ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

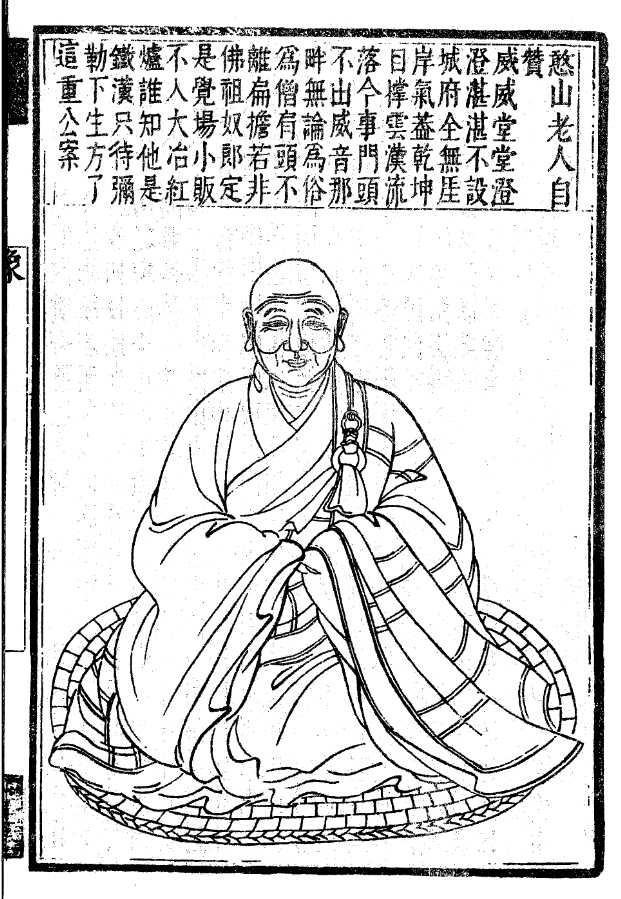

憨山德清 Hanshan Deqing (1546-1623)

(Rōmaji:) Kanzan Tokusei

Tartalom |

Contents |

A gyakorlás és a megvilágosodás lényegi pontjai kezdőknek Tisztítsd meg tudatodat Vers a tudat szemléléséről |

PDF: The Autobiography and Maxims of Han Shan PDF: Practical Buddhism

PDF: A Straight Talk on the Heart Sutra by Ch'an Master Han Shan PDF: The Surangama Sutra Poems Essentials of Practice and Enlightenment for Beginners Han Shan's Looking at the Mind Contemplating Mind Instructions in the Critical Essentials of Cultivating Dhyana Meditation Maxims of Master Han Shan Mountain Living: Twenty Poems Excerpts from Master Han-Shan's Dream Roamings

Challenging the Reigning Emperor for Success: Hanshan Deqing and Late Ming Court Politics PDF: Meditative Pluralism in Hanshan Deqing PDF: The Heterodox Buddhist Poetics of Hanshan Deqing

|

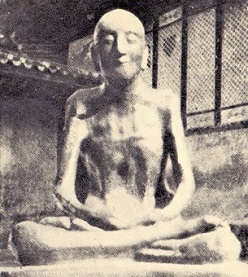

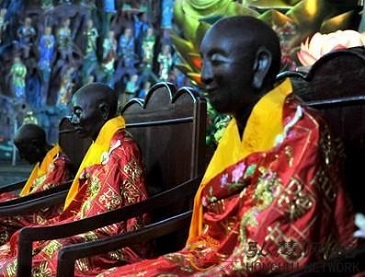

Photos of the body of Master Hanshan at 南華寺 Nanhua Monastery (曹溪 Caoxi, near 韶关 Shaoguan, Guangdong Province)

taken prior to Red Guards smashing it with their rifles (1), and today, restored (2, 3),

on the left side of

the

Sixth Patriarch

Huineng's

lacquered mummy.

Four Eminent Monks of the Wanli Era (Wanli si gaoseng 萬曆四高僧)

Hanshan Deqing 憨山德清 (1546–1623)

Daguan Zhenke 達觀真可 (1543–1603), aka 紫栢真可 Zibo Zhenke

Yunqi Zhuhong 雲棲株宏 (1535–1615), aka 蓮池祩宏 Lianchi Zhuhong

Ouyi Zhixu 蕅益智旭 (1599–1655)

A Buddhist Leader in Ming China: The Life and Thought of Han-shan Te-ch'ing

By Sung-peng Hsü [徐頌鵬 Xú Sòngpéng, 1938-]

University Park and London: The Pennsylvania State University Press

(Published in cooperation with the Institute for Advanced Studies of World Religions),

1979. xvii, 221 pp. Notes, Bibliography, Chinese and Japanese Words, Index.

A Buddhist Leader in Ming China consists of four chapters. In Chapter 1 the sources and methodology are discussed. Chapter 2 concerns the background of Han-shan Te-ch'ing's life and thought. Chapter 3 presents a detailed account of Han-shan's life, based almost entirely on his autobiography. The last chapter discusses his teachings and his views about the Mind, the Universe, Man, Evil, and the Path to Salvation.

PDF: Book review by Chün-fang Yü

In: Ming Studies, 1986:1, 59-64.

Han-Shan Te-Ch’ing: A Buddhist Interpretation of Taoism

By Sung-peng Hsu

Published in Journal of Chinese Philosophy 2 (1975) 417-427

http://www.worldreligionsjourney.com/buddhism/buddhist-interpretation-of.pdf

Poems

by Hanshan Deqing

IN: Clouds Thick, Whereabouts Unknown: Poems by Zen Monks of China

Translated by Charles Egan

(Translations from the Asian Classics), Columbia University Press.

Hanshan Deqing (1546–1623), zi Chengyin, was from Quanjiao (in Anhui); his secular surname was Cai. He was the most important figure in late Ming Buddhism and was famous as a preacher, writer, and political insider. The young Deqing gained an interest in Buddhism from his mother, and entered Bao'en Temple in Jinling (Nanjing, Jiangsu) at age eleven, over the objections of his father. After training in a mixture of Chan and Pure Land teachings, in the early 1570s he began a period of travel. He settled for a time in a hut at Longmen, near the northern summit of the sacred Mount Wutai (at Wutai, Shanxi). As he relates in his autobiography, as spring arrived he was distracted by the sound of the thundering torrents, “like ten thousand galloping horses.” He chose a footbridge near a stream and meditated there every day, until one day he suddenly forgot his body and the sound disappeared. In 1577 he received the patronage of the empress dowager, a devout Buddhist. By 1582 his lectures on the Flower Garland Sūtra drew ten thousand people daily; he had earlier laboriously written out the sūtra in his own blood, in honor of his parents. In 1583 he moved to a new retreat on Mount Lao (in Jimo, Shandong). The empress dowager soon donated money to build Haiyin Temple nearby, and arranged the gift of a complete Buddhist canon. He was drawn into court politics and became embroiled in the controversy over choosing the heir-apparent. In 1595 he was denounced and imprisoned, then defrocked and dispatched to serve as a soldier at Leizhou (in Guangdong). This was only a temporary setback, as his admirers included many of the leading literati and officials of the day. Although not formally reinstated as a monk until 1605, Deqing was able to continue his religious work almost uninterrupted. In 1601 he began to rebuild the temple complex at Caoqi (in Qujiang, Guangdong), once home to the Sixth Patriarch; this work would consume him for ten years. He returned to Caoqi in 1622 and died there a year later. “The water in Cao Stream suddenly dried up, all the birds cried mournfully, and by night there was a light that illuminated heaven.” His “flesh-body” (mummy) was kept at the temple as an object of reverence, and is still there today.

SENDING OFF CHAN MONK GAO BACK TO CIHUA

A leaf boat floats

on an endless sea;

Misty waters vast and vague,

the ford is hard to find.

Go back to your mountain,

fulfill your life’s goal;

A secluded place of flowers

where birds call the spring.

LIVING IN THE MOUNTAINS

Clouds break over the land, spring light stirs;

A faint scent of plum blossom, whence does it come?

I lean on my staff to look for the secret valley,

While one branch hangs low over the eastern wall.

NIGHT DEPARTURE ON LING RIVER

As wild water twists and turns,

An empty boat floats where it will.

Watching the moon, the color brightens;

Hearing the river, the sound slowly stills.

Floating clouds are beyond my body;

White hair frames my mirrored face.

Don’t say I’ve tarried too long:

Ahead lies my old mountain place.

LIVING IN THE MOUNTAINS

My hut is no bigger than a ladle,

But within, I do as I please.

Colored clouds

rise from doors and casements;

The moon and stars

are suspended on the porch.

Thoughts end:

my mind becomes tranquil;

Dust dissolves:

the world is just thus.

The southern wind reaches my sitting mat,

Rustling through six empty windows.

SITTING AT NIGHT, ENJOYING THE COOL

I love the colors of a clearing night,

And in autumn, the birth of the bracing air.

Leaves in the wood

heavy after rain;

Clouds on the peak

light in the wind.

In quiet contemplation,

I see there is no me;

Through strict practice,

I've tired of having a name.

I sit and watch the moon in emptiness,

Intently facing the solitary light.

Han Shan's Looking at the Mind

By Zenmaster Han-shan De-qing (1546–1623)

Tr. by Hakuun Barnhard

http://www.unsui.eu/?page_id=354

Cf. http://www.unsui.eu/?p=352

Look at what your body is – it is not you

But an image in the mirror of awareness,

Just like the reflection of the moon on the water.Look at what your mind is – it is not

The thoughts and feelings that appear within it

But the bright knowing space that holds them.When not a single thought arises, your mind is

Open, perceptive, serene and luminous;

It is complete as great all-embracing space

And holds all kinds of wondrous aspects.Your mind does not come or go away,

Has no particular shape, nor a special way of being.

But a great many beneficial qualities

Come all forth from this one knowing being.It does not depend on material existence,

Material existence covers it up!

Do (therefore) not take vain hopes seriously,

Vain hopes lead to illusory phenomena.Closely investigate this mind, which is

A knowing emptiness, not containing a thing.

When you are suddenly flooded with emotions

Your vision gets unclear, your experience confused.Then at once bring back your presence of mind

And gather all your strengths to reflect.

The clouds will disperse and the sky will clear:

The sun of awareness spreads brightly its light.If no feelings or thoughts arise within

No (worrying) circumstance is found without.

So where lies the original reality,

Of all that has characteristics?If you can be aware of a thought as it arises

This awareness dissolves the thought at once.

Sweep away whatever state of mind may come,

Be present and aware – and you will be free.Good and evil, internal or external,

Transform when you turn towards the heart of it.

Worldly and spiritual forms

Come into being through what you think.Using a mantra and looking at your mind

Are means to polish the mirror of awareness;

Once the obscurations have been removed

They have no more use and can be dropped.All great and deep spiritual abilities

Are already complete within your mind

And you can roam as you wish

To the Pure Land or Heavenly Palace.There is no need to seek the Truth

As your mind is from the start already enlightened.

When ripe, all things are fresh and new

When fresh and new, they are inherently already ripe.Day and night all things are wondrous

And you will have faith in whatever you meet.

The above is what you need to know

Regarding the mind.

Contemplating Mind

By Han Shan Te-ch'ing (1546-1623)

Translated by

Sheng Yen with Commentaries

In: Getting The Buddha Mind

Look upon the body as unreal,

An image in a mirror,

Or the reflection of the moon in water.

Contemplate the mind as formless,

Yet bright and pure.

Not a single thought arising,

Empty, yet perceptive,

Still, yet illuminating,

Complete like the Great Emptiness,

Containing all that is wonderful.

Neither going out nor coming in,

Without appearance or characteristics,

Countless skillful means

Arise out of one mind.

Independent of material existence,

Which is ever an obstruction,

Do not cling to deluded thoughts.

These give birth to illusion.

Attentively contemplate this mind,

Empty, devoid of all objects.

If emotions should suddenly arise,

You will fall into confusion.

In a critical moment bring back the light,

Powerfully illuminating.

Clouds disperse, the sky is clear,

The sun shines brilliantly.

If nothing arises within the mind,

Nothing will manifest without.

That which has characteristics

Is not original reality.

If you can see a thought as it arises,

This awareness will at once destroy it.

Whatever state of mind should come,

Sweep it away, put it down.

Both good and evil states

Can be transformed by mind.

Sacred and profane appear

In accordance with thoughts.

Reciting mantras or contemplating mind

Are merely herbs for polishing a mirror.

When the dust is removed,

They are also wiped away.

Great extensive spiritual powers

Are all complete within the mind.

The Pure Land or the Heavens

Can be travelled to at will.

You need not seek the real,

Mind originally is Buddha.

The familiar becomes remote,

The strange seems familiar.

Day and night, everything is wonderful.

Nothing you encounter confuses you.

These are the essentials of mind.Han-Shan Te-Ch'ing was one of the four great Ch'an Masters who lived at the end of the Ming Dynasty. At the age of seven he already had doubts about his origin and destiny. At nine he entered a monastery, and at nineteen became a monk. His first attempts to practice Ch'an were fruitless, and he turned to reciting the Buddha's name, which brought better results. After this he resumed the practice of Ch'an with more success. While listening to the Avatamsaka Sutra, he realized that in Dharmadhatu, the realm of all phenomena, even the tiniest thing contains the whole universe. Later he read another book called "Things Not Moving, " and experienced another enlightenment. He wrote a poem which said:

Death and birth, day and night,

Water flowing, flowers withering,

It's only now I know

That nostrils point downwards.On another day, while walking, he suddenly entered samadhi, experienced a brilliant light like a huge, perfect mirror, with mountains and water, everything in the world reflected in it. When he returned from samadhi, his body and mind were completely clear; he realized there was nothing to attain. So he wrote this poem.

In the flash of one thought

My turbulent mind came to rest.

The inner and the outer,

The senses and their objects,

Are thoroughly lucid.

In a complete turnabout

I smashed the Great Emptiness.

The ten thousand manifestations

Arise and disappear

Without any reason.For many years as a wandering monk, he studied Ch'an under several leading masters and spent long periods living in solitude in the mountains. He engaged in altruistic acts, propagated the Dharma, and lectured on Sutras. He was a scholar and prolific writer, leaving behind many works on all aspects of Buddhism. He exemplified the bodhisattva ideal of developing wisdom through meditation, study, and compassionate action. In the spirit of his times, he did not make a strong distinction between the sects of Buddhism and was eclectic, incorporating elements of Confucianism. His style was a fusion of the austerity of Ch'an with the inclusive view of the Hua-Yen sect. To this day his undecayed body remains intact in the monastery of the Sixth Patriarch on mainland China.

"Contemplating Mind" is one among many of Master. Han Shan's poems and songs which deal with the approach one should take to practice. This short ming, or verse, describes practice as not going beyond mind and body-that there is nothing other than mind or body that can be used as tools of practice.

Look upon the body as unreal,

An image in a mirror,

Or the reflection of the moon in water.

Contemplate the mind as formless,

Yet bright and pure.The poet asks us to literally look upon the body as non-existent. In Buddhist analysis, form, taken to be the physical world, is the first of the five skandhas, or phenomenal aggregates. These aggregates, or "heaps, " together create the illusion of existence. Form is the material component. The other four skandhas ─ sensation, perception, volition, and consciousness-are all mental components. A person who is able to contemplate the five skandhas well would be considered enlightened. In Buddhist analysis, the body is composed of the four elements: earth, water, fire, and wind. If we were to separate these elements, our body would not exist. Why do these elements combine? They come together because of the force of our previous karma. A body which is thus compounded is not genuinely real. Being the result, or the reflection, of our previous karma, it is like the reflection of the moon in water. If the mind didn't create karma, then the elements would not accumulate and combine to make up the body. If we take this body, this result of previous mental karma, as real, then it's like looking upon the moon in the water as the real moon. Further, the body is in a constant state of change, and has no truly fixed existence. If we can realize the illusory nature of the body, the mind will settle down and our vexations will clear up. All our vexations, associated with greed, hatred, and delusion, arise because we identify with the body, and want to protect it and seek benefits for it. Because of the body, we give rise to the five desires, namely, food, sex, sleep, fame, and wealth. To undo vexations, first break the attachment to the body; then break away from the view that the body is truly substantial. But this view is very difficult to break. In the sutras it is said that sakaya, the view of having a body, is as difficult to uproot as a mountain. So, Han-Shan tells us, once we can see the body as unreal, we can begin to work on the mind.

The practice begins by contemplating the mind as formless. Ordinarily the mind has all kinds of forms or characteristics-greed, hatred, ignorance, pride, doubt, jealousy, and selfishness. They manifest mainly because of the body. Some people might think, "Death will end my vexations since I'll no longer have a body." But after you die you still have a body, and you will still have vexations. When this body is gone, a new one begins. Where there's a body there is vexation.

If the mind had fixed characteristics, it would not be changeable, and there would be no point in practicing. But the mind is always changing. The mind of the ordinary person is characterized by vexation, and the mind of a sage is characterized by wisdom; otherwise they are the same.

Not a single thought arising,

Empty, yet perceptive,

Still, yet illuminating,

Complete like the Great Emptiness,

Containing all that is wonderful.The mind that is without even one thought is extremely bright and pure, but this doesn't mean that it is blank. No thought means no characteristics, and blankness itself is a characteristic. In this condition the mind is unmoving, yet perceives everything very clearly. Although wisdom is empty, it is not without a function. What is this function? Without moving it reflects and illuminates everything. It is like the moon shining on water. Although each spot of water reflects a different image of the moon, the moon itself remains the same. But it doesn't say, "I shine." It just shines.

Great Emptiness has no limits. It gives rise neither to feelings of moving or not moving. Nothing detracts from its purity and brightness. This is the mind of wisdom. It is the mind of the Buddhas and bodhisattvas. It is also the ability to help sentient beings.

Neither going out nor coming in,

Without appearance or characteristics,To practice is to cultivate the mind. If you successfully contemplate the mind, all merits and functions within the mind are at your disposal. But as soon as one thought arises, everything is obscured. If while practicing you feel your mind expanding infinitely, that feeling gives you away. If you suddenly feel, "Ah! I've discovered a limitlessly great expanse! I am liberated!" in reality you are still within the sphere of the limited. Only neither-going-nor-coming is boundless. Being boundless, it has no circumference, so there's no way to find an entrance. To think of leaving is to imagine that there could be a better place, so there is no going either.

When Master T'ai-Hsu had his first enlightenment where he saw limitless light and sound, he felt he was in a very deep far away state. That was still not Great Emptiness since it was not without form. In his second experience there was nothing there that could be explained or described. If there was still something he could describe, it would not be formless.

Countless skillful means

Arise out of one mind.Skillful means, the various methods of helping oneself and others to liberation, are the bountiful yield of this practice. Liberation means going from ignorance to wisdom. The idea of ch'iao, translated as "mind" here, does not strictly refer to the mind of one thought. It is the original substance of infinitude. Ch'iao literally means a hole or cavity. In Chinese mythology, in the beginning the universe was a ball of chaos. Then a god came along and knocked a hole in it with a hammer. That caused the separation of heaven and earth, sun and moon, etc. Ch'iao also has the meaning of "wisdom." If you want to call it "mind, " you would have to say it's a pure mind.

Independent of material existence,

Which is ever an obstruction,

Do not cling to deluded thoughts.

These give birth to illusion.Like ch'iao, many words in this poem have a Taoist or Confucian origin. Two others are hsing and ch'i, literally, form and energy, translated here as "material existence." There is a saying: "What is above form is the Way, what is below form is Ch'i." The closest meaning of ch'i would be life-energy, it moves the universe. Where there is ch'i, there is also form. Although invisible, we see its effects, just as we see the wind in the swaying branches of a tree. "Material existence" includes all forms and energy, both visible and invisible. Wherever there is energy and form, there is also obstruction. So please do not rely on material existence to overcome delusion ─ it is the cause of delusion.

What are deluded thoughts? When meditating are you aware of wandering thoughts? Hopefully you are. But in daily life do you actually believe in your experiences, your plans, your abilities, your knowledge? What are these? Just a series of more or less connected delusions. If you act on delusions, all kinds of strange things may come up. (The word translated here as "illusion" means that which is weird or strange.) The more firmly you believe in them, the more likely they are to arise.

Delusions are usually created by the five desires. To fulfill the demands of the five desires, people seek the satisfactions of material things, and of the flesh. In the end, are you really satisfied? After eating a meal, are you satisfied? Of course you are, for the moment. But a few hours later your craving for food begins anew. It's an endless cycle; not only are you concerned about getting food now, but this worry follows you into old age. Truly there is no end to desire.

Attentively contemplate this mind,

Empty, devoid of all objects.

If emotions should suddenly arise,

You will fall into confusion.If we contemplate the mind well, we discover there is nothing in it. If there is something in it, such as an emotion, then there is still attachment. It is only necessary for you to give rise to a momentary or sudden emotion to set your mind in motion.

In a critical moment bring back the light,

Powerfully illuminating.When you find yourself muddled, you should realize it right away and tell yourself, "This is false, an attachment." That way your wisdom will come into play and grow in power. The difficulty is that you may not always recognize your confused state. According to the patriarchs enlightenment is very easy. You must use wisdom to shine on all your delusions. But someone in the confused state supposes that the way he sees things is real, that he is very clear. Therefore he can't begin to think about searching for the light of wisdom. Only if you realize your confusion, then, in a dangerous place, you can turn around.

Clouds disperse, the sky is clear,

The sun shines brilliantly.Realizing your delusion, if through practice you could illuminate the mind that is originally empty, it would be like the sky after dark clouds have dispersed. Sometimes while practicing you seem to have no thoughts; still, your mind is not really clear. This would be like a hot, hazy day when vapor rises and obscures the sun. Sometimes, after a few days of retreat, I ask people how close they think they are to enlightenment. Some say, "Well, it seems like it's right around the corner, but I can't see it." Sometimes around the edges of a dark cloud we can see rays of sunlight, so we know that the sun is there. Only by seeing it yourself will you know that a brilliant sun shines behind the cloud. Those who have seen some rays of light will become firm in their faith and will practice harder.

if nothing arises within the mind,

Nothing will manifest without.

That which has characteristics

Is not original reality.If no thoughts arise, nothing will be experienced outside of the mind. If you think that something is manifesting without, it is an illusion. In the Platform Sutra it says that neither the flag nor the wind moves. It is the mind that moves. When the mind is still, there is nothing outside that can tempt or disturb you. Do the thoughts that disturb you come from outside or inside? If only inside thoughts bother you, then you are practicing well. But even getting to this point is not easy.

Feelings that relate to our own body, such as hunger, heat, cold, or pain, are really outer things. Other thoughts may arise that originate in the mind. For example, I may say to people, "Tell me when the body and the method disappear and I'll give you a new method." So during their sitting, they may be thinking, "Strange. How is it that my body is still here? Body ─ go quickly! Get lost! I want a new method." Then when the body finally disappears, they think, "What's this? How come the method is still here? When will it disappear? Shih-fu told us about infinite light and sound. Why haven't I experienced that yet? Maybe it's coming soon. But why can't I get anywhere? Ah! Shih-fu told us not to think like this. Better not force anything. He tells us not to think of enlightenment. O.K., I won't think of it, I'll just practice. This time, I won't be afraid of dying. But it seems like I can't die. Why?"

These conversations with yourself while meditating are not related to the body or the outer environment; they originate in the mind. These are meaningless delusions, mental chaos. How do you get rid of this chaos? Very simple. As soon as a thought comes up, just ignore it and go back to the method. Whether it originates in your mind or in the environment, it lacks reality. Some people may say, "I know I am confused, but I can't do anything about it." That is why practice is needed-to help those who at least recognize their confusion do something about it.

If you can see a thought as it arises,

This awareness will at once destroy it.

Whatever state of mind should come,

Sweep it away, put it down.There is a saying about the practice: "Don't be afraid of a thought arising, just be afraid of noticing it too late." It's not such a terrible thing for thoughts to arise. The problem is when you're not aware of them. If you realize it as soon as a thought arises, then it doesn't matter. It will help you to work harder. If there were no thoughts arising at all, you would already have a pure mind and you wouldn't need to practice. People who have never practiced may know about their wandering thoughts but can do nothing to stop them.

When you are practicing hard, whatever thought comes up you have the power to just sweep it away. To sweep means to ignore, not to dislike or to resist the thought. How else could you sweep it away? If you resist it with something else, that something else is also a thought. If I wanted to get rid of Tom, and got Dick to do the job, after Tom left I would still be stuck with Dick. No matter how many people I find to get the other one out, there would always be one left. If you get involved with feelings after the thought is already gone, thinking, "What bad luck. I hope it doesn't come up again, " your mind will definitely be scattered. Then you begin to think, "I'm hopelessly sunk in wandering thoughts. I'll just give up meditating." If you work like this, the wandering thoughts don't get swept away, they just accumulate. This is because you haven't put down the state of mind which gave rise to the thoughts in the first place.

Or are you the type who tries to grab the wandering thought and say to it, "I'm going to let you come again." Can you do that? Actually, if you are really able to grab hold of it, at least you have the intention of watching it. If you were to continue watching that thought, then that very state of mind would become your method. Is that possible? Some people start to work on "What is Wu?" and it eventually becomes "What am I?" Then they even forget that and they just work on "I, I, I." One student started working on "What is Wu?" and ended up by asking "Where is my heart?" I told him that wasn't the right question, he should be working on Wu. But he kept on looking all over for his heart. Finally he picked up a feather outside and said, "Oh! Here's where my heart is!" If you can take a wandering thought and just fix onto it without letting go, this in itself becomes a method. If you can't hold onto it, then any thought, good or bad, is a delusion that disturbs your practice. The most important thing is, whatever is past, just let it go. Your mind should be like a mirror, not a camera. Whatever goes into a camera is recorded there; the reflection in a mirror vanishes when the object moves away.

Both good and evil states

Can be transformed by mind.

Sacred and profane appear

In accordance with thoughts.Everything is a product of your mind. If the mind didn't move, no discriminations would be made. According to your situation you will see certain things as good or bad. But this is always changing, and the things themselves don't have any of these fixed characteristics. There is no defintite standard of good and evil; it all depends on your viewpoint at the moment.

The state of a person's mind makes him perceive some people as common, others as holy. To some people Jesus was really an evil person who ought to be killed. To his disciples, he was a saint. One student, after she worked very hard on a retreat, said she saw a light emanating from my body. So she knelt down, taking me for a holy man. Later on, when she discontinued practicing Ch'an, she just saw me as a common person again. According to Buddha Dharma, saintliness or ordinariness are in the mind of the beholder. Even the saintliness of such people as the Buddha or Jesus are value judgments.

When the Buddha looks at sentient beings, all sentient beings are just Buddha. When sentient beings look at the Buddha, what do you think they see? When Sakyamuni Buddha walked through the forests, or on the banks of the Ganges, do you think all the birds, ants, and other little animals saw a Buddha? If you were living at that time and had never heard of this person, Sakyamuni, when you saw him, would you think he was the Buddha, or just another wandering ascetic?

When we perceive something, that is only our idea of what exists. If I looked around this room without making discriminations of any kind, what would I see? Nine people? One person? In reality I would see not even one. If I see even one, my mind has attached to form. Understand?

Reciting mantras or contemplating mind

Are merely herbs for polishing a mirror.

When the dust is removed,

They are also wiped away.Methods of cultivation are useful for those who are in the course of training. For those people who have reached the stage of no thought, who have completed the course of practice, methods are not needed. Some people ask themselves when they are working well, "Am I still working on the method? Where did the method go?" Originally they were working well, but this kind of thought ruins their concentration. It is like a pair of glasses that fit so naturally on you that you somehow forget you are wearing them and start looking for them. When you are working well on your method, forget that you are using a method. When you cross a bridge, once you get to the other side you wouldn't say, "Where did the bridge go?" The method is just a tool to get to your destination. Once you have arrived, it is of no more use to you.

Great extensive spiritual powers

Are all complete within the mind.Some people are always looking for someone to give them some kind of psychic power, or trying to get some other benefit from someone with power. One student thought that I could give people power to make them progress more quickly, and that I could obstruct others from making progress. In the beginning he had some benefit from the practice and felt I was a very good master. Sometime later, when he didn't have much success, he felt that I was obstructing him with some magic spell. Another person told me that a Zen master used spiritual power to ruin his family life and unsettle his mind. He asked me to give him some power to combat the other master. I told him, "That person is a Ch'an master, and according to the spirit of Ch'an, he would not do something like that." But he said, "No, he really does have this power. If I don't go to his place, then my problems begin." So I said, "Then you should go regularly." Actually, none of this was happening. It was all in his mind.

We call this "practicing outer paths" because your faith is not in yourself but only in outer things. The usual interpretation of the Chinese term wai tao is "outside of Buddhist belief, " that is, heretical. But the real meaning of outer paths is seeking salvation outside oneself, such as another person, a god, or even a Buddha. As such, some Buddhists may be following outer paths. Your fate is your own; to rely on somebody else is foolish.

People have the potential for great spiritual power. We find it in all religions. But these powers should not be used arbitrarily. Not that the power is not available, but you wouldn't get very far with it because it cannot undo the power of people's karma. Most Ch'an masters have a certain degree of spiritual power but have a policy of not using them, I myself claim no psychic powers, but I do have a kind of perception-response, or sensitivity to situations. But the kind of perception-response I have depends on the situation at the moment. Because spiritual powers are not reliable and are dangerous to use, I have never sought them. People may like it as a novelty, but after a while they get bored. Such supernatural powers can only stimulate or excite; they don't give people a lasting sense of security. To my mind these things are of no use.

Another kind of spiritual power is using the power of our minds to communicate, to set up karmic affinities, with sentient beings. For example, wise people or religious leaders may give a lecture that moved people to become converted on the spot. In this sense, Jesus, Sakyamuni, and Confucius are all people with great spiritual powers. As for Great Master Ou-l of the Ming dynasty, in his lifetime, the biggest recorded audience that ever attended his lectures was fourteen people. But this master has had a great influence on Chinese Buddhism. So the best kind of spiritual power is that which benefits people down through the ages, not just a cheap thrill or excitement. Your own mind is the source of all the power you need.

The Pure Land or the Heavens

Can be travelled to at will.If your mind is pure, then wherever you are will also be pure. If you have a heavenly mind, then you are in heaven. If you're feeling very miserable, you're in hell. But the sad thing is, most people can so freely go to hell, but not so freely to heaven. If I were to grab you right now and give you a good scolding, and you said, "I didn't do anything wrong. What are you yelling at me for?" At that time your mind would be full of misery and vexations. You would be in hell. But if, when I scolded and beat you, you were to turn around, bow deeply, with tears running down your cheeks, and say, "I am so grateful for the chance to burn up some of my great karmic obstruction, " you would be in heaven. But to have a mind like that is rather rare. So these two lines at first glance look strange, but the Pure Land, the heavens, can all be experienced right here in the ordinary world.

You need not seek the real,

Mind is originally Buddha.There is no such thing as the real mind. Ridding yourself of delusion: that's the real mind. There is also no Buddha. Your own mind is originally Buddha. If the mind is pure, even the Buddha isn't there. When you have no thought of becoming a Buddha, when there is no Buddha and no vexations, that is the real Buddha mind.

The familiar becomes remote,

The strange seems familiar.

Day and night, everything seems wonderful.

Nothing you encounter confuses you.

These are the essentials of mind.When the familiar becomes remote you look upon your family as strangers, and upon strangers as dear, close kin. Only a person with true practice can do this. But if you haven't practiced deeply and consider your parents as outsiders, without also considering outsiders as your parents, you're off the mark. When your practice becomes very deep, you will see all sentient beings as your parents. This is because your fortuitous birth as a human being was the result of many eons of cause and effect, involving untold numbers of sentient beings. Knowing this, you feel a deep sense of gratitude towards everyone and everything. Others have done much for you, and you want to express your gratitude.

But you only have one body. How can you help all sentient beings as if they were your own parents? Don't burden yourself with such thoughts. Day and night, keep your mind on the one thought of working hard. if, moment by moment, you can keep your mind in a clear state, then nothing will confuse you, and you will be able to express your gratitude freely, naturally, without obstruction.

We have talked about the poem "Contemplating Mind," which describes the general situation of the mind, and Han-Shan's explanation of practice and enlightenment. This talk is based on my own experience, making use of the verse, aiming to guide you in your practice.

Essentials of Practice and Enlightenment for Beginners

By Master Hanshan Deqing [1546-1623]

Translation by Guo-gu Shi

I. How to Practice and Reach Enlightenment

Concerning the causes and condition of this Great Matter, [this Buddha-nature] is intrinsically within everyone; as such, it is already complete within you, lacking nothing. The difficulty is that, since time without beginning, seeds of passion, deluded thinking, emotional conceptualizations, and deep-rooted habitual tendencies have obscured this marvelous luminosity. You cannot genuinely realize it because you have being wallowing in remnant deluded thoughts of body, mind, and the world, discriminating and musing [about this and that]. For these reason you have been roaming in the cycle of birth and death [endlessly]. Yet, all Buddhas and ancestral masters have appeared in the world using countless words and expedient means to expound on Chan and to clarify the doctrine. Following and meeting different dispositions [of sentient being], all of these expedient means are like tools to crush our mind of clinging and realize that originally there is no real substantiality to “dharmas” or [the sense of] “self.”

What is commonly known as practice means simply to accord with [whatever state] of mind youíre in so as to purify and relinquish the deluded thoughts and traces of your habit tendencies. Exerting your efforts here is called practice. If within a single moment deluded thinking suddenly ceases, [you will] thoroughly perceive your own mind and realize that it is vast and open, bright and luminousóintrinsically perfect and complete. This state, being originally pure, devoid of a single thing, is called enlightenment. Apart from this mind, there is no such thing as cultivation or enlightenment. The essence of your mind is like a mirror and all the traces of deluded thoughts and clinging to conditions are defiling dust of the mind. Your conception of appearances is this dust and your emotional consciousness is the defilement. If all the deluded thoughts melt away, the intrinsic essence will reveal in its own accord. Itís like when the defilement is polished away, the mirror regains its clarity. It is the same with Dharma.

However, our habit, defilement, and self-clinging accumulated throughout eons have become solid and deep-rooted. Fortunately, through the condition of having the guidance of a good spiritual friend, our internal prajna as a cause can influence our being so this inherent prajna can be augmented. Having realized that [prajna] is inherent in us, we will be able to arouse the [Bodhi-] mind and steer our direction toward the aspiration of relinquishing [the cyclic existence of] birth and death. This task of uprooting the roots of birth and death accumulated through innumerable eons all at once is a subtle matter. If you are not someone with great strength and ability brave enough to shoulder such a burden and to cut through directly [to this matter] without the slightest hesitation, then [this task] will be extremely difficult. An ancient one has said, “This matter is like one person confronting ten thousand enemies.” These are not false words.

II. The Entrance to Practice and Enlightenment

Generally speaking, in this Dharma-ending-age, there are more people who practice than people who truly have realization. There are more people who waste their efforts than those who derive power. Why is this? They do not exert their effort directly and do not know the shortcut. Instead, many people merely fill their minds with past knowledge of words and language based on what they have heard, or they measure things by means of their emotional discriminations, or they suppress deluded thoughts, or they dazzle themselves with visionary astonishment at their sensory gates. These people dwell on the words of the ancient ones in their minds and take them to be real. Furthermore, they cling to these words as their own view. Little do they know that none of these are the least bit useful. This is what is called, “grasping at otherís understanding and clouding oneís own entrance to enlightenment.”

In order to engage in practice, you must first sever knowledge and understanding and single-mindedly exert all of your efforts on one thought. Have a firm conviction in your own [true] mind that, originally it is pure and clear, without the slightest lingering thingóit is bright and perfect and it pervades throughout the Dharmadhatu. Intrinsically, there is no body, mind, or world, nor are there any deluded thoughts and emotional conceptions. Right at this moment, this single thought is itself unborn! Everything that manifests before you now are illusory and insubstantialóall of which are reflections projected from the true mind. Work in such a manner to crush away [all your deluded thoughts]. You should fixate [your mind] to observe where the thoughts arise from and where they cease. If you practice like this, no matter what kinds of deluded thoughts arise, one smash and they will all be crushed to pieces. All will dissolve and vanish away. You should never follow or perpetuate deluded thoughts. Master Yongjia has admonished, “One must sever the mind [that desires] continuation.” This is because the illusory mind of delusion is originally rootless. You should never take a deluded thought as real and try to hold on to it in your heart. As soon as it arises notice it right away. Once you notice it, it will vanish. Never try to suppress thoughts but allow thoughts to be as you watch a gourd floating on water.

Put aside your body, mind, and world and simply bring forth this single thought [of method] like a sword piercing through the sky. Whether a Buddha or a Mara appears, just cut them off like a snarl of entangled silk thread. Use all your effort and strength patiently to push your mind to the very end. What is known as, “a mind that maintains the correct thought of true suchness” means that a correct thought is no-thought. If you are able to contemplate no-thought, youíre already steering toward the wisdom of the Buddhas.

Those who practice and have recently generated the [Bodhi-] mind should have the conviction in the teaching of mind-only. The Buddha has said, “The three realms are mind-only and the myriad dharmas are mere consciousness.” All Buddhadharma is only further exposition on these two lines so everyone will be able to distinguish, understand, and generate faith in this reality. The passages of the sacred and the profane, are only paths of delusion and awakening with in your own mind. Besides the mind, all karmas of virtue and vice are unobtainable. Your [intrinsic] nature is wondrous. It is something natural and spontaneous, not something you can “enlighten to” [since you naturally have it]. As such, what is there to be deluded about? Delusion only refers to your unawareness that your mind intrinsically has not a single thing, and that the body, mind, and world are originally empty. Because youíre obstructed, therefore, there is delusion. You have always taken the deluded thinking mind, that constantly rises and passes away, as real. For this reason, you have also take the various illusory transformations in and appearances of the realms of the six sense objects as real. If today you are willing to arouse your mind and steer away from [this direction] and take the upper road, then you should cast aside all of your previous views and understanding. Here not a single iota of intellectual knowledge or cleverness will be useful. You must only see through the body, mind, and world that appear before you and realize that they are all insubstantial. Like imaginary reflectionsóthey are the same as images in the mirror or moon reflected in the water. Hear all sounds and voices like wind passing through the forest; perceive all objects as drifting clouds in the sky. Everything is in a constant state of flux; everything is illusory and insubstantial. Not only is the external world like this, but your own deluded thoughts, emotional discriminations of the mind, and all the seeds of passion, habit tendencies, as well as all vexations are also groundless and insubstantial.

If you can thus engage in contemplation, then whenever a thought arises, you should find its source. Never haphazardly allow it to pass you by [without seeing through it]. Do not be deceived by it! If this is how you work, then you will be doing some genuine practice. Do not try to gather up some abstract and intellectual view on it or try to fabricate some cleaver understanding about it. Still, to even speak about practice is really like the last alternative. For example, in the use of weapons, they are really not auspicious objects! But they are used as the last alternative [in battles]. The ancient ones spoke about investigating Chan and bringing forth the huatou. These, too are last alternatives. Even though there are innumerable gong ans, only by using the huatou, “Who is reciting the Buddhaís name?” can you derive power from it easily enough amidst vexing situations. Even though you can easily derive power from it, [this huatou] is merely a [broken] tile for knocking down doors. Eventually you will have to throw it away. Still, you must use it for now. If you plan to use a huatou for your practice, you must have faith, unwavering firmness, and perseverance. You must not have the least bit of hesitation and uncertainty. Also, you must not be one way today and another tomorrow. You should not be concerned that you will not be enlightened, nor should you feel that this huatou is not profound enough! All of these thoughts are just hindrances. I must speak of these now so that you will not give rise to doubt and suspicion when you are confronted [by difficulties].

If you can derive power from your power, the external world will not influence you. However, internally your mind may give rise to much frantic distraction for [seemingly] no reason. Sometimes desire and lust well up; sometime restlessness comes in. Numerous hindrances can arise inside of you making you feel mentally and physically exhausted. You will not know what to do. These are all of the karmic propensities that have been stored inside your eighth-consciousness for innumerable eons. Today, due to your energetic practice, they will all come out. At that critical point, you must be able to discern and see through them then pass beyond [these obstacles]. Never be controlled and manipulated by them and most of all, never take them to be real. At that point, you must refresh your spirit and arouse your courage and diligence then bring forth this existential concern with your investigation of the huatou. Fix your attention at the point from which thoughts arise and continuously push forward on and on and ask, “Originally there is nothing inside of me, so where does the [obstacle] come from? What is it?” You must be determined to find out the bottom of this matter. Pressing on just like this, killing every [delusion in sight,] without leaving a single trace until even the demons and spirits burst out in tears. If you can practice like this, naturally good news will come to you.

If you can smash through a single thought, then all deluded thinking will suddenly be stripped off. You will feel like a flower in the sky that casts no shadows, or like a bright sun emitting boundless light, or like a limpid pond, transparent and clear. After experiencing this, there will be immeasurable feelings of light and ease, as well as a sense of liberation. This is a sign of deriving power from practice for beginners. There is nothing marvelous or extraordinary about it. Do not rejoice and wallow in this ravishing experience. If you do, then the Mara of Joy will possess you and you will have gained another kind of obstruction! Concealed within the storehouse consciousness are your deep-rooted habit tendencies and seeds of passion. If your practice of huatou is not taking effect, or that youíre unable to contemplate and illuminate your mind, or youíre simply incapable of applying yourself to the practice, then you should practice prostrations, read the sutras, and engage yourself in repentance. You may also recite mantras to receive the secret seal of the Buddhas; it will alleviate your hindrances. This is because all the secret mantras are the seals of the Buddhasí diamond mind. When you use them, it is like holding an indestructible diamond thunderbolt that can shatter everything. Whatever comes close to it will be demolished into dust motes. The essence of all the esoteric teachings of all Buddhas and ancestral masters are contained in the mantras. Therefore, it is said that, “All Tathagatas in the ten directions attained unsurpassable and correct perfect enlightenment through such mantras.” Even though the Buddhas have said this clearly, the lineage ancestral masters, fearing that these words may be misunderstood, have kept this knowledge a secret and do not use this method. Nevertheless, in order to derive power from using a mantra, you must practice it regularly after a long and extensive period of time. Yet, even so, you should never anticipate or seek miraculous response from using it.

III. Understanding-enlightenment and Actualized-enlightenment

There are those who are first enlightened then engage in practice, and there are others who first practice and then get enlightened. Also, there is a difference with understanding-enlightenment and actualized-enlightenment.

Those who understand their minds after hearing the spoken teaching from the Buddhas and ancestral masters reach an understanding-enlightenment. In most cases, these people fall into views and knowledge. Confronted by all circumstances, they will not be able to make use of what they have come to know. Their minds and the external objects are in opposition. There is neither oneness nor harmony. Thus, they face obstacles all the time. [What they have realized] is called “prajna in semblance” and is not from genuine practice.

Actualized-enlightenment results from solid and sincere practice when you reach an impasse where the mountains are barren and waters are exhausted. Suddenly, [at the moment when] a thought stops, you will thoroughly perceive your own mind. At this time, you will feel as though you have personally seen your own father at a crossroadóthere is no doubt about it! It is like you yourself drinking water. Whether the water is cold or warm, only you will know, and it is not something you can describe to others. This is genuine practice and true enlightenment. Having had such experience, you can integrate it with all situations of life and purify, as well as relinquish, the karma that has already manifested, the stream of your consciousness, your deluded thinking and emotional conceptions until everything fuses into the One True [enlightened] Mind. This is actualized-enlightenment.

This state of actualized-enlightenment can be further divided into shallow and profound realizations. If you exert your efforts at the root [of your existence], smashing away the cave of the eighth consciousness, and instantaneously overturn the den of fundamental ignorance, with one leap directly enter [the realm of enlightenment], then there is nothing further for you to learn. This is having supreme karmic roots. Your actualization will be profound indeed. The depth of actualization for those who practice gradually, [on the other hand,] will be shallow.

The worst thing is to be self-satisfied with little [experiences]. Never allow yourself to fall into the dazzling experiences that arise from your sensory gates. Why? Because your eighth consciousness has not yet been crushed, so whatever you experience or do will be [conditioned] by your [deluded] consciousness and senses. If you think that this [consciousness] is real, then it is like mistaking a thief to be your own son! The ancient one has said, “Those who engage in practice do not know what is real because until now they have taken their consciousness [to be true]; what a fool takes to be his original face is actually the fundamental cause of birth and death.” This is the barrier that you must pass through.

So called sudden enlightenment and gradual practice refers to one who has experienced a thorough enlightenment but, still has remnant habit tendencies that are not instantaneously purified. For these people, they must, implement the principles from their enlightenment that they have realized to face all circumstances of life and, bring forth the strength from their contemplation and illumination to experience their minds in difficult situations. When one portion of their experience in such situations accords[with the enlightened way], they will have actualized one portion of the Dharmakaya. When they dissolve away one portion of their deluded thinking, that is the degree to which their fundamental wisdom manifests. What is critical is seamless continuity in the practice. [For these people,] it is much more effective when they practice in different real life situations.

Comments by the Translator

Hanshan Deqing [1546-1623] is considered one of the four most eminent Buddhist monks in the late Ming Dynasty [1368-1644] partly for his social-political interactions with Ming court, exegesis of Buddhist texts, and most importantly, for his Chan practice. In this short introduction, I will only comment briefly on the last aspects on his contributions to Chinese Buddhism.

Even at age seven, Hanshan had existential concerns about life and death. These thoughts had led him to leave the household life and pursue a life of Buddhist training already at age nine. At the age of 19, he was ordained as a Buddhist monk.

In all of the history of Chan, there is not a single master that has written in such detail about his own practice and experiences, especially in describing the enlightened state of mind. According to a compiled record, The Dream Roaming of Great Master Hanshan, he had numerous and extraordinary enlightenment experiences. His first experience was during a Dharma lecture when he heard the profound teaching on the interpenetration of phenomena as taught in the Avatamsaka Sutra and the treatise, The Ten Wondrous Gates. He experienced another deep enlightenment experience sometime later when at Mt. Wu Tai he read the treatise by an early Chinese Madhyamika monk called Things do not Move. According to the record, Hanshan served as proofreader of the Book of Chao, the source of Things do not Move. Hanshan came across the stories of a Bramacharin who had left home in his youth and returned when he was white-haired. When people saw him, the neighbors asked, “Is that man [whom we know] still living today?” The Bramacharin replied, “I look like that man of the past, but I am not he.” On reading this story ,, Hanshan suddenly understood that all things do not come and go. When he got up from his seat and walked around, he did not see things in motion. When he opened the window blind, suddenly a wind blew the trees in the yard, and the leaves flew all over the sky. However, he did not see any signs of motion. When he went to urinate, he still did not see signs of flowing. He understood what the text spoke of as, “Streams and rivers run into the ocean and yet there is no flowing.” At this time, Hanshan shattered all doubt and existential concerns about birth and death. He wrote the following poem:

Life and death, day and night;

Water flows and flowers fall.

Only today, I know that

My nose points downward!The next day when another great Chan Master, Miaofeng, saw him, he knew that Hanshan was different and asked him whether anything has happened. Hanshan replied, ” Last night I saw two iron oxen fighting with each other next to the river bank. They both fell in the river. Since then, I have not heard anything about them.” Miaofeng rejoiced and congratulated him.

Still, on another occasion, after a meal, Hanshan walked in the mountains and experienced a profound state of samadhi while standing. In the record, it described that suddenly he lost all consciousness of his body and mind. He experienced everything, the whole universe, as contained in a great perfect mirror-like mind. Mountains and rivers all reflected in it. After he came out of that experience, he wrote the following verse:

In an instant of thought, this chaotic mind is put to rest.

Internally and externally, the sense faculties and objects

Became empty and clear.

Overturning the bodyóemptiness is now shattered.

The myriad forms and appearances arise and extinguish

[in their own accord].These are just some of his experiences recorded in The Dream Roaming of Great Master Hanshan. The instructions on practice that I have translated here are from the second fascicle of this record. The original text had no titles but were letters written to a lay practitioner on Chan practice.

Hanshan was also a prolific writer whose published works ranging from commentaries on Buddhist sutras and treatises, to secular poems, reached the length of 8,300 pages. In The Dream Roaming of Great Master Hanshan, there are 55 chuan, or books, covering over 3,000 pages. His commentaries on the Supplement to the Tripitaka consist of 119 chuan, covering over 1,200 large pages printed on both sides. Like other Ming Dynasty Buddhist monks, he also wrote many commentaries on non-Buddhist works such as Lao Zi and Zhuang Zi, as well as other Taoist and Confucian text.

His contributions to Chinese Buddhism lies in his exemplary personality and his striving toward liberation, especially in an age of mismanaged government, corruption, internal oppression, and the external vulnerability of the Ming Dynasty. Although his Buddhist commentary is not particularly original, the strength of his writing comes from his active approach in reviving and popularizing Buddhism, and in the way he responded to the times in which he lived.

From all that we know of Hanshan, we can conclude that he was a great master who gave equal weight to doctrine and practice, as well as to the revival of Chinese Buddhism.

Instructions in the Critical Essentials of Cultivating Dhyana Meditation

By the Ming Dynasty Dhyana Master Han-shan De-ching

Translated by Dharmamitra

From The Records of Dream Wanderings

The particular lineage of the dhyana gateway transmits the seal of the buddha mind. Originally, it was not a subtle matter. Beginning with Bodhidharma's coming from the west, the idea of exclusive transmittal became established and the four fascicles of the La'nkaavataara were taken as the [basis for] the seal of the mind. This being the case, although dhyana constituted a separate transmittal outside of the teachings, in actuality, it is because the teachings bring forth a corresponding realization that one then [succeeds in] perceiving the non-dual path of the buddhas and patriarchs. The very meditative skills which are employed during one's investigations [into dhyana] come forth from the teachings themselves.

The La'nkaavataara states, "When sitting quietly in the mountains and forests, at superior, middling and lower levels of cultivation one is able to perceive the flow of the false thinking in one's own mind." This is in fact the World Honored One's clear instruction in the formulary method of developing meditative skill. It also states, "His intellectual mind consciousness is a manifestation of his own mind. The false marks of the experiential state associated with one's self nature [manifest as] the sea of existence within the realm of birth and death. [They arise from] karmic action, desire and ignorance. Such causes as these may all be transcended thereby." This constitutes the Thus Come One's clear instruction in the marvelous principle of how to awaken the mind. It also states, "From all of the sages of the past it has been passed on in turn, being [both] transmitted and received that false thinking is devoid of an [inherently existent] nature." This is also a clear instruction in the [basis of] the secret mind seal.

This golden-countenanced elder's(1) instructions to people on the critically essential points of [dhyana] investigation were [continued on like this] until Bodhidharma instructed the second patriarch, saying, "You need only release (lit. "exhale") all conditions in the external sphere. The inner mind will then have nothing to draw in (lit. "inhale"). The mind will then become like a wall. You will then be able to enter the Way." This was Bodhidharma's very first essential dharma employed in instructing people how to carry out meditative investigations.

[The tradition] was transmitted on until the time when Hwang Mei, [the Fifth Patriarch], sought a Dharma heir. The Sixth Patriarch had just proclaimed his realization that, "Fundamentally, there is nothing whatsoever" when he then obtained the robe and bowl. This was a clear indication of the transmittal of the seal of the mind.

Next, the Sixth Patriarch returned to the South and instructed Dao Ming, saying, "Don't think of good. Don't think of bad. Right then, what is the original countenance of the senior-seated Ming?" This was the Sixth Patriarch's first instruction to people in the clear formula for [dhyana] investigation.

From these [examples] we know that as it came down to us from the Buddha and the patriarchs the intent was only to instruct a person in obtaining a complete awakening to his own mind and in the recognition [of the true nature] of the "self," that's all. There still had not yet been any discussion of a gung-an (i.e. "anecdote") or a hwa-tou (lit. "speech-source"). When it came to Nan Ywe, Ching Ywan and those who came after them, all of the patriarchs accorded with what was appropriate in providing their instructions. For the most part they went to the place of doubt and knocked there in order to cause a person to turn his head around, reverse the direction of his thinking and then put it [all] to rest. But then it came about that there were those who were unable [to respond to this technique] so that even though one might bang away with the hammer and tongs, one still had no choice but to let [one's teaching] adapt to [the student's] appropriate time and conditions.

When it reached Hwang Bwo was when there first occured the instruction of people in [the practice of] looking into a hwa-tou. [This was the practice] straight on down to Dhyana Master Da Hwei who then engaged in the extremely strong promotion of teaching students to investigate into a gung-an (lit. "anecdote") which was used as an aid. This was referred to as a hwa-tou (lit. "speech source"). It was required of a person that he very closely engage in the bringing up and "tearing into" it.

Why was this? It was done on account of the fact that in every thought the seeds of evil practices from an incalculable number of kalpas permeate internally within the field of the eighth consciousness. They flow on continuously [with the result that] false thinking is not cut off and there is nothing which [most people] can do about it. Hence he would take a phrase of words devoid of any meaning-based flavor and give it to you for you to bite into it and hold it down.

Formerly one would take all internally and externally related false thinking in one's mind state and put it all down at once. But because one became unable to put it down he then taught one to bring up this hwa-tou. Then, just like chopping off tangled strands of silk, in a single cut they were all cut off evenly such that they did not continue on any more. One cut off the intellectual mind consciousness so that it was no longer allowed to be active. This is precisely the same as Bodhidharma's principle of "You need only release (lit. "exhale") all conditions in the external sphere. The inner mind will then have nothing to draw in (lit. "inhale"). The mind will then become like a wall."

If one fails to take on the task in this fashion, one will certainly fail to perceive one's original countenance. The intention is not to teach you to deliberate on [the meaning of] the sentence in the gung-an. One should develop a sentiment of doubt and look to it as a means for seeking a measure of realization. This is just exactly like [the instruction offered by] Da Hwei who exclusively taught the looking into the hwa-tou as the invoking of a deadly stratagem whereby he simply wanted you to engage in an assassin's surprise attack on the mind, that's all. As an example [of his teaching], he instructed the assembly, saying, "When engaging in dhyana investigation one must empty out the mind and take the two words 'birth' and 'death' and stick them up on your forehead. [One should feel] as if he owed ten-thousand strings of cash. In the three [periods] of the day and the three [periods] of the night, whether drinking tea or eating meals, when walking and when standing, when sitting and when lying down, when toasting with friends, at quiet times and at boisterous times, one still keeps bringing up the hwa-tou: 'Does a dog have the buddha nature, or not?' Jou said, 'No.'

"One should only be concerned about looking one way and looking another [so that] when there is no flavor [anymore] then it will be like running right into a wall. When one gets to the source where things come together, then it is like when a mouse [runs headlong] into a bull's horn and then finds the route cut off. The intent is that you succeed in bringing about the single entity of the long-enduring and distantly-extending body and mind with which one carries on a struggle [with the result that] suddenly the flower of the mind puts out a brightness which illuminates the k.setras of the ten directions. With a single awakening one then reaches right down to the very bottom of things."(2)

The above [teaching] is the set of hammer and tongs routinely employed by the old eminence Da Hwei. His intent was just that he wanted you to take the hwa-tou and use it to block up and cut off the false thinking set loose by the intellectual mind faculty with the result that its flowing on would no longer be active. It is just at that point where it is not being active that one succeeds in seeing one's original countenance.

It is not the intent to instruct you to carry on deliberative thinking about [the meaning of] the gung-an. One should employ the sentiment of doubt as a means for seeking a measure of realization. For example, it was [also] stated, "As for the flower of the mind putting forth brightness, how could that be something obtained from someone else?"

Instruction such as that presented above has been set forth by each and every one of the buddhas and patriarchs with the intention that you investigate into yourself and refrain from seizing on and peering into someone else's esoteric and marvelous phrases. As for the people of the present era, in discussing investigations undertaken in dhyana and the application of meditative skill, everyone speaks of looking into the hwa-tou and bringing the sentiment of doubt to bear, but they do not realize that one must go to the very root [of the matter]. And so they are only concerned with seeking at the level of the hwa-tou.

They seek coming and they seek going and then suddenly visualize a scene full of light and declare that they have awakened. They then speak forth a verse and present a piece of poetry making as if they had become especially exotic goods. They then take it that they have succeeded in gaining complete understanding. They are completely unaware that they have fallen entirely into the net of knowledge and vision based on false thinking. When one goes about dhyana investigations in this manner, doesn't this amount to poking out the eyes of everyone in the entire world of later generations?

The younger generation of today have not even gotten their sitting cushions warm when they proclaim that they have awakened to the Way. They then rely on their mouths, start channeling sprites and ghosts, fall into the quick-and-smart verbal swordplay, and then think up a few sentences of foolish words and scrambled discourse which are utterly baseless. They proclaim it to be an "Ode to the Ancients." This is just something which has come forth from your own false thinking. And was it ever really so that you even saw the ancients here even in a dream?

If it was actually so easy to become awakened to the Way as [claimed by] people of the present, then considering the integrity of practice of ancients such as Chang Ching who wore out seven sitting cushions and Chao Jou who for thirty years permitted no unfocused use of mind, those ancients had to have been of the very dullest of faculties. They wouldn't even be fit to serve you moderns by holding your straw sandals! When people of overweening arrogance claim to have realizations when they have not yet realized them, can one not be appalled by this?

One's investigations into Dhyana wherein one looks into the hwa-tou and brings the sentiment of doubt to bear absolutely cannot be given short shrift. [This is a case of] the so-called, "A little doubt,-- a little enlightenment. A big doubt,-- a big enlightenment. Refraining from doubt,-- one doesn't become enlightened." It is only essential that one become skillful in the use of the sentiment of doubt. If one achieves a breakthrough through the sentiment of doubt then in a single pass one can string together all of the buddhas and bodhisattvas by their noses.

It's only necessary that, for instance when one looks into the mindfulness-of-the-buddha gung-an, one simply investigates into who it is that is being mindful of the buddha. It is not the case that one is supposed to entertain doubts about who the buddha is. If it were a case of doubting who the buddha is, then it would only be necessary to listen to the lecturer say, "Amitabha is named 'Limitless Light'." After something like this then one should become enlightened and then make up a few verses on "Limitless Light." If instances such as this could be referred to as "awakening to the Way," then those with enlightened minds would be as numerous as sesame seeds and rice grains. How very sad! How very sad!

The ancients spoke of the hwa-tou as like a tile used to knock on the door. If one succeeds in opening the door by knocking, then one is supposed to go see the person in the room. It's not supposed to be the case that one stands outside the door fooling around.(3) From this one can see that in relying on the hwa-tou to bring up doubt, the doubt is not directed towards the hwa-tou. It must be directed at the very root [of the matter].

Just take for instance when Jya Shan went to visit "Boatman" who inquired of him, saying, "I've hung down the line a thousand feet. The mind abides in a deep pool, three inches from the hook. Why don't you speak?!"

Shan then started to open his mouth. The Master then knocked him into the water with an oar. Shan then climbed back into the boat. The Master said again, "Speak! Speak!" Shan was about to open his mouth again when the Master hit him again. Shan then experienced a major awakening whereupon he then knodded his head three times.

The Master then said, "The line from my fishing pole has succeeded in playing you in. Without having to stir up the purity as waves, your mind is naturally evident."

If this Jya Shan had just fooled around with the hook and line, how could "Boatman," even at the expense of a life, have been able to succeed in getting him?

This demonstrates the keen facility of the ancients in skillfully pursuing the means of bringing forth personages. In the past when the way of dhyana was flourishing, there were clear-eyed knowing advisors everywhere and the patch-robed men who were about in the land pursuing their investigations were many. Wherever they went, it flourished.

As a comparative statement, one can say that [nowadays] either there are no [practitioners of] dhyana or there are no Masters available.(4) The house of Dhyana has been silent and deserted now for a long time. How fortunate then that all at once there are many who have decided to take up the search. Although there do exist some knowing advisors, sometimes in taking the measure of the prospective candidates, those of [only] provisional talents [are allowed to] enter in as they yield to sentiment in their proffering of the seal of realization. The students, though of only shallow mind, then have the opinion that they have [actually] gotten some realizations.

Moreover, they do not have faith in the Thus Come One's sacred teachings and do not seek out the origin of the true and correct road. They only care to go on about their dull-witted doings and so it then just becomes a case of a chop made of wintermelon being taken as the real formula.(5) Not only is this a fooling of oneself, but it's also a fooling of others. Can one not be appalled by this? What's more take for example the layman Dzai Gwan who of old recorded [one of the] records of the transmitting of the lamp. There were a number of [noteworthy] men in there, but that's all.

Now, there are those people who are immersed in the weariness of the sense objects and who don't even cultivate the most obvious precepts. They have such turbid and tangled false thinking that they lean on their own clever-wittedness, scan a few cases of the ancient virtuous ones and their prospective [lineage heirs], and then in every case they presume the airs of those of the most superior faculties. As soon as they see a member of the Sangha they then harass him with verbal swordplay and then take it that they themselves have awakened to the Way. I bring this up even though we are in an age which has become corrupt especially on account of my own disciples. It can become a case of a single blind man leading on a crowd of blind people, that's all. This old man now faithfully sets forth the essential points of the true and correct meditative skills of the buddhas and patriarchs. Everyone can evaluate this. Those lofty and clear eminences who have well understood these things may themselves have ways in which they might correct it.

End Notes

1. This is a reference to Shakyamuni Buddha. See DFB, 2058c.

2. It is as yet unclear how much of the above "quote" is paraphrase.

3. This "dzwo hwo-ji" which I have translated as "to fool around" means "to knit" or "to carry on a livelihood." It's use seems a little ambiguous here.

4. This sentence is ambiguous in the Chinese and hence tentative in the English.

5. This is another utterly ambiguous Chinese sentence resulting in a tentative translation.

Maxims of Master Han Shan

PDF: The Autobiography and Maxims of Han Shan

Translated by Upasaka Richard Cheung

1. When we preach the Dharma to those who see only the ego’s illusory world, we preach in vain. We might as well preach to the dead.

How foolish are they who turn away from what is real and true and lasting and instead pursue the fleeting shapes of the physical world, shapes that are mere reflections in the ego’s mirror. Not caring to peer beneath the surfaces, deluded beings are content to snatch at images. They think that the material world’s ever-flowing energy can be modified into permanent forms, that they can name and value these forms, and then, like great lords, exert dominion over them.

Material things are like dead things and the ego cannot vivify them. As the great lord is by his very identity attached to his kingdom, the ego, when it attaches itself to material objects, presides over a realm of the dead. The Dharma is for the living. The permanent cannot abide in the ephemeral. True and lasting joy can’t be found in the ego’s world of changing illusion. No one can drink the water of a mirage.

2. There are also those who, claiming enlightenment, insist that they understand the non-substantial nature of reality. Boasting that the disease of materialism cannot infect them, they try to prove their immunity by carefully shunning all earthly enjoyments. But they, too, are in the dark.

3. Neither are they correct who dedicate themselves to exposing the fraud of every sensory object they encounter. True, perceptions of material objects give rise to wild desire in the heart. True, once it is understood how essentially worthless such apparent objects are, wild desires are reduced to timid thoughts. But we may not limit our spiritual practice to the discipline of dispelling illusion. There is more to the Dharma than understanding the nature of reality.

4. What is the best way to sever our attachment to material things?

First, we need a good sharp sword, a sword of discrimination, one that cuts through appearance to expose the real. We begin by making a point of noticing how quickly we became dissatisfied with material things and how soon our sensory pleasures also fade into discontent. With persistent awareness we sharpen and hone this sword. Before long, we find that we seldom have to use it. We’ve cut down all old desires and new ones don’t dare to bother us.

5. True Dharma seekers who live in the world use their daily activity as a polishing tool. Outwardly they may appear to be very busy, like flint striking steel, making sparks everywhere. But inwardly they silently grow. For although they may be working very hard, they are working for the sake of the work and not for the profits it will bring them. Unattached to the results of their labor, they transcend the frenetic to reach the Way’s essential tranquillity. Doesn’t a rough and tumbling stream also sparkle like striking flints – while it polishes into smoothness every stone in its path?

6. In the ego’s world of illusion, all things are in flux. But continuous change is constant chaos. When the ego sees itself as the center of so much swirling activity, it cannot experience cosmic harmony.