ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

明峰素哲 Meihō Sotetsu (1277-1350)

Meihō Sotetsu: Zazen

Translated by Lucien Stryk & Takashi Ikemoto,

In: ZEN: Poems, Prayers, Sermons, Anecdotes, Interviews,

Anchor Books, Doubleday & Co., Inc., Garden City, New York, 1963, pp. 56-58.

Meiho, fifth patriarch of the Japanese Soto sect,

spent eight years disciplining himself under Keizan.

He gained satori while grappling with the koan,

"What is it that makes all things wax and wane?" He

then deepened his Zen under other masters, finally

retuming to Keizan and succeeding him. He scorned

all gain and fame, and urged his disciples to devote

themselves to Zen-sitting alone. The folIowing sermon

is one of the best-known writings on zazen ever done

by a Japanese.

Zazen

Zen-sitting is the way of perfect tranquillity: inwardly

not a shadow of perception, outwardly not a

shade of difference between phenomena. Identified

with yourself, you no longer think, nor do you seek enlightenment

of the mind or disburdenment of illusions.

You are a flying bird with no mind to twitter, a mountain

unconscious of the others rising araund it.

Zen-sitting has nothing to do with the doctrine of

"teaching, practice, and elucidation" or with the exercise

of "commandrnents, contemplation, and wisdom."

You are like a fish with no particular design of remaining

in the sea. Nor do you bother with sutras or ideas.

To control and pacify the mind is the concern of lesser

men: Sravakas, Pratyeka-Buddhas, and Hinayanists.

Still less can you hold an idea of Buddha and Dharma.

If you attempt to do so, if you train improperly, you

are like one who, intending to voyage west, moves east.

You must not stray.

Also you must guard yourself against the easy conceptions

of good and evil: your sole concern should be

to examine yourself continually, asking who is above

either. You must remember too that the unsullied essence

of life has nothing to do with whether one is

priest or layman, man or woman. Your Buddha-nature,

consummate as the full moon, is represented by your

position as you sit in Zen. The exquisite Way of Buddhas

is not the One or Two, being or non-being. What

diversífies it is the limitations of its students, who can

be divided into three cIasses -- superior, average, inferior.

The superior student is unaware of the coming into

the world of Buddhas or of the transmission of the non-

transmittable by them: he eats when hungry, sleeps

when sleepy. Nor does he regard the world as himself.

Neither is he attached to enlightenment or illusion.

Taking things as they come, he sits in the proper manner,

making no idle distinctions.

The average student discards all business and ignores

the external, giving himself over to self-examination

with every breath. He may probe into a koan, which he

puts mentally on the tip of his nose, finding in this way

that his "original face" (fundamental being) is beyond

life and death, and that the Buddha-nature of all is not

dependent on the discriminating intellect but is the un-

conscious consciousness, the incomprehensible understanding:

in short, that it is clear and distinct for alI

ages and is alone apparent in its entirety throughout

the universe.

The inferior student must disconnect himself from

all that is external, thus liberating himself from the duality

of good and evil. The mind, just as it is, is the

origin of all Buddhas. In zazen his legs are crossed so

that his Buddha-nature will not be led off by evil

thoughts, his hands are linked so that they will not take

up sutras or implements, his mouth is shut so that he

refrains from preaching a word of dharma or uttering

blasphemies, his eyes are half shut so that he does not

distinguish between objects, his ears are closed to the

world so that he will not hear talk of vice and virtue,

his nose is as if dead so that he will not smell good or

bad. Since his body has nothing on which to lean, he is

indifferent to likes and dislikes. He negates neither being

nor non-being. He sits like Buddha on the pedestal,

and though distorted ideas may arise from him, they do

so idly and are ephemeral, constituting no sin, like reflections

in a mirror, leaving no trace.

The five, the eight, the two hundred and fifty commandments,

the three thousand monastic regulations,

the eight hundred duties of the Bodhisattva, the Buddha-

nature and the Bodhisattvahood, and the Wheel of

Dharma -- all are comprised in Zen-sitting and emerge

from it. Of all good works, zazen comes first, for the

merit of only one step into it surpasses that of erecting

a thousand temples. Even a moment of sitting will enable

you to free yourself from life and death, and your

Buddha-nature will appear of itself. Then all you do,

perceive, think becomes part of the miraculous Tathata-

suchness (true nature, thusness).

Let it be thus remembered that tyros and advanced

students, learned and ignorant, all without exception

should practice zazen.

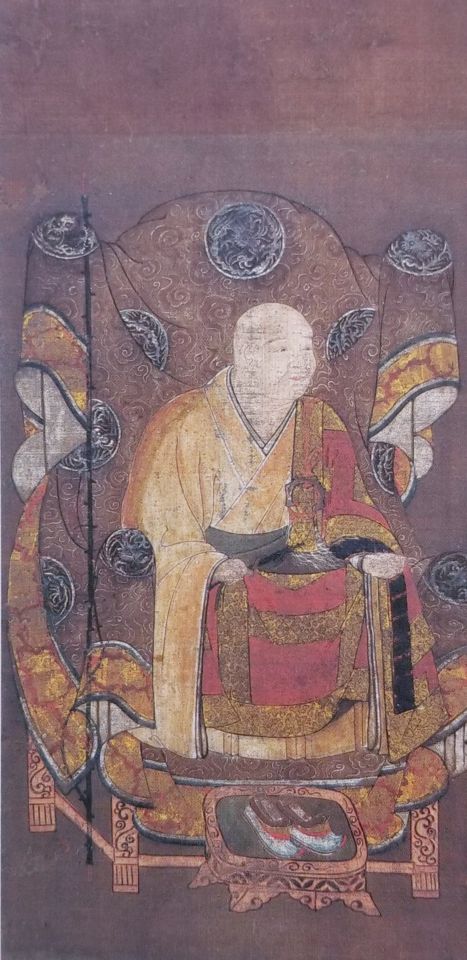

木造明峰素哲坐像 (石川県永光寺所蔵)

木像 mokuzō; wooden effigy of Meihō

永平道元 Eihei Dōgen (1200-1253)

孤雲懐奘 Koun Ejō (1198-1280)

徹通義介 Tettsū Gikai (1219-1309)

螢山紹瑾 Keizan Jōkin (1268-1325)

Meihō-ha 明峰派

Hata’s lineage

明峰素哲 Meihō Sotetsu (1277-1350)

珠巌道珍 Shugan Dōchin (?-1387)

徹山旨廓 Tessan Shikaku (?-1376)

慶屋定紹 Kei’oku Teishō (1339–1407)

柏巖樹庭 Hakugan Jutei

玄室智玄 Genshitsu Chigen

東林暾 Tōrin Ton

茂林善榮 Morin Zen’ei

竹堂慧巖 Chikudō Egen

學海性文 Gakukai Shōbun

天怡道悅 Ten’i Do’etsu

怡山文悅 Gisan Mon’etsu

育翁道養 Iku’ō Dōyō

通山慧馨 Tsūzan Ekei

快壽山悅 Gaiju San’etsu

朝山永暾 Chōzan Eiton

謙巖寂英 Kengan Jaku’ei

玉巖懶牛 Gyokugan Raigyū

朝雲喝宗 Chō’un Katsusō

雷洲大震 Raishū Daishin

單山良傳 Tanzan Ryōden

機外默禪 Kigai Mokuzen

默淵慧安 Mokuen E’an

太梅慧芳 Taibai Ehō

默道慧昭 Mokudō Esshō

明峰慧玉 Meihō Egyoku (1896-1985)

→ [秦 Hata, 76th Abbot of Eihei-ji]

Tokuō's lineage

明峰素哲 Meihō Sotetsu (1277-1350)

珠巌道珍 Shugan Dōchin (?-1387)

徹山旨廓 Tessan Shikaku (?-1376)

桂巌英昌 Keigan Eishō (1321-1412)

籌山了運 Chuzan Ryōun (1350-1432)

義山等仁 Gisan Tōnin (1386-1462)

紹嶽堅隆 Shōgaku Kenryū (?-1485)

幾年豊隆 Kinen Hōryū (?-1506)

提室智闡 Daishitsu Chisen (1461-1536)

虎渓正淳 Kokei Shōjun (?-1555)

雪窓祐輔 Sessō Yūho (?-1576)

海天玄聚 Kaiten Genju

州山春昌 Shūzan Shunshō (1590-1647)

超山誾越 Chōzan Gin'etsu (1581-1672)

福州光智 Fukushū Kōchi

明堂雄暾 Meidō Yūton

白峰玄滴 Hakuhō Genteki (1594-1670)

月舟宗胡 Gesshū Sōko (1618-1696)

↓

Ryōkan's lineage 徳翁良高 Tokuō Ryōkō (1649-1709) |

Teizan's lineage 徳翁良高 Tokuō Ryōkō (1649-1709) |

Harada-Yasutani's lineage 徳翁良高 Tokuō Ryōkō (1649-1709) |

Sawaki-Uchiyama's lineage 徳翁良高 Tokuō Ryōkō (1649-1709) |

Katagiri's lineage 徳翁良高 Tokuō Ryōkō (1649-1709) |

永平道元 Eihei Dōgen (1200-1253)

孤雲懐奘 Koun Ejō (1198-1280)

徹通義介 Tettsū Gikai (1219-1309)

螢山紹瑾 Keizan Jōkin (1268-1325)

Meihō-ha 明峰派

Manzan's lineage

明峰素哲 Meihō Sotetsu (1277-1350)

珠巌道珍 Shugan Dōchin (?-1387)

徹山旨廓 Tessan Shikaku (?-1376)

桂巌英昌 Keigan Eishō (1321-1412)

籌山了運 Chuzan Ryōun (1350-1432)

義山等仁 Gisan Tōnin (1386-1462)

紹嶽堅隆 Shōgaku Kenryū (?-1485)

幾年豊隆 Kinen Hōryū (?-1506)

提室智闡 Daishitsu Chisen (1461-1536)

虎渓正淳 Kokei Shōjun (?-1555)

雪窓祐輔 Sessō Yūho (?-1576)

海天玄聚 Kaiten Genju

州山春昌 Shūzan Shunshō (1590-1647)

超山誾越 Chōzan Gin'etsu (1581-1672)

福州光智 Fukushū Kōchi

明堂雄暾 Meidō Yūton

白峰玄滴 Hakuhō Genteki (1594-1670)

月舟宗胡 Gesshū Sōko (1618-1696)

↓

Morita's lineage 卍山道白 Manzan Dōhaku (1635-1715)

Kohō's lineage 卍山道白 Manzan Dōhaku (1635-1715)

Hakusan's lineage 卍山道白 Manzan Dōhaku (1635-1715) |

Otogawa’s lineage 卍山道白 Manzan Dōhaku (1635-1715)

|

Kishizawa's lineage 卍山道白 Manzan Dōhaku (1635-1715) |

Aoyama's lineage 卍山道白 Manzan Dōhaku (1635-1715) |

Itabashi's lineage 卍山道白 Manzan Dōhaku (1635-1715) |