ZEN IRODALOM ZEN LITERATURE

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

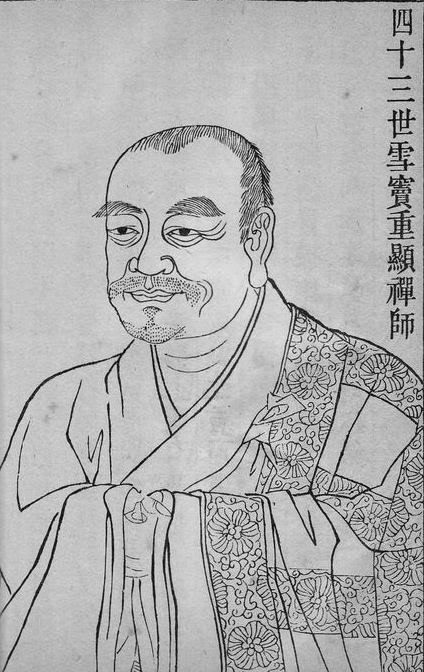

雪竇重顯 Xuedou Chongxian (980–1052), aka 明覺 Mingjue

(Rōmaji:) Setchō Jūken, aka Myōkaku

A whole independent genre of Chan literature evolved out of the practice of commenting on the gongan stories of past masters. Xuedou Chongxian compiled several collections of old gongan cases, attaching his own brief comments to each. These collections were called niangu (picking up the old [cases or masters]) when a prose commentary was attached and songgu (eulogizing the old [cases or masters]) when the commentary was in poetic form.

雪竇百則頌古集

Xuedou baize songgu

ji

(頌古百則 Songgu baize)

(Rōmaji:) Setchō Jūken: Setchō hyakusoku juko

shū

(Juko hyakusoku)

(English:) Odes to a Classic Hundred Standards / Verses on One Hundred Old Cases

(Magyar átírás:) Hszüe-tou Csung-hszien: Hszüe-tou paj-cö szung-ku (100 kóan)

(the original version is no longer extant and is only known through the content of the 碧巖録 Biyan lu)

雪竇百則拈古集

Xuedou baize niangu

ji

(拈古百則 Niangu baize)

(Rōmaji:) Setchō Jūken: Setchō hyakusoku nenko

shū

(Nenko hyakusoku)

(Magyar átírás:) Hszüe-tou Csung-hszien: Hszüe-tou paj-cö nien-ku (100 kóan)

(the original version of the 撃節録 Jijie lu)

瀑泉集 Puquan ji

(Rōmaji:) Bakusen shū

(English:) Cascade Collection

(Magyar:) Pu-csüan csi / Zuhatag gyűjtemény)

Tartalom |

Contents |

| 瀑泉集 Pu-csüan csi Zuhatag gyűjtemény |

雪竇顯和尚明覺大師頌古集 Xuedou xianheshang mingjue dashi songgu ji 雪竇和尚住洞庭語錄 Xuedou heshang zhu dongting yulu 瀑泉集 Puquan ji / Cascade Collection Xuedou houlu 雪竇後錄 (T 1996, 712c28-713a2) PDF: ”Poetry and Chan 'Gong'an': From Xuedou Chongxian (980—1052) to Wumen Huikai (1183—1260)” |

Works:

Dongting yulu 洞庭語錄,

Xuedou kaitang lu 雪竇開堂錄,

Puquan ji 瀑泉集,

Zuying ji 祖英集,

Songgu ji 頌古集,

Niangu ji 拈古集,

Xuedou houlu 雪竇後錄 (T 1996, 712c28-713a2)

The earliest extant Song version of Xuedou's records was printed in 1195, and can be found in the Sibu congkan xubian 四 部叢刊續編, vol. 29. They are given the title Xuedou siji 雪竇四集, which indicates that there are only four works of Xuedou in this collection.* The most popular version of Xuedou's discourse records is the Ming version, which includes six of Xuedou's works and now is included in the Taishō canon under the title Mingjue chanshi yulu 明覺禪師語錄. This collection does not include Xuedou's Verses on the Old Cases. The only complete collection of Xuedou's seven works is found in the Japanese Gosan 五山 version printed in 1289 and preserved in the Tōyō Bunko 東洋文庫 collection. The Gosan version has been republished in the series Zengaku tenseki sōkan 禅学典籍叢刊, vol. 2, under the title Secchō minkaku daishi goroku 雪竇明覚大師語録, which includes all seven of Xuedou's texts.

*The four texts are Xuedou xianheshang mingjue dashi songgu ji 雪竇顯和尚明覺大師頌古集 , Xuedou heshang niangu 雪竇顯和尚拈古 , Xuedou heshang mingjue dashi puquan ji 雪竇和尚 明覺大師瀑泉集 , Qingyuanfu xuedou mingjue dashi zuying ji 慶元府雪竇明覺大師祖英集 . The Sibu congkan xubian was printed by Shanghai hanfenlou 上海涵芬 樓 in 1932.

"The Yunmen line was greatly revived by the distinguished fourth generation master Xuedou Chongxian (d. 1052) and flourished over the succeeding generations, particularly through the school of Xuedou's successor

天衣義懷

Tianyi Yihuai (993-1064). It eventually died out when the last surviving master of the line did not find anyone he deemed capable of effectively receiving and transimitting the teaching. This event, which is recorded explicitly in Chan history, reflects the unwillingness of ancient Chan adepts in China to continue schools at the cost of reality, preferring to let a lineage die out rather than perpetuate empty forms. According to Japanese books, this tradition was not upheld so strictly in Japan, where there was far more proprietary interest in schools and sects, and even in China there are suggestions of faulty transmission in later times.

Xuedou was highly acclaimed as a poet, and many examples of his work are preserved in a number of texts. He is probably most famous for his collection of poetic comments on one hundred Chan stories enshrined in the classic Blue Cliff Record with prose commentaries by Yuanwu. Less well known in his collection of prose comments on one hundred Chan stories, called the Cascade Collection (瀑泉集), which was also expanded by Yuanwu's commentaries into the classic Measuring Tap (擊節錄). Xuedou's work has maintained a lasting influence through these books, particularly the Blue Cliff Record, which was for centuries a sort of standard Zen text in Japan. His Anthology on Outstanding Adepts (祖英集) was also lauded as a guide for the world by the founder of the southern branch of the Complete Reality school of Taoism, which had enormous influence in China during the Song, Jin, and Yuan dynasties." (Thomas Cleary)

HSUEH-TOU

Stories from his Cascade Collection [瀑泉集 Puquan ji]

Translated by Thomas Cleary

In: The five houses of Zen, 1997

In the fourth generation of Yunmen Zen House, another giant arose, the eminent Hsueh-tou, who was also a great writer and an outstanding poet. Traditionally regarded as the reviver of the House of Yun-men, Hsueh-tou is particularly famous as the author of the poetic commentaries on Zen stories of the classic collection Blue Cliff Record. Another collection of poetry is also attributed to Hsueh-tou, as well as an anthology of Zen stories with his own prose comments, the [瀑泉集 Puquan ji] Cascade Collection, selections of which are presented here to cap the section on Yunmen Zen.

Te-shan Guides the Crowd

TE-SHAN SAID to a group, “Tonight I won’t answer any questions. Anyone who asks a question gets a thrashing.”

At that point, a monk came forward and bowed, whereupon Te-shan hit him.

The monk said, “I haven’t even asked a question yet!”

Te-shan said, “Where are you from?”

The monk said, “Korea.”

Te-shan said, “You deserved a thrashing before you stepped on the boat!”

Fa-yen brought this up and said, “The great Te-shan’s talk is dualistic.”

Yuan-ming brought this up and said, “The great Te-shan has a dragon’s head but a snake’s tail.”

Hsueh-tou brought this up and commented, “Though the old masters Fa-yen and Yuan-ming skillfully trimmed the long and added to the short, gave up the heavy and went along with the light, this is not enough to see Te-shan.

“Why? Te-shan was as if holding the authority outside the door; he had a sword that would not invite disorder even when he didn’t cut off when he should.

“Do you want to see the Korean monk? He is just a blind fellow bumping into a pillar.”

Pai-chang and the Whisk

Pai-chang called on Ma-tsu a second time and stood there, attentive. Ma-tsu stared at the whisk on the edge of his seat.

Pai-chang asked, “Does one identify with this function or detach from this function?”

Ma-tsu said, “Later on, when you open your lips, what will you use to help people?”

Pai-chang picked up the whisk and held it up.

Ma-tsu said, “Do you identify with this function or detach from this function?”

Pai-chang hung the whisk back in its place.

Ma-tsu then shouted, so loudly that Pai-chang was deaf for three days.

Hsueh-tou brought this up and said, “Extraordinary, O Zen worthies! Nowadays, those who branch off in streams are very many, while those who search out the source are extremely few. Everyone says that Pai-chang was greatly enlightened at the shout, but is it really true or not?

“Similar ideographs resemble each other and get mixed up, but clear-eyed people couldn’t be fooled one bit. When Ma-tsu said, ‘Later on, when you open your lips, what will you use to help people?’ Pai-chang held up the whisk—do you consider this to be like insects chewing wood, accidentally making a pattern, or is it breaking out of and crashing into a shell at the same time?

“Do you want to understand the three days of deafness? Pure gold, highly refined, should not change in color.”

Hsueh-feng’s Ancient Stream

A monk asked Hsueh-feng, “How is it when the ancient stream is cold from the source?”

Hsueh-feng said, “When you look directly into it, you don’t see the bottom.”

The monk asked, “How about one who drinks of it?”

Hsueh-feng said, “It doesn’t go in by way of the mouth.”

The monk recounted this to Chao-chou. Chao-chou said, “It can’t go in by way of the nostrils.”

The monk then asked Chao-chou, “How is it when the ancient stream is cold from the source?”

Chao-chou said, “Painful.”

The monk said, “What about one who drinks of it?”

Chao-chou said, “He dies.”

Hsueh-feng heard this quoted and said, “Chao-chou is an ancient buddha; from now on, I won’t answer any more questions.”

Hsueh-tou brought this up and commented, “Everyone in the crowd says that Hsueh-feng didn’t go beyond this monk’s question, and that is why Chao-chou didn’t agree. If you understand literally in this way, you’ll deeply disappoint the ancients.

“I dissent. Only one who can cut nails and shear iron is a real Zen master. Going to the low, leveling the high, one could hardly be called an adept.”

Ts’ao-shu and the Nation of Han

Ts’ao-shu asked a monk, “Where have you recently come from?”

The monk said, “The nation of Han.”

Ts’ao-shu asked, “Does the emperor of Han respect Buddhism?”

The monk said, “How miserable! Lucky you asked me! Had you asked another, there would have been a disaster!”

Ts’ao-shu asked, “What are you doing?”

The monk said, “I don’t even see people’s existence—what Buddhism is there to respect?”

Ts’ao-shu asked, “How long have you been ordained?”

The monk said, “Twenty years.”

Ts’ao-shu said, “A fine ‘not seeing people’s existence’!” And he hit him.

Hsueh-tou commented, “This monk took a beating, but when he goes he won’t return. As for Ts’ao-shu, while he carried out the imperative, he roused waves where there was no wind.”

XUEDOU CHONGXIAN, “MINGJUE”

IN: Zen's Chinese heritage: the masters and their teachings

by Andy Ferguson

Boston: Wisdom Publications, 2000. pp. 364-367.

XUEDOU CHONGXIAN (980–1052) was a disciple of Zhimen Guangzuo. Xuedou came from Suining (near the modern city of Tongnan in Sichuan Province). Born into a prominent and wealthy family, the young man possessed extraordinary skills as a scholar. Determined to leave secular life and enter the Buddhist priesthood, he entered the Pu’an Monastery in Yizhou (near modern Chengdu City), where he studied the Buddhist scriptures under a teacher named Renxian.

Xuedou was recognized as an adept in both Buddhist and non-Buddhist disciplines. After receiving ordination he traveled to ancient Fuzhou (near the modern city of Tianmen in Hubei Province), where he studied under Zhimen Guangzuo. After five years Xuedou received Zhimen’s seal as an heir of the Yunmen lineage. Xuedou later lived at the Lingyin Temple in Hangzhou and Cuifeng Temple in Suzhou before finally taking up residence on Mt. Xuedou (near modern Ningbo City in Zhejiang Province).

Xuedou compiled the hundred kōans that are the core of the Blue Cliff Record, the well-known Zen text later annotated by Zen master Yuanwu Keqin.

Xuedou’s grand style of teaching rejuvenated the Yunmen lineage. The prominent Zen master Tianyi Yihuai was among his eighty-four disciples.

When he began studying with Zhimen, Xuedou put forth the question, “Before a single thought arises, can what is said be wrong?”

Zhimen summoned Xuedou to come forward. Xuedou did so. Zhimen suddenly struck Xuedou in the mouth with his whisk. Xuedou began to speak but Zhimen hit him again. Xuedou suddenly experienced enlightenment. He first assumed the abbacy at Cuiyan. He later moved to Xuedou.

Upon first entering the hall as abbot, but before ascending the seat, Xuedou looked out over the assembly and said, “If I’m to speak about coming face-to-face with the fundamental principle, then there’s no need to ascend the Dharma seat.”

He then used his hand to draw a picture in the air and said, “All of you follow this old mountain monk’s hand and see! Here are innumerable buddha lands appearing before you all at once. All of you look carefully. If you are on the river bank and still don’t know, don’t avoid moving mud and carrying water.” He then ascended the seat.

The head monk struck the gavel. A monk came forward to speak. Xuedou told him to stop and go back, and then said, “The Treasury of the True Dharma Eye of the tathagatas is manifested before us today. In its illumination even a piece of tile is radiant. When it is obscured, even pure gold loses its luster. In my hand is the scepter of authority. It will now kill and give life. If you are an accomplished adept in the practice of our school, then come forward and gain authentication!”

The monk came forward and said, “Far from the ancestral seat at Cuifeng, now expounding at Xuedou, do you still not know if it’s one or if it’s two?”

Xuedou said, “A horse cannot beat the wind for a thousand miles.”

The monk said, “In that case, the clouds disperse and the clear moon is above the households.”

Xuedou said, “A dragon-headed, snake-tailed fellow.”

A monk came forward, bowed, and then rose to ask, “Master, please respond.”

Xuedou then hit him.

The monk said, “Can’t you offer an expedient method?”

Xuedou said, “Don’t make the same mistake again.”

Another monk came forward, bowed, and then said, “Master, please respond.”

Xuedou said, “Two important cases.”

The monk said, “Master, please don’t respond.”

Xuedou then hit him.

A monk asked, “What is ‘blowing feather sword’?”

Xuedou said, “Arduous!”

The monk said, “Will you allow me to use it?”

Xuedou said, “Ssshhh! If you’re going to ask questions before the entire assembly, you should have attained being a true person. If you don’t have instantaneous vision, then there’s no use in asking questions. Thus it is said that, ‘It’s like a great bonfire. If you walk too close to it the portals of your face will be burned away.’ Or it’s like the great Taia Jeweled Sword. Whoever encounters it loses his body and life.159 When you take the Taia sword in your hand, the ancestral hall becomes cold, and in every direction for ten thousand miles all mental activity must cease. Don’t wait until you see the glimmer of the sword! Look! Look!”

Xuedou then got down from the seat and left the hall.

A monk came forward and bowed.

Xuedou said, “Monks of the congregation! Remember this monk’s huatou!”

Xuedou then left the hall.

A monk asked, “An ancient said, ‘Conceal the body in the Big Dipper.’ What does this mean?”

Xuedou said, “Hearing it a thousand times is not as good as seeing it once.”

Xuedou addressed the monks, saying, “If there is a Dharma-treasure swordsman present, then I invite you to demonstrate this to the congregation.”

A monk then came forward to ask a question. Before he could speak, Xuedou said, “Where are you going?”

Xuedou then left the hall.

Xuedou addressed the monks, saying, “Even if you experience the earth shaking and the sky raining flowers, how can that compare to going back to the monk’s hall and building a fire in the stove?”

The master then left the hall.

Xuedou addressed the monks, saying, “So vast that nothing is outside of it. So small that nothing is inside of it. Both open and closed; both diverse and unified. Due to the barbarian having cut off form, many students of the Zen world have turned around. For endless eons the gully has been dammed up and people have not understood.”

Xuedou then struck his staff on the ground and said, “Go back to the monks’ hall.”

Upon his death, Xuedou received the posthumous title “Great Teacher Clear Awakening.”