ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

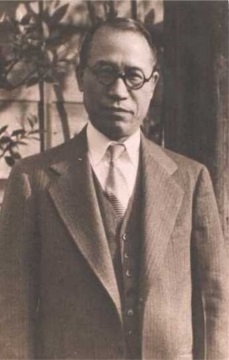

増永霊鳳 Masunaga Reihō (1902-1981)

Contents

MASUNAGA TEXTS

What is Zen

The Role of Zen in Modern Age

Western Interest in Zen

Zen and Judo

The Standpoint of Dogen and His Ideas on Time

DOGEN TEXTS

Fukan Zazengi

Genjo Koan

Bendowa

Uji

Shoji

Zenki

KEIZAN TEXTS

Zazen Yojinki

Sankon Zazen Setsu

*

Tung-shan Liang-chieh (807-869). Hōkyōzanmai

Translated by Masunaga Reihō

Shih-t'ou Hsi-ch'ien

(700–790). Sandōkai

Translated by Masunaga Reihō

Shushōgi

Translated by Masunaga Reihō

PDF: Reiho Masunaga, A Primer of Sōtō Zen; a translation of Dōgen's Shōbōgenzō zuimonki,

[The present translation is based on the standard version by Menzan Zuihō as edited by Watsuji Tetsurō]

Honolulu, University of Hawaii: East-West Center Press, 1971, 1978, 119 p.

London and Henley: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1972.

Zen for Daily Living

by Reihō Masunaga

Shunjusha Publishing Co., Kanda, Tokyo, 1964.

About the Zen teacher - Prof. Masunaga Reiho

(From Danny Waxman book: 'Zen Questions and Answers')

http://www.zenki.com/index.php?lang=en&page=aboutMasunaga

Q : Who was your Zen teacher?

A : My Zen teacher was Prof. Masunaga Reiho (1901-1980). He understood Dogen's Shobogenzo, and introduced Dogen's Zen to the modern world. Prof. Masunaga taught that everyone must and can find himself through Zazen (the calm sitting with crossed legs). Zen, he said, brings the means for releasing the vital moment in everyone, and makes creative altruism a natural behavior. As to the question - How can Zen flourish in the modern world? His answer is: raw Zen, simple, just a quiet sitting. The trainee can't hide or close himself off the world even when he is returning to himself. He must go out to the world while returning to himself. The Zen student has to solve and fulfill in his own daily life, the paradox of entering and leaving. The trainee starts his actions in the world while he or she is penetrating to the true self. The modern Zen student doesn't have the shelter and the training conditionings of the Zen monasteries. The trainee must find in himself, (through training and through the help of a true-teacher), the inner power that is needed for full functioning in the fast and stormy modern life, while still penetrating into himself.

For many years Prof. Masunaga was the vice president of Komazawa University in Tokyo. The university emphasized the studies of Buddhism and was especially focused on the Soto-Zen School. He was professor of Buddhist Philosophy and History of Zen Buddhism at Komazawa University. One of his important academic research-fields was Chinese Zen-texts. He was also one of the head priests of Eiheiji, although he was very modest about this fact. He also had a wife and three children.

His two main teachers were: the Zen teacher Ekiho Minamoto who was the head priest of Kongoin temple, and the Zen teacher Giho Okada who was the president of Komazawa University and the head of Unshoji temple.

Prof. Masunaga believed that Zen is important to the people of the West. He believed that it is possible to bridge the differences between the cultures of the West and the East through Zen training. He taught that it is necessarily to combine the good qualities of the two cultures for the progress of mankind and for creating a more humanistic world. Prof. Masunaga Reiho opened his heart to, and shared his knowledge with western trainees. Although he was a very busy man, he always had time for anyone who truly wanted to learn Zen. He was an acknowledged expert and leader of Buddhist studies in his time, and was especially strong in actual understanding of Dogen's Zen.

He studied Chinese and Indian Languages and was also very interested in western culture, thus, he studied English and German as well.

His academic and public activities included writing more than fifteen books on Zen and Buddhism and many articles (in Japanese), editing, lecturing and so on. Prof. Masunaga wanted to help the western people to know more about the Soto-Zen school, and the benefits of practicing Zazen. For this propose he wrote Zen books and articles in English. His books contain translations (from Japanese to English), of some of the most important chapters of Shobogenzo, and other Zen-texts (listed partly in the answer to the question about Shobogenzo).

Most significant are his introductions and commentaries to every text that he has translated, and many additional essays each contain information, explanations and ideas about Zen life, history and culture.

Q : How did you meet Prof. Masunaga?

A : When I came to Japan in 1958, I immediately started studying Judo and searched for a Zen teacher. I had been told that I could find a Zen teacher in a particular place in Tokyo. One of my Japanese acquaintances brought me to the door of Prof. Masunaga's house, and left. I knocked on the door, and a man of average height opened the door and asked me: What do you want?

I answered: To learn Zen. Prof. Masunaga told me: Not true. You want to find yourself. I entered inside, we sat Zazen together and he taught me some important things. From that moment and for the next 40 years until now, I study Zen and practice Zazen. When Prof. Masunaga told me: You want to find yourself. in that moment, I understood that he was a true Zen teacher. I loved him, and learned from him until the end of his life.

Books in English

Sōtō Approach to Zen, Tokyo: Layman Buddhist Society Press, 1958, 215 p.

Zen beyond Zen, Tokyo: Komazawa University, 1960, 73 p.

Zen for Daily Living, Kanda, Tokyo: Shunjūsha, 1964, 72 p.

A Primer of Sōtō Zen; a translation of Dōgen's Shōbōgenzō zuimonki, Honolulu, University of Hawaii: East-West Center Press, 1971, 119 p.

[The present translation is based on the standard version by Menzan Zuihō as edited by Watsuji Tetsurō]

What is Zen

From Zen for Daily Living by Prof. Masunaga Reiho, Shunjusha Pablishing Co., 1964.

Zen and its culture are unique to the East, and until recently the West knew little about them. Some Americans and Europeans who have learned of Zen have become deeply interested in it.

The interest stems possibly from Zens ability to communicate new life awareness. Western culture is oriented primarily toward Being; Eastern culture, toward non-Being. Being can be studied by objective logic. Non-Being must be existentially understood; it is the principle of absolute negation that enables one to loosen bonds and turn toward limitlessness.

This culture of non-Being developed in the Far East with the points of emphasis differing from country to country. In India it was pre dominantly intellectual and philosophical; in China, practical and down to earth; and in Japan, esthetic and emotional. Zen linked up with these various cultural characteristics as it spread. What then is Zen?

To define Zen is difficult. To define is to limit to make a neat conceptual package that abstracts from the whole and gives only part of the picture. This would not capture Zen, for it is rooted in our deepest life flow and deals with the facts of unfettered experience.

The non-conceptual nature of Zen is apparent in the catch phrases that became popular in Sung China. Zen trainees took their cues from such expressions as:

Zen is not bound by the words and letters of the sutras and satras. It passes from mind to mind outside the classified and systematized doctrines. Systematizing the Buddhist scriptures was a characteristic of Chinese Buddhism. But Zen basically eluded systematization. It does not lean on the classified teachings. It concentrates on penetrating to the inherent nature of man, and this is called becoming the Buddha.

Of course, Zen does not dispense with words and letters altogether. It is merely not be enslaved by them. In fact, very few religions have produced as many fresh literary works as Zen. Much of the material, naturally enough, deals with awakening from the word-bound state. This experience does not lend itself to long discourses , so Zen expressions are usually epigrammatic and poetic. One of Ummons most famous sayings was: Every day is a good day. Hoen said: When one scoops up water, the moon is reflected in the hands. When one handles flowers, the scent soaks into the robe.

From the outset Zen emphasized human dignity. This is the dignity deriving not from the ego but from the "natural face" we all have. We gain vital freedom by becoming aware of this "natural face" and living in terms of it. Technically, this makes Zen a religion of immanence, but to stop here leaves only a concept "a pictured mochi (rice-cake)."

The important thing is the actual experiencing of Zen. Such an experience would contribute significantly toward allaying the anxieties of modern man, beset as he is with the deadening impact of mass communications and the mechanical life.

Because modern man needs some sort of conceptual guideline to start out with, an effort to put Zen in sharper focus may serve a purpose. In olden times some Zen masters responded to questions with: Zen is Zen. While terse and to the point, this definition hardly offers any help to modern seekers of Zen understanding. Therefore, I venture to define Zen tentatively as follows: Zen is a practice that helps man to penetrate to his true self through cross-legged sitting (zazen) and to vitalize this self in daily life.

This definition, of course, does not cover all of Zen. But it does include the important elements. The three basic points in the definition are:

Zazen arose in ancient India. To escape the oppressive heat, Indian thinkers went into forests and hills. There they meditated under huge trees. If they stood, they tired; if they lay down, they fell asleep. So they adopted a method of cross-legged sitting with back straight.

The word Zen derives from dhyana, meaning, "to think." Human beings are a thinking animal. They are like a reed in their weakness, but they are the "thinking reed" of Pascal.

The word dhyana appears in the pre-Buddhist Upanishads . This was the form of zazen used by the Buddha, although his philosophic standpoint differed.

In China, dhyana was rendered as shii-shu (thinking practice) in the Old Translation (pre-Hsuan-tsang) and as Joryo (tranquil thinking) in the New Translation (Hsuan-tsang and after).

Joryo means calming the mind and thinking of ultimate truth. Sitting cross-legged, the Buddhist trainee considered the true meaning of the world and of human existence.

In zazen the important point is to harmonize body, breathing, and mind. The half or full paryanka posture is used. Exhaling and inhaling settle to a calm rhythm. Breathing plays a vital role; in India it is called prana, or life. To harmonize the mind is to dissolve the t perplexities and delusions that disturb our minds.

There is an orthodox and a simplified form of zazen. In the orthodox method the right foot rests on the left thigh, and the left foot on the right thigh. The left hand is placed in the right hand with palm upward. The thumbs touch and the right hand in turn rests on the left foot. The trainee sits upright on a thick cushion, leaning neither forward nor backward or from side to side. This method is described by Dogen in Fukanzazengi and by Keizan in Zazenyojinki . English translations of both are included in my Soto Approach to Zen .

In the simplified form the right foot only is put on the left thigh. The Test is the same as in the orthodox method. But even the simplified form may present some difficulties for the average Westerner. Young Japanese have trouble with it, too.

Upon completion of zazen the hands are placed over the chest with the right hand clasping the left fist A slow walk follows in half step with one breath for each step. This procedure-called Kinhin (canka in Pali) - helps to keep the mind calm and relieve the stiffness in the legs.

In zazen nothing is sought, not even enlightenment Bodhidharma called it the non-seeking practice. But the results are substantial. Repeatedly practiced zazen seems to invigorate the involuntary nervous system. It strengthens the solar plexus. Some Japanese psychologists have credited zazen with

Results of recent scientific experiments indicate that zazen also reduces the modulation of brain waves. Zazen, in short, prepares the body and mind for the next stage of vital activity.

Basic problems return to the self. It is the key to penetrating the nature of truth. The Indian Upanishads , which established the philosophy of Atman , said: All cosmos is this Atman. In Western philosophy, too, the nature of the self has fascinated thinkers. Man is the weakest reed in nature, said Pascal, but he is a thinking reed.

Rikushozan, who taught the philosophy of One Mind, said: The cosmos is my mind. My mind is the cosmos. In the depth of minds we recognize the cosmic spirit that breaks out of narrow consciousness and works naturally. We cannot doubt that the self is a thinking reed.

The self, as we ordinarily know it, is where time and space cross. In the West the conditioned self is usually accepted as it appears from the standpoint of Being. The conditioned and instinctive come with it. In the East, with its emphasis on non-Being, the conditioned self tends to be downgraded. The East would awaken to the natural and purify the instinctive.

The conditioned self includes many discrepancies and impurities. This is the self that Buddhism found unacceptable, noting that all things have no selfhood. It means that there is no fixed substance anywhere and no reason to cling to it. To postulate such a substance is the ordinary view.

The unifying element in this stream of consciousness is provisionally called the self. There is no soul without this body. Truth emerges when we can empty ourselves while observing things. To observe without dogmatic bias lies at the base of the scientific spirit. Science can flourish only so far as it stays clear of narrow dogmas, and strive for systems free from contradictions.

The idea that all things have no selfhood was supported by the Buddhist teachings of mutual dependence and impermanence. It ripened into the ideas of Buddhahood in the Mahanirvana Sutra and of the Tathagata-garba in the Srimala Sutra.

In Hinayana Buddhism, Sarvastivadin considered the mind as stained from the standpoint of realism, while Mahasanghika considered it pure from the standpoint of idealism. Mahasanghika returned to Mahayana Buddhism.

Mahayana Buddhism is a progressive movement that tries to return to the basic spirit of the Buddha in accord with the age. Mahayana scriptures see the mind of man as essentially pure. This is especially true in the Mahanirvana Sutra, which teaches that all beings have Buddha-nature and points to the inherent Buddha mind in everyone.

Buddha-nature is the ground for becoming the Buddha: it is the Religiositat of humanity and the true humanity. Faith in Buddha- nature provides the basis for enlightenment and the ultimate ground of human dignity.

In the Srimala Sutra the term used is the Tathagata-garba. It means the womb enclosing the Tathagata. All beings are said to be wrapped in the deep mind-wisdom of the Tathagata. This is called shosozo (enveloping storehouse). The mind-wisdom of the Tathagata is covered by the delusions and desires of all being. This is called ompuzo (hidden storehouse). Many Buddhists generally consider the latter as Buddha-nature. Actually the former seems closer to the truth.

Buddha-nature is the true self that manifests itself when we lose ordinary selfhood. It is the inherent self (Eigenes Selbst) of existential philosophy. To penetrate to the true self is to gain enlightenment (Satori).

In Zen some schools emphasize Satori, and others give it less weight. The Rinzai School is an example of the former; the Soto School, an example of the latter. Rinzai Zen courts Satori by reflecting on the Koan during zazen. Soto Zen does not set Satori and practice apart; it considers them self-identical. The former is convenient for the beginner, but one misstep can turn it into a gradualist sort of Zen. Soto Zen is suited for more experienced Zen trainees. But here again, a misstep can lead easily to a form of naturalism.

Dogen, who transmitted Soto-Zen to Japan, deepened the Buddha- nature concept in his essay on the subject. He did not accept the usual interpretation of the passage in the Mahanirvana sutra: All beings inherently have Buddha-nature. He read it: All beings are Buddha- nature. Dogen thus made Buddha-nature the ground of all existences and the origin of all values. All existences, he said, are the self-expression of Buddha-nature.

From this basic standpoint, Dogen extensively discussed the ideas of u-bussho (Buddha-nature as Being), mu-bussho (Buddha-nature as non- Being), ku-bussho (Buddha-nature as emptiness), setsu-bussho (Buddha-nature as expression), mujo-bussho (Buddha-nature as impermanence), and gyo-bussho (Buddha-nature as practice).

U-bussho considers all existences as Buddha-nature. Mu-bussho is the ground of form. Ku-bussho is the Buddha-nature transcending both Being and non-Being. Setsu-bussho takes all things in themselves as self-expressions of Buddha-nature. Mujo-bussho is the ever-flowing development of Buddha-nature itself. Gyo-bussho is the bodily practice of Buddha-nature.

Faith without practice lacks strength. As evidenced by such catch phrases as no dependence on words and letters and a special transmission outside the classified teachings, Zen stresses practice. The two basic forms of Zen practice are zazen and daily activity. Soto Zen especially puts strong emphasis on thorough practice in daily life, Zen practice centers on:

Living every moment to the fullest.

Engo said: In living we express full function in dying we express full function. The absolute present comes alive. When we function fully, we are vitally free. John Dewey also saw this and attributed immeasurable value to the complete experience in art and living.

Dewey' views on the use of posture reflexes as a mechanism for change may be appropriate here. In his Introduction to Dr. F.M. Alexander's The Use of The Self , Dewey stated that a man's posture, especially the way he holds his head, enables him to take possession of his own potentialities and move from conditioned enslavement into a means of vital freedom. It is interesting that Aldous Huxley, one of the best-known Western admirers of Zen, once studied with Dr. Alexander.

Transcending dualism and using it freely.

Vimalakirti talked about the non-dualistic and this is where Zen resides. So long as we cling to dualism, we face conflict and anxiety. The perfect way, Sosan said, is not difficult. Just drop discrimination. Clear and bright is the world when we neither hate nor love.

Dualistic tension between hate and love, right and wrong, good and evil makes the human being prey to rigid dogma. He cannot move freely.

Respecting the physical

Buddhism essentially denies any dualism between body and mind. Yet most Buddhist teachings tend to stress mind and consciousness. Dogen, however, held that such emphasis abstracted the human being. To gain the Way, he said, make use of your body. A faith rejecting the body becomes sterile and meaningless.

Enlarging awareness.

The nuclear and space age that we live in encourages the vigorous progress of science. But man has increasingly become obsessed with science and machines and lost touch with his essential humanity. Zen works to check this estrangement and restore intensity of awareness. If we know ourselves at all times, truth is where we stand, Rinzai said. Each morning Zuigan called: The Self! The Self! Yes, yes, he answered. He also said: Don't ever let others condition you.

Releasing natural altruistic action.

Dogen called such action benevolence and considered it a universal law benefiting oneself and others. Prof. Pitirim A. Sorokin uses the term creative altruism and sees it as a key to reconstructing man. This is reflected in the title of an important work edited by him: Forms and Techniques of Altruistic and Spiritual Growth . Non egoism and creativity go together. Creative altruism and the Bodhisattva vow are one. And this current flows through Zen as it does through the rest of Mahayana Buddhism.

Increasing serenity and effectiveness in daily life - Zazen in a quiet room carries over into daily life. Rinzai said: If hungry, eat; if tired, sleep. Daily life offers no perplexities. It is relieving your self when needed, putting on clothes, and eating food. And when tired, it is stretching out to sleep. In an increasingly mechanized world the brain often works overtime in unproductive grooves. Day-to-day pressures bring neurosis, anxiety, and various complexes. The joy of living the moment fades, and despair closes in. To many sensitive individuals today, life has gone stale. They may find in Zen a clue to a fresher approach to life. To follow up the clue will require the courage to overthrow the tyranny of learned responses. Zen serenity and real living stem from recognizing things for what they are.

The standpoint of a fully functioning Zen man was expressed by Fuke:

The Zen master thus lives serenely and sensitively in vital freedom no matter what comes.

In the Hekiganroku , there is a passage that shows vitaworking: We meet strength with weakness, softness, with severity. Dogen clearly saw the need for harnessing this vitality to social action. In GenjoKoan he said: To study Buddhism is to study the self. To study the self is to forget the self. To forget the self is to be enlightened by all things. To he enlightened by all things is to be free from attachment to the body and mind of one's self and others. It means wiping out even attachment to Satori. Wiping out attachment to Satori, we must enter into actual society.

Here is the essence not only of Zen but also of all religions that aim at clarifying the self. It is the process of living by dying-of shedding egoistic delusion and finding our "natural face." This is Satori-the awakening-but we should not stop there. Others must be helped toward Satori: toward an enlightenment that stems not from self-power but from openness to all things. Unbound even by enlightenment, we must participate actively in the ongoing world and work in vital freedom.

In the Kamakura period, Eisai and several other Zen masters brought Rinzai Zen to Japan. This Zen offered spiritual support to the warrior class and helped establish bushido, a warrior code unique to Japan. The warrior's approach to life had much in common with Zen. Both stressed the transcending of life and death; both esteemed courage, resoluteness, simplicity, and austerity. Disciplined action was characteristic of both warriors and Zen priests. Such leaders as Tokimune and Tokiyori were influenced by Zen masters from China.

During the war years at the end of the Kamakura period, the Zen monks were responsible for preserving Japanese education and culture. Among other things the monks taught the common people the Zen influenced Confucianism of Shushi. The bulk of the material published at that time dealt with Zen-often Zen sayings and verses. Zen monks became associated with the ability to read foreign documents.

The Zen monks also developed the Ashikaga School and the terakoya (monastery classes). They set up libraries containing Zen and Confucian works. An example of such a library is the Kanazawa Bunko. Some of these ventures were of considerable size. The Ashikaga School, for example, with Zen priests as principals, once had 3,000 students.

The social welfare efforts of Zen were financed partly by commerce. The Zen monks played a role in trade between Japan and China; the Tenryuji and Shokokuji ships are an example of their enterprise. The profits from this trade went toward rebuilding temples and training priests as well as toward general social welfare.

In the arts Zen infused with architecture, sculpture, painting; calligraphy, gardening, tea ceremony, flower-arrangement, Noh, Yokyoku, Renga, and Haiku. The characteristics of this Zen art have often been discussed. One scholar, for example, finds seven basic characteristics. I believe, though, that four are probably enough-simplicity, profundity, creativity, and vitality. These happen to be characteristics of Zen itself as well as Zen art.

The Zen monks spurned luxury and simplified what they wore and ate. This is evident even today in the Zen monastery life. But this simplicity is far from superficial; it is firmly anchored in depth.

While emphasizing practice, Zen does not ignore philosophy. The philosophic ties are primarily with some of the most profound ideas in Buddhism-with Sunyata of the Prajnaparamita sutra, with mutual interdependence of the Avatamsaka sutra, and with Buddha-nature of the Mahaparinirvana sutra.

Zen was transmitted from mind to mind and from personality to personality. But if master and disciple are merely equal, the spirit of Zen dwindles. If the disciple is the same as the master, the Hekiganroku says, the value of the master decreases by half. The disciple shows his gratitude to the master by transcending him. Herrigel calls this climbing on the shoulders of the teacher.

The essential transmission then may be creativity. The following lines from Keizan are pertinent here:

Zen vitality is full functioning in life based on zazen. Activity rather than passivity characterize Zen. Creativity and vitality are closely related; their rareness in combination constitutes a major modern problem.

How do these four characteristics-simplicity, profundity, creativity, and vitality-show up in Zen art? The best way to find out, of course, is to go to the works themselves. But some indicators may be helpful.

The sumie of Sesshu and the tea ceremony room give the feel of simplicity. Another example is Mokkes painting of persimmons. Profundity animates the Noh plays of Zeami and the Haiku of Basho. The frog-leap-pond Haiku - one of the masterpieces of Basho - may provide an especially good insight into what is meant here. Creativity emerges strongly in the gardens of Muso and the calligraphy of Ryokan. They clearly transcended their masters style. Sesshu also serves as an example here; he learned his technique from Josetsu and Shubun in Japan and Kakei in China, but his final landscapes were incomparably his own. Vitality shimmers through the calligraphy of Hakuin and Ikkyu. Their calligraphy overflows form without violating it. Vitality is also evident in the vigor and free flow of all Zen art.

In Japan such sports as Judo, Kendo, and Karate contain overtones of Zen. They are forms of martial art, emphasizing disciplined behavior, expert-beginner relationship, and intensive training. The training results in tourney actions embodying full functioning and vital freedom.

A Japanese development of Karate is called Shorinji kempo. The followers of this form consider Bodhidharma as the founder. The story has it that one day some bandits attacked the Shorinji to plunder clothing and food. The Zen monks there, having no swords or other weapons, defended themselves with their bare hands. The techniques they used are said to be the basis of present-day Shorinji kempo.

Relaxed activity is effective not only in Judo, Kendo, and Karate, but also in other sports. Athletes in less traditional sports have found merits in Zen discipline. Recently in Japan, a number of baseball players have taken up zazen.

Zen's potential for enhancing effectiveness has also, at another level, drawn the keen interest of scientists. The psychotherapists especially have investigated Zen practices. C. G. Jung's Foreword to D. T. Suzuki's Introduction to Zen Buddhism is one evidence of this interest, and it underlines the similarity between his individuation process and Zen awakening. Karen Homey and Erich Fromm are other well-known figures in psychotherapy whose interest in Zen surpasses the merely curious. Recent studies of Zen training have included electroencephalograms of monks in zazen. The brain waves indicated extreme calm a few minutes after the start of zazen.

In this way, Zen is stirring up wider interest. It is not limited to Japanese art and culture. Scientists both in East and West, if their goal is human wholeness, are looking to Zen for some old but still valid answers.

The Role of Zen in Modern Age

By zen master Prof. Masunaga Reiho

From Zen Beyond Zen by Prof. Masunaga Reiho, Chapter 5, Page 19, 1960.

Modern times can be called the emerging age of humanism. It grew from awareness of humanity and established the autonomy of human beings in contrast to the tyranny of the Middle Ages. Human awareness spurred the development of knowledge from myth to science.

Humanism emphasized individualism and science. For several centuries since the Renaissance these were important factors in creating the modern age.

They helped establish the politics, ethics and social conduct that we know today. They also laid the groundwork for democracy and socialism. Science advanced quickly. It built up knowledge that could not even be imagined in ancient times. In this way modern civilization came into being.

But from here two problems arose. One is the danger of annihilation inherent in modern warfare. The other is the increasing strength of social organization due to the development science. These problems deepened the anxiety of the modern human being. Social and scientific advances seem to have outrun the ability of people who would use them. Some of the users suffer from warped wills; the lack of moral strength. As science progresses human qualities seem to deteriorate. To correct this imbalance we must increase human compassion. Of course, individual good will is important, but in this age it is necessary to stress ethics. From the standpoint of humanity as a whole. We tend to look with amazement at the greatness of science but to remain blind to moral considerations. This is one of the major sources of the anxiety so prevalent today. Essentially this ethical problem is a religious one. From the standpoint of humanity as a whole, we can advance only by breaking through this dead end. The modern crisis stems from the increasing complexity of mechanical and social system.

One way out of this impose, may be Zen. Zen is a practice that penetrates to one's true self through cross-legged sitting and lead to vitalize this self in daily life. Zen frees the human being from the enslavement to machines and enables him to return to his basic humanity. It also eases the mental tension that comes from cultural fatigue and brings peace of mind. Zen maximizes the present moment through full awareness in daily life.

With its emphasis on the idea of Buddha-mind Zen helps the human being to fulfill his potentialities, It can guide Science into less destructive channels. Since it's basic standpoint transcends dualism; Zen offers some hope of softening the ideological conflict that now threatens human existence. The mode of unity has characterized Eastern culture. As Seng-Chao (384-1414) said: Heaven end earth are of the same root. All things are identical with me. The West, on the other hand, has emphasized dualism. From this grew science and philosophy.

Eastern unity, while important to religion, has tended to limit scientific progress, Western dualism, while necessary to science does not leave much room for religions development. The culture of the future must embrace the strong points of both Western scientific thought and Eastern religious intuition. Zen offers some respect of cutting through this apparent conflict and setting the stage for creative use of both science and religion. For Zen has the potentialities for guiding science without departing from the true religious spirit.

This seems to me the role of Zen in the modern world.

Western Interest in Zen

By zen master Prof. Masunaga Reiho

From Zen for Daily Living by Prof. Masunaga Reiho, Page 20, Shunjusha Pablishing Co., 1964.

For man the most important thing is life. Life is always in flux, and it is the creative matrix of the new. Anything without life is dead. Life has creativity and vitality as its essential elements. Originally all living things embody creativity and vitality. But eventually, over many years, they become rigid, form-ridden, and dogmatic. In Decline of the West , Oswald Spengler wrote that the West has civilization but no culture. This weakness has now become apparent in politics, economics and science. Many taboos have emerged in social conventions and traditions. Techniques and machines brought about the industrial revolution; man has been taken up into the cogs of the machinery and has lost his basic humanity. Man, surrounded by machines, mass-communication, and organized systems, has become alienated from freedom and spontaneity. Zen seems unusually well suited to break the deadlock facing modern man. Science has now emerged into the atomic and outer space age. Originally based on humanism, science gradually became to be considered all-powerful and autonomous.

In this way it moved in the wrong direction, luring mankind toward destruction. Zen seems to have a vital role in correcting this false tendency of science. Although the world is said to be moving toward a thaw, the two ideological camps are still in sharp conflict. The weak nations are caught in the middle, wavering from left to right. Zen offers the possibility of basically undercutting this dualism. It can help man overcome the conflict of ideologies for the first time. The West tends to emphasize the individual over the group. But even in individual man there are two facets. They are the false self and the true self.

No matter how much the individual is emphasized, it does no good if the emphasis is on the false self. Through the true-self the dignity of man emerges. In Christianity, God is worshiped as an absolute other he is separated from human beings. Zen, on the other hand, returns the human being to this original wholeness and shows him his true self.

In Buddhism the true self is called Buddha-nature. Buddha-nature includes man's religious nature and true humanity. It is deeply involved in human dignity. Thinkers in Europe and America have sensed this. Zen, with its emphasis on man's true self, has given them new insights into human potentialities. Christianity talks about a future kingdom of heaven and makes it the dwelling place of the soul. But Zen considers this too far removed from the actual world.

Zen tries to help man live fully in this world. This is called the expression of full function. Zen stresses present rather than future, this place rather than heaven. It aims at making actuality the Pure Land. In religion the most important thing is not miracle. Religion, of course, transcends the world of science, but it should not conflict with science. Buddhism is a world religion that envelops science. Any religion that hopes to appeal to modern man must embrace science and as well as transcend it. Zen does this.

In conclusion, Zen

From this grow the Zen characteristics* of simplicity, profundity, creativity, and vitality that have attracted so many Westerners. But unless combined with zazen, Western Zen runs the risk of becoming a form of cultural snobbism.

* S. Hisamatsu in Zen and Art p.24, states that the 7 characteristics of Zen art are asymmetry, simplicity, witherness for (or austerity), naturalness, profundity, detachment, and tranquility. While good, this classification seems to he somewhat ambiguous. It contains some overlapping.

Zen penetrates to man's true self and helps him live it in daily life. In the past few years, Zen has enjoyed something of a boom among intellectuals in Europe and America. This stems partly from Zen's capacity to break the intellectual deadlock induced by mechanical civilization, to correct one-sided dependence on science, and to soften the conflict of ideologies.

In addition, Zen responds to the modern need for simplicity, profundity, creativity, and vitality.

I would like to discuss Western Zen under six classifications - "beat" Zen, conceptual Zen, square Zen, Suzuki Zen, native Zen, and Zen.

Beat Zen

This is the Zen popular among the "beat" in America and the "angry young men" in England. Its proponents rebel against convention and tradition. Seeking freedom, they try to model their actions on those of the monks in Sung China. But most of them lack creativity and moderation. They represent, however, a phase of the process toward deeper understanding.

Conceptual Zen

This is the Zen derived from reading many books. It tries to grasp Zen conceptually and fails because Zen is a practice and not a concept. But the conception can serve as a starting point.

Square Zen

This is the Zen bound by rigid forms and rituals. Its advocates put weight on solving Koans and receiving the certification of the Zen masters. But since Zen stresses vital freedom, there is no need to be so strictly enslaved by form.

Suzuki Zen

This is the Zen that has grown through the works of Prof. Daisetz Suzuki. His contributions to Western understanding of Zen have been tremendous. But his Zen ends to emphasize enlightenment through the Koan. If this emphasis is too strong, Zen loses its original "abrupt" flavor and becomes step-like.

Native Zen

This is the Zen based on native philosophic tradition. It is represented, for example, by the writing of Prof. Van Meter Ames of Cincinnati University. It resembles the kakugi - (matching meanings) method of early China, which adapted Buddhist thought to the native heritage. This method contributed much to the development of Mahayana Buddhism in China. This type of Western Zen has potentiality for contributing significantly to understanding of Zen in Europe and America.

Zen

This is the Zen that grows from right training. Here, the works of Dogen, the founder of the Soto sect in Japan, offer many pointers, especially in his intuition of the self-identity of original enlightenment and thorough practice. This Zen requires a deep philosophic ground, understanding of Zen's historical development, and the guidance of a true Zen master. From these will come an authentic transmission. But of course this transmission should be creative; the disciple should not cling to the teachings of his master but should transcend them. This is the Zen beyond Zen.*

*Dogen criticized the Zen that had become exclusive and intolerant and was tending toward rigid dogma. He pointed to shortcomings in the characteristics associated with Zen in the past, and advocated a Zen beyond Zen.

Much of Zen's appeal today, I believe, stems from this uncompromising view of the whole man. Many Western thinkers are drawn to Zen because it promises fulfillment without the supernatural. Its basic approach could supplement and strengthen such Western ideas as existentialism in Europe and pragmatism in the United States. In an increasingly complex and mechanized world, perhaps there is need for a teaching that helps man toward being himself. Zen seems well suited to restore the sense of life to many who have lost it-to stimulate the creative in man that alone can guarantee his survival.

Among some scholars Zen is regarded as mysticism, and they find this attractive. But can Zen be judged is this way? If Zen is mysticism divorced from reality, how can we live in vital freedom with actual society? In this space age Zen would then also conflict with science. Science forms the basic mood of the present. The wisdom taught by Buddhism does not exclude scientific knowledge but envelops it. A religion conflicting with science is not a religion for the present.

Zen transcends dualism and truly vitalizes the value of science.

No dependence on words and letters does not mean a retreat from knowledge. Rather it indicates no enslavement to words and letters and the bringing out of the true meaning of life. Science, of course, is not omnipotent . It has its own limits. In the spiritual background of Zen there is the wisdom of Sunyata . Sunyata wisdom does not depend on anything, does not become enslaved to anything, and does not cling to delusion. It denies a rigid view of substance. To consider Zen as mysticism and to be fascinated by this is to rob Zen of life.

Zen and Judo

By zen master Prof. Masunaga Reiho

From Zen for Daily Living by Prof. Masunaga Reiho, Page 25, Shunjusha Pablishing Co., 1964.

Growing interest in Zen and Judo has gone along with the so-called Japan boom in the West. While superficially quite different, Zen and Judo are essentially similar. Judo is the art of using one's strength, both physical and mental, with maximum effectiveness. Through practice in offensive and defensive tactics, it helps the trainee realize the full potentialities of his body and mind. The successful trainee gains an insight into his true self and emerges with a desire to work for social good. To reach this stage is the ultimate goal of Judo.

This goal jibes with the two ideals of Kodokan Judo to make the most effective use of one's energy and to contribute to the mutual growth of oneself and others. These ideals focus the trainee's effort toward helping others to achieve the same joy-bringing growth. Kodokan Judo differs from the Jujutsu of ancient Japan. Traditional Jujutsu featured many tricks whose purpose was to maim opponent. It was also something of a show put on for paying customers. Jigoro Kano, the founder of Kodokan Judo, changed all this. After studying various ancient Jujutsu schools, he picked out the best techniques and systematized them. Kano did not limit his aim merely to a contest to determine victory or defeat. He made body-mind training an integral part of his system.

Though derived from the Jikishin School, the word "Judo" takes in more than the technical. Kodokan Judo, of course, teaches technique, but its main emphasis falls on "do" - the way to self-realization.

It aims primarily at experiencing the "way." In the process the Judoka enjoys a sport and sharpens his ability for self-defense.

In 1890, Kano was sailing back to Japan from Europe. While crossing the Indian Ocean, he was, through a misunderstanding, challenged to a fight by a huge Russian on board. As the fight began, the Russian tried to grab Kano in a bear hug. Kano, seeing an opening, twisted around and threw his opponent with Ogoshi (one of the Judo hip throws).

The Russian arched overhead, seemingly toward a headfirst landing on the deck. But Kana kept a firm grip on his opponent's wrist and brought him down on his feet. The spectators were impressed not only by the well-timed throw but also by the cushioning of the fall. The Russian shook Kano's hand. They parted good friend. This episode underscores the Judo ideals of strength fully used and of mutual growth.

Learning in Judo begins with ukemi - the art of falling. By practicing ukemi the trainee learns to fall safely no matter how he may be thrown. At the same time, he builds up his own confidence and deepens his interest in Judo.

Next, the trainee learns the art of throwing. He develops an under- standing of how to use his strength most effectively. By constant practice he begins to master the various ways to break his opponent's balance and make a throw. A throw, it is said, must be practiced 3,000 times before it can become effective.

Judo mat-work, although not too popular these days, must also be practiced. It is just as important to the mastery of Judo as the art of throwing. The two go together like the two wheels of a cart.

In working out with an opponent, the Judo trainee should move relaxed and tryout his newly learned techniques without hesitation. He must act positively: when thrown, he should break his fall, arise immediately, and resume the attack. To test his strength, the trainee should occasionally take part in Judo tournaments.

Quite often, a new set of attitudes develops as a result of this training.

The trainee may find himself:

Judo training, in short, stimulates courage and freedom of action, teaches constant awareness and resourcefulness, and helps develop respect for human dignity and tempers body and mind for vital social action. With flexibility and grace, or in the words of an ancient text, like a shadow following an object, the Judoka quietly does his part of the world's work.

In Tokugawa Japan, master swordsmen like Yagyi Tajima-no-Kami and Miyamoto Musashi studied Zen to learn the innermost secret of swordsmanship. They often took up Zen training under famous masters. Some, after the usual round of sharp criticism and psycho-physical discipline, managed to gain enlightenment. A similar relationship holds for Judo and Zen.

Gaining of full Zen enlightenment does not differ from experiencing the ultimate meaning in Judo. In this way, both Zen and Judo trainee come upon the truth of life. Through intensive training they experience what it is to know coolness and warmth for oneself. As Dogen has said, Training enfolds enlightenment. Enlightenment dwells within training, and training takes place within enlightenment.

One cannot know anything deeply or experience it completely with out undergoing some hardship. While Zen has been called the comfortable entrance , it is actually not so easy. The trainee usually gets up early in the morning to practice zazen (cross-legged sitting). During sesshin (the special training period), he does zazen for seven days. Cold and sleepiness disturb him, and his feet and legs begin to hurt. Usual monastery routine demands that the trainees sweep the garden in the morning and do zazen again in the evening.

Similarly, Judo has its special training period-kangeiko (winter practice) and doyogeiko (summer practice). Having gone through both kangeiko and Zen training, I can vouch for the fact that neither is easy. But only through disciplined practice without regard for heat and cold the trainee can gain an inkling of what a total experience means in Zen or Judo. You don't learn swimming by practicing on the tatami .

Both Zen and Judo grow out of the self-identity of body and mind. To train the body and mind in Zen the emphasis falls on letting go in the truly existential sense . Dogen, it is said, transmitted the relaxed mind from China "Relaxed" of course does not mean "soft". It means breaking free from the tyranny of the ego and penetrating to the not self or the Self. Freed even from the desire for enlightenment, one understands finally what makes the world tick.

In Judo, too, the body and mind are relaxed. There is no burning desire to win. The Zen insight into the non-duality of body and mind dwells at the center of Judo. A Zen-calmed mind expresses itself in integrated action. Full function of body-mind leaves no opening.

A lion, it is said, uses his full effort to catch a rabbit. The same is applied to Judo. One throws, holds, and wrestles going all out, but without strain. The body shifts immediately to adjust to changes in time and place. Those with Judo sense escape injury in usually dangerous falls. They can take care of themselves with ease against violence.

So Judo goes beyond mere self-defense. It builds up character and leads to responsible freedom. Harmonizing with nature, Judo stresses effortless action. Similarly, Zen respects the natural order of things. One's every day mind is itself the way is a well-known Zen expression.

Just as the bird in the sky and the fish in the water leave no traces of their passing, Judo leaves no aftermath. The breaks are clean. In Judo as in Zen, when awareness is full, every action embodies vital freedom. The great masters of Zen and Judo move along the same path of no-hindrance.

The Zen trainee understands "no-hindrance" primarily through zazen in upright sitting and rhythmic breathing. This training method strikes most Westerners as rather strange. But it corresponds to the throws practiced 3,000 times in Judo. Both Zen and Judo, therefore, put their basic emphasis on ultimate freedom and creativity. The Zen trainee not only must absorb all that the master has to teach but also must excel him. The trainee has to transcend his teacher. This, as Prof. Eugene Herrigel has said in his Zen and the Art of Archery , means, to climb on the shoulders of one's teacher. Judo also has many creative aspects, least subtly perhaps in the development of new techniques. It too uses form to wean man away from enslavement to form.

When fully experienced, Zen and Judo help replace illusion with insight. They give us a fresh approach to the terms of the world. Previously routine activities then take life, and we find the buried wisdom in what seems at first glance to be the least rewarding of Zen sayings, Every day is a good day: every hour is good hour.

The spirit of Zen is not only important for Judo but for all sports. Zen puts stress on living fully in the moment, and this mood is necessary to all sports. Both Zen and sports also emphasize training (the so-called sport samadhi ), observance of rules, learning from masters, and objective excellence. Other similarities include their common stress on attention to details, grace of movement, and growing by participation. While perhaps less evident in some sports than in Zen, is not the ultimate aim of both freedom from obsession to defeat and victory? The Zen of sport and the sport of Zen can both lead to more meaningful living.

The Standpoint of Dogen and His Ideas on Time

By zen master Prof. Masunaga Reiho

From Soto Approach to Zen by Prof. Masunaga Reiho, Chapter 4, Layman Buddhist Society Press, 1958. pp. 59-80.

Religion tries to penetrate to the true ground of the contradictory self by transcending the ego-bound self and experiencing the real self. By focusing on death and sin, it strengthens our sense of the absolute, expands our sense of life, and purifies the sense of the sacred in our body and mind. Among religions Zen is an immanent transcendent type that makes zazen (cross-legged sitting) the basic form of practice that approaches the origin of the mind, and that directly experiences the absolute.

Dogen, in the GenjoKoan fascicle of his masterwork Shobogenzo (The Eye and Treasury of the True Law), makes this statement: To study Buddhism is to study the self. To study the self is to forget the self. To forget the self is to be enlightened by all things. To be enlightened by all things is to be free from attachment to the body and mind of one's self and of others. This implies wiping out even one's attachment to satori . Detaching ourselves from Satori, we must enter the day-to-day world. This sums up the essential character of religion. If we question the experience of the self, we become confused about where the self should be. If we become anxious about the experience of the self, we start knocking at the door of religion. Penetrating to the deepest true of the self, religion tries to transcend the ego and release the true self. But we have to seek the self by denying the self. Conduct based on self-desire and self-attachment is evil. In every religion the emphasis falls on denying the self. When we deepen our faith, we touch non-ego-a state free from the ego's dualistic thinking. Buddhism, setting up the principle that all things have no ego-substance, especially stresses the realization of no- ego. But the more deeply man reflects on the status of the self, the more he has to seek the absolute ground beyond the self. Belief springs not only from man's subjective demand, but also from his response to the beckoning of the absolute. It comes from the absolute and depends on the call of God. But this God is not only the object but also the ground of the object; He is not only the subject but also the ground of the subject. In Shoji, Dogen says:

When you let go of your mind and body and for get them completely, when you throw yourself into Buddha's abode, when everything is done by the Buddha, when you follow the Buddha Mind without effort or anxiety-you break free from life's suffering and become the Buddha.

When we transcend the subject and touch its ground, we come in contact with the absolute. The mind of God appears in the flowers in the field and the birds in the air. In them we see the form of the absolute. The truth speaks through objects. Arising from the Buddha, it takes shape in the world.

Thus one's body-mind and the body-mind of others are essentially free from conflict. The gap between one's self and others naturally falls away and invites unity. So attaining enlightenment does not call for pride. The enlightened returns to the day-to-day world, takes part in historical reality, and vitalizes Buddhism. Asanga called this Apratisthita-nirvana (enlightenment of no abode). In Zen Buddhism we call it training after enlightenment.

The severe and thorough style of Dogen's Zen was no doubt influenced by his master, Ch'ang-weng Ju-tsing (1163-1228). We can find two facets in Dogen - the carrying on of tradition and the realizing of individual potentiality; if we examine his career and his many books, especially the Shobogenzo.

Dogen wanted to return to the fundamental spirit of the Buddha from a critical standpoint. He spanned court life and tried to train a small group of elite followers. He rejected the idea that the three training - Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism could be reconciled. He criticized the rivalry among the five schools of Zen and tried to live in the oneness of Buddhism. He even refused to use the name Zen "sect." In short, he dwelt, like his teacher Ju-tsing, in supreme meditation - free from attachment to body and mind. Dogen's personal approach can be summarized as follows:

The idea of impermanent Buddhahood necessarily introduces us to the problem of time. In the history of Buddhist thought there have been many essays on time - like the Madhyamika and Fa-tsang's (643-712) Hua-yen-t'an-hsuan-chi.

But Dogen seems to have gone further than most in organizing time-experience as a system of thought. In Shobogenzo the problem comes up in such essays as Uji, Kenbutsu, Sansuikyo, Daigo, GenjoKoan, Kuge, Kaiinzammai, Menju, Bussho, and Zenki.

An especially detailed study of time is contained in Uji. The date at the end of this essay indicates that it was written in the early winter of 1240 at the Kosho Horin temple in the suburbs of Kyoto. At that time Dogen was 41 years old. Making Uji the focus and referring to other writings of Dogen, let us treat his thoughts on time in terms:

As St. Augustine said: If no one asks me about time, I know all about it; but if someone asks, I know nothing about it. It is difficult to explain time when it is so closely linked up with our lives and flowing in the same current. Generally time tends toward abstraction. But in Dogen, time is practical-a means of grasping reality. Time - like space - has been considered a form of cognition. The idea has been that objects must exist in a fixed place and time before they can result in sensation and intuitional knowledge. Time and space, therefore, are prerequisites to direct knowledge in traditional Western thought. They

However:

The word "Uji" refers to a specific time taken from infinite continuity. It points to the existence of a discontinuous time expressed as "this time" and "that time." At the beginning of the Uji essay, Yueh-shan is quoted as saying: Standing on the peak of a high mountain is Uji. Diving to the bottom of the deep ocean is Uji. You and your neighbor are Uji. The great earth and vast sky are Uji. All these instances are limited to an independent and isolation special time.

But Dogen himself refers to time cut off from past and future as ordinary time and contrasts it with basic time. This special time can be compared to Heidegger's "vulgare Zeit" of ordinary life (Alltagichkeit). Time flows but it is not simple flowing. Uji contains elements that are difficult to express simply in terms of individualized special time. To take Uji only as a single time unit and see it as part of the time flow does not go beyond the common understanding of specific time. About this, Dogen says: If you think of uji in the common way, even wisdom and enlightenment become only appearances in time coming and going. Time is flowing without flowing, and it takes shape in the flow without flow.

From one point of view, time is isolated in each moment and disconnected from past and future. From another point of view, it manifests new time each moment and connects up the past and future. Dogen says in GenjoKoan . You must understand that a burning log-as a burning log-has before and after. But although it has past and future, it is cut off from past and future. The statement that the log has before and after refers to the continuity of time. Cut off from past and future refers to the discontinuity of time.

But no matter how long time continues, there is only the moment. Dogen expresses this thought in these words: It continues from today to day. Time goes from the present to the present. And discrete continuity and unmoving motive are only possible in this moment. This is the now of specific time-the eternal present. Commenting on this problem, Tenkei Denson (1648-1735) says: Mount is time; eternity is time. Time is no time-is eternity. The idea of time as no time refers to absolute timelessness. This is the absolute present. Shuho Myocho (1282-1336) says: We have been separated for so long and have never been apart. We meet each other throughout the day, and do not meet a moment. The present embraces the past and future: it is absolute. The conflict between continuity and discontinuity is resolved here. This is called the unity of specific time and continuity.

In Daigo, Dogen writes: The so-called present is every man's now. When now we think a past and future, myriad times are the present. They are the now. The original nature of man is the present. This recalls St. Augustine, who argued that instead of setting up the three times categories of past, present, and future, we should say present of the past, present of the present, and present of the future. Dogen says: Time seems to be beyond but it is now. Time seems to be over there, but it is now. The now of specific time continues, embracing the past and future. The moment is eternity.

We first realize the meaning of "now" by training. In Gyoji , Dogen says: Before practice there is a way called 'now.' Realizing practice is called now. There is no real present apart from human action. Where we truly live, we find the present-and nowhere else. Outside the now of practice there is no essential self.

In the Gyoji essays, Dogen also writes: The great way of the Buddha and the patriarchs always has supreme practice; it circulates and is never cut off. Through this practice, which always circulates and is never cut off, the essential self emerges. Man must live the life of now - and die the death of now. Purifying his activities, he must live fully in life; in death, he must eliminate complications and die with thoroughness.

For those who are not pushed around by the hours of the day - for those who make active use of them - every day is a good day, and every hour is a good hour. Those people can then be a vital factor everywhere and make truth live wherever they stand.

In the first part of Zuimonki , Dogen says: Without looking forward to tomorrow every moment, you must think only of this day and this hour. Because tomorrow is unfixed and difficult to know, you must think of following the Buddhist way while you live today. He makes a similar statement in the second part of the essay: You must concentrate on Zen practice without wasting time, thinking that there is only this day and this hour. After that it becomes truly easy. You must forget about the good or bad of your nature, the strength or weakness of your power. The essence of religion in Dogen's mind, lies in living truly in the now of specific time. Realizing the value of life depends on expressing the day and months of a hundred years in each day's living. By unimpeded practice that cuts off past and future, we fulfil the meaning of life for the first time. Thus this day should be vital, Dogen says in Gyoji . To live one hundred years wastefully is to regret each day and month. Your body becomes filled with sorrow. Although you wander as the servant of the senses during the days and months of a hundred years - if you truly live one day, you not only live a life of a hundred years, but save the hundred years of your future life. The life of this one-day is the vital life. Your body becomes significant. True religious life thus comes into being through the now realized in practice.

Let us now consider Dogen's view of life-death in relation to the problem of time. To be concerned with life-death is the very essence of religion. Originally man could touch the abode of his self at the moment of death. Death is inherent in the self; it does not belong to others but is connected with one's self. It is difficult to overlook. It is the most obvious of facts. We worry, wondering when it will come to us. This self is the only one, and this life comes but once. The deads do not return. All living things die - man is truly mortal. Those who, like animals, live unaware of life's impending dissolution find it difficult to grasp the true self.

The fear of death means attachment to life. But arising, decaying, and changing are the true aspects of life and the essential characteristics of human existence. If birth and death are put in opposition, birth precedes death, and death follows birth. This viewpoint aggravates the difficulty of penetrating the problem of life-death. In Shinjingakudo , Dogen says: Although we have not yet left birth, we already see death. Although we have not yet left death, we already see birth. This runs counter to the common view of birth-death. Birth and death are the two sides of human existence. Every moment is birth from one standpoint and death from another. Each moment we live and die. Life is a moment of growth and a moment of decay. Death pervades life, and life pervades death. And it is birth and death that give significance to human existence. From the usual viewpoint birth and death are nothing but transmigration. Those enslaved by the idea of an ego cannot break free from the stream of birth and death; they have lost their freedom of escape. If ego-attachment is severed, we realize that the continuity of birth and death is itself the expression of Buddhahood and thus gain control over birth and death. Be cause the Great sage gained insight into life and decay, he did not fear birth and death; instead be made life-and-death existence a place for training. Therefore, Dogen says: Although birth and death are the transmigration of the unenlightened, the Buddha is free from all this. For those who have control over them, birth and death are not things to be feared and avoided. They are transmitted instead to the coming and going of light. In Bendowa , Dogen says: To think that birth and death are things to be avoided is a sin against Buddhism. They are truly the tools of Buddhism.

It is said that time is cut off from past and future although it has past and future. In this way, birth and death, while continuing without pause, are absolute existences disconnected from one moment to the next. Birth is one position of time, and death, too, is one position of time. But the now of specific time that connects birth and death is an absolute, unchallengeable reality Apart from this moment there is no birth and death anywhere. Outside the present, we seek life; outside the present, we are terrified by death-this is the common delusion. We must live the life of now to the fullest; we must die the death of now without hesitation, Here abides the full realization of all functions. About this, Yuan-wu K'o-ch'in (? -1135) says: Life is the realization of all functions; death is the realization of all functions. Buddhahood is expressed in full, whether in life or death.

We must regulate life and death, while living and dying our life and death. Because life and death and coming and going are true human actions, to throw them away in denial is forsaking the life of the Buddha. Therefore, says Dogen in Shoji : If life comes, there is life. If death comes, this is death. There is no reason for your being under their control. Don't put any hope in them. This life and death are the life of the Buddha. If you try to throw them away in denial, you lose the life of the Buddha. Chia-shan says: If the Buddha is within life and death, we are not confused by life and death. Ting-shan says: If there is no Buddha within life and death, it is not life and death. Both are trying to explain the problem of life and death, but Chia-shan view life-death and the Buddha dualistically. Ta-mei Fa-ch'ang (752-839) had to criticize him: He is far from the Way. Dogen says: If a man seeks the Buddha without life and death, it is like turning the cart to the north and heading for Esshu (Yueh-chou), or looking south to see the North Star. We will gather the cause of life and death more and more-and lose the way to liberation. We can transcend life-death if we study and do what we must in the present moment without pursuing the past or waiting for the future. A relevant passage appears in the sutra (M.N.): Don't pursue the past: don't wait for the future. .... Just do today with all your heart what must be done today. Who can know the death of tomorrow?

Dogen's view of life and death is closely connected with applied time. In Kenbutsu , Dogen says: Though we say the Buddha of the past, present, and future, this differs from the common time standard. The so-called past is the top of the heart; the present is the top of the fist; and the future is the back of the brain. Regarding this, the "Benchu," a commentary by Tenkei on the Shobogenzo, says The three worlds of past, present, and future are your heart fist and brain. They are not the three times of common sense. They are the abode of your own body in the 10 worlds of past and present. Although called the three worlds of past, present, and future, there is nothing but this moment as the self-fixation of the eternal now.

Thus Dogen, while inheriting the tradition, realized his own individuality. In the world of philosophy and religion he opened up his own vista. In Japan he greatly influenced the generation that followed. His ideas or time compare favorably with modern Western philosophy. In fact, they may open up new avenues to an East West cultural synthesis.

Fukanzazengi (Rules for Zazen)

Written by zen master Dogen Zenji translated by Prof. Masunaga Reiho

Translated in Soto Approach to Zen by Prof. Masunaga Reiho, Chapter 7, Layman Buddhist Society Press, 1958. pp. 100-105.

Dogen wrote this essay in the latter half of 1227 (between October 5 and December 10). He was then 28 years old and had just returned from China. His object was to popularize the Buddhism of zazen, to teach the right method of zazen, to transmit the Zen style of Bodhidharma, and to make known the true spirit of Pai-ch'ang.

Dogen has described the motive for this work in zazengi Senjitsuyuraisho (Reason for writing the Rules of Zazen). Dogen modified the rules of zazen in the eighth volumes of Zennenshingi (Ch'an-yuan-ch'ing-kuei) written by Tsung-che (Shusaku) in 1102. Dogen' work, therefore, contains the characteristic method of truly transmitted zazen, and it is supplemented with complete notes. This work remains in two forms: a "popular" edition and one written in Dogen own hand. The "popular" edition appears in the Eiheigenzenjigoroku (published in 1358) and the eighth volumes of Eiheikoroku (published in 1472). But they differ considerably from the edition in Dogen own handwriting. Kept in the Eiheiji repository. This edition reproduces in that the Zazengi written in 1227. Dogen, however, polished the "popular" edition, in the final 20 some years of his life, and he arranged it in the Chinese style that we now see. This translation is based on the "popular" edition.

The true way is universal so why is training and enlightenment differentiated? The supreme teaching is free so why study the means to it? Even truth as a whole is clearly apart from to dust. Why adhere to the means of "wiping away"? The truth is not apart from here, so the means of training are useless. But if there is even the slightest gap between, the separation is as heaven and earth. If the opposites arise, you lose the Buddha Mind. Even though you are proud of your understanding and have enough enlightenment, even though you gain some wisdom and supernatural power and find the way all illuminate your mind, even though you have power to touch the heavens, and even though you enter into the area of enlightenment - you have almost lost the living way to salvation. Look at the Buddha: though born with great wisdom, he had to sit for six years. Look at Bodhidharma, who transmitted the Buddha Mind: we can still hear the echoes of his nine-year wall gazing. The old sages were very diligent. There is no reason why modern man cannot understand. Just quit following words and letters. Just withdraw and reflect on yourself. If you can cast off body and mind naturally, the Buddha Mind emerges. If you wish to gain quickly, you must start quickly.

In meditating you should have a quiet room. Eat and drink in moderation. Forsake myriad relations-abstain from everything. Do not think of good and evil. Do not think of right and wrong. Stop the function of mind, of will, of conscious ness. Keep from meaning [Errata Note: meaning = measuring] memory, perception, and insight. Do not strive to become the Buddha. Do not cling to sitting or lying down.

In the sitting place, spread a thick square cushion and on top of it put a round cushion. Some meditate in Paryanka (full cross-legged sitting) and others in half Paryanka. Prepare by wearing your robe and belt loosely. Then rest your right hand on your left foot, your left hand in your right palm. Press your thumbs together.

Sit upright. Do not lean to the left or right, forward or backward. Place your ears in the same plane as your shoulders, your nose in line with your navel. Keep your tongue against the palate and close your lips and teeth firmly. Keep your eyes open. Inhale quietly. Settle your body comfortably. Exhale sharply. Move your body to the left and right. Then sit cross-legged steadily.

Think the unthinkable. How do you think the unthinkable? Think beyond thinking and unthinking. This is the important aspect of sitting.

This cross-legged sitting is not step by step meditation. It is merely comfortable teaching. It is the training and enlightenment of thorough wisdom. The Koan will appear in daily life. You are completely free - like the dragon that has water or the tiger that depends on the mountain. You must realize that the Right Law naturally appears, and your mind will be free from sinking and distraction. When you stand from zazen, shake your body and arise calmly. Do not move violently. That which transcends the commoner and the sage - dying while sitting and standing is obtained through the help of this power: this I have seen. Also the supreme function (lifting the finger, using the needle, hitting the wooden gong) and enlightenment signs (raising the hossu, striking with the fist; hitting with the staff; shouting): are not understood- by discrimination. You cannot understand training and enlightenment well by supernatural power. It is a condition (sitting, standing, sleeping) beyond voice and visible things. It is the true beyond discriminatory views. So don't argue about the wise and foolish. If you can only train hard, this is true enlightenment. Training and enlightenment are by nature undefiled. Living by Zen is not separated from daily life.

Buddhas in this world and in that, and the patriarchs in India and China equally preserved the Buddha seal and spread the true style of Zen. All actions and things are penetrated with pure zazen. The means of training are various, but do pure zazen. Don't travel futilely to other dusty lands, forsaking your own sitting place. If you mistake the first step, you will stumble immediately. You have already obtained the vital functions of man's body. Don't waste time in vain. You can hold the essence of Buddhism. Is it good to enjoy the fleeting world? The body is transient like dew on the grass-life is swift like a flash of lightning. The body passes quickly, and life is gone in a moment.

Earnest trainees, do not be amazed by the true dragon. And do not spend so much time rubbing only a part of the elephant. Press on in the way that points directly to the Mind. Respect those who have reached the ultimate point. Join your-self to the wisdom of the Buddhas and transmit the meditation of the patriarchs. If you do this for some time, you will be thus. Then the, treasure house will open naturally, and you will enjoy it to the full.

Genjo Koan

Written by zen master Dogen Zenji translated by Prof. Masunaga Reiho

Translated in Soto Approach to Zen by Prof. Masunaga Reiho, Chapter 9, Layman Buddhist Society Press, 1958. pp. 125-132.

The Shobogenzo flow consists of ninety-five chapters. But when first put together it had only seventy-five chapters. Dogen revised these seventy-five chapters between 1248 and 1252. He finished this revision one-year before his death.

The first chapter in this collection is the GenjoKoan It was written when Dogen was 34 years old (mid-autumn 1233) and given to Mitsuhide Yo, a layman in Kyushu.

In the Zen sect Koan means problem to be solved. The Zen master gives it to the trainee, and the trainee thinks about it during zazen. The Rinzai sect especially emphasizes the Koan, but the Soto sect does not put too much stress on it. The Soto sect lays stress on daily life; it believes that the Koan should be expressed in our daily activities.

GenjoKoan deals with the Koan expressed in daily life. First, Dogen here indicates the essence of religion from his standpoint. Secondly, he expresses his basic view that original enlightenment and superior training are self-identical. Thirdly, he makes it clear that the Koan is not a formal problem but a way of life. Here he expresses the Soto view that thorough training should be integrated with zazen and daily life. GenjoKoan especially underlines these points. Though given to a layman, this essay is very difficult to understand. Anyone who understand it will be able to grasp the overall spirit of the Shobogenzo and the essence of Dogen' Zen.

When all things are Buddhism, delusion and enlightenment exist, training exists, life and death exist, Buddhas exist, all-beings exist. When all things belong to the not-self, there are delusion, no enlightenment, no all beings, no birth and decay. Because the Buddha's way transcends the relative and absolute, birth and decay exist, no delusion and enlightenment exist, all-beings and Buddhas exist. And despite this, flowers fall while we treasure their bloom; weeds flourish while we wish them dead. To train and enlighten all things from the self: is delusion; to train and enlighten- the self from all things is enlightenment. Those who enlighten their delusion are Buddhas; those deluded in enlightenment are all-beings. Again there are those who are enlightened: on enlightenment-and those deluded within delusion. When Buddhas are really Buddhas, we need not know our identity with the Buddhas. But we are enlightened Buddhas-and express the Buddha in daily life. When we see objects and hear voices with all our body and mind-and grasp them intimately-it is not a phenomenon like a mirror reflecting form or like a moon reflected on water. When we understand one side, the other side remains in darkness. To study Buddhism is to study the self. To study the self is to forget the self. To forget the self is to be enlightened by all things. To be enlightened by all things is to be free from attachment to the body and mind of one's self and of others. It means wiping out even attachment to satori . Wiping out attachment to Satori, we must enter actual society. When man first recognizes the true law, he unequivocally frees himself from the border of truth. He who awakens the true law in him self immediately becomes the original man. If in riding a boat you look toward the shore, you erroneously think that the shore is moving. But upon looking carefully at the ship, you see that it is the ship that is actually moving. Similarly, seeing all things through a misconception of your body and mind gives rise to the mistake that this mind and substance are eternal. If you live truly and return to the source, it is clear that all things have no substance. Burning logs become ashes - and cannot return again to logs. There for you should not view ashes as after and logs as before. You must understand that a burning log - as a burning log - has before and after. But although it has past and future, it is cut off from past and future. Ashes as ashes have after and before. Just as ashes do not become logs again after becoming ashes, man does not live again after death. So not to say that life becomes death is a natural standpoint of Buddhism. So this is called no-life.

To say that death does not become life is the fixed sermon of the Buddha. So this is called no-death. Life is a position of time, and death is a position of time . . . just like winter and spring. You must not believe that winter becomes spring - nor can you say that spring becomes summer. When a man gains enlightenment, it is like the moon reflecting on water: the moon does not be-come wet, nor is the water ruffled. Even though the moon gives immense and far-reaching light, it is reflected in a puddle of water. The full moon and the entire sky are reflected in a dewdrop on the grass. Just as enlightenment does not hinder man, the moon does not hinder the water.

Just as man does not obstruct enlightenment, the dewdrop does not - obstruct the moon in the sky. The deeper the moonlight reflected in the water, the higher the moon itself. You must realize that how short or long a time the moon is reflected in the water testifies to how small or large the water is, and how narrow or full the moon.