ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

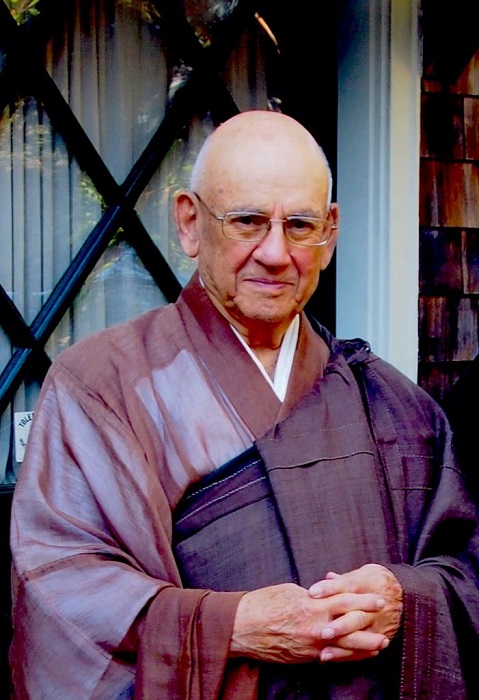

Sojun Mel Weitsman (1929-2021)

Dharma name: 白竜宗純 Hakuryū Sōjun

Sōjun (宗純) Mel Weitsman (born 1929) is a Soto Zen roshi in the lineage of Shogaku Shunryu Suzuki-roshi, a Dharma heir of Suzuki’s son Hoitsu Suzuki.* Sojun-Roshi is founder and guiding teacher of Berkeley Zen Center, which opened its doors in 1967. Suzuki-Roshi had asked Mel to open the zendo for his students in the Berkeley area. Mel began his Zen practice in 1964 at the San Francisco Zen Center (SFZC) and was ordained a priest by Suzuki in 1969. Mel also served as co-abbot of SFZC from 1988 to 1997. Sojun-roshi is an editor of the book Branching Streams Flow in the Darkness: Zen Talks on the Sandokai.

* 鈴木牛岳包一 Suzuki Gyūgaku Hōitsu (1939-) [eldest son of Suzuki Shunryū]

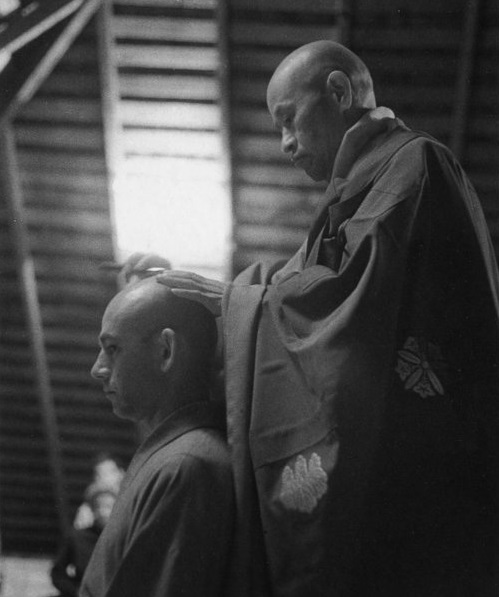

Shunryu Suzuki ordaining Mel Weitsman, 5/19/1969

Sojun Roshi was born in Southern California in 1929. His broad life experience includes years of art study with Clifford Still at the San Francisco Art Institute, abstract expressionist painting, and work as a house painter, boat painter, cab driver, and music instructor.

In 1964 he began to practice at San Francisco Zen Center on Bush Street, and in 1969 was ordained by Suzuki Roshi as resident priest at the Berkeley Zendo. Sojun received Dharma transmission from Suzuki Roshi’s son Gyugaku Hoitsu at Rinso-in Temple in Japan in 1984, and was officially installed as abbot of the Berkeley Zen Center in 1985. He was co-abbot of San Francisco Zen Center from 1988 to 1997. Weitsman Roshi has given Dharma transmission to twenty individuals, and has ordained twenty-three priests.

Along with his responsibilities in Berkeley, Weitsman Roshi continues a long involvement with the San Francisco Zen Center and Tassajara. He lives in North Berkeley with his wife Liz.

Sojun on the development of the Berkeley Zen Center

In 2007 Berkeley Zen Center celebrated its 40th anniversary. For that occasion, Sojun wrote the following:

“It is hard to believe that it has been forty years since we opened the Berkeley Zen Center in that big house at 1670 Dwight way, in February, 1967. We loved that old two-story place, with its steep stairs leading to the large, square, attic, which we converted to a zendo, and the spacious yard, which became a thriving organic garden.

“I had only been practicing with Suzuki Roshi for three years before he asked me to find a place for his students in Berkeley to use as a zendo. Before we had the Dwight Way house, zazen would take place in the various living rooms of his students. He would come over from San Francisco every Monday morning, sit with us, give a talk, and have an informal breakfast. When he became too busy and couldn’t come, his assistants, Katagiri Sensei or Kobun Chino, would come. On weekday mornings, and on Saturdays and sesshin days, his more devoted students would go to Sokoji, his temple in San Francisco, to practice.

“We were at Dwight way for twelve years, during which time we offered to buy the building. I had the feeling that it wasn’t going to work out, so I rode my bike up and down the streets of Berkeley looking for a suitable place. Although it seemed like an almost impossible task, it generated enough interest that one of our members, who knew the owner of two adjacent properties containing four houses at 1929-1933 Russell Street, mentioned our search, and it developed that the owner thought the property would be ideal for our purpose and that he would like to sell to us.

“We knew what we wanted but we had almost no money. That’s when I had the idea of asking each sangha member for $200.00 to get us started. There was an enthusiastic response. Our members contributed low-interest loans and some no-interest loans, and some risky, large, unsecured loans, as well as contributions. When I think about the level of trust within the sangha I find it remarkable. We also had garage sales, flea market sales, and bake sales. Peter Overton was the manager of the Tassajara Bakery on Cole St. in San Francisco at that time. We were able to make brownies there at night, and on the weekends we sold them at park fairs. A number of well-known Bay Area poets did a benefit reading for us. Among them were Phil Whalen, Michael McClure, and Diane di Prima. With some creative financing we were able to make the down payment. And many years later, with the help of some key members, we eventually paid off the mortgage.

“I always envisioned the Berkeley Zen Center as a grassroots endeavor supported by our members; a kind of neighborhood zendo. We have rarely sought outside help to take care of our needs. I felt that the validity of a practice place was attested to by the members’ contribution of their time and resources to mutually support their place, their practice, and each other. I don’t remember a time when we ever had a threatening or serious financial crisis. I think that has been due to my “What me worry?” naïve attitude, counterbalanced by our long line of talented treasurers and sincerely concerned board members.

“The practice at Dwight Way had developed from an acorn into a tree, and had grown naturally into its surroundings. Transplanting this tree into another environment was a different story. We had to make peace with suspicious neighbors who thought we would bring degradation to the neighborhood, awakening everyone in the wee hours to the sound of loud drumming and chanting. There were also angry tenants who did not want to be moved. We had three pre-approval meetings with the board of adjustments and the city council. I think that the city council was impressed that so many respected citizens would testify on our behalf, and we finally received our permit.

“We all loved that Dwight Way Zendo so much. There are many silent, personal dramas that take place in a zendo, and we become attached to that place. I think there is something about the quality of light that appears at certain times of day, together with the profound stillness in a zendo that has something to do with it. I didn’t know how I could leave it. But since the first day at Russell Street, I have rarely given it a second thought.

“Some of our first tenants at Russell Street were Ron Nestor, Bill and Connie Milligan and their daughter Grace, Pat McMahon, and Miriam Queen. A few years later Bill and Connie’s daughter Amanda would be born here, and my wife Liz would be in labor with our son Daniel in the upper flat next door to the zendo while sesshin was in progress. When we moved in, we used what is now the community room as our zendo. With the space taken up by the tatami mats and meal boards, the aisles were reduced to a width of about 16 inches. It was intimate.

“The building that is now our zendo consisted of two apartments. We decided to convert that building into a zendo. But we were told that you are not allowed to use housing for another purpose without replacing it somewhere else. I had contemplated putting another story under the house next to it. We made a plan, submitted that proposal, and it was accepted.

“Our first project was to raise the house and build a new first floor. The movers lifted up the building, put a couple of huge beams under it and some cribbing, and said goodbye. The rest was up to us. When we had the framing up, the movers would come back and lower the building onto the new frame. We were very fortunate to have a number of carpenters and other capable members. Although it is not possible to mention everyone by name, some who stand out are Reed Hamilton who led the building crew, Bill Milligan, the cement work and drainage, the late David Simon, the electrician, and Doug Greiner, who did the plumbing and everything else, (and has never stopped). The upstairs tenants, the Milligans, had to use an extension ladder to access their tipsy dwelling, and Doug spent a bit of time figuring out how he could get the utilities to work up there. We all turned out with picks and shovels and began digging a trench three feet deep in the sticky clay mud for the new foundation. It took about two years to complete the building, the devil being in the details.

“We had a design committee headed by Ron Nestor, and an architect, Ned Forest, with whom we worked out the design for the zendo. After the 1933-1/2 building was more or less completed, we started work on the zendo. We purchased a load of third-grade yellow cedar, had it sliced and tongue-and-grooved, and laid it for the floor, the clear pieces in the center and the knotty ones under the tans. We used the rest on the ceiling. The whole sangha was involved in the demolition and the construction. After six months the job was completed. We sat our first sesshin there on the subfloor in the uncompleted building, before the windows and doors were installed. When everything was finally finished, we put the Buddha on the altar and turned on the lights and offered incense. It was a wonderful feeling.

“Since then there has been a lot of ongoing work: remodeling, earthquake-proofing, painting, maintenance, and repair. Reed’s father said to me that it ‘s not good to run out of work, because when everything is finished, so are you. And Suzuki Roshi said that rather than complete everything ourselves, we should leave something for our descendants to do. Aside from establishing this temple, I think that the fruit of our sincere practice and our good example will be the best offering to our descendants.

“Although there were always a few residents at Dwight Way, Russell Street afforded the possibility of a more expanded and committed residency, which has provided a solid practice base, even though it has had its ups and downs. Although residents have the convenience of living at the center, they also have responsibilities, I have been careful though, not to favor residents over non-residents. It is natural and easier to respond to, and work with those who are close at hand. But I have always made it a point to reach out to those who are not so easily seen for one reason or another, and to include everyone as much as possible.

“From the beginning, I had no ambition other than to make zazen and Dharma available to people, and provide a place where we could all practice together as Suzuki Roshi wished. I sat twice a day. If someone appeared—okay. If no one appeared, that was also okay. But someone has always shown up. My role was to be the caretaker. I made sure that the zendo was open, gave zazen instruction, made people welcome, answered their questions as best I could, made sure that things were taken care of and running smoothly, and I always deferred to Suzuki Roshi as the teacher. I asked people for books to trade at Moe’s, and created the foundation for the library, which was a big help for my own education. I also became attuned to the organic gardening movement while at Dwight Way, collecting grass clippings all over town for compost, and even collecting garbage from the San Francisco Zen Center, which would be brought to me by a student once a week. He would also bring his violin, and we would play violin and recorder duets after composting the garbage. I grew all kinds of vegetables, and made Liz a greenhouse shed where she grew sprouts and sold them to the old Berkeley Co-op. I enjoyed meeting with people informally in the garden. All this was during the student revolt at UC Berkeley. I remember someone running through the yard and leaping over the back fence with a cop in hot pursuit.

“As time went on, my practice matured along with the development of the zendo and my association with Suzuki Roshi. When he passed on I was on my own. I always had the question in my mind of how I would practice when he was gone and felt like I was preparing for that. I still feel his teaching in my bones and his humility stick on my shoulder.

“Suzuki Roshi gave me permission to do whatever I wanted. He observed what I was doing, but never gave me any criticism or told me what to do. Of course, I was following his model or imprint. What I wanted was to establish a practice based on a quasi-monastic model, with the members taking responsibility for everything from coordinator to bathroom cleaner. As needs have arisen, practice positions have evolved, and the rotation of positions has enabled us to interact with and engage the practice in creative and supportive ways. We created an unprecedented lay practice period with no role models, based on the possibilities and circumstances of the participants. Each practice period has had a shuso or head student. Out of this have come our practice leaders. There has also been a succession of head gardeners, each one adding to the ongoing development of the grounds, helping to create a peaceful environment. Serving in positions such as cook and food server to the sangha (and the homeless shelter), zendo manager, work leader, and sesshin director, has produced many experienced, mature members.

“Everyone’s participation is important and there is no position that is not significant. Regardless of the comparative differences of position, when each one of us fulfills our task thoroughly we are all equal, and each one of us is responsible and engaged in turning and being turned by the practice. In that way it feels like the members give to the temple and the temple is a gift to the members.

“Although we established the temple in 1967, the sangha officially invited be to be Abbot in a Mountain Seat Ceremony in 1985, the year after I received Dharma transmission from Suzuki Roshi’s son and Dharma Heir, Hoitsu Suzuki.

“In 1988 I was invited to be co-abbot with Tenshin Reb Anderson at the San Francisco Zen Center. I did that until 1997. When I wasn’t staying at Tassajara, Green Gulch, or the City Center, I did my zazen at Berkeley Zen Center and commuted to City Center or Green Gulch.

“I also had to find time to include my family in my life. In a way, it was like being an itinerant priest. During that time, I was totally supported and encouraged by our sangha at BZC. The practice was well taken care of by the senior members, and I never had to worry about how things were going. The sangha has always been sensitive to and provided for the needs of my family and myself without my ever having to ask for anything. This was a testament to the maturity and dedication of our practice leaders, our board of directors, and our sangha members. I went through our present membership directory and counted twenty-five who had practiced at Dwight way, including some founding members.

“Because I am so immersed in our everyday activity, it seems very ordinary to me, and I can almost take it for granted. But when I step back and observe the quality of practice and the tremendous amount of sincere effort and commitment of so many people over this past forty years, I am moved beyond words, and I sometimes ask myself, how did this all happen? I am grateful to all our members, especially the longtime steady members who continue to convey the essence of our practice in their Bodhi-Field of daily life, through their wisdom, compassion, and presence. This is the most appropriate gift to a teacher.”

PDF: Seeing One Thing Through: The Zen Life and Teachings of Sojun Mel Weitsman

Counterpoint LLC (2023)

佛祖正傳菩薩大戒血脈

Busso shōden bosatsu daikai kechimyaku

The Bloodline of the Buddha’s and Ancestors’ Transmission of the Great Bodhisattva Precepts

永平道元 Dōgen Kigen (1200-1253)

孤雲懐奘 Koun Ejō (1198-1280)

徹通義介 Tettsū Gikai (1219-1309)

螢山紹瑾 Keizan Jōkin (1268-1325)

峨山韶碩 Gasan Jōseki (1275-1366)

太源宗真 Taigen Sōshin (?-1371)

梅山聞本 Baizan Monpon (?-1417)

恕仲天誾 Jochū Tengin (1365-1437)

眞巖道空 Shingan Dōkū (1374-1449)

川僧慧濟 Sensō Esai (?-1475)

以翼長佑 Iyoku Chōyū

無外珪言 Mugai Keigon

然室輿廓 Nenshitsu Yokaku

雪窓鳳積 Sessō Hōseki

臺英是星 Taiei Zeshō

南甫元澤 Nampo Gentaku

象田輿耕 Zōden Yokō

天祐祖寅 Ten'yū Soen

建庵順瑳 Ken'an Junsa

朝國廣寅 Chōkoku Kōen

宣岫呑廣 Senshū Donkō

斧傳元鈯 Fuden Gentotsu

大舜感雄 Daishun Kan'yū

天倫感周 Tenrin Kanshū

利山哲禪 Sessan Tetsuzen

富山舜貴 Fuzan Shunki

實山默印 Jissan Mokuin

湷巖梵龍 Sengan Bonryū

大器敎寛 Daiki Kyōkan

圓成宜鑑 Enjo Gikan

祥雲鳳瑞 Shōun Hōzui

砥山得枉 Shizan Tokuchu

南叟心宗 Nansō Shinshū

觀海得音 Kankai Tokuon

古仙倍道 Kosen Baidō

逆質祖順 Gyakushitsu Sojun (187?-1891)

佛門祖學 Butsumon Sogaku (1858-1933) [Suzuki Shunryū's father; Gyokujun So-on's master]

玉潤祖温 Gyokujun So-on (1877-1934)

祥岳俊隆 Shōgaku Shunryū (1904-1971) [鈴木 Suzuki]

牛岳包一 Gyūgaku Hōitsu (1939-) [鈴木 Suzuki; eldest son of Suzuki Shunryū]

白竜宗純 Hakuryū Sōjun (1929-2021) [Mel Weitsman]

Dharma successors

Zenkei Blanche Hartman, Zoketsu Norman Fischer, Dairyu Michael Wenger, Edward Espe Brown, Hozan Alan Senauke, Steve Weintraub, Myogen Steve Stucky, Ryushin Paul Haller, Josho Pat Phelan, Gil Fronsdal, Fran Tribe, Maylie Scott, Shosan Victoria Austin, Peter Yozen Schneider, Chikudo Lew Richmond, Soshin Teah Strozer, Daijaku Judith Kinst, Shinshu Roberts, Mary Mocine, Myoan Grace Schireson

Zen in America

Sojun Mel Weitsman

In the mid-1960s there were two popularizers of Zen for the American public. From Japan it was D.T. Suzuki, and on the American side was Alan Watts. Watts had a program on radio station KPFA in Berkeley where he gave weekly talks on Zen "philosophy." He also wrote many popular books on the subject. The title of one of his short publications was: Beat Zen,Square Zen, and Zen.

Beat Zen referred to the explorations by the counterculture, the so-called Beat Generation, searching for genuine spiritual disciplines. It was a generation dissatisfied with the materialistic culture and the shallow state of Christianity and Judaism at that time. The poetry of the Beats reflected this desire for spiritual renewal, inspired by the example of the radical independent attitude of the old Chinese Zen Masters. This was the period of the late '50s and the early '60s.

Square Zen referred to the formal practice of Zen monks in a monastic setting supported by centuries of development and history. It was the Zen of discipline and established procedures--Establishment Zen. This is the Zen that was brought to us by Asian teachers in the 1960s. Most people were surprised that such a thing existed, as the impression they had was of a freewheeling Zen with no restrictions. But the arrival of Soto Zen teachers like Shunryu Suzuki ,who established the San Francisco Zen Center, and Taizen Maizumi, of the Los Angeles Zen Center, stirred up a lot of interest.

This interest was shared by a wide spectrum of society including intellectuals, artists and students of all kinds, psychologists, housewives and beatnicks. The teachers introduced the formal practice of zazen (seated cross-legged meditation), which is the heart of practice. Maezumi Roshi also introduced systematic koan study. And along with the practice came Dogen Zenji's teaching.These teachers made a strong effort to introduce Dogen's teaching at a time when there was very little of his work available in translation. So our teachers had to exemplify Dogen's teaching through their own practice. I believe this is one reason they were so effective and inspiring.

It was in this atmosphere that Beat Zen met Square Zen. By the mid-'60s the hippie subculture was replacing the beatnicks. Hippies came to the Zen centers seeking a way out of the drug culture. There was a feeling shared by many that they could give up their drug-induced highs for natural highs induced through meditation. Those who continued in the practice, however, came to realize that zazen is a practice of radical sobriety. By the end of the decade Zen centers were crowded with students, a good many of whom began regularly to cut their hair and wash their clothes and feet. They took on the role of Zen students, sitting zazen at five o'clock every morning, bowing and chanting, and finding a freedom and a depth in their lives that they had never experienced before.

With the arrival of the Japanese teachers Zen became a practice and not merely a philosophy. By the late '60s more teachers were coming from Japan, Korea and Vietnam, including Rinzai teachers. They had different styles but they also had much in common. For instance: They offered the practice to men and women equally, which was a new concept for them. And they opened up a daily zazen practice for lay people, establishing strict practice schedules that included extended meditation retreats (sesshins) which, along with lectures, teisho, and study, created a vital and exemplary way of life open to anyone willing to wholeheartedly devote themselves to it.

It is important to note here that the actual practice of Zen in Japan at that time was at a low ebb, and the teachers who came here, having heard of the interest of many foriegners, hoped that this would be fertile soil in which to plant the seeds of Buddha Dharma. They came on their own,unsponsored by the establishment. Therefore they were free to teach according to their own insights. Most of the teachers understood us very well,and when they came here they devoted themselves to our needs and never looked back. Often they were criticized by their superiors back home who didn't understand what they were doing. Although they offered us the practice that they knew and were familiar with, there was no doubt in their minds that change would be inevitable and encouraged us to be open to change and at the same time to absorb as much as possible of what they had to offer and to proceed slowly so that we would have as firm a foundation as possible.

The raw energy and open attitude of the American Zen students, together with the formal, established, and compassinate practice of the Asian teachers--Beat Zen meets Square Zen--produced "Zen." In 1967 the San Francisco Zen Center established the first American Zen monastery at Tassajara. This was soon followed by the Los Angeles Zen Center's Mountain Center, and the Minnesota Zen Center under Katagiri Roshi.The Cimmeran Zen Center in Los Angeles and Mt. Baldy was founded by Joshu Sasaki Roshi ,a Rinzai Zen teacher,and the Kwan-um Zen school by the Korean teacher Seung-san San-senim.In New York there was Edo Roshi and Sokei-an Sasaki Roshi ,both of the Rinzai school as well as others.

The '70s were a time of dynamic expansion for the Zen Centers. Thousands of students were participating in this American Zen culture. The San Francisco Zen Center developed three major practice places. At one time the Los Angeles Zen Center owned nearly an entire city block filled with students. But the expansion happened too fast and the bubble burst in the mid-'80s due to errors in leadership.

Then came a time of reflection and careful examination. The autocratic leadership gave way to a more democratic restructuring. A lot of attention was given to the equal status of women and men. Our Japanese teachers were surprisingly open to working with women in a way that was not usual in Japan. They felt a certain amount of freedom here to explore new ways and let go of old cultural prejudices. As a consequence women's practice has developed, producing many fine teachers. At present the abbots of both the L.A. and S.F. Zen centers are women.

Another characteristic is the practice of lay people. Our Japanese teachers were a combination of monastics and temple, or family, priests. And we inherited this complex tradition. Suzuki Roshi said "You are not exactly lay people and not exactly monks. I think you are looking for an appropriate way of life." Consequently we have lay people with a daily practice comparable in intensity to that of many ordained people in Asia. In Japan it is customary for young men to have ordination and then enter a training monastery. But in America the students train for at least five years and up to more than twenty years before being ordained as priests. Dharma transmission is usually given after ten or fifteen years although not automatically. There is an effort to do this carefully and selectively. By the early '90s there were students who had been practicing twenty or thirty years who were receiving Dharma transmission and leaving the large Zen centers to be resident priests and teachers at smaller temples. The smaller temples are almost entirely composed of lay members who sit zazen as their schedules and responsibilities allow. When a sitting group is large enough to support or at least partially support a teacher, it can invite someone or ask the larger Zen center to recommend or send someone.

There is a strong movement in American Buddhism to take part in social action regarding the environment, equal rights, racial equality, social justice, the legitimacy and rights of gay people, and the peace movement. There are also teachers and students providing meals for the homeless and guiding meditation groups in the prisons. Another uniquely American development has been the role played by the San Francisco Z.C., among other Zen centers, in the health food movement of the past thirty years. Vegetarianism has become the preferred way of eating for millions of Americans largely through the publication of best-selling vegetarian cook books.

Nevertheless, I believe that the most important contribution that Soto Zen can offer is making available to people the practice of zazen. There are many social and charitable institutions in America that help people. But zazen--in both its narrow sense of sitting in emptiness in the middle of delusion and enlightenment, and in its broad sense of living a life free from suffering within suffering--is our most valuable gift to Americans. Zazen is the heart of the practice that Master Dogen brought home from China some 800 years ago. Sitting still with straight posture, letting mind follow breath, one lets go of all discriminative thinking--good or bad, like or dislike, pleasure or displeasure, grasping or aversion. With no thought of gain or loss one settles into the heart of pure existence with all beings. Zazen is our great teacher. It is the practice that levels all things and cannot be fooled by the cleverest mind. It always shows you exactly where you are and demands your utmost sincerety and total presence. As the great sage Shakyamuni said, "Come and see for yourself."

To sum up to this point, Soto Zen in America, rooted in the teaching and inspiration of Master Dogen, is slowly but surely finding its own direction. For example, the San Francisco Z.C. has not had a Japanese teacher since 1971 and has had to depend on its own resources Surmounting crises and normal growing pains, S.F.Z.C., in common with other Zen centers, is at present vital and flourishing.

Now I would like to say something about the practice of Soto Zen in America. The larger centers like the S.F.Z.C.and its components--the monastery at Tassajara and the farm at Green Gulch--are residential centers which are open to nonresidents as well. At Tassajara, staff conducts two 90-day angos, or practice periods, each year for the students, and devotes the summer months to the guest season, which in turn provides financial support for the students. Because American Zen does not operate within a Buddhist culture we must devise ways to support the practice. Green Gulch Farm, more accessible than Tassajara to the public, conducts practice periods and operates an organic farm as its centerpiece to support the practice. When driving down the road one can see the cultivated fields stretching to the ocean There is a lecture Sunday mornings that is attended by several hundred people. There are also classes offered in all aspects of Buddhist studies. In addition, G.G. serves as a conference center for private and public groups.

A resident student's day typically starts with zazen between 4 and 6 AM, depending on the time of year and the present circumstances, followed by a service composed of bowing and chanting Then comes a formal breakfast sitting cross- legged in the zendo, a period of cleaning, a break, an hour of study, zazen until noon or a lecture, then lunch in or out of the zendo and a break. The afternoon is usually devoted to work. The evening after dinner might include a class or independent study ending with zazen around 9 o'clock. The students also have private interviews with the teachers, called dokusan.

This schedule, with variations, is to be found in practice places all over the country. Periodically, sesshin is held. Sesshin is an intensive retreat of from one to seven days of zazen starting anywhere from 3 to 5 AM and ending anywhere from 9:30 in the evening to midnight. Typically, sesshin consists of 40 minutes to an hour of zazen followed by10 or 15 minutes of walking meditation, called kinhin. Meals are eaten formally, while sitting in the zazen posture on the zazen cushion. Sometimes there is a work period. Silence is maintained. All the cooking is done by the students and is considered a high form of practice.

There are also smaller nonresidential centers or those with a small number of residents whose members are mostly working people such as professionals, students and the like. The more established smaller centers might offer zazen in the early morning and also in the late afternoon or evening as well as a weekend program and sesshins. These centers are usually supported by the members and may or may not support a priest. Some of the smaller centers may offer zazen only once or twice a week. In the residential centers the students are committed to following the daily schedule as long as they are residents. It is not uncommon for the residents to be employed outside the center. In the nonresidential temples, in contrast, the members must find their own level of participation, depending on their personal responsibilities to work, family, and other obligations.

Some Soto Zen teachers and most Rinzai teachers emphasize systematic koan study. Students may have to pass as many as 200 koans. Often the first koan is as follows. A monk asked Master Joshu, "Does a dog have Buddha nature?" Joshu answered "Wu" or "Mu,"which means "No." What is the meaning of "Mu"? That is the koan the student must work on. During dokusan the student must face the teacher and try to answer the koan. It may take a long time before an answer is found. In koan study the student might be encouraged to work on the koan during zazen. But for most Soto Zen students, shikantaza, just sitting, is more usual. Some Soto Zen teachers don't take up koan study at all, preferring shikantaza solely. Others teach shikantaza and also use koans in an unsystematic way. Many teachers feel that if the koan occupies the mind during zazen, then that zazen becomes the servant of the koan, and shikantaza looses its relevance as the central focus of zazen. Both traditions have produced good teachers. Some students are more tempermentally inclined toward koan study while others tend toward shikantaza. Those who practice in one or another of the two traditions are for the most part respectful and uncritical of each other.

One of the difficult areas is the inclusion of a workable family practice. Because of the strong emphasis on zazen, which is each person's practice, there is little attention paid to those who are not directly involved. And in this day and age, with everyone so busy, it's hard to find the time to devote to a social program as well. In Japan the temples are much more family oriented. This is largely due to the fact thatrin the 17th century, Tokugawa shogunate forced all Japanese people to register with the temples and those temple affiliation persist to this day, and in the Meiji Period, in the second half of 19th century, Japanese government allowed Buddhist priests to have family. This has created a family priest caste that operates the temples somewhat like a western-style church--at the expense of zazen practice, for the most part.

In America, on the other hand, there is no prevailing Buddhist culture, and all the practitioners participate out of their own interest. So zazen and practice flourish at the expense of a social family practice. I have to mention that Maezumi Roshi tried incorporating a family practice based on some of the elements familiar to him such as: Family memorial services at cemeteries, family days at the temple, and home services on various occasions.

All in all, however, Japanese family practice has not taken hold in America. At the same time, it is something that cannot be ignored. It is part of the ongoing development of the American sangha. In addressing this question, many teachers stress the fact that if one is a family member, then the family situation is a field for practice. It is an ideal place to practice the precepts and to set an example. It's one thing to talk about Zen as if you know something and another thing to exemplify your understanding. My observation is that the children of Zen students are not interested in the practice and are often critical. But when the reach the age of 19 or so, they seem to develop an interest and many take up the practice.

It is important to realize that zazen is not a child's thing. At the same time, there is some effort to educate the children about Buddhism and even to introduce them to zazen a little bit at a time. Still, each person must come to it out of her or his own desire. So we are very careful to introduce, but not to force or coerce, nor to expect anything or be attached to the results of our effort. Two characteristics of a mature practitioner are patience and tolerance. A good teacher will work with a student for a long time, being strict and unyielding when necessary and soft and granting at other times, guiding and at the same time allowing the students to find the way by themselves.

Dogen Zenji expressed the meaning of practice/enlightenment in his fascicle Genjo Koan. There he said :

To study the Buddha way is to study the self.

To study the self is to forget the self.

To forget the self is to be enlightened by the ten thousand dharmas.

To be enlightened by the ten thousand dharmas is to free one's body and mind and those of others.

No trace of enlightenment remains,and this no-trace continues endlessly.

In practical terms Genjo means manifesting in the present. Koan means first principal. Genjo Koan means the various activities we do as our practice is extended from zazen. It is the oneness of everyday life and practice as attained through pure practice.

With this understanding, all aspects of daily life are included as practice Therefore both priest practice and lay practice as well as resident practice and practice while lliving at home are possible. This includes both work and family as practice. If you are a Zen student, wherever you go the zendo extends to that place, and right there is where you find your practice.

What is the future of Zen in America? Although Zen seems radical because of its image as a hard or strict practice, compared to other American Buddhist groups it is quite conservative. Some people think that the practice is too ritualistic and are eager to do things in a less formal way. Others like the formality. I think that without being in a hurry to change,we should allow Beat Zen and Square Zen to continue to work together like twining vines with faith that a pure Zen will be the result. As my old teacher Suzuki Roshi used to say: "When you are you, Zen is Zen."

Umbrella Man

Students and friends of Zen teacher Mel Weitsman honor him on his 80th birthday.

By Tricycle Winter 2010

For decades, Sojun Mel Weitsman has been an anchor of the Buddhist community in the San Francisco Bay Area and beyond. It might well be, however, that even if you've been around the North American Buddhist world for many years, you know little or nothing about him. I'm pretty sure that Mel—or Sojun Roshi, as he's called formally as a Zen teacher— is just fine with that.

The image of an anchor speaks of Mel's style of dharma activity: it runs deep and steady, mostly below the surface of things, and its effects are often hard to see. This makes him less than a ready fit for Buddhist publications. His dharma talks, divorced from the quiet force of his presence, can lose much in translation to the printed page. He is not big on innovation, and he doesn't go in for major projects or dramatic pronouncements. If he does attend a conference or seminar, chances are he is in the audience rather than on the podium. He is neither a mover nor a shaker.

What Mel does is pretty much what he has done for more than forty years. In the morning, he gets up early and goes to the zendo (meditation hall) for zazen (sitting meditation) and morning service. He takes care of the Berkeley Zen Center, and he encourages his students. He spends time with his family. At night, he goes to the zendo for zazen and evening service. There's not much there that's newsworthy. Yet, if one investigates the matter further, it is clear that there is much more to the story.

For several years, we at Tricycle have tried to think of something we could do about Mel that would do him justice. Nothing we came up with seemed quite right. Then, last year, I received a copy of a small, privately printed book written for Mel on the occasion of his 80th birthday. The book, Umbrella Man , is a collection of tributes from Mel's 20 deshi , or dharma heirs. Edited by Max Erdstein and Michael Wenger, it is an informal little gem of a book, not least because it so clearly demonstrates that as a teacher, Mel is best appreciated for the light that he has sparked in others.

Mel began Zen practice in 1964 with Shunryu Suzuki, the founder of the San Francisco Zen Center and Tassajara Zen Mountain Center and the author of the now classic Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind . In 1967, Suzuki Roshi, with Mel's help, established the Berkeley Zen Center, and two years later Mel was ordained as the center's resident priest.

After Suzuki Roshi's death, in 1971, the abbotship of San Francisco's City Center and Tassajara passed to his dharma heir Richard Baker, and in 1972 a third temple, Green Gulch Farm Zen Center, was added to the rapidly growing SFZC community. Under Baker Roshi's creative direction, the San Francisco Zen Center became a dynamic hub of Buddhist activity in the West. Across the Bay, at the Berkeley Zen Center, things proceeded at a more modest pace. But Mel was in the zendo every day, even if no one else was, and little by little the membership grew.

In 1979, the Berkeley Zen Center moved from its original location, on Dwight Way, to its present location, on Russell Street. Mel received dharma transmission from Hoitsu Suzuki, Shunryu Suzuki's son and dharma heir, in 1984, and was officially installed as the Berkeley Zen Center's abbot a year later. The zendo on Dwight Way was in the attic of Mel's house, but at Russell Street, the members constructed a beautiful zendo building and housing for a small resident community. Today, the center has more than 150 general members.

In the mid-1980s, the San Francisco Zen Center community went through a long period of upheaval, at the core of which lay questions about leadership and power. This was initiated by events that many felt were part of a pattern on Baker Roshi's part of misusing authority, and eventually Baker Roshi resigned as abbot. In 1988, during what was still a painful and confusing time, Mel was asked to assume the role of co-abbot of SFZC, and he agreed. For the next nine years, while continuing to lead the Berkeley center, Mel stepped up to help guide the San Francisco community. And when it was time to step down, he just stepped down.

In his introductory remarks to Umbrella Man, Hoitsu Roshi writes:

In Japan, we have a custom that celebrates when a person lives for eighty years. We call this Sanju . The “san” of Sanju means “umbrella.” We use umbrella in this case because the character for “eight” resembles an umbrella. When one reaches eighty, his character becomes more generous and broad-minded. His presence becomes like an umbrella, which can protect the people of the world from the rain and wind, the sufferings that arise in life.The Buddha taught that “all constructed things are impermanent” and based his dharma teaching on this. “Impermanence” means that our bodies and minds, together with all things, will diminish and disappear. At the same time, it is precisely because of the impermanence that we grow and mature as years pass by. To grow old is to keep tasting life anew and to gaze at new scenery. It is to understand things that we didn't understand before and to see things that we didn't see until now.

I offer my heartfelt congratulations to Sojun Roshi as he celebrates Sanju . I really hope he will continue to be more and more healthy, that many disciples and Zen students will gather under his big umbrella, and that practicing together they will pass on the essence of Zen.

We at Tricycle join Hoitsu Roshi and the other contributors below in offering our congratulations to Sojun Roshi, the Umbrella Man.

—Andrew Cooper, Tricycle editor-at-large

Shosan Victoria Austin

I first met Mel at the Berkeley Zen Center, when I went there at the invitation of a friend. It was the mid-1970s, and I was looking for support for my Zen practice. Though the zendo was just a collection of sitting places around the edges of an attic room, the floor, the zafus, and the zabutons glowed with cleanliness. It felt cared for—welcoming—and intimate. After several visits, I came to meet Mel in dokusan [a formal, private interview with a Zen teacher]. In response to my question about practice, he said, “Just rely on zazen.” After that, Mel and I would meet for dokusan every so often. I began to notice that whenever I would go on and on, he would fall asleep. Often in the middle of presenting an emotional reaction to something that had happened, I would gradually notice him nodding. Sometimes he would open his eyes very wide, to try to stay with me. When the tone of my voice became authentic and fresh, he would completely wake up. Just last month in dokusan, more than thirty years after our first meeting, he told me, “Just rely on zazen.”

Ryokan Steve Weintraub

I was in the inner circle around Richard Baker at the San Francisco Zen Center, treasurer for five years and president for some years after that. It's a little sad for me now, but during those years, I would say there was an unspoken disdain for this guy Mel Weitsman over in Berkeley. It was like, “We're doing the real thing, this is where the real Zen is. The Zen capital of the universe is here . He's doing something over there , and whatever it is, it's not worth much.” I don't remember anyone ever saying those exact words, but it's quite clear to me that that was the attitude. I'm writing it now with some degree of embarrassment. To not recognize a jewel, it was just arrogance. It was the arrogance of much of SFZC's leadership, including myself at the time. To be proper about it, I shouldn't ascribe that arrogance to anyone else, but I can say that it was certainly my feeling. And I don't think my feeling was unusual.I really didn't have very much to do with Mel during those years. Then, 4 or 5 months after everything blew up in 1983, my wife, Linda Ruth Cutts, and I went down to Tassajara, where we lived for a year and a half. Being at Tassajara really saved my practice life, because it reminded me of Suzuki Roshi's way. For years I had grown increasingly discouraged with myself and, after the crisis, with Zen Center itself, which had been the focus of my life for 15 years. Returning to Tassajara renewed my inspiration.

I recall Mel coming down during that time. He was very warm and supportive to me, though he had no reason to be. I had harbored a haughty attitude toward him previously, but he didn't hold it against me. Sometime during the following years, the idea for the two of us to study together came up, though I don't remember who suggested it. Eventually Mel suggested we begin to study certain writings of Dogen that are generally related to dharma transmission, and I accepted his suggestion. This was tremendously generous of Mel. He didn't have to offer his support in this way; he didn't have to offer dharma transmission. He saw that it would be helpful to me, and that was enough.

Mel is steadfast. There is nothing fancy about him. When “big things” were happening at the San Francisco Zen Center, Mel followed his way, followed Suzuki Roshi's way, teaching and practicing steadfastly, and modestly, at the Berkeley Zen Center. Once, Suzuki Roshi was giving a dharma talk and at a certain point, toward the end, he said, “This is a really good dharma talk. I should listen to this dharma talk.” I believe there is an important line of continuity, steadfast and modest, from Suzuki Roshi to Mel.

I'm tempted to say I don't remember anything that Mel has ever said about dharma. That's an exaggeration. But the point is that the core of the teaching I have received from him has come through how he is—how he is when he walks out the gate of the Berkeley Zen Center, how he is when he talks to me or talks to someone else. Sometimes, though, he'll say something that really hits home. One time, at the beginning of one of our meetings, he asked how I was doing and I said, “Pretty wobbly.” He said, “Oh, you're a wobbly buddha.” The Soto Zen way is not about achieving a particular state or experience; it's about realizing and actualizing Buddha, including wobbly Buddha.

In Genjokoan , Dogen writes, “Those who have great realization of delusion are buddhas.” The place where you get to be Buddha, so to speak, is in delusion, and there's plenty of that to go around. You get up where you fall down. You don't get up somewhere else. It's where you fall down that you establish your practice. Back years ago, at Tassajara, when I was feeling discouraged and confused, Mel helped me by being supportive and open and friendly. He assisted me in getting up where I fell down.

Jusan Edward Brown

Mel surprises me. The surprises are not unpleasant character traits haphazardly revealed or social gaffes carelessly displayed. No, instead, suddenly, in the midst of apparent plainness, sparkle flashes, and the brilliance is reflected in others. I find myself wondering, Where did that come from? Mel isn't doing anything, yet others in the room are flourishing.More than anyone else, I see Suzuki Roshi in Mel's face. I tried for several years to be Suzuki Roshi: “It's okay that you died,” I thought, “you can have my life.” But I just ended up abandoning myself. Mel is just Mel, and there's Suzuki Roshi.

Mel surprises me. The miso soup he serves me looks so plain, and it's so delicious. Calligraphy appears on the back of a rakusu [an abbreviated version of Buddha's robe, given to students at jukai , the ceremony of receiving the precepts]—it's beautiful like the magic of raindrops falling nowhere else. We've worked together with rocks at Tassajara and on Suzuki Roshi's talks for the book Not Always So . It's collaborative—my gifts rise to the occasion in his presence.

Daijaku Judith Kinst

Once I heard a lecture that described the ocean and its layers. The speaker told of the benthic layer, the deepest layer that is not affected by surface characteristics or more superficial tides. I immediately thought of my relationship to Mel. Ours is a con connection in the benthic layer. I think perhaps this is always true between teacher and disciple.riend of mine, a teacher in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, told me how her teacher understood her so well that he knew exactly what she needed, and when, as she developed. She wondered, was that true for me with Mel? I surprised myself when I said no, that in fact we had times of real struggle. But what I remembered, in that moment, was the clear sense that in the stillness of the benthic layer there was an unshakable connection that nourished my growth in the dharma. That kind of connection is exactly what I needed.

While I was his anja (personal attendant) at Tassajara, I had the closest daily contact with Mel and his teaching. Being anja for anyone was not my idea of what I wanted to do with my practice when I went to Tassajara. And it was, perhaps, the greatest gift of my time there. Learning the practice of mutually respectful service and absorbing embodied teaching silently broke down my ideas of who I thought I was and what I thought practice was and allowed a different understanding to form itself. Recovering from cancer treatment, thrown into a darkness I didn't understand, the daily practice of zazen and ordinary contact with my teacher was the best medicine I could have had.

Once, on the way back to Mel's cabin after a meeting, I was complaining about something. He turned to me and said, “You are being a spoiled brat.” Like a cold bucket of water. I knew he was right. In a way I had not seen before, I was circling around my own suffering. There was also kindness when I needed it, but kindness that was respectful of my commitment to the dharma. This was caring that was not confused with sentimentality. This was medicine that went directly to the root.

Dairyu Michael Wenger

I didn't know Mel very well in 1988, when he was asked to be co-abbot of Zen Center. His primary practice place was to be City Center, while Reb Anderson would be at Green Gulch, and the two of them would alternate at Tassajara. The question of religious leadership was consuming the Zen Center community at the time. I watched Mel closely, and he welcomed the scrutiny. He seemed to accept whatever came his way. Soon I realized that I had a new teacher. I found that I could be straightforward with him and that we could disagree without jeopardizing our relationship.Later, he helped me think through my questions about priest ordination. After an initial desire to be ordained, I didn't see any reason to do it. I felt that my being a senior layperson made me more approachable to many students. I felt I understood this.

I grew up with little religious training. My parents were particularly suspicious of religious institutions. I was also very aware of how easy it is for the more narcissistic members of a community to gravitate toward leadership and for those with low self-esteem to defer to them. Mel suggested that I ordain and become the priest I wanted to become, not one that I was critical of. Whatever good reasons I had, I was resisting ordination, thinking that as a layperson I was better than the priests. But no form of practice is inherently superior to another. What a relief it was it was to stop resisting what I really wanted in my heart and let go of such arrogance!

Zoketsu Norman Fischer

It seems to me that the main characteristic of Suzuki Roshi's teaching, and of Soto Zen, is faith in the practice and a steadiness and endurance to keep going with the practice no matter what. As Dogen taught so profoundly, the practice is the enlightenment. There is no enlightenment outside of practice. In the early days (and I know it is the same now) it was clear without anyone ever needing to say so that this was the value most encouraged by Mel. There was sitting every morning at 5 a.m., and Mel was there every day, always on time. Whether there was one person or two or three joining him (and there were seldom more than three or four) he was always there, sitting in his place at the head of the stairs, so that when you walked up the steep stairs to the attic you would see him first, just there, always there. Motionless and quiet. Dwight Way was a pretty busy street and there was sometimes traffic by the end of the morning session, but traffic or no traffic, whatever was going on, there was steady silent sitting. Every day, week after week, month after month. And by now, decade after decade. Though the location has changed and the years have sped by, I am guessing that the practice remains the same and the spirit remains the same: just to do the practice, to have faith in the practice, come what may. To be steady and to endure. To appreciate what is.Not saying much, not explaining much—this was how it was in those days. There were no sesshins, no dokusan. Nothing special or spectacular. Mel gave, I think, a talk at the all-day sittings and maybe there was a weekly dharma talk, but these events were always themselves very quiet. Just part of the schedule. I always found them moving and encouraging, but they were not charismatic or complicated or exciting. Mel would speak pretty simply about our practice, very often bringing up sayings of the old Zen teachers or Dogen. I can't really remember now much of what Mel said, but the general impression I had was of steadiness and wisdom and beauty. Conviction, but lightly held.

Chikudo Lewis Richmond Sojun

Mel Weitsman was my first teacher. I learned how to sit from Sojun; I first met Suzuki Roshi in the living room of Sojun's house. Sojun said to me once, “Everything I have learned has been through patience.” As a generally impatient person, I took this as a great teaching and have never forgotten it; I also think he was just telling the truth about himself.During a period when I imagined I had given up on being a priest, I came to Berkeley Zen Center for a ceremony and watched Sojun bow. That moment turned me; I saw in that bow something that awakened in me a path I thought I had forgotten. Within a few months, Sojun and I were doing transmission together.

After my transmission, I said to Sojun, “Remember, I'm not going to start a Zen group. That's not what I do.” He didn't say anything.

A few years later, after I had started a Zen group and it was thriving, I was again talking with Sojun and reminded him, with a little embarrassment, of my earlier comment. “I guess you must have known something back then that I didn't,” I said.

He replied, “Oh, I don't listen to what people say.”

Right.

What he meant was, “I don't listen to what people say; I listen to what people say.”

Hoitsu Suzuki Roshi

Magnetic teachers who are good leaders tend to have a surprising, unpredictable quality about them. Sojun Roshi is like this. He has a side that is completely unlike a Zen master, and he also has a side that is like a Zen master. It can be said that he has an unpredictable nature.As I see it, the side of him that is completely unlike a Zen master is the one filled with a very folksy, common humanity. He seems like an ordinary, amiable person and not a figure of authority as a Zen priest and teacher. In this way, I think he closely resembles his late teacher, Shunryu Suzuki Roshi. Like his teacher, Sojun is also a very natural person.

Nevertheless, once Sojun takes his seat in the zendo, sitting zazen facing in toward the room, his appearance completely changes and he has the dignity of Great Master Bodhidharma. His piercing gaze glares for an instant and is very penetrating. This is something that his disciples surely know well.

Zenki Mary Mocine

When I spoke to Sojun Roshi during my Mountain Seat [abbot installation] ceremony, I paraphrased King Lear's upright daughter, Cordelia. I told him that I love him like potatoes love salt. I do.