ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

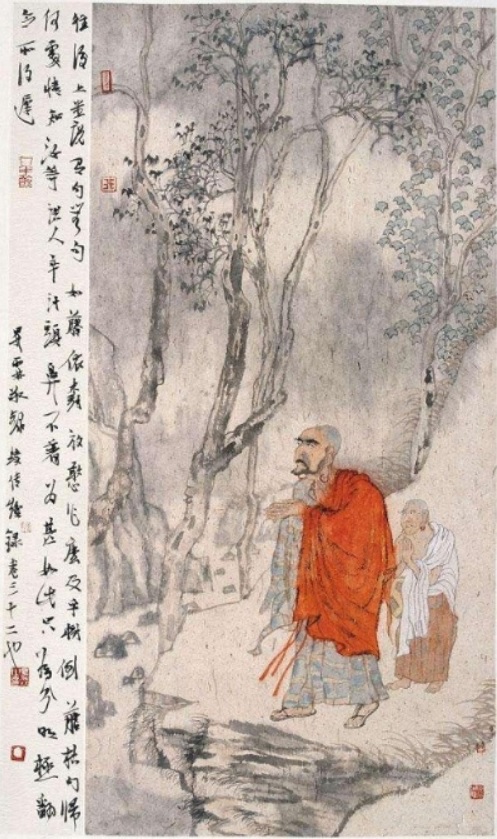

漸源仲興 Jianyuan Zhongxing (b. ca. 800?)

(Rōmaji:) Zengen Chūkō

Suggestions for Zen Students by Zen-Getsu*

*[漸源仲興 Jianyuan Zhongxing (Zengen Chūkō) d.u.]

In: Senzaki, Nyogen and McCandless, Ruth. Buddhism and Zen. New York: Philosophical Library, 1953, pp. 84-85.

The biography of Zengetsu is unknown except that he was a student of 德山宣鑑 Deshan Xuanjian (Tokusan Senkan, 782-865) and Shishuang Qingzhu 石霜慶諸 (Sekiso Keisho, 807–888).

Shishuang Qingzhu or Qingju 石霜慶諸 (Shih-shuang Ch'ing-chu, Sekiso Keisho), 807-888. Not to be confused with Ciming (Shishuang) Quyuan. A Dharma-heir of Daowu Yuanzhi, in the line of Yaoshan Weiyan. He practiced as rice steward under Guishan before studying with Daowu. Dongshan Liangjie had a monk track him down and he was appointed abbot on Mount Shishuang. His community there was noted for never laying down to sleep and was called the "Dead Tree Hall." He appears in Records of Serenity 68, 89, 96, 98. He appears in the Sayings and Doings of Dongshan (Dongshan yulu) section 75. See Dogen's Gyoji.

Living in the world, yet not clinging to or forming attachments for the dust of the world, is the way of a true Zen student.

Witnessing the good actions of another person, encourage yourself to follow his example. Hearing of the mistaken action of another person, advise yourself not to emulate it.

Even though you are alone in a dark room conduct yourself as though you were facing a noble guest.

Express your feelings, but never become more expressive than your true nature.

Poverty is your treasure. Do not exchange it for an easy life.

A person may look like a fool and yet not be stupid. He may be conserving his wisdom and guarding it carefully.

The virtues are the fruits of self-discipline, and do not drop from heaven of themselves like rain or hail.

Modesty is the foundation of all virtues. Let your neighbors find you before you make yourself known to them.

A noble heart never forces itself forward. Its words are as rare gems seldom displayed.

Every day is a fortunate day for a true student. Time passes but he never lags behind.

Neither glory nor shame can move his heart.

Do not discuss right or wrong. Always censure yourself, never another.

Some things, although right, were considered wrong for many generations. Since the value of righteousness may be recognized after centuries, there is no need to crave immediate appreciation.

Why do you not leave everything to the great law of the universe and pass each day with a peaceful smile?

A Sermon Delivered for Nun Eshin 比丘尼恵信

In: Dōgen and the Feminine Presence: Taking a Fresh Look into His Sermons and Other Writings

by Michiko Yusa

Religions 2018, 9(8), 232;

https://www.mdpi.com/2077-1444/9/8/232/htm#fn056-religions-09-00232

The next is a sermon Dōgen gave in response to the request made by Nun Eshin to commemorate the anniversary of the death of her father. Nun Eshin had most likely been a member of the practitioners affiliated with the disbanded Nihon Daruma Sect, before she joined Dōgen’s sangha together with her co-practitioners in around 1240.53 This sermon by Dōgen is dated from the spring of 1246. On June 15 of that year, he renamed the temple Daibutsuji as Eiheiji, making this as one of the last sermons he delivered at Daibutsuji:

Once you understand one principle, you understand all principles. Once you know heaven, earth, and man, you know all the Buddhas. Therefore it is said: ‘To have the sense of gratitude (on 恩) for one’s parents is to return their love.’

When a monk Zengen Chūkō (漸源仲興, Jianyuan Zhongxing, d.u.) accompanied his master Dōgo Enchi (道吾円智, Daowu Yuanzhi, 769–835) and went to a house to make a condolence call, Zengen, touching his hand on the coffin, asked the master: “Alive or dead?” Dōgo responded: “Neither alive nor dead.” Zengen further pressed on: “Why is it that you don’t say alive or dead?” Dōgo only said: “I won’t say, I won’t say.”54

Commented on this kōan, Dōgen said: to talk about whether one is alive or dead only shows that the questioner is ignorant of the Buddhas of the past, present, and future. About the reality of being alive or dead, animals know it better. “To say neither alive nor dead” paints a picture of an old steel-like ox laying down its belly on the sand because of its age. “Why don’t you speak?” means the tip of the tongue is long, while the width of the mouth is narrow. “I won’t say, I won’t say” is the experience of a tiger, the king of the beasts, when it had its first cub.55

53Tajima (1955), pp. 167–68. Tajima conjectures that her dharma name shares in common the sinographs “e”—慧 or 恵—which was given to a group of practitioners who formed a sub-sect within the former Nihon Daruma Sect. For instance, Etatsu 慧達, who took the tonsure and became a monk under Dōgen, was a member of this group; in celebration of this occasion Dōgen composed his hōgo, “Hokke ten hokke” [“The lotus flower turning upon itself”] (1241) and gave it to Etatsu; SG 4.429–49.

54

Zengen Chūkō (d.u.) was a dharma heir of Dōgo Enchi (d.u.). The reality of being alive or being dead is not something one can talk about “objectively,” but it belongs to the realm of experience and feeling. Thus, the master kept his mouth shut on this point, while the disciple wanted a yes-no answer.

55

Dōgen, Eihei kōroku, Sermon #161, DZZ 3.104–5. The kōan based on which Dōgen gave his sermon is compiled in The Blue Cliff Record, Case 55.

I won't say alive, and I won't say dead

http://www.seanewsonline.com/seanews/misc/180215e.htm

On one day during the Tang Dynasty of China (618-907), Zen-master DaoWu YuanZhi (道吾円智: 769-835) went to one of his temple-followers' house to express condolences together with one of his disciples called JianYuan ZhongXing (漸源仲興) who was in charge of Dianzuo (典座), one of the six administrators of a Zen temple in charge of food and other matters. Like Dianzuo that JianYuan was, he apparently couldn't be dealt with easily.

Sure enough, when they arrived at the house, JianYuan tapped on the coffin and asked DaoWu, "Alive or dead?"

DaoWu said, "I won't say alive, and I won't say dead."

"Why won't you?" JianYuan demanded.

DaoWu said, "I won't say, I won't say."

Even as many people were weeping and mourning for the dead, DaoWu and JianYuan neglected the funeral and were bandying words in front of the coffin. Such behavior seems to be quite strange even though they were Zen monks. However, a funeral is an event of a milestone in one's life which everyone must definitely pass through. Thus the master and the disciple might have collaborated and played a typical Zen Buddhist style gospel skit in that occasion.

However, on the way back JianYuan asked DaoWu again, "Master, please say it to me right away. If you don't, I shall hit you."

DaoWu said, "If you want to hit me, you can hit me. But I will never say."

Thereupon JianYuan actually hit him.

This is just where I should apply effort

Later DaoWu passed away. JianYuan went to ShiShuang QingZhu (石霜慶諸: 807-888), who had been a senior disciple of DaoWu, and told him what had happened.

ShiShuang said, "I won't say alive, and I won't say dead."

JianYuan said, "Why won't you?"

ShiShuang said, "I won't say, I won't say."

With these words, JianYuan came suddenly to an insight.

One day, JianYuan took a hoe and walked in the Dharma-hall from east to west and west to east.

ShiShuang said, "What are you doing?"

JianYuan said, "I am seeking the sacred bones of the late master."

ShiShuang said, "Giant billows far and wide; whitecaps swelling up to heaven. How can you find sacred bones of your late master?"

JianYuan replied, "This is just where I should apply effort."

ZEN ANECDOTES

Translated by Lucien Stryk & Takashi Ikemoto [池本喬 1906-1980]

In: ZEN: Poems, Prayers, Sermons, Anecdotes, Interviews

Anchor Books, Doubleday & Co., Inc., Garden City, New York, 1963

(Addenda by Gabor Terebess)

38

At the death of a parishioner, Master Dogo (道吾圓智 Daowu Yuanzhi, 769-835)

accompanied by his disciple Zengen (漸源仲興 Jianyuan Zhongxing, ?-?) visited

the bereaved family. Without taking the time to express a word of sympathy,

Zengen went up to the coffin, rapped on it, and asked Dogo, "Is he really dead?"

"I won't say," said Dogo.

"Well?" insisted Zengen.

"I'm not saying, and that's final."

On their way back to the temple, the furious Zengen

turned on Dogo and threatened, "By God, if you don't

answer my question, why, I'll beat you!"

"All right, beat away."

A man of his word, Zengen slapped his master a good

one.

Some time later Dogo died, and Zengen, still anxious

to have his question answered, went to the master

Sekiso (石霜 / 慈明 楚圓 Shishuang/Ciming Chuyuan, 986–1039)

and, after relating what had happened, asked the same

question of him.

Sekiso, as if conspiring with the dead Dogo, would

not answer.

"By God," cried Zengen, "you too?"

"I'm not saying, and that's final."

At that very instant Zengen experienced an awakening.