ZEN IRODALOM ZEN LITERATURE

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

宏智正覺 Hongzhi Zhengjue (1091–1157)

& 萬松行秀 Wansong Xingxiu (1166-1246)

從容錄 Congrong lu

(Rōmaji:) Wanshi Shōgaku & Banshō Gyōshū: 從容録 Shōyō-roku

(English:) Book of Serenity / The Book of Equanimity / The Book of Composure / The Record of Going Easy / Encouragement (Hermitage) Record

(Magyar:) Hung-cse Cseng-csüe & Van-szung Hszing-hsziu: Cung-zsung lu / A nyugalom könyve* / Higgatag feljegyzések (Az megbékélés könyve)**

*©Hadházi Zsolt **©Terebess Gábor

Compiled in 1223. Full title is 萬松老人評唱天童覺和 尙頌古從容庵錄 Wansong laoren pingchang Tiantong Jue heshang songgu Congrong an lu (Old Man Wansong's Evaluations of Tiantong Jue's Versed Comments on Old Cases).

宏智正覺 Hongzhi Zhengjue (1091–1157) & 萬松行秀 Wansong Xingxiu (1166-1246)

請益錄 Qingyi lu

(Rōmaji:) Wanshi Shōgaku & Banshō Gyōshū: 請益録 Shin'eki-roku

(English:) Record of Seeking Additional Instruction

(Magyar:) Hung-cse Cseng-csüe & Van-szung Hszing-hsziu: Csing-ji lu / Kitartó keresések*

*©Terebess Gábor

Full title is 萬松老人評唱天童覺和尚拈古請益錄 Wansong laoren pingchang Tiantong Jue heshang niangu Qingyi lu (Old Man Wansong's Singing Appraisal of Monk Tiantong Jue's Bringing Up the Old Record of Further Inquiries).

In Chinese: X1307 http://www.cbeta.org/cgi-bin/goto.pl?linehead=X67n1307_p0495b20

Tartalom |

Contents |

Higgatag feljegyzések A nyugalom könyve Hongzhi válogatás A Buddha lényegi működése A zazen tűje Mokusóka A Csendes Megvilágító Zeisler István: A csendes felébredés zenje |

從容録 Congrong lu [Shōyō-roku]

坐禪箴 Zuochan zhen [Zazenshin]

默照銘 Mozhao ming [Mokushōmei; Mokushōka]

宏智禪師廣錄 Hongzhi chanshi guanglu [Wanshi zenji kōroku]

|

A koan collection, at the core of which are one hundred "verse comments on old cases" (juko 頌古) composed by Wanshi Shōkaku (C. Hongzhi Zhengjue 宏智正覺, 1091–1157), an eminent monk in the Soto 曹洞 lineage who was also known as Reverend Kaku of Tendō (Tendō Kaku Oshō, C. Tiantong Jue Heshang 天童覺和尚). The full title of the text is Congrong Hermitage Record : Old Man Banshō's Evaluations of Tendō Kaku's Verse Comments on Old Cases (Banshō rōjin hyōshō tendō kaku juko shōyōroku 萬松老人評唱天童覺和尚頌古從容録). The Congrong Hermitage Record as we have it today took shape in 1223 at the hand of Zen master Banshō Gyōshū (C. Wansong Xingxiu 萬松行秀, 1166–1246), who was living in the Congrong Hermitage (Shōyō an , C. Congrong an 從容菴) at the Blessings Repaying Monastery (Hōonji 報恩寺) in Yanjing. To each root case (honsoku 本則) and attached verse comment (song 頌) found in the core text by Tendō Kaku, Banshō added (1) a prose "instruction to the assembly" (shishu 示衆) which precedes the citation of the case and serves as a sort of introductory remark; (2) a prose commentary on the case; and (3) a prose commentary on the verse. Moreover, Banshō added interlinear capping phrases to each case and verse.

http://global.sotozen-net.or.jp/eng/library/glossary/individual.html?key=congrong_hermitage_recordThe Ts'ung-jung Record, we see that it is similar in arrangement

to the Blue Cliff Collection, and that the koans it contains have basically

the same internal structure. At the core of the text is a collection of verses on

old cases (sung-ku), one hundred in all, attributed to T'ien-t'ung Chüeh, a

prominent abbot of the T'ien-t'ung Monastery whose full name was Hung-chih

Cheng-chüeh (1091-1157). That core collection, which may have circulated

independently from Hung-chih's discourse record, is called Hung-chih's

Verses on Old Cases (Hung-chih sung-ku). The Ts'ung-jung Record as we know

it today took shape in 1223 under the hand of Ch'an master Wan-sung Hsinghsiu

(1166-1246), who was living in the Ts'ung-jung Hermitage (Ts'ung-jungan)

at the Pao-en Monastery in Yen-ching. To each old case and attached

verse found in the core text, Wan-sung added: (i) a prose "instruction to the

assembly" (shih-chung) which precedes the citation of the case and serves as a

sort of introductory remark; (2) a prose commentary on the case, introduced

by the words "the teacher said" (shih ytin); and (3) a prose commentary on

the verse, also introduced by "the teacher said." Moreover, Wan-sung added

interlinear capping phrases to each case and verse.

The headings "instruction to assembly" and "the teacher said" give the

impression that Wan-sung's introductory remarks and prose commentaries on

each case were delivered orally in a public forum and recorded by his disciples.

It is not impossible that Wan-sung actually gave a series of lectures on Hung32

chih's Verses on Old Cases which, when recorded and compiled by his disciples,

resulted in the Ts'ung-jung Record. Such lectures would have been extremely

difficult to follow, however, unless the members of the audience had the text

of Hung-chih's Verses on Old Cases in hand to consult as the master spoke.

Perhaps that was the case, but the complex structure of the Ts'ung-jung Record

is such that I am inclined to view it as a purely literary production, albeit one

that employs headings normally found in ostensibly verbatim records of oral

performances.

http://awakenvideo.org/pdf/777/The%20Koan%20Texts%20and%20Contexts.pdf從容錄 Congrong lu

6 fasc.; T 2004; full title is Congrong Hermitage Record: Old Man Wansong's Evaluations of Tiantong Xue's Versed Comments on Old Cases 萬松老人評唱天童覺和 尙 頌古從容庵錄 [Wansong Laoren pingchang Tiantongjue Heshang songgu Congrong an lu / Manshō Rōnin Hyōshō Tendōkaku Washō juko Shōyō an roku] . A basic text of the Caodong school 曹洞宗 of Chan, which consists of one hundred versified kōan dialogs compiled by Hongzhi Zhengjue 宏智正覺 (1091–1157) (the Hongzhi Songgu 宏智頌古 ), an eminent monk in the Caodong 曹洞 lineage who was also known as Reverend Jue of Tiantong 天童覺和 尙 . It includes the commentary of Wansong Xingxiu 萬松行秀 (1166–1246), published in 1224, with the present version based on a republication done in 1607. To each root case 本則 and attached verse comment 頌 found in the core text by Tiantong Jue, Wansong added (1) a prose "instruction to the assembly" 示衆 which precedes the citation of the case and serves as a sort of introductory remark; (2) a prose commentary on the case; and (3) a prose commentary on the verse. Moreover, Wansong added interlinear capping phrases to each case and verse.

http://www.buddhism-dict.net/ddb/pcache/5fid(b5f9e-5bb9-9304).htmlA whole independent genre of Chan literature evolved out of the practice of commenting on the gongan stories of past masters. Many Song Chan masters (or their students) compiled collections of old gongan cases, attaching the master's own brief comments to each. These collections were called niangu (picking up the old [cases or masters]) when a prose commentary was attached and songgu (eulogizing the old [cases or masters]) when the commentary was in poetic form. Such collections were themselves sometimes further subject to another master's commentaries, resulting in rather complex and somewhat confusing pieces of literature. Hongzhi's verses on one hundred gongan cases (a songgu commentary), for example, were further commented on by Wansong Xingxiu (1166–1246) and published as the Congrong lu (Record of equanimity). The treatment of each case in this work begins with an introduction by Wansong followed by the gongan case in question, with brief and often cryptic interlinear commentary by Wansong. Then comes a longer prose commentary on the case by Wansong, followed by Hongzhi's verse on the case, again with brief interlinear commentary by Wansong. Finally comes a prose commentary by Wansong on Hongzhi's verse and on the case in general.

(Morten Schlütter)

In Chinese:

萬松老人評唱天童覺和尚頌古從容庵錄

Wansong laoren pingzhang Tiantong Jue heshang songgu Congrongan lu

Congrong Hermitage Record of the Commentaries by Old Wansong on the Case and Verse [Collection] by Reverend Jue of Tiantong [Mountain]

T 2004.48.262a20–c5

http://www.baus-ebs.org/sutra/fan-read/003/03-015.htm

http://www.suttaworld.org/gbk/sutra/lon/other48/2004/2004.htm

http://www.buddhism-dict.net/ddb/pcache/5fid(b5f9e-5bb9-9304).html

http://www.yuezang.me/epub/2730/TableOfContents.xhtml?locale=zh-Hans

http://tripitaka.cbeta.org/ko/T48n2004

http://www.cbeta.org/result2/T48/T48n2004.htm

![]() DOC: The Book of Serenity

DOC: The Book of Serenity

Translated by Thomas Cleary (Chinese-English bilingual edition)

![]() DOC: The Record of the Temple of Equanimity

DOC: The Record of the Temple of Equanimity

Translated by Gregory Wonderwheel

![]() DOC: Shōyō-roku (Book of Equanimity)

DOC: Shōyō-roku (Book of Equanimity)

[only main cases; names in Romaji]

Translated by the Sanbô Kyôdan Society

![]() PDF: Shôyôroku (Book of Equanimity)

PDF: Shôyôroku (Book of Equanimity)

[Introductions, Cases, Verses]

Translated by the Sanbô Kyôdan Society

PDF: Shôyôroku (Book of Equanimity) Case 1 to Case 100

Teisho by Yamada Kôun (1907-1989)

Translation of Yamada Koun Roshi's Teisho

on the Shoyoroku (Book of Equanimity)

Foreword of the Editor to the Homepage Edition of the Shôyôroku-Teisho The Shôyôroku, translated as "Book of Equanimity" or so metimes as "Book of Serenity", is a famous koan collection in the Soto line. Originally Master WANSHI Shôgaku (1091-1157) collected 100 koans and made a verse to each one of them sometime in the middle of 12 th century; then Master BANSHÔ Gyôshû (1166-1246) supplied the collection with Instructions, Commentaries etc. in 1223/24. In the following teisho, only the "Instruction", "Case" and "Verse" are dealt with according to the traditional manner. YAMADA Kôun Roshi delivered his teisho on Case 1 of the Shôyôroku on 24 April 1978; his teisho on Case 100 was given on 23 May 1985. All teisho on the Shôyôroku in those five years were recorded into tapes, and they ar e now being transcribed into a written form. The project of the English translation of Yama da Kôun Roshi's Teisho of the Shôyôroku (Book of Equanimity) was launched in late 2002, and now at last we are ready to start mounting the work successively on our homepa ge. Our first presentation is rather incomplete, but we ask for your tolerance and understanding for the time being. The excellent translation is the work of Paul SHEPHERD; the manuscript was proof-read and edited by SATO Migaku with the Japanese original at hand. A big number of people assisted financially for the project, and their names are listed separately with deep appreciation. SATO Migaku |

PDF: The Book of Equanimity: Illuminating Classic Zen Koans

Translated by Gerry Shishin Wick,

Wisdom Publications, 2005, 320 pages

Versions of the koans based on Maezumi Taizan's translations, with commentaries by Gerry Shishin Wick

Table of Contents

Foreword by Bernie Glassman . . . xi

Acknowledgments . . . xiii

Introduction . . . 1Case 1: The World-Honored One Ascends the Platform . . . 11

Case 2: Bodhidharma’s Vast Emptiness . . . 13

Case 3: An Invitation for the Patriarch . . . 16

Case 4: The World-Honored One Points to the Earth . . . 18

Case 5: Seigan’s Cost of Rice . . . 20

Case 6: Baso’s White and Black . . . 22

Case 7: Yakusan Takes the High Seat . . . 25

Case 8: Hyakujo’s Fox . . .28

Case 9: Nansen Cuts a Cat . . . 31

Case 10: Joshu Sees Through the OldWoman . . . 34

Case 11: Ummon’s Two Sicknesses . . . 37

Case 12: Jizo Plants the Field . . . 40

Case 13: Rinzai’s Blind Donkey . . . 43

Case 14: Attendant Kaku Serves Tea . . . 46

Case 15: Kyozan Plants His Mattock . . . 49

Case 16: Mayoku Thumps His Staff . . . 51

Case 17: Hogen’s Hair’s-Breadth . . . 54

Case 18: Joshu’s Dog . . . 57

Case 19: Ummon’s Mount Sumeru . . . 60

Case 20: Jizo’s “Not Knowing Is the Most Intimate” . . . 63

Case 21: Ungan Sweeps the Ground . . . 66

Case 22: Ganto’s Bow and Shout . . . 69

Case 23: Roso Faces theWall . . . 72

Case 24: Seppo’s Poison Snake . . . 75

Case 25: Enkan’s Rhinoceros-Horn Fan . . . 78

Case 26: Kyozan Points to Snow . . . 81

Case 27: Hogen Points to the Blind . . . 84

Case 28: Gokoku’s Three Shames . . . 87

Case 29: Fuketsu’s Iron Ox . . . 90

Case 30: Daizui’s Kalpa Fire . . . 94

Case 31: Ummon’s Free-Standing Pillar . . . 98

Case 32: Kyozan’s State of Mind . . . 100

Case 33: Sansho’s Golden Carp . . . 103

Case 34: Fuketsu’s Speck of Dust . . . 106

Case 35: Rakuho’s Acquiescence . . . 108

Case 36: Baso’s Illness . . . 112

Case 37: Isan’s Karmic Consciousness . . . 114

Case 38: Rinzai’s True Man . . . 117

Case 39: Joshu’s Bowl-Washing . . . 120

Case 40: Ummon’s White and Black . . . 123

Case 41: Rakuho’s Last Moments . . . 126

Case 42: Nanyo’s Washbasin . . . 130

Case 43: Razan’s Arising and Vanishing . . . 132

Case 44: Koyo’s Garuda Bird . . . 134

Case 45: The Sutra of Complete Awakening . . . 138

Case 46: Tokusan’s Completion of Study . . . 141

Case 47: Joshu’s Cypress Tree . . . 144

Case 48: Vimalakirti’s Nonduality . . . 147

Case 49: Tozan Offers to the Essence . . . 150

Case 50: Seppo’s “What’s This?” . . . 154

Case 51: Hogen’s “By Boat or Land” . . . 158

Case 52: Sozan’s Dharmakaya . . . 161

Case 53: Obaku’s Dregs . . . 164

Case 54: Ungan’s Great Compassionate One . . . 168

Case 55: Seppo the Rice Cook . . . 171

Case 56: Mishi’s White Rabbit . . . 174

Case 57: Genyo’s One Thing . . . 178

Case 58: The Diamond Sutra’s Reviling . . . 181

Case 59: Seirin’s Deadly Snake . . . 184

Case 60: Ryutetsuma’s Old Cow . . . 187

Case 61: Kempo’s One Stroke . . . 190

Case 62: Beiko’s No Enlightenment . . . 193

Case 63: Joshu Asks About Death . . . 196

Case 64: Shisho’s Transmission . . . 199

Case 65: Shuzan’s New Bride . . . 203

Case 66: Kyuho’s Head and Tail . . . 206

Case 67: The Avatamsaka Sutra’sWisdom . . . 210

Case 68: Kassan’s Slashing Sword . . . 214

Case 69: Nansen’s Cats and Cows . . . 217

Case 70: Shinzan Questions the Nature of Life . . . 220

Case 71: Suigan’s Eyebrows . . . 223

Case 72: Chuyu’s Monkey . . . 226

Case 73: Sozan’s Requited Filial Piety . . . 229

Case 74: Hogen’s Substance and Name . . . 232

Case 75: Zuigan’s Permanent Principle . . . 235

Case 76: Shuzan’s Three Phrases . . . 238

Case 77: Kyozan Holds His Own . . . 241

Case 78: Ummon’s Farm Rice-Cake . . . 245

Case 79: Chosha Advances a Step . . . 248

Case 80: Ryuge Passes the Chin Rest . . . 252

Case 81: Gensha Comes to the Province . . . 256

Case 82: Ummon’s Sounds and Shapes . . . 259

Case 83: Dogo’s Nursing . . . 262

Case 84: Gutei’s One Finger . . . 265

Case 85: The National Teacher’s Seamless Tomb . . . 268

Case 86: Rinzai’s Great Enlightenment . . . 271

Case 87: Sozan’s With orWithout . . . 275

Case 88: The Shurangama’s Unseen . . . 278

Case 89: Tozan’s No Grass . . . 282

Case 90: Kyozan Respectfully Declares It . . . 286

Case 91: Nansen’s Peony . . . 289

Case 92: Ummon’s One Treasure . . . 292

Case 93: Roso’s Not Understanding . . . 295

Case 94: Tozan’s Illness . . . 299

Case 95: Rinzai’s One Stroke . . . 302

Case 96: Kyuho’s Disapproval . . . 305

Case 97: Emperor Ko’s Cap . . . 309

Case 98: Tozan’s Heed . . . 312

Case 99: Ummon’s Bowl and Pail . . . 315

Case 100: Roya’s Mountains and Rivers . . . 318Appendix: Masters Referenced in The Book of Equanimity

I. Ancient Chinese and Japanese Ancestors . . . 321

II. Indian Ancestors and Bodhisattvas . . . 327

III. Modern Ancestors and Teachers . . . 328

Suggested Further Reading . . . 329

Case 1

The World-Honored One Ascends the Platform

Preface to the assembly

Close the gate and snooze—that’s how to treat a superior person. Reflection,

abbreviation, and elaboration are used for middling and inferior ones.

How can you stand for someone to ascend the high seat and scowl? If anyone

around here doesn’t agree, step forward. I have no doubts about him.Main case

Attention! One day the World-Honored One ascended the platform and

took his seat. Manjushri struck the sounding post and said: “When you realize

the Dharma-King’s Dharma, the Dharma-King’s Dharma is just as is.” At

that, the World-Honored One descended from the platform.Appreciatory verse

Do you see the true manner of the primal stage?

Mother Nature goes on weaving warp and woof;

the woven old brocade contains the images of spring—

nothing can be done about the Spring God’s (Manjushri) outflowing.Attention! When the Buddha, also known as theWorld-Honored One, ascends

the platform it means he’s ready to give a discourse on the Dharma. In this

koan,Manjushri, the bodhisattva of wisdom who is renowned for cutting delusion

with Dharma words, announces the beginning of the talk with the statement:

“When you realize the Dharma-King’s Dharma, the Dharma-King’s

Dharma is just as is.” And then, the Buddha descends the platform; his discourse

is over. What more could he say? Even Manjushri’s announcement is

unnecessary. He’s saying too much; he’s “leaking” or as the verse says he is

“outflowing.”

When you truly understand the Dharma, it’s just thus, just this; it’s as is. All

kinds of words and phrases have been invented in Zen to express thusness or

“as-is”-ness, but none are needed. Don’t add anything extra. Just let everything

be as it is. That’s liberation. But letting everything be as is, is difficult

for us because we’re always trying to fiddle around with things, always adding

something, wishing something were taken away. We’re always putting

another head atop our own.

I know people who want to be a lion but feel just like a frightened kitten—

and not only that, they feel like a frightened kitten frightened about

feeling like a frightened kitten! But the Dharma-King’s Dharma is as is; if

you’re frightened, be frightened, leave it at that and don’t add anything extra.

What does it mean to let it all be and let it all go? And what about when

you can’t let it go, what then?Well, if you’re holding on, hold on. That’s liberation

too. Let the Dharma-King’s Dharma be as is.

This seems straightforward, but the subtlety comes in each moment: Each

moment, how do you practice the Dharma-King’s Dharma? And let me ask

you this: Why do you practice Zen? If you think you’re going to become

something else, you’re fooling yourself. If you think that you don’t need to

practice zazen because everything is perfect as it is, that is an erroneous view.

The first line of the verse says, “Do you see the true manner of the primal

stage?” This is inviting us to realize the truth of ultimate reality. Is that

ultimate reality theWorld-Honored One ascending the platform, or is it the

World-HonoredOne descending the platform? If you let the light of ultimate

reality blind your eye, it’s hard to see. If it does not blind your eye, then it’s

hard to let go. If you see it, don’t dwell there.

The Dharma-King’s Dharma is as is. If you continue to be frightened and to

maintain your judgments about being frightened, then you are not truly feeling

fright. You are holding on to your opinions. By accepting your experience without

judgments, you allow transformation to take place. I cannot count the times

I heardMaezumi Roshi say, “Appreciate your life.” Appreciating your lifemeans

that the Dharma-King’s Dharma is just as is. From that place you can embrace

yourself and appreciate yourself. It is not a matter of being a superior or inferior

person. It is not a matter of Manjushri’s outflowing. Just let everything be

as is and appreciate every moment of this life as the life of the Dharma-King.

Case 2

Bodhidharma’s Vast Emptiness

Preface to the assembly

Benka’s three offerings did not prevent his being punished: If a luminous

jewel were thrown at them, few are the men who would not draw their

swords. For an impromptu guest, there is not an impromptu host; he’s provisionally

acceptable but not absolutely acceptable. If you can’t grasp rare,

valuable treasure, let’s toss in a dead cat’s head and see.Main case

Attention! EmperorWu of Ryo asked the great master Bodhidharma, “What

is the ultimate meaning of the holy truth of Buddhism?” Bodhidharma replied,

“Vast emptiness. No holiness.” The Emperor asked, “Who stands here before

me?” Bodhidharma replied, “I don’t know.” The Emperor was baffled. Thereafter,

Bodhidharma crossed the river, arrived at Shorin and faced the wall for

nine years.Appreciatory verse

Emptiness, no holiness—

the questioner’s far off.

Gain is to swing the axe and not harm the nose;

loss is to drop the pot and not look back.

In solitude he sits cool at Shorin;

in silence the Right Decree’s fully revealed.

The autumn’s lucid and the moon’s a turning frosty wheel;

the MilkyWay’s pale, and the Big Dipper’s handle hangs low.

In line the robe and bowl handed on to descendents

henceforth are medicine to men and devas.

Emperor Wu had heard about Bodhidharma, the Indian monk who brought

Zen to China in the sixth century, and summoned him to his court. In preparation

for meeting with this great bodhisattva, the emperor must have asked

his advisors what was the single most important question to ask a great monk.

When he meets Bodhidharma, he presents that question. Yet Bodhidharma’s

answer to him—”Vast emptiness. No holiness.”—surprises and confuses the

emperor so utterly that he wonders if the man before him is the great and

learned monk he had expected and not an imposter—hence his second question.

And Bodhidharma’s thunderous reply is, simply, “I don’t know.”

What is this vast emptiness?What is this “I don’t know”?What does empty

mean? It doesn’t mean blackness or nihilism or nothingness, and it isn’t the

emptiness we complain about when we say “I feel empty.” Everything is

impermanent; nothing is fixed. One’s own form is empty of any fixed thing.

Realizing this emptiness, experiencing it directly, is one of the most important

aspects of our practice. There is no fixed thing that is the self—nothing

to grasp onto, no firm ground upon which to stand, no right understanding

to attain. As soon as you think you’ve grabbed “it,” you have lost “it.” Realizing

“it” directly, tremendous freedom is manifest.

When self-aggrandizing thoughts arise—or even negative thoughts that

affirm the illusion of an independent self—we grab onto them instead of just

letting them go. Why do we grab onto them? If we didn’t reinforce the illusion

of a fixed self, what would we be? What would be left?

There is an old Zen expression that is appropriate here: ”Even the water

melting from the snow-capped peaks finds its way to the ocean.” It finds its

way without even knowing the direction and against all obstacles!We think

that we need to control everything. Out of ignorance we keep affirming this

false self to feel secure and to feel that we are in control of our life.

We believe that we are the content of our thoughts (and our opinions,

beliefs, feelings, and reactions). We resist seeing that we ourselves are “vast

emptiness” and thus are denying our deep unlimited nature. The Buddha realized

that there is no gap between ourselves and others.We are all one body.

And by not recognizing who we are, we’re creating a chasm between ourselves

and others that is greater than the Grand Canyon, and being unable to

cross this chasm makes us miserable. But even so, we feel secure in our own

misery because it is familiar to us, it makes us feel in control.

Commenting on this case, one ancient Zen master said, “Leaving aside

the ultimate meaning for the moment, what do you want with the holy

truth?” What are you going to do with it? Another master said, “If you just

end attachments, there’s no holy understanding.” The Third Ancestor said,

“Don’t seek after the truth, just don’t cherish your opinions.” Just let the

clouds of delusion disperse. If you don’t cherish your delusions, then wisdom

will shine through naturally. One of the scriptures says, “If you create an

understanding of holiness, you will succumb to all errors.” How many wars

have been fought in the name of an understanding of what is holy? What

kind of holiness is that? If you create an understanding of holiness, if you

know—right there, you’re stuck in the mud. As soon as you know, that knowing

becomes dualistic, and as soon as it becomes dualistic it no longer corresponds

to reality.

Yasutani Roshi said, “When you make Bodhidharma’s ‘I don’t know’ your

own, it does not break into consciousness. If you know it, at a single stroke

it’s gone.” When you make it your own, it’s a part of your flesh, bones, and

blood. But if you describe it, it becomes something else.

Relating to this case, Yasutani Roshi wrote this poem:Holy reality, emptiness.

The man, unknowing.

Spring breeze and autumn moon speak heavenly truth.

Reverent monks building temples to no merit.

Emperor Wu, how could you know the willows’ new green?How could you know the willows’ new green? You’re so busy trying to figure

it out, you’re missing the buds under your own nose.

So what is this not knowing? There are all kinds of “I don’t know.” In this

case, this “I don’t know” snatches everything away. We can point at it, but

how can we really express it? It is like a mute serving as a messenger to us.

But if we really open ourselves up, we can receive the message nonetheless.

But what is given? What is received? What is maintained?

When Bodhidharma left the emperor, he spent nine years facing a wall.

What was he doing for those nine years? If you understand this koan, you can

answer without hesitation.

Case 3

An Invitation for the Patriarch

Preface to the assembly

By the activity existing before even a hint of this kalpa, a blind turtle faces

the fire. By the phrase that’s transmitted outside the scriptures, a mortar’s rim

spouts a flower. Tell me: is there something to receive, maintain, read, and

recite?Main case

Attention! The ruler of a country in Eastern India invited the Twenty-Seventh

Ancestor, Hannyatara, for a midmorning meal. The ruler asked him,

“Why don’t you read the sutras?” The Ancestor replied, “This poor follower

of the Way, when breathing in does not dwell in the realm of skandhas, and

when breathing out is not caught up in the many externals. Always do I thus

turn a hundred thousand million billion rolls of sutras.”Appreciatory verse

Cloud rhino sports with the moon and glows embracing its beams;

wooden horse plays in the spring, unfettered and fleet.

Beneath his brows, two chill blue eyes—

what need to read sutras as though piercing oxhide!

Bright white mind transcends vast kalpas,

a hero’s strength tears through nested enclosures.

The subtle round hub-hole turns marvelous activities.

When Kanzan forgets the road whence he came,

Jittoku will lead him by hand to return.

Hannyatara, Bodhidharma’s teacher and the twenty-seventh Ancestor in our

lineage, doesn’t dwell in the realm of form, sensation, perception, conception,

and consciousness—the skandhas—and so he doesn’t get caught in a

notion of a fixed separate self. Inhaling and exhaling, there is no inside or

outside. Each breath reveals the sutra.

Sutra usually refers to the teachings of the Buddha, but a sutra could be

anything that is undeniably true.With each breath Hannyatara revolves the

sutras. Breathing in, breathing out, the fundamental holy truth of the primary

principle is revealed.

Hannyatara turns a nice phrase: “This poor follower of the Way.” To be

poor is to have nothing and to hold onto nothing. Being poor in that way

gives us the richness of not being constrained by external conditions.

This is a prescription for all of our dis-ease: Breathe in without attaching

to internals, breathe out without attaching to externals.When we do that, we

manifest clear, unclouded vision. But if we add anything to that simple practice,

it becomes something else entirely. To learn simple breathing in and

breathing out takes steady years of meditation. Breathe in and do not create

a false self; breathe out and don’t perturb the world or be perturbed by the

world—the ultimate meaning of the holy truth is revealed.

The verse says “A hero’s strength tears through nested enclosures.” Breathing

in, you’re a minister. Breathing out, you’re a general. These “nested enclosures”

are all of the cloaks that we wear. “I am a teacher.” “I am a Buddhist.” “I

am an artist.” Breathe in and you see past the teacher. Breathe out and you see

beyond the artist. The hero’s strength tears through these wrappers that we

put around ourselves. Each time we breathe it is a new sutra.

In this way whatever you’re doing, you’re revolving the sutras. Picking the

weeds, changing a diaper, and making a flower arrangement are a hundred

thousand million billion rolls of sutras. Completely become breathing in and

breathing out and that’s all there is. In that moment, where’s Hannyatara? If

you realize “this poor follower of theWay” you are free to come and go. But

if you don’t, you’re using counterfeit money to buy stock in a corrupt corporation.

Case 4

The World-Honored One Points to the Earth

Preface to the assembly

When a speck of dust is raised, the great earth is fully contained in it. It’s very

well to open new territory and extend your lands with horse and spear.Who

is this person who can be master in any place and meet the source in everything?Main case

Attention!When theWorld-HonoredOne was walking with his disciples he

pointed to the ground and said, “It would be good to erect a temple here.”

The god Indra took a blade of grass and stuck it in the ground and said, “The

temple has been erected.” TheWorld-Honored One smiled faintly.Appreciatory verse

On the hundred grass-tips, boundless spring—

taking what’s at hand, use it freely.

Buddha’s sixteen foot golden body of manifold merit

spontaneously extending a hand, enters the red dust—

within the dust he can be host

coming from another world, naturally he’s a guest.

Wherever you are be content with your role—

dislike not those more adept than you.Part of experiencing growth in our life requires developing a larger vision

unconstrained by our usual, limited mind, like Indra and Buddha. Doing so

requires great awareness.We all have blind spots, and we project our world

view from those dark places. That projection inevitably distorts our relations

with others, with the world, and with ourselves.We need to practice awareness

in order to develop clarity and to perceive the difference between reality

and distortions.We also need perseverance because without it we will not

generate the heat necessary to melt our self-grasping ignorance.

Suppose you saw a black raven flying by, and everybody in the room said,

“That’s not a black raven. That’s a white snowy egret.” You’d say, “No it’s not.

It’s a black raven!” “No, everybody here except you says it’s a snowy egret.” You

might see certain things with the clarity developed from your Zen practice,

and yet everyone is telling you something else. This often happens when you

visit close relatives. Someone might say, “This Zen stuff, sitting on the cushion

all these hours—it’s a total waste of time!” What do you say? Whenever

visitors would say something argumentative to him, Maezumi Roshi would

give them space for their opinions. He would respond, “It could be so.”

The verse says, “Taking what’s at hand, use it freely.” Just put aside all of

your ideas, standards, and judgments, then look at the world with your larger

vision and see what arises. How can you manifest the sixteen foot golden

body of the Buddha? How can you erect a temple from a blade of grass? The

Bible says that your body is your temple. A piece of grass is your temple too.

All dharmas in the ten directions are your body and your temple. But, as

Master Bansho says in commenting on this case, “Repairs won’t be easy.”

The verse also says: “Wherever you are, be contented with your role.

Don’t dislike those that are more adept than you.” No matter how good you

are there is always somebody better. No matter how bad you are there is

always somebody worse. How can we be everything that we want to be?

Everywhere life is sufficient. Just be who you are, and don’t restrict it.

從容録 Higgatag feljegyzések (Az egyensúly könyve)

Fordította: Terebess Gábor

*A higgatag a magyar nyelvújítás szóképzése, pl. Arany János használja higgadt értelemben Murány ostroma c. elbeszélő költeményében. (A fordító megj.)

第二則達磨廓然 2. Bódhidharma ürességeA Liang-dinasztia Vu-ti császára kihallgatta a nagy tanítót, Bódhidharmát:

– Mi a végső értelme a szent igazságnak? - kérdezte.

– Minden üres, nem szent – mondta Bódhidharma.

– Akkor ki áll itt előttem?

– Nem tudni.

A császár nem értette. Bódhidharma később átkelt a Jangce vizén, majd Saolinban kilenc évig ült a falnak fordulva.

第九則南泉斬猫 9. Nan-csüan macskát öl

Egyszer a Nyugati és a Keleti Csarnok szerzetesei veszekedtek egy kismacskán. Nan-csüan mester felvette a macskát és elébük tartotta:

– Szóljatok érte egy szót, vagy megölöm!

A szerzetesek zavartan hallgattak, mire Nan-csüan kettévágta a macskát.

Estefelé megérkezett Csao-csou, és Nan-csüan elmesélte neki, mi történt. Csao-csou levette a szalmabocskorát, feltette a fejére és indult kifelé.

– Ha itt lettél volna – sóhajtott Nan-csüan –, megmented azt a macskát.

Az illusztráció art deco tapéta-vágat.

第十則臺山婆子 10. A Vutaj-hegy anyója

Egy szerzetes a Vutaj-hegyre zarándokolt. Útközben megkérdezett egy öreganyót, merre tartson.

– Csak egyenesen előre.

A szerzetes úgy is ment.

– Ez is csak arra tér le – mormogta utána az öreganyó.

A szerzetes elmesélte Csao-csounak, hogy járt.

– Kipuhatolom én azt az öreganyót – mondta Csao-csou.

Másnap maga is megkérdezte tőle, merre menjen.

– Csak egyenesen előre.

A mester úgy is tett.

– Ez is csak arra tér le – mormogta utána is az öreganyó.

Amikor Csao-csou visszatért, a szerzetesek már várták.

– Rajtakaptam az öreganyót – biztosította őket Csao-csou.

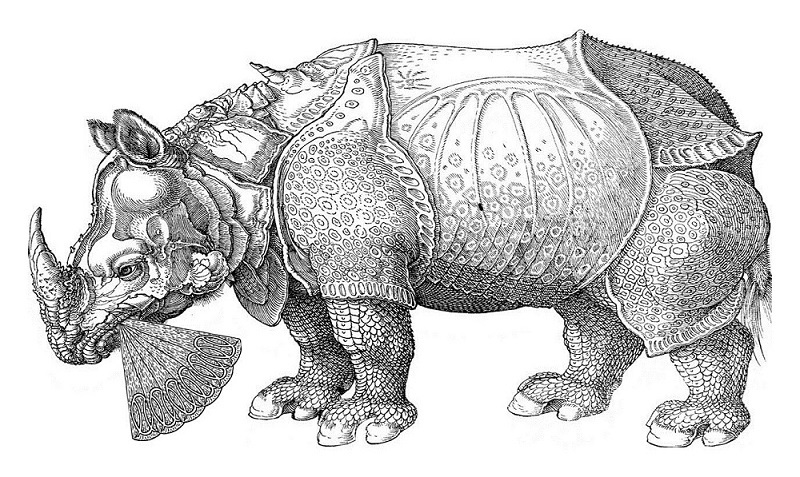

第二十五則鹽官犀扇 25. Jen-kuan orrszarvúcsont legyezője

Jen-kuan szólt a segédjének, hozza oda az orrszarvúcsont legyezőjét.

– Eltört – mondta a szerzetes.

– Akkor hozd ide az orrszarvút! – mondta Jen-kuan.

A szerzetes nem válaszolt.

Az illusztráció Albrecht Ajtósi Dürer (1471-1528) Rinocérosza felhasználásával Terebess Pál munkája