ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

賣茶翁 Baisaō (1675-1763)

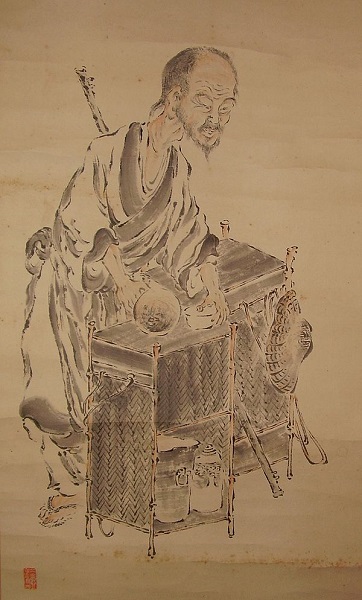

Baisaō with his portable tea stand,

as depicted in a gently comical caricature painting

of the late 19th–early 20th century

Baisaō was a Japanese Buddhist monk of the 黄檗 Ōbaku school of Zen Buddhism, who became famous for traveling around Kyoto selling tea. His tea shop was very influential in Kyoto especially with artists and philosophers. 賣茶翁 Baisaō, "Old Tea Seller," was a name he picked up from his act of making tea. His Zen priest name was 月海元昭 Gekkai Genshō. Later in his life, he denounced his priesthood and adopted the lay name of 高遊外 Kō Yūgai.

Baisaō was an inspirational and unconventional figure in a culturally rich time period in Kyoto. A poet and Buddhist priest, he left the constrictions of temple life behind and at the age of forty-nine traveled to Kyoto, where he began to make his living by selling tea on the streets and at scenic places around the city. Yet Baisaō dispensed much more than tea - though he would never purport to be a Zen master, his clientele, which consisted of influential artists, poets, and thinkers of the time, considered a trip to his shop as having a religious importance. His large bamboo wicker baskets, full of tea utensils, provided Baisaō and his customers with an occasion for conversation and poetry, as well as exceptional tea.

Included in his writings is a remarkable but little-known document, essential to understanding his life, that contains Baisaō's response to a customer's inquiry as to why he abandoned the Buddhist priesthood for a tea-selling life. These poems, memoirs, and letters trace his spiritual and physical journey over a long life.

This book includes virtually all of his writings translated for the first time into English, together with the first biography of Baisaō to appear in any language. It is bound to establish Baisaō's place alongside other Zen-inspired poets such as Basho and Ryokan.

François Lachaud, Le vieil homme qui vendait du thé: Excentricité et retrait du monde dans le Japon du XVIIIe siècle (Les conférences de l'École Pratique des Hautes Études 4)

Paris: Les Editions du Cerf, 2010. 153 pp

Le Vieil Homme qui vendait du thé est un ancien moine bouddhiste, revenu à la vie laïque, qui trouve dans cette nouvelle activité l'occasion à la fois de " se retirer du monde " et de poursuivre des échanges agréables avec ceux qui fréquentent sa boutique, attirés par sa sagesse et sa culture. Nous sommes au Japon, à Kyoto, au XVIIIe siècle, à l'apogée de l'ère d'Edo. A travers cet " excentrique exemplaire " - Socrate extrême-oriental - et avec l'étude de la civilisation d'Edo, c'est un pan extrêmement attachant de la culture japonaise que nous décrit avec brio et enthousiasme François Lachaud, proposant ainsi une réflexion passionnante sur les rapports entre excentricité et ascèse, qui met à mal les clichés occidentaux.

Waddell, Norman

The old tea seller: The life and poetry of Baisaō.

The Eastern Buddhist 17: 93–123. (1984)

PDF: Searching for the Spirit of the Sages: Baisaō and Sencha in Japan

by Patricia J. Graham

1996

Portrait of Baisaō on a Footbridge by 伊藤若冲 Itō Jakuchū (1716-1800)

Portrait of Baisaō on a Footbridge by 伊藤若冲 Itō Jakuchū (1716-1800)

PDF: The Old Tea Seller: Life and Zen Poetry in 18th Century Kyoto

Baisaō by Norman Waddell

Counterpoint Press, Berkeley, 2008, 222 p.

Extract :

The man known as Baisaō, old tea seller, dwells by the side of the Narabigaoka Hills.

He is over eighty years of age,

with a white head of hair and a beard so long it seems to reach to his knees. He puts his brazier, his stove, and other tea implements in large bamboo wicker baskets and ports them around on a shoulder pole.

He makes his way among the woods and hills, choosing spots rich in natural beauty. There, where the pebbled streams run pure and clear, he simmers his tea and offers it to the people who come to enjoy these scenic places.

Social rank, whether high or low, means nothing to him. He doesn't care if people pay for his tea or not. His name now is known throughout the land.

No one has ever seen an expression of displeasure cross his face, for whatever reason. He is regarded by one

and all as a truly great and wonderful man.

-Fallen Chestnut Tales

Life of Baisaō

INTRODUCTION

IN THE FOURTH month of 1724 the priest Gekkai GenshO, then in his late forties, left the Zen temple in the castle town of Hasuike on the southernmost Japanese island of Kyushu,

where he had served for thirty-eight years, and set out for the capital at Kyoto, some five hundred miles distant. After a decade or so which he apparently spent wandering around the Kyoto/ Osaka region, he took up residence in a small dwelling on the banks of the Kamo River in Kyoto, earning a living at the age of sixty by selling a new type of tea known as sencha, made by infusing leaves in a teapot.

He soon became a familiar figure around the capital, known simply by the sobriquet he had adopted, Baisaō, "the Old Tea Seller." His shop was frequented by ordinary citizens as well as by many of those at the center of the city's artistic, literary, and intellectual life. Baisaō forged lasting friendships with his remarkable clientele of leading poets, writers, painters, calligraphers, and scholars of the Edo period, a set of congenial spirits who made early eighteenth-century Kyoto one of the finest and most interesting cities anywhere in the world.

In addition to selling tea at his place of residence, Baisaö was soon taking his shop outdoors. Shouldering his tea equipment, balanced in large portable bamboo-wicker baskets on the ends of a carrying pole, he could set up for business wherever he wished, choosing sites among the many celebrated scenic locales in Kyoto and the surrounding hills.

Baisaō did not charge a fixed price for his tea, relying instead on donations left by customers. Although these alms usually were enough to buy the small amount of rice he needed to sustain himself and were occasionally supplemented by gifts of staples such as miso and shoyu, his poems describe times of great extremity when, foodless and penniless, he was reduced to begging.

For the first ten years of his residence in Kyoto, Baisaō remained a priest, going against Buddhist regulations pointedly forbidding clerics to earn their own living. 'When at the age of sixty-seven circumstances arose that obliged him to leave the priesthood, forfeit his Buddhist names, and revert to lay status, he adopted the secular name Kö Yugai, which he and his friends often shortened to Layman Yugai.

In his eighties, Baisaō was crippled by severe back pains that made it impossible to continue carrying his tea equipment atound the city. He burned his favorite carrying basket and other tea utensils-to keep them, he said, from "falling into vulgar hands"- I and began to eke out a living from writing calligraphy and from selling tea at his shop, which now, after many moves, was located in the village of Shogo-in in Kyoto's eastern suburbs.

In the seventh month of 1763, Baisaō passed away peacefully at the age of eighty-eight. Shortly before, his friends had put in his hands a copy of the Baisaō Gego ("Verses and Prose by the Old Tea Seller"), a collection of Chinese writings he had composed in the course of his tea-selling life, which they had prepared and printed.

The earliest account of Baisaō's life is the one compiled by his young friend Daiten Kenjo, a Shokoku-ji priest, as an introduction for the Baisaō Gego. This became the basic source for most of the brief sketches of Baisaō that appeared prior to the twentieth century. In piecing together the present work I have followed quite closely the chronology established by the modern Baisaō scholar Tanimura Tameumi. Thanks to new material in letters and inscriptions found in private collections and sales catalogs that I have been able to discover in the decades since Tanimura's work was published, I believe that I have been able to emend or clarify his research in some places.

The present volume consists of two parts, the first a life of Baisaō, and the second, translations of Baisaō's poetry and prose, which include all of the works in the Baisaō Gego collection of poetry and prose published before his death, as well as most of the eleven additional verses that appear in Baisaō, the standard edition of his writings edited by Fukuyama Chogan and published in 1934. Of Baisaō's prose writings, the most important are the Baizan shucha furyaku ("A Brief History of the Tea Seeds Planted at Plum Mountain"), a very concise history of Japanese tea; and the Taikyaku Genshi ("A Statement of My Views in Reply to a Customer's Questions"), in which Baisaō explains at some length his reasons for taking up his tea-selling life.

Baisaō's religious career can be divided into three periods: the period of religious training, which continued until roughly his thirty-second year; the second period, ending in his fifty-seventh year, during which he served as temple supervisor, and later as de facto abbot at Ryushin-ji in Hasuike; and the third period, which covers the years he spent in Kyoto as the Old Tea Seller. The following biographical sketch focuses on the third period:

in addition to being the most interesting part of his life, it is the only one for which any source materials exist.…

Making the busy streets my home

right down in the heart of things

only one friend shares my poverty

this single scrawny wooden staff.

Having learned the ways of silence

within the noise of urban life

I take life as it comes to me

and everywhere I am is true.…

Rambling free beyond the world

enjoying the natural shapes of things

a shaggy eight-year-old duffer

scraping out a living selling tea.

He escapes starvation, barely,

thanks to a section of bamboo,

a tiny house with a window hole

provides all the shelter he needs.

Outside, carts and horses pass

annulling both noise and quiet

inside, easy talk at the stove

banishes notions of host and guest.

He lives under a row of tall pines

beside a temple of guardian sages

where the pine breeze sweeps clear

the dust of fame and profit.…

Set out to transmit

the teaching of Zen

revive the spirit

of the old masters

settled instead for

a tea-selling life.

honor, disgrace

don't concern me

the coins that gather

in the bamboo tube

will stop Poverty

from finishing me off.…

A gift of “immortal buds” sent from an old friend

“first spring picking from the Ekkei fields,” he said

Opening the packet, color and fragrance filled the room,

Proud ‘banners and lances' of outstanding quality.

Clear water dipped at the banks of the Kamo

Well boiled on the stove, just right for new tea.

The first sip revealed an incomparable taste,

Purifying sweetness refreshing the soul.

No need wasting time on ‘butterfly dreams,'

Rising up, utterly cleansed, beyond the world,

I smile, not a single word in my dried-up gut,

Just a ‘wondrous meaning' beyond all doctrine.

I've been poor so long, pinched with hunger,

Now a kind gift to soothe my parched throat,

Dewdrops so sweet they put manna to shame:

The fresh breeze rises round me, lifting me upward.

It doesn't take seven cups like Master Lu says,

My guests get old Chao-chou's ‘one-cup tea';

And whoever can grasp the taste in that cup

Whether stranger or friend, knows my true mind.

Sake fuels the vital spirits, works like courage,

Tea works benevolently, purifying the soul.

Courageous feats that put the world in your debt

Couldn't match the benefit benevolence brings.

A tea unsurpassed for color, flavor, and scent,

Attributes the Buddhists like to call “dusts,”

But only through them is the true taste known,

They are the Dharma body. Primal suchness.…

Pure water from a clear spring

simmering over the clay stove

battered robe and tattered cap

brown with fume and tea smudge.

Don't think I'm some old gaffer

with a wild-eyed love for tea.

My purpose is to awaken you

out of your worldly sleep.…

I moved this morning

to the center of town

waist deep in worldly dust

but free of worldly ties.

I wash my robe and bowl

in the Kamo's pure stream

the moon a perfect disc

rippling its watery mind.…

Three Verses on a Tea-Selling Life

I.

I'm not Buddhist or Taoist

not a Confucianist either

I'm a brownfaced whitehaired

hard-up old man.

people think I just prowl

the streets peddling tea,

I've got the whole universe

in this tea caddy of mine.II.

Left home at ten

turned from the world

here I am in my dotage

a layman once again;

A black bat of a man

(it makes me smile myself)

but still the old tea seller

I always was.III.

Seventy years of Zen

got me nowhere at all

shed my black robe

became a shaggy crank.

now I have no business

with sacred or profane

just simmer tea for folks

and hold starvation back.…

Pain and poverty

poverty and pain

life stripped to the bone

absolute nothingness

only one thing left

a bright cold moon

in the midnight window

illumining a Zen mind

on its homeward way.…

Ahh! this stone-blind jackass

with his strange kink in the brain

he turned monk early in life

served his master, practiced,

wandered to a hundred places

seeking the Essential Crossing.

Deafened by shouts

beaten with sticks

he had a hard time of it

weathering all that snow and frost

still couldn't even save himself;

big-headed, brazen-faced

made a great fool of himself.

Growing old he found his place

became an old tea seller

begged pennies for his rice.…

The Zen Monk Kyō Has Changed His Name to Mujū Dōryū.

I Wrote This Verse to Celebrate The Great Prospects That Lie Before Him

Unwillingness to remain in the ruts of former Buddha patriarchs

Unsurpassed aspiration and fierce passion to achieve the Way

These are precisely the qualities found in a true Zen monk

Attained the very moment you "have been there and back.…

When the mind is truly at peace,

wherever you are is pleasant,

Whether you live in a marketplace

or in a mountain hermitage.…

Pine trees rise through cloud

soar up into the blue skies,

bush clover spangled with dewdrops

sways in the autumn breeze;

As I dip cold, pure water

at the edge of the stream,

a solitary white crane

comes lolloping my way.…

This rootless shifting east and west

I can't suppress a smile myself

but how else can I make

the whole world my home.

If any of my old friends

come around asking

say I'm down at the river

by the Second Fushimi Bridge.…

Book reviewed by Joseph S. O’Leary, Sophia University

http://nirc.nanzan-u.ac.jp/nfile/3046This monograph is based on lectures given in the context of Jean-Noel Robert’s

chair of Japanese Buddhism at the Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes. It focuses on

the figure of Baisaō 賣茶翁 (Kō Yūgai 高遊外, 1675–1763), a widely admired “eccentric”

(kijin), whose career has been presented in English by Norman Waddell (1984,

2008). Such marginal figures acquired literary and spiritual prestige in the conformist

society of the Edo period. Since Baisaō was not a prominent intellectual, writer, or

religious leader, he is likely not to be on the radar screen of Western scholars of

Japanese philosophy and religion, who may consign him to the vague realm of aesthetics.To illuminate his philosophical and religious significance, Lachaud refers to a

line of literary hermits stretching from Kamo no Chōmei (1155–1216) to Nagai Kafū

(1879–1959), as well as to Chinese poets and artists of the Song period and earlier,

who provided a model for combining eremiticism with the conviviality of a literary

coterie. Sinophilia prevailed among Edo practitioners of Chinese verse (kanshi),

calligraphy, go, playing the kin, and painting (32). Neo-Confucianism had more

appeal than Buddhism. Baisaō was an adherent of Obaku Zen, which communicated

a fresh view of a living Chinese culture to the Japanese. Lachaud does not

refer to the Rinzai Zen poet and eccentric Ikkyū Sojun, perhaps because Baisaō is

remote from the tradition of libertine monks. Rather he stands for a rough-hewn,

natural lifestyle, emblematized in his championing of sencha 煎茶 in opposition to

the refinements of the tea ceremony.Lachaud also refers, perhaps over-generously, to Western figures such as Cicero,

John of the Cross, Izaac Walton, La Rochefoucauld, Nerval, Champfleury, Cezanne,

Heidegger, Kerouac, and Ginsberg, in order to show that the contemplative freedom

of Japanese eccentrics has universal value. He reports that the spirit of the

eccentrics is alive in Japan today: “The terms ‘slow life,’ ‘healing,’ and iyashi—the

autochthonous translation of the preceding term—and on everyone’s lips and in

the front window of bookshops and shops for incense, aromatherapy, and New Age

accessories” (18–19). These references seem to me to dilute the specific character

of Baisaō and his Edo context. But Lachaud has succeeded in showing that Baisaō

stands for more than a period charm and quaintness, and that he can profitably be

interrogated in connection with central themes of religious thought.One of Baisaō’s foremost admirers was Ueda Akinari (1734–1809), who also

claimed kijin status and took up Baisaō’s critique of the formalism of the tea ceremony

and his championing of the freedom and naturalness of sencha. He remarked

that Baisaō hid himself behind his role of tea seller to laugh at the world, from the

perspective of enlightenment (109–10). He presents Baisaō in fictional guise as one

alien to the tortuous ideas of Buddhist and Confucian scholasticism: “Here, my

heart is purified of its own accord at the stone mouth of my hermitage spring, and

thinking neither of life nor of death, I know neither cold nor heat” (112). Another

interesting connection is with the painter Itō Jakuchū (1716–1800), famed for his

“vegetable nirvana” scenes. This way of living Buddhism as a comedy, yet without

irreverence, is something for which few Western or Christian parallels can be found.

Some errata: on page 34 read Karaki Junzō, not Jūzō; a word is missing on page

84, 1.7; the reference on page 80 to Kinsei kijin den, ii, pages 78–80, should be to i,

pages 96–8. The pages in Chinese reproduced on pages 92 and 95 do not connect

very smoothly with the passages translated.

Book reviewed by Vladimir K.

http://www.thezensite.com/ZenBookReviews/The_Old_Tea_Seller.htmlSometimes it seems that eccentricity is an essential characteristic of Zen masters. Zen literature is littered with stories of eccentric characters and baffling actions. One of my favourites is the story of Shūhō Myōchō (1282-1337) who had a breakthrough in 1308 and then spent 20 years under Gojō Bridge in Kyoto living with beggars. Eventually Emperor Hanazono (r. 1308-1318) wanted him to begin teaching and so he went to the bridge with a basket full of melons (apparently Myōchō's favourite food) and said to the beggars “Step up and take this melon without using your feet.” A beggar replied, “Give me a melon without using your hands,” and the emperor knew which of the beggars was the Zen master. Shūhō (later titled as Daitō Kokushi ) went on to becomea National Teacher and construct one of the great temples of Medieval Japan, Daitokuji.[1] Of course, whether the story is true historically or not is another question. Thomas Cleary has translated an entire collection of strange, eccentric behaviour of Zen masters, including the old tea seller, so there are many stories about these characters. Oddly enough, although Cleary has an entry on the old tea seller, he does not actually name him.[2] Perhaps this reflects how little was available in English about this marvellous eccentric until now.

Norman Waddell's new book has finally made available to English readers the whole story of Baisaō, the Old Tea Seller, and what an interesting story it is. The book is aimed at a general readership and is essentially in two parts: the life of Baisaō and an extensive translation of his poetry and other texts. Letters of Baisaō are scattered throughout the bibliography, as are some of his poems, giving an insight into not only his thoughts, but also his trials and tribulations. There is also an extensive section of Notes to the biography but, as Waddell himself says, these “can be read with the text, afterwards, or disregarded entirely.” (p xi)

Baisaō was born in 1675 in the southern Japanese island of Kyushu. As the son of one of the intellectual elites of the area, he received an extensive education and when he was eleven, became a Buddhist priest in the Ōbaku sect, taking on the name Gekkai Genshō. In 1687 he travelled with his master, Kerin Dōryū, to Mampuku-ji, the headquarters of Ōbaku Zen and on this trip he first tasted the delights of the capital, Kyoto. One of the places the two Zen monks visited was Kōzan-ji, on the outskirts of Kyoto, where the first tea gardens in Japan were planted.

Like many Zen monks, Baisaō travelled extensively around Japan, spending various periods at his own temple, Ryūshin-ji, and when his master died, the abbotship went to a younger priest. When Baisaō was asked why he did not get the position, he humbly replied “because I have no wisdom or virtue”. (p 13) Although he was asked a number of times to take over the temple, he refused and at the age of forty-nine he set off for the capital, where he would spend the rest of his life.

Kyoto in the latter half of the eighteenth century was a remarkable city which Waddell brings to life. While the rest of Japan, including the capital city, Edo (modern Tokyo), suffered under the conservative rule of the Tokugawa shogunate which demanded discipline and stifled self-expression, Kyoto was far more liberal, allowing creativity and the arts to flourish. Writers, artists and scholars flocked to the city, breaking with the stultifying conservatism of the era. Surrounded on three sides by tree-covered hills of great beauty and with a population of some half a million, Kyoto was the second largest (and one of the most beautiful) cities on earth. It was in this atmosphere of exciting creativity that Baisaō settled.

At a time when Buddhist monks were viewed with some disdain, Baisaō stood out for his impressive skills as a poet and calligrapher with an extensive knowledge of Chinese literature, skills highly prized in Kyoto. Baisaō was held in high esteem by all who came in contact with him for his generosity, gentleness and his seemingly carefree life which rejected the established Buddhist hierarchy. Over time, he became one of the best known characters in a city full of eccentrics and artists. There were so many unconventional characters in Kyoto at this time that in 1788 a book was published, Eccentric Figures of Recent Times,where Baisaō played a prominent part.

At the age of sixty, Baisaō set up a small shop or perhaps just a stall (he called it a “snail dwelling” (p 20)) on a heavily travelled bridge which crossed Kyoto's Kamo River. At that time, itinerant tea sellers were from the lowest ranks of society and sold an inferior powdered tea. Baisaō, however, introduced sencha, a loose-leaf tea which was simmered in a pot and was considered a much higher grade of tea; a tea which with “one sip, you wake forever from your worldly sleep.” (p 41) Today we call this tea Japanese green tea. In fact, he did not actually sell his tea as he accepted only donations, saying “The price for this tea is anything from a hundred in gold to a half sen. If you want to drink free, that's all right too. I'm only sorry I can't let you have it for less.” (p 33) Later, he gave up his little ‘shop' and wandered Kyoto and the surrounding hills carrying his tea making implements on a bamboo carrying pole and setting up business wherever the landscape attracted him. He took on the sobriquet, Baisaō, the Old Tea Seller.

Baisaō's latter years were full of difficulty as old age and infirmity overtook him. The cold winters of Kyoto proved especially difficult for an old man with little money. Hunger and cold were companions. Although he was acknowledged as a Zen master, it was only in his latter years that he took on a small handful of students. Throughout his long life he continued writing poetry and creating highly-prized calligraphy. Just before he died at the ripe age of eighty-eight, his friends managed to present him with a printed collection of his writings, Baisaō Gego (“Verses and Prose by the Old Tea Seller”), confirming his importance in the cultural life of eighteenth century Kyoto.

Norman Waddell has brought us an important Japanese Zen poet who has been too long neglected. The biography is detailed and informative but Waddell has gone further and has translated all of Baisaō's published verse (including some taken from holograph manuscript) and prose, as well as many of Baisaō's letters and verse. Unlike the first half of the book, which has end notes to help the reader, the second half, which has the translations of Baisaō's writings, includes footnotes to help the reader negotiate some of the more obscure references with which modern Western readers may not be familiar. Scattered throughout the first section are letters and poems by Baisaō as well as delightful small reproductions of paintings of Baisaō, some with inscriptions by the Old Tea Seller and some examples of his calligraphy. Unfortunately, the reproductions do not do justice to the originals as they are too small to truly appreciate their beauty. But this is a small quibble with what is otherwise a fine book. With this work, Waddell has raised this previously unappreciated Zen poet to his rightful place alongside better known poets such as Bashō and Ryōkan. This book will stand as the definitive work on Baisaō for many years.

see Dumoulin, 1990, pp. 186-189

see Cleary, 1993, pp. 3-4References

Cleary, Thomas, 1993, Zen Antics, Shambhala, Boston

Dumoulin, Heinrich, 1990, Zen Buddhism, Volume 2: A History (Japan), Japan, trans. J.W. Heisig & P. Knitter, Macmillan, New York

Two quotes from Baisaō:

“The price for this tea is anything from a hundred in gold to a half sen.

If you want to drink free, that's all right too. I'm only sorry I can't let you have it for less.”“What's the tea seller got in his basket?

Bottomless tea cups?

A two-spouted pot?

He pokes around town for a small bit of rice,

Working very hard for next to nothing---

Blinkering old drudge just plodding ahead...

Bah!”

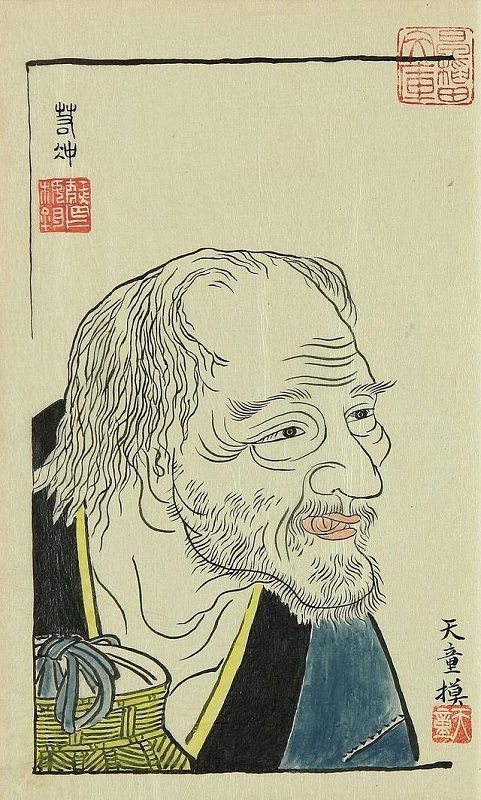

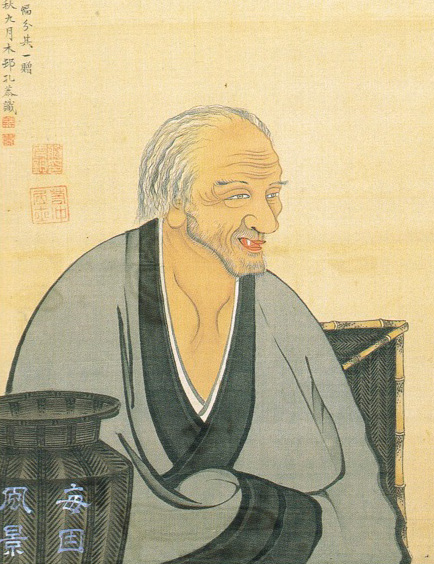

A portrait of Baisaō by 伊藤若冲 Itō Jakuchū

(1716-1800) and another portrait by

田能村竹田 Tanomura Chikuden (1777-1835)