ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

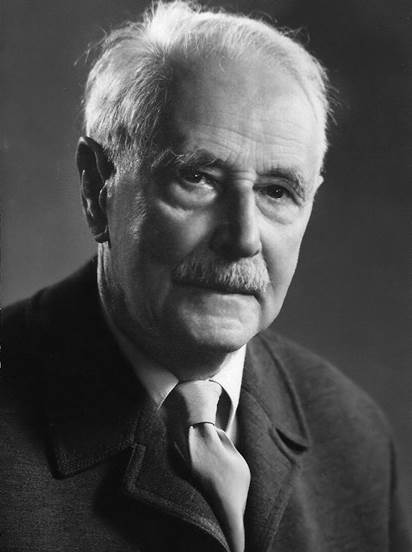

Walter Liebenthal (1886-1982)

Chinese name: 李華德

Walter Liebenthal online

http://buddhism.lib.ntu.edu.tw/DLMBS/en/author/authorinfo.jsp?ID=1165

![]()

竺道生 Zhu Daosheng (335/355-424/434)

PDF: Walter Liebenthal: Chao Lun, The Treatises of Seng-chao

Hong Kong, Hong Kong University Press. 1968."The "Chao Lun: The Treatises of Seng-Chao", is the main scripture of the first period of Chinese Buddhism (about A.D. 300-700) before Dhyana-Buddhism absorbed all other interests (A.D. 700-1100). The Author believes that the two periods are connected and that in Dhyana-Buddhism the earlier thinking emerged cleansed from the traces of its Indian origin. Seng-Chao interpreted Mahayana, Hui-Neng and Shien-Hui re-thought it. The position of the Author is unusual and might be contested. But after a life-time given to the study of Chinese-Buddhism and the Chao-Lun in particular he has the right to be heard."

(Introduction to 2nd Edition by Hong Kong University Press - 1968)

PDF: Walter Liebenthal: A Biography of Chu Tao-Sheng

Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 11, No. 3 (Oct., 1955), pp. 284-316.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/2382916.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A239b14ee26681d7db124c983faed3d131. Tao-sheng's Youth -His Sojourn on Lu-shan 284

2. Discussion on Lu-shan 289

3. Tao-sheng in Ch'ang-an 290

4. Life in Chien-k'ang 293

5. The Shadow of Lu-shan 298

6. Hsieh Ling-yun 301

7. The Arrival of the Nirvana Siutra and the Icchantika Conflict 303

8. Tao-sheng's Las t Years 308

9. Tao-sheng's Influence 309

The Writings of Tao-sheng 312

A. Commentaries. 312

B. Pamphlets. 313

C. Correspondence. 315

PDF: Walter Liebenthal: The World Conception of Chu Tao-sheng (I)

Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 12, No. 1-2 (1956), pp. 65-1031. The Sage Is Cosmic Order 65

2. The Indian and the Chinese Buddha 67

3. Buddha's Response-Kan-ying and San-shih 69

4. Tao-sheng's Concept of Kan-ying 73

5. The Body of Response 76

6. The Response of the Buddha Is Conditioned 77

7. The Way and the Goal 80

8. Becoming a Buddha 81

9. (True) Piety Requires No (Mundane) Reward (Writings B1) 84

10. The Dharmakiya Is Bodyless (Writings B5) 85

11. The Buddha Is Not Found in a Paradise (Writings B6) 86

12. Instantaneous Illumination (Writings B2) 86

13. Buddha Nature 91

14. Buddha Nature Will Be Realized in the Future (Writings B2) 93

15. The Shrine of the Tathagata 93

16. The lechantika (Writings B8) 95

17. Tao-sheng's Belief in Revelation 97

18. Tao-sheng's Meditation 99

19. Conclusions 100

PDF: Walter Liebenthal: The World Conception of Chu Tao-sheng (II)

Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 12, No. 3-4 (1956.10), pp. 241-2681. The Buddha 241

2. Cosmic Order (u) 243

3. The Middle Path 245

4. The goal 246

5. Buddha's response 248

6. The response of the Buddha is conditioned 250

7. Buddha nature 251

8. Buddha nature will be realized in the future 251

9. Soul and Self 251

10. The icchantika 252

11. The Shrine of the Tathaigata 252

12. The dharmakaya is bodyless 253

13. The Buddha is not found in a paradise 254

14. Instantaneous Illumination 255

15. Karma 262

16. (True) piety requires no (mundane) reward 265

17. Tao-sheng's belief in revelation 266

18. Tao-sheng's meditation 268

Walter Liebenthal (1886-1982)

荷澤神會 Heze Shenhui (670-762)

PDF: “The Sermon of Shen-hui,”

Translated by Walter Liebenthal

Asia Major, New Series, III (1953), part II, pp. 132-55.

永嘉玄覚 Yongjia Xuanjue (665–713), aka 永嘉大师 Yongjia Dashi

證道歌 Zhengdao ge

PDF: "Yung-Chia's Song of Experiencing the Tao"

Translated by Walter Liebenthal

Monumenta Serica, VI (1941), 1-39.Professor Liebenthal has given here, in addition to the translation of the text, a scholarly introduction, in which he discusses the authorship, the author, and the text; Appendix I and II, in which he lists textual variants; and Appendix III, in which he translates pertinent biographical material from the Sung kao-seng chuan (Japanese, So koso den), Taisho No. 2061 (Vol. L, pp. 709-900) and the Ching-te ch'uan-teng lu 景德傳燈錄 (Japanese, Keitoku dento roku), Taisho No. 2076 (Vol. LI, pp. 196-467). Perhaps the Zennist will not always agree with the author's translation of terms or with his highly personal interpretation of the text. (Robert Payne)

![]()

Ch'an-tsung Wu-men kuan: Zutritt nur durch die Wand / Wu-men Hui-k'ai

übersetzt und mit Einleitung und Anmerkungen versehen von Walter Liebenthal.

Heidelberg : L. Schneider, 1977. 142 p.

A 91 esztendős sinológus és indológus professzornak az elegáns kiadású könyvecskéje a Zen-buddhizmus híres alapkönyvének nem az első német fordítása. (Az elsőség Heinrich Dumoulin-é, akinek fordítása még Pekingben jelent meg 1943-ban, majd Tokióban utánnyomásban s végül javított kiadásban 1975-ben Mainzban.) De a Wu-men kuan, mint minden nagy klasszikus, megérdemli a többszörös fordítást és kommentárt. Még inkább indokolt ez a többszörös tolmácsolás a Zen-szövegek esetében, hiszen köztudott, hogy ezeknek per definitionem nem is lehet egyetlen értelmük. Liebenthal fordításának a törekvését jelképesen summázza a cím fordításának a tradíciótól eltérő megoldása: az általában „Átjáró kapu nélkül" (Pass ohne Tor, pl. Dumoulin-nél) Címen visszaadott Zen-gondolat valóban eltorzul ebben a formában: az átjáró „szoros" vagy „hágó" képzetet asszociál s a kapunélküliség csak az építészeti tartozék, a fából ácsolt „kapu" vagy „ajtó" hiányát sugallja - holott a valódi értelem éppen az, amit Liebenthal címfordítása kényszerít az olvasóra, vagyis: „itt át kell hatolnod, de kapu nem lévén, fejjel a falnak!" A Zen értelmében: nem az egyenes, nem a járt úton, hanem valami „falrengető" vagy „faljáró" meg-oldással, trükkel vagy varázslattal, akár pedig transzcendens - eszmei - megoldással. Liebenthal német fordítása azonban önmagában hordja korlátját is: korszerű németesítés ez, de éppen kényszerítő egyértelműsége az, ami szemben áll a Zen poétikus és polivalens szövegeivel. Korrekt és körültekintő kommentárjai enyhítik szövegfordításának ezt a merevségét - látszik rajtuk az a másfél évtized, amit Pekingben és Kunmingban, valamint kínai buddhista kolostorokban töltött 1935-től szankszkrit professzorként és Zen noviciusként. Végül is azt kell mondanunk, hogy a 48 híres, 13. századi gyűjtésű Zen-anekdota újabb német fordítása értékes gazdagítása a mostanában sok divatos fércművel elárasztott Zen-irodalomnak: hiteles szöveg hiteles tolmácsolása, filológiai apparátussal és névjegyzékkel, s méltóképp sorakozik elődei és kortársai mellé (Demiéville Lin-chi fordítása vagy Gundert Pi-yen lu tolmácsolása mellé). Mindenképp megérdemli, hogy a Zen iránt felébredő hazai érdeklődés számon tartsa és felhasználja.

Miklós Pál (Helikon, 1978/1-2. sz., 250. old.)