SZÓTÓ ZEN SŌTŌ ZEN

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

A ZEN KOLOSTOR ÜTŐHANGSZEREI

鳴物 Narashimono

Percussion Instruments at Buddhist Temples

The various sound-producing implements (bells, clappers, gongs) used in a monastery to signal the times for various activities.

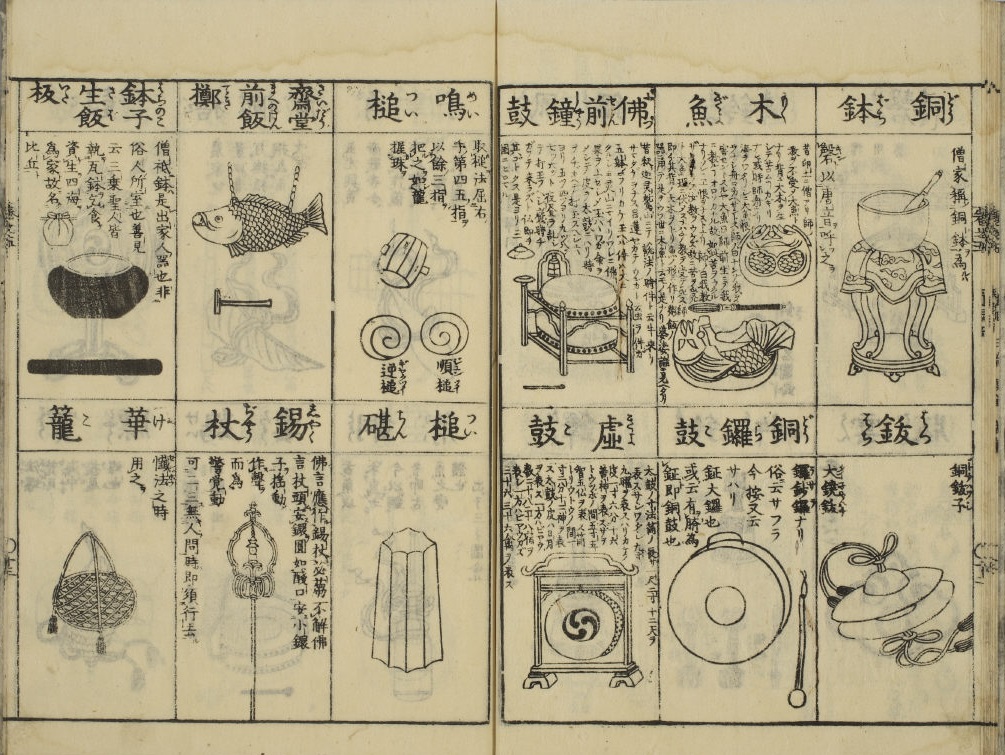

Butsuzō-zu-i 仏像図彙 Collected Illustrations of Buddhist Images. Published in 1690 (Genroku 元禄 3)

The Way of Eiheiji: Zen-Buddhist Ceremony (HTML)

https://sousei.gr.jp/1530/

https://sousei.gr.jp/downloads/1538/

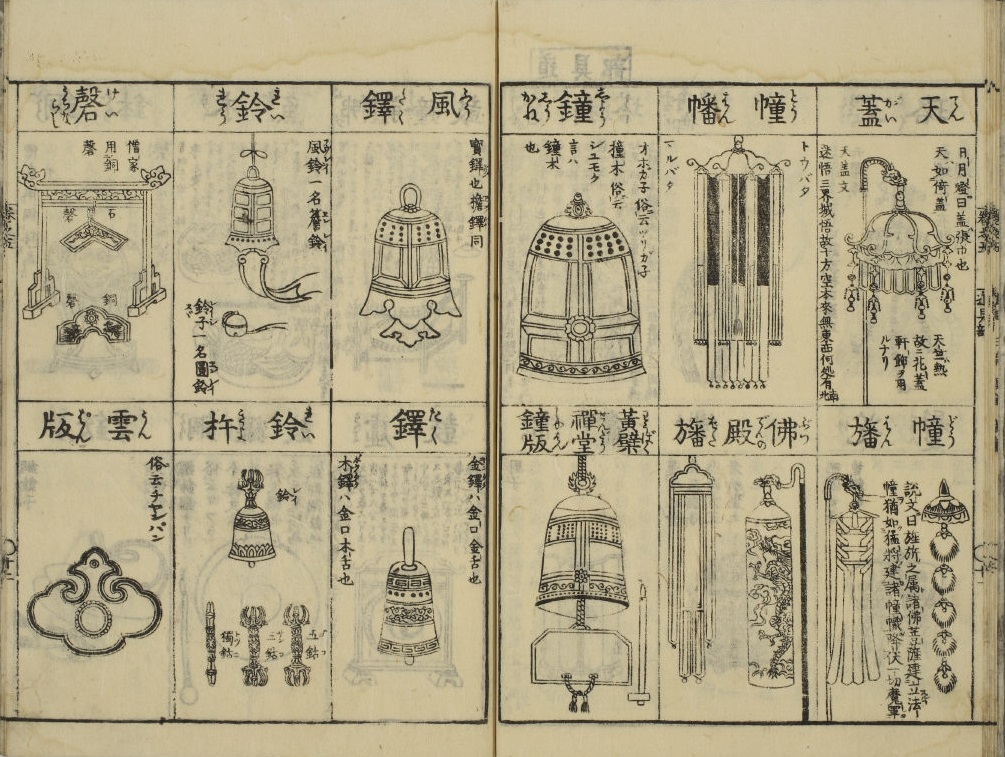

Musical Instruments

1) Bells. The largest of the monastery bells is the 大鐘 daishō, or 大鐘 ōgane, which is generally made from cast bronze and hangs in a separate structure, the 鐘樓 shōrō. Smaller versions of the same style of bell include the 殿鐘 denshō, which hangs outside the Buddha hall, and the 喚鐘 kanshō, which sits outside the master's quarters.

2) Drums. 太鼓 Taiko drums, called 法鼓 hokku in a Zen context, are found in the Buddha hall. These large instruments rest horizontally on wooden platforms and may be played at both ends using wooden sticks. Another drum-like instrument found in monasteries is the wooden 木魚 mokugyo, carved in the shape of a fish.

3) Gongs. One style of Buddhist gong is shaped like a bowl, typically made from cast bronze. Gongs rest on pillows, supported by a wooden stand, and are sounded by striking the rim with a padded stick. In Zen monasteries, the larger version is called 磬子 keisu and the smaller 小鏧 shōkei. There are also large wooden gongs, known as 梆 hō, which are carved in the shape of a fish with a pearl in its mouth.

4) Sounding Boards. There are basically two styles of sounding boards, the metal 雲版 umpan and the wooden 板 han. These boards are found throughout monastery grounds, hanging outside nearly every structure.

5) Small Hand Instruments. A variety of hand-held instruments that resemble tiny bells or gongs include the suzu, the 鈴 rei, and the 引鏧 inkin. There are also wooden clappers called 拍子木 hyōshigi.

Source: Helen J. Baroni. The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Zen Buddhism

鳴鐘の偈 Meishō no ge

Verse for Bell Ringing

三途八難 sanzu hachi nan

息苦停酸 sok-ku jo san

法界衆生 hok-kai shujō

聞聲悟道 mon sho godō

May living beings of the dharma realms,

stifled and mired in bitterness

in the three painful destinies and eight hardships,

hear the sound and awaken to the way.

The Sound Instruments in the Zen Monastery

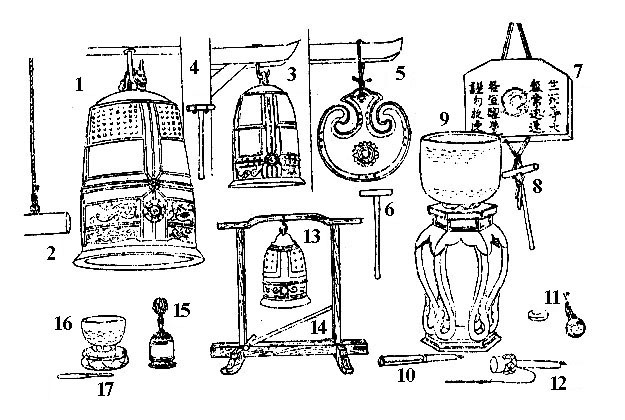

In the Zendo life, the movements of the monks on various occasions are directed by the use of different kinds of sound-producing instruments. No oral orders are given; but when a certain instrument is sounded, the monks know what it means at that particular time. The accompanying pictures illustrate such instruments.

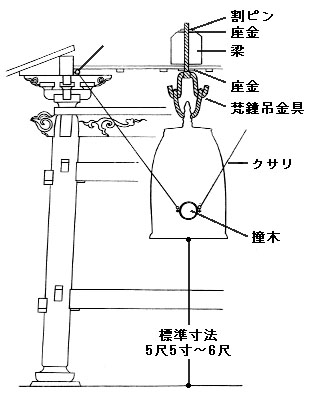

The 大鐘 Ōgane (1) is the largest bell used in the monastery, it hangs underneath a specially-designed structure. The heavy swinging beam (2, 撞木 shumoku) is used to strike the bell. It is this bell which reflects the spirit of the Buddhist temple. The ring has a peculiarly soul-pacifying effect. Lafcadio Hearn in his Unfamiliar Japan, Vol. I refers to the "big bell of Engakuji" and most beautifully describes its "sweet billowing of tone" when it is struck and the "eddying of waves of echoes" which rolls over the surrounding hills. As a work of art the bell occupies an important position, and there are many old bells now in Japan which are classed as "national treasures" of the country.

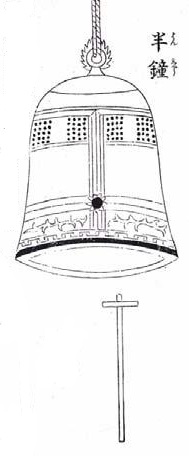

殿鐘 Denshō or 半鐘 Hanshō (3) is a much smaller one and generally found hanging under the eaves. It is struck with a mallet (4 木槌 kizuchi). When a gathering takes place in the Buddha-hall, this calls out the monks from the Zendō.

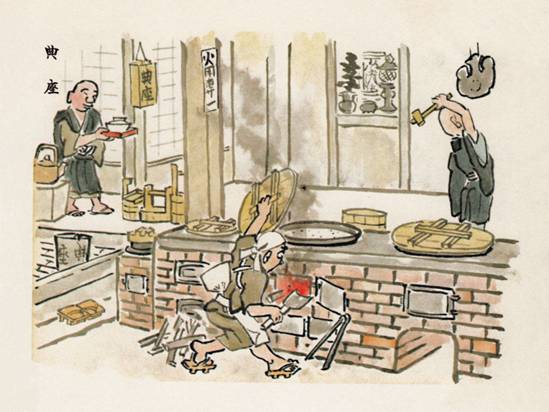

雲版 Umpan (5) is "cloud-plate" made of bronze. When this rings, it means that the dining room is open.

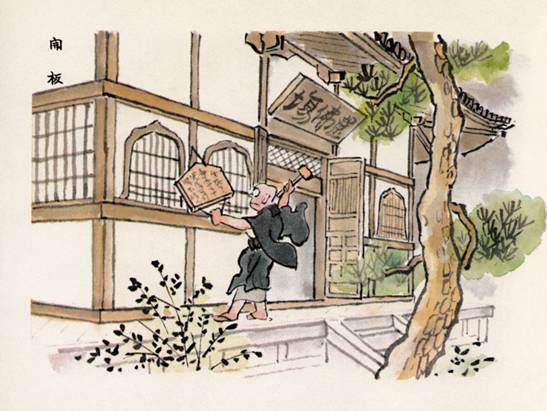

板 Han (7) is a heavy solid board of wood hung by the front door of the Zendo. When this is struck, the monks know that the time is come for them to get up or to retire to bed or that a teishō is to take place, etc. The characters read:

"Birth-and-death is the grave event ,

Transiency will soon be here,

Let each wake up [to this fact],

And, being ever reverend, do not give

yourselves up to dissipation."

The last two lines sometimes read differently in different Zendos. The board is taken hold of, when struck, by means of the strings hanging below in a loop.

鏧 Kei or 磬子 Keisu (9) is a high, somewhat large, metal gong in the Buddha-hall. Its rim is struck with a stick (10) to punctuate the sutra-reading. The smaller one, 鈴 Rin or 小鏧 Shōkei (16), is also used in this connection.

Two kinds of bells (鈴 suzu or rei) used by Rōshi are shown in (11). The choice is individual. Other kinds are also used, one of which is given in (15).

引鏧 Inkin (12) is always carried in the hand and struck with a metal stick attached to it with a string. When the head-monk strikes it in the Zendo, it means the beginning or the end of the meditation hours. When he does so at the head of a procession it means that all the monks joining it are to stand still and then sit, or that they have to rise from the sitting position and walk back to the Zendo.

喚鐘 Kanshō (13) is used when the monks want to interview the Rōshi on Zen. When the sanzen hour comes, the Rōshi's attendant strikes this bell with the hammer (14). The monks come out of the Zendo, one by one if it is a dokusan , and in file if it is a sōsan ; they sit before the bell in the order of arrival. The master interviews one monk at a time. Being ready, he rings his hand-bell (11) to which the monk responds by striking his bell (13), once for sōsan and twice for dokusan .

鈴 Rei (15), also called Rin , is a hand-bell which rings by shaking. It is used by Rōshi, and also by a monk when he reads the sutras while standing, for instance, before Idaten, the kitchen god, at meal-time.

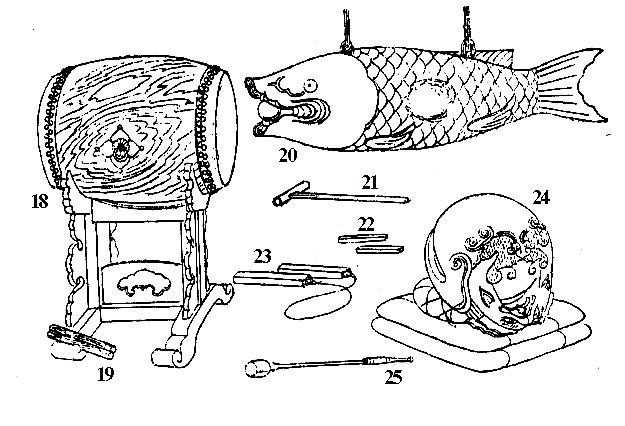

The big drum, 法鼓 Hokku (18), is generally set up on a high stand in a corner of the Buddha-hall. When a general gathering takes place, it is beaten with two sticks (19) alternately with a peculiar rhythm.

The big wooden fish (20) called 梆 Hō is used principally in the Sōtō monastery and not in the Rinzai. The inside is hollowed out. It is used to announce the midday meal. How the fish came to function in the Buddhist temple is unknown. Some think the fish is a symbol of immortality, and for this reason it is frequently found in Christian symbolism. But Buddhism is the teaching in which rebirth and not individual immortality is emphasised.

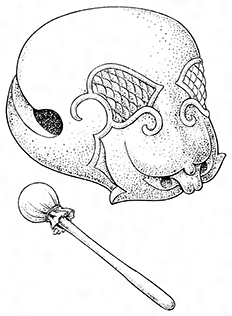

木魚 Mokugyo (24), literally "a wooden fish" is said to be the modification of the 梆 Hō (20). It is a peculiarly-shaped roundish solid block of wood with the inside hollowed out, and obtainable in all sizes, the smallest being as small as one inch on its longer side while the larger ones may measure even more than three feet. It has a fish-scale pattern on its body and where it tapers off into the form of a handle, a pair of eyes is carved. It is beaten with a stick, the top part of which is stuffed and wrapped with leather (25). The sound thus emitted has a strange hypnotic effect on the hearer. When it accompanies the sutra-reading, for example, before a teishō, it makes the minds of the audience properly receptive for what is to come.

There are two kinds of clappers, 拍子木 Hyōshigi (22 and 23) in use in the monastery. They are solid pieces of hard wood: the larger ones may be somewhat longer than one foot in length and the smaller ones about half a foot. The latter are used in the Zendo while the former are used outside, for instance, when the monks are about to eat, when the bath is ready, and on other occasions.

1. 大鐘 ōgane (nagyharang, kötélen hintázó fagerendával szólaltatják meg)

2. 撞木 shumoku (ütőrönk)

3.

殿鐘

denshō /

半鐘

hanshō (harang)

4. 木槌 kizuchi fakalapács

5. 雲版 umpan (bronz felhő-gong)

6. 木槌 kizuchi fakalapács

7. 板 han (deszkagong, függő fatábla)

8. 木槌 kizuchi fakalapács

9. 鏧 kei / 磬子 keisu (üstgong, talpas állóharang)

10. verő

11.

鈴

suzu / rei (csengő)

12. 引鏧 inkin (kézi vagy csészegong)

13. 喚鐘 kanshō (ütős harang)

14. 木槌 kizuchi fakalapács

15.

鈴

rei / rin (kézi csengettyű)

16.

鈴

rin / 小鏧 shōkei (kis állóharang)

17. ütő

18. 法鼓 hokku (nagy hordódob)

19. 枹,

桴

bachi ütőpár

20. 梆 hō (nagy fahal-gong)

21. 木槌 kizuchi fakalapács

22-23. 拍子木 hyōshigi (csapó-pár, fa csattogtató)

24. 木魚 mokugyo (fahal, kámforfából kivájt dob)

25. 棒 bō bőrfejű ütő

Source: D.

T. Suzuki THE TRAINING OF THE ZEN BUDDHIST MONK

The Eastern Buddhist Society, Kyoto, 1934

引鏧 / 印金 inkin

hand gong

csészegong

12 cm in diameter, grip painted red, 1 or 2 cushions, metal fittings and metal sticker

The handbell used by the jikijitsu to signal the beginning and ending of meditation, and for other miscellaneous purposes.

木魚 mokugyo

wooden fish

serves to keep the rhythm during sutra chanting

(kínai: muyu; koreai:

목탁

moktak; tibeti: shingnya)

木魚の棒 mokugyo no bō, a mallet used to bong the gong

"fahal"-dob

Ode to the Wooden Fish and Drum

by 趙州從諗 Zhaozhou Congshen (778–897)The four great elements come from he who built them,

It has a voice born from the emptiness inside.

They are averse to speaking to ordinary people

Only because the notes of the scale are different.

The general chanting in the sutra hall is accompanied by a wooden instrument called mokugyo. Its opening in the front resembles the mouth of a fish with two round openings on either corner of the mouth. The mokugyo rests on a handle that traditionally is carved in a way that two dragonheads hold a sphere in their mouth. The skin of the dragons extends into the mainbody of the instrument. The mokugyo is struck with a wooden mallet that has a leather covered spherical head on its end. Often a dedication of the donating individual or organization can be found on the fringe of the fishmouth.

There are different patterns of drumming; starting slow, speeding up, and slowing down in the end. Some texts are accompanied by a constant beat. However, there is one character per beat - this mostly means one syllable, sometimes two per beat. The mokugyo is played by the Densu or his/her helper.

In the zendo there is a small handheld mokugyo that is played by the Jikijitsu's helper or the Shoji.

Made from camphor wood / Cushion : gold-brocaded satin damask

To make a mokugyo, they carve wood into a large bell, drill a hole through the center, and cut out a substantial part of the interior with a lathe. There is a nice oil finish applied to the surface in the end.

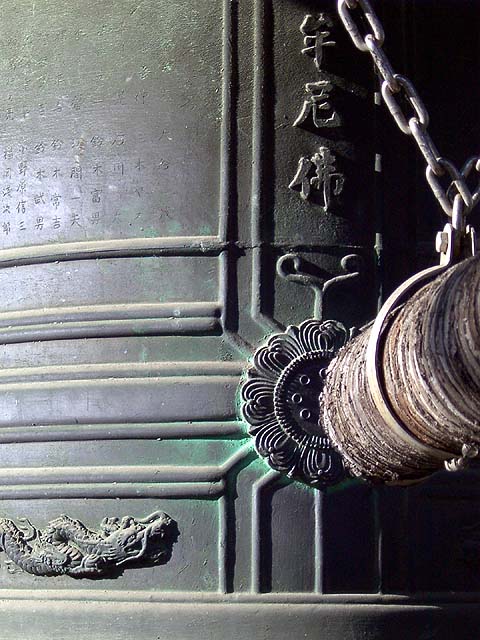

梵鐘 bonshō

大鐘

ōgane

釣り鐘 tsurigane

large temple bell

templomi nagyharang

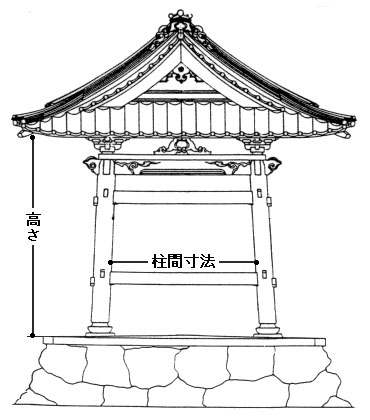

鐘樓 kane rō

bell tower, haranglábbell tower (shōrō 鐘樓), also called shūrō; kanetsukidō 鐘突堂; lit. bell hitting hall; tsuriganedou 釣鐘堂. Belfry. A building in which a bell bonshō 梵鐘 is hung.

The word "tower" (rō 樓) originally meant a structure at least two stories high. In the Chinese Buddhist monasteries of the Song and Yuan dynasties, on which medieval Japanese Zen monasteries were modeled, there often was a tower that held a great bell (daishō 大鐘) on its second floor, which had a roof but no walls. A few such buildings can still be found at large Zen monasteries in Japan today, but most bell towers consist simply of a roofed scaffolding from which a large bell and external striking beam is suspended. The structure stands on a low stone pedestal, which the person ringing the bell steps up onto.撞木 shumoku

wooden bell hammer, ütőrönkbell (kane 鐘)

Buddhist temple bells in East Asia are cast bronze bowls, ranging in size from about 20 centimeters to as much as 2 meters in diameter, which are hung mouth down from some sort of frame, scaffolding, or bar. All bells are struck externally, the smaller ones with a wooden mallet, the larger ones with a wooden beam that is suspended on one side by ropes. In the daily life of a monastery various bells are used to signal the time and the start of particular activities. The reverberation of large temple bells, which can be heard at a great distance, are also understood (literally and metaphorically) as a means of spreading the dharma.

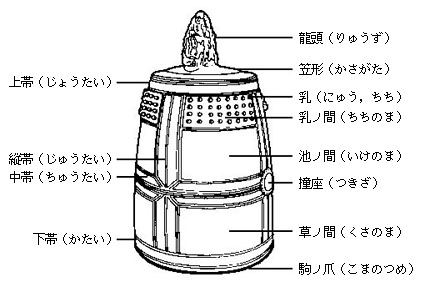

There are several parts to a temple bell:

The suspension loop (ryuzu) is formed by two dragon heads and a flame; the upper third contains nipples (nyu), a symbol of fertility, and the barren field below (ikenomachi) provides a place for poetry or iconography. The chrysanthemums, a symbol of longevity and happiness, form the striking surface (shuza).

The bonshō is derived from the bianzhong (henshō 編鐘).

法鼓 hokku

dharma drum; large drum

The large temple drum beaten to signal the beginning of teisho or a ceremony.

These large instruments (in the Buddha hall) rest horizontally on wooden platforms and may be played at both ends using wooden sticks.

Korean: 법고 beopgo

nagy hordódob

振鈴 shinrei

磬子, 鏧子 keisu

bronze bowl bell

üstgong, talpas állóharang

- A type of bell, traditionally made of a thin sheet of copper beaten into the shape of a bowl, which rests mouth up on a cushion and is rung by striking the lip with a baton. The smallest bowl bell is the so-called hand–bell (shukei 手鏧, inkin 引鏧), which is affixed to the end of a wooden handle by a bolt that runs through the bottom of the bowl and the cushion; the bell is rung by holding the handle in one hand, grasping a thin bronze rod (attached to the handle by a string) in the other hand, and striking the lip of the bowl. The small bowl-bell (shōkei 小鏧) is a medium-sized bowl, about 20 cm in diameter, that sits on a cushion and is rung with a wooden baton. Large bowl-bells (daikei 大鏧) range from 30 cm to more than 50 cm in diameter; they sit on a cushion and are rung with a wooden baton covered in leather. When any bowl-bell is rung, it reverberates for long time unless it is damped (osaeru 押さえる) by grabbing the lip with the hand or holding the baton against it. Another technique for sounding a bowl-bell is to damp it with one hand while striking it with the butt of the baton, held in the other hand. This is called "hitting damped bowl-bell with butt of baton" (nakkei 捺鏧).

- The keisu and its smaller rendition (shōkei) are gongs in bowl shape. The rim is thicker on the inside, which allows for a lower sound. The keisu is struck from the outside at the rim. The striker is wooden, half of it is covered with a thin layer of leather, the handle is usually covered with red lacquer. The large gong is struck before the chanting starts, the smaller gong is struck during the chanting. It demarks parts and especially important places in the chanted text. The Ino, who leads the chanting, strikes the keisu.

- In the zendo the chanting is led by the Jikijitsu. Instead of the Keisu the Inkin, a handheld bell, is used.

磬子 keisu

large bowl-bell

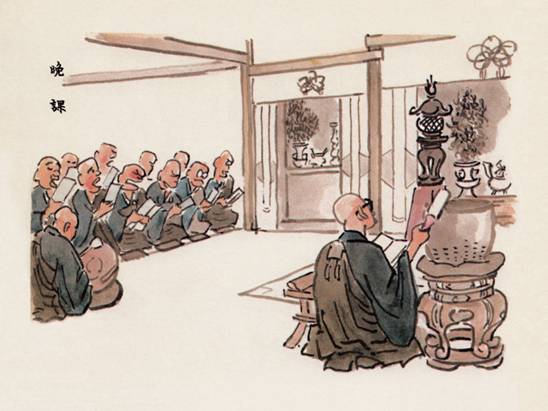

Watercolor sketch by 佐藤義英 Satō Giei (1921-1967) at 東福 寺 Tōfuku-ji, Kyoto, 1939

小鏧 shōkei

small bowl-bell

柝 taku

拍子木

hyōshigi

戒尺 kaishaku

wooden clappers, sounding sticks

tapsolófa (csapó-pár, fa csattogtató)

Length: 24 cm, 15 cm.

Material: 紫檀 red sandalwood.

木柝 A set of clappers

Material: 材質/鉄刀木 (タガヤサン)

tagayasan hard wood

板 han

木版 moppan

巡照板 junshō-ban

wooden gong

deszkagong, függő fatábla, a zazen kezdetét (木槌

kizuchi) fakalapáccsal dobolják ki rajta

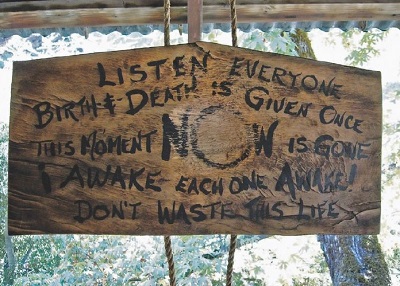

A wooden sounding board (han) which is struck to announce various daily activities in the monastery. The inscription on it reads, 『生死事大 無常迅速 各宜醒覺 愼勿放逸』 "No one knows when death will occur; it may be much sooner than one expects. Therefore we should practice Buddhism without wasting even a moment of time in order that we may discover the true meaning of life."

Birth and death are important things.

Make use of every moment.

Everything changes quickly.

Time does not wait for humans.or

Respectfully I appeal to you:

Each of us must clarify

The great matter of life and death

Time passes swiftly

Do not be negligentor

1.

Listen well everyone

Great is the problem of Life and Death

Now forever gone gone

Awake awake each one

Don't waste your life!**Shunryu Suzuki-roshi's translation is: "Don't goof off!"

2.

Listen, everyone.

Birth and death is given once.

This moment now is gone.

Awake each one awake.

Don’t waste this life.

Tassajara zendoThe han is struck three times a day. The first time at daybreak, secondly in the evening, and finally during the closing ceremony. A wooden mallet is used to strike the familiar 7-5-3 pattern with the accelerating rolls in between. The sound is harsh and somewhat unsetteling, trying to remind us of the very reasons we came to study Zen.

In Japan monks hit the han with all their strength, just like they try with their whole being to get through all the delusions and attachments. Traditionally when the han finally shows a hole in the middle the monks have the day off, until a new board is hung.

Kaihan 開板 = Striking of the wooden han.

Watercolor sketch by 佐藤義英 Satō Giei (1921-1967) at 東福 寺 Tōfuku-ji, Kyoto, 1939

萬福寺の巡照板 Junshō-ban in Manpuku-ji

The words written on the 巡照板 junshō-ban, are as follows:謹白大衆 Kin Pe Da Chon

生死事大 Sen Su Sū Da

無常迅速 Ū Jan Shin So

各宜醒覚 Kō Gi Shin Kyo

慎勿放逸 Shin U Fua NiSincerely I announce to the great assembly:

Live and death are matters of great importance!

Everything is vain and passes by quickly!

Everybody may achieve awakening quickly!

Guard yourselves and do not waste this live with vanity!Translated by Tobias Eckerter

In: One year in Manpuku-ji The Monastery of the Ten Thousand Blessings

Japanese Religions, Spring and Fall 2013, Vol. 38 (1 & 2): 97-112

Drawing & text below image by Mark T. Morse (1973-)

One of my memories of a Zen monastic day is the morning and evening striking of the Han. A Han is a large wooden slab that hangs outside of the meditation hall. It would be struck with a wooden mallet in a cascading rhythm. Contrasted with the stillness and dark of the morning or evening the sound is dramatic. Kind of like mixing thunder, wood chopping, and a machine gun. Over the life of the Han it develops an indentation at the center from the daily use. I was once told that it was an invitation to a fierce dragon to spurn on the practitioners. Closing the day with the Han would send the dragon home for the night. A Han is inscribed with an ink brush phrase, which there are many variations of but it goes something like:Great is the matter of birth and death

Life flows quickly by

Time waits for no one

Wake up! Wake up!

Don't waste a moment!

五家 鐘板 Wu jia zhong ban - Bells and the Five Houses' gong shapes

A csan buddhizmus öt háza (iskolája, felekezete) mindegyike saját deszka-gong formát használt: a Lin-csi iskola fekvő téglalap alakot, a Cao-Tung álló téglalapot, a Fa-jen háromszöget, a Kuj-Jang körszeletet, a Jün-men pedig nyolcszögű korongot.

The Five Houses of Chan (五家) (also called Five Schools of Chan) were the five major branches of Chan Buddhism that arose in Tang dynasty China. The five houses were the Linji (臨濟宗), Caodong (曹洞宗), Fayan (法眼宗), Guiyang school (潙仰宗), and Yunmen (雲門宗) branches, each named after their respective Chan masters.

魚板 / 魚版 gyoban

魚鼓 gyoku

梆 hō

fish drum

nagy fahal-gong

Gyoban is a wooden fish-shaped drum, hollow inside, which serves as a signal to start and end rituals, meditation sessions and meals. The fish-shaped drums are common in Zen temples in Japan. Gyoban is also called Gyoku, Mokugyoku, or Hō. In Buddhism, the fish, which never sleeps, symbolizes wakefulness and devotion to training.

雲版 unpan, umpan

磬 kei

flat bronze panel-gong

bronz felhő-gong

- An umpan is a flat gong, usually bronze, which is rung at mealtime in a Zen monastery. Literally translated as "cloud plate," the umpan is also sounded to "signal other events," such as a call to the conclusion of zazen. Typically one will find an umpan outside the kitchen (J. kuri) or dining hall area. According to Helen J. Baroni, "Wooden boards (han) hanging on various buildings throughout the temple grounds are sounded simultaneously to alert the members of the community beyond the range of the umpan."

- A cast iron "sounding board" or "gong" (han 版) hung near the kitchen in Zen monasteries; although it is basically flat, it has the stylized shape of a "cloud" (un 雲) as those are depicted in East Asian Buddhist paintings.

Watercolor sketch by 佐藤義英 Satō Giei (1921-1967) at 東福 寺 Tōfuku-ji, Kyoto, 1939

喚鐘 kanshō

半鐘 hanshō

殿鐘 denshō

small bells

of various sizes (usually struck with a small mallet while chanting sutras, or used in a temple to signal the time for convocation)

kisharang

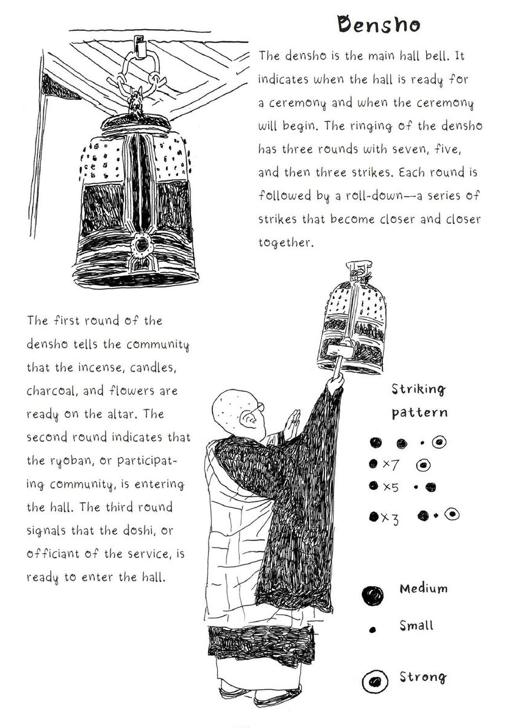

Denshō (Main Hall Bell)

The bell installed in the main hall is called the denshō. It is rung to announce the beginning of a ceremony or to assemble the participants. Using a wooden mallet, a monk rings the bell gently and slowly first, then gradually speeds up. Usually, there are three rounds of tolling. The end of the first round indicates that the main hall is ready for the service. Then, the end of the second round indicates that all the officiating monks have gathered in the hall. Finally, the end of the third round indicates that the officiant is ready to enter the main hall.

Kanshō 喚鐘 = The small hanging bell rung by the monks to signal entrance to the master's room during dokusan. It has thus come to be synonymous with sanzen itself.

鐃鉢 nyōhachi

cymballs

cintányér