ZEN IRODALOM ZEN LITERATURE

« Zen index

« Home

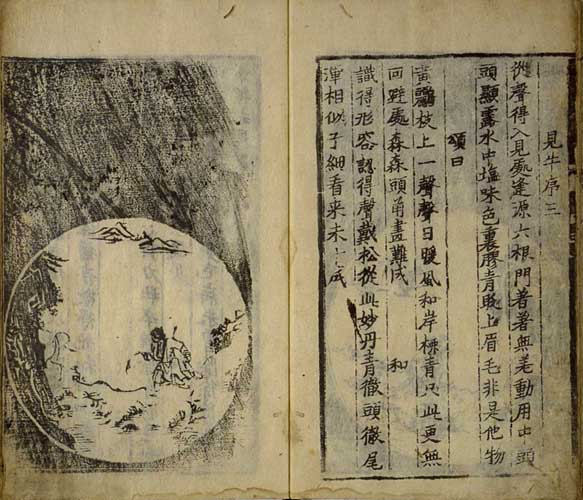

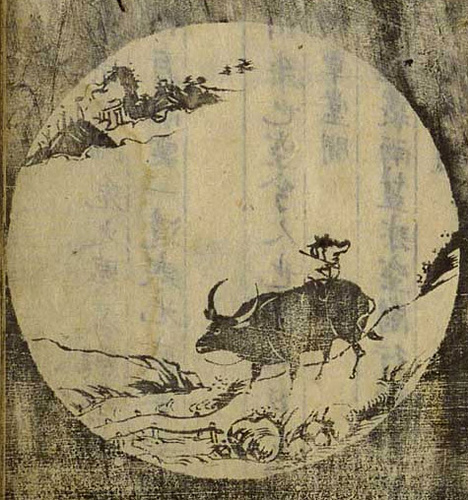

十牛圖 Shiniu tu [Jūgyūzu]

The Ten Oxherding Pictures

Introduction and verse by 廓庵師遠 Kuoan Shiyuan [Kakuan Shien], 12th century,

translated by D. T. Suzuki (鈴木大拙貞太郎 Suzuki Daisetsu Teitarō, 1870-1966)

« D. T. Suzuki's first version

D. T. Suzuki's second version:

"The Ten Cow-herding Pictures," translated by D. T. Suzuki, published

A) in The Eastern Buddhist (Original Series), Vol. 2. Nos. 3-4. 1923. pp. 176-195.

B) in Essays in Zen Buddhism, First Series. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1949, pp. 361-374.

"The ten pictures reproduced were specially prepared for the author by Reverend Seisetsu Seki, Abbot of Tenryuji, Kyoto."On this page: Original Gozan (五山) woodcut print source used for the reproductions of 関精拙 Seki Seisetsu (1877-1945).

住鼎州梁山廓庵和尚十牛圖 一卷 坿 入衆日用一卷

京都大學人文科學研究所所藏

(Kyoto University)

http://kanji.zinbun.kyoto-u.ac.jp/db-machine/toho/html/M0060001.html

THE TEN COW-HERDING PICTURES

THE attainment of Buddhahood or the realization of Enlightenment is what is aimed at by all pious Buddhists, though not necessarily during this one earthly life; and Zen, as one of the Mahāyāna schools, also teaches that all our efforts must be directed towards this supreme end. While most of the other schools distinguish so many steps of spiritual development and insist on one's going through all the grades successively in order to reach the consummation of the Buddhist discipline, Zen ignores all these, and boldly declares that when one sees into the inmost nature of one's own being, one instantly becomes a Buddha, and that there is no necessity of climbing up each rung of perfection through eternal cycles of transmigration. This has been one of the most characteristic tenets of Zen ever since the coming east of Bodhidharma in the sixth century. 'See into thy own nature and be a Buddha' has thus grown the watchword of the Sect. And this 'seeing' was not the outcome of much learning or speculation, nor was it due to the grace of the supreme Buddha conferred upon his ascetic followers; but it grew out of the special training of the mind prescribed by the Zen masters. This being so, Zen could not very well recognize any form of gradation in the attainment of Buddhahood. The 'seeing into one's nature' was an instant act. There could not be any process in it which would permit scales or steps of development.

But in point of fact, where the time- element rules supreme, this was not necessarily the case. So long as our relative minds are made to comprehend one thing after another by degrees and in succession and not all at once and simultaneously, it is impossible not to speak of some kind of progress. Even Zen as something possible of demonstration in one way or another must be subjected to the limitations of time. That is to say, there are, after all, grades of development in its study; and some must be said to have more deeply, more penetratingly realized the truth of Zen. In itself the truth may transcend all form of limitation, but when it is to be realized in the human mind, its psychological laws are to be observed. The 'seeing into thy nature' must admit degrees of clearness. Transcendentally we are all Buddhas just as we are, ignorant and sinful if you like; but when we come down to this practical life, pure idealism has to give way to a more particular and palpable form of activity. This side of Zen is known as its 'constructive' aspect, in contradistinction to its 'all-sweeping' aspect. And here Zen fully recognizes degrees of spiritual development among its followers, as the truth reveals itself gradually in their minds until the 'seeing into one's nature' is perfected.

Technically speaking, Zen belongs to the group of Buddhist doctrines known as 'discrete' or 'discontinuous' or 'abrupt' (tun in Chinese), in opposition to 'continuous' or 'gradual' (chien); and naturally the opening of the mind, according to Zen, comes upon one as a matter of discrete or sudden happening and not as the result of a gradual, continuous development whose every step can be traced and analysed. The coming of satori is not like the rising of the sun gradually bringing things to light, but it is like the freezing of water, which takes place abruptly. There is no middle or twilight condition before the mind is opened to the truth, in which there prevails a sort of neutral zone, or a state of intellectual indifference. As we have already observed in several instances of satori, the transition from ignorance to enlightenment is so abrupt, the common cur, as it were, suddenly turns into a golden-haired lion. Zen is an ultra-discrete wing of Buddhism. But this holds true only when the truth of Zen itself is considered, apart from its relation to the human mind in which it is disclosed. Inasmuch as the truth is true only when it is considered in the light it gives to the mind and cannot be thought of at all independent of the latter, we may speak of its gradual and progressive realization in us. The psychological laws exist here as elsewhere. Therefore when Bodhidharma was ready to leave China he said that Dōfuku got the skin, the nun Sōji got the flesh, and Dōiku the bone, while Yeka had the marrow (or essence) of Zen.

Nangaku, who succeeded the sixth patriarch, had six accomplished disciples, but their attainments differed in depth. He compared them with various parts of the body, and said: 'You all have testified to my body, but each has grasped a part of it. The one who has my eyebrows is the master of manners; the second, who has my eyes, knows how to look around; the third, who has my ears, understands how to listen to reasoning; the fourth, who has my nose, is well versed in the act of breathing; the fifth, who has my tongue, is a great arguer; and finally, the one who has my mind knows the past and the present. This gradation was impossible if 'seeing into one's nature' alone was considered; for the seeing is one indivisible act, allowing no stages of transition. It is, however, no contradiction of the principle of satori, as we have repeatedly asserted, to say that in fact there is a progressive realization in the seeing, leading one deeper and deeper into the truth of Zen, finally culminating in one's complete identification with it.

Lieh-tzŭ, the Chinese philosopher of Taoism, describes in the following passage certain marked stages of development in the practice of Tao:

'The teacher of Lieh-tzŭ was Lao-shang-shih, and his friend Pai-kao-tzŭ. When Lieh-tzŭ was well advanced in the teachings of these two philosophers, he came home riding on the wind. Yin-shêng heard of this and came to Lieh-tzŭ to be instructed. Yin-shêng neglected his own household for several months. He never lost opportunities to ask the master to instruct him in the arts [of riding on the wind]; he asked ten times, and was refused each time. Yin-shêng grew impatient and wanted to depart. Lieh-tzŭ did not urge him to stay. For several months Yin-shêng kept himself away from the master, but did not feel any easier in his mind. He came over to Lieh-tzŭ again. Asked the master, "Why this constant coming back and forth?" Yin-shêng replied, "The other day, I, Chang Tai, wished to be instructed by you, but you refused to teach me, which naturally I did not like. I feel, however, no grudge against you now, hence my presence here again."

'"I thought the other time," said the master, "you understood it all. But seeing now what a commonplace mortal you are, I will tell you what I have learned under the master. Sit down and listen! It was three years after I went to my master Lao-shang and my friend Pai-kao that my mind began to cease thinking of right and wrong, and my tongue talking of gain and loss, whereby he favoured me with just a glance. At the end of five years my mind again began to think of right and wrong, and my tongue to talk about gain and loss. Then for the first time the master relaxed his expression and gave me a smile. At the end of seven years I just let my mind think of whatever it pleased, and there was no more question of right and wrong, I just let my tongue talk of whatever it pleased, and there was no more question of gain and loss. Then for the first time the master beckoned me to sit beside him. At the end of nine years, just letting my mind think of whatever it pleased and letting my tongue talk of whatever it pleased, I was not conscious whether I or anybody else was in the right or wrong, whether I or anybody else gained or lost; nor was I aware of the old master's being my teacher or the young Pai-kao's being my friend. Both inwardly and outwardly I was advanced. It was then that the eye was like the ear, and the ear like the nose, and the nose like the mouth; for they were all one and the same. The mind was in rapture, the form dissolved, and the bones and flesh all thawed away; and I did not know how the frame supported itself and what the feet were treading upon. I gave myself away to the wind, eastward or westward, like leaves of a tree or like a dry chaff. Was the wind riding on me? or was I riding on the wind? I did not know either way.

'"Your stay with the master has not covered much space of time, and you are already feeling grudge against him. The air will not hold even a fragment of your body, nor will the earth support one member of yours. How then could you ever think of treading on empty space and riding the wind?"

'Yin-shêng was much ashamed and kept quiet for some time, not uttering even a word.'

The Christian and Mahommedan mystics also mark the stages of spiritual development. Some Sufis describe the 'seven valleys' to traverse in order to reach the court of Simburgh, where the mystic 'birds' find themselves gloriously effaced and yet fully reflected in the Awful Presence of themselves. The 'seven valleys' are: 1. The Valley of Search; 2. The Valley of Love, which has no limits; 3. The Valley of Knowledge; 4. The Valley of Independence; 5. The Valley of Unity, pure and simple; 6. The Valley of Amazement; and 7. The Valley of Poverty and Annihilation, beyond which there is no advance. According to St. Teresa, there are four degrees of mystic life: Meditation, Quiet, a numberless intermediate degree, and the Orison of Unity; while Hugo of St. Victor has also his own four degrees: Meditation, Soliloquy, Consideration, and Rapture. There are other Christian mystics having their own three or four steps of 'ardent love' or of 'contemplation'.

Professor R. A. Nicholson gives in his Studies in Islamic Mysticism a translation of Ibnu 'I-Fárid The Poem of the Mystic's Progress (Tá'iyya), parts of which at least are such exact counterparts of Buddhist mysticism as to make us think that the Persian poet is simply echoing the Zen sentiment. Whenever we come across such a piece of mystic literature, we cannot help being struck with the inmost harmony of thought and feeling resonant in the depths of human soul, regardless of its outward accidental differences. The verses 326 and 327 of the Tá'iyya read:

'From "I am She" I mounted to where is no "to", and I perfumed [phenomenal] existence by my returning:

'And [I returned] from "I am I" for the sake of an esoteric wisdom and external laws which were instituted that I might call [the people to God].'

The passage as it stands here is not very intelligible, but read the translator's comments which throw so much light on the way the Persian thought flows:

'Three stages of Oneness (ittihád) are distinguished here: 1. "I am She", i.e. union (jam') without real separation (tafriqa), although the appearance of separation is maintained. This was the stage in which al-Halláj said Ana 'I-Haqq, "I am God". 2. "I am I", i.e. pure union without any trace of separation (individuality). This stage is technically known as the "intoxication of union" (sukru 'I-jam'). 3. The "sobriety of union" (saḥwu 'I-jam'), i.e. the stage in which the mystic returns from the pure oneness of the second stage to plurality in oneness and to separation in union and to the Law in the Truth, so that while continuing to be united with God he serves Him as a slave serves his lord and manifests the Divine Life in its perfection to mankind.

'"Where is no 'to'", i.e. the stage of "I am I", beyond which no advance is possible except by means of retrogression. In this stage the mystic is entirely absorbed in the undifferentiated oneness of God. Only after he had "returned", i.e. entered upon the third stage (plurality in oneness), can he communicate to his fellows some perfume (hint) of the experience through which he has passed. "An esoteric wisdom", i.e. the Divine providence manifested by means of the religious law. By returning to consciousness, the "united" mystic is enabled to fulfil the law and to act as a spiritual director.'

When this is compared with the progress of the Zen mystic, as is pictorially illustrated and poetically commented in the following pages, we feel that the comments were written expressly for Zen Buddhism.

During the Sung dynasty a Zen teacher called Seikyo illustrated stages of spiritual progress by a gradual purification or whitening of the cow until she herself disappears. But the pictures, six in number, are lost now.1 Those that are still in existence, illustrating the end of Zen discipline in a more thorough and consistent manner, come from the ingenious brush of Kakuan, a monk belonging to the Rinzai school. His are, in fact, a revision and perfection of those of his predecessor. The pictures are ten in number, and each has a short introduction in prose, followed by a commentary verse, both of which are translated below. There were some other masters who composed stanzas on the same subjects using the rhymes of the first commentator, and some of them are found in the popular edition of "The Ten Cow-herding Pictures".

The cow has been worshipped by the Indians from very early periods of their history. The allusions are found in various connections in the Buddhist scriptures. In a Hinayana Sutra entitled "On the Herding of Cattle",2 eleven ways of properly attending them are described. In a similar manner a monk ought to observe eleven things properly in order to become a good Buddhist; and if he fails to do so, just like the cow-herd who neglects his duties, he will be condemned. The eleven ways of properly attending cattle are: 1. To know the colours; 2. To know the signs; 3. Brushing; 4. Dressing the wounds; 5. Making smoke; 6. Walking the right path; 7. Tenderly feeling for them; 8. Fording the streams; 9. Pasturing; 10. Milking; 11. Selecting. Some of the items cited here are not quite intelligible.

____________________

1

Since this book went to press I have come across an old edition of the spiritual cow-herding pictures, which end with an empty circle corresponding to the eighth of the present series. Is this the work of Seikyo as referred to in Kakuan Preface? The cow is shown to be whitening here gradually with the progress of discipline.

2

See also a Sūtra in the Anguttara Āgama bearing the same title which is evidently another translation of the same text. Also compare "The Herdsman, I", in The First Fifty Discourses of Gotama the Buddha, Vol. II, by Bhikkhu Śīlācāra. (Leipzig, 1913.) This is a partial translation of the Majjhima Nikāya of the Pāli Tripitaka. The eleven items as enumerated in the Chinese version are just a little differently given. Essentially, of course, they are the same in both texts. A Buddhist dictionary called Daizo Hossu gives reference on the subject to the great Mahāyāna work of Nāgārjuna, the Mahāprajñāpāramitā-Sūtra, but so far I have not been able to identify the passage.

In the Saddharma-pundarīka Sūtra, chapter iii., "A Parable", the Buddha gives the famous parable of three carts-- bullock-carts, goat-carts, and deer-carts--which a man promises to give to his children if they come out of a house on fire. The finest of the carts is the one drawn by bullocks or cows (goratha), which represents the vehicle for the Bodhisattvas, the greatest and most magnificent of all vehicles, leading them directly to the attainment of supreme enlightenment. The cart is described thus in the Sūtra: 'Made of seven precious substances, provided with benches, hung with a multitude of small bells, lofty, adorned with rare and wonderful jewels, embellished with jewel wreaths, decorated with garlands of flowers, carpeted with cotton mattresses and woollen coverlets, covered with white cloth and silk, having on both sides rosy cushions, yoked with white, very fair and fleet bullocks, led by a multitude of men.'

Thus reference came to be made quite frequently in Zen literature to the 'white cow on the open-air square of the village', or to the cow in general. For instance, Tai-an of Fu-chou asked Pai-chang, 'I wish to know about the Buddha; what is he?' Answered Pai-chang, 'It is like seeking for an ox while you are yourself on it.''What shall I do after I know?''It is like going home riding on it.''How do I look after it all the time in order to be in accordance with [the Dharma]?' The master then told him, 'You should behave like a cow-herd, who, carrying a staff, sees to it that his cattle won't wander away into somebody else's rice-fields.'

"The Ten Cow-herding Pictures" showing the upward steps of spiritual training is doubtless another such instance, more elaborate and systematized than the one just cited.

THE TEN STAGES OF SPIRITUAL COW-HERDING

I

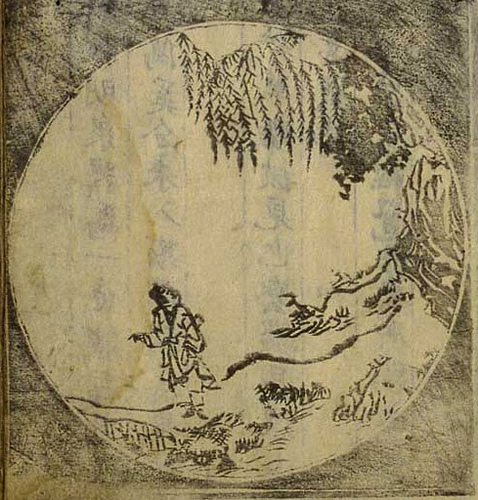

Looking for the Cow

She has never gone astray, so what is the use of searching her? We are not on intimate terms with her, because we have contrived against our inmost nature. She is lost, for we have ourselves been led out of the way through the deluding senses. The home is growing farther away, and byways and crossways are ever confusing. Desire for gain and fear of loss burn like fire, ideas of right and wrong shoot up like a phalanx.

Alone in the wilderness, lost in the jungle, he is searching, searching!

The swelling waters, far-away mountains, and unending path;

Exhausted and in despair, he knows not where to go,

He only hears the evening cicadas singing in the maple-woods.

II

Seeing the Traces of the Cow

By the aid of the Sutras and by inquiring into the doctrines he has come to understand something; he has found the traces. He now knows that things, however multitudinous, are of one substance, and that the objective world is a reflection of the self. Yet he is unable to distinguish what is good from what is not; his mind is still confused as to truth and falsehood. As he had not yet entered the gate, he is provisionally said to have noticed the traces.

By the water, under the trees, scattered are the traces of the lost:

Fragrant woods are growing thick -- did he find the way?

However remote, over the hills and far away, the cow may wander,

Her nose reaches the heavens and none can conceal it.

III

Seeing the Cow

He finds the way through the sound; he sees into the origin of things, and all his senses are in harmonious order. In all his activities it is manifestly present. It is like the salt in water and the glue in colour. [It is there, though not separably distinguishable.] When the eye is properly directed, he will find that it is no other thing than himself.

Yonder perching on a branch a nightingale sings cheerfully;

The sun is warm, the soothing breeze blows through the willows green on the bank;

The cow is there all by herself, nowhere is there room to hide her;

The splendid head decorated with stately horns, what painter can reproduce her?

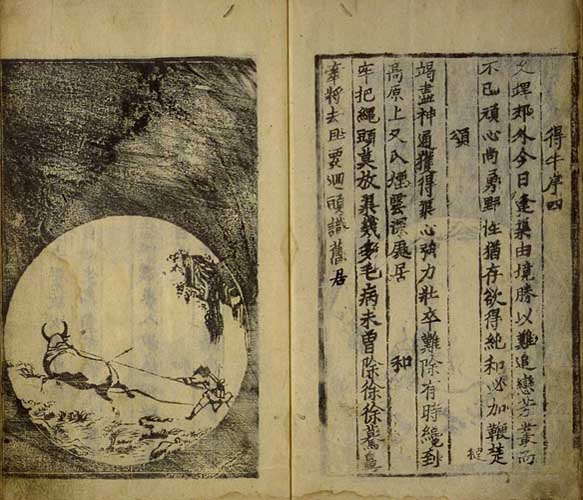

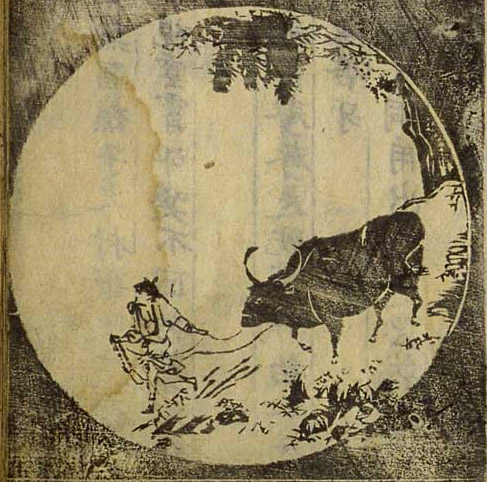

IV

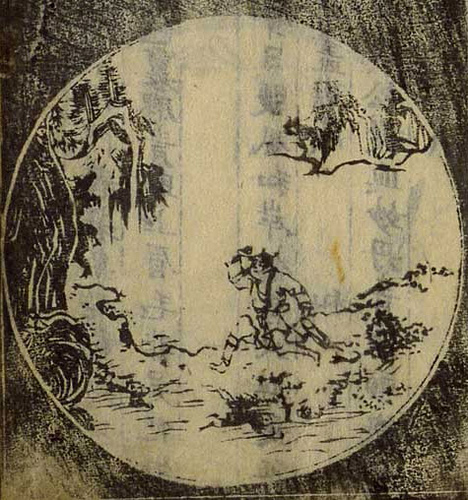

Catching the Cow

After getting lost long in the wilderness, he has found the cow and laid hand on her. But owing to the overwhelming pressure of the objective world, the cow is found hard to keep under control. She constantly longs for sweet grasses. The wild nature is still unruly, and altogether refuses to be broken in. If he wishes to have her completely in subjection, he ought to use the whip freely.

With the energy of his whole soul, he has at last taken hold of the cow:

But how wild her will, ungovernable her power!

At times she struts up a plateau,

When lo! she is lost in a misty, impenetrable mountain-pass.

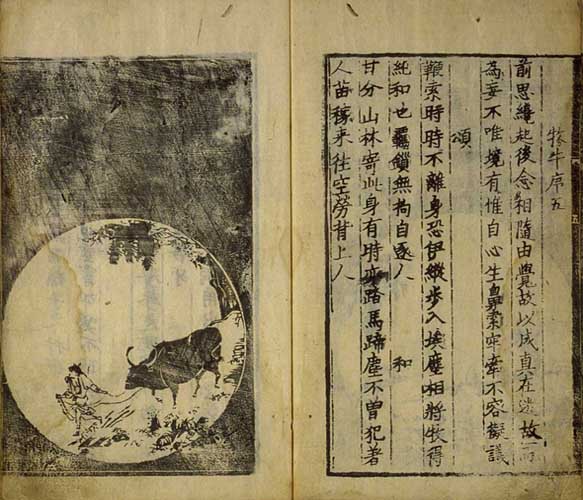

V

Herding the Cow

When a thought moves, another follows, and then another--there is thus awakened the endless train of thoughts. Through enlightenment all this turns into truth; but falsehood asserts itself when confusion prevails. Things oppress us not because of the objective world, but because of the self-deceiving mind. Do not get the nose-string loose; hold it tight, and allow yourself no indulgence.

Never let yourself be separated from the whip and the tether,

Lest she should wonder away into a world of defilement:

When she is properly tendered, she grows pure and docile,

Even without chain, nothing binding, she will by herself follow you.

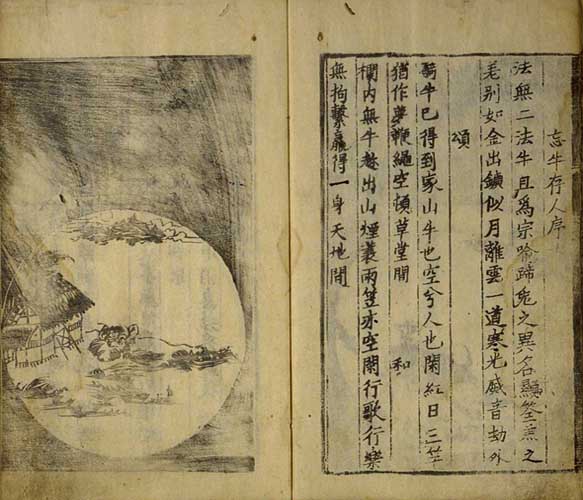

VI

Coming Home on the Cow's Back

The struggle is over; he is no more concerned with gain and loss. He hums the rustic tune of the woodman, he sings the simple song of the village-boy. Saddling himself on the cow's back, his eyes are fixed on the things not of this earth, earthly. Even if he is called to, he will not turn his head; however enticed, he will no more be kept back.

Riding the cow he leisurely wends his way home:

Enveloped in the evening mist, how tunefully the flute vanishes away!

Singing a ditty, beating time, his heart is filled with a joy indescribable!

That he is now one of those who know, need it be told?

VII

The Cow Forgotten, Leaving the Man Alone

Things are one and the cow is symbolic. When you know that what you need is not the snare or set-net but the hare or fish, it is like gold separated from dross, it is like the moon rising out of the clouds. The one ray of light serene and penetrating shines even before days of creation.

Riding on the cow he is at last back in his home,

Where lo! there is no more the cow, and how serenely he sits all alone!

Though the red sun is held up in the sky, he seems to be still quietly asleep;

Under a straw-thatched roof are his whip and rope idly lying beside him.

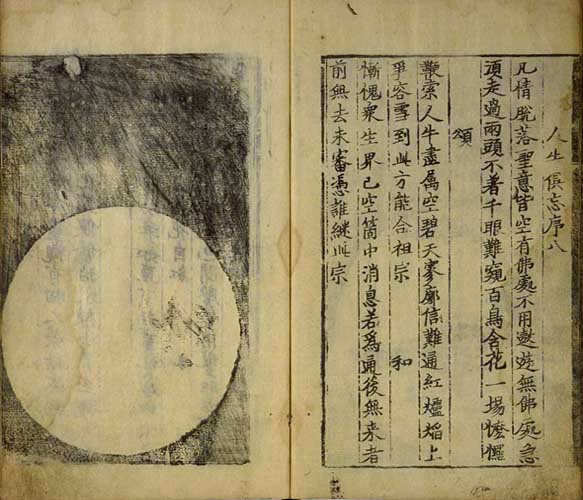

VIII

The Cow and the Man Both Gone out of Sight

All confusion is set aside, and serenity alone prevails; even the idea of holiness does not obtain. He does not linger about where the Buddha is, and where there is no Buddha he speedily passes on. When there exists no form of dualism, even the thousand-eyed one fails to detect a loophole. A holiness before which birds offer flowers is but a farce.

[Footnote: It will be interesting to note what a mystic

philosopher would say about this: "A man shall become truly poor

and as free from his creaturely will as he was when he was born.

And I say to you, by the eternal truth, that as long as ye desire

to fulfil the will of God, and have any desire after eternity and

God; so long are ye not truly poor. He alone has true spiritual

poverty who wills nothing, knows nothing, desires nothing." --

From Eckhart as quoted by Inge in "Light, Life, and Love".]

All is empty, the whip, the rope, the man, and the cow:

Who has ever surveyed the vastness of heaven?

Over the furnace burning ablaze, not a flake of snow can fall:

When this state of things obtains, manifest is the spirit of the ancient master.

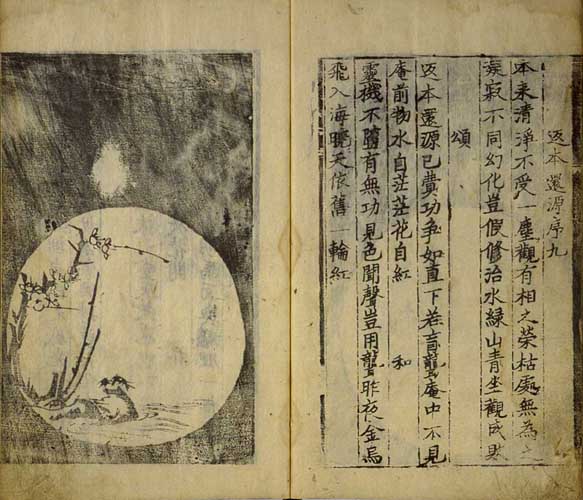

IX

Returning to the Origin, Back to the Source

From the very beginning, pure and immaculate, he has never been affected by defilement. He calmly watches growth and decay of things with form, while himself abiding in the immovable serenity of non-assertion. When he does not identify himself with magic-like transformations, what has he to do with artificialities of self-discipline? The water flows blue, the mountain towers green. Sitting alone, he observes things undergoing changes.

To return to the Origin, to be back at the Source--already a false step this!

Far better it is to stay home, blind and deaf, straightway and without much ado.

Sitting within the hut he takes no cognizance of things outside,

Behold the water flowing on--whither nobody knows; and those flowers red and fresh--for whom are they?

X

Entering the City with Bliss-Bestowing Hands

His humble cottage door is closed, and the wisest knows him not. No glimpses of his inner life are to be caught; for he goes on his own way without following the steps of the ancient sages. Carrying a gourd he goes out into the market; leaning against a stick he comes home. He is found in company with wine-bibbers and butchers; he and they are all converted into Buddhas.

Barechested and barefooted, he comes out into the marketplace;

Daubed with mud and ashes, how broadly he smiles!

There is no need for the miraculous power of the gods,

For he touches, and lo! the dead trees come into full bloom.