ZEN IRODALOM ZEN LITERATURE

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

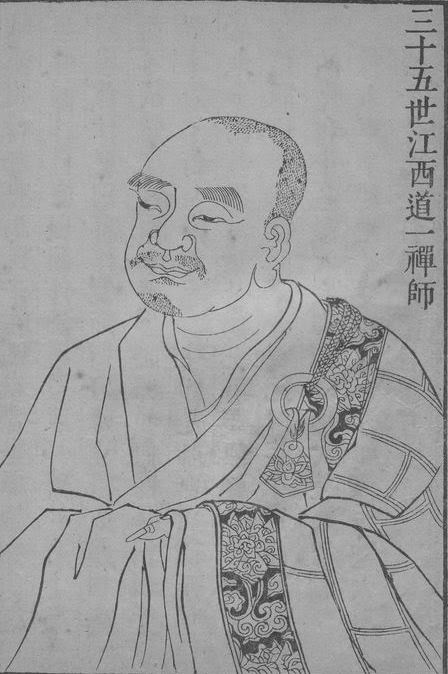

江西道一 Jiangxi Daoyi (709-788)

江西馬祖道一禪師語錄 Jiangxi Mazu Daoyi chanshi yulu; 馬祖語錄 Mazu yulu

(Rōmaji:) Kōsei Baso Dōitsu zenji goroku

(English:) Record of the Sayings of Chan Master Mazu Daoyi of Jiangsi

(Magyar:) Csiang-hszi Tao-ji: Feljegyzések Ma-curól

四家語錄 Sijia yulu (Records of Sayings of the Four Masters)

The Sijia yulu, attributed to Huanglong Huinan 黃龍慧南 (1002-1069), compiled in 1085, basically excerpts from the Guangdeng lu, its sections on the “four masters,” Mazu, Baizhang, Huangbo, and Linji.

Tartalom |

Contents |

Ma-cu Tao-ji összegyűjtött mondásaiból Macu Taoji zen tanításai

|

PDF: Ordinary Mind as the Way PDF: The Records of Mazu and the Making of Classical Chan Literature PDF: Mazu yulu and the Creation of the Chan Records of Sayings Poceski, Mario. “Mazu Daoyi.” Brill's Encyclopedia of Buddhism (Vol. 2, “Lives”). Leiden: Brill, 2019: 722–26. PDF: Sun-Face Buddha > 2nd version

PDF: Ch'an Master Ma Tsu PDF: The Hongzhou School of Chan Buddhism by Jinhua Jia PDF: Ma-tsu Tao-i and the unfolding of southern Zen The “Lost” Fragments of Mazu Daoyi in the Zongjing lu The Mind Is the Buddha Encounter Dialogues and Discourses of Mazu Daoyi The Zen Teachings of Mazu Mondo by Baso (Ma-tsu) Ma-tsu Tao-i PDF: Master Ma's ordinary mind: the sayings of Zen Master Mazu Daoyi |

![]()

Ma-cu Tao-ji összegyűjtött mondásaiból

Fordította: Terebess Gábor

A Kőrösi Csoma Sándor Intézet Közleményei, 1976. 1-2. szám, 79-83. oldal

Vö.: Folyik a híd, Officina Nova, Budapest, 1990, 18-23. oldal

A legenda szerint Pradzsnyátára, a 27. indiai pátriárka azt jövendölte, hogy Huaj-zsang mester lába alól egy csikó vágtat elő, és letiporja az egész világot. A jóslatot Huaj-zsang (677-744) egyetlen dharma-utódára, a Csianghszi tartományban tanító Tao-ji csan mesterre vonatkoztatták, mert eredeti családneve Ma volt. „Ma-cu" annyit jelent: „Ló pátriárka". Nemigen van rá példa, hogy egy buddhista szerzetes megtartsa a családnevét, még kevésbé, hogy a Huj-nenggel (638-713) megszűnt pátriárka rendszer óta egy mestert pátriárkaként tiszteljenek. De Ma-cu – minden idők egyik legnagyobb csan mestere – kivételes egyéniség volt. Kortársai már megjelenését is lenyűgőzőnek találták: „járása, mint a marháé, pillantása, mint tigrisé" – jegyezték fel róla. Tanítási módszereiben a botütés, rúgás, orrcsavarás, ordítás váltakozott a szelíd megjegyzésekkel, képtelen kijelentésekkel és talányos gesztusokkal.

Életéről keveset tudunk. Nancsouban született. Húszéves korában már szerzetes. A Heng-hegyen remetéskedett, amikor Huaj-zsang csan mester rátalált; tíz éven át oktatta, végül egyetlen dharma-örökösének ismerte el. Ma-cu ezután vándorútra indult, főleg Csianghszi tartományba és környékére. A Ta-li időszakban (766-779) telepedett le a Kaj-jüan templomban, Hungcsouban. Híre rohamosan nőtt, özönlöttek hozzá a tanítványok; csak dharma-utódainak száma is 139-re rúg, többre, mint bármelyik mesternek a csan történetében. Tőle és korának másik nagy mesterétől, Si-toutól (700-790) származtatja magát valamennyi későbbi csan és zen mester. „Csianghszi tartományban Ta-csi (=Ma-cu) volt a mester, Hunan tartományban Si-tou. Jöttek-mentek az emberek egyiktől a másikig minden időben, s aki soha nem találkozott ezzel a két nagy mesterrel, teljesen műveletlennek számított" – írta egy korabeli krónikás.

Hírneve tetőpontján Ma-cu hazalátogatott szülőfalujába. A földijei melegen ünnepelték, csak néhai szomszédja, egy öregasszony zsörtölődött: „Azt hittem, valami kivételes személyiség miatt van ilyen felfordulás, de ez csak a Ma szemetesék kölyke."

Posztumusz címét – Ta-csi (=Nagy Csend) csan mester – Hszien-cung császár adományozta 813-ban.

Ma-cu remetekunyhójában élt a Heng-hegyen, és éjt-nap belemerült az elmélkedésbe. Fel se nézett, amikor Huaj-zsang [Nan-jüe Huaj-zsang, 677-744] mester meglátogatta.

– Miért elmélkedsz? – kérdezte a mester.

– Hogy Buddha legyek – felelte Ma-cu.

Huaj-zsang felvett egy téglát, s az ajtó előtt csiszolni kezdte egy kövön.

– Mit csinálsz?

– Tükröt csiszolok.

– Hiába csiszolod, attól nem lesz tükör a tégla!

– Hiába elmélkedsz, attól nem leszel Buddha! – vágott vissza Huaj-zsang.

– Akkor mit tegyek?

– Ha nem indul el az ökrös szekér, az ökörre kell suhintani vagy a szekérre?

Ta-mej (=

„Nagy Szilva") fölkereste egy nap Ma-cut és megkérdezte tőle, mi a Buddha.

– Az értelem, az a Buddha – felelte Macu. Ta-mej megvilágosult és útra kelt, hogy egy lakható hegységet keressen magának. Mihelyt Ma-cu értesült a hollétéről, utánaküldött egy szerzetest, hogy próbára tegye.

– Mit tanultál a nagy Ma mestertől? – kérdezte a küldönc.

– A mester azt mondta nekem:

„Az értelem, az a Buddha."

– Újabban a nagy mester változtatott a tanításán.

– Hogyan?

– Most azt mondja:

„Az értelem, ami a Buddha, nem is értelem, nem is Buddha!"

– Meddig viszi még tévútra az embereket az a vén szemfényvesztő? – hördült fel Ta Mej. – Csak hadd fújja a

„nem is értelem, nem is Buddhá"-t, én maradok

„az értelem, az a Buddhá"-nál.

A szerzetes beszámolt Ma-cunak Ta-mej konokságáról.

– Érett a szilva! – ismerte el a mester.

– Miért állítod te azt – kérdezte egy szerzetes Ma-cutól –, hogy az értelem az a Buddha?

– Hogy a porontyok abbahagyják a sírást.

– És ha abbahagyták?

– Akkor azt mondom, hogy az értelem tulajdonképp nem is értelem, nem is Buddha.

– És mit mondasz annak, aki nem sorolható se ide, se oda?

– Hogy egyéb sem!

– És ha netán olyan emberre bukkansz, aki nem kötődik az egyébhez sem?

– Csak annyit mondok neki, igazodjon a Nagy Úthoz.

– Hogy igazodjunk az Úthoz? – kérdezte egy másik szerzetes.

– Én nem igazodom – jelentette ki Ma-cu.

– Honnan jöttél? – kérdezett egy szerzetest Ma-cu.

– Hunan tartományból.

– Tele van vízzel a Keleti-tó?

– Még nincs.

– Pedig milyen régóta esik – tűnődött Ma-cu. – Igazán megtelhetne már.

Egyszer egy szerzetes egy hosszú és három rövid vonalat húzott Ma-cu lába elé:

– A négy vonal közül az egyik hosszú, a másik három rövid – közölte a szerzetes –, mit tudsz még hozzátenni?

Ma-cu is húzott egy vonalat a földre:

– Ezt mondhatod hosszúnak is, mondhatod rövidnek is – mutatott rá. – Ez a válaszom.

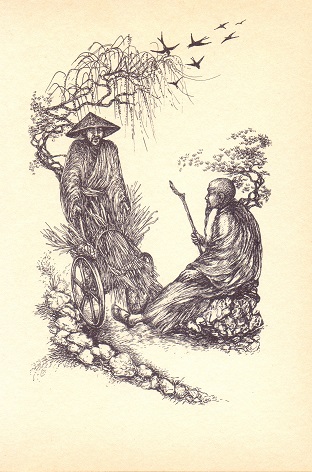

Lacza Márta illusztrációja

A mester az út szélén üldögélt és a lábát nyújtóztatta. Tanítványa, Jin-feng arra tolt egy kordét, és kérte szépen, hogy húzza be a lábát.

– Amit egyszer kinyújtok, azt vissza nem húzom! – makacsolta meg magát Ma-cu.

– Ha én egyszer nekiindultam, vissza nem fordulok! – viszonozta Jin-feng, és kordéstul átgázolt a mester lábán.

Kisvártatva Ma-cu bárddal viharzott be a csarnokkapun:

– Jöjjön elő, aki megsebezte a lábam! – zengett a hangja.

Jin-feng előlépett, lehajtotta a fejét, a mester pedig letette a bárdot.

– Mit szólsz a vízhez – kérdezte Pang Jün [740-808] –, nincs se izma, se csontja, mégis elbír tízezer tonnás hajókat.

– Itt nincs se víz, se hajó – figyelmeztette Ma-cu. – Miféle izomról és csontról locsogsz?

– Miért jött ide nyugatról Bódhidharma? – kérdezte egy szerzetes.

– Miért épp most? – érdeklődött Ma-cu.

– Miért jött ide nyugatról Bódhidharma? – kérdezte egy szerzetes.

Ma-cu rásújtott a botjával:

– Ha nem ütnélek – mentegetőzött, mindenki kiröhögne.

Suj-liao is megkérdezte Ma-cutól, miért jött ide nyugatról Bódhidharma.

Ma-cu egy hatalmas rúgással a földre terítette, és csodák csodája, Suj-liao előtt hirtelen megvilágosodott minden. Feltápászkodott, összecsapta a tenyerét és kitört belőle a nevetés:

– Csodálatos! – örvendezett. – Csodálatos! A számos elmélyülés és a számtalan felismerés egy hajszálon múlik.

Még évek múltán is mondogatta tanítványainak:

– Ma-cu förúgott egyszer és azóta egyfolytában kacagok.

– Honnan jöttél? – kérdezte Si-tou [Si-tou Hszi-csien, 700-790] egy most érkezett szerzetestől.

– Csianghsziből.

– Láttad a nagy Ma-cu mestert?

– Láttam.

Si-tou egy farönkre mutatott:

– Milyen Ma-cu ehhez képest?

A szerzetes nem felelt. Visszatért Ma-cu mesterhez és elmesélte neki, mi történt.

– Láttad, mekkora rönk volt? – kérdezte a mester.

– Hatalmas – mondta a szerzetes.

– Nahát, ilyen bivalyerős vagy?

– Hogyhogy?

– Nem kis dolog Nanjüeből idáig cipelni egy akkora rönköt.

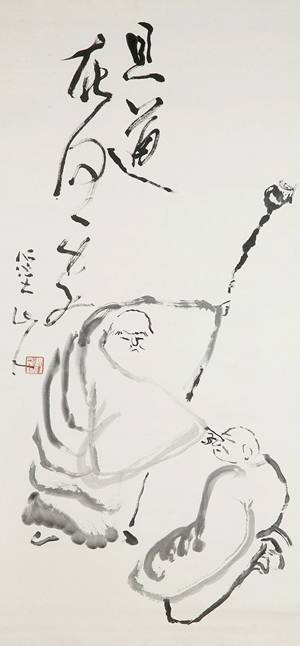

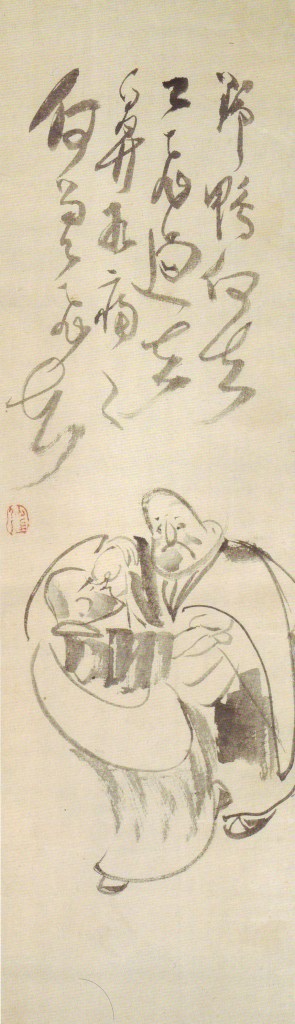

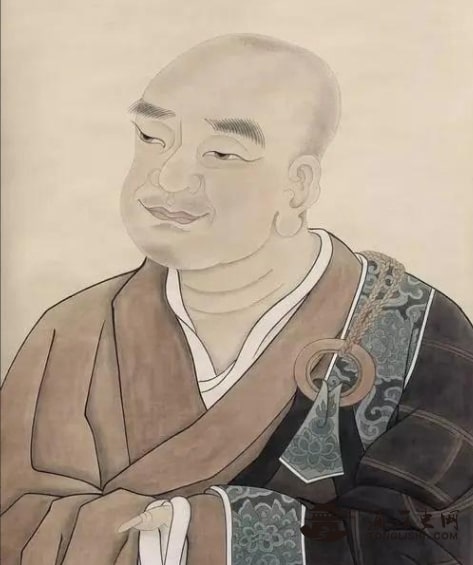

Tomita Keisen 富田渓仙 (1879-1936) és 仙厓義梵 Sengai Gibon (1750-1837) illusztrációja

Tarnóczy Zoltán illusztrációja

Pierre Székely Péter: Marhabőr faliszőnyege

Alighogy sétára indultak, mester és tanítványa, vadludak szálltak el a fejük felett.

– Mik ezek? – kérdezte Ma-cu.

– Vadlibák – nézett föl Paj-csang.

– Merre szállnak?

– Már elhúztak!

Ma-cu megragadta és úgy megcsavarta Paj-csang orrát, hogy tanítványa felüvöltött kínjában.

–

Hogy húztak volna el?! – harsogott Ma-cu.

Paj-csang feleszmélt.

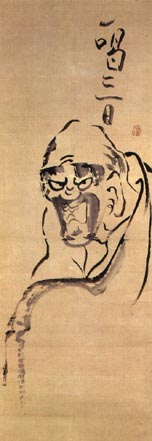

![]()

Sengai Gibon (1750-1837) tusfestménye

Ahogy Paj-csang feltűnt, Ma-cu vette a szék sarkából a légycsapóját és föltartotta.

– Ne hagyatkozz rá, ha használod! – mondta Paj-csang.

Ma-cu visszatette a légycsapót, de mielőtt Paj-csang újra szóhoz jutott volna, rákiáltott:

– Nyisd ki a szád! Beszélj csak! Majd épp attól világosulsz meg!

Paj-csang fogta a légycsapót és föltartotta.

– Ne hagyatkozz rá, ha használod! – mondta Ma-cu.

Paj-csang visszaakasztotta a légycsapót.

- KHAAAAT! – bőgte el magát Ma-cu úgy, hogy tanítványa három napra belesüketült.

– Milyen eszmékre tanítod majd az embereket? – kérdezte Ma-cu Paj-csangtól.

Paj-csang szó nélkül föltartotta a légycsapóját.

– Ez minden?

Paj-csang földhöz vágta a légycsapót.

Tarnóczy Zoltán illusztrációja

Zensho W. Kopp illusztrációja

Egyszer a három tanítvány, Nan-csüan, Hszi-tang és Paj-csang elkísérte Ma-cu mestert egy holdfényes sétára.

– Mit gondoltok – kérdezte Ma-cu –, mire lehetne legjobban kihasználni ezt az időt?

– A szövegek tanulmányozására – szólalt meg elsőnek Hszi-tang.

– Kiváló alkalom az elmélkedésre – javasolta Paj-csang.

Ilyen válaszok hallatán Nan-csüan megfordult, és faképnél hagyta őket.

– A szövegeket meghagyom Hszi-tangnak – mondotta a mester –, Paj-csang pedig valóban tehetséges elmélkedő. De Nan-csüan lépett túl a hívságokon.

Ma-cu megbetegedett egyszer és a szerzetesfelügyelő a hogyléte felől érdeklődött.

– Naparcú Buddha, holdarcú Buddha - válaszolt Ma-cu.

Macu Taoji zen tanításai

Fordította: Hadházi Zsolt

Forrás: The Zen Teachings of Mazu. Translated by Thomas Cleary

A hétköznapi tudat

Az Út nem igényel gyakorlást, csak ne szennyezd be. Mi a szenny? Míg ingadozó tudatod van, ami kitalációkat és agyalásokat hoz létre, az mind szenny. Ha az Utat közvetlenül akarod megérteni, a hétköznapi tudat az Út. A hétköznapi tudat alatt azt a tudatot értem, amiben nincs kitaláció, nincs személyes ítélet, nincs megragadás, vagy elutasítás.

A gyökér

A zen alapítói azt mondták, hogy az ember lényege önmagában teljes. Csak ne időzz jó, vagy rossz dolgok felett – ezt nevezik az Út gyakorlásának. Megragadni a jót és elutasítani a rosszat, az ürességet szemlélni és belépni az összeszedettségbe, ez mind a kitalációk tartománya – és ha külsőségek után kutatsz, egyre messzebb és messzebb távolodsz el. Csak hagyd abba a világ gondolati tárgyiasítását. A kalandozó tudat egyetlen gondolata a gyökere a születésnek és halálnak ebben a világban. Csak ne legyen semmilyen gondolatod és megszabadulsz a születés és halál gyökerétől.

A tengeri elmélkedés

Időtlen idők óta az emberi káprázatok, a megtévesztés, a büszkeség, a fondorlatosság és az önhittség egyetlen egy testben gyűltek össze. Ezért mondja az írás, hogy ez a test csak elemekből áll és a megjelenése és eltűnése csak az elemeké, miknek nincs személyiségük. Mikor az egymást követő gondolatok nem várják be a másikat, s mindegyik gondolat békésen elhal, ezt hívják a tengeri elmélkedésben való elmélyülésnek.

Megtévesztés és megvilágosodás

A megtévesztés azt jelenti, hogy nem vagy tudatában saját eredendő tudatodnak; a megvilágosodás azt jelenti, hogy felismered saját eredendő lényegedet. Egyszer megvilágosodsz, s onnantól soha többé nem leszel megtévesztve. Ha megérted a tudatot és a tárgyakat, akkor nem jelennek meg hamis felfogások; mikor nem jelennek meg hamis felfogások, ez az elfogadása a dolgok kezdetnélküliségének. Mindig is megvolt neked, s most is megvan – nincs szükség az Út gyakorlására és meditációban ülésre.

A Tao

Ez a pillanat, ahogy sétálsz, állsz, ülsz és fekszel, válaszolsz minden helyzetre és viselkedsz az emberekkel – ez mind a Tao. A Tao a valóság birodalma. Nem számít mennyiek a megszámlálhatatlan és felfoghatatlan működések, nincsenek túl ezen a birodalmon. Ha túl lennének, hogyan beszélhetnénk a Tudat-földről, s hogyan szólhatnánk a kifogyhatatlan lámpásról?

A tudat

Minden jelenség tudati; minden megnevezést a tudat nevez meg. Minden jelenség a tudatból jelenik meg; a tudat a gyökere minden jelenségnek. Egy szútra azt mondja: „Mikor ismered a tudatot és megérkezel a gyökérforrásához, abban az értelemben vallásosnak lehet téged nevezni.”

A dharmakája

A dharmakája végtelen; nem növekszik és nem csökken. Hatalmas lehet, vagy picurka; durva, vagy sima; képeket jelenít meg a dolgokkal és a lényekkel összhangban, miként a hold tükröződik egy tócsában. Működése kiárad, mégsem ver gyökeret; sosem meríti ki a szándékos tetteket, de nem is időzik tétlenségben. A szándékos tett a hitelesség működése; a hitelesség a szándékos tett alapja. Ha már valaki nincs többé rögződve ehhez az alaphoz, arról, az üres térhez hasonlóan, önállóként beszélnek.

Olyanság

A tudat valódi olyansága hasonló a tükörhöz, ami tükrözi az alakokat: a tudat olyan, mint a tükör, és a jelenségek olyanok, mint a (tükrözött) alakok. Ha a tudat megragadja a jelenségeket, akkor belevonja magát a külső feltételekbe és okokba; ezt jelenti a „tudat születése és halála”. Ha nem ragad meg ilyen jelenségeken, ez az, amit a „tudat valódi olyansága” jelent.

Az összes dharma a buddhista tanítások; az összes dharma a megszabadulás. A megszabadulás a valódi olyanság, és semmi sem különálló ettől a valódi olyanságtól. Sétálás, állás, ülés és fekvés mind felfoghatatlan cselekedetek.

Fordítási példa

[Astus = Hadházi Zsolt]

http://dharma.blog.hu/2011/03/13/forditasi_peldaNem mindegy, hogy milyen egy fordítás. A legtöbb esetben nem az szokott a gond lenni, hogy a fordító nem ismeri a nyelvet eléggé (bár ilyen is megtörténik), hanem az, hogy az adott témakörben mennyire jártas, illetve ő maga milyen értelmezést részesít előnyben. Egy szövegnek többféle fordítása is lehet nyelvileg helyes, miközben a végeredmények különböző szemléleteket tükrözhetnek. Az ember könnyen megfeledkezhet arról, hogy amit olvas, az egy fordítás, így a szöveg alaposabb értelmezéséhez szükség van a forrás ismeretére is. Másrészt, amennyiben valaki jártas az adott témakörben, könnyebben visszafejti, hogy egy-egy kifejezés pontosan mire utal.

A következőkben mutatok egy példát, hogy a következő történetet ki és hogyan fordította. Itt az elején a saját fordításom szerepel, amit az első kínai szövegből (YL) készítettem, a többi forrását a végén adom meg. A történetet magát négy különböző kínai forrásból adom meg, hogy látható legyen, mit jelen az "eredeti" változat.

- Tisztelendő, miért mondja, hogy ez a tudat a buddha? - kérdezte egy szerzetes.

- Hogy a gyerek abbahagyja a sírást. - mondta Mazu.

- És amikor abbahagyta a sírást?

- Sem tudat, sem buddha. - mondta Mazu.

- És ha egy olyan emberrel találkozik, aki mindkettőt elhagyta, akkor mit tanít?

- Megmondom neki, hogy az nem egy dolog. - mondta Mazu.

- És mi van akkor, ha hirtelen valaki olyannal találkozik, aki már ott van?

- Akkor azt tanítom neki, hogy tapasztalja meg a Nagy Utat. - mondta Mazu.YL: 僧問。和尚為甚麼說即心即佛。

TJ: 有僧問云。和尚為什麼說即心即佛。

CDL: 僧問。和尚為什麼說即心即佛。

ZT: 僧問馬祖。和尚為甚麼說即心即佛。

TG: Miért állítod te azt – kérdezte egy szerzetes Ma-cutól –, hogy az értelem az a Buddha?

TC: A monk asked: "Why do you teach that Mind is no other than Buddha?"

CCB: A monk asked, "Why does the Venerable say that mind is Buddha?"

MP: A monk asked, “Why does the Reverend say that mind is Buddha?”

PH: A monk once asked him why he taught "presend mind is Buddha."

AF: A monk asked, "Master, why do you say that mind is Buddha?"

YL: 祖曰。為止小兒啼。

TJ: 祖曰。為止小兒啼。

CDL: 師云。為止小兒啼。

ZT: 曰為止小兒啼。

TG: Hogy a porontyok abbahagyják a sírást.

TC: "In order to make a child stop its crying."

CCB: The Patriarch said, "To stop small children's crying."

MP: Mazu said, “To stop small children's crying.”

PH: Mazu said, "To stop the crying of small children."

AF: Mazu said, "To stop babies from crying."

YL: 曰啼止時如何。

TJ: 僧曰。啼止後如何。

CDL: 僧云。啼止時如何。

ZT: 曰啼止後如何。

TG: És ha abbahagyták?

TC: "When the crying is stopped, what would you say?"

CCB: The monk asked, "What do you say when they have stopped crying?"

MP: The monk asked, “What do you say when they have stopped crying?”

PH: The monk wanted to know, "When the crying stops, what then?"

AF: The monk said, "What do you say when they stop crying?"

YL: 祖曰。非心非佛。

TJ: 祖曰。非心非佛

CDL: 師云。非心非佛。

ZT: 曰非心非佛。

TG: Akkor azt mondom, hogy az értelem tulajdonképp nem is értelem, nem is Buddha.

TC: "Neither Mind nor Buddha."

CCB: The Patriarch said, "It is neither mind nor Buddha."

MP: Mazu said, “[I say that] it is neither mind nor Buddha (feixin feifo).”

PH: Mazu replied, "Not mind, not Buddha."

AF: Mazu said, "No mind, no Buddha."

YL: 曰除此二種人來。如何指示。

TJ: 僧曰。除此一種人來如何指示

CDL: 僧云。除此二種人來如何指示。

ZT: 曰除此二種人來。如何指示。

TG: És mit mondasz annak, aki nem sorolható se ide, se oda?

TC: "What teaching would you give to him who is not in these two groups?"

CCB: The monk asked, "And when you have someone who does not belong to either of these two, how do you instruct him?"

MP: The monk asked, “And when you have someone who does not belong to either of these two categories, how do you instruct him?”

PH: "So if someone comes along who has gone beyond these two kinds of expedients, what will you point to as the ancestral doctrine then?"

AF: The monk asked, "Without using either of these teachings, how would you instruct someone?"

YL: 祖曰。向伊道不是物。

TJ: 祖曰。向伊道。不是物。

CDL: 師云。向伊道不是物。

ZT: 曰為伊道不是物。

TG: Hogy egyéb sem!

TC: "I will say, 'It is not a something.'

CCB: The Patriarch said, "I tell him that it is not a thing."

MP: Mazu said, “I tell him that it is not a thing (bushi wu).”

PH: "Then I'd tell him, 'Not being anything.'"

AF: Mazu said, "I would say to him that it's not a thing."

YL: 曰忽遇其中人來時如何。

TJ: 曰忽遇其中人來時如何。

CDL: 僧云。忽遇其中人來時如何。

ZT: 曰忽遇其中人來時如何。

TG: És ha netán olyan emberre bukkansz, aki nem kötődik az egyébhez sem?

TC: "If you unexpectedly interview a person who is in it what would you do?" finally, asked the monk.

CCB: The monk asked, "And how about when you suddenly meet someone who is there?"

MP: The monk asked, “And how about when you suddenly meet someone who is there?”

PH: Still the monk persisted. "What if you meet someone who comes from the Middle Path?"

AF: The monk asked, "If suddenly someone who was in the midst of it came to you, then what would you do?"

YL: 祖曰。且教伊體會大道。

TJ: 祖曰。且教伊體會大道。

CDL: 師云。且教伊體會大道。

ZT: 曰且教伊體會大道。

TG: Csak annyit mondok neki, igazodjon a Nagy Úthoz.

TC: "I will let him realize the great Tao."

CCB: The Patriarch said, "I teach him to directly realize the Great Way."

MP: Mazu said, “I teach him to intuitively realize the great Way.”

PH: Mazu said, "Then I would teach him to join bodily and communicate the great Dao."

AF: Mazu said, "I would teach him to experience the great way."Források:

YL: Jiangxi mazu daoyi chanshi yulu (江西馬祖道一禪師語錄, X69n1321_p0004c19-22)

TJ: Chanzong songgu lianzhu tongji (禪宗頌古聯珠通集, X65n1295_p0524b05-09)

CDL: Jingde chuandeng lu (景德傳燈錄, T51n2076_p0246a21-25)

ZT: Lengyanjing zongtong (楞嚴經宗通, X16n0318_p0814a04-08)

TG: Terebess Gábor (https://terebess.hu/keletkultinfo/folyik.html)

TC: Thomas Cleary (http://www.abuddhistlibrary.com/Buddhism/C%20-%20Zen/Ancestors/The%20Zen%20Teachings%20of%20Mazu/The%20Zen%20Teachings%20of%20Mazu.htm)

CCB: Cheng Chien Bhikshu (Cheng Chien Bhikshu [Mario Poceski]: Sun-Face Buddha, p. 78)

MP: Mario Poceski (Mario Poceski: Ordinary Mind as the Way, p. 177)

PH: Peter Hershock (Peter D. Hershock: Chan Buddhism, p. 117-118)

AF: Andrew Ferguson (Andrew E. Ferguson: Zen's Chinese Heritage, p. 68)

Macu tanítóbeszédei¹

http://karuna.hu/letoltesek_elemek/japan/macu_tanitobeszedei.pdf

1.

A pátriárka így szólt a gyülekezethez:

- Higgyétek el, hogy tudatotok a Buddha, hogy ez a tudat azonos a Buddhával. Bódhidharma

nagymester Indiából Kínába jött és átadta a mahájána Egy Tudat tanítását, hogy az elvezessen

benneteket a felébredéshez. Attól tartván, hogy túl zavarodottak lesztek és nem fogtok hinni benne,

hogy ez az Egy Tudat eredendıen bennetek van a Lankávatára szútrát használta, hogy lepecsételje

az érzı lények tudat-talaját. Ezért a Lankávatára szútrában a tudat az összes buddha tanításának, és

a nincs kapu a Dharma-kapu.

Akik a Dharmát keresik ne keressenek semmit se.2 A tudaton kívül nincs másik Buddha, a Buddhán

kívül nincs másik tudat. Nem ragaszkodva a jóhoz és nem elutasítva a gonoszat, tisztaságra vagy

szennyezettségre támaszkodás nélkül az ember megérti, hogy a vétek természete üres, nem található

egyetlen gondolatban sem, mert öntermészet nélküli. Ezért a három birodalom csupán tudat és

minden jelenséget a világegyetemben egyetlen Dharma jellemez.3 Bármikor is látunk formát, az a

tudat látása. A tudat nem létezik önmagában, létezése a forma miatt van. Bármit is mondasz, az

csupán egy jelenség mely azonos az alapelvvel. Mind akadály nélküliek és a bódhihoz vezetı út

gyümölcse is épp ilyen. Bármi jelenjék is meg a tudatban azt formának nevezik, mikor valaki tudja,

hogy minden forma üres, akkor a születés azonos a nincs-születéssel. Ha valaki felismeri ezt a

tudatot, akkor mindig viselheti ruháját és eheti ételét. Táplálva a bölcsesség méhét az ember

természetesen tölti idejét, mi más van mit csinálni? Megkapva tanításomat figyeljetek versemre:

Mindig beszélnek a tudat-talajról,

A bódhi szintúgy csak béke.

Mikor jelenség és alapelv akadálytalan,

E születés azonos a nincs-születéssel.

2.

Egy szerezetes kérdezte:

- Mi az Út gyakorlása?

A pátriárka válaszolt:

- Az Út nem tartozik a gyakorláshoz. Ha valaki gyakorláson keresztüli megvalósításról beszél,

bármit is ért el olyanmód, még mindig visszaesésnek alávetett. Az ugyanolyan, mint a srávakák. Ha

valaki azt mondja, hogy nincs szükség gyakorlásra, az ugyanolyan, mint a hétköznapi emberek.

A szereztes ezt is kérdezte:

- Miféle megértéssel rendelkezzen valaki, hogy felfogja az Utat?

A pátriárka válaszolt:

- Az öntermészet eredendıen teljes. Ha valakit nem akadályoznak meg se jó, se rossz dolgok, akkor

az az Utat gyakorolja. Megragadni a jót és elutasítani a rosszat, a súnjatán szemlélıdni és

szamádhiba lépni; ezek mind a cselekvéshez tartoznak. Ha valaki kívül keres, eltávolodik tıle. Csak

vess véget minden tudati fogalomnak a három világban.Ha nincs egyetlen gondolat sem, akkor az

ember megsemmisítette a születés és halál gyökerét és megszerzi a Dharma király felülmúlhatatlan

kincsét.

Határtalan kalpák óta formálja meg az ember testét a megannyi világi hamis gondolkodás, [mint a]

becsvágy, ıszintétlenség, büszkeség, és az önteltség. Ezért mondja a szútra: „Csupán a megannyi

dharmák csoportosulása következtében formálódik meg a test. Mikor megjelenik, csupán dharmák

jelennek meg; mikor megszőnik, csupán dharmák szőnnek meg. Mikor a dharmák megjelennek,

1 Sun Face Buddha, trans. by Cheng Chien Bhikshu, Asian Humanities Press, 1992. pp. 62-68.

2 Vimalakírti szútra, „Mandzsúsri a betegségrıl kérdez” fejezet

3 Fajujing T85n2901_p1435a23

nem mondják, hogy én jelenek meg; mikor megszőnnek, nem mondják, hogy én szőnök meg.”4

Az elızı gondolat, a következı gondolat, és a jelen gondolat, egyik gondolat sem vár a másikra,

minden egyes gondolat nyugodt és kialudt.5 Ezt nevezik az Óceán Pecsét Szamádhinak. Minden

dharmát magában foglal. Miképpen különbözı folyamok százai és ezrei, mikor visszatérnek a nagy

óceánba, mindet az óceán vizének nevezik. [Az óceán vize] egy íző, mely minden ízt tartalmaz.6 A

nagy óceánban minden folyam összekeveredik, s mikor valaki az óceánban fürdik az összes vizet

használja.

A srávakák felébredettek, mégis tudatlanok; a hétköznapi emberek tudatlanok a felébredésrıl. A

srávakák nem tudják, hogy a Szent Tudat eredendıen mentes minden pozíciótól, októl és okozattól,

fokozatoktól, tudati fogalmaktól és hamis gondolatoktól. Okok gyakorlásával elérik a gyümölcsöt

és az üresség szamádhijában tartózkodnak húsztól nyolcvanezer kalpáig. Bár már felébredtek,

felébredésük ugyanolyan, mint a tudatlanság. Minden bódhiszattva úgy tekint erre mint a pokol

szenvedéseire, vagyis az ürességbe zuhanásra, a kialvásban tartózkodásra, hogy nem látható a

buddha-természet.

Egy kiváló képességő ember találkozhat egy erényes baráttal és útmutatásokat kaphat tıle. Ha

meghallván a szavakat megértésre jut, akkor anélkül, hogy lépéseken menne keresztül, hirtelen

felébred az eredendı természetre. Ezért mondja a szútra: „A hétköznapi emberek változhatnak, de

nem a srávakák.”7

A tudatlansággal szemben beszél valaki a felébredésrıl. Mivel eredendıen nincs tudatlanság, a

felébredést sem kell megalapozni. Minden élılény határtalan kalpák óta a Dharma-természet

szamádhijában tartózkodik. Miközben a Dharma-természet szamádhijában vannak, ruhát viselnek,

ételt esznek, beszélnek és válaszolnak a dolgokra. A hat érzékszerv használata, minden cselekvés a

Dharma-természet. Mert nem tudják, hogyan térjenek vissza a forráshoz, ezért neveket követnek és

formákat keresnek, melyekbıl zavaró érzelmek és hamisságok keletkeznek, így jönnek létre a

karma különféle változatai. Mikor az ember egyetlen gondolatban visszatekint és belülre világít,

akkor minden a Szent Tudat.

Mindannyian lássátok át saját tudatotokat, ne jegyezzétek fel szavaim. Még ha annyi alapelvrıl is

van szó, mint a Gangesz homokszemei, a tudat nem növekszik. És ha semmit sem mondanak, a

tudat nem csökken. Mikor van beszéd, az csak a saját tudatod. Mikor csend van, az még mindig a

saját tudatod. Még ha valaki különféle átalakulás testeket is lenne képes létrehozni, fénysugarakat

bocsátana ki és megjelenítené a tizennyolcféle átalakulást, az még mindig nem olyan, mint halott

hamuhoz hasonlóvá válni.

A nedves hamu erıtlen, a srávakákhoz hasonlatos, akik hamisan gyakorolják az okokat hogy elérjék

a gyümölcsöket. A száraz hami erıvel bír és a bódhiszattvákhoz hasonlatos, kiknek karmája érett és

akiket nem szennyez semmilyen gonosz. Ha valaki a Tripitaka összes ügyes eszközérıl beszélne,

melyeket a Tathágata kifejtett, még megszámlálhatatlan kalpák utány sem tudná befejezni az

egészet. Olyan mint egy végtelen lánc. De ha valaki képes felébredni a Szent Tudatra, akkor nincs

semmi más teendı. Elég sokáig álltatok. Vigyázzatok magatokra!

3.

A pátriárka így szólt a gyülekezethez:

- Az Útnak nincs szüksége gyakorlásra, csak ne szennyezzétek be. Mi a szenny? Mikor a születés és

halál tudatával valaki kigondoltan cselekszik, akkor minden szenny. Ha valaki közvetlenül akarja

ismerni az Utat, a Hétköznapi Tudat az Út. Mit jelent a Hétköznapi Tudat? Nincs cselekvés, nincs

helyes vagy rossz, nincs megragadás vagy elutasítás, sem mulandó sem állandó, világi és szent

nélküli. A szútra mondja: „Sem a hétköznapi emberek gyakorlata, sem a bölcsek gyakorlata, ez a

4 Vimalakírti szútra, „Mandzsúsri a betegségrıl kérdez” fejezet

5 Vimalakírti szútra, „Tanítványok” fejezet

6 utalás az Avatamszaka szútra „Tíz fokozat” fejezetére

7 Vimalakírti szútra, „Buddha útrja” fejezet

bódhiszattvák gyakorlata.”8 Épp mint most, akár sétálás, állás, ülés, vagy fekvés, válaszolás a

helyzetekre és foglalkozás az emberekkel ahogy jönnek: minden az Út. Az Út azonos a

dharmadhátuval. Az összes mélységes mőködés közt, mely számos mint a Gangesz homokszemei,

egy sincs a dharmadhátun kívül. Ha ez nem így volna, hogyan lehetett volna azt mondani, hogy a

tudat-talaj a Dharma-kapu, hogy az egy kimeríthetetlen lámpás?

Minden dharma tudati dharma, minden név tudati név. A tízezer dharma minde a tudatból született,

a tudat a tízezer dharma gyökere. A szútra mondja: „A tudat ismerete és az eredeti forrás átlátása

miatt hívnak valakit sramanának.” A nevek egyenlıek, a jelentések egyenlıek: minden dharma

egyenlı. Mind tiszták keveredés nélkül. Ha valaki eléri ezt a tanítást, akkor mindig szabad. Ha a

dharmadhátu megalapozódott, akkor minden a dharmadhátu. Ha az olyanság megalapozódott, akkor

minden az olyanság. Ha az alapelv megalapozódott, akkor minden dharma az alapelv. Ha a

jelenségek megalapozódottak, akkor minden dharma a jelenségek. Mikor egyet felemelnek, ezrek

követik. Az alapelv és a jelenségek nem különbözıek, minden csodálatos mőködés, és nincs másik

alapelv. Mind a tudatból jön.

Például bár a hold tükrözıdései számtalanok, az valódi hold csupán egy. Bár sok forrása van a

víznek, a víznek csupán egyetlen természete van. Tízezer jelenség van a világegyetemben, de az

üres tér csak egy. Sok alapelvrıl beszélnek, de az akadálytalan bölcsesség csak egy.9 Bármit is

alapoznak meg, mind az Egy Tudatból jön. Akár felépítés, akár elsöprés, mind a mélységes

mőködés, mind önmaga. Nem lehet olyan helyre állni, ahol az ember elhagyná az Igazságot.

Pontosan az a hely ahol áll az Igazság; az egész önmaga létezése. Ha ez nem így volna, akkor ki

volna az? Minden dharma a Buddhadharma és minden dharma a megszabadulás. A megszabadulás

aznos az olyansággal, egyetlen dharma sem hagyja el soha az olyanságot. Akár sétálás, állás, ülés,

vagy fekvés, minden mindig a felfoghatatlan mőködés. A szútrák mondják, hogy a Buddha

mindenütt ott van.

A Buddha könyörületes és bölcs. Ismerve jól minden lény természetét és jellemét, képes áttırni a

lények kételyeinek hálóját. Elhagyta a lét és semmi kötelékeit; mivel minden világi és szent érzés

kialudt, [látja, hogy] az én és a dharmák üresek. Megforgatja az összehasonlíthatatlan [Dharma]

kereket. Túlmenve számokon és mértékeken, cselekvése akadálytalan és átlátja mind az alapelveet

és a jelenségeket.

Mint egy felhı az égen mely hirtelen megjelenik és aztán eltőnik minden nyom nélkül, és mint a

vízen írás, nem született és nem megsemmisült: ez a Nagy Nirvána.

Megkötözötten tathágatagarbhának nevezik, mikor megszabadul, úgy hívják tiszta dharmakája. A

dharmakája határtalan, lényege nem növekszik vagy csökken. Hogy a lényeknek válaszoljon,

megjelenhet nagyként és kicsiként, szögletesként vagy kerekként. Olyan, mint a hold tükrözıdése a

vizen. Finoman mőködik, anélkül, hogy gyökereket alapozna meg.

Nem elpusztítva a feltételeset, nem lakozva a feltétel nélküliben.10 A feltételes a feltétlen mőködése;

a feltétlen az alapelve a feltételesnek. Mert nem lakozik támasztékon, így mondják: „mint a tér mi

semmin sem nyugszik.”11

A tudatról [két módon] lehet beszélni: születés és halál, és olyanság.12 A tudat mint olyanság olyan,

mint a tiszta tükör mely képeket tud visszatükrözni. A tükör jelképezi a tudatot; a képek jelképezik

a dharmákat. Ha a tudat megragadja a dharmákat, akkor külsıdleges okok és feltételek közé kerül,

mely a születés és halál jelentése. Ha a tudat nem ragadja meg a dharmákat, ez az olyanság.

A srávakák hallanak a buddha-természetrıl, míg a bódhiszattva szeme látja a buddha-természetet. A

nem-kettısség megértését hívják egyenl természetnek. Bár a természet mentes a

megkülönböztetéstıl, mőködése nem ugyanolyan: mikor tudatlan akkor tudatnak nevezik, mikor

felébredett akkor bölcsességnek. Az alapelv követése a felébredés, és a jelenségek követése a

tudatlanság. A tudatlanság annyi, mint nem tudni az eredendı tudatról. Felébredni annyi, mint

8 Vimalakírti szútra

9 Vimalakírti szútra: „az akadálytalan bölcsesség csak egy”

10 Vimalakírti szútra, „Bódhiszattvák gyakorlata” fejezet

11 Avatamszaka szútra, „Tathágata megjelenése” fejezet

12 utalás a Hit felébresztése c. értekezésre

felébredni az eredendő természetre. Ha egyszer felébredt, mindig felébredt marad, nincs többé

tudatlanság. Mint mikor a nap jön, minden sötétség eltőnik. Mikor a pradnyá napja felkel, nem

létezik együtt a szennyek szötétségével. Ha valaki felfogja a tudatot és a tárgyakat, akkor a hamis

gondolkodást nem hozza létre újból. Mikor nincs többé hamis gondolkodás, ez az elfogadása a

dharmák nem-keletkezésének. Eredendıen létezik és jelen van most, függetlenül az Út

gyakorlásától és a meditációban üléstıl. Nem gyakorlás és nem ülés a Tathágata tiszta meditációja.

Ha most igazán megérted a valódi jelentését ennek, akkor ne hozz létre semmilyen karmát.

Elégedetten birtokoddal, töltsd el életedet. Egy tál, egy ruha, akár ülés vagy állás, mindig veled van.

Betartva a sílát tiszta karmát halmozol. Ha ilyen tudsz lenni, hogy lehet bármi aggodalom afelıl,

hogy nem érted meg? Sokáig álltatok. Vigyázzatok magatokra

Mazu Daoyi's Dharma Lineage

[...]

菩提達磨 Bodhidharma, Putidamo (Bodaidaruma ?-532/5)

大祖慧可 Dazu Huike (Taiso Eka 487-593)

鑑智僧璨 Jianzhi Sengcan (Kanchi Sōsan ?-606)

大毉道信 Dayi Daoxin (Daii Dōshin 580-651)

大滿弘忍 Daman Hongren (Daiman Kōnin 601-674)

大鑑慧能 Dajian Huineng (Daikan Enō 638-713)

南嶽懷讓 Nanyue Huairang (Nangaku Ejō 677-744)

馬祖道一 Mazu Daoyi (Baso Dōitsu 709-788)

Ma-tsu (709-788)

Sermons

From Sun-Face Buddha: The Teachings of Ma-Tsu and the Hung-chou School of Ch'an

Asian Humanities Press, 1992.

Translated by Cheng Chien Bhikshu (aka Mario Poceski)

PDF: Sun-Face Buddha

The Patriarch said to the assembly, “All of you should believe that your mind is Buddha, that this mind is identical with Buddha. The great master Bodhidharma came from India to China, and transmitted the One Mind teaching of Mahayana so that it can lead you all to awakening. Fearing that you will be too confused and will not believe that this One Mind is inherent in all of you, he used the Lankavatara Sutra to seal the sentient beings’ mind-ground. Therefore, in the Lankavatara Sutra, mind is the essence of all the Buddha’s teachings, no gate is the Dharma-gate.

“Those who seek the Dharma should not seek for anything. Outside of mind there is no other Buddha, outside of Buddha there is no other mind. Not attaching to good and not rejecting evil without reliance on either purity or defilement, one realizes that the nature of offence is empty: it cannot be found in each thought because it is without self-nature. Therefore, the three realms are mind-only and ‘all phenomena in the universe are marked by a single Dharma.’ Whenever we see form, it is just seeing the mind. The mind does not exist by itself; its existence is due to form. "Whatever you are saying, it is just a phenomenon which is identical with the principle. They are all without obstruction and the fruit of the way to ‘bodhi’ is also like that. Whatever arises in the mind is called form; when one knows all forms to be empty, then birth is identical with no-birth. If one realizes this mind, then one can always wear one’s robes and eat one’s food. Nourishing the womb of sagehood, one spontaneously passes one’s times: what else is there to do? Having received my teaching, listen to my verse:

The mind-ground is always spoken of,

Bodhi is also just peace.

When phenonoma and the principle

Are all without obstruction,

The very birth is identical with no birth.

A monk asked, “What is the cultivation of the Way?”The Patriarch replied, “The Way does not belong to cultivation. If one speaks of any attainment through cultivation, whatever is accomplished in that way is still subject to regress.”The monk also asked, “What kind of understanding should one have in order to comprehend the Way?”The Patriarch replied, “The self-nature is originally complete. If one only does not get hindered by either good or evil things, then that is a person who cultivates the Way. Grasping good and rejecting evil, contemplating sunyata and entering Samadhi-all of these belong to activity. If one seeks outside, one goes away from it. Just put an end to all mental conceptions in the three realms. If there is not a single thought, then one eliminates the root of birth and death and obtains the unexcelled treasury of the Dharma king.“Since limitless kalpas, all worldly false thinking, such as flattery, dishonesty, self-esteem, and arrogance have formed one body. That is why the sutra says, ‘It is only through the grouping of many dharmas that this body is formed. When it arises, it is only dharmas arising; when it ceases, it is only dharmas ceasing. When the dharmas arise, they do not say I arise; when they cease, they do not say, I cease.’“The previous thought, the following thought, and the present thought, each thought does not wait for the others; each thought is calm and extinct. This is called Ocean Seal Samadhi. It contains all dharmas. Like hundreds and thousands of different streams-when they return to the great ocean, they are all called water of the ocean. The water of the ocean has one taste which contains all tastes. In the great ocean all streams are mixed together; when one bathes in the ocean, he uses all waters.“Some are awakened, and yet still ignorant; the ordinary people are ignorant about awakening. Many do not know that originally the Holy Mind is without any position, without cause and effect, without stages, mental conceptions, and false thought. By cultivating causes they attain the fruits and dwell in the Samadhi of emptiness from twenty to eighty thousand kalpas. Though already awakened, their awakening is the same as ignorance. All Bodhisattvas view this as suffering of the hells: falling into emptiness, abiding in extinction, unable to see the Buddha-nature.“There might be someone of superior capacity who meets a virtuous friend and receives instructions from him. If upon hearing the words he gains understanding, then without passing through the stages, suddenly he is awakened to the original nature. “It is in contrast to ignorance that one speaks of awakening. Since originally there is no ignorance, awakening also need not be established. All living beings have since limitless kalpas ago been abiding in the Samadhi of the Dharma-nature. While in the Samadhi of the Dharma-nature, they wear their clothes, eat their food, talk and respond to things. Making use of the six senses, all activity is the Dharma-nature. It is because of not knowing how to return to the source, that they follow names and seek forms, from which confusing emotions and falsehood arise, thereby creating various kinds of karma. When within a single thought one reflects and illuminates within, then everything is the Holy Mind.“All of you should penetrate your own minds; do not record my words. Even if principles as numerous as the sands of the Ganges are spoken of, the mind does not increase. And if nothing is said, the mind does not decrease. When there is speech, it is just your own mind. Even if one could produce various transformation bodies, emit rays of light and manifest the eighteen transmutations, that is still not like becoming like dead ashes.“If one is to speak about all expedient teachings of the tripitaka that the Tathagata has expounded, even after innumerable kalpas one still will not be able to finish them all. It is like an endless chain. But if one can awaken to the Holy Mind, then there is nothing else to do. You have been standing long enough. Take care!”The Patriarch said to the assembly, “The Way needs no cultivation, just do not defile. What is defilement? When with a mind of birth and death one acts in a contrived way, then everything is defilement. If one want to know the Way directly: Ordinary Mind is the Way! What is meant by Ordinary Mind? No activity, no right or wrong, no grasping or rejecting, neither terminable nor permanent, without worldly or holy. The sutra says, ‘Neither the practice of ordinary people, nor the practice of sages, that is the Bodhisattva’s practice.’“Just like now, whether walking, standing, sitting, or reclining, responding to situations and dealing with people as they come: everything is the Way. “All dharmas are mind dharmas; all names are mind names. The myriad dharmas are all born from the mind; the mind is the root of the myriad dharmas. The sutra says, ‘It is because of knowing the mind and penetrating the original source that one is called a sramana. The names are equal, the meanings are equal: all dharmas are equal. They are all pure without mixing. If one attains to this teaching, then one is always free. If suchness is established, then everything is suchness. If the principle is established, then all dharmas are principle. If phenomena are established, then all dharmas are phenomena. When one is raised, thousands follow. The principle and phenomena are not different; everything is wonderful function, and there is no other principle. They all come from the mind.

“For instance, though the reflections of the moon are many, the real moon is only one. Though there are many springs of water, water has only one nature. There are myriad phenomena in the universe, but empty space is only one. There are many principles that are spoken of, but ‘unobstructed wisdom is only one.’ Whatever is established, it all comes from One Mind. Whether constructing or sweeping away, all is sublime function; all is oneself. There is no place to stand where ones leaves the Truth. The very place one stands on is the Truth; it is all one’s being. “All dharmas are Buddhadharmas, and all dharmas are liberation. Liberation is identical with suchness; all dharmas never leave suchness. Whether walking, standing, sitting, or reclining, everything is always inconceivable function. The sutras say that the Buddha is everywhere.“The Buddha is merciful and has wisdom. Knowing well the nature and character of all beings, he is able to break through the net of beings’ doubts. He has left the bondage of existence and nothingness; with all feelings of worldliness and holiness extinguished, he perceives that both self and dharmas are empty. He turns the incomparable Dharma wheel. Going beyond numbers and measures, his activity is unobstructed and he penetrates both principle and phenomena.“Like a cloud in the sky that suddenly appears and then is gone without leaving any traces; also like writing on water, neither born nor perishable: this is the Great Nirvana. In bondage it is called tathagatagarbha; when liberated it is called the pure dharmakaya. Dharmakaya is boundless, its essence neither increasing or decreasing. In order to respond to beings, it can manifest as big or small, square or round. It is like a reflection of the moon in water. It functions smoothly without establishing roots.“Not obliterating the conditioned; not dwelling in the unconditioned. The conditioned is the function of the unconditioned.; the unconditioned is the essence of the conditioned. Because of not dwelling on support, it has been said, ‘Like space which rest on nothing.’“The mind can be spoken of in terms of its two aspects: birth and death, and suchness. The mind as suchness is like a clear mirror which can reflect images. The mirror symbolizes the mind; the images symbolize the dharmas. If the mind grasps at dharmas, then it gets involved in external causes and conditions, which is the meaning of birth and death. If the mind does not grasp at dharmas, that is suchness.“The Sravakas hear about the Buddha-nature, while the Bodhisattva’s eye perceives the Buddha-nature. The realization of non-duality is called equal nature. Although the nature is free from differentiation, its function is not the same: when ignorant it is called consciousness; when awakened it is called wisdom. Following the principle is awakening, and following phenomena is ignorance. Ignorance is to be ignorant of one’s original mind. Awakening is to awake to one’s original nature. “Once awakened, one is awakened forever, there being no more ignorance. Like, when the sun comes, then all darkness disappears. When the sun of prajna emerges, it does not coexist with the darkness of defilements. If one comprehends the mind and the objects, then false thinking is not created again. When there is no more false thinking, that is acceptance of the non-arising of all dharmas. Originally it exists and it is present now, irrespective of cultivation of the Way and sitting in meditation.“Not cultivating and not sitting is the Tathagata’s pure meditation. If you now truly understand the real meaning of this, then do not create any karma. Content with your lot, pass your life. One bowl, one robe; whether sitting or standing, it is always with you. Keeping sila, you accumulate pure karma. If you can be like this, how can there be any worry that you will not realize? You have been standing long enough. Take care!”

Contested Identities in Chan/Zen Buddhism:

The “Lost” Fragments of Mazu Daoyi in the Zongjing lu

by Albert Welter

In: Buddhism Without Borders

Proceedings of the International Conference on Globalized Buddhism

Bumthang, Bhutan, May 21-23, 2012

http://archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/savifadok/2759/1/BuddhismConference1.pdf pp. 268-283.

Introduction: Mazu Daoyi and the Hongzhou Faction

Mazu Daoyi 馬祖道一, the founder of the Hongzhou faction is a major figure in

the Chinese Chan, Korean Seon and Japanese Zen traditions.i He is especially

credited with the unique Chan innovation known as “encounter dialogue.”

Encounter dialogues (jiyuan wenda 機緣問答) constitute one of the unique

features of Chan yulu 語緣, and served as a defining feature of the Chan

movement.ii Until recently, it was commonly assumed that yulu and encounter

dialogue were the products of a unique Tang Chan culture, initiated by masters

hailing form Chan’s so-called golden age.iii Recent work on the Linji lu 臨濟緣

exposed how dialogue records attributed to Linji were shaped over time into

typical encounter dialogue events that did not reach mature form until the early

Song.iv Regarding Mazu, Mario Poceski has shown how his reputation as an

i Many of the prevailing assumptions regarding Mazu and the Hongzhou school have been

challenged by the work of Mario Poceski, Everyday Mind as the Way: The Hongzhou School and the

Growth of Chan Buddhism (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), and Jia Jinhua. The

Hongzhou School of Chan Buddhism in Eighth- through Tenth-Century China (Albany, New York: State

University of New York Press, 2006).ii It is important to note that the term jiyuan wenda to describe the phenomena known in English as

“encounter dialogue” is a modern expedient devised by Yanagida Seizan 柳田聖山, without

precedent in original Chan sources. The significance of Hongzhou and Linji faction Chan to the

development of yulu and encounter dialogue is one of the presuppositions animating Yanagida

Seizan’s work on the development of Chan yulu, “Goroku no rekishi––zenbunken no seiritsu shiteki

kenkyû” 語録の歴史: 禅文献の成立史的研究 (Tōhō gakuhō 東方学報 57 [1985: 211-663]).iii Works discussing the development of yulu that challenges this view include Jinhua Jia, The

Hongzhou School of Buddhism; my own work, The Linji lu and the Creation of Chan Orthodoxy (New York

and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008); Urs App, “The Making of a Chan Record: Reflections on

the History of the Records of Yunmen” (Zen bunka kenkyūjo kiyō 禅文化研究所紀要 17 [1991: 1-90].); and

Mario Poceski, “Mazu yulu and the Creation of the Chan Records of Sayings,” in The Zen Canon. Ed.

Steven Heine and Dale Wright, pp. 53-81 (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004).

iv The Linji lu and the Creation of Chan Orthodoxy, especially pp. 81-108.

iconoclast derives from later sources.1 Morten Schlutter points out that in earlier

sources, Mazu “appears as a rather sedate and deliberate champion of the

doctrine of innate Buddha-nature,” and his record in the Zutang ji 祖堂集 gives a

decidedly less iconoclastic picture than in later sources.2 The view of Mazu as a

conventional sermonizer is borne out in the depiction of him in the Zongjing lu

宗鏡緣, in fragments that have been virtually ignored, especially in terms of their

significance, where Mazu appears as a scripture friendly exegete, citing canonical

at every turn and spinning at times elaborate commentaries around them. In the

current paper, I examine these “lost” (i.e., ignored) fragments in the Zongjing lu

that shed light on Mazu’s contested identity as a scriptural exegete.3

The Classic Image of Mazu and the Hongzhou Faction: Encounter Dialogue in

the Jingde Chuandeng lu

The classic image of Chan is determined by what may be referred to as the

“Mazu (and Hongzhou faction) perspective,” which I have described elsewhere

as follows:By the “Mazu perspective,” I am referring to a style and

interpretation of Chan attributed to the Mazu lineage, including

1 Poceski, “Mazu yulu and the Creation of the Chan Records of Sayings,” and Ordinary Mind as the

Way. Recently, Poceski has outlined a similar process in the case of records of Baizhang Huaihai’s

teachings, “Monastic Innovator, Iconoclast, and Teacher of Doctrine: The Varied Images of Chan

Master Baizhang,” Steven Heine and Dale Wright, eds. Zen Masters (New York and Oxford: Oxford

University Press, 2012).2 Schlütter, How Zen Became Zen (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2008), p. 16. Schlütter also

notes how this process also related to the development of the Platform sūtra, the early eighth century

version of which contains no encounter dialogues or antinomian behavior. On this, see Schlütter, “A

Study in the Genealogy of the Platform Sūtra,” Studies in Central and East Asian Religions 2. (1989: 53-

114). Schlütter credits David Chappell (p. 186, n. 19) as the first to note the discrepancy between the

earlier and later depictions of Mazu.3 The Zongjing lu is a work by the scholastic Chan master Yongming Yanshou who has been

uniformly marginalized in modern Chan and Zen interpretation as a “syncretist,” who represents a

decline in the fortunes of “pure” Zen. With the undermining of the supposition that Chan

transmission records (denglu or tôroku 燈錄) preserve faithful renderings of Tang Chan teachings, it is

no longer tenable to treat Yanshou’s record as anachronistic nostalgia for a bygone age, but to restore

his place as a participant in an ongoing debate about the nature of Chan that was a germane issue of

his age. The Chan fragments found in his works, virtually ignored for many years, also need to be

considered as viable alternatives to the way Chan masters are depicted in transmission records. For a

full treatment, see Welter, Scholastic as Chan Master: Yongming Yanshou’s Conception of Chan in the

Zongjing lu (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011). Much of the discussion that follows is taken

from my work there.

Mazu and his more immediate descendants. More than any

other Chan group, this contingent of masters is regarded in Chan

lore as the instigators of the “classic” Chan style and perspective,

memorialized in terms of a reputed Chan “golden age.” It is this

style and perspective that became the common property of Chan

masters in denglu texts, beginning with the Zutang ji and

Chuandeng lu. This common style and perspective represents the

standardization of Chan as a uniform tradition dedicated to

common goals and principles. While factional differences may

still have the potential to erupt into controversy, the

standardization of the Chan message and persona tended to

mask ideological disagreements. The standardization of Chan

also provided the pretext for a Chan orthodoxy that was no

longer the sole property of a distinct lineage.4

The “Mazu perspective” is typified by the development of encounter dialogues,

the witty, often physical and iconoclastic repartee between Chan protagonists

that characterizes their enlightened behaviour. While the encounter dialogue

genre became fully developed among Mazu’s descendents, it is also, by necessity,

projected on to the behaviour of Mazu himself as founder and hypothetical

progenitor of the style that his faction came to typify. Two examples from Mazu’s

record in the Jingde Chuandeng lu bear this out.

In the first example, an unidentified monk famed for his lectures on Buddhism

visits Mazu and asks him, “What is the teaching advocated by Chan masters?”, to

which Mazu posed a question in return: “What teaching do you uphold?” When

the learned monk replied that he had lectured on more that twenty scriptures

and treatises, Mazu exclaimed: “Are you not a lion (i.e., a Buddha)?” When the

monk declined the suggestion, Mazu huffed twice, prompting the monk to

comment: “This is the way to teach Chan.” When Mazu asked what he meant,

the monk replied: “It is the way the lion leaves the den.” When Mazu remained

silent, the monk interpreted it also as the way to teach Chan, commenting: “The

lion remains in the den.” When Mazu asked: “When there is neither leaving nor

remaining, what way would you say this was?”, the monk had no reply but bid

Mazu farewell. When the monk reached the door, Mazu called to him and he

4 Monks, Rulers, and Literati: the Political Ascendancy of Chan Buddhism (New York: Oxford Univeristy

Press, [2006: 69]).

immediately turned toward Mazu. Mazu again pressed him for a response, but

the monk still made no reply. Mazu yelled out: “What a stupid teacher!”5

The encounter dialogue here draws on a common trope of the Mazu faction

perspective, contrasting the Buddhist understanding of the learned exegete

against the penetrating insight of the Chan master. The example draws attention

to the typical way in which the Buddhist understanding of allegedly renowned

Buddhist exegetes is undermined, and revealed to be lacking the penetrating

insight of true awakening that Chan engenders. In a manner not uncommon in

encounter dialogues, the episode ends with the Chan master (Mazu) yelling out

his denunciation, “What a stupid teacher!” (which may be more colloquially

rendered: “You’re an idiot!”). Yelling and shouting in Chan––expressions of

spontaneous enlightened insight––displace the reasoned disputations of

exegetical discourse. Recourse to the trope of the renunciation of the learned

Buddhist exegete in Mazu’s discourses proves ironic in light of Yanshou’s

suggestion, considered in detail below, that Mazu himself epitomized in his

sermons the learned Buddhist exegesis that he is here criticizing.

A second example demonstrates that Mazu not only participated in shouting and

belittling techniques, but also fostered the physical denunciation practices that

Chan is renowned for. When a monk asked Mazu the common question intended

to test one’s Chan mettle: “What is the meaning of Bodhidharma coming from

the West?”, Mazu struck him, explaining, “If I do not strike you, people

throughout the country will laugh at me.”6

The above examples typify the way in which Mazu’s image as an iconoclast has

been received in the Chan and Zen traditions. This image is ubiquitous to the

point of being unchallengeable. It solidifies Mazu’s image as the progenitor of a

movement that came to represent an orthodox interpretation of Chan and Zen

enshrined in classic sources like the Jingde Chuandeng lu.

The “Lost” Fragments: Mazu as Sermonizing Exegete in the Zongjing lu

In spite of the rather tame, prosaic character of the teachings attributed to

Hongzhou 洪州 masters like Mazu in early sources, his reputation in the Chan

5 CDL 6 (T 51.246b). Following Chang Chung-yuan, trans. Original Teachings of Ch’an Buddhism (New

York: Vintage Books, [1971: 151-152]).6 CDL 6 (T 51.246b). Following Chang Chung-yuan, trans. Original Teachings of Ch’an Buddhism, p. 150.

and Zen traditions affirms his central role as the progenitor of the iconoclastic

movement Chan and Zen are most noted for. Yongming Yanshou 永明延壽,

compiler of the Zongjing lu, acknowledged what must have been a growing trend

to interpret Mazu as an iconoclast, a trend that was already evident in the late

Tang critiques by the scholastic Chan protagonist, Zongmi 宗密.7 Yanshou

inherited Zongmi’s concerns, and the Zongjing lu was written, in part, to counter

this trend by proposing that Mazu’s teaching was not iconoclastic, but fully

compatible with doctrinal teachings.

This line of argument represents a significant change in our understanding of

Yanshou and his position in the development of Chan. Previously, when Mazu

was assumed to be the champion of radical, iconoclastic Chan, characterized by

an aggressive antinomian posturing, Yanshou’s characterization of Mazu was

deemed an anachronistic fancy, a wishful fantasy of who Yanshu would like

Mazu to be, but a far cry from who Mazu actually was. The discovery of the

Zutang ji in the twentieth century, coupled with a more nuanced text-critical

approach to the sources of Mazu’s teachings, have reshaped our understanding

of Mazu along the lines described above, and made us more aware of the forces

in the later Chan tradition that animated Mazu as champion of Chan iconoclasm.

This makes a reevaluation of Yanshou’s characterization of Mazu both timely

and significant. This is not to suggest that Yanshou’s depiction of Mazu is

unbiased, or lacking in motivations close to Yanshou’s own heart. It does suggest

that Yanshou’s characterization not be casually discarded as irrelevant, but be

entertained as a further piece in our understanding of Mazu and the pressures

influencing how he came to interpreted within the Chan community.

In the eyes of Yanshou, Mazu Daoyi and other Hongzhou faction masters were

like any other Chan master worthy of the name, relying on scripturally based

doctrinal teachings to promote Chan principles. On the basis of this, the

suggestion that the Mazu inspired Hongzhou faction stood for an interpretation

of Chan independent of the scriptures and doctrinally based Buddhist practices

was untenable. In order to demonstrate the effect of Yanshou’s portrayal, I

contrast fragments of Mazu’s teaching in the Zongjing lu against those recorded

in Chan transmission records that came to inform his image as an iconoclast.

7 See Jeffrey Broughton, Zongmi on Chan (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009); Peter N.

Gregory, Tsung-mi and the Sinification of Buddhism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991); and

Jan Yün-hua 冉雲華. “Tsung-mi, His Analysis of Chan Buddhism,” T’oung Pao 58 (1972: 1-54).

Perhaps the most telling fragment is the fragment of Mazu’s teaching in the

Zongjing lu that contains a commentary on the meaning of the key Lankavatāra

sūtra passage: “Buddha taught that mind is the implicit truth (zong), and

‘gatelessness’ (wumen) is the dharma-gate.” Because of its length and for the sake

of comparison with other sources, I have broken the commentary into four

sections. The first three sections have no counterpart in either the Zutang ji or

Chuandeng lu 傳燈緣; they appear solely in the Zongjing lu.8

Section 1

何故佛語心為宗。佛語心者。即心即佛。今語即是心語。故云。

佛語心為宗。無門為法門者。達本性空。更無一法。性自是門。

性無有相。亦無有門。故云。無門為法門。亦名空門。亦名色門

。何以故。空是法性空。色是法性色。無形相故。謂之空。知見

無盡故。謂之色。

Why does [the Lankavatāra sūtra say] “Buddha taught that mind

is the implicit truth?” As for “Buddha taught that mind is the

implicit truth,” mind is Buddha. Because the words currently

[attributed to the Buddha] are mind-words (i.e., designations for

mind; xinyu), when it says, “Buddha taught that mind is the

implicit truth, and ‘gatelessness’ is the dharma-gate,” [it means

that] they understood the emptiness of the inherent nature [of

things] (benxing), on top of which there is not a single dharma.

Nature itself is the gateway. But because nature has no form and

also lacks a gateway to access it, [the sūtra] says “‘gatelessness’ is

the dharma-gate.” Why is it also known as the “gate of

emptiness (kongmen),” and as the “gate of physical forms”

(semen)? Emptiness refers to the emptiness of the dharma-nature;

physical forms refer to the physical forms of the dharma-nature.

Because the dharma-nature has no shape or form, it is referred to

as “empty.” Because the dharma-nature is known and seen in

everything without limit, it is referred to as “physical forms.”

8 The commentary is found in Zongjing lu 1 (T 49.418b16-c5).

Section 2

故云。如來色無盡。智慧亦復然。隨生諸法處。復有無量三昧門

。遠離內外知見情執。亦名總持門。亦名施門。謂不念內外善惡

諸法。乃至皆是諸波羅蜜門。色身佛。是實相佛家用。經云。三

十二相。八十種好。皆從心想生。亦名法性家焰。亦法性功勳。

菩薩行般若時。火燒三界內外諸物盡。於中不損一草葉。為諸法

如相故。故經云。不壞於身而隨一相。今知自性是佛。於一切時

中行住坐臥。更無一法可得。乃至真如不屬一切名。亦無無名。

故經云。智不得有無。

Therefore, the scriptures say:9 “The physical forms of the

tathāgata are unlimited, and wisdom is also like this as well (i.e.,

unlimited).” Since the various dharmas occupy their respective

positions in accordance with the process of arising, they also

serve as inestimable gateways to samādhi. Distancing oneself far

from emotional attachments to what is known internally and

seen externally is referred to as the gateway to esoteric

techniques, on the one hand, and as the gateway to practices that

bestow blessings, on the other.10 It means that when one does not

think of the various dharmas as subjective or objective, as good

or evil, the various dharmas all become gateways to the

pāramitās. The Buddha comprised of a physical body (sesheng fo)

9 This line appears in both a gatha in the Da baoji jing 大寶積經 (Scriptures of the Great Treasure

Storehouse; T 11-310.673a7), and in Fazang’s 法藏 commentary to the Awakening of Faith, the Dacheng

qixinlun lunyi ji 大乘起信論義記 (T 44-1846.247a27-28), where it is attributed to the Shengman jing

勝鬘經.10 The reference to “the gateway to esoteric techniques” (zongchi men 總持門) corresponds to “what is

known internally.” “Practices which bestow blessings” (shimen 施門) refer especially to the practice of

almsgiving, corresponding here to “what is seen externally.”

is the true form [of the Buddha] (shixiang) used by members of

the Buddhist faith.11The scriptures say:12

“The thirty-two distinctive marks and the

eighty distinctive bodily characteristics [of a Buddha] are all

products of imagination.”13

They (i.e., the scriptures) also refer to it (i.e., the Buddha’s

physical body) as the blazing house of the dharma-nature, or as

the meritorious deeds of the dharma-nature.14 When

bodhisattvas practice prajñā, the fire [of wisdom] incinerates

everything in the three realms [of desire, form and formlessness],

whether subjective or objective, but does not harm a single blade

of grass or leaf in the process. The reason is that the various

dharmas are forms existing in the state of suchness (ruxiang).15

That is why a scripture [Vimālakīrti sūtra] says: 16 “Do no harm to

11 Pan Guiming, the translator of selected sections of the Zongjing lu into modern Chinese (Zongjing lu,

Foguangshan, [1996: 36 & 39]), punctuates the text so as to make the last two characters of this

sentence, jiayong (literally, “house use,” or “used ‘in-house’”) the title of the scripture that follows, the

Jiayong jing 家用經. As there is no scripture bearing such a title, I have refrained from following this

suggestion, and have taken the cited scripture as an abbreviated reference to the Guan wuliangshou

jing 觀無量壽經 (see below).12 An abbreviated citation from the Guan wuliangshou jing 觀無量壽經 (T 12.343a21-22).

13 The thirty-two distinctive marks and eighty distinctive bodily traits are auspicious signs

accompanying the physical attributes of a Buddha, distinguishing him from ordinary human beings.

A common list of the thirty-two distinctive marks are: flat soles; dharma-wheel insignia on the soles

of the feet; slender fingers; tender limbs; webbed fingers and toes; round heels; long legs; slender legs

like those of a deer; arms extending past the knees; a concealed penis; arm-span equal to the height of

the body; light radiating from the pores; curly body hair; golden body; light radiating from the body

ten feet in each direction; tender shins; legs; palms; shoulders; and neck of the same proportion;

swollen armpits; a dignified body like a lion; an erect body; full shoulders; forty teeth; firm, white

teeth; four white canine teeth; full cheeks like those of a lion; flavoured saliva; a long, slender tongue;

a beautiful voice; blue eyes; eyes resembling those of a bull; a bump between the eyes; and a bump on

top of the head. These are listed in Guan wuliangshou jing (T 12.343a); the list here is drawn from

Japanese-English Buddhist Dictionary: 255a (see also Nakamura: 472d-473d).

The eighty distinctive bodily traits represent similarly construed, finer details of a Buddha’s physical

appearance. They are discussed in fascicle 2 of the Dîrghâgama sûtra (Pali: Dîgha nikâya; C. Zhang ahan

jing 長阿含經 [T1.12b]; see Nakamura: 1103c-d, Japanese-English Buddhist Dictionary: 95b-96a).14 The reference to the burning house is undoubtedly to the parable contained in the Lotus sūtra; given

the context, the reference to meritorious deeds is likely to the Lotus as well.15 The term ruxiang 如相 (suchness) is common in Chinese Buddhism. It appears, for instance, in the

Weimo jing 維摩經 (Vimâlakîrti sûtra); T 14.547b22).16 This phrase is found in Kumarajiva’s translation of the Vimâlakîrti sûtra (Weimo jing; T 14.540b24),

and appears in various Chinese Buddhist commentaries: Sengzhao’s 僧肇 Zhu Weimojie jing

注維摩詰經 (T 38.350a25); Zhiyi's 智顗 Weimo jing lueshu 維摩經略述, summarized by Zhanran 湛然 (T

38.619c17 & 668c15); Zhiyi's Jinguangming jing wenju 金光明經文句, recorded by Guanding 灌頂 (T

39.51a6); Guanding's Guanxin lun 觀心論 (T 46.588b27 & 599b18); and Jizang's Jingming xuanlun

淨名玄論 (T 38.847a22) and Weimo jing yishu 維摩經義疏 (T 38.940c1).

the physical body, and be in accord with the universal form

[underlying all phenomena] (yixiang).

”Since we now know that [our own] self-nature is Buddha, no

matter what the situation, whether walking, standing, sitting, or

lying down, there is not a single dharma that can be obtained.

And even though true suchness (zhenru) is not limited by any

name, there are no names that do not refer to it. This is why a

scripture [Lankavatāra sūtra] says: 17 “Wisdom is not obtained in

existence or non-existence.”18

Section 3

內外無求。任其本性。亦無任性之心。經云。種種意生身。我說

為心量。即無心之心。無量之量。無名為真名。無求是真求。

Internally or externally, there is nothing to seek. Let your original

nature (benxing) reign free, but do not give reign to a “mind”

(xin) [that exists over and above] nature (xing). When a scripture

(the Lankavatāra sūtra) says: 19 “All the various deliberations give

17 A line from a verse in the Lengqie jing 楞伽經 (Lankavatāra sūtra; T 16.480a28, 480b1 & b3). What

follows in the sûtra is, in each case, the verse: “... and yet one gives rise to a mind of great

compassion.” The line also appears in Jizang’s (T 35.386b22) and Chengguan’s (eg., T 35.855a19)

commentaries on the Huayan jing 華嚴經; and Zongmi’s Da fangguang yuanjue xiuduoluo liaoyi jing

lueshu zhu 大方廣圓覺修多羅了義經略述註 (T 39.541b4).18 The first thing to note here is that some lines from this section are also attributed to Qingyuan

Xingsi 青原行思. Zongjing lu 97: T 48.940b24-26 & 28. The teaching attributed to Qingyuan Xingsi

there reads:

…is the true form [of the Buddha] (shixiang 實相) used by members of the Buddhist faith.

The scriptures say: “The thirty-two distinctive marks and the eighty distinctive bodily

characteristics [of a Buddha] are all products of imagination.” They (i.e., the scriptures) also

say (i.e., the Buddha’s physical body) is the blazing house of the dharma-nature, and also

the meritorious deeds of the dharma-nature….no matter what the situation, there is not a

single dharma that can be obtained.”19 Lines from a verse in the Lengqie ching 楞伽經 (T 16.500b17). “Contents of the mind” (xinliang 心量)

is another name for “mind-only” (weixin 唯心) (Nakamura, Bukkyôgo daijiten 770a).

rise to [notions of] physical bodies; I say they are accumulations

of the mind (i.e., mind-only),” it refers to ‘mindless mind’ (wuxin

zhi xin, i.e., the mind of ‘no-mind’, or a mind of spontaneous

freedom) and ‘contentless contents’ (i.e., the contents of ‘nocontents’).

The ‘nameless’ is the true name.20 ‘Non-seeking’ is

true seeking.

______________________________________________________________

The long commentary from Mazu, cited in sections 1 through 3 above, has no

counterpart in the Zutang ji or Chuandeng lu 傳燈緣. The only portion of the

commentary from the Zongjing lu recorded in the Zutang ji and Chuandeng lu is

the fragment cited below (section 4). The fragment is recorded in the Zongjing lu,

as follows:21

Section 4

經云。夫求法者。應無所求。心外無別佛。佛外無別心。不取善

不作惡。淨穢兩邊俱不依。法無自性。三界唯心。經云。森羅及

萬像。一法之所印。凡所見色。皆是見心。心不自心。因色故心

。色不自色。因心故色。故經云。見色即是見心。

[According to Mazu Daoyi]:22

The scriptures say: “Those who seek the Dharma (fa) should not

seek anything.”23 There is no Buddha separate from mind; there

20 An allusion to passages regarding the nameless (wuming 無名) in the Daode jing

道德經.21 Zongjing lu 1; 418c5-10.

22 Although there is no attribution to Mazu by Yanshou in the Zongjing lu text, these lines clearly

correspond to the Mazu yulu 馬祖語緣 (X 69 2b22ff.; Iriya Yoshitaka 入矢義高, trans., Baso no goroku

馬祖の語録 (Kyoto: Zenbunka kenkyūjo, [1984: 19-21]), and other sources that record Mazu’s

teachings, the Jingde Chuandeng lu 景德傳燈緣 (T 51.246a9ff.), and the Tiansheng Guangdeng lu

天聖廣燈緣 (X 78.448c11ff.).23 This is a common assertion found in Buddhist scriptures; see for example, the Weimo jing

(Vimālakīrti sūtra; T 14.546a25-26). “There is nothing to seek” is one of the four practices attributed to

Bodhidharma in the “Treatise on the Two Entrances and Four Practice” (Erru sixing lun 二入四行論).

In the Mazu yulu and Tiansheng Guangdeng lu this passage is not attributed to a scripture but to Mazu

himself. The Jingde Chuandeng lu concurs with the Zongjing lu in attributing the statement to a

scriptural source.

is no mind separate from Buddha. Do not grasp good; do not

create evil.24 In both realms, the pure and the defiled, there is

nothing to depend on. Phenomena (fa) have no intrinsic nature.

The triple realm is simply [the manifestation of] mind (weixin).

The scriptures say: “Infinite existence and its myriad images bear

the seal of a single truth.”25 Whenever we see physical forms, we

are seeing mind. Mind is not mind of itself. Mind is mind

because of physical forms.26 Physical forms are not physical

forms of themselves. Physical forms are physical forms because

of mind. That is why the scriptures say: “To see physical forms is

to see mind.”27

The Zutang ji and Chuandeng lu versions are virtually identical, and read as

follows.28

______________________________________________________________

又云。夫求法者。應無所求。心外無別佛。佛外無別心。不取善

不捨惡。淨穢兩邊俱不依怙。。念念不可得。無自性故。

三界唯心。森羅萬象。一法之所印。凡所見色皆是見心。心不自

心。因色故有心。

It [the Lankavatāra sūtra] also says: “Those who seek the Dharma

should not seek anything.”29 There is no Buddha separate from

24 The Mazu yulu and other sources have shewu 攝惡 (“reject evil”) for zuowu 作惡 (“create evil”).

25 This phrase, “Infinite existence and its myriad images bear the seal of a single truth,” is found in the

Chan apocryphal text, the Faju jing 法句經 (T 85.1435a23), cited by Chengguan 澄觀 in his

commentary on the Huayan jing (T 36.60c28-29 & 586b6-7). Elsewhere in the commentary (T

36.301b16-17), Chengguan attributes the phrase to a Prajňāparāmita source.26 This is where the Mazu yulu and other sources end. I have attributed the following lines to Mazu,

however, as best fitting the context of the Zongjing lu.27 The phrase is reminiscent of general Māhayāna teaching. With slight variation, it appears in the

Panro xinjing zhujie 般若心經註解 (Commentary on the Heart Sūtra) by Patriarch Dadian 大顛祖師 (X

26-573.949a1), suggesting that the phrase is an extrapolation of Heart Sūtra teaching (see T 8-

251.848c4-23).28 Save for the character xin 心 at the end of the Zutang ji passage, which the Chuandeng lu lacks, the

two versions are identical.29 As noted above, this is a common assertion found in Buddhist scriptures; see for example, the

Weimo jing (Vimālakīrti sūtra; T 14.546a25-26). “There is nothing to seek” is one of the four practices

attributed to Bodhidharma in the “Treatise on the Two Entrances and Four Practice” (Erru sixing lun).

Here it appears to be attributed to the Lankavatāra sūtra.

mind; there is no mind separate from Buddha. Do not grasp

good; do not reject evil.30 In both realms, the pure and the

defiled, there is nothing to depend on. Sinfulness, by nature, is

empty; passing thoughts are incapable of [committing sins]

because they have no intrinsic nature of their own. Therefore, the

triple realm is simply [the manifestation of] mind (weixin).

Infinite existence and its myriad images bear the seal of a single

truth.31 Whenever we see physical forms, we are seeing mind.

Mind is not mind of itself; the existence of mind depends on

physical forms.32(Zutang ji 14; ZBK ed. 514.8-13 & Chuandeng lu 6; T 51.246a9-14)

______________________________________________________________

The Zutang ji and Chuandeng lu, in effect, skip the long exegetical commentary

attributed to Mazu in the Zongjing lu, cited in sections 1 through 3 above, and go

directly to a second scripture quotation, which they attribute, by inference, to the

Lankavatāra sūtra. Even here, where the Zongjing lu punctuates Mazu’s comments

with citations from scriptures to verify the accuracy of his interpretation

(concurring with Yanshou’s own stipulated methodology for revealing zong, the

implicit truth), the Zutang ji and Chuandeng lu simply cite the Lankavatāra briefly

and attribute the rest of the passage to Mazu himself. This effectively makes

Mazu the authority, not the scriptures. Ishii Kôsei has suggested that the role of

the Lankavâtara sūtra in Mazu’s teachings lessens from the Zongjing lu to the

Zutang ji to the Chuandeng lu.33 The omission of the long commentary attributed

to Mazu in the Zongjing lu only reinforces this point. In the Zongjing lu, Mazu is

depicted as a traditional Buddhist master, whose intimate knowledge of the

scriptures and interpretive acumen are readily apparent. The presentation of

30 See n. 28 above.31 As noted above, this phrase, “Infinite existence and its myriad images bear the seal of a single

truth,” is found in the Chan apocryphal text, the Faju jing (T 85.1435a23), cited by Chengguan in his

commentary on the Huayan jing (T 36.60c28-29 & 586b6-7). While Yanshou acknowledges its

scriptural origin, the Chuandeng lu and other sources portray it as Mazu’s own declaration.32 This is where the Mazu yulu ends. I have attributed the following lines to Mazu, however, as best

fitting the context of the Zongjing lu.33 Ishii Kôsei 石井公成, “Baso ni okeru Ranka kyō, Ninyū sigyō ron no iyō”

馬祖における『楞伽経』『二入四行論』の依用, Komazawa tanki daigaku ronshū 11 (2005: 112-114).

Mazu as a Buddhist exegete conflicted strongly with the aims of later Chan

lineage advocates. The latter shaped Mazu’s image so as to minimize Mazu’s

scripture-friendly persona and exegetical tendencies.

In addition, one other item of note is the substitution of the character she 捨 (to

reject) in the Zutang ji and Chuandeng lu in place of the character zuo 作 (to create)

in the Zongjng lu version. This changes the Zongjing lu line: “Do not grasp good;

do not create evil” (不取善不作惡) to read “Do not grasp good; do not reject evil

(不取善不捨惡)” in the Zutang ji and Chuandeng lu versions. The Zutang ji and

Chuandeng lu versions were eventually standardized in the Mazu yulu 馬祖語緣.

This small alteration effectively changes Mazu from advocating a conventional

Buddhist morality, “do not create evil” into an advocate of an antinomian Chan,

“do not reject evil,” that has transcended the limitations of a moral dualism

(good versus evil).

The Mazu yulu also incorporates the passages cited above from the Zutang ji and