly enlightened at

these words and immediately expressed his understanding

in verse. Tsugen gave him the seal of recognition and al-

lowed him to enter the room. The whole community was

amazed.* This refers to a well known story of a man who saw a rabbit

run into a stump and die, so he waited by the stump to catch

another rabbit; this exemplifies someone who clings to a method

or teaching, especially to verbal formulations, in hopes of attain-

ing enlightenment.The next day Tsugen said in the teaching hall, "There is

an iron-nose ox here who entered the room last night and

had it out with this old monk." Then he got down from

the teaching seat and put master Ryoan in the senior

monk's seat. After a long time in that position, Ryoan re-

ceived the robe of faith and eventually returned to Sagami.

He began to teach at Saijo, and produced two people of

like mind, Taiko and Mukyoku, and the influence of the

Soto school flourished in eastern Japan.Ryoan used to say to the community, "Zen folk, if you

want to illumine your selves, you must succeed in doing

so in the midst of all kinds of confusion and upsets; don't

make the mistake of sitting dead in the cold ashes of a

withered tree. When I was in the community of my late

teacher, I lost my nostrils at the blow of a staff and have

not found them to this day."

Myoshu of Daiji

大綱明宗 Daikō Myōshū (?-1437)The zen master's initiatory name was Myoshu, he was

styled Taiko; there is no record of his family name. He

first called on Ryoan Emyo at Saijo and asked, "What is an

entry for the student?" Emyo said, "Come here." The mo-

ment Taiko approached, Emyo grabbed him and pushed

him away, saying, "There is no way of entry for you here."

As Taiko got up, the feeling of doubt suddenly arose; day

or night he couldn't put it off.Emyo knew secretly that Taiko was a vessel of dharma,

and subsequently drove him out of the temple on the pre-

text that he had broken the rules. Taiko felt no resentment,

but secretly borrowed a room near the monastery and hidthere. For six years he was never forgiven, and just sat

facing a wall day and night. His meditation work became

increasingly refined, till he got to the point of forgetting to

sleep or eat. One day as he stood beside a cowpen he sud-

denly had an insight; he immediately went to the abbot's

quarters with full ceremony. Emyo hollered at him, "Who

gave you permission to come inside the temple?" He said,

Here an entry is wide open." Emyo laughed and said "A

thief has broken down my door." The master bowed.'Thereafter the master Taiko served as Emyo's personal

attendant, gomg deeper into the mystery every day. Late

in life he began to teach at Daiji monastery, and before

long his fame spread far and wide. The master was austere

with the community, and never carelessly wasted even a

cup of water. He cooked rice and sorted vegetables himself

- people saw he had the will to lead a community, and

they stayed there; there were never less than a thousand

people surrounding his teaching seat.Eventually Taiko "distributed the wellspring" of zen to

fill twelve streams. On one occasion when he had a slight

illness he beat the drum to call the community. When

everyone had assembled, the master said, "My teaching is

come to an end; I am making a bequest to you;" then he

raised his staff, shouted once and died standing.

Sosan of Saisho

吾寶宗璨 Gohō SōsanThe zen master's initiatory name was Sosan; he was styled

Goho. It is not known where he was born. As a man he

was naturally good and wise and whenever he spoke it

was something unusual. When he was fifteen he was sin-

cerely bent on investigating zen; at that time he used to

visit zen master Taiko at Daiji monastery; every time he

asked about the great matter, but Taiko did not reply at all

- he only said, "Understand on your own." For six or

seven years he did not teach him anything particular.One morning as the master was at home sweeping up,

his broom hit a rock and broke; he suddenly had insight.

He went directly to tell Taiko about it , and Taiko acknowl-

edged it. Subsequently Goho gave up lay life and was or-

dained, and served as the rice cooker. He was always pure

and true, and never lay down.One morning as Taiko passed by the kitchen and saw

the master washing rice and putting it in the pot he asked,

"The pot is made of iron, the rice is made of grain; what

does this show?"* The master said, "Let the pot be made

of iron , let the rice be made of grain," then he splashed

water on the ground. Taiko deeply approved of him, and

gave him the seal of recognition, predicting, "Our school

will prosper with you; do not speak easily." Then he gave

him the robe of faith, which the master accepted with

bowed head and left.Later Goho began to teach at Saisho and greatly ex-

pounded the Soto school. He said, "The bamboo of the

southern groves, the wood of the northern lands; the vege-

tables of the east garden, the wheat of the west field; these

are the real livelihood of patchrobed monks; how do you

people understand yourselves?" After a long pause he

said, "Just stretch out your legs on the long beach and

sleep in peace; just have no concerns at all. If you are fel-

lows who talk in your sleep with your eyes open, I'll give

you thirty blows of the staff." Then Unshu came forward

from the assembly and said, "You have already tasted a

score of blows, teacher!" The master laughed aloud and

got down from his seat.* 'what' here is literally 'what side,' meaning 'this side' the

mundane, or 'that side,' the transcendental.

Soryu of Kogon

雲岫宗龍 Unshū SōryūThe zen master's initiatory name was Soryu; he was styled

Unshu. He was from Izumo, and his family had been

Shinto priests for generations and were wealthy. Once

when he was a boy he happened to see a frog die as he

crossed by a field with his father; he asked, "Why can't

the frog jump?" His father said, "It's dead." He said, "Do

people also die?" His father said, "Yes." He said, "How

can it be avoided?" His father said, "I have heard that one

who understands buddhism can escape it." He said, "I

want to understand buddhism; how can I do so?" His

father considered him unusual and thought that the boy

was not ordinary and his determination could not be

changed, so he put him in Gakuen temple and had him

leave home and society (and become a monk).Before he had reached the age of fifteen he determined

to study zen; he travelled all over seeking certainty. Finally

he called on master Sosan at Saisho; his expression of his

state and his actions were fitting, and Sosan granted him

the position of second-ranked monk and secretary. He

studied with Sosan for years and intimately attained the

mind seal. Later in life he began to teach at Kogan monas-

tery; the true line of the To school continued unerring.One evening he called his disciple Bun' ei to come to his

room and instructed him, "Our path is transmitted by way

of four kinds of guest and host: sometimes absolute, some-

times relative; sometimes both absolute and relative are il-

lumined together, and sometimes absolute and relative

both disappear." Then he poked the air with his finger and

said, "This point is neither relative nor absolute; the bud-

dhas and patriarchs since time immemorial cannot grasp

it. Later on you will have broken thatch to cover your

head; don't accept people too easily. I won't be around

long." Then be bequeathed to him the robe and the teach-

ing, wrote a verse, announced his illness and died after

three days.

Bun'ei of Tennei

一華文英 Ikke Bunei (1425-1509)The zen master's initiatory name was Bun'ei; he was styled

Ikke. He first called on zen master Unshu at Kogan; as

soon as Unshu saw him, he knew in himself that he was a

vessel of Oharma. Unshu sent Burt'ei to work as cook. The

master Buri'ei was completely earnest in his daily ac-

tivities. One day as Unshu passed by the kitchen he en-

countered the master sorting vegetables by himself. Unshu

said, "How long have you been here?" He said, "Over a

year." Unshu said, "Outside of sorting vegetables and

washing rice, what work do you do?" He said, "I work at

meditation." Unshu said, "What is the aim of your medita-

tion?" He said, "1 want to become a budd ha." Unshu said,

"What is the use of being a buddha?" Bun'ei was stirred

up by this; he increased in determination and didn't sleep

day or night.Once it happened that when Unshu was in the teaching

hall a monk asked, "What is the place where a patchrobed

monk comes forth?" Unshu said, "Blow on willow fuzz

and hairballs fly; when the rain hits the flowers, yellow

butterflies fly." The master Bunei, standing by, was set

free. That evening he went to the abbot's quarters in full

ceremony; Unshu said, "The vegetable picker has finished

with the great matter." The master bowed. After this he

attended Unshu personally, continuing to inquire with

utmost concentration.When Unshu finally died, the master began to teach at

Tennei. A monk came to call and asked, "What is the mas-

ter's family style?" The master said, "On the meditating

shadow the shoulders are as thin as bamboo; the spirit of

the way is grand and solitary as a pine. "The monk asked,

"Suppose a guest comes; then what?" He said, "The tea is

warm in the broken pot - you should drink it; the fra-

grance is gone from the cold oven - I am tired of cook-

ing."The master Bun'ei was a simple and direct man and

didn't like ostentation; it was impossible to be familiar

with him.

Koken of Bansho

無敵高健 Muteki KōkenThe zen master's initiatory name was Koken; he was styled

Muteki. It is not known where he was from. He happened

to visit zen master Bunei at Tennei; Bun'ei liked the mas-

ter's simplicity and genuine sincerity. Their words and ac-

tions met together like a needle and a seed." The master

then stayed and went back to the hall; he wrapped up his

staff and bowl himself, hung them high on the wall and* The image of needle and seed meeting is often used for the-

rare occasion of meeting of true master and true disciple.sat. Except for meals of gruel and rice at dawn and mid-

day , and for answering the calls of nature, he never left his

seat. Winter and summer alike he only wore a single robe;

even in severe cold and muggy heat he never put on any-

thing more or took anything off. He stayed for twenty

years as though it were but a single day.One evening Bun'ei called the master to come to him ; he

raised the robe of the teaching and said, "This was old

Unshu's: I received it there by sorting vegetables and

washing rice for the community. Now I am pressed for

time and want to impart it to you; can I?" He said, "I am

not such a man." Buri'ei said, "I esteem your not being

such a man. Go away this very day, to where there are no

tracks, pick out a man of the way and transmit it to the

succeeding generation - do not let our teaching be cut

off." Then he handed it over; the master assented.After that Koken built a hut at the foot of Mount Fuji

and lived there; he called it Bansho, "Myriad Pines." He

shut off the road to the world and didn't cross the

threshold of the gate for another twenty years. He wrote a

poem,Since coming to this reed hut

I have never looked for human hearths.

At noon I gather forest fruits,

In the evening I boil spring water.

Sewing clouds together, my cold patchwork robe is thick;

Gathering leaves, my old seat is tranquil.

The green and yellow colors beyond the eaves

Remind me of the passing year.Late in life, after he entrusted the teaching to Eiko, he

burned his hut and went away to no one knows where.

Eiko of Choan

受天英祐 Shūten EiyūThe zen master's initiatory name was Eiko; he called him-

self Jutenmin. He was from Bungo prefecture. He left soci-

ety as a youth and always concentrated on the matter per-

taining to his own self. When he was fifteen he went

traveling; at every monastery he went to he was praised

and considered extraordinary. He called on over thirty

teachers and understood the manner and character of all of

them.One day as he was passing through Suruga on his

travels he happened to hear that zen master Koken was

living in a hut below Mount Fuji. The master thought, "A

monk travels in order to meet an enlightened teacher; why

hesitate to go seek him out?" So he went looking for Ko-

ken, traveling ten difficult miles over the banks of rushing

streams and past withered tree crags, finally reaching him.When Koken saw Eiko arrive, he sat facing the wall in

meditation . The master Eiko went up behind him, bowed

and pleaded, "A disciple has come ten miles expecially to

pay obeisance to you, teacher; please be so compassionate

as to face me." Koken didn't pay attention to him. The

master said, "If you don't face me, I'll beat you to death."

Koken still didn't turn around; the master Eiko knew he

was a real man of knowledge. Then he thought up a ploy;

he put his bundle under his arm and left - but once he

was outside the gate he secretly returned and silently

watched from behind the fence for Koken to come out of

stillness. Koken, not realizing he had fallen for Eiko's

scheme, eventually got up and went out; Eiko suddenly

came out from behind the fence, whereat Koken, startled,

rushed back inside. Eiko followed him and asked, "What

is buddhism in the mountains?" Koken said, "From the

beginning of the valley stream to the end, water is still

water; north of the hut, south of the hut, mountains are

mountains." Eiko believed and submitted to him without

reservation; he bowed with full ceremony and pledged to

wait on Koken, drawing water and gathering fruit. Day

and night he served him closely for twelve years.One day Koken said to Eiko, "I have a patchwork robe,

coming apart at the seams, which weighs a thousand

pounds; if you want to bear it, you must use all your

strength in your arm. I am going; take it away." Then he

gave the robe to Eiko. The master Eiko tearfully accepted it

with a bow. Late in life, because of the insistent request of

donors, he began to teach at Choan; crowds of people

came to him from all over.Eiko always taught the community, "In investigating zen

it is necessary to meet an enlightened teacher; once you

meet an enlightened teacher, you must focus your mind

undividedly for months and years. If you casually wear out

sandals traveling over river and lake, when will you ever

be done?"

Gensaku of Tocho

龍湫玄朔 Ryūshū GensakuThe zen master's initiatory name was Gensaku; he was

styled Ryoshu. Nither the circumstances of his birth nor

his early studies are recorded. When he was traveling he

heard of zen master Eikos fame in the way and went spe-

cially to call on him. Eiko assigned him to attend to

(Eiko's) cloth and bowl; he always worked earnestly and

investigated thoroughly and carefully. One day Eiko tested

him with the saying about the ox going through the win-

dow lattice:" the master was at a loss - Eiko said , "If you

study zen in this way, you ' re just wasting food

money. " At this the master aroused his determination; he

was stirred up all the time and his mind was uneasy - so

he went before the buddha image and vowed, "As long as

I have not clarified the great matter, I will not eat or drink

at all." Nothing had touched his lips for over ten days

when he happened to hear a fellow work monk reading

the record of Dogen's sayings at Eihei; when he got to the

point where it says, "the red heart bared entirely, who can

know? What a laugh, the lad on the way to Huangmei,"**

he was suddenly greatly enlightened.After that he never left Eiko's side and eventually suc-

ceeded to the seat at Choan, where the whole community

gladly submitted to him. He was respected all over in his

time for his practice of the way.The master said, "In one there are many, in two there is

no duality - how do you reckon the phrase in between?

Last year was austere, with neither rice nor wheat; this

year is rich with vegetables and fruit."Later he opened Tocho monastery and moved there; the

patrons and the community submitted to him just as when

he was at Choan.* Wuzu Fayan said, "It is like an ox going through a window

lattice; his head, horns, and feet have all passed through - why

can't the tail also pass?" This famous koan is in the Mumonkan.** The lad going to Huangmei is Huineng , the future sixth pa-

triarch of zen in China on his way north to Huangmei to see the

fifth patriarch Hongren.

Zenban of Ankoku

天翁全播 Tennō ZenhanThe zen master's initiatory name was Zenban; he was

styled Teno. He was born in the Unno clan in Shimano.

When he was young he was gentle and kind, always smil-

ing. He was never heard to cry, but he never spoke, either;

people in his village thought he was mute . He first spoke

when he happened to see an image of a buddha. His par-

ents jumped for joy; they asked him, "You can speak! Why

have you been silent all these years?" He said, "As I heard

ordinary converations, it was mostly common vulgarities;

that's why I didn't speak." His parents were startled and

thought he was strange; eventually they allowed him to

leave home.While he was travelling to study zen, everyone esteemed

him as having innate virtue. When he called on zen master

Gensaku at Choan, as soon as Gensaku saw him he knew

he had innate knowledge and didn't need a word of

examination - he assigned him to the senior seat.One evening Gensaku summoned the master and said,

"I am sick, unable to rise; I transmit this misfortune to

you," then he gave him the robe and died. The master

could not but succeed to the seat and dwell there, but he

never assumed his proper position ('the absolute state') as

abbot; he placed a portrait of his late teacher Gensaku in

the abbot's quarters and paid respects to it morning and

evening along with the community for a full year. Because

of this the community of followers really submitted to him.Visitors came all the time. The master always thought of

giving up temple affairs and eventually entrusted the seat

to Enshu and left. Late in life he opened up Ankoku as a

place to finish out his old age; here he wrote,I have longed to hide for ten years;

Finally weaving a reed hut, I can meditate in peace.

Opening the stove, I put a little damp wood in the fire;

Don't mistakenly lift the blind and let my smoke out.

Shutan of Kosho

懷州周潭 Eshū Shūtan (?-1566)The zen master's initiatory name was Shutan; he was

styled Eshu. As a youth he had his head shaved by zen

master Gensaku at Choan and served him as a teacher.

After Gensaku died, he next served as personal attendant

to Ten'o, taking care of his robes and bowl. He attended

these two teachers for over thirty years in all, and delved

deeply into the matter of his own self; Ten'o always called

him a real leaver of home.Once as Ten'o was talking over tea he said to the group,

After a long time Eshu received the teaching and ap-

"Buddhism is like a born enemy; there's no way for you to

approach. If there is a fellow here who can come forth and

tie up the enemy's staff, I will give him a stinking loin-

cloth and let him be abbot." The master Eshu came for-

ward and said, "Everyone has the mettle to challenge the

heavens, but it's better to go the way of the enlightened

ones." Then be brushed out his sleeves and left. Ten'o

pointed around and said, "Without a determination such

as this, how could anyone get my stinking loincloth?"

peared in the world at Choan. The master was a most sol-

emn and upright man; he was so stern it was impossible

to be familiar with him. If anyone broke the rules of the

temple, he would forcibly eject them. He once said, "My

former teacher had me be the master of this temple; how

could I dare take it easy? " Those who heard him were

scared .Later in life he entrusted the teaching to Zokuo and re-

tired to the western hall."* Finally he opened Kosho tem-

ple, where the monastic standards were modeled on those

of Choan.* The western hall is the traditional abode of the retired abbot.

Soden of Ryuko

續翁宗傳 Zokuō SōdenThe zen master's initiatory name was Soden; he was styled

Zokuo. He was from Mutsu prefecture, but his name, or-

dination and early studies are not known. He was a strong

and direct man, extremely vulgar in speech and action; at

all the monasteries he went to he was called Rustic Den.

He was extremely brilliant and very good at poetry, but no

one knew this.One day as he was traveling through Kamakura he hap-

pened to go to Kencho monastery. The followers there, see-

ing the master's rustic crudeness, laughed and made fun of

him, but he sung aloud happily, as if no one were there.

Someone casually composed a verse and showed it to the

master; as soon as he read it the master knew the phrasing

was adequate but the pure essence was not yet ripe. Then

he replied with three verses of his own, and everyone was

so startled they couldn't even clap in appreciation; he got

up and left them.Later he called on zen master Shutan at Choan. Shutan

tested him with the story, "A monk asked Yunmen, 'When

one doesn't produce a single thought, is there any fault or

not?' Yunmen said, ' Mount Everest!'" and had the master

say something about it. The master tried seven or eight

comments, but Shutan didn't agree. Shutan admonished

him, "The way of enlightenment is beyond the reach of

discrimination and emotion; how can it admit of your in-

tellectual calculations or your fancy replies? If you really

want to understand this great matter, you can only do so if

you put down what you have learned by your brilliance."The master now increased his determination, burned all

his notebooks of writings he had studied before, and en-

gaged in investigation with utmost concentration . After

two months he reached the point where he was not aware

of his hands moving or feet walking. One night while he

was walking in the hall, he bumped his head on a pillar

and was suddenly enlightened. He rushed right to the

abbot's quarters; Shutan said, "Rustic Den, your great task

is done." The master bowed.After he had become an abbot, he said to his communi-

ty, "Since I bumped my head on a pillar in my late

teacher's community, the pain has not stopped, even

now." Later he opened Ryuko and Saifuku temples, and

produced two collateral branches of the teaching.

Yohan of Choan

亘天要播 Gōten YōhanThe zen master's initiatory name was Yohan; he was styled

Goten. He came from a Kazusa family of the Taira clan. He

was naturally pure and unattached, uninvolved in the or-

dinary world. He always sat peacefully by the window, re-

laxed and at ease. His parents took him to a local buddhist

temple and let him leave home.He studied and mastered the essentials of the exoteric

and esoteric schools; his thought and conversation was ex-

tremely profound and he was esteemed everywhere for his

lectures on the scriptures. One day he met a zen man who

questioned him closely about meaning, whereupon he re-

pented and shifted his mind to zen meditation. Eventually

he went traveling around and entered Rinzai and Soto zen

monasteries.He called on over one hundred zen teachers in all, be-

fore he finally called on Zokuo at Choan. As Zokuo saw

the master entering the door, he drove him out with loud

shouts. The master stumbled and fell; as soon as he stood

up, he was suddenly vastly and greatly enlightened.

Thereupon he spoke a verse;One shout of the void

And suddenly a corpse revives;

A patch robed monk's gate of entry

Penetrates everywhere.Zokuo gave him the seal of recognition; thenceforth he

changed his robe and followed Zokuo like a shadow or an

echo for seventeen years, day by day going into the myste-

rious profundity.Later, when Zokuo moved to Ryuko, the old worthies at

the temple, along with the patrons, asked the master to

succeed Zokuo at Choan; the master declined, saying he

was not yet refined enough. When they insisted again and

again, he finally assented; those who have the will to lead

a group always have the ability to transcend the teacher.

The master said in the hall, "A golden hen lays an iron

egg; a stone cow embraces a jade calf - here there is some

happening, but how many people can discover their real

potential?"

Shinryu of Choan

大雲神龍 Daiun Shinryū (?-1604)The zen master's initiatory name was Shinryu; he called

himself Big Cloud. No one knew where he came from. He

was a high minded man, given to grandiose talk; every-

where he went he was disliked and ousted by the groups

there . He sought admission to over twenty zen monas-

teries, but none of them allowed him to stay. Finally when

he was about forty he called on zen master Yohan at

Choan; as soon as Yohan saw him he understood Shin-

ryu ' s spirit and admitted him. He tested him with the

story of Zhaozhou checking on the old woman."Shinryu saw that Yohan had the will to lead the com-

munity and deeply believed in him and submitted to him,

with no desire to go anywhere else. He immersed himself

in study with utmost seriousness; he didn't lie down for

years. One day, hauling firewood during general labor, as

he strained to lift a bundle he had a powerful insight; he

hurried to the abbot's room to tell Yohan. Yohan gave him

the seal of recognition and entrusted the teaching and

temple affairs to him.Before long, the patrons and community submitted to

Shinryu, even more than the former teacher; they added

fields and gardens and rebuilt the halls, thereby greatly* There was a woman in north China who lived on the way to

Mt. Wu Tai, a famous holy mountain and place of pilgrimage;

whenever a monk would ask her the way to Mt. Wu Tai, she

would say "Right straight ahead." As the monk set off, she would

say, "A fine priest! He too goes on this way." Someone reported

this to Zhaozhou, the greatest zen master in northern China in

that time; he said, "Wait till I check out that old woman." He

went and asked her the same thing, and she gave the same an-

swer. Zhaozhou said, "I have checked out that old woman for

you." This koan appears in the Wumenguan (Mumonkan) and

Congronglu (Shoyoroku).renovating Choan monastery. Shinryu used to say to the

community, "The important thing in buddhism is to meet

the hammer and tongs of a true teacher; once I heard my

late teacher's instruction, I lost my mouth and ears and

have been cool ever since. Don't pass the years in the

mountains taking it easy."Late in life, after entrusting the teaching to his succes-

sors, he took leave of the community and left - no one

knew where he ended up. The present shrine at Tomikawa

was set up out of respect for his virtue by people of later

times.

Donju of Choan

齡山黁壽 Reizan DonjuThe zen master's initiatory name was Donju; he was styled

Reizan. He was from Awa prefecture. As a youth he left

the dusts of the world and went to Choan monastery to

follow zen master Yohan, where he had his head shaved

and received the precepts. He was extremely brilliant by

nature and fondly occupied himself reading; he studied

widely in the inner (buddhist) and outer (confucian)

classics.One day he sighed to himself, "One who abandons so-

ciety and home regards the fullfillment of buddhahood as

fundamental; who am I, to indulge in reading? The classics

are inexhaustible." At this point he concentrated solely on

meditation. He left to seek certainty everywhere. Again he

lamented, "I have traveled through much of the country

looking for a teacher, wasting my mental energy. What is

the use of traveling around?" Then he returned.Yohan asked him, "How many years have you been

away ?" He said, " Ten years." Yohan said, "Where did you

go?" He said, "Through half the country." Yohan said,

"What did you understand?" Reizan had no reply. Yohan

said , "Give me back the price of your sandals." Reizan

suddenly had insight; afterwards he functioned respon-

sively without trouble, unhindered at all times.When Yohan had Shinryu succeed him, Reizan served as

Shinryu's secretary and kept the same job for ten years.

One day Shinryu said to him, "Since I was cursed by my

late teacher, I will surely grow old in this monastery; now

you too are cursed by me; you should end your life here."

Then he entrusted the teaching to him and left. Then the

patrons and the old worthies combined efforts to keep him

there.The master was always of solitary mien and could not be

presumed upon. Travelers passing through could not be-

come familiar with him for years. At the end he gathered

the community, gave them his last admonitions, wrote a

verse and died sitting. The verse said,Sleeping at night, rushing by day,

For fifty-six years.

When the eyes go blind

I attain this great meditation.

Den'etsu of Choan

The zen master's initiatory name was Den'etsu: he was

長巖田悅 Chōgan Denetsu (?-1610)

styled Chogan. It is not known where he was from. As a

youth he left lay life and entered Choan monastery with

zen master Yohan as his teacher. He was naturally austere

and ascetic; he hauled firewood, drew water, begged for

rice, and made charcoal, for twenty years , working harder

than anyone else. Yohan always called him 'the reincar-

nated ascetic (Mahakasyapa).*Later when Yohan had Shinryu succeed him, Denetsu

served as chief cook for Shinryu, working hard as before.

One day Shinryu, passing the kitchen, found him washing

rice himself; he asked, "What dirt is there in the rice?"

Den'etsu said, "The chaff is endless." Shinryu said, "If it

is endless, how can you wash it away?" Hearing this,

Den'etsu stood transfixed; at that moment secretary Donju,

standing beside Shinryu, said, "Now cook Den'etsu can

really wash the rice." At these words the master was sud-

denly enlightened; he intoned a verse saying,So many years I've washed dirt;

Today I've reached where there is no dust.

The rice filling the bushel

1 see is the original mind.Shinryu joyfully said, "Your teacher is brother Donju; later

you should assist him in the teaching, causing our school

to flourish."Later when Shinryu had secretary Donju assume the ab-

bacy, the master Den'etsu was placed in the senior seat.

After a long time he appeared in the world at Choan;

when he opened the hall and offered incense, he rightly

gave thanks to zen master Donju for the milk of the teach-

ing.* Mahakasyapa, one of the Buddha Gautama's ten foremost

disciples, was most excellent in the practice of asceticism; he is

considered the first patriarch of zen in India , having received the

personal seal of recognition from the Buddha on Vulture Peak

(Grdhakuta, also sometimes 'Spiritual Mountain').

Denjo of Choan

嫡宗田承 Chakushū DenshōThe zen master's initiatory name was Denjo; in the com-

munity he was called the Inheritor of the School as an epi-

thet of praise. There is no record of where he was born.He first called on zen master Denetsu at Choan and

asked, "How should a student use his mind?" Deri'etsu

extended his hands and said, "Bring me your mind."

Denjo was totally at a loss; Den'etsu slapped him on the

face and said, "What mind do you want to use?" At these

words Denjo got the message; thereupon he broke his staff

and stayed there for nineteen years, so earnest that he

never went outside the gate. Then he wrote a verse saying,A thousand miles in search of a teacher

I came to Tomikawa;

With no way to use the mind

At last I meditate in peace.

I don't know how many cushions

I have worn out,

Staying here for nineteen years

At a single stretch.Den'etsu used to say to those around him that Denjo

had attained the true source, so in the community he was

called the Inheritor of the School.* After Denetsu died, the

patrons asked master Denjo to succeed to his seat; the

master declined, saying he had little wisdom, but they in-

sisted again and again, reminding him of the words "he

has inherited my true school." The master shed tears and

couldn't refuse any more. So he set up a portrait of his late

teacher in the abbot's room and bowed to it in the morn-

ing and saluted it at night, just as when he was alive. The

master remained in the 'relative state' for the rest of his

life.*** The word for 'school' or 'sect' basically means 'source.'

** The position of teacher and disciple is likened to 'absolute'

and 'relative.' Denjo never occupied the hojo , or abbot's quarters,

keeping the position of disciple out of reverence for his teacher

Denetsu.

Senteki of Kinryu

巨山泉滴 Kozan Senteki (1561-1641)The zen master's initiatory name was 5enteki; he called

himself The Man of the Ancient Mountain. He was from

Musashi. He left home and society as a boy. A man of

outstanding capabilities, he could see right through

people.He thought to himself, "A monk is someone who is un-

trammelled - why stay by an old tree stump and useless-

ly stick to a small byway?" 50 he became determined to

study zen and went to the famous monasteries in eastern

Japan. Wherever he went he bowled them over with his

talk about the teaching; people recognized him as an ac-

complished student.Finally he called on zen master Denjo at Choan; with

bare feet and head, he pounded rice and hoed the garden

for twenty years at a stretch. One day he heard Denjo say

in the teaching hall, "'Bodhidharma did not come to

China; the second patriarch did not go to India;' herein

there is a silver mountain, an iron wall - when spring

comes the birds call and the flowers bloom." Suddenly he

had insight; he went right to the abbot's room and asked

for approval. Denjo asked, "Later if someone asks about

the vehicle of the school of the To succession, how will

you answer?" He replied, "The white reed flowers have no

different color; white birds alight on a sandbar." Denjo

deeply approved of this; thereupon he warned him, "Our

school will flourish greatly with you, but I fear it will be

hard to find a successor." The master Senteki bowed and

withdrew.When Denjo died he inherited his seat and appeared in

the world at Choan; before long his fame stirred the

monasteries. At that time, the prime minister Hidetada,

hearing of the master's fame in the way, made offerings to

him in Edo (Tokyo), the capital city; the master talked

about the teaching for the minister; delighted, the minister

presented him with rare silks and saw him back to the

mountain. Later the chancellor Toshitsune had a big zen

monastery built at Kanazawa, which he named Tentoku,

'Heavenly Virtue.' As he was looking for a sage to be

abbot there, he asked prime minister Hidetada, who rec-

ommended that he invite the master Senteki to dwell

there. The chancellor sent some knights to urgently invite

him, but the master did not reply. At this point the prime

minister himself told the master that the chancellor's re-

quest was sincere; the master could not refuse, and after

all went to begin teaching there. He greatly revived the

Soto school, and people came from all over the country;

the names in the monastery register numbered over five

thousand.A monk asked, "What is the master's family style?" He

said, "Eating meat, cursing Shakyamuni, drunk on wine,

beating up Maitreya."The master was basically simple and did not like finery

and ostentation. He kept an old horse which he used in-

stead of a carriage; people laughed at him, but he went his

own way. Once he had a slight illness and realized in him-

self that he would never recover, so he sent his bamboo

sceptre to his disciple Kosatsu at Choan with a note say-

ing, "After I die there will be a man beyond measure who

will cause my way to flourish greatly. Hand this noseless

black snake to him in my stead as a token of surety." After

writing this he died sitting upright.

?

鉄心道印 Tesshin Dōin (1593-1680)

Guon of Kinryu

龍睡愚穩 Ryūsui Guon (?-1688)The zen master's name was Guon; he was styled Ryusui.

He called himself by a different name, 'The Old Man of

South Mountain.' He was from Kaga prefecture. As a youth

he had his head shaved at Josho temple in his native prov-

ince. He was naturally open and kind; his face never

showed any anger, and all who saw him felt at ease with

him.During his traveling days he called on seven or eight

teachers and understood their manners and character;

there was no difference in their teachings. Sure of himself,

he appeared in the world at Sosen and Ryumon monas-

teries, giving instructions on request to the groups there

for five to seven years, gaining the status of an abbot.One night the master thought, "If one considers a little

bit to be enough in the investigation of zen, perhaps there

may be something one still has not learned. I hear that zen

master (Ingen) Ryuki of Obaku has come from China to

Japan and is staying in Nagasaki; a perfect man is not far

- I should go knock at his mysterious gate." Then he set

out to go there; but though he entered Ingen's room to

seek and inquire, because of the difference in language

there was a lack of communication and he didn't get

through the difficult, confusing points . He just worked by

himself on scrupulous refinement of meditation, but even

after three years had passed he still had found no way of

entry. He lamented, "My affinity with buddhism in this

life is not yet ripe - what is the benefit of exerting mental

power in the wrong way?" so he took his leave and de-

parted.At that time the abbacy of Tentoku monastery was vac-

ant, and the patrons and community there invited the mas-

ter, who stayed there, going along with circumstances .

One morning when he went into the shrine to bow before

the buddha image, to the east he saw the sunlight shining

on the tree branches; as he suddenly moved his eyes his

insight opened. Thereupon he spoke a verse;For thirty years I have expended my spirit in vain;

Sweeping away useless dust instead became dust itself.

Raising my head, it meets my eyes, without any obscurity -

Myriad forms are especially new.The master also thought, "Realization without making sure

of right and wrong is of dubious benefit." Then he led his

followers to call on zen master Kosatsu at Choan. As soon

as Kosatsu saw him, he received him with an individual

chair , and entrusted the teaching to him according to his

late teacher's will. The master bowed and accepted it, then

returned to his temple.Before long both lay people as well as monks and nuns

gathered there like clouds, just as Senteki had foretold.

One day as the master was going to teach in Kyoto, he

passed by Mt. Obaku on the way and went to see zen

master Ingen Ryuki again; Ryuki greeted him joyfully and

burned incense in a special censer. The next day they had

a meeting of minds and Ryuki presented him with a verse:Wrapped up, carefully stored,

When it is let out in response to the situation

It is totally new.Zen master Shoto of Zozan, who was there at Ryuki's side,

had a verse which said,An iron forehead, a copper crown -

I am glad of this chance meeting;

With tracks like the wind of lightening feet,

He expresses our affinity in action.In 1670 the master saw me, Geppa Doin, at Kanzan; I

met him with proper respect and questioned him closely

about this matter. Our actions and words were in mutual

accord. As I was about to go, the master took my hand and

said, "The time is come; don't keep your hands in your

sleeves (inactive)." Then I knew for the first time I had a

teacher.

End of Biographical Extracts of the Original Stream

In: Timeless Spring, A Soto Zen Anthology,

Weatherhill / Wheelwright Press, Tokyo - New York, 1980, p. 175.

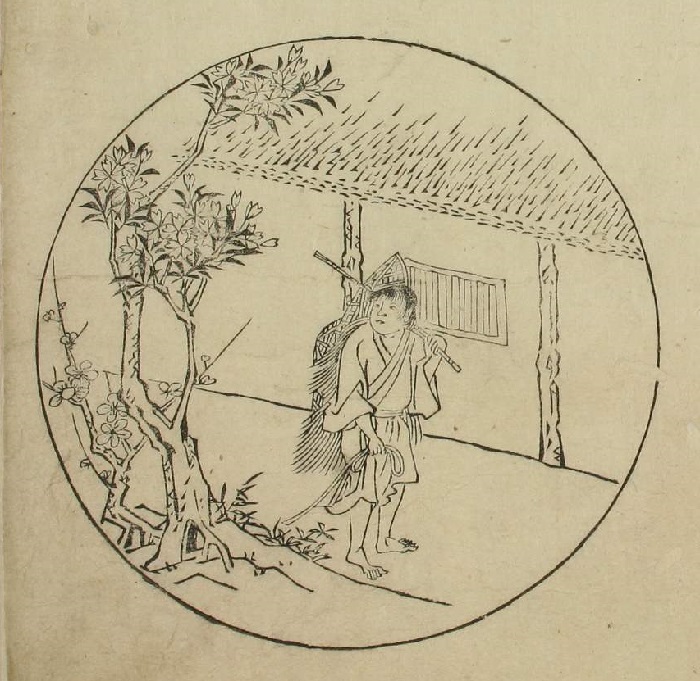

[うしかひ草] Ushikaigusa

by 月波老人 Geppa rōjin [撰] aka 月波道印 Geppa Dōin (1637-1716)

12 illustrations by 湖南隠士観海 Konan inshi kankai [画]

寺町三条下町(京都) : 西田床兵衛, 寛文9[1669]

Teramachi sanjō sagaru machi (Kyōto) : Nishida Shōbee

1冊 ; 26cm

https://www.wul.waseda.ac.jp/kotenseki/html/he13/he13_04182/index.html

https://web.archive.org/web/20140615163902/http://h-kishi.sakura.ne.jp/kokoro-584.htm

<『うしかひ草』の12の段階>

1、「こころをおこす」

2、「家をいづる」

3、「うしを尋ぬる」

4、「あとを見る」

5、「うしを見る」

6、「うしをうる」

7、「うしをかふ」

8、「うしにのる」

9、「うしを忘るる」

10、「うし人とともに忘るる」

11、「いえにかえる」

12、「いしくらに入る」

禪書うしかひ草 /Zensho Ushikaigusa

禅書うしかひ草

http://www.city.minamiawaji.hyogo.jp.e.ct.hp.transer.com/soshiki/gyokuseikan/h28-ushikaigusa.html

http://dokusume.com/modules/store/index.php?main_page=product_info&products_id=7641

中村文峰著【一般書店に売ってません&「うしかひ草」の解説書は現時点でこの本しか存在していないという、超貴重な1冊!】◆江戸時代初期に仮名草子の体裁を借りて、禅の思想を描いた、知る人ぞ知る名著『うしかひ草』の原本に読み下し文と解説を加えた決定版です。「うしかひ草」とは、「人間各自が本来具有する「仏心」に気付かずにいる人が、ふとした機縁により「仏心」を自覚し悟りに至る段階を、飼牛を見失った少年が牛を尋ねあて、飼い馴らして家に連れて帰る過程に置き換えて書かれた本である。同じく、牛を飼い馴らして家に連れて帰る過程を人間の心に当てはめて解説した『十牛図』という名著も有名ですが、『十牛図』が、10の段階に対して、『うしかひ草』は12の段階で、最初に少年が「こころをおこし」「いえを出る」段階が加わり、1年12ヶ月の自然の景色に当て嵌めて仮名混じり文の文章と挿絵で表わして、江戸時代により一般庶民に親しみやすい形で書かれた、自分自身の心を取り戻すまでの物語です。すでに、『十牛図』の解説書などをお読みの方は、より理会が深まりますし、禅にご興味がある方は、是非一度お読みいただきたい名著です!<『うしかひ草』の12の段階>1、「こころをおこす」2、「家をいづる」3、「うしを尋ぬる」4、「あとを見る」5、「うしを見る」6、「うしをうる」7、「うしをかふ」8、「うしにのる」9、「うしを忘るる」10、「うし人とともに忘るる」11、「いえにかえる」12、「いしくらに入る」