ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

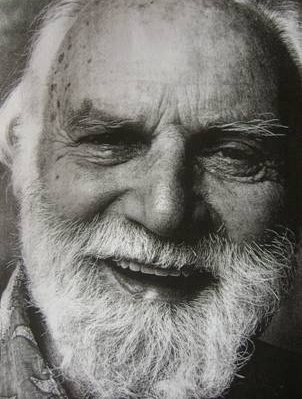

Douglas Harding (1909-2007)

Tartalom |

Contents |

Fej nélkül

—

A Zen és a nyilvánvaló újrafelfedezése On Having No Head (1961) = Híján a fejnek (A fejvesztettségről) |

A Short Biography of Douglas Harding On Having No Head: Zen and the Rediscovery of the Obvious PDF: Zen Experience: A Western Approach |

Harding, D.E., On Having No Head: Zen and the Rediscovery of the Obvious (Carlsbad, CA: Inner Directions ed., 2004). This book, the first widely-read book of over a dozen Harding works, was originally published in 1961 in London by The Buddhist Society with the subtitle “An Introduction to Zen in the West.” It came nine years after his first major work, The Hierarchy of Heaven and Earth: A New Diagram of Man in the Universe (London: Faber & Faber, 1952), acclaimed as “a work of the highest genius” by C.S. Lewis in his Preface. (The Shollond Trust in U.K. in 1998 released an unabridged edition of this earliest work.) The deeply insightful and eloquent Douglas E. Harding (1909-2007) was an unpretentious sage, not affiliated with any religion or sect, who in the 1960s-1970s devised a brilliant set of “Experiments in the Science of the 1st Person” (leading to a book of the same name, publ. by Shollond in 1974), a form of self-inquiry and Self-Realization which he openly shared in workshops and talks for over 40 years, usually without ever charging a penny, whether teaching in his homeland of England or traveling to mainland Europe or the USA. These experiments immediately, clearly, and non-conceptually reveal our Formless and “Form-full” True Nature as the “No-thing-like” Source for all things, the “spacious capacity for all experience,” or the “Host for all guests/phenomena,” to use the language of Dongshan. Harding's experiments like the “pointing finger,” “Big One/little one,” and “the open bag” demonstrably communicate this colorless, shapeless, formless, changeless Source-Reality more accessibly, directly and vividly than any spiritual method, teaching or scripture in existence. All his experiments are well-presented at the www.headless.org website for Harding's life and work, created by his close friend Richard Lang. Many longtime Zen students who've struggled to realize their Original (Faceless) Face via zazen, huatou-investigation, koan-contemplation, or scripture-study can easily awaken to Intrinsic Reality or Open Awareness via Harding's lucid experiments and illuminating words wisely pointing back to our True Nature (closer than thought, closer than the eyeballs), without having to become enmeshed in the rigid and even dysfunctional cult dynamics of too many Zen institutions promoting dubious “enlightenment” under authoritarian “masters.” British author Anne Bancroft, who compiled a few books on Zen (e.g., the well-illustrated Zen: Direct Pointing to Reality, Thames & Hudson, 1979), featured D.E. Harding as one of her chosen sages in Modern Mystics & Sages (London/NY: Paladin, 1978). In addition to the aforementioned early works, see some of Harding's later books such as The Little Book of Life and Death (London: Penguin Arkana, 1988); Head Off Stress (Arkana, 1990); Look for Yourself (UK: Head Exchange Press, 1996; to be republished by The Shollond Trust); Face to No-Face, David Lang, Ed. (Inner Directions, 2000); To Be and Not To Be (London: Watkins, 2002); Open to the Source, Richard Lang, Ed. (Inner Directions, 2005), et al., several available as e-books, along with DVDs/videos at www.headless.org/bibliography.htm.

© Copyright 2018 by Timothy Conway

A SHORT BIOGRAPHY OF DOUGLAS HARDING

by Richard Lang

http://www.headless.org/douglas-harding.htm

Douglas Harding was born in 1909 in Suffolk, England. He grew up in a strict fundamentalist Christian sect, the Exclusive Plymouth Brethren. The ‘Brethren' believed they were the ‘saved' ones, that they had the one true path to God and that everyone else was bound for Hell. When Harding was 21 he left. He could not accept their view of the world. What guarantee was there that they were right? What about all the other spiritual groups who also claimed that they alone had the Truth? Everyone couldn't be right.

In London in the early 1930s Harding was studying and then practising architecture. In his spare time, however, he devoted his energies to philosophy - to trying to understand the nature of the world, and the nature of himself. Into philosophy at this time were filtering the ideas of Relativity. Influenced by these ideas, Harding realized that his identity depended on the range of the observer – from several metres he was human, but at closer ranges he was cells, molecules, atoms, particles… and from further away he was absorbed into the rest of society, life, the planet, the star, the galaxy… Like an onion he had many layers. Clearly he needed every one of these layers to exist.But what was at the centre of all these layers? Who was he really?

In the mid-1930s Harding moved to India with his family to work there as an architect. When the Second World War broke out, Harding's quest to uncover his identity at centre - his True Identity - took on a degree of urgency. Aware of the obvious dangers of war, he wanted to find out who he really was before he died.

One day Harding stumbled upon a drawing by the Austrian philosopher and physicist Ernst Mach (1838-1916). It was a self-portrait – but a self-portrait with a difference. Most self-portraits are what the artist looks like from several feet – she looks in a mirror and draws what she sees there. But Mach had drawn himself without using a mirror – he had drawn what he looked like from his own point of view, from zero distance.

Ernst Mach, Picturing the Visual Field, 1886, from page 15 of his influential book Die Analyse der Empfindungen

(“The Analysis of Sensations and the Relation of the Physical to the Psychical), fourth German edition, Jena, 1903When Harding saw this self-portrait the penny dropped. Until this moment he had been investigating his identity from various distances. He was trying to get to his centre by peeling away the layers. Here however was a self-portrait from the point of view of the centre itself. The obvious thing about this portrait is that you don't see the artist's head. For most people this fact is interesting or amusing, but nothing more. For Harding this was the key that opened the door to seeing his innermost identity, for he noticed he was in a similar condition – his own head was missing too. At the centre of his world was no head, no appearance - nothing at all. And this ‘nothing' was a very special ‘nothing' for it was both awake to itself and full of the whole world. Many years later Harding wrote about the first time he saw his headlessness:

“I don't think there was a ‘first time'. Or, if there was, it was simply a becoming more aware of what one had all along been dimly aware of. How could there be a ‘first-time' seeing into the Timeless, anyway? One occasion I do remember most distinctly – of very clear in-seeing. It had 3 parts. (1) I discovered in Karl Pearson's Grammar of Science, a copy of Ernst Mach's drawing of himself as a headless figure lying on his bed. (2) I noted that he – and I – were looking out at that body and the world, from the Core of the onion of our appearances. (3) It was clear that the Hierarchy, which I was then in the early stages of, had to begin with headlessness, and that this had to be the thread on which the whole of it had to be hung.”

However, Harding did describe his discovery more dramatically in On Having No Head. To read the relevant passage, click here.

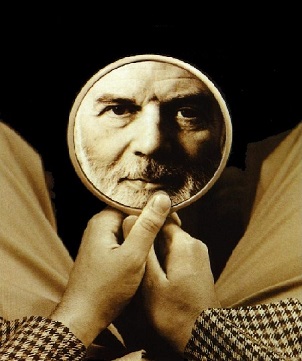

Douglas Harding's self-portrait (On Having No Head, 1961)Following this discovery, Harding spent eight more years working on The Hierarchy of Heaven and Earth. Prefaced by C.S. Lewis who called it “a work of the highest genius”, The Hierarchy was published by Faber and Faber in 1952. (The Shollond Trust published copies of the much larger original manuscript in 1998.) In this book Harding explores, tests and makes sense of his discovery in the broadest and deepest terms. It is not a book for a popular audience, but it is a book that will surely, in time, be recognized as a truly great work of philosophy.

In 1961 the Buddhist Society published On Having No Head – written for a popular audience.

In the late 1960s and 1970s Harding developed the experiments – awareness exercises designed to make it easy to see one's headlessness and to explore its meaning and implications in everyday life.

He died in January 2007, shortly before his 98th birthday.http://www.headless.org/english-welcome.htm

https://www.youtube.com/profile?user=headexchange

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/douglas-harding-436388.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Douglas_Harding

http://www.selfdiscoveryportal.com/gtBioSk.htm#DEH

http://www.raptitude.com/2010/08/the-marvelous-decapitation-of-douglas-harding/

PDF: On Having No Head

Zen and the Rediscovery of the Obvious

by D. E. Harding

First published by The Buddhist Society, London, 1961. Second Edition 1967.

Carlsbad, CA: Inner Directions ed., 2004

https://ia800207.us.archive.org/11/items/OnHavingNoHead-Zen/nohead.pdf

https://www.scribd.com/doc/302568375/Douglas-Harding-On-Having-No-HeadCONTENTS

1 THE TRUE SEEING

2 MAKING SENSE OF THE SEEING

3 DISCOVERING ZEN

4 BRINGING THE STORY UP TO DATE

The Eight Stages of the Headless Way

(1) The Headless Infant

(2) The Child

(3) The Headed Grown-up

(4) The Headless Seer

(5) Practising Headlessness

(6) Working It Out

(7) The Barrier

(8) The Breakthrough

Summary and Conclusion

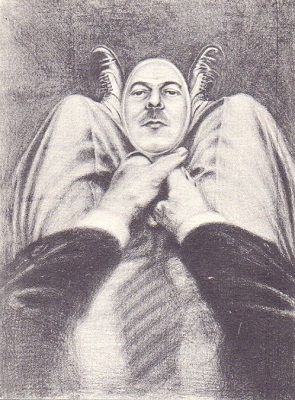

POSTSCRIPTThe best day of my life – my rebirthday, so the speak – was when I found I had no head. This is not a literary gambit, a witticism designed to arouse interest at any cost. I mean it in all seriousness: I have no head.

It was about eighteen years ago, when I was thirty-three, that I mad the discovery. Though it certainly came out of the blue, it did so in response to an urgent enquiry; I had for several months been absorbed in the question: what am I? The fact that I happened to be walking in the Himalayas at the time probably had little to do with it; though in that country unusual states of minds are said to come more easily. However that may be, a very still clear day, and a view from the ridge where I stood, over misty blue valleys to the highest mountain range in the world, with Kangchenjunga and Everest unprominent among its snow peaks, made a setting worthy of the grandest vision.

What actually happened was something absurdly simple and unspectacular: I stopped thinking. A peculiar quiet, and odd kind of alert limpness or numbness, came over me. Reason and imagination, and all mental chatter died down. For once, words really failed me. Past and future dropped away . I forgot who and what I was, my name, manhood, animalhood, and all that could be called mine. It was if I had been born that instant, brand new, mindless, innocent of all memories. There existed only the Now, that present moment and what was clearly given in it. To look was enough. And what I found was khaki trouserlegs terminating downwards in a pair of brown shoes, khaki sleeves terminating sideways in a pair of pink hands, and a khaki shirtfront terminating upwards in – absolutely nothing whatever! Certainly not in a head.

It took me no time at all to notice this nothing, this hole where a head should have been, was no ordinary vacancy, no mere nothing. On the contrary, it was a nothing that found room for everything—room for grass, trees, shadowy distant hills, and far beyond them snow-peaks like a row of angular clouds riding the blue sky. I had lost a head and gained a world.

It was after all, quite literally breathtaking. I seemed to stop breathing altogether, absorbed in the Given. Here it was, this superb scene, brightly shining in the clear air, alone and unsupported, mysteriously suspended in the void, and (and this was the real miracle, the wonder and delight) utterly free of “me,” unsustained by any observer. Its total presence was my total absence, body and soul. Lighter than air, clearer than glass, altogether released from myself, I was nowhere around.

Yet in spite of the magical and uncanny quality of this vision, it was no dram, no esoteric revelation. Quite the reverse; it felt like a sudden waking from the sleep of ordinary life, and end to dreaming. It was self luminous reality for once swept clean of all obscuring mind. It was the revelation, at long last, of the perfectly obvious. It was a lucid moment in a confused life-history. It was a ceasing to ignore something which (since early childhood at any rate) I had always been too busy or too clever to see. It was naked, uncritical attention to what had all along been staring me in the face – my utter facelessness. In short, it was all perfectly simple and plain and straightforward, beyond argument, thought, and words. There arose no questions, no reference beyond the experience itself, but only peace and a quiet joy, and the sensation of having dropped an intolerable burden.

As the wonder of my Himalayan discovery began to wear off, I started describing it to myself in some such words as the following.

Somehow or other I had vaguely thought of myself as inhabiting this house which is my body, and looking out through its two round windows at the world. Now I find it isn't really like that at all. As I gaze into the distance, what is there at this moment to tell me how many eyes I have here – two, or three, or hundreds, or none? In fact, only one window appears on this side of my façade and that is wide open and frameless, with nobody looking out of it. It is always the other fellow who has eyes and a face to frame them; never this one.

There exist, then, two sorts – two widely different species – of man. The first, of which I note countless specimens, evidently carries a head on its shoulders (and by “head” I mean a hairy eight inch ball with various holes in it) while the second, of which I note only this one specimen, evidently carries no such thing on its shoulders. And till now I had overlooked this considerable difference! Victim of a prolonged fir of madness, of a lifelong hallucination (and by “hallucination” I mean what my dictionary says: apparent perception of an object not actually present), I had invariably seen myself as pretty much like other men, and certainly never as a decapitated but still living biped. I had been blind to the one thing that is always present, and without which I am blind indeed – to this marvelous substitute-for-a-head, this unbounded charity, this luminous and absolutely pure void, which nevertheless is – rather than contains – all things. For however carefully I attend, I fail to find here even so much as a blank screen on which they are reflected, or a transparent lens or aperture through which they are viewed – still less a soul or a mind to which they are presented, or a viewer (however shadowy) who is distinguishable from the view. Nothing whatever intervenes, not even that baffling and elusive obstacle called “distance”: the huge blue sky, the pink-edged whiteness of the snows, the sparkling green of the grass – how can these be remote when there's nothing to be remote from? The headless void here refuses all definition and location: it is not round, or small, or big, or even here as distinct from there. (And even if there were a head here to measure outwards from, the measuring-rod stretching from it to the peak of Everest would, when read end-on – and there's no other way for me to read it – reduce to a point, to nothing.) In fact, those colored shapes present themselves in all simplicity, without any such complications as near or far, this or that, mine or not mine, seen-by-me or merely given. All twoness – all duality of subject and object – has vanished: it is no longer read into a situation which has no room for it.Such were the thoughts which followed the vision. To try to set down the first-hand, immediate experience in these or any other terms, however, is to misrepresent it by complicating what is quite simple: indeed the longer the postmortem examination drags on the further it gets from the living original. At best. These descriptions can remind one of the vision (without the bright awareness) or invite a recurrence of it; but the most appetizing menu can taste like the dinner, or the best book about humour enable one to see a joke. On the other hand, it is impossible to stop thinking for long, and some attempt to relate the lucid intervals of one's life to the confused backgrounds is inevitable. It could also encourage, indirectly, the recurrence of lucidity.

In any case, there are several commonsense objections which refuse to be put off any longer, questions which insist on reasoned answers, however inconclusive. It becomes necessary to “justify” one's vision, even to oneself; also one's friends may need reassuring. In a sense this attempt at domestication is absurd, because no argument can add to or take from an experience which is as plain and incontrovertible as hearing middle-C or tasting strawberry jam. In another sense, however, the attempt has to be made, if one's life is not to disintegrate into two quite alien, idea-tight compartments.

* * * *

My first objection was that my head may be missing, but not its nose. Here it is, visibly preceding me wherever I go. And my answer was: if this fuzzy, pinkish, yet perfectly transparent cloud suspended on my right, and this other similar cloud suspended on my left, are noses, then O count two of them and not one; and the perfectly opaque single protuberance which I observe so clearly in the middle of your face is not a nose: only a hopelessly dishonest or confused observer would deliberately use the same name for such utterly different things. I prefer to go by my dictionary and common usage, which oblige me to say that, whereas nearly all other men have a nose apiece, I have none.

All the same, if some misguided skeptic, overanxious to make his point, were to strike out in this direction, aiming midway between these two pink clouds, the result would surely be as unpleasant as if I owned the most solid and punchable of noses. Again, what about this complex of subtle tensions, movements, pressures, itches, tickles, aches, warmths and throbbings, never entirely absent from this central region? Above all, what about these touch-feelings which arise when I explore here with my hand? Surely these findings add up to massive evidence for the existence of my head right here and now, after all?

They do nothing of the sort. No doubt a great variety of sensations are plainly given here and cannot be ignored, but they don't amount to a head, or anything like one. The only way to make a head out of them would be to throw in all sorts of ingredients that are plainly missing here – in particular, all manner of coloured shapes in three dimensions. What sort of head is it that, though containing innumerable sensations, is observed to lack eyes, mouth, hair, and indeed all bodily equipment which other heads are observed to contain? The plain fact is that this place must be kept clear of all such obstructions, of the slightest mistiness or colouring which could cloud my universe.

In any case, when I start groping round for my lost head, instead of finding it here I only lose my exploring hand as well; it too, is swallowed up in the abyss at the centre of my being. Apparently this yawning cavern, this unoccupied base of all my operations, this magical locality where I thought I kept my head, is in fact more like a beacon-fire so fierce that all things approaching it are instantly and utterly consumed, in order that its world-illuminating brilliance and clarity shall never for a moment be obscured. As for these lurking aches and tickles and so on, they can no more quench or shade that central brightness than these mountains and clouds and sky can do so. Quite the contrary: they all exist in its shining, and through them it is seen to shine. Present experience, whatever sense is employed, occurs only in an empty and absent head. For here and now my world and my head are incompatibles, they won't mix. There is no room for both at once on these shoulders, and fortunately it is my head with all its anatomy that has to go. This is not a matter of argument, or of philosophical acumen , or of working oneself up into a state, but of simple sight – LOOK-WHO'S-HERE instead of THINK-WHO'S-HERE. If I fail to see what I am (and especially what I am not) it is because I am too busily imaginative, too “spiritual,” too adult and knowing, to accept the situation exactly as I find it at the moment. A kind of alert idiocy is what I need. It takes an innocent eye and an empty head to see their own perfect emptiness.

* * * *

Probably there is only one way of converting the skeptic who still says I have a head here, and that is to invite him to come here and take a look for himself; only he must be an honest reporter, describing what he observes and nothing else.

Starting off on the far side of the room, he sees me as a full-length man-with-a-head. But as he approaches he finds half a man, then a head, ten a blurred cheek or eye or nose; then a mere blur and finally (at the point of contact) nothing at all. Alternatively, if he happens to be equipped with the necessary scientific instruments; he reports that the blur resolves itself into tissues, then cell groups, then a single cell, a cell-nucleus, giant molecules … and so on, till he comes to a place where nothing is to be seen, to space which is empty of all solid or material objects. In either case, the observer who comes here to see what it's really like finds what I find here – vacancy. And if, having discovered and shared my nonentity here, he were to turn round (looking out with me instead of in at me) he would again find what I find – that this vacancy is filled to capacity with everything imaginable. He, too, would find this central Point exploding into an Infinite Volume, this Nothing into the All, this Here into Everywhere.

And if my skeptical observer still doubts his senses, he may try his camera instead – a device which, lacking memory and anticipation, can register only what is contained in the place where it happens to be. It records the same picture of me. Over there, it takes a man, midway, bits and pieces of a man; here, no man and nothing – or else, when pointed the other way round, the universe.

* * * *

So this head is not a head, but a wrong-headed idea. If I an still find a here, I am “seeing things,” and ought to hurry off to the doctor. It makes little difference whether I find a human head, or an asse's head, a fried egg, or a beautiful bunch of flowers|: to have any topknot at all is to suffer from delusions.

During my lucid intervals, however, I am clearly headless here. Over there, on the other hand, I am clearly far from headless: indeed, I have more heads than I know what to do with. Concealed in my human observers and in cameras, on display in picture frames, pulling faces behind shaving mirrors, peering out of door knobs an spoons and coffeepots and anything which will take a high polish, my heads are always turning up – though more-or-less shrunken and distorted, twisted back-to-front, often the wrong way up, and multiplied to infinity.

But there is one place where no head of mine can ever turn up, and that is here “n my shoulders,” where it would blot out this Central Void which is my very life-source: fortunately nothing is able to do that. In fact, these loose heads can never amount to more than impermanent and unprivileged accidents of that outer” or phenomenal world which though altogether one with the central essence, fails to affect it in the slightest degree. So unprivileged, indeed, is my head in the mirror, that I don't necessarily recognize myself in the glass, and neither do I see the man over there, the too-familiar fellow who lives in that other room behind the looking-glass and seemingly spends all his time staring into this room – that small, dull, circumscribed, particularized, ageing, and oh-so-vulnerable gazer – as the opposite to every way of my real Self ere. I have never been anything but this ageless, adamantine, measureless, lucid, and altogether immaculate Void: it is unthinkable that I could ever have been confused that staring wraith over there with what I plainly perceive myself to be here and now and forever!

* * * *

All this, however clearly given in first-hand experience, appears nevertheless wildly paradoxical, an affront to common-sense. Is it also an affront to science, which is said to be only common-sense tidied up somewhat? Anyhow, the scientist has his own story of how I see some things (such as your head) but not others (such as my head): and obviously his story works. The question is: can he put my head back on my shoulders, where people tell me it belongs?

At its briefest and plainest, his tale of how I see you runs something like this. Light leaves the sun, and eight minutes later gets to your body, which absorbs a part of it. The rest bounces off in all directions, and some of it reaches my eye, passing through the lens and forming an inverted picture of you on the screen at the back of my eyeball. This picture sets up chemical changes in a light-sensitive substance there, and these changes disturb the cells (they are tiny living creatures) of which the screen is built. They pass on their agitation to other, very elongated cells; and these, in turn, to cells in a certain region of my brain. It is only when this terminus is reached, and the molecules and atoms and particles of these braincells are affected, that I see you or anything else. And the same is true of the other senses; I neither see nor hear nor smell nor taste nor feel anything at all until the converging stimuli actually arrive, after the most drastic changes and delays, at this centre. It is only at this terminus, this moment and place of all arrivals at the Grand Central Station of my Here-Now, that the whole traffic system - what I call my universe - springs into existence. For me, this is the time and place of all creation.

There are many odd things, infinitely remote from common-sense, about this plain tale of science. And the oddest of them is that the tale's conclusion cancels out the rest of it. For it says that all I can know is what is going on here and now, at this brain terminal, where my world is miraculously created. I have no way of finding out what is going on elsewhere - in the other regions of my head, in my eyes, in the outside world - if, indeed, there is an elsewhere, an outside world at all. The sober truth is that my body, and your body, and everything else on Earth, and the Universe itself - as they might exist out there in themselves and in their own space, independently of me - are mere figments, not worth a second thought. There neither is nor can be any evidence for two parallel worlds (an unknown outer or physical world there, plus a known inner or mental world here which mysteriously duplicates it) but only for this one world which is always before me, and in which I can find no division into mind and matter, inside and outside, soul and body. It is what it's observed to be, no more and no less, and it's the explosion of this centre - this terminal spot where “I” or “my consciousness” is supposed to be located - an explosion powerful enough to fill out and become this boundless scene that's now before me, that is me.

In brief, the scientist's story of perception, so far from contradicting my naive story, only confirms it. Provisionally and common-sensibly, he put a head here on my shoulders, but it was soon ousted by the universe. The common-sense or un-paradoxical view of myself as an “ordinary man with a head” doesn't work at all; as soon as I examine it with any care, it turns out to be nonsense.

* * * *

And yet (I tell myself) it seems to work out well enough for all everyday, practical purposes. I carry on just as if there actually were, suspended here, plumb in the middle of my universe, a solid eight inch ball. And I'm inclined to add that, in the uninquisitive and truly hard-headed world we all inhabit, this manifest absurdity can't be avoided: it is surely a fiction so convenient that it might as well be the plain truth. In fact, it is always a lie, and often an inconvenient lie at that: it can even lose a person money. Consider, for instance, the designer of advertisements - whom nobody would accuse of fanatical devotion to truth. His business is persuading me, and one of the most effective ways of doing that is to get me right into the picture as I really am. Accordingly he must leave my head out of it.

Instead of showing the other kind of man - the one with a head - lifting a glass or cigarette to his mouth, he shows my kind doing so: this right hand (held at precisely the correct angle in the bottom right-hand corner of the picture, and more-or-less armless) lifting a glass or cigarette to - this no-mouth, this gaping void. This man is indeed no stranger, but myself as I am to myself. Almost inevitably I am involved. No wonder these bits and pieces of a body appearing in the corners of the picture, with no controlling mechanism of a head in the centre to connect or operate them - no wonder they look perfectly natural to me: I never had any other sort! And the ad-man's realism, his uncommon-sensical working knowledge of what I am really like, evidently pays off: when my head goes, my sales resistance is apt to follow. (However, there are limits: he is unlikely, for instance, to show a pink cloud just above the glass or the cigarette, because I supply that piece of realism anyhow. There would be no point in giving me another transparent nose-shadow.)

Film directors . . . are practical people, much more interested in the telling re-creation of experience than in discerning the nature of the experience; but in fact the one involves some of the other. Certainly these experts are well aware (for example) how feeble my reaction is to a film of a vehicle obviously driven by someone else, compared with my reaction to a film of a vehicle apparently driven by myself. In the first instance I am a spectator on the pavement, observing two similar cars swiftly approaching, colliding, killing the drivers, bursting into flames – and I am mildly interested. In the second, I am the driver – headless of course, like all first-person drivers, and my car (what little there is of it) is stationary. Here are my swaying knees, my foot hard down on the accelerator, my hands struggling with the steering wheel, the long bonnet sloping away in front, telegraph poles whizzing by, the road snaking this way and that, the other cars, tiny at first, but looming larger and larger, coming straight at me, and then the crash, a great flash of light, and an empty silence . . . I sink back onto my seat and get my breath back. I have been taken for a ride.

How are they filmed, these first person experiences? Two ways are possible: either a headless dummy is photographed, with the camera in place of the head, or else a real man is photographed, with his head held far back, or to one side to make room for the camera. In other words, to ensure that I shall identify myself with the actor, his head is got out of the way; he must be my kind of man. For a picture of me-with-a-head is no likeness at all, it is the portrait of a complete stranger, a case of mistaken identity.

It's curious that anyone should go to the advertising man for a glimpse into the deepest - and simplest - truths about himself; odd also that an elaborate modern invention like the cinema should help rid anyone of an illusion which very young children and animals are free of. But in other ages there were other and equally curious pointers to the all-too-obvious, and our human capacity for self-deception has surely never been complete. A profound though dim awareness of the human condition may well explain the popularity of many old cults and legends of loose and flying heads, or one-eyed or headless monsters and apparitions, of human bodies with non-human heads, and of martyrs who walked for miles after their heads were cut off - fantastic pictures, no doubt, but nearer than common-sense ever gets to a true portrait of this man, of the first person singular, present tense.

* * * *

My Himalayan experience, then, was no mere poetic fantasy or airy mystical flight. In every way it turned out to be sober realism. And gradually, in the months and years that followed, the full extent of its practical implications and applications, its life-transforming consequences, dawned upon me.

For example, I saw that on two counts this new vision must transform my attitude to other men, and indeed to all creatures. Firstly, because it abolishes confrontation. Meeting you, there is for me only one face - yours - and I can never get face-to-face with you. In fact, we trade faces, and this is a most precious and intimate exchange of appearances. Secondly, because it gives me perfect insight into the Reality that lies behind your appearance, into you as you are for yourself, I have every reason to think the world of you. For I must believe that what is true for me is true for everyone, that we all are in the same condition - reduced to headless voids, to nothing, so that we may contain and become everything. That small, headed, solid-looking person I pass in the street - that one is the apparition which never stands up to close inspection, the heavily disguised one, the walking opposite and contradiction of the real one whose extent and content are infinite: and my respect for that person, as for every living thing, should be infinite too. His value and splendour cannot be overrated. Now I know exactly who he is and how to treat him.

In fact, he (or she) is myself. While we had a head apiece, obviously we were two. But now we are headless voids; what is there to part us? I can find no shell enclosing this void which I am, no shape or boundary or limit: so it cannot help but merge with other voids.

Of this merging I am my own perfect specimen. I don't doubt the scientist who says that, from his observation point over there, I have a clearly defined head consisting of an immense hierarchy of clearly defined bodies such as organs, cells, and molecules - an inexhaustibly complex world of physical things and processes. But I happen to know (or rather, to be) the inside story of this world and every one of its inhabitants, and it completely contradicts the outside story. Right here, I find that every member of this vast community, from the smallest particle to my head itself, has vanished like darkness in sunlight. No outsider is qualified to speak for them: only I am in a position to do so, and I swear they are all lucid, simple, empty, and one, without trace of division.

If this is true of my head, it is equally true of everything I take to be “myself” and “here” - in brief, of this total body-mind. What is it really like (I ask myself) where I am, now? Am I shut up in what Marcus Aurelius called this bag of blood and corruption (and what we might call this walking zoo, or cell-city, or chemical factory, or cloud of particles), or am I shut out of it? Do I spend my life embedded inside a solid, man-shaped block (roughly six feet by two by one), or outside that block, or perhaps both inside and outside it? The fact is: things aren't like that at all. There are no obstructions here, no inside or outside, no room or lack of room, no hiding place or shelter: I can find no home here to live in or to be locked out of, and not an inch of ground to build it on. But this homelessness suits me perfectly - a void needs no housing. In short, this physical order of things, so solid-looking in appearance and at a distance, is always soluble without residue on really close inspection.

And I find this is true, not only of my human body, but of my total Body, the universe itself. (Even from the outsider's viewpoint, the distinction between these embodiments is an artificial one: this little body is so united functionally to all other things, so dependent upon its environment, that it is non-existent and unthinkable by itself; in fact, no creature can survive for a moment except as that one Body which alone is all there, self-contained, independent, and therefore truly alive.) How much of this total Body I take on depends upon the occasion, but automatically I feel my way into as much as I need. Thus I may with perfect ease identify myself in turn with my head, my six-foot body, my family, my country, my planet and solar system (as when I imagine them threatened by others) - and so on, without ever coming up against any limit or barrier. And however great or small my temporary embodiment - this part of the world that I call mine and take to be here, that I am now thinking and feeling for, that I have for backing, whose point of view I have adopted, into whose shoes I put myself - it invariably turns out to be void, nothing here in itself. The reality behind all appearances is lucid, open, and altogether accessible. I know my way in and out of the secret inmost heart of every creature, however remote or repulsive it might seem to the outsider, because we all are one Body, and that Body is one Void.

And that Void is this void, complete and indivisible, not shared out or split up into mine and yours and theirs, but all of it present here and now. This very spot, this observation-post of mine, this particular “hole where a head should have been” - this is the Ground and Receptacle of all existence, the one Source of all that appears (when projected “over there”) as the physical or phenomenal world, the one infinitely fertile Womb from which all creatures are born and into which they all return. It is absolutely Nothing, yet all things; the only Reality, yet an absentee. It is my Self. There is nothing else whatever. I am everyone and no-one, and Alone.

In the months and years that followed my original experience of headlessness, then, I tried very hard to understand it, with the results that I have briefly described. The character of the vision itself didn't change during this period, though it tended to come more easily when invited, and to stay longer. But its working out, its meaning, developed as it went along, and was of course much influenced by my reading. Some help and encouragement I certainly found in books - scientific, philosophical, and religious. In particular, I found that some of the mystics seemed to have seen and valued what I see myself to be, here.

Discussion, on the other hand, proved almost invariably quite fruitless. “Naturally I can't see my head,” my friends would say. “So what?” And foolishly I would begin to reply: “So everything! So you and the whole world are turned upside down and inside out ...” It was no good. I was unable to describe my experience in a way that interested the hearers, or conveyed to them anything of its quality or significance. They really had no idea what I was talking about - for both sides an embarrassing situation. Here was something perfectly obvious, immensely significant, a revelation of pure and astonished delight - to me and nobody else! When people start seeing things others can't see, eyebrows are raised, doctors sent for. And here was I in much the same condition, except that mine was a case of not seeing things. Some loneliness and frustration were inevitable. This is how a real madman must feel (I thought) - cut off, unable to communicate.

An added reason for dismay was the fact that, among my acquaintances, it was often the more cultivated and intelligent who seemed specially unable to see the point: as if headlessness were an infantile aberration which, like thumb-sucking, one should have grown out of and forgotten long ago. As for writers, some of the most brilliant positively went out of their way to tell me I was crazy - or else they were. Chesterton, in The Napoleon of Notting Hill ends his ironic list of scientific wonders with the crowning absurdity: men without heads! And the great philosopher Descartes (justly reckoned great because he starts his revolutionary inquiry by asking what is clearly given) goes one better: he actually begins his list of certainties - of things which are “true because perceived by the senses” - with the astonishing announcement: “Firstly, I perceived that I had a head.” Even the man in the street, who should know better, says of something particularly obvious: “Why, it's as plain as the nose on your face!” With all the world of obvious things to choose from, he had to pick that!

I still preferred the evidence of my own senses to all hearsay. If this was madness, at least it wasn't second-hand madness. In any case, I never doubted that what I saw was what the mystics saw. Only the odd thing was that so few seemed to have seen it quite this way. Most of the masters of the spiritual life appeared to have “kept their heads”; or if not, few thought the loss worth mentioning. And certainly none of them, so far as I could discover, included the practice of headlessness in any curriculum of spiritual exercises. Why was such an obvious pointer, such a convincing and ever-present demonstration of that Nothingness which spiritual leaders never tire of proclaiming, so neglected? After all, it's absurdly obvious; there's no escaping it. If anything hits you in the face, this does. I was puzzled: even, at times, discouraged.

And then - better late than never - I stumbled upon Zen.

* * * *

Zen Buddhism has the reputation of being difficult - and almost impossibly so for Westerners, who for this reason are often advised to stick to their own religious tradition if they can. My own experience has been exactly the other way round. At last, after more than a decade of largely fruitless searching everywhere else, I found in the words of the Zen masters many echoes of the central experience of my life: they talked my language, spoke to my condition. Many of these masters, I found, had not only lost their heads (as we all have) but were vividly aware of their condition and its immense significance, and used every device to bring their disciples to the same realization. Let me give a few examples.

The famous Heart Sutra, which summarizes the essence of Mahayana Buddhism and is daily recited in Zen monasteries, having begun by stating that the body is just emptiness, declares that there is no eye, no ear, no nose. Understandably, this bald pronouncement perplexed the young Tung-shan (807-869); and his teacher, who was not a Zenist, also failed to make much of it. The pupil surveyed the teacher carefully, then explored his own face with his fingers. “You have a pair of eyes,” he protested, “and a pair of ears, and the rest; and so have I. Why does the Buddha tell us there are no such things?” His teacher replied: “I can't help you. You must be trained by a Zen master.” He went off and took this advice. However, his question remained unanswered till, years later, he happened while out walking to look down into a pool of still water. There he discovered those human features the Buddha was talking about - on show where they belonged, where he had always kept them: over there at a distance, leaving this place forever transparent, forever clean of them, as of everything else. This simplest of discoveries - this revelation of the perfectly obvious - turned out to be the essential realization that Tung-shan had been seeking for so long, and it led to his becoming not just a noted Zen master himself, but the founder of Soto, which is today Zen's largest sect.

A century or more before this incident, Hui-neng (637-712), the Sixth Patriarch of Zen, had given his famous piece of advice on the same subject. He counselled his brother-monk Ming to call a halt to all his craving and cogitation, and see . “See what at this very moment your own face looks like - the Face you had before you (and indeed your parents) were born.” It is recorded that Ming thereupon discovered within himself that fundamental source of all things which hitherto he had sought outside. Now he understood the whole matter, and found himself bathed in tears and sweat. Saluting the Patriarch, he asked what other secrets remained to uncover. “In what I have shown you,” replied Hui-neng, “there is nothing hidden. If you look within and recognize your own ‘Original Face', all secrets are in you.”

Hui-neng's Original Face (No-face, No-thing at all) is the best known and for many the most helpful of all Zen koan-anecdotes: over the centuries in China it is said to have proved an uniquely effective pointer to enlightenment. In fact, according to Daito Kokushi (1281-1337), all the seventeen hundred koans of Zen are simply pointers to our Original and Featureless Face. Of it, Mumon (13th c.) says:

You cannot describe it or draw it,

You cannot praise it enough or perceive it.

No place can be found in which to put the Original Face;

It will not disappear even when the universe is destroyed.One of Hui-neng's successors, the Zen master Shih-t'ou (700-790), took a slightly different line. “Do away with your throat and lips, and let me hear what you can say,” he commanded. A monk replied: “I have no such things!” “Then you may enter the gate,” was the encouraging reply. And there's a very similar story of a contemporary of Shih-t'ou's, master Pai Chang (720-814), who asked one of his monks how he managed to speak without throat, lips or tongue. It is, of course, from the silent Void that one's voice issues - from the Void of which Huang-Po (d. 850) writes: “It is all-pervading, spotless beauty; it is the self-existent and uncreated Absolute. Then how can it even be a matter for discussion that the real Buddha has no mouth and preaches no Dharma, or that real hearing requires no ears, for who could hear it? Ah, it is a jewel beyond all price.”

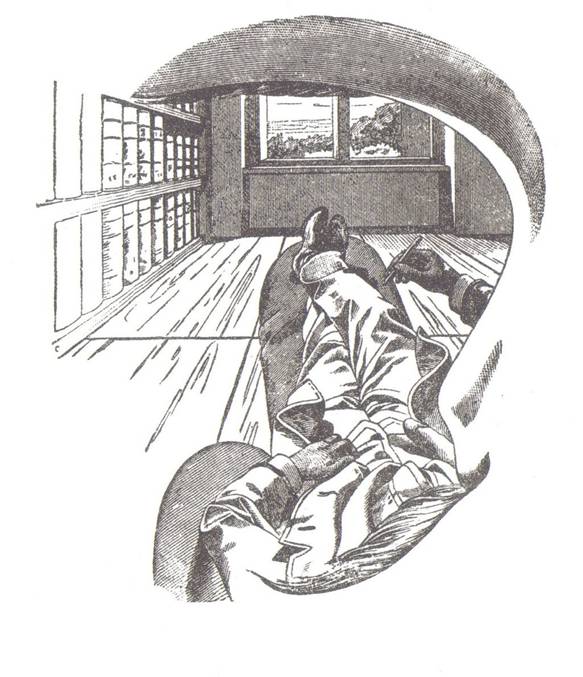

As an aid to such a realization, Bodhidharma, the First Patriarch of Zen (6th c.) is said to have prescribed a good hammerblow on the back of the head. Tai-hui (1089-1163) was equally uncompromising: “This matter (Zen) is like a great mass of fire: when you approach it your face is sure to be scorched. It is again like a sword about to be drawn; when it is once out of the scabbard, someone is sure to lose his life ... The precious vajra sword is right here and its purpose is to cut off the head.” Indeed this beheading was a common topic of conversation between Zen master and pupil. For instance, this 9th century exchange:

Lung-ya: If I threatened to cut off your head with the sharpest sword in the world, what would you do?

The master pulled in his head.

Lung-ya: Your head is off!

The master smiled.Evidently master and pupil, both headless, understood each other well. How well, also, they would have understood the advice of the Muslim Jalalu'l-Din Rumi, Persia's foremost mystical poet (1207-1273): “Behead yourself!” “Dissolve your whole body into Vision: become seeing, seeing, seeing!”

“I have learned from Him,” says another great mystical poet, the Indian Kabir (b. 1440), “to see without eyes, to hear without ears, to drink without mouth.”

However could Kabir see, if he had no eyes to see with? Well, as we have already noted, modern science itself agrees that we don't really see with our eyes. They are merely links in a long chain stretching from the sun, through sunlight and atmosphere and illuminated objects, through eye lenses and retinae and optic nerves, right down to particle/wavicle-haunted space in a region of the brain, where at last (it's said) seeing really occurs. In fact, the deeper the physiologist probes into the object, the nearer he gets to the Emptiness which is the Subject's direct experience of himself - the Emptiness which is the only Seer and Hearer, the sole Experiencer. (Not that he can ever, no matter how refined his instruments and techniques, get to the Subject by probing into the object: to do that he has simply to turn his attention round 180°.) And this lines up perfectly with what the old Zen masters say. “The body,” Rinzai (d. 876) tells us, “does not know how to discourse or to listen to a discourse ... This which is unmistakably perceivable right where you are, absolutely identifiable yet without form - this is what listens to the discourse.” Here the Chinese master, along with Kabir and the rest, is echoing the Surangama Sutra (a pre-Zen Indian scripture) which teaches that it's absurd to suppose that we see with our eyes, or hear with our ears: it's because these have melted together, and vanished into the absolute Emptiness of our “original bright and charming Face,” that experience of any sort is possible.

Still earlier, the Taoist sage Chuang-tzu (c. 300 B.C.) draws a delightful picture of this featureless Face or empty head of mine. He calls it “Chaos, the Sovereign of the Centre,” and contrasts its utter blankness here with those familiar seven-holed heads out there: “Fuss, the god of Southern Ocean, and Fret, the god of the Northern Ocean, happened once to meet in the realm of Chaos, the god of the Centre. Chaos treated them very handsomely and they discussed together what they could do to repay his kindness. They had noticed that, whereas everyone else has seven apertures, for sight, hearing, eating, breathing, Chaos had none. So they decided to make the experiment of boring holes in him. Every day they bored a hole, and on the seventh day Chaos died.”

No matter how much I fuss and fret, and renew my attempts to murder the Sovereign of the Centre by superimposing my human seven-holed features upon him, I can never succeed. The mask out there in the mirror can never touch my Original Face here, much less disfigure It. No shadow can fall upon Chaos, the unbodied and eternal King.

* * * *

But why all this emphasis on the disappearance of the face and head, rather than of the body as a whole? The answer is plain for humans to see. (Crocodiles and crabs would have a different story to tell!) For me here the face with its sense organs happens to be quite special in that it's always absent, always absorbed in this immense Void which I am; whereas my trunk and arms and legs are sometimes similarly absorbed and sometimes not. How much the Void currently includes, and excludes, is unimportant: for I see that it remains infinitely empty and infinitely big regardless of the scope or importance of the finite objects it's taking care of. It makes no real difference whether it's dissolving my head (as when I look down), or my human body (as when I look out), or my Earth-body (as when, out-of-doors, I look up), or my Universe body (as when I close my eyes). Everything there, no matter how tiny or vast, is equally soluble here, equally capable of coming and showing me that I am no-thing here.

In the literature we find many eloquent accounts of the dissolution of the whole body. I quote a few examples.

Yengo (1566-1642) writes of Zen: “It is presented right to your face, and at this moment the whole thing is handed over to you ... Look into your whole being ... Let your body and mind be turned into an inanimate object of nature like a stone or a piece of wood; when a state of perfect motionlessness and unawareness is obtained all the signs of life will depart and also every trace of limitation will vanish. Not a single idea will disturb your consciousness, when lo! all of a sudden you will come to realize a light abounding in full gladness. It is like coming across a light in thick darkness; it is like receiving treasure in poverty. The four elements and the five aggregates (your entire bodily make-up) are no more felt as burdens; so light, so easy, so free you are. Your very existence has been delivered from all limitations; you have become open, light, and transparent. You gain an illuminating insight into the very nature of things, which now appear to you as so many fairy-like flowers having no graspable reality. Here is manifested the unsophisticated self which is the Original Face of your being; here is shown all bare the most beautiful landscape of your birthplace. There is but one straight passage open and unobstructed through and through. This is where you surrender all - your body, your life, and all that belongs to your inmost self. This is where you gain peace, ease, non-doing, and inexpressible delight.”

The characteristic lightness which Yengo refers to was experienced by the Taoist Lieh-tzu (c.400 B.C.) to such a degree that he seemed to be riding on the wind. This is how he describes the feeling: “Internal and external were blended into a unity. After that, there was no distinction between eye and ear, ear and nose, nose and mouth: all were the same. My mind was frozen, my body in dissolution, my flesh and bones all melted together. I was wholly unconscious of what my body was resting on, or what was under my feet. I was borne this way and that on the wind, like dry chaff or leaves falling from a tree. In fact, I knew not whether the wind was riding on me or I on the wind.”

The 16th-century Zen master Han-shan says of the enlightened man that his body and heart are entirely non-existent: they are the same as the absolute Void. Of his own experience he writes: “I took a walk. Suddenly I stood still, filled with the realization that I had no body or mind. All I could see was one great illuminating Whole - omnipresent, perfect, lucid, and serene. It was like an all-embracing mirror from which the mountains and rivers of the earth were projected ... I felt clear and transparent.” “Mind and body dropped off!' exclaims Dogen (1200-1253) in an ecstasy of release. “Dropped off! Dropped off! This state must be experienced by you all; it is like piling fruit into a basket without a bottom, it is like pouring water into a bowl with a hole in it.” “All of a sudden you find your mind and body wiped out of existence,” says Hakuin (1685-1768): “This is what is known as letting go your hold. As you regain your breath it is like drinking water and knowing it is cold. It is joy inexpressible.”

In our own century, D.T. Suzuki sums up the matter: “To Zen, incarnation is excarnation; the flesh is no-flesh; here-now equals emptiness (sunyata) and infinity.” Outside Zen, it's not easy to find statements quite so clear, and so free from religiosity, as this. However, many parallels can be found in other traditions, as soon as one knows what to look for. This is only to be expected: the essential vision must transcend the accidents of history and geography.

Inevitably the closest parallel is to be found in India, the original home of Buddhism. Sankara (c.820), the great sage and interpreter of Advaita or absolute nonduality, taught that a man has no hope of liberation until he ceases to identify himself with the body, which is a mere illusion born of ignorance: his real Self is like space, unattached, pure, infinite. Confusing the unreal body with this real Self is bondage and misery. This doctrine still survives in India. One of its most lucid recent exemplars, Ramana Maharshi (1879-1950), would say to inquirers: “Till now you seriously considered yourself to be the body and to have a form. That is the primal ignorance which is the root cause of all trouble.”

Nor is Christianity (though, as Archbishop Temple observed, it is the most materialistic of the great religions) unaware of the fact that genuine illumination must dispel the dark opacity of our bodies no less than of our souls. “When thine eye is single,” said Jesus mysteriously, “thy whole body also is full of light.” This single eye is surely identical with the precious Third Eye of Indian mysticism, which enables the seer simultaneously to look in at his Emptiness and out at what's filling it. And the same, also, as the priceless gem which (according to Eastern tradition) we search everywhere for but here on our foreheads, where we all wear it.

Augustine Baker (1575-1641) writes of the Christian contemplative: “At length he cometh to a pure and total abstraction; and then he seemeth to himself to be all spirit and as if he had no body ... The purer and perfecter such abstraction is, the higher is the man ascended to perfection.” This is a comment upon a well-known passage in The Cloud of Unknowing, a 14th century mystical work which teaches that a vivid awareness of our non-existence is the prerequisite of pure joy: for “all men have matter for sorrow: but most specially he feeleth matter of sorrow that knoweth and feeleth that he is.” But of course this indispensable self-naughting is a favourite theme of all Christian mysticism. No one describes its two sides more boldly than St. Bernard (1091-1153): “It is no merely human joy to lose oneself like this, so to be emptied of oneself as though one almost ceased to be at all; it is the bliss of heaven ... How otherwise could God be ‘all in all', if anything of man remained in man?”

Sometimes in the West, even the mystic's language is as Zen-like as what it describes. Gerlac Peterson (1378-1411), speaks of a “showing” that is “so vehement and so strong that the whole of the interior man, not only of his heart but of his body, is marvellously moved and shaken … His interior aspect is made clear without any cloud.” His spiritual eye is wide open. Instead of remaining, as Shakespeare puts it,

Most ignorant of what he's most assured,

His glassy essence,and therefore behaving like an angry ape - he sees into its utmost depths, into the transparent heart of Reality.

With our attention fastened upon the physical world, we fail to see through it. Disregarding our inside information, we look on our little human bodies as opaque and divided from our total Body, the Universe, which as a result seems equally opaque and divided. Some of our poets, however, are not so tricked and taken in by (so-called) common-sense, but instead take in all things and revel in their transparency. Rainer Maria Rilke wrote of his dead friend:

For these, these shadowy vales and waving grasses

And streams of running water were his face,but didn't stop with dissolving the human face and human body: his declared mission was to go on and “render the earth we live on, and by extension the universe, invisible, and thus to transform it into a higher plane of reality.” For Rilke, this ever-present Void, our undying Face, has no boundaries. As Traherne says of himself:

The sense itself was I.

I felt no dross nor matter in my soul,

No brims, no borders, such as in a bowl

We see. My essence was capacity.And, in a better-known passage: “You never enjoy the world aright, till the sea itself floweth in your veins, till you are clothed with the heavens, and crowned with the stars.”

This is none other than the Zen experience of satori - only the language differs a little. At the moment of satori there is an explosion, and a man has no body but the universe. “He feels his body and mind, the earth and the heavens, fuse into one pellucid whole - pure, alert, and wide-awake,” says master Po Shan:

The whole earth is but one of my eyes,

But a spark of my illuminating light.In numerous texts we are told how the enlightened man as if by magic engulfs rivers, mountains, seas, the great world itself, reducing them all to the Void here, to nothing at all; and then, out of this Void, creates rivers, mountains, seas, the great world itself. Without the slightest discomfort, he swallows all the water in the West River, and spews it up again. He takes in and abolishes all things, produces all things. He sees the universe as nothing else than the outflowing of his own profound Nature, which in itself remains unstained, absolutely transparent. Now he is restored to himself as he really is: as the very heart of existence, from which all being is made manifest. In brief, he is deified. Established at the unique Source, he cries: “I am the Centre, I am the Universe, I am the Creator!” (D.T. Suzuki) Or: “I am the cause of mine own self and all things!” (Eckhart) In the vivid language of Zen, the mangy cur has become the golden-haired lion roaring in the desert, spontaneous, free, energetic, magnificently self-sufficient, and alone. Arrived Home at last, he finds no room for two. Our own Traherne once more echoes Eastern masters when he exclaims: “The streets were mine, the temple was mine, the people were mine, their clothes and gold and silver were mine, as much as their sparkling eyes, fair skins and ruddy faces. The skies were mine, and so were the sun and moon and stars, and all the World was mine: and I the only spectator and enjoyer of it.”

POSTSCRIPT

Let's assume that you would like to continue along this Way. In that case, you may be asking such questions as: Where do I go from here? To whom do I look for further guidance and encouragement? What supporting group could I join? For a spiritual movement that's as alive and as distinctive as most others, the Headless Way is remarkably lacking in organization. It resembles the people who take it up in that it, too, is without a head - in the sense that it has no presiding authority, no governing council or headquarters, and no staff looking after a duly card-indexed and paid-up membership who meet regularly and try to follow certain guidelines.

The reason for this absence of structure doesn't lie in any lukewarmness, or reluctance to disseminate the experience this book is about. Rather the reverse. It arises from the nature of that experience itself - as the ultimate in Self-reliance. Or, in more detail, from the fourfold realization that the way really to live is to look in and see Who is doing so, that only you are in a position to see this “Who”, that this in-seeing establishes You as the authority on what matters supremely, and that accordingly your path will not conform to some set pattern laid down from above, by this or any other book or person or system. For example, though none of the eight stages described here can be bypassed, you may well find yourself negotiating the later ones in a different order, and certainly in a manner that's very much your own.

Looked at from outside, as a grouping of self-styled headless characters doing their thing, their apparent anarchy is at once a huge disadvantage (inasmuch as organization is necessary to get things off the ground) and something of an advan- tage (inasmuch as organizations spawn problems that obscure - if not undermine - those very things they were formed to advance). Looked at from inside, however, this worldly wisdom ceases to apply: our concern here isn't with things but with the No-thing they come from, with the Indefinable that reduces to nonsense all plans to put it on the map and make something of it. Why set up a Group or Faction - which at once splits humanity into us enlightened insiders and those endark- ened outsiders - a Faction (if you please!) whose stated aim is to show there's no such split, that intrinsically they are us, and that we are all perfectly enlightened already? The truth is that the Headless Way isn't a way after all, a means of getting somewhere. Everything one's heart could possibly desire is freely given from the very start. This makes it strikingly different from those disciplines and courses which come in progressive installments, with the real goods to be delivered some day: and meanwhile there has to be this Institution to lay down the rules and administer the whole business. Who, anyway, would join a set-up and pay good money to be given - when sufficiently trained - what he sees he already has, in full measure, pressed down and shaken together and running over?

Our overriding purpose, then - which is seeing into and living from Nothingness - is necessarily organization-resistant. For all other purposes we remain free to join whatever organization we please. This means that, having no “church” of our own, we offer minimal challenge to others, and hopefully remain more able to learn from them and contribute to them. And in fact a number of our “headless” friends find it helpful to belong to some established religious or quasi-religious community. But the headless one remains the Only One, and sees itself as the Alone, and faces its Solitariness. At this level there are no others.

All the same - and descending now to the level where others do exist - the difficulty of keeping up this seeing by oneself, of going it alone, can scarcely be exaggerated. For the majority of us caught up in this most daring and exacting of adventures, the company of fellow adventurers is indispensable. Accordingly it would be unrealistic - worse: irresponsible and uncaring - if we were to encourage people to take the message of this book to heart, yet fail to follow it up with all the continued support that the nature of the enterprise allows. And, in fact, we do have much to offer readers who are committed to going on:

First and foremost, there are loving friends, a network - loose, scattered, alto- gether informal - of seers who use every available means of keeping in touch. Second, some assistance in that aim is offered by the website www.headless.org. Third, besides the large and precious (and increasingly available) mystical literature of the world - mystical in the sense that it points to our true Identity - there is a small number of books and other aids by the author. Fourth and last, if headless friends still prove hard to find, they may not be so hard to make. The condition, in spite of all resistances, is infectious and uniquely communicable. Anyhow, one of the best ways to keep it up is to pass it on.

But in the end all such considerations and contrivances are quite marginal. For it's not as humans - as so many separate individuals helping one another to see Who they really are - that we come to that vision, but (in the Upanishadic phrase) as “the One Seer in all beings”. Self-seeing is indeed the prerogative and specialty of the One, and in the last resort all our efforts - organized or chaotic - to help that seeing along are quite hilarious.

To repeat our initial question, then: where do we go now? The answer is: nowhere. Let us resolutely stay right here, seeing and being This which is Obviousness itself, and take the consequences. They will be all right.

PDF: Zen Experience: A Western Approach

by Douglas Harding

The Shollond Trust (2023)

On the front cover the seal image depicting the character 道 (Tao/Dao in Chinese) in the Shuowen seal script.

Douglas E. Harding: A világ vallásai

(Religions of the World)

Filosz Kiadó, Budapest, 2008.

Douglas E. Harding (1909. febr. 12. – 2007. jan.11.)

angol misztikus, filozófus, spirituális tanítóDouglas E. Harding ról sok mindent el lehet mondani, csak azt nem, hogy szűk látókörű specialista volt. Az 1930-as években építészként Indiába költözött családjával, és itt érte a II. világháború kirobbanása.

Korábban is komolyan érdeklődött a világgal és az emberrel kapcsolatos filozófiai kérdések iránt, de a háború veszélyeivel szembesülve sürgetően érezni kezdte: meg kell találnia valódi önazonosságát, mielőtt meghal. Életének meghatározó spirituális élménye a Himalájában érte.Immár klasszikusnak számító művében, az On Having No Head -ben leírja tapasztalását: a „fejnélküliséget”, az éntelenség misztikus érzését. Később számos könyvet írt, és különböző tudatossági technikákat fejlesztett ki, melyek segítségével igyekezett megosztani az érdeklődőkkel a „fejnélküliség” élményét és annak mindennapi életre gyakorolt hatásait. Emellett összehasonlító vallástudományt tanított a cambridge-i egyetemen. Douglas E. Harding 2007-ben halt meg, nem sokkal kilencvennyolcadik születésnapja előtt.

Douglas E. Harding e könyvében nem annyira a vallás népszerű formáival foglalkozik, mint inkább megpróbál azoknak a magasabb rendű vagy alapvetőbb belátásoknak a mélyére hatolni, melyekből a népszerűbb formák erednek. A világ vallásai olvasása során nemcsak más kultúrákat és világnézeteket ismerhetünk meg, de arra is lehetőségünk nyílik, hogy önmagunkba tekintsünk.

„Jelen írásommal az a célom, hogy bemutassam: a világ minden nagy vallása szükséges szerve a Val lásnak mint egésznek, mint élő szervezetnek, mely egy és osztha tatlan. Ébredjünk csak tudatára ennek a ténynek, és máris baráti légkört teremtünk, végtére is az az egyetlen módja a nagy vallások keltette, látszólag disszonáns hangok összhangba hozásának, hogy fi gyelmesen meghallgatjuk, mit mondanak valójában. Bátran kijelenthetem, hogy ha így teszünk, mennyei muzsikát fogunk hallani.” (Részlet a könyvből)

D.E. Harding elemzése a zen koanokról

Min meditál a tanítvány? Ez attól függ, melyik zen iskolához tartozik (mert számos van), és a spirituális fejlődés milyen fokán áll. Az apát talán adott neki egy koant, hogy oldja meg.

A zen koan

A Zen koan egy fajta paradox fejtörő, melynek teljes megoldása egyenértékű a megvilágosodással. A koan őrültsége elengedhetetlen. Nem olyan, mint egy intellektuális kérdés, mint például az, hogy „Mi az élet értelme?” Éppen ellenkezőleg, a célja az, hogy összezavarja az értelmet, megállásra bírja a nyughatatlan elmét, hogy eljusson annak tudattalan forrásáig. Ez az első oka annak, miért őrült egy zen koan: az a rendeltetése, hogy aláaknázza a gondolkodást. A második ok az, hogy a végső kétségbeesésbe kell kergetnie a tanítványt. A mester újra meg újra visszaküldi a tanítványt –időnként ütésekkel, máskor a haragjával kísérve –a meditációs párnájához, azzal a lesújtó megjegyzéssel, hogy semmivel sem került közelebb kóanja megoldásához. Ez a könyörtelen bánásmód hónapokig, sőt évekig eltarthat. A tanítvány talán soha nem is éri el a szatorit vagy megvilágosodást –ebben az életében. De kitart.

A harmadik oka annak, hogy miért őrült egy koan, az, hogy nem is az: a tanítvány az őrült! Hadd próbáljam meg érzékeltetni ezt. Az egyik legismertebb koan –mindegyik koan kulcsa –az igazi vagy eredeti arcunk rejtvénye. A 14. századi mester, Daitó Kokusi szerint: „Az ezerhétszáz zen koannak, amelynek a zen tanítványok szentelik magukat, csak egy a célja: hogy meglássák Eredeti Arcukat.” Ha ezt a koant modern nyelven akarnánk megfogalmazni, valahogy így hangzana: „Ne akarj semmit, hagyd abba a gondolkodást, lazítsd el magad, felejts el mindent, amiről azt képzeled, hogy tudod magadról (azt is, amit a tükörben látsz), nézz ide, arra a helyre, ahol vagy, és lásd meg, milyen most az arcod –mely az Arcod volt, mielőtt megszülettél!” Figyeljük meg, hogy a tanítványnak meg kell látnia – nem elég, ha megérti –, hogy Valódi Arca csak egy másik neve a mahájána buddhizmus és a taoizmus ürességének és a hinduizmus Átman-Brahmanjának. Látnia kell valódi, nem emberi Arcát, és tisztábban kell látnia, mint ahogy azt a másik, emberi arcot látja egy méterre a tükörben – azt az emberi arcot, amely sohasem volt az övé.

Ne lepődjünk meg, ha ez még nem jelent nekünk semmit. A tanítványnak sem jelent. Vagy másként megfogalmazva: túl sokat jelent, pedig a lényeg nem a jelentés, hanem a látás. Ám egy szép napon a tanítvány eljut oda, hogy erőforrásai kimerülnek. Ekkor feladja, nem tud tovább gondolkodni, és teljes kétségbeesésében csak néz –s egy szempillantás alatt meglátja Valódi Arcát, és megvilágosodik. Az örömtől verejtékezve, remegve, sírva és nevetve rohan a mesterhez. És a mester, immár a keménység és a harag minden nyoma nélkül, gyengéden megsimogatja térdelő tanítványa fejét. A magyarázkodás szükségtelen –és különben is lehetetlen.

–Végre –mondja a mester –, végre látod!

–Hogyhogy nem vettem észre eddig, pedig olyan nyilvánvaló! –súgja a tanítvány.

–Túl nyilvánvaló –feleli a mester –, nehéz észrevenni. Az emberek ki nem állhatják az egyszerűséget. Azt szeretik, ha a dolgok nehezek és bonyolultak. Az a baj, hogy túl könnyű!

Megvilágosodás

A zen tanítvány megvilágosodása rendszerint kemény gyakorlással töltött hosszú időszak végén jön el. De vannak olyan példák, amikor nagyon gyorsan és könnyen érkezett. Erre az a buddhista magyarázat, hogy a szükséges erőfeszítést már a korábbi életeiben megtette az ember, és most annak szüreteli le a gyümölcseit. Mindenesetre senki sem tudhatja előre, mennyi időre lesz szükség a megvilágosodáshoz az ő esetében: az is lehet, hogy a következő öt perc elhozza, de megtörténhet, hogy ötvenévnyi spirituális fáradozás szükséges hozzá. Tegyük fel, hogy a tanítvány felfogta a koant, és meg merte tenni, amit az javasolt: kereste és meglátta Valódi vagy Eredeti Arcát abban a pillanatban. Miért ne lenne ekkor ugyanolyan megvilágosodott, mint az a tanítvány, akinek mindez fél évszázadba tellett? Mindehhez gyakorlatilag semmi köze a korának, vallásának (vagy éppen vallástalanságának), erkölcsének, tanultságának, nemének, de még az értelmének sem! A „magyarázat” a buddhizmus szerint a jó karmájában rejlik, azokban az érdemekben, melyeket a hosszú-hosszú életek során összegyűjtött. A keresztények tiszta kegyelemnek vagy isteni adománynak hívnák inkább, míg egy nem vallásos értelmező a puszta szerencsének. Mindenesetre arra a kérdésre, hogy „Én is megláthatom-e az Eredeti Arcomat?”, csak egyetlen válasz van: „Próbáld ki, és nézd meg!”

Mindazonáltal a zen szótó iskolája (amely napjainkban a legnagyobb a zen tradíciók közül Japánban) elutasítja a kóan módszerét és bármilyen megvilágosodáshoz vezető eszközt, hiszen úgy tartja, hogy a megvilágosodás már amúgy is igaz természetünk. A tanítványt arra buzdítja, hogy már a kezdetektől élvezze ezt a természetet (amely „nem természet”). Erről szól a zazen vagy ülő meditáció: gyakorolni és megszilárdítani az ember jelenvaló megvilágosodását, és nem próbálni elérni azt a jövőben. Most vagy soha!

A zenben –akárcsak a többi fontos spirituális hagyományban –mindig is voltak olyan mesterek, akik azt tanították, hogy a megvilágosodás (szatori, megszabadulás, felébredés, önmegvalósítás, üdvözülés) nemhogy nem a világ legnehezebb dolga, hanem éppen a legkönnyebb és legtermészetesebb. E kérdés eldöntésének az egyetlen módja az, ha kipróbáljuk. „A zen a megvilágosodást helyezi az első helyre –mondja Ummon japán zen mester –, a rossz karmádtól majd szabadulj meg azután.” Ummon nem engedi meg, hogy kihúzzuk magunkat az emberi gyengeségeinkkel való szembenézés alól, s hogy ne vegyük azokat tudomásul minden szinten. Ezt a hosszas és emberpróbáló munkát nem kerülhetjük el. Gyakorlatilag azt tanácsolja, hogy kezdjük azzal, ami már adott és azonnal elérhető, bármi legyen is a problémánk, vagyis azzal, ami már tökéletes –nevezetesen a forrásunkkal vagy középpontunkkal. Ezután, tudatosan megállapodva a középpontban, már olyan helyzetben leszünk, hogy megbirkózhatunk az összes külső rendetlenséggel.

Szúfizmus, az iszlám misztikája

A szúfizmus témája szintén az Istennek való önátadás. Nem kelletlen fegyverletétel, nem pusztán az, hogy engedjük, hogy legázoljon bennünket a végzetnek nevezett könyörtelen gépezet, hanem a szerelmes örömteli önátadása Kedvesének, a lenyűgözöttség, a belemerülés olyan elragadtatott boldogsága, amelyben az ember nyomtalanul eltűnik. A 12. századtól kezdve a nagy szúfik számára (mint ugyanennek a kornak számos keresztény misztikusa számára) ez a hasonlóság –ez a megdöbbentő párhuzam az emberi szeretet és az Istenben való elmerülés között –több egyszerű hasonlatnál. Át- meg átszövi az egész szúfi spirituális életet, és –különösen Rúmival, a legnagyobb perzsa misztikussal

Dzsaláladdín Rúmi a Perzsa Birodalom Balh nevű eldugott kis falujában született (mely ma Afganisztánhoz tartozik), és élete legnagyobb részét a törökországi Konjában töltötte. (A ford.) –a világ legpompásabb misztikus költészetét hozta létre. A szúfizmus nyelvezete érzéki, dús fantáziájú, annyira burkolt és kétértelmű, amennyire a költészetnek lennie kell, és szinte túlcsordul a hevesen lángoló érzelmektől. Kirívó a különbség a buddhista spiritualitás nyersen őszinte és tárgyilagos kifejezésmódja és a szúfizmus hangvétele között. Ez utóbbinak megvan az összetéveszthetetlen vibrálása és féktelensége, mámora (ez a szúfik egyik kedvenc szava) és jellegzetes öröme.

Hogy a szúfizmus mennyit köszönhet a többi nagy vallás misztikusainak, azt nehéz megállapítani. Alapjában véve ugyanazt mondja, mint azok, ám a maga módján, a saját zamatát hozzáadva. Csak néhány példa:„Elveszítém önmagam, hogy önmagam nem látom én…”

„Bizony, magasztos, drága kincs az élet…”

„…egy tiszta tárgy, amely az óceánba süllyed, elveszíti saját egzisztenciáját, és részesül az óceánban annak mozgásából. Mivel megszűnik elkülönült tárgyként létezni, megtartja szépségét. Ő létezik és nem létezik. Hogy lehet ez? A szellem számára ez elképzelhetetlen.”

„Aki azért hagyja el ezt a világot, hogy ezt az utat kövesse, halálát leli; és aki halálát leli, az megleli a halhatatlanságot.”„A bölcs éjjeli lepke, aki a távolból figyelte őt, látta, hogy a láng és a lepke egynek látszik, és így szólt: »Megtudta, amit tudni akart; de csak ő érti ezt a titkot. Többet nem lehet mondani.«”

„Ó, te, ki létezel és mégsem vagy, kinek boldogsága a boldogtalansággal keveredett… Légy bátor, égesd el értelmedet, és add át magad az ostobaságnak! Ha használni akarod ezt az alkímiát, gondolkozz egy kicsit, kövesd a példámat, és mondj le magadról! Vonulj vissza csapongó gondolataidból a lelkedbe, hogy ezáltal elérd a spirituális szegénységet.”

„Ameddig azonosultok e világ dolgaival, nem fogtok rálépni az ösvényre.”

„Tudjátok, mitek van? Vonuljatok vissza bensőtökbe, és gondolkodjatok el ezen! Amíg nem ismeritek fel semmiségeteket, és amíg nem mondtok le büszkeségetekről, hiúságotokról és önszeretetekről, soha nem éritek el a halhatatlanság magasságait.”Attár (12. századi perzsa misztikus költő)

„Az életedbe fog kerülni ez az út. Ha jól csinálod.”

„Testem egy szál köpeny, szúfi szívem körül,

Kolostor a világ, mester a szeretőm.”

„Minden világban egy-egy pupillát látok.

Minden pupillában egy világot látok.”Rúmí: Mint a felhő, mint a szél.

Százharminchat rubá'í.

Nagy Imola fordításai.„Születtem azon nap, mikor Név se volt,

Se kit Név jelezzen, az ős Lét se volt.”

„De végül tekintém tulajdon szivem,

S imé ott enyém lett, ki másé se volt.”

„Ti óvjátok, muzulmánok, a bensőtök, de én immár

Vele eggyé-ötvöződtem, mint szív vélem sosem tudna.

Szerelméből szült ő engem, végül szívem nekiadtam.”

Perzsa költők antológiája. Weöres Sándor fordításai.

„Nem tudom megkülönböztetni magam a Fénytől.”Rúmi (13. századi perzsa misztikus költő)

Szúfizmus, az iszlám betetőződése