ZEN IRODALOM ZEN LITERATURE

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

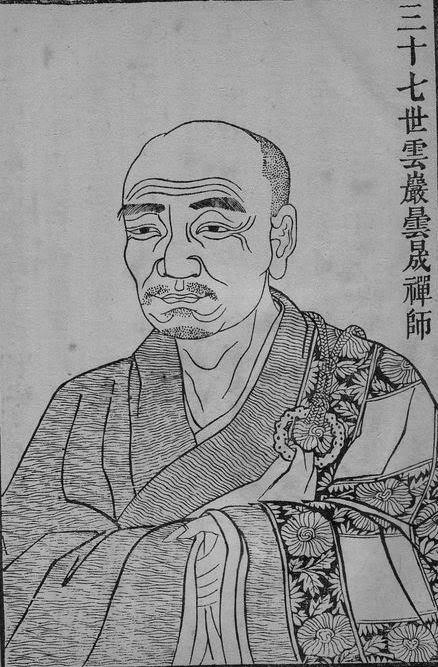

雲巖曇晟 Yunyan Tansheng (780-841)

(Rōmaji:) Ungan Donjō

(Magyar:) Jün-jen Tan-seng

Tartalom |

Contents |

| Jün-jen Tan-seng összegyűjtött mondásaiból Fordította: Terebess Gábor |

The Record of Yunyan Tansheng YUNYAN TANSHENG YUN-YEN |

![]()

The Record of Yunyan Tansheng

Mitchell, James. Soto Zen Ancestors in China: The Recorded Teachings of Shitou

Xiqian, Yaoshan Weiyan And Yunyan Tansheng. San Francisco: Ithuriel's Spear, 2005.

PDF > Excerpts in PDF-OCR

Text used for the translation:

Wu deng hui yuan. [Wu-teng hui-yuan. Five Lamps Merged in the Source.

Compiled by Monk Pu Ji and Monk Hui Ming.] This edition edited by Yuanlei Su,

China Publishing House (Zhonghua Shu Ju), Beijing: 1984.

Chan Master Yunyan Tansheng of Tanzhou was born to a family named Wang at Zhongling.

He became a monk at Shimen Temple when he was quite young and practiced chan with

Master Baizhang Huaihai. Twenty years afterwards, since he had no affinity with Baizhang,

he left for Yaoshan's temple.

Tanzhou is an older name for Changsha, the present capital of Hunan Province. Zhongling is

located in modern Jiangxi Province. Baizhang Huaihai (749-814) is one of the most famous of

all Tang-period chan masters and is remembered mainly for his work on monastic rules for

the chan school, which in later centuries became normative for Chinese Buddhism in

general. He was a disciple of Mazu and became the teacher of Huang Po. It is remarkable

to think that Dongshan Liangjie's teacher Yunyan studied with Baizhang for 20 years before

turning to Yaoshan for transmission.

Yaoshan asked Yunyan where he had come from. Yunyan answered from Baizhang. Yaoshan

asked what Baizhang usually said to his students. Yunyan answered, "He often said, 'I've got

a sentence which includes all tastes." [I can state a proposition which contains all

meanings.] Yaoshan said, "Salty is salty, plain is plain, neither salty nor plain is the way

things taste normally. How can there be a sentence which contains all tastes?" Yunyan

couldn't respond. Yaoshan said, "How can we deal with the problem of life and death?"

Yunyan said, "I haven't studied this yet." Yaoshan asked, "How long did you stay with

Baizhang?" Yunyan said 20 years, and Yaoshan said, "After 20 years with Baizhang you still

haven't given up your worldly views."

"The 'one taste' means there is no attachment, no contamination, no purity, no nihilism, no

eternalism, no arising, no cessation, no grasping, no abandoning, no self, and no sensation."

Garma Chang, A Treasury of Mahayana Sutras, Maharatnakuta Sutra, "Manjusri's Attainment of

Buddhahood," p. 172.

Sometime later, Yaoshan asked what else Baizhang had said. Yunyan answered, "Sometimes

he told me that I should think only about what is beyond the Three Propositions." Yaoshan

said, "It's a good thing I'm 3,000 li away from Baizhang and don't have to deal with him."

The Three Propositions are: to give up thinking about existence, to give up thinking about

non-existence, and to give up thinking about existence and non-existence.

Sometime later, Yaoshan asked Yunyan what else Baizhang said to him. Yunyan answered,

"Once in the lecture hall, when all the monks were standing there, the master drove us out

with his walking stick. Then he called us back and asked, "What is this?" Yaoshan said, "Why

didn’t you tell me this before? Now I'm really getting to understand Master Huaihai."

Hearing this, Yaoshan suddenly awakened and bowed down before Yaoshan.

On another day, Yaoshan asked, "Where else have you been besides with Baizhang?" Yunyan

said, "I've been to some places in Guangnan and Guangxi." Yaoshan said, "I heard once that

there was a big stone outside the east gate of Guangzhou city, which was eventually

removed by order of the mayor, is that true?" Yunyan answered, "It couldn't be removed by

all the efforts of all the people in all the country, let alone by the mayor."

Yaoshan again asked, "You know how to perform the lion's dance, don't you?" Yunyan said

yes. "How many different styles can you perform?" Yunyan answered six. Yaoshan said, "I can

do it too." Yunyan asked, "How many kinds can you do?" Yaoshan said, "Just one." Yunyan

said, "Six is one, and one is six."

The lion-dance is as popular today as it was in Yunyan's times; it is performed at Chinese

New Year's and other festivals. Two or three persons dressed in a lion's costume with an

oversized lion's head chase through the streets, pretending to bite the by-standers. Being

"bitten" by the lion brings good fortune. The idea of this dialogue is that since all things are

empty, and since emptiness is characterized by thusness, all numbers are therefore equal.

Later, Yunyan went to see Weishan. Weishan asked, "I heard you performed the lion's dance

at Yaoshan's place last night, is that true?" Yunyan said, "That's right." Weishan said, "Did

you perform it without stopping, or did you take a break sometimes?" Yunyan said, "When I

felt like dancing, I danced, and when I felt like stopping, I stopped." Weishan asked, "When

it was over, what happened to the lion?" Yunyan said, "Gone, gone."

A monk asked, "What ever became of the ancient sages?" Yunyan said after a long pause,

"What did you say?" The monk said, "What should we do with someone who is as oblivious

as a dead person?" Yunyan said, "Bury him." The monk asked again, "Is it like that with

highly realized persons?" Yunyan asked, "Is the silk woven from the same loom one piece or

two?"

Yunyan was boiling some tea. Daowu asked who he was making it for. Yunyan answered,

"Nobody special." Daowu said, "Why doesn't he go make it for himself?" Yunyan said, "It's a

good thing that I’m here."

Yunyan asked Shishuang, "Where have you come from?" "From Weishan." Yunyan asked,

"How long were you there?" Shishuang said one year. Yunyan said, "So you could have

become the head of the monastery." Shishuang said, "Although I was there, I didn't learn

anything." Yunyan said, "Weishan didn't learn anything either." Shishuang had nothing to

say.

Yunyan was speaking to everyone in the lecture hall. "Once there was a son in a family who

could answer any question that was put to him." Dongshan Liangjie stepped forward and

asked, "How many books of the Chinese classics did these people have in their house?"

Yunyan said, "Not a single word." Dongshan said, "Then how could the son become so

educated?" Yunyan said, "He didn't sleep nights." Dongshan asked, "Can you answer me if I

ask you a question?" Yunyan said, "I could, but I'm not going to."

Yunyan asked a monk, "Where have you been?" The monk replied, "I was just putting on

some more incense." Yunyan asked, "Did you see Buddha?" "Yes, I did." "Where did you see

him?" The monk said, "In the human world." Yunyan praised him: "You're just like the

ancient Budddhas."

Daowu asked, "The God of Compassion has thousands of eyes – which is the most important

one?" Yunyan said, "It's like when a person reaches out for his pillow in the middle of the

night." Daowu said, "I understand." Yunyan asked, "What do you understand?" Daowu said,

"There are eyes all over one's body." Yunyan replied, "You said that so directly that you are

only 80 correct." Daowu said, "So how do you understand this?" % Yunyan said, "Ther e are

eyes all over one's body."

Avalokitesvara, the bodhisattva of infinite compassion, has many arms to help people and

also many eyes to see their needs. He helps them instinctively and spontaneously, as a

person might adjust his pillow at night while remaining asleep.

Yunyan was sweeping the floor. Daowu said, "What you're doing is such a menial task."

Yunyan said, "One should see it as something very important." Daowu asked, "You might as

well suppose that there two moons." Yunyan held up his broom and said, "Which moon is

this?" Daowu walked off.

Yunyan asked a monk what he was doing. The monk replied, "I've been talking to a rock."

Yunyan said, "Did it nod to you [indicating that it understood you]? When the monk didn't

reply, Yunyan answered for him: "It nodded to you before you even said anything."

Yunyan was weaving a pair of straw shoes. Dongshan came up and said, "May I borrow your

eyes?" Yunyan said, "Who did you lend yours to?" Dongshan said, "I don't have any eyes."

Yunyan said, "Isn't it your eyes which are borrowing your eyes?" When Dongshan said no,

Yunyan told him to get out.

A monk asked, "What if I fell into an evil world because of desire?" Yunyan asked, "What

makes you think you're in the Buddhist world?" The monk didn't answer. Yunyan asked if he

had understood. The monk said he hadn't. Yunyan said, "Even if you had, you'd still be

wandering between the evil world and the Buddhist world." [You'd still be lost in duality.]

On the 26th day of the tenth month in the first year of the Hui Chang Emperor [= December,

841 CE], Yunyan fell ill. In the night of the next day, he passed away. There were over one

thousand relics after the cremation, which were then buried under a memorial stupa. He

was accorded the title Great Master Wu Zhu — "Continuing Forever."

YUN-YEN

Translated by Thomas Cleary

In: The five houses of Zen, 1997

Sayings

ONE DAY YUN-YEN said to a group, “There is an offspring of someone’s house who can answer any question.”

Tung-shan asked, “How many books does he have in his house?”

Yun-yen said, “There is not even a single letter.”

Tung-shan asked, “Then how did he get so much knowledge?”

Yun-yen said, “Never sleeping, day or night.”

As Yun-yen was sweeping the grounds, Kuei-shan said, “Too busy!”

Yun-yen said, “You should know there is one who is not busy.”

Kuei-shan said, “Then there is a second moon.”

Yun-yen stood the broom up and said, “Which moon is this?”

Kuei-shan lowered his head and left. Hsuan-sha heard about this and said, “Precisely the second moon!”

As Yun-yen was making straw sandals, Tung-shan said to him, “If I ask you for perception, can I get it?”

Yun-yen replied, “To whom did you give away yours?”

Tung-shan said, “I have none.”

Yun-yen said, “If you had, where would you put it?”

Tung-shan said nothing.

Yun-yen asked, “What about that which asks for perception; is that perception?”

Tung-shan said, “It is not perception.”

Yun-yen disapproved.

Yun-yen asked a nun, “Is your father still alive?”

She said, “Yes.”

Yun-yen asked, “How old is he?”

She said, “Eighty years old.”

Yun-yen said, “You have a father who is not eighty years old; do you know?”

She replied, “Is this not ‘the one who comes thus’?”

Yun-yen said, “That is just a descendant!”

A monk asked, “How is it when one falls into the realm of demons the moment a thought occurs?”

Yun-yen said, “Why did you come from the realm of buddhas?”

The monk had no reply.

Yun-yen said, “Understand?”

The monk said, “No.”

Yun-yen said, “Don’t say you don’t comprehend; even if you do comprehend, you’re just beating around the bush.”

YUNYAN TANSHENG

IN: Zen's Chinese heritage: the masters and their teachings

by Andy Ferguson

Boston: Wisdom Publications, 2000. pp. 160-163.

YUNYAN TANSHENG (780–841) was a disciple of Yaoshan Weiyan. Yunyan came from ancient Jianchang.96 Although he studied for about twenty years under Baizhang Huaihai he did not attain enlightenment. After Baizhang passed away, Yunyan traveled to many other teachers before completely ripening under Yaoshan. Yunyan was a close friend of his fellow student Daowu Yuanzhi. The recorded exchanges between these two monks were widely known and quoted by later generations of Zen students. Yunyan later lived on Yunyan Mountain in Tanzhou (near modern Changsha). Among his Dharma heirs was Dongshan Liangjie, the founder of the Caodong (in Japanese, Sōtō) Zen school.

Yunyan Tansheng of Tanzhou came from Jianchang in Zhongling. His lay name was Wang. He left home at a young age to live at Shimen Mountain.97 He studied under Baizhang Huaihai for twenty years but did not meet with the source. Later, he studied with Yaoshan.

Yaoshan asked him, “Where have you come from?”

Yunyan answered, “From Baizhang.”

Yaoshan asked, “What did Baizhang say to his disciples?”

Yunyan said, “He often said, ‘I have a saying which is, “The hundred tastes are complete.”’”

Yaoshan said, “Something salty tastes salty. Something bland tastes bland. What is neither salty nor bland is a normal taste. What is meant by the phrase, ‘One hundred tastes are complete’?”

Yunyan couldn’t answer.

Yaoshan said, “What did Baizhang say about the life and death before our eyes?”

Yunyan said, “He said that there is no life and death before our eyes.”

Yaoshan said, “How long were you at Baizhang’s place?”

Yunyan said, “Twenty years.”

Yaoshan said, “So you spent twenty years with Baizhang, but you still haven’t rid yourself of rustic ways.”

One day when Yunyan was serving as Yaoshan’s attendant, Yaoshan asked him, “What else did Baizhang have to say?”

Yunyan said, “Once he said, ‘Go beyond three phrases and enlightenment’s gone. But within six phrases there’s comprehension.’”

Yaoshan said, “Three thousand miles distant the joy can’t be felt.”

Then Yaoshan said, “What else did Baizhang say?”

Yunyan said, “Once Baizhang entered the hall to address the monks. Everyone stood. He then used his staff to drive everyone out. Then he yelled at the monks, and when they looked back at him he said, ‘What is it?’”

Yaoshan said, “Why didn’t you tell me this before. Thanks to you today I’ve finally seen elder brother Hai.”

Upon hearing these words Yunyan attained enlightenment.

One day Yaoshan asked, “Besides living at Mt. Baizhang, where else have you been?”

Yunyan answered, “I was in Guangnan [Southern China].”

Yaoshan said, “I’ve heard that east of the city gate of Guangzhou there is a great rock that the local governor can’t move, is that so?”

Yunyan said, “Not only the governor! Everyone in the country together can’t move it!”

One day Yaoshan said, “I’ve heard that you can tame lions. Is that so?”

Yunyan said, “Yes.”

Yaoshan said, “How many can you tame?”

Yunyan said, “Six.”

Yaoshan said, “I can tame them too.”

Yunyan asked, “How many does the master tame?”

Yaoshan said, “One.”

Yunyan said, “One is six. Six is one.”

Later, Yunyan was at Mt. Gui.

Guishan asked him, “I’ve often heard that when you were at Yaoshan you tamed lions. Is that so?”

Yunyan said, “Yes.”

Guishan asked, “Were they always under control, or just sometimes?”

Yunyan said, “When I wanted them under control they were under control. When I wanted to let them loose, they ran loose.”

Guishan said, “When they ran loose where were they?”

Yunyan said, “They’re loose! They’re loose!”

Yunyan was making tea.

Daowu asked him, “Who are you making tea for?”

Yunyan said, “There’s someone who wants it.”

Yunyan said, “Why don’t you let him make it himself?”

Yunyan said, “Fortunately, I’m here to do it.”

Once, when Yunyan was sweeping, Daowu said to him, “Too hurried!”

Yunyan said, “You should know that there is a something that is not hurried.”

Daowu said, “In that case, is there a second moon?”

Yunyan held up the broom and said, “What moon is this?”

Daowu then went off. (Xuansha heard about this and said, “Exactly the second moon.”)

After becoming an abbot, Yunyan addressed the monks, saying, “There is the son of a certain household. There is no question that he can’t answer.”

Dongshan came forward and asked, “How many classic books are there in his house?”

Yunyan said, “Not a single word.”

Dongshan said, “Then how can he be so knowledgeable?”

Yunyan said, “Day and night he has never slept.”

Dongshan said, “Can he be asked about a certain matter?”

Yunyan said, “What he answers is not spoken.”

Zen master Yunyan asked a monk, “Where have you come from?”

The monk said, “From Tianxiang [‘heavenly figure’].”

Yunyan said, “Did you see a buddha or not?”

The monk said, “I saw one.”

Yunyan said, “Where did you see him?”

The monk said, “I saw him in the lower realm.”

Yunyan said, “An ancient buddha! An ancient buddha!”

During [the year 841] Yunyan became ill. After giving orders to have the bath readied he called the head of the monks and instructed him to prepare a banquet for the next day because a monk was leaving. On the evening of the twenty-seventh of the month he died. His cremated remains contained more than a thousand sacred relics that were placed in a stone stupa. Yunyan received the posthumous title “Great Teacher No Abode.”

Jün-jen Tan-seng összegyűjtött mondásaiból

Fordította: Terebess Gábor

Folyik a híd, Officina Nova, Budapest, 1990, 84-85. oldal

– Ki hallja meg az élettelen tárgyak tanítását? – kérdezte Tung-san [Tung-san Liang-csie, 807-869].

– Az élettelen tárgyak – mondta Jün-jen.

– És tisztelendőséged hallja?

– Én nem, mert akkor te se hallanád a tanításomat!

– Miért ne hallanám?

Jün jen felemelte a légycsapóját:

– Hallod?

– Nem.

– Ha engem se hallasz, hogy hallanád az élettelen tárgyak tanítását?

Tung-san írt egy tanverset és bemutatta a mesternek:

„Ó, milyen furcsa, milyen csodás!

Az igaz hallás nem fül-hallás,

A tárgyak szavát fel nem foghatod,

Csak ha a szemeddel hallgatod.”

Tung-san még némi kétséggel terhelten távozott Jün-jentől. Útközben, ahogy átkelt egy patakon, meglátta saját tükörképét a vízben. Hirtelen megvilágosult, és boldogan énekelte:

„Egyedül járok, és mindenütt szembe jő,

Ő az, aki vagyok, én mégse vagyok Ő.”