ZEN IRODALOM ZEN LITERATURE

« Zen index

« Home

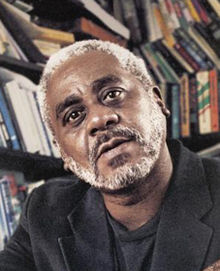

Charles Richard Johnson (1948-)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_R._Johnson

PDF: Turning the wheel: essays on Buddhism and writing

by Charles Johnson

Scribner, 2003, pp. 22-25.

One of the perennially enchanting documents of Ch'an

(Zen) Buddhism is the "Ten Oxherding Pictures," which

inspired my second novel, Oxherding Tale (1982). These drawings

depict the spiritual stages of Zen development that lead to

enlightenment by portraying the search of a young herdsman

for his lost ox (self). Each illustration is followed by commentary

in prose and verse. The ten stages shown are (1) Seeking

the Ox; (2) Finding the Tracks; (3) First Glimpse of the Ox; (4)

Catching the Ox; (5) Taming the Ox; (6) Riding the Ox Home;

(7) Ox Forgotten, Self Alone; (8) Both Ox and Self Forgotten;

(9) Returning to the Source; and (10) Entering the Marketplace

with Helping Hands. It is this final panel that speaks significantly

to the question of Perfect Conduct.The version of the Oxherding Pictures important for this

discussion was created in 1150 C.E. by Zen master K'uo-an

Shih-yuan (Kakuan Shien in Japanese). Some earlier versions of

the Oxherding Pictures offered only five or eight drawings, usually

ending with an empty circle (Both Ox and Self Forgotten) ,

which fit nicely the arhat ideal of Theravada Buddhism. "This

implied," says Philip Kapleau, "that the realization of Oneness

(i.e., the effacement of every conception of self and other) was

the ultimate goal of Zen. But Kakuan, feeling this to be incomplete,

added two more pictures beyond the circle to make it clear

that the Zen man of the highest spiritual development lives in

the mundane world of form and diversity' and mingles with the

utmost freedom among ordinary men, whom he inspires with

his compassion and radiance to walk in the Way of the Buddha."

Shih-yuan's final, tenth picture is accompanied by this

commentary:10 / Entering the Marketplace with Helping Hands /

The gate of his cottage is closed and even the wisest cannot

find him. His mental panorama has finally disappeared. He

goes his own way, making no attempt to follow the steps of

earlier sages. Carrying a gourd, he strolls into the market;

leaning on his staff, he returns home. He leads innkeepers

and fishmongers in the Way of the Buddha.Kapleau's gloss on the commentary of this tenth image deserves

examination:In ancient China gourds were commonly used as wine bottles.

What is implied here therefore is that the man of the

deepest spirituality is not adverse to drinking with those

fond of liquor in order to help them overcome their delusion.

... In Mahayana Buddhism . . . the man of deep

enlightenment (who may be and often is the layman) gives

off no 'smell' of enlightenment, no aura of 'saintliness'; if he

did, his spiritual attainments would be regarded as still

deficient. Nor does he hold himself aloof from the evils of

the world. He immerses himself in them whenever necessary

to emancipate men from their follies, but without

being sullied by them himself. In this he is like the lotus, the

symbol in Buddhism of purity and perfection, which grows

in mud yet is undefiled by it.Often we hear that the attainment of Oneness, or being

awakened, is "nothing much" (for the belief in separateness was

a chimera in the first place). Like Bunan, the Oxherder discovers

that "The moon's the same old moon / The flowers

exactly as they were." He will take a drink. And perhaps eat

meat. But to none of this is he attached. Nor does he crave them.

Like the abbot I met in Thailand, he does not fret about "good"

or "bad" karma, because in his conduct all he is capable of are

acts in accordance with ahimsa, which he does not name or

judge as "good," no more than the lotus bothers to name the

natural act of its efflorescence. And the Oxherder has a sense of

humor and irony. How could he not? He knows that, despite all

he has attained through a lifetime of practice, he is still an

embodied being and, as such, will experience until the day of his

death a residual stain of dualism, a tincture of samsara, and

traces of suffering, which he recognizes when they arise in his

consciousness. All that he "lets go," and when he dies, falling like

a raindrop back into the sea, it is unlikely he will return (or

return too often) on the Wheel of remanifestation. He is, in a

sense, a refugee—homeless and groundless. He watches the

ceaseless play of his thoughts, but is not naive enough to believe

there is a thinker. (For a Buddhist, Descartes asserted but he did

not prove his claim "I think, therefore I am," because all that one

can empirically verify is that "There is thinking going on.") He

is alone with others who are also refugees or tourists with no

solid basis for security, and nothing permanent in this world. He

pilgrimages through the Marketplace (the realm that turns on

four, dualistic pairs of opposites: "getting and losing, disrepute

and fame, blame and praise, happiness and suffering") with

fearlessness, probity, desirelessness (nishpriha), transcendent

joy, and he delights in the suchness of everyday things:How wonderful, how marvelous!!

I fetch wood, I carry water!To the innkeepers and fishmongers, the Oxherder appears,

in one sense, as nothing special, with no sanctimonious stink of

self-righteousness on him since all sentient beings have Buddha-nature

and dwell in "an inescapable network of mutuality." But

through his example—his compassion toward all beings, his

gentle speech, and his unshakable peace and happiness—he

points them toward their own possibilities.

PDF: Oxherding Tale (novel, 1982)