ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

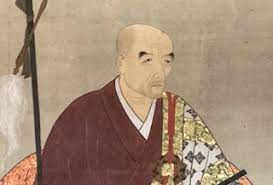

愚堂東寔 Gudō Tōshoku (1577–1661)

愚堂東寔像 白隠慧鶴筆

江戸時代(18世紀) 京都・慧照院

Portraits of Gudō Tōshoku painted by 白隠慧鶴 Hakuin Ekaku (1686-1769)

PDF: Gudō’s Lingering Radiance (Hōkan Ishō)

In: PDF: Complete Poison Blossoms from a Thicket of Thorn: The Zen Records of Hakuin Ekaku

by Hakuin Zenji, tr. by Norman Waddell

pp. 1016-1057.

愚堂東寔像 自賛

江戸時代 慶安2年(1649) 岐阜・慈溪寺

愚堂東寔 Gudō Tōshoku (1577–1661) was a Japanese Rinzai school zen monk from the early Tokugawa period. He was a leading figure in the Ōtōkan lineage of the Myōshin-ji, where he led a reform movement to revitalize the practice of Rinzai. He served three times as abbot of Myōshin-ji. Among his leading disciples was Shidō Bunan (1603–1676), from whose line came the great reformer Hakuin Ekaku (1685–1768). The illustrious Zen preacher Bankei Yōtaku earlier in life wanted to meet Gudō and receive confirmation of enlightenment, but narrowly missed seeing him at his Daisen-ji temple in Mino province (today's Gifu prefecture) because the master was visiting up in Edo (Tokyo). Gudō received the posthumous title Daien Hôkan Kokushi. He left no written words.

Bunan's Dharma Lineage

[...]

菩提達磨 Bodhidharma, Putidamo (Bodaidaruma ?-532/5)

大祖慧可 Dazu Huike (Taiso Eka 487-593)

鑑智僧璨 Jianzhi Sengcan (Kanchi Sōsan ?-606)

大毉道信 Dayi Daoxin (Daii Dōshin 580-651)

大滿弘忍 Daman Hongren (Daiman Kōnin 601-674)

大鑑慧能 Dajian Huineng (Daikan Enō 638-713)

南嶽懷讓 Nanyue Huairang (Nangaku Ejō 677-744)

馬祖道一 Mazu Daoyi (Baso Dōitsu 709-788)

百丈懷海 Baizhang Huaihai (Hyakujō Ekai 750-814)

黃蘗希運 Huangbo Xiyun (Ōbaku Kiun ?-850)

臨濟義玄 Linji Yixuan (Rinzai Gigen ?-866)

興化存獎 Xinghua Cunjiang (Kōke Zonshō 830-888)

南院慧顒 Nanyuan Huiyong (Nan'in Egyō ?-952)

風穴延沼 Fengxue Yanzhao (Fuketsu Enshō 896-973)

首山省念 Shoushan Shengnian (Shuzan Shōnen 926-993)

汾陽善昭 Fenyang Shanzhao (Fun'yo Zenshō 947-1024)

石霜/慈明 楚圓 Shishuang/Ciming Chuyuan (Sekisō/Jimei Soen 986-1039)

楊岐方會 Yangqi Fanghui (Yōgi Hōe 992-1049)

白雲守端 Baiyun Shouduan (Hakuun Shutan 1025-1072)

五祖法演 Wuzu Fayan (Goso Hōen 1024-1104)

圜悟克勤 Yuanwu Keqin (Engo Kokugon 1063-1135)

虎丘紹隆 Huqiu Shaolong (Kukyū Jōryū 1077-1136)

應庵曇華 Yingan Tanhua (Ōan Donge 1103-1163)

密庵咸傑 Mian Xianjie (Mittan Kanketsu 1118-1186)

松源崇岳 Songyuan Chongyue (Shōgen Sūgaku 1132-1202)

運庵普巖 Yunan Puyan (Un'an Fugan 1156–1226)

虛堂智愚 Xutang Zhiyu (Kidō Chigu 1185–1269)

南浦紹明 Nampo Jōmyō (1235-1308) [大應國師 Daiō Kokushi]

宗峰妙超 Shūhō Myōchō (1282-1337) [大燈國師 Daitō Kokushi

關山慧玄 Kanzan Egen (1277-1360) [無相大師 Musō Daishi]

授翁宗弼 Juō Sōhitsu (1296-1380)

無因宗因 Muin Sōin (1326-1410)

日峰宗舜 Nippō Shōshun (1367-1448)

義天玄詔 Giten Genshō

雪江宗深 Sekkō Sōshin (1408–1486)

東陽英朝 Tōyō Eichō (1428-1504) > 禪林句集 Zenrin-kushū

大雅耑匡 Taiga Tankyō (?–1518)

功甫玄勳 Kōho Genkun (?–1524)

先照瑞初 Senshō Zuisho

以安智泰 Ian Chisatsu (1514–1587)

東漸宗震 Tōzen Sōshin (1532–1602)

庸山景庸 Yōzan Keiyō (1559–1629)

愚堂東寔 Gudō Tōshoku (1577–1661)

GUDO TOSHOKU

Richard Bryan McDaniel: Zen Masters of Japan. The Second Step East. Rutland, Vermont: Tuttle Publishing, 2013.

Myoshinji, the modest temple originally built by Kanzan, evolved over time into a Kyoto complex and became the largest school in the Rinzai tradition. At the beginning of the Edo Period, its most significant abbot was Gudo Toshoku. He entered religious life at the age of eight and, as a young man, traveled about Japan visiting several Rinzai temples. He attained awakening in 1628 and his understanding of Zen was so well respected that he became the private teacher of the retired emperor, Go-Yozei, as a result of which he was given the posthumous title of Kokushi.

The most famous preserved dialogue between the emperor and the Zen master is probably a combination of several conversations. It begins with Go-Yozei saying, “It is my understanding that according to the teachings of Zen this very mind, just as it is, is Buddha. Is that correct?”

“If I agree with what you say,” Gudo responded, “your majesty will believe you understand without actually doing so. However, if I deny what you say, I will be denying something well known to all.”

“Then tell me,” the retired emperor persisted, “a man who comes to enlightenment—what happens to him after he dies?”

“I don’t know,” Gudo admitted.

“You don’t know? Aren’t you an enlightened teacher?”

“I am. But not a dead one,” Gudo pointed out.

The emperor was stymied for a moment, unsure how to proceed. Just before he started to speak again, Gudo brought his hand down hard on the wooden floor and the sound brought the emperor to awakening.

With imperial support, Gudo was able to travel throughout the Japanese isles restoring and founding temples. He served three separate terms as abbot of Myoshinji. Towards the end of his life, he settled at a small temple in Kyoto. There he is said to have reflected back on his life’s activity and remarked: “After all these years of journeying about, here I am knocking at the gates of Zen. I have to laugh. My staff is broken; my umbrella torn. And the teaching of the Buddha is so simple: when hungry, eat; when thirsty, drink; when cold, wrap yourself in a good warm cloak.”

Gudo left few written records behind, but a story is told which demonstrates the respect with which he was held. According to the tale, as an old man he still gave talks to the retired Emperor and members of his court. On one occasion, the elderly Zen master dozed off in the middle of his sermon. Rather than wake him, the emperor signaled everyone to stand quietly and leave, allowing the venerable teacher to rest undisturbed.

Just before he died, Gudo wrote: “My task is done. Now those who follow me must work for the benefit of all humankind.” After writing these words, he laid his brush down, yawned, and passed away.

愚堂東寔遺墨選

大圓寶鑑國師350年遠諱記念

花園大学歴史博物館開館10周年記念

愚堂東寔遺墨選

http://www.hanazono.ac.jp/event/20100826-2183.html

庸山景庸墨蹟 「愚堂」道号

江戸時代 慶長15年(1610) 三重・中山寺

愚堂東寔墨蹟 生死事大無常迅速

江戸時代(17世紀) 京都・華山寺

愚堂東寔墨蹟 「泰翁」道号

江戸時代 正保4年(1647) 岐阜・大仙寺