ZEN FESTMÉNYEK ZEN PAINTING

« Zen illusztrációk

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

佐藤禅忠 Satō Zenchū (1883–1935)

Pen name: 空華道人 Kūge Dōnin

43 suibokuga 水墨画, bokuga 墨画 or more colloquially sumi-e 墨絵. Lit. water-ink painting. Painting in sumi 墨 (black ink) in dark and light shades on paper.

For

D.

T. Suzuki

THE TRAINING OF THE ZEN BUDDHIST MONK (PDF)

The Eastern Buddhist Society,

Kyoto, 1934

Zenchū Satō entered the Myōshinji monastery (妙心寺, Kyoto) in 1908, coming from Tōkeiji (東慶寺, Kamakura), the temple in which D.T. Suzuki used to live.

Satō Zenchū's Dharma Lineage:

[…]

白隱慧鶴 Hakuin Ekaku (1686-1769)

峨山慈棹 Gasan Jitō (1727-1797)

隱山惟琰 Inzan Ien (1751-1814)

太元孜元 Taigen Shigen (1768-1837)

儀山善來 Gisan Zenrai (1802-1878)

洪川宗温 Kōsen Sōon (1816-1892) [今北 Imakita]

洪岳宗演 Kōgaku Sōen (1859-1919) [釋 / 釈 Shaku]

佐藤禅忠 Satō Zenchū (1883-1935) [Pen name: 空華道人 Kūge Dōnin]

朝比奈宗源 Asahina Sōgen (1891-1979)

井上禅定 Inoue Zenjō (1911-2006)

Illustrations created at the monastery of

円覚寺 Engakuji in Kamakura

I. INITIATION

1. Monk Starting on Pilgrimage

[When

travelling, Zen monks have two bags. One hangs around the neck and rests on the

chest; the other is on the back like a knapsack.]

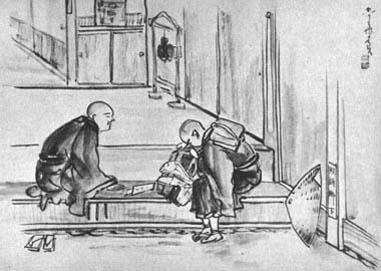

2. Asking for Admittance

3. Admittance Refused

4. Night in the Lodging Room

5. Initiated to the Zendo

6. Introduced to Roshi

II. LIFE OF HUMILITY

7. Takuhatsu-ing in the Streets

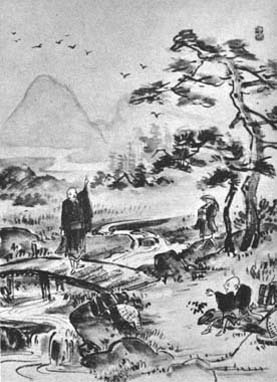

8. Monthly Collection of Rice

9. Takuhatsu-ing for Daikon

III. LIFE OF LABOUR

10. Wood-gathering

11. Sweeping

12. Gardening

13. Wrestling

IV. LIFE OF SERVICE

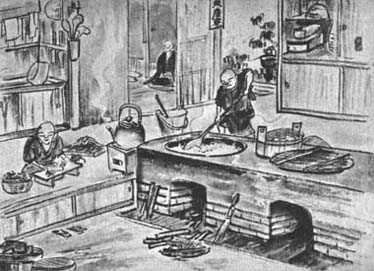

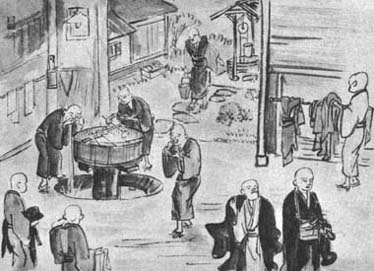

14. Cooking

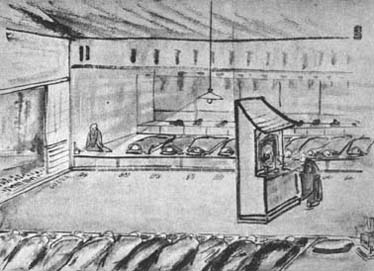

15. Dining Room

16. Nursing the Sick

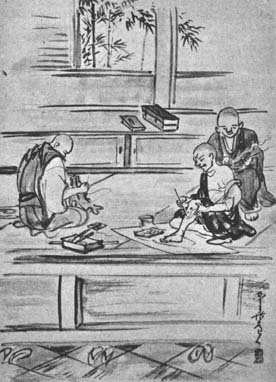

17. Sewing and Moxa-burning

18. Shaving

19. Washing

20. Bath-room

21. Work of Service

V. LIFE OF PRAYER AND GRATITUDE

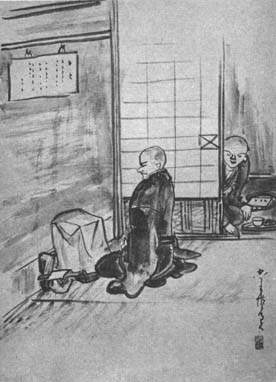

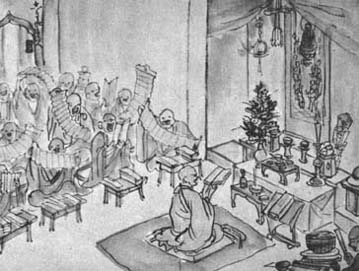

22. The Revolving of the Prajnaparamita Sutra

23. The Feeding of the Hungry Ghosts

VI. LIFE OF MEDITATION

24. The Front Door of the Zendo

25. The Rear Door of the Zendo

26. Kinhin (Walking Exercise)

27. Bedding Put up

28. Good Night to the Holy Monk

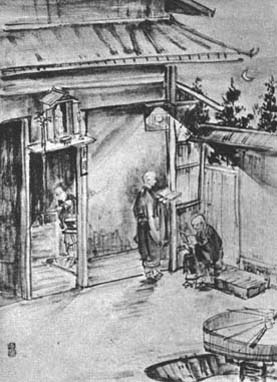

29. Morning Wash

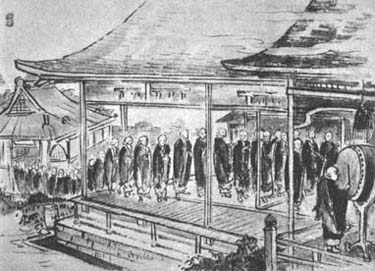

30. Monks Filing up

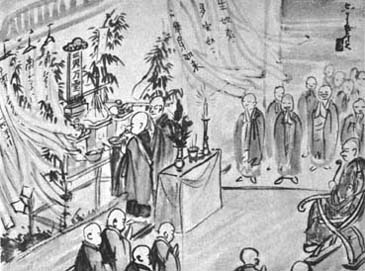

31. Roshi Ready for a Koza

32. Meditation Posture

33. Ready for a Zen Interview

34. Interview with Roshi

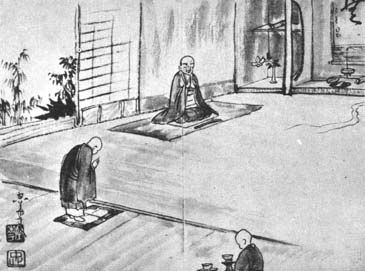

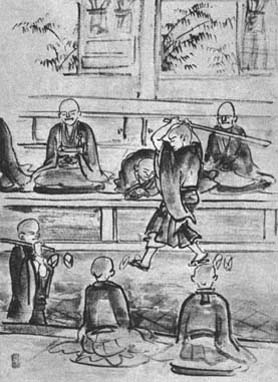

35. Deeds of the Utmost Kindness

36. The Warning Staff

37. Deeply Absorbed in Meditation

38. Monks Looking for Zen Passages

39. Seeing Off a Senior Monk

40. Zen Monks on Pilgrimage

41. Tea-ceremony with Roshi

42. Term-end Examination

43. Monk Striking the Large Bell

Satō Zenchū's Dharma Lineage

[…]

白隱慧鶴 Hakuin Ekaku (1686-1769)

峨山慈棹 Gasan Jitō (1727-1797)

隱山惟琰 Inzan Ien (1751-1814)

太元孜元 Taigen Shigen (1768-1837)

儀山善來 Gisan Zenrai (1802-1878)

洪川宗温 Kōsen Sōon (1816-1892) [今北 Imakita]

洪岳宗演 Kōgaku Sōen (1859-1919) [釋 / 釈 Shaku]

佐藤禅忠 Satō Zenchū (1883–1935)

Paintings by 佐藤禅忠 Satō Zenchū

Pen name: 空華道人 Kūge Dōnin

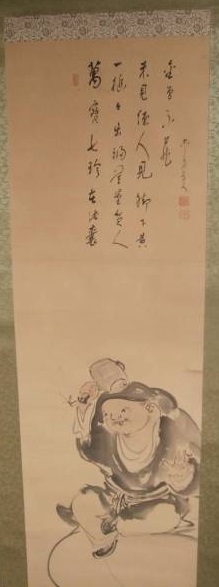

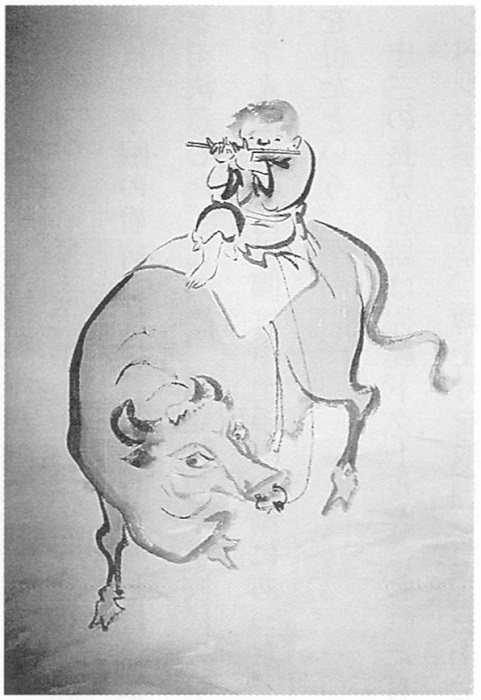

布袋図 Hotei (Budai)

安心第一 Relief is first. 空華道人Kūge Dōnin.

Temple: The 円覚寺 Engaku-ji branch. The abbot (bw. 1919-1935) of 東慶寺 Tōkei-ji (Kamakura), the sub-temple of Engaku-ji.

Pen name: Kūge Dōnin. He received priest ordination from 釈宗演 (Shaku) Kōgaku Sōen* (1860-1919) who was the head abbot of Engaku-ji branch. He studied Zen painting by himself.

Paper Dimension /cm: 37×35.4

Whole Dimension /cm: 124.6×48.4

Style: Horizontal silk mounting. Tea ceremony style.*Sōen was head priest of the Tōkeiji from 1905 until his

death in 1919, when he was given the title of Restoring

Founder of the Temple (chūkō kaizan). Matsu-ga-oka

Bunko, the library of his distinguished disciple, Suzuki

Daisetz (1870-1966) is located at the top of a stone stair-

way behind the temple.

Sōen was followed by his disciple Satō Zenchū (1883-

1935), the abbot in residence during the Great Earthquake

of 1923. After his death the Tōkeiji was administered for

six years by Asahina Sōgen (1891-1979), abbot of the

Jōchiji, and after 1941,head of the Engakuji. Zenchū's

disciple, Inoue Zenjō (1911-2006), who pursued his studies

and Zen training during this time, became resident abbot

of the Tōkeiji in 1941.

達磨図 Daruma (Bodhidharma)

廓然無聖 Being empty, there is no such thing as the holy truth. 空華道人 Kūge Dōnin.

Temple: The 円覚寺 Engaku-ji branch. The abbot (bw. 1919-1935) of 東慶寺 Tōkei-ji (Kamakura), the sub-temple of Engaku-ji.

Pen name: Kūge Dōnin. He received priest ordination from 釈宗演 (Shaku) Kōgaku Sōen (1860-1919) who was the head abbot of Engaku-ji branch. He studied Zen painting by himself.

Paper Dimension /cm: 123×29.5

Whole Dimension /cm: 202×42.6

Style: Vertical silk mounting. Normal style.

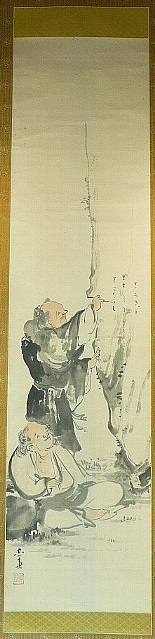

寒山拾得図 Kanzan & Jittoku (Hanshan & Shide)

136.5cm×33.3cm

鍾馗図 Shōki (Zhong Kui)

114.0×31.0cm

大黒図 Daikoku

is variously considered to be the god of wealth, or of the household, particularly the kitchen. He is recognised by his wide face, smile, and a flat black hat. He is often portrayed holding a golden mallet called an Uchide no kozuchi, otherwise known as a magic money mallet, and is seen seated on bales of rice, with mice nearby signifying plentiful food.

中古 掛軸 大幅 佐藤禅忠 蘆葉達磨

Daruma

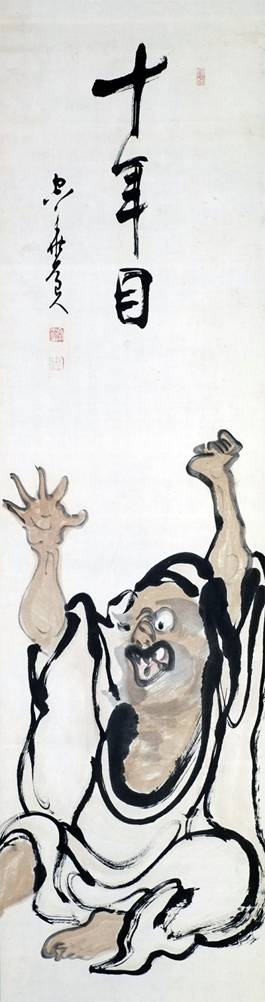

佐藤禅忠の作品「十年目」

「十牛図」

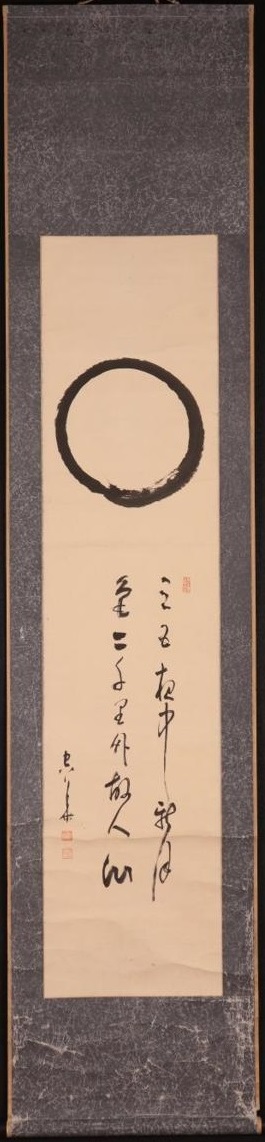

円相 Ensō (Circle)

鎌倉 東慶寺住職 空華道人/佐藤禅忠 『三聖人』 画賛 絹

The Vinegar Tasters is a traditional subject in Chinese religious and philosophical painting. The concept of the painting depicts the three founders of China’s three major religious and philosophical traditions: Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism. The painting engulfs a huge amount of wisdom and knowledge, and an interesting allegory.

We see the Buddha, Confucius, and Laozi standing around a vat full of vinegar, each one of the three masters dip their finger and take a taste of the vinegar. The expression on each man’s face shows his individual reaction, with each man representing a philosophical and religious teaching, the vinegar representing the “essence of life, and the reaction represent each teaching’s overview towards life and its essence. The Buddha is depicted having a bitter look on his face, Confucius with a sour expression, but we find Laozi wearing a smile of satisfaction.

Buddhism, as it is practiced today, was heavily influenced and shaped by Siddhartha Gautama, who lived a very sheltered and extravagant life growing up. As he neared his thirties it is said that he became aware of all the ugliness in the world, and this prompted him to leave his home in search of enlightenment, achieving it when he was thirty-five years old. Several interpretations grew out of the Buddha’s reaction to the taste of the vinegar; one interpretation is that Buddhism, being concerned with the self, viewed the vinegar as a polluter of the body due to its extreme and intense flavor. Another interpretation for the reaction, and the one I personally favor, is that Buddhism reports the life as it is, in which vinegar is vinegar and isn’t naturally sweet on the tongue, rather it acquires an extreme bitter taste. Trying to represent vinegar, which is a metaphor here for the essence of life, as sweet is ignoring and denying what it truly is.

Confucius saw life as sour, in need of rules to correct the degeneration of people and believed that the present was out of step of the past and that the government had no understanding of the way of the universe, in which the right response would be the reverence of the ancestors and their tradition. Confucius, being concerned with the outside world, viewed the vinegar as “polluted wine”.

Now we come to Laozi’s smile, and satisfactory look, with an excerpt from ‘The Tao of Pooh’ a book by Benjamin Hoff:

To Laozi, the harmony that naturally existed between heaven and earth from the very beginning could be found by anyone at any time, but not by following the rules of the Confucianists. As he stated in his Tao Te Ching, the “Tao Virtue Book,” earth was in essence a reflection of heaven, run by the same laws — not by the laws of men. These laws affected not only the spinning of distant planets, but the activities of the birds in the forest and the fish in the sea. According to Laozi, the more man interfered with the natural balance produced and governed by the universal laws, the further away the harmony retreated into the distance. The more forcing, the more trouble. Whether heavy or light, wet or dry, fast or slow, everything had its own nature already within it, which could not be violated without causing difficulties. When abstract and arbitrary rules were imposed from the outside, struggle was inevitable. Only then did life become sour.To Laozi, the world was not a setter of traps but a teacher of valuable lessons. Its lessons needed to be learned, just as its laws needed to be followed; then all would go well. Rather than turn away from “the world of dust,” Laozi advised others to “join the dust of the world.” What he saw operating behind everything in heaven and earth he called Tao, “the Way.”A basic principle of Laozi’s teaching was that this Way of the Universe could not be adequately described in words, and that it would be insulting both to its unlimited power and to the intelligent human mind to attempt to do so. Still, its nature could be understood, and those who cared the most about it, and the life from which it was inseparable, understood it best.In The Vinegar Tasters, Laozi is found smiling, why? Well, as we’ve said before the vinegar found in the allegory represents life, and certainly in reality, must certainly have an unpleasant taste, as the expressions on the faces of the other two men indicate. Yet, living in harmony and accordance with life and the Tao, this understanding transforms what others may perceive as negative into something positive. “From the Taoist point of view, argues Benjamin Hoff, sourness and bitterness come from the interfering and unappreciative mind. Life itself, when understood and utilized for what it is, is sweet. That is the message of The Vinegar Tasters.”