ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

遂翁元盧 Suiō Genro (1717-1789)

Suiō Genro (1717-1789) became a disciple of Hakuin at the age of 30, and after the death of his master, took over the Shōinji Temple. His first name was 慧牧 Eboku. He entered Myōshinji Temple at the age of 48, adopted the title of Suiō, and changed his name to Genro. He also had the alias Futo and used alternative characters for his name Suiō until the prime of his life. A liberal-minded person, he preferred poetry, alcohol, chess and painting to meditating and reading scriptures, and was said to have been a friend of Ikeno Taiga.

Two of Hakuin's chief disciples and heirs began to study under him: Tōrei Enji (1712–1792) in 1743, and Suiō Genro 遂翁元盧 (1717–1789) in 1746. Tōrei would be appointed as Hakuin's successor as the abbot of Ryūtakuji 龍沢寺, a temple Hakuin had himself constructed. Suiō would become the abbot of Shōinji 松蔭寺, after Hakuin's retirement in 1764. They were together known as the “two divine legs [eminent students] of Hakuin.”

Suiō Genro (1717-1789)

by Stephen Addiss

In: The art of Zen : paintings and calligraphy by Japanese monks, 1600-1925

New York : H.N. Abrams, 1989. pp. 138-142, notes p. 211.

Born in Shirnotsuke (present-day Tochigi), Suiō may have been the illegiti-

mate son of a daimyo.He became a pupil of Hakuin at about the age of thirty

and studied with the master for twenty years. Nevertheless, he did not reside

at Shōin-ji but lived some distance away in Nishi-aoshima. During these years,

Suiō came to Shōin-ji only when there was a Zen meeting, and as he practiced

zazen at night, no one knew of his diligence but his teacher, Hakuin.Suiō had a free and untrammeled spirit. One day, as he left Shōin-ji after a

meeting, a fellow pupil ran after him and said that Hakuin had called for him

to return. Suiō paid no attention and continued on to his home. He was also

fond of the board game go and of drinking sake.1 Nevertheless, the mutual

admiration between Hakuin and Suiō was very great. Suiō once commented

that "even a strongly egocentric monk will practice hard and reach enlighten-

ment if he studies with Hakuin. This is because there are many thorny bushes

surrounding the Way of Hakuin; one cannot attack and cannot retreat, so one

puts down the helmet and takes down the flag. Other masters do not have these

thorns, so they cannot stop the monk's egocentricity.The most famous story about Suiō concerns his return from a Zen meeting

given by Hakuin at Tenshō-in in Kuwana. On his way home, Suiō's boat

capsized in Shichiri harbor during a violent storm. Suiō thought that he had

sunk a great distance under the sea, but just at that moment he rose to the

surface as though lifted by invisible hands. A fishing boat then rescued him

from the roiling waters, and he believed he had escaped death by a miracle.

This story later grew into a legend in which Suiō calmly meditated at the

bottom of the Bay of Ise for several days after the shipwreck until he was

hauled up in a net by fishermen who thought they must have captured a giant

octopus. When they discovered the monk sitting in zazen, the fishermen were

naturally amazed.Hakuin greatly respected Suiō and appointed him his successor at Shōin-ji;

at Hakuin's funeral, Suiō and Tōrei conducted the memorial services. It was

Suiō who initiated the restoration of Ryutaku-ji after it had been burned, and

he persuaded Tōrei to return and take charge of the temple and its rebuilding

program. Yet Suiō told prospective Zen pupils who came to him that he was

just a lazy monk, and he recommended that they go to Ryutaku-ji to study

with Tōrei; he did take on some pupils, however, and over the course of their

careers both masters trained a number of followers. On the seventh anniver-

sary of Hakuin's death, Tōrei and Reigen asked Suiō to conduct the commem-

orative meeting, which more than two hundred monks and laymen attended.

Suiō went on to lead other large meetings, and he became famous as a Zen

teacher not only of monks but also of the general public.

It was Suiō's character to be both spontaneous and generous. He once told

his followers that an old proverb says that it is better to fail because of slowness

rather than quickness, but he believed the opposite: if one must fail, it would

be better to fail from quickness. Examples of his generosity are many,

including his encouragement of little-known monks to take prominent roles at

major meetings that he held for Zen followers.2Suiō was fond of painting, and he developed his own variations of the style

of Hakuin's "early" period. Suiō was also a friend of the Nanga master Ike

Taiga, and he was influenced by Taiga's choice of subject matter and style of

brushwork.3 Thus Suiō painted literati landscapes and plant subjects as well as

Zen figures, adding his own personal charm to the artistic traditions that he

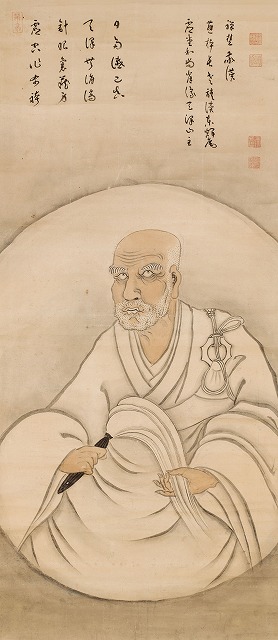

followed. Onc of his most characteristic works is a portrait of Rinzai (Chinese:

Lin-chi), the T'ang dynasty monk from whom the Rinzai sect took its name.

Portrait of Rinzai by Suiō Genro, New Orleans MuseumIn Zen art, Rinzai was usually shown as a fierce master, his hands

clenched in his lap and his face tightened as if he were about to shout "Katsu" at

some unlucky (but ultimately fortunate) pupil. Rinzai was indeed an influen-

tial if unorthodox teacher, famous for shocking his followers into enlighten-

ments beyond the confines of their everyday minds. Many of Rinzais sayings

were renowned: "Understanding and not understanding are both wrong ....

On meeting a Buddha slay the Buddha .... Bring to rest the thoughts of the

ceaselessly seeking mind .... Do you want to know the Patriarch-Buddha?

He is none other than you who stand before me." It was Rinzai who

aswered the kōan "What was the purpose of the Patriarch's coming from the

West?" with the comment "If he had a purpose, he couldn't have saved even

himself."The portrait that Suiō created of this venerated but irascible patriarch is

unexpected; the old Chinese monk leans on his hoe (a reference to his practice

of planting pine trees) and peers over his shoulder as though he were shy and

retiring, an example of ironic humor on the artist's part. Nevertheless, there is

an intensity in the crescent-moon shape of the figure that belies the mildness

of the pose. His eyes, although looking out at us, seem to be staring into his

own head. Suiō emphasized the face of Rinzai by the gray cowl behind his

head and by thickening the line of his shoulder as it reaches his cheek. A

marvelous emptiness is suggested by the large white space outlined by the

robe, while a firm structure for the painting is achieved through the use of

thick gray strokes at the lower part of the robe and the strong outlines of the

feet. The variety of wet and dry gray ink tones in this work shows the

influence of Taiga, but the strength, humor, and charm of the portrait are

characteristic of Suiō.A favorite Zen painting subject has long been the pair of Chinese eccentrics

Kanzan and Jittoku (Chinese: Han-shan and Shih-te). Suiō often depicted

them, pointing to the moon with happy or gleeful faces.

Kanzan and Jittoku, 27.8 x 102.6 cm

Seattle Art Museum

He also followed the Zenga practice of representing figures merely by their attributes.

Jittoku, who was a kitchen sweep at a Chinese mountain temple, would

sometimes carry scraps of food in a bamboo tube to his poet friend Kanzan.

To an audience familiar with Zen, Suiō's depiction of a broom and a bamboo

vessel is immediately recognizable as representing attributes of Kanzan and

Jittoku. Suiō's brushwork is fresh, gentle, and spontaneous. Although

ranging only from light to dark gray, the ink seems to reverberate

gently in its tonal variety, creating a sense of spiritual calm with its misty,

shadowy beauty. The strong composition of the painting, organized in verti-

cals and diagonals, also gives a sense of vibrant movement to the scroll that

belies its simplicity.Suiō's inscriprion says, "This too is Kanzan and Jittoku." Was this merely to

clarify his subject? Or is the artist drawing our attention not only to the play

between figures and their attributes but also to the entire question of what a

painting is? Zenga is nothing more than ink on paper or silk, yet we can feel

the joy of Kanzan, the meditation of Darurna, the intensity of Rinzai, the

humor of Hotei. Sensing the personal character of the artist through his brush-

work adds another level of reality to the painting. The goal of Zenga is com-

munication between artist and viewer, which demands active participation on

both sides. Suiō painted an evocative image, but unless we recreate the pair of

figures in our own minds, it will have no life. When we do, we share the Zen

spirit not only of Kanzan and Jittoku, but also of Suiō.The modest and amicable character of Suiō Genro sometimes led to misun-

derstandings and criticism. He once called upon a Confucian samurai named

Yanada Zeigan (1672-1757). While they were talking, Zeigan's sixteen-year-

old son came in and bowed to his father. Suiō nodded politely to him,

whereupon the young man said, "I have bowed to my father, why should I

bow to a Buddhist monk?" Suiō patted the young man on the back and said he

was a prodigy. Zeigan later criticized Suiō, calling him vulgar in comparison

with Hakuin, who would never flatter anyone. When the monk Myōki of

Kyōkuen-ji heard about this, he said that Zeigan was ignorant and confused by

not understanding that Hakuin was like thunder beating against a mountain

while Suiō was like the soft clouds at its summit. Their "ink traces" bear out

this astute assessment.When the occasion arose, however, Suiō could be as patient and ultirnately

as firm as his teacher. One day a monk from Ryūkyū (Okinawa) came to visit

Suiō for his instruction. Suiō gave him the "one hand clapping" kōan to

meditate upon, and the monk stayed for three years. At the end of that time he

came to Suiō and lamented that he had not yet reached enlightenment and that

he had to return home to show his "same old face." Suiō felt sympathetic and

told him not to worry but to sit in intense zazen for seven days. The monk

followed his advice but returned to report that he had still not reached satori.

Suiō again told him to meditate for seven days, but again the monk failed to

achieve enlightenment. Suiō said that some masters in the past had needed

twenty-one days of zazen therefore he must try once more. The monk did so

but the result was no better. Suiō then told him to meditate for five days. The

monk returned and said, "Again the same; no satori." This time Suiō told

him, "If you cannot reach enlightenment in three days, you will die." The

monk then meditated "to the death," and was finally able to penetrate the "one

hand clapping" kōan. He and Suiō were both elated, and the monk was author-

ized to carry on his master's teachings.Toward the end of Suiō's life, a pupil of Hakuin and Tōrei named Gazan Jitō

(1727-1797) became known as an outstanding Zen teacher. In the summer of

1789, Gazan organized a Zen meeting on the Hekiganroku in Edo at Kishō-in

Although he was in poor health, Suiō decided to attend, despite his followers'

entreaties. On the return to Shōin-ji, he suffered a stroke, and by the end of the

year he was in critical condition. His followers asked for a final poem; at first

he refused, but then he wrote the following verse, closed his eyes, lay on his

side, and died peacefully:I have deceived the Buddha

For seventy-three years;

At the end there remains only this—

What is it? What is it? Katsu!Gazan apparently felt somewhat responsible for Suiō's stroke, and later

inscribed on a portrait of the master the following pair of memorial verses. In

the second poem, he uses the words "floating island," which is one of Suiō's

names.A beacon of light in a dark cavern,

This old monk shines like the blade of a pickax.

The earth receives the sun's blessing,

Never troubled by its appearance and disappearance.

His scolding fist reverberates among his students,

His fiery shout smashes the palace of the devil,

Amidst the vast ocean of suffering,

At the end, there remains only this—Over the billowing waves of the ocean of suffering,

The moon shines on a floating island;

Through a thousand pine trees

Moves the sighing wind.Gazan's poems suggest his reverence for the master's Zen achievements. He

offers a different image of the monk's life than the one we gain of Suiō through

his art, which is gentle and humorous, but inner strength can appear in many

guises. Suiō's breadth of spirit was recognized by all who knew him; it shines

through his ink paintings like the blade of the pickax in Gazan's verse.NOTES

1) One version of the name Suiō means "old drunkard," although he later used another

character instead of "drunkard" that is pronounced the same way. According to legend, this

happened after he was told that his name was not proper for a Zen monk.

2) For example, Suiō invited his old friend Kaigan to lecture at a meeting held for eight

hundred monks and laymen on the seventeenth anni versary of Hakuin's death, and on another

occasion Suiō allowed the visiting monk Jikugen from Sanuki (Shikoku) to write a poem for the

opening lecture at a Hekiganroku meeting at Seiken-ji in Kōtsu.3) There have been various theories about the artistic influences among Taiga, Hakuin, and

Suiō. One suggestion has been that Hakuin was influenced by Taiga, perhaps through the

intermediary of Suiō. The paintings and calligraphy of Hakuin, however, do not bear this out.

Another theory is the reverse, that Hakuin influenced Taiga's art. It is known that Taiga was

deeply impressed upon hearing Hakuin lecture in Kyoto in 1751, and after that time many of

Taiga's works display a new boldness and what might be called a Zen spirit, but there seems to be

no direct influence from Hakuin's brushwork to that of Taiga. That Taiga influenced Suiō,

however, is clear; their friendship is documented by anecdotes of Taiga painting a landscape for

Suiō. Furthermore, Taiga's style of creating variations of tone within a single brush stroke can be

seen in a number of paintings by Suiō.

寒山拾得画賛, 55×125cm

Kanzan Jittoku Zu (Hanshan and Shide)The visible area is filled by a sutra scroll, which is Hanshan's trademark object, hung on a broom—Shide's trademark object. Hanshan's poetry is inscribed on the scroll. Kanzan peers at the scroll from the side, and Jittoku gazes up at it, hands clasped behind him. The inscription praises the virtues of Hanshan's poetry, saying, "I have Hanshan's poetry in my abode/A read that surpasses even the scriptures/It sits atop the folding screen/I contemplate a verse now and again." The depiction of the head of a person looking directly above can be found in the figure paintings of Ikeno Taiga among others.

Zen Monk Bukan,

Hanging scroll, ink on paper

129.3 x 41.9 cm

遂翁元廬 SUIO Genro, 1716–1789, artist

月船禅慧 GESSEN Zenne, 1701–1781, inscriber

※写真は遂翁元盧筆/遂翁元盧画・頑極禅虎賛「南泉一円相図」(禅文化研究所蔵)。

南泉普願 Nanquan Puyuan (748-835)

隻履達磨, Sekiri [One Shoe] Daruma by Suiō Genro

35×102 cm

Daruma by Suiō Genro

Wild Duck Koan (Mazu & Baizhang) by Suiō Genro

LACMA

Portrait of 虚堂智愚 Xutang Zhiyu (1185-1269) [aka 息耕 Xigeng*]

(Rōmaji:) Kidō Chigu [aka Sokkō*]

by Suiō Genro