ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

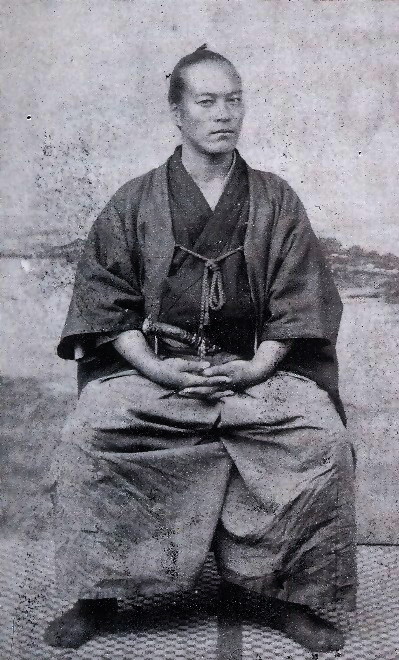

山岡鉄舟 Yamaoka Tesshū (1836-1888)

aka 小野鉄太郎 Ono Tetsutarō, 山岡鐵太郎 Yamaoka Tetsutarō, 山岡高歩 Yamaoka Takayuki

Tartalom |

Contents |

John Stevens

|

PDF: The Sword of No-Sword: Life of the Master Warrior Tesshu PDF: The Truth of the Ancient Ways: A Critical Biography of the Swordsman Yamaoka Tesshu 剣禅書 Ken Zen Sho, The Zen Calligraphy and painting of PDF: Yamaoka Tesshū, a Swordsman for Peace |

![]()

Yamaoka Tesshu was born in Edo (modern day Tokyo ) in 1836. At the time of his birth, he was known as Ono Tetsutaro. Later, he adopted the family name of Yamaoka from his spear instructor, who's sister he married.

Tesshu was born into a samurai family and began his study of swordsmanship when he was nine years old. Over time Tesshu studied a number of fencing styles and became highly proficient.

When he was twenty-eight, Tesshu was defeated by a swordsman named Asari Gimei and became his student. Although larger and younger, Tesshu could not match his teacher's mental state. During training sessions, Asari was known to force Tesshu all the way to the back of the dojo, then out into the street, knock him to the ground, and then slam the dojo door in his face. Confronted with this challenge, Tesshu increased his efforts in training and meditation continuously. Even when he was eating or sleeping, Tesshu was constantly thinking about fencing. He would sometimes wake up at night, jump out of bed, and get his wife to hold a sword so he could explore a new insight. Then, one morning in 1880, when he was 45 years old, Tesshu attained enlightenment while sitting in zazen. Later that morning he went to the dojo to practice Kendo with Asari. Upon seeing Tesshu, Asari recognized at once that Tesshu had reached enlightenment. Asari, declined to fence with Tesshu, acknowledging Tesshu's attainment by saying, “You have arrived.” Shortly after this, Tesshu went on to open his own school of fencing.

Tesshu was 6ft tall, unusual for a Japanese person of his time, and very athletic. He was a natural leader and very competitive. So intense was his practice of his three main pursuits (fencing, Zen, and calligraphy), that his nickname was Demon Tesshu . Tesshu was also famous for combining his competitive nature with his love of drinking.

Tesshu was a master calligrapher and is estimated to have created over 1,000,000 calligraphy paintings. His art works are considered important and are studied now, even as they were in his lifetime.

Tesshu's life bridged the time between feudal and modern Japan . Tesshu held a position as a bodyguard for the last Togugawa Shogun. Tesshu even played a role in the transition of power. Then Tesshu became a tutor for the Emperor Meiji during the emperor's early adulthood.

On one occasion the young emperor challenged Tesshu to a wrestling match. The emperor enjoyed sumo wrestling but he had acquired the inappropriate habit of challenging his aids to impromptu wrestling matches. On one occasion, following a bout of sake drinking, the emperor challenged Tesshu to wrestle. When Tesshu refused the challenge, whereupon the emperor tried to push and pull Tesshu, but the emperor found Tesshu to be immoveable. Then the emperor tried to strike Tesshu, but Tesshu moved slightly aside. The force of the emperor's blow caused him to fall down, whereupon Tesshu pinned the emperor to the ground. The emperor's other aids were furious with Tesshu and demanded that Tesshu apologize to the emperor. Tesshu asserted that he was in fact doing his duty and would commit suicide if the emperor requested, but he would not apologize. The emperor saw the wisdom of Tesshu's way and gave up (temporarily) both wrestling and drinking. From then on Tesshu was one of the emperor's most trusted advisors.

On another occasion, the emperor, observing how worn Tesshu's clothing was, gave Tesshu some money to buy new clothes. Tesshu, however, had little regard for material possessions and gave the money to the numerous poor people who sought the hospitality of his household. The next time Tesshu appeared before the emperor, he was wearing the same old clothes.

"What became of the new clothes?" asked the emperor. Tesshu responded back, “They went to you majesty's children.”

Tesshu died from stomach cancer, in the year 1888, at the age of fifty-three. On t he day before he died, Tesshu noticed that there were no sounds of training to be heard from his dojo. When Tessu was told that the students had canceled training to be with him in his last hours, he ordered them to return to the dojo saying, “Training is the only way to honor me!”

一刀正伝無刀流 Ittō Shōden Mutō-ryū is a school of Japanese swordsmanship (kenjutsu) created by Yamaoka Tetsutaro Takayuki, more commonly known as Yamaoka Tesshū.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Itto_Shoden_Muto-ryu• Founder : Yamaoka Tesshū / Yamaoka Tetsutaro Takayuki

• 2nd Head : Kagawa Zenjirō 香川善治郎 (1848-1921)

• 3rd Head : Ishikawa Ryūzō 石川龍三

• 4th Head : Kusaka Ryūnosuke 草鹿龍之介 (1892-1971)

• 5th Head : Ishida Kazuto 石田和外 (1903-1979)

• 6th Head : Yasumasa Murakami 村上康正

• 7th Head : Izaki Takehiro 井﨑武廣

Itto-ryu Kenjutsu: An Overview

by Meik Skoss

http://www.fightingarts.com/reading/article.php?id=370Introduction

Itto-ryu kenjutsu is one of the most significant schools of Japanese swordsmanship ever developed. It was chosen as one of the official kenjutsu ryu of the Tokugawa shogunate (Shinkage-ryu being the other). Many of the daimyo (lords of major feudal domains) throughout Japan also adopted it as an otome ryu (official system) for their own retainers.

In more recent times, the men instrumental in creating the technical curriculum of kendo (modern Japanese fencing, or swordsmanship with mock weapons made of bamboo) were greatly influenced by Itto-ryu theory and technique. Several of the men charged with creating the Dai Nippon Teikoku Kendo Kata, forerunner of today’s Nihon Kendo Kata, were exponents of Hokushin Itto-ryu and they conferred with exponents of other branches of the Itto-ryu in order to create the forms that became the technical standard for modern kendo.

Itto-ryu has preserved a greater number of its derivative styles than any other school of kenjutsu and is today one of the most viable “families” of classical Japanese swordsmanship. There are six lines of Itto-ryu still being practiced today, with a sufficient number of exponents and level of skill to ensure that their art will be passed on intact to future generations: Ono-ha Itto-ryu, Mizoguchi-ha Itto-ryu, Nakanishi-ha Itto-ryu, Kogen Itto-ryu, Hokushin Itto-ryu, and Itto Shoden Muto-ryu.

The Development of Itto-ryu Kenjutsu

Itto-ryu kenjutsu was created during the late Sengoku jidai (Warring States period, 1467–1568) by a man named Ito Ittosai Kagehisa. At the age of thirteen, Ittosai is said to have floated on a piece of timber across the Bay of Sagami to the village of Ito, on the Izu Peninsula. He supposedly lived under the floor of a local shrine and practiced swordsmanship on his own. After repelling some bandits who had threatened the village, grateful residents gave him some money and one of the swords that had been dedicated to the shrine, enabling him to begin his search for proper instruction. He studied Chujo-ryu tojutsu (swordsmanship) with Kanemaki Jissai, a student of Toda Seigen, who was famous for his superlative short sword technique, and then embarked on musha shugyo (an itinerant warrior’s journey, made for the purpose of testing or improving one’s martial skills), traveling in the Kansai and Kanto regions.

During this “warrior journey,” Ito had several experiences, when he spontaneously performed a movement under the stress of combat, that influenced his thinking about swordsmanship, and he later incorporated these insights into his system. The techniques he created, zetsumyo ken and muso ken, refer to the mystic, “ineffable,” and “miraculous” nature of highly skilled swordsmanship, where trained actions take place without conscious thought. After further training and study, Ito combined the Chujo-ryu teachings with his own personal discoveries to create his own system of kenjutsu. He named it the Itto-ryu (One Sword Style), a reflection of his belief that the essence of swordsmanship could be stated in a simple phrase, itto sunawachi banto, “one sword [technique] gives rise to ten thousand sword [technique]s” which was in turn derived from an understanding of the underlying essentials of personal combat: maai (distancing), hyoshi/choshi (timing/rhythm), hasuji (literally, “blade line,” trajectory and/or targeting), and kurai (mental and physical stance or preparedness).

General Background

Ono-ha Itto-ryu

Ono-ha Itto-ryu is recognized as the senior line of the Itto-ryu styles of swordsmanship. It was founded by Ono Jiroemon Tadaaki, who succeeded Ito Ittosai Kagehisa as the second head of Itto-ryu kenjutsu. Originally, his name was Mikogami Tenzen, and Ono was the name he took after becoming the head of the school

An example of how the Ono-ha Itto-Ryu shidachi (left) “cuts through” uchidachi’s attack and controls the center line.

After Tadaaki was appointed kenjutsu shinan-yaku (instructor in swordsmanship) to Ieyasu’s son, the second Tokugawa shogun, Tokugawa Hidetada, Itto-ryu became one of two official kenjutsu schools of the Tokugawa shogunate. He also served Iemitsu, the third shogun, in this capacity.

The fourth headmaster, Tadakazu, instructed the lord of the Tsugaru han (domain, in present-day Aomori Prefecture), Tsugaru Echigo-no-kami Nobumasa, in the entire system of the Ono-ha Itto-ryu and established a separate Tsugaru line. Other feudal lords and senior retainers throughout Japan also studied the ryu, and this served to increase its reputation and prestige in both the capital and provincial castle towns.

Tsugaru Tosa-no-kami Nobutoshi, second lord of Tsugaru, returned the transmission to the Ono family when he instructed both Ono Tadahisa (who died soon after) and Tadakata. After this time, both the Ono and the Tsugaru families transmitted the main, or orthodox, line of Ono-ha Itto-ryu.

In the Kansei period (1789–1801), the seventh head of the school, Ono Tadayoshi, taught a Tsugaru retainer by the name of Yamaga Hachirozaemon Takami the entire Ono-ha Itto-ryu curriculum and after that, the Tsugaru and Yamaga families worked together to transmit the system. This semi-formal collaboration continued until the Taisho period (1912–1926), when Sasamori Junzo, a well-known kendoist, Christian minister, and educator, who later became an influential politician noted for his work for international peace, inherited the ryu. The seventeenth generation headmaster, active today, is Junzo’s son, Takemi, also an ordained minister and prominent educator. Ono-ha Itto-ryu is also practiced independently, outside the purview of the mainline of the ryu, by kendo teachers, some daito-ryu organizations and other exponents throughout Japan, and is thus probably the most widely disseminated form of Itto-ryu today.

Mizoguchi-ha Itto-ryu

The founder of Mizoguchi-ha Itto-ryu kenjutsu was a man named Mizoguchi Shingoemon Masakatsu. He had studied with Ono Jiroemon Tadatsune, the second head of Ono-ha Itto-ryu, before creating his own style. In the middle of the Edo period (1600–1868), a student of Mizoguchi’s named Ito Masamori visited the Aizu han (in present-day Fukushima Prefecture), where he taught one of the clan retainers, Edamatsu Kimitada. Masamori, however, left before teaching the entire system to Edamatsu.

The cutting movement that follows shidashi’s opening movement to uchidachi’s left side. Shidachi has used the force of uchidachi’s thrust to turn around the axis of the attack.

Edamatsu, in turn, taught Ikegami Jozaemon Yasumichi, who later went to Edo (present-day Tokyo) on his daimyo’s orders to continue his training in swordsmanship. Ikegami studied not only Mizoguchi-ha Itto-ryu, but other kenjutsu styles as well, though it is not recorded which styles these were. Later, with more training and experience, Ikegami incorporated his ideas and experience in Mizoguchi-ha Itto-ryu and other systems and founded his own variation of the system; this then became the Aizu line of Mizoguchi-ha Itto-ryu kenjutsu, which was passed down to warriors of the domain. Because of the partial nature of the original transmission, and subsequent developments in the art as it was practiced in the Aizu-Wakamatsu area, there are said to be significant differences between Mizoguchi’s original art and that practiced by swordsmen of the Aizu han. The original line of the ryu has long been lost, however, so it is difficult to tell just what these differences are. Presently, the Fukushima prefectural and local kendo federations are responsible for practicing and transmitting the art to future generations.

Nakanishi-ha Itto-ryu

Nakanishi-ha Itto-ryu is probably closer to Ono-ha Itto-ryu, from which it is derived, than any other branch of Itto-ryu kenjutsu. The founder, Nakanishi Chuta Tanesada, studied with either the fifth generation headmaster of Ono-ha Itto-ryu, Ono Jiroemon Tadakata, or Ono Jiroemon Tadakazu, the sixth headmaster, and then left to establish his own style, which he named after himself (-ha meaning faction or school). His son, Nakanishi Chuzo Tanetake, succeeded him and introduced the use of bogu (protective equipment) and shinai (bamboo swords) in regular practice. Other schools of kenjutsu, notably Shinkage-ryu, Nen-ryu, and Tatsumi-ryu used a slightly different type of bamboo training sword in order to prevent or reduce injuries, but the equipment introduced by Tanetake led to the Nakanishi-ha’s rapid popularization, as it allowed exponents to train more freely and to engage in free-style matches resembling the competitive sport-form of modern kendo.

Over the years, many famous swordsmen have come from Nakanishi-ha Itto-ryu, some of them going on to establish ryu of their own. Among them are such notable warriors as Terada Gouemon (founder of Tenshin Itto-ryu), Shirai Toru (Terada’s successor), Takayanagi Matashiro Toshitatsu (or Yoshimasa, the founder of Takayanagi-ha Toda-ryu), Asari Yoshinobu (the teacher of Yamaoka Tesshu), and Chiba Shusaku (founder of Hokushin Itto-ryu). More recently, the Meiji-period headmaster of Nakanishi-ha Itto-ryu, Takano Sazaburo Toyomasa, a prominent educator, worked to develop both the technical and philosophical aspects of the modern art of swordsmanship and establish it in the public school system. He was also one of the men instrumental in refining the Nihon Kendo Kata, and he helped to find a place for kendo in modern society.

Kogen Itto-ryu

Kogen Itto-ryu kenjutsu is perhaps most famous as the ryu studied by the mad swordsman in the novel and film titled Daibosatsu Toge (the English title is “Sword of Doom”). It is an amalgamation of the household martial traditions of the Henmi family and Mizoguchi-ha Itto-ryu. Kogen Itto-ryu was founded by Henmi Tashiro Yoshitoshi, a descendant of a branch of the Takeda family, who are themselves descended from the Emperor Seiwa through Minamoto no Tsunemoto and Shinrasaburo Minamoto no Yoshimitsu (also in the lineage of Daito-ryu aikijujutsu). The name of the ryu is derived by combining the first character of Kai province, where the Takeda family lived (in present-day Yamanashi Prefecture; the character is pronounced “ko”), with that of their ancestral family (Minamoto is one of the most prestigious names to have in one’s lineage; pronounced “gen”), and an acknowledgment of the Itto-ryu’s contribution to this school of swordsmanship.

Kogen Itto-ryu developed as a discrete style of kenjutsu when an exponent of the Aizu Mizoguchi-ha Itto-ryu, Sakurai Gosuke Nagamasa, came to the Chichibu area (present-day Saitama Prefecture) and taught Henmi Yoshitoshi the techniques of his style. Sakurai came to acknowledge the technical superiority of his erstwhile student by later becoming a disciple of the Kogen Itto-ryu, accepting Henmi as his teacher. He stayed with the Henmi family for years, was cared for by them in his old age, and is buried in the Henmi family cemetery near their home.

Entrance to the Yokukan Dojo at the Henmi family home in Saitama Prefecture

The Henmi family was well known as a family of strong swordsmen, but they were not retainers of a particular lord and did not serve or live in a joka machi (castle town). The family farmed its own land and taught people who came to the area for instruction. Students generally trained in the morning and evening, and worked in the fields during the afternoon, trading their labor for tuition.

The dojo is in a typical old-style nagaya (long building) to the front of their house, where the Henmis established the Yobukan Dojo, which became famous throughout the province. Farming equipment is kept in a number of small storage rooms on the left as one goes through the gate; the dojo is to the right.

The current dojo was built more than two hundred years ago by the founder and is not a terribly large space, perhaps fifteen meters long and five meters wide. An old kago (palanquin) is kept up in the rafters. Old farming equipment (some of it for silkworm cultivation) is also stored there. A large door leads in from the earthen courtyard. As one looks toward the “front” of the dojo, there is a small raised shihan shitsu (room for the teachers) off to the left, covered with straw mats; in that room is an image of Marishiten, to which members of the dojo bow at the beginning and end of training. A couple of spears and naginata, used for special demonstrations, are kept over the door of the shihan shitsu; otherwise, trainees bring their own equipment with them and nothing is left at the dojo. Currently, Henmi Chifuji serves as the ninth headmaster of the ryu.

Hokushin Itto-ryu

The Hokushin Itto-ryu was founded by Chiba Shusaku Narimasa, one of the most famous swordsmen of the late Edo period. He originally studied his family’s martial art, the Hokushin Muso-ryu, and later studied Itto-ryu kenjutsu with Nakanishi Chubei Tanetada and Asari Matashichiro Yoshinobu. After undergoing years of training, he traveled around the country, studying the strong points of different schools and incorporating them into his own art. Chiba founded his own style when he came to believe traditional Itto-ryu techniques and training methods he had learned in the Asari and Nakanishi dojo lacked essential elements. In naming his school, he honored both his family tradition and the Itto-ryu that formed the core of his training by calling it the Hokushin Itto-ryu.

The Gembukan Dojo that Chiba opened in the Kanda area was one of the largest in nineteenth-century Edo, and Hokushin Itto-ryu became one of the most representative schools of the time, along with Jikishinkage-ryu, Kyoshin Meichi-ryu, Shingyoto-ryu, and Shinto Munen-ryu. It was located just around the corner from the Tenjin Shinyo-ryu jujutsu dojo of Iso Mataemon Masatari; the men were good friends and co-operated closely, and many of their trainees belonged to both dojo.

The ryu was also very closely allied with the Tokugawa family of Mito as an official school of the domain. It had become affiliated with Shin Tamiya-ryu iaijutsu which was also taught there; today the two schools are being taught at the Mito Tobukan Dojo, one of the premier training venues for kendo in the Kanto area, under the direction of the Kozawa family.

Itto Shoden Muto-ryu

Yamaoka Tetsutaro Takayuki, more commonly known as Tesshu, was one of the most remarkable swordsmen of the nineteenth century. Indeed, his place is probably assured among the greatest swordsmen of Japanese history, even though he never used his sword in anger. A devotee of Zen, an accomplished artist and calligrapher, he studied a number of ryu over the years, most notably Ono-ha Itto-ryu and Nakanishi-ha Itto-ryu. Tesshu, in fact, received the full transmissions of both the Nakanishi line and the Ono-ha Itto-ryu from their respective headmasters. In creating his own line of transmission, he named it the Itto Shoden Muto-ryu to emphasize that he was passing on the correct transmission of Itto-ryu principles and techniques. The term “Muto” (No-Sword) refers to the realization that Yamaoka attained through years of meditation that the difference between Sword and Self, and between oneself and one’s opponent is illusory and that the underlying unity of all is the most important thing in swordsmanship.

Today, there are very few exponents of Yamaoka’s school, most likely because its training methods are so severe. It is now practiced in Kanazawa Prefecture, on the Japan Sea side of Japan. Murakami Yasumasa, who learned from a late Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, Ishida Kazuto, is the sixth generation head of the school.

Distinguishing Characteristics

Ono-ha Itto-ryu

Ono-ha Itto-ryu kenjutsu has an extensive curriculum, with more than one hundred fifty techniques. Both the odachi (long sword) and kodachi (short sword) are studied in sets covering both theoretical and practical aspects of swordsmanship. All of the waza are suhada kempo (unarmored swordsmanship), although they can be easily adapted to techniques done in armor (kaisha kempo).

The central principle of Itto-ryu kenjutsu is expressed in the phrase itto sunawachi banto, “one sword is ten thousand swords”; that is, if one understands swordsmanship’s fundamental principles, one technique embodies and informs all other techniques and situations a swordsman might encounter. The signature waza of the Itto-ryu is kiriotoshi, which entails allowing the opponent to attack at will. The Itto-ryu exponent waits for the attack to develop, then cuts straight through the center of the enemy’s body and attacking motion, overriding his sword and disrupting the attack before it can be completed. Many, perhaps most, of the techniques end with a full-impact cut to the wrists or forearms, which are raised in the jodan position. To withstand the force of this final blow, the uchidachi (the individual acting as the attacker) wears a special pair of articulated deerhide gauntlets that are very thickly padded. These are known as onigote and are one of the distinguishing characteristics of the Itto-ryu lines; all but two include their use in training.

Mizoguchi-ha Itto-ryu

Mizoguchi-ha Itto-ryu technique is notable for its sayu tenka demi no hitachi, a set of five odachi and three kodachi techniques characterized by the use of very smooth and adroit movements to both the left and right sides of the opponent’s attack, followed by an immediate cutting or thrusting counter-movement. Zanshin (a state of intense awareness and concentration) is intense, starting with the initial movement of the exponents from toma (a “far-away” distance, generally about three to five paces away from one another) to kosa (literally “crossing,” with the swords crossing at the monouchi or “working area” of the blade, about 15 cm. from the tip).

At this point, uchidachi presses shidachi (the individual performing the “winning” side of the technique), forcing him to back up. Shidachi then re-establishes a measure of control and returns to the center of the training area. Uchidachi then attacks with either a cutting or thrusting movement and forces shidachi to evade the attack to either the left or right.

As uchidachi continues his attack, it is countered to one or another side. These techniques all demonstrate possible responses to both sides. It should be further noted that the odachi techniques have both omote (surface level) and ura (inner, more sophisticated level), and there are a number of variations, so the curriculum is actually larger than it appears at first glance.Shidachi in hasso no kamae. Is clasing on a stationary uchidachi. Who is standing in seigan no kamae.

What is particularly noticeable about Mizoguchi-ha Itto-ryu swordsman is the smoothness of their techniques. Their lack of vocalized kiai is also evident: the waza are silent, but the stark intensity as uchidachi and shidachi close is literally breathtaking. Also, unlike most kenjutsu schools, whose weapons make sounds as they contact one another, swords of Mizoguchi-ha Itto-ryu exponents make almost no sound at all. There is, nonetheless, a very strong sensation of the swords’ cutting and the attention paid to timing and to the line of the attack is beautiful in its severity. One gets a very distinct sense that there is no slack at all in their techniques and that facing a Mizoguchi- ha swordsman would have been a difficult thing, indeed.

Nakanishi-ha Itto-ryu

The basic Nakanishi-ha Itto-ryu kata are, at least superficially, essentially the same as those of its parent Ono-ha Itto-ryu. What differs are the more subtle aspects of timing, breathing, and use of distancing. Naturally, other interpretations and variations have developed over time, but the differences are quite subtle and require that one observe both schools over a period of several years to detect and understand how the two schools have diverged.

The general impression one receives viewing Nakanishi-ha Itto-ryu is of power and dignity. The stances are wide, the movement is deliberate. Even when techniques are done rapidly they seem slow, due to the intensity and gravity displayed by the exponents in their practice. As in Ono-ha Itto-ryu, the uchidachi wears onigote, the heavy gauntlets that allow them to receive full-power strikes to the wrists and forearms at the end of the kata.

Kogen Itto-ryu

There are twenty-five sword techniques in Kogen Itto-ryu and five naginata waza, which were introduced from the Toda-ha Buko-ryu. That may not seem like a very large technical repertoire, but the content of the techniques is so well conceived and executed that any more would be extraneous.

Although the iaijutsu techniques are no longer practiced, their names remain in the mokuroku and deserve mention, because of their unusual nature. Unlike any other ryu that I’ve seen, the iai techniques are referred to by the various kuji (literally, “nine characters,” derived from esoteric Buddhism, used by koryu in various ways to instill particular mental states that are useful in combat and in training). Each of the characters is associated with a particular Buddhist worthy, but detailed information about the techniques is not available. Most current members of the Kogen Itto-ryu are skilled exponents of Muso Shinden-ryu iaido and kendo, as well as the classical techniques; some also have backgrounds in jojutsu or other modern unarmed arts.

Kogen Itto-ryu technique is very spare, with an economy of movement and a very strict sense of “line” and “timing.” It has no superfluous content, although the meaning or utility of some movements is not immediately apparent. The reiho (formal etiquette) of the ryu is also fairly unique and seems to be a development of the mid-Edo period in that a tachiainin (observer) lays out the weapons and stays in attendance throughout the performance of techniques, a holdover from dueling etiquette.

Another holdover from the past is the presence of a number of Kogen Itto-ryu dojo throughout the area of what used to be called Musashi Province. Licensed instructors of the ryu taught in their own dojo and, over the years, different lines of teaching developed, leading to several minor differences in technique and even in curriculum. The headmaster of the ryu is still a member of the Henmi family and he continues to teach and train in the Yobukan Dojo; other people do the same in other parts of Saitama Prefecture. All, however, continue to maintain close contact with the Henmi family, “touching base with the source”; this has led to a remarkable vitality and a sense of camaraderie among the scattered students that will likely ensure that Kogen Itto-ryu will remain a vital part of their respective communities.

Hokushin Itto-ryu

Hokushin Itto-ryu was created late in the Tokugawa era; practice in the nineteenth century placed a heavy emphasis on shinai geiko, using the protective equipment and bamboo swords popularized by Nakanishi Tanetake, as well as the traditional kata. After more than two hundred fifty years of the enforced peace of Pax Tokugawa, and the subsequent lack of chances to apply their skills in combat, many members of the bushi class were no longer satisfied with practicing only kata. Moreover, the newly developed protective equipment made possible a type of vigorous training (known as ji geiko in modern kendo) that was attractive to young men of the period and helped the Hokushin Itto-ryu (and other schools that also placed an emphasis on this kind of study) gain many members.

When modern kendo was formally established during the mid-Meiji period (1868–1912), and its technical curriculum was being formed, several members of the committee responsible for this work were senior exponents of the Hokushin Itto-ryu. Because of their level of skill in this kind of freestyle practice, they exerted a great influence on both the techniques and training methods of modern Japanese kendo.

Hokushin Itto-ryu technique is predicated on the ability to continually press the opponent and, no matter how he tries to attack, to be able to “ride” his sword, cutting through and knocking it down in the kiriotoshi action, and especially to strike at the very instant the enemy attempts to attack.

The techniques are relatively simple in appearance, rather like those of Kogen Itto-ryu in that sense, with no waste or flashy movement. The uchidachi wears the same sort of onigote that are used in Ono-ha and Nakanishi-ha Itto-ryu kata. The stances appear to be slightly more erect than in other Itto-ryu systems, but the finishing techniques are delivered with the same feeling of weight and power. Indeed, the “gravity” of Hokushin Itto-ryu technique is striking and leaves a very strong impression, a sort of “after-image,” on those who see it.

Itto Shoden Muto-ryu

Muto-ryu kata resemble, not surprisingly, those of its two parent Itto-ryu styles (Ono-ha and Nakanishi-ha), with what appears to be an admixture of elements from Jikishinkage-ryu, which Yamaoka is also said to have studied. There are over fifty techniques in the ryu’s curriculum, similar to Itto-ryu in general, but done with a slightly different “flavor” than in either Ono-ha or Nakanishi-ha. As in those schools, the uchidachi wears the onigote; the bokuto (wooden swords) used are fairly straight and heavy. An unusual feature of some Itto Shoden Muto-ryu kata is the stance taken on one leg, which comes from Jikishinkage-ryu

Conclusion

All of the koryu kenjutsu ryu include distinctive, effective techniques that were developed and refined over generations and through the efforts of many extraordinary men. Though several classical systems of swordsmanship extant today are older than the various schools of the Itto-ryu tradition, Itto-ryu is considered one of the most truly representative forms of Japanese swordsmanship, due to its sophisticated theory and training methods and its influence on modern kendo, the Way of the Sword.

The “apparent” simplicity of Itto-ryu, relying as it does on “one technique [which becomes] ten thousand techniques,” in accord with the most fundamental principles of combat, has provided a firm technical base. This template enables students of both classical and modern swordsmanship to learn and study the art in all its aspects. It is in large part due to the dedication and determination of past and present exponents of the Itto-ryu that this transmission has been maintained, and it is a debt that modern exponents must always keep in mind as they guide their ryu into this new millennium.

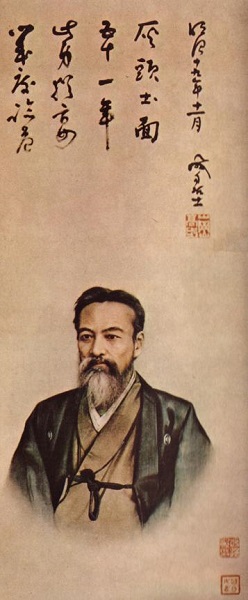

Portrait of Yamaoka Tesshū (1886)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yamaoka_Tessh%C5%AB

http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yamaoka_Tessh%C5%AB

http://www.japansociety.org.uk/8232/%E5%89%A3%E7%A6%85%E6%9B%B8%E3%80%80ken-zen-sho-the-zen-calligraphy-and-painting-of-yamaoka-tesshu/http://www.theway.jp/zen/teshhu_shinkan.html

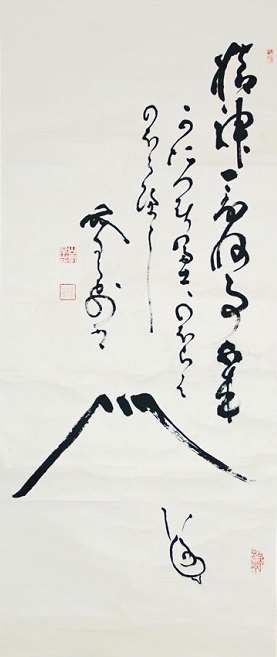

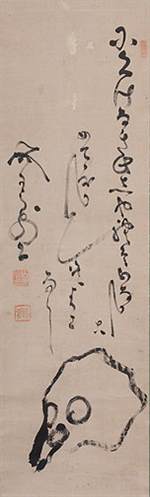

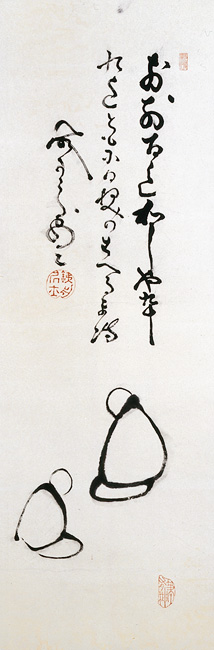

Fuji & Snail by Tesshū

Painting of snail climbing up to Mt. Fuji. Do your best. Keep trying and you'll find a way out.

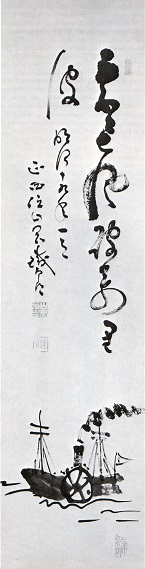

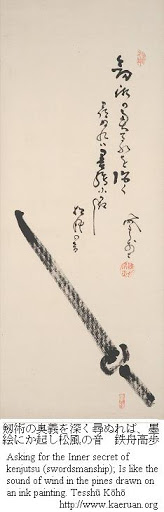

Zen Steamboat by Tesshū

"Rides the great winds, shattering the waves of ten thousands leagues."

Hitsuzen-kai Collection

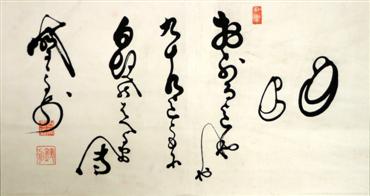

Zen Skull & Ikkyu's Poem by Tesshū

"Don't be scared

Of this weather beaten

Abandoned old skull;

It is a matter of congratulation

Better than any other!"

(Nikugenaki kono share [koube] anakashiko

medetakaku kashiku kore yori wa nashi)

On New Year's Day, the famous Zen master Ikkyu walked around the town brandishing a human skull while shouting, "Beware, beware!"

When asked why he would do such a thing on a day of celebration, Ikkyu recited the above Zen verse. If there is death there must have been life.

That is a matter of congratulation; but since life will end as death, don't waste your time on frivolous pursuits.

In short, "Live completely, die completely!", Tesshu's motto.

Daruma by Tesshū

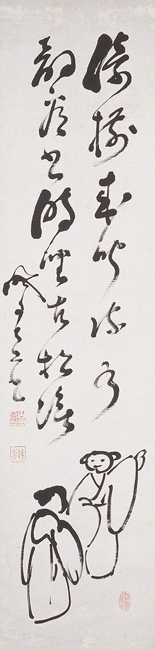

Kanzan Jittoku by Tesshū

Hanging scroll, ink on paper

133.9 x 32.9 cm

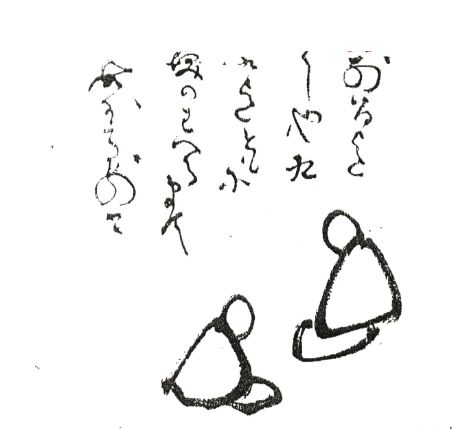

高砂 Takasago by Tesshū

Zen Couple

Hanging scroll, ink on paper

104.2 x 34.9 cm

"This is a wonderful interpretation of Takasago,

a No play about an old couple. The pair lived for

decades in connubial bliss, and died at a great

old age. With just a few masterful brushstrokes,

Tesshu has created two elderly lovers who sit in

quiet contentment together. The husband offers to

go first, but the couple, as close in death as in

life, will likely pass away within a few days of

each other. The kind of Zenga served as good luck

charm for married couples. The particular style

of depicting Takasago appears to have originated

with Tesshu and thereafter become a standard

theme in Zenga." A lay Zen master, Tesshu

received his certificate from Tekisui of Tenryuji.

Also a master swordsman, he founded the

Muto (No-sword) School and was a tireless

promoter of the "Zen and the sword are one" philosophy.

The poem reads:

「お前百まで わしゃ九十九まで 共に白髪が抜けるまで」

"You'll reach one hundred,

I'll reach ninety-nine,

as our hair turns white together"

(Translation: John Stevens, 2001)

bronze statue of Tesshu which stands at Tesshu-ji temple in Shizuoka city

bronze statue of Tesshu which stands at Tesshu-ji temple in Shizuoka city

101 Zen Stories

Transcribed by Nyogen Senzaki (千崎如幻 1876–1958) & Paul Reps (1895-1990)

Philadelphia, David McKay Company, 1940. 126 p.

is a 1919 compilation of Zen koans including 19th and early 20th century anecdotes compiled by Nyogen Senzaki, and a translation of Shaseki shū, written in the 13th century by Japanese Zen master Mujū (無住) (literally, "non-dweller"). The book was reprinted by Paul Reps as part of Zen Flesh, Zen Bones.

66. Children of His Majesty

Yamaoka Tesshu was a tutor of the emperor. He was also a master of fencing and a profound student of Zen.

His home was the abode of vagabonds. He has but one suit of clothes, for they kept him always poor.

The emperor, observing how worn his garments were, gave Yamaoka some money to buy new ones. The next time Yamaoka appeared he wore the same old outfit.

"What became of the new clothes, Yamaoka?" asked the emperor.

"I provided clothes for the children of Your Majesty," explained Yamaoka.

82. Nothing Exists

Yamaoka Tesshu, as a young student of Zen, visited one master after another. He called upon Dokuon of Shokoku.

Desiring to show his attainment, he said: "The mind, Buddha, and sentient beings, after all, do not exist. The true nature of phenomena is emptiness. There is no realization, no delusion, no sage, no mediocrity. There is no giving and nothing to be received."

Dokuon, who was smoking quietly, said nothing. Suddenly he whacked Yamaoka with his bamboo pipe. This made the youth quite angry.

"If nothing exists," inquired Dokuon, "where did this anger come from?"

93. Storyteller's Zen

Encho was a famous storyteller. His tales of love stirred the hearts of his listeners. When he narrated a story of war, it was as if the listeners themselves were in the field of battle.

One day Encho met Yamaoka Tesshu, a layman who had almost embraced masterhood of Zen. "I understand," said Yamaoka, "you ar the best storyteller in out land and that you make people cry or laugh at will. Tell me my favorite story of the Peach Boy. When I was a little tot I used to sleep beside my mother, and she often related this legend. In the middle of the story I would fall asleep. Tell it to me just as my mother did."

Encho dared not attempt this. He requested time to study. Several months later he went to Yamaoka and said: "Please give me the opportunity to tell you the story."

"Some other day," answered Yamaoka.

Encho was keenly disappointed. He studied further and tried again. Yamaoka rejected him many times. When Encho would start to talk Yamaoka would stop him, saying: "You are not yet like my mother."

It took Encho five years to be able to tell Yamaoka the legend as his mother had told it to him.

In this way, Yamaoka imparted Zen to Encho.

Haiku by Tesshū

腹痛や

苦しき中に

あけからす

fukutsu ya

kurushiki naka ni

akekarasu

Tightening my abdomen

Against the pain.

The caw of a morning crow.According to Neal Dunnigan, in his book "Zen Stories of the Samurai" (Lulu Enterprises, Inc., North Carolina, 2005), the above-quoted haiku was Tesshu's death poem (辞世の句 jisei no ku).

"Yamaoka Tesshū (1836-1888), a swordsman and a lay

teacher of Zen, wrote the following poem on the verge of death.

Whereas the poems quoted up to now have all been in Chinese

and written by monks, Tesshū's verse is in Japanese, in haiku form.

Stomach swollen,

and in the midst of this pain,

the crows at dawn

It is said that Tesshū's disciples expressed considerable disappoint-

ment that their teacher in his final hours was not able to rise

above the level of his physical discomfort, until it was pointed out

to them that Zen does not teach one how to rise above the world,

but how to live in it."

Zen Poetry by Burton Watson, in: Zen: Tradition and Transition, Grove Press, New York, 1988, p. 112.

Tessú: Búcsúverse

görcsbe rándult has

—

múljon el a kín

— varjú

károg

— már pirkad —

(Terebess Gábor fordítása)

A fájdalom ellen

megfeszítem hasamat —

varjú károgása hajnalban.

(Tóth Andrea fordítása)

Jamaoka Tessu kiemelkedő alakja volt annak a viharos időszaknak, amelyben egy új Japán született. A közéletben Tessu Szaigo Takamorival tárgyalt, és előkészítette a sógunátus utáni békés hatalomváltást. Az Út egyéni követőjeként negyvenöt évesen mély megvilágosodást ért el, és felismerte a kardforgatás, a zen és a kalligráfia belső alapelveit. Ettől fogva Tessu olyan volt, mint Mijamoto Muszasi: "...úgy telik az életem, hogy nem egy meghatározott Utat követek." (Az öt elem könyve) Tessu is kiemelkedően sokoldalú és termékeny mesterré vált: egyedülálló kardforgató, aki a Kardnélküli Iskolát megalapította; a Tekiszui hagyomány szerinti bölcs és könyörületes zen tanító; páratlan kalligráfus, aki ecsetével fejezte ki az ég és a föld összes tanítását. Még ma is, több mint egy évszázaddal a halála után, ecsettel készült műveiben érzékelhetjük Tessu hihetetlen életerejét. Ha helyesen értelmezzük kalligráfiáit, teljesen szembetűnő az a nagy átváltozás, ami Tessu megvilágosodásával együtt járt és az az egyre mélyülő éleslátás, ami életének utolsó nyolc évében tapasztalható.

Hús-vér zen

összeáll. Paul Reps; [ford. Acsai Roland ]. Cephalion, Szentendre, 2006, 136 oldal

66. ŐFELSÉGE GYERMEKEI

Yamaoka Teshu a császár tanára volt. Mestere volt a vívásnak

és a zennek.

A vándorok szállásán lakott és csak egy öltözet ruhája

volt. Úgy festett, mint egy hajléktalan.

Egyik nap szemet szúrt az uralkodónak tanára szegényes

öltözete, és adott neki valamennyi pénzt, hogy új ruhákat

vegyen. Yamaoka el is fogadta.

Ám amikor legközelebb találkoztak, Yamaoka ugyanabban

a ruhában volt.

A császár megkérdezte tőle, mit csinált a pénzzel.

Yamaoka így válaszolt:

- Ruhákat vettem belőle fenséged gyermekeinek.

82. SEMMI SEM LÉTEZIK

Yamaoka Teshu, egy fiatal zen tanítvány sorra látogatta a

mestereket. Egy nap Dokuonhoz érkezett.

Meg akarta csillogtatni okosságát és így szólt:

- Az elme Buddha, és a dolgok végül is nem léteznek.

Az igazi valóság az üresség. Nincs csalódás, sem bölcsesség,

sem középszer.

Dokuon csendesen pipázgatott, egyszer csak rácsapott

pipájával a tanítványra.

A tanítvány dühbe gurult.

- Ha semmi sem létezik, mi váltotta ki a dühödet? -

kérdezte a mester.

93. A MESE

Encho nagy mesélő volt. Amikor szerelmes történetet mondott,

a szivek égni kezdtek, amikor háborús történetet, minden

izom megfeszült.

Egy nap Encho találkozott Yamaokával, aki egy laikus

volt, de nagy zen szakértő.

Yamaoka arra kérte, hogy mesélje el neki a barack fiú

legendáját, amelyet gyerekkorában mindig az anyja mesélt

neki, mielőtt elaludt.

- Hadd készüljek fel! - kérte Encho.

Pár hónappal később Encho ismét megjelent Yamaokánál.

- Felkészültem, elmondom a mesét.

- Talán nem eléggé készültél fel... - felelt Yamaoka a

csalódott Enchónak.

Encho újra és újra megpróbálkozott a történet elmondásával,

de mindig ugyanazt a választ kapta:

- Még nem vagy olyan, mint az anyám.

Öt év telt el így, míg végre Encho elmondhatta a mesét.

Így adta át Yamaoka a zent Enchónak.