ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

石霜慶諸 Shishuang Qingzhu (807-888)

Shishuang Qingzhu or Qingju 石霜慶諸 (Shih-shuang Ch'ing-chu, Sekiso Keisho), 807-888. Not to be confused with Ciming (Shishuang) Quyuan. A Dharma-heir of Daowu Yuanzhi, in the line of Yaoshan Weiyan. He practiced as rice steward under Guishan before studying with Daowu. Dongshan Liangjie had a monk track him down and he was appointed abbot on Mount Shishuang. His community there was noted for never laying down to sleep and was called the "Dead Tree Hall." He appears in Records of Serenity 68, 89, 96, 98. He appears in the Sayings and Doings of Dongshan (Dongshan yulu) section 75. See Dogen's Gyoji.

15.367 Chan Master Tanzhou Shishuang Qingzhu (Sekiso Keiso)

in: Records of the Transmission of the Lamp: Volume 4: The Shitou Line. (Books 14-17),

Translated by Randolph S. Whitfield,

Kindle Edition, 2017

Chan master Qingzhu of Shishuang Shan in Tanzhou (Hunan, Changsha) was a native of Luling Xingan (Jiangxi, Xingan) whose family name was Chen. At the age of thirteen he had his head shaved under the guidance of Chan master Shaoluan at Xishan in Hongjiang (Jiangxi, Nanchang) and at the age of twenty-three received the full precepts at Mount Songyue. At Luoyang (Henan) he applied himself to studying the teachings of the Vinaya. Although following the Vinaya rules he increasingly inclined to the Chan school. Going to Dagui Shan (Lingyou’s) Dharma-community, he became the head of the rice-hulling shed.

One day the master was in the rice-hulling shed sieving rice. Guishan said to him, ‘Alms is the giver and the things given, do not throw it about.’

‘It is not being thrown about,’ replied the master.

Guishan picked up a grain from the ground and said, ‘You say that it is not being thrown about, so how did this get here?’ The master had no reply. Guishan continued, ‘If this grain of rice is not wasted a hundred thousand will be born from it.’

‘Something is not yet clear,’ said the master. ‘A hundred thousand grains arising from this single grain, but where did this single one arise from?’

Guishan laughed and returned to the abbot’s quarters. During the evening meeting he ascended the hall and said, ‘Oh, great assembly! There is a worm in the rice!’*

The master later went to visit Daowu and asked him, ‘What is the bodhi that strikes the eyes?’

Daowu summoned a monk, the monk answered, ‘yes’ and Wu said to him, ‘Add some clean water to the pitcher.’ Then he asked the master, ‘What was your question just now?’ The master was just about to repeat the question, whereupon Daowu got up and left. From this the master was awakened.

Daowu asked, ‘If I would develop an illness and should want to leave the world because there was something in the heart causing pain, who could remove it?’

‘Both the heart and the something do not exist, so the act of removing it is only to pain’s profit.’

‘Excellent! Excellent!’ said Daowu.

From this time on the master was counted as one of the senior monks.Later, as a result of the master having withdrawn from contact with the world, he started mixing with the workers in the ceramics district, wandering off early in the mornings and returning at night. People couldn’t understand [what was going on]. Later Dongshan [Liangjie] sent a monk to investigate and then the matter came to light by being brought to the attention of the incumbent of Mount Shishuang. (i. e. Daowu).

Then, when Daowu was about to submit to the generations and leave the world, with the master [now installed] as Dharma-heir, Qingzhu (the master) himself went to attend at Shishuang Shan [on Daowu], caring daily for him with diligence. After returning to quiescence [Daowu’s] students gathered like clouds around the master [Qingzhu], more than five hundred in number.

*

One day the master said to the assembly, ‘A teaching which is merely for this one period, binds the present generation hand and foot. All seems reasonable, yet all sinks into the present, right up to the Dharma-body which is not a body. Just this is the highest level of the teachings. The śrama as of my generation are all on a disagreeable way. If there are differences they fall out, if not they sit in the mud [together] and only hear, see and talk from a deluded heart.’

A monk asked, ‘What is the meaning of the coming from the West?’

‘A lump of rock in the emptiness,’ replied the master. The monk bowed.

‘Understood?’ asked the master.

‘Don’t follow you,’ replied the monk.

‘Were it understood, it would have been a hit on your head,’ said the master.

*

Question: ‘What is the venerable’s proper business?’

‘Is Shitou still sweating?’ replied the master.

‘Having come here, why is it still not possible to get an answer?’

‘The mouth is under the feet,’ said the master.Question: ‘Is the real body still capable of manifesting in the world or not?’

‘Not capable of manifesting in the world,’ said the master.

‘Nevertheless, what about the true body?’

‘The [narrow] mouth of a translucent porcelain bottle,’ replied the master.The master was in the abbot’s quarters when a monk outside his window asked, ‘Although so near, why is it not possible to look on the master’s visage?’

‘My words have never been hidden anywhere in the world,’ replied the master.

The monk brought this up with Xuefeng, ‘Never been hidden anywhere in the world – what is the meaning of this?’

‘Is there anywhere from which [Ven.] Shishuang is absent?’

The monk returned to the master and brought Xuefeng’s words up with him. The master said, ‘That great old boy, is there such a one who can die quickly!’(Textual comment: Chan master Dongchan Qi said, ‘Just suppose – is it that Xuefeng understood Shishuang’s meaning or did he not understand the meaning? If understood, why does he talk about dying quickly? If not understood, what is that about? As for Xuefeng, is it possible that he did not understand? It seems that although there are no differences in the Buddha-dharma, still masters’ endowments do differ so that in liberation there are differences too. Shishuang told him, “Never been hidden anywhere in the world.” It is necessary to practise, to begin to obtain such an understanding, then obfuscation is no longer possible.’)

Yungai [Zhiyuan, 16.399] asked, ‘When all the doors of the ten thousand families are closed, there is no questioning; but what of the time when doors of the ten thousand households are all open?’

‘What is going on in the meditation hall?’ replied the master.

‘There is no one who takes it to heart,’ said the monk.

‘Talking, even to the brink of death, is merely a small part of it,’ said the master.

‘Not yet understood – what is the venerable saying?’

‘There is not anyone who takes it to heart,’ said the master.(Textual comment: Dongchan Qi said, ‘Now, is Shishuang’s meaning similar? If it is said that it contains something of former times, then why is it not permitted? If it is said that it contains a different principle, then again it is just a kind of universal way of talking. Moreover, what was the principle the ancients talked about?’)

Question: ‘Buddha-nature is like empty space – how so?’

‘When lying down it is, when sitting up it is not,’ replied the master.

‘What about forgetting to bring one foot forward when walking?’

‘Not [eating] from the same plate with you,’ replied the master.

‘When the wind gives rise to waves, what then?’ asked the monk.

‘In the capital of Hunan there are noisy quarrels. There are those who are not willing to cross the Jiangxi [River],’ replied the master.

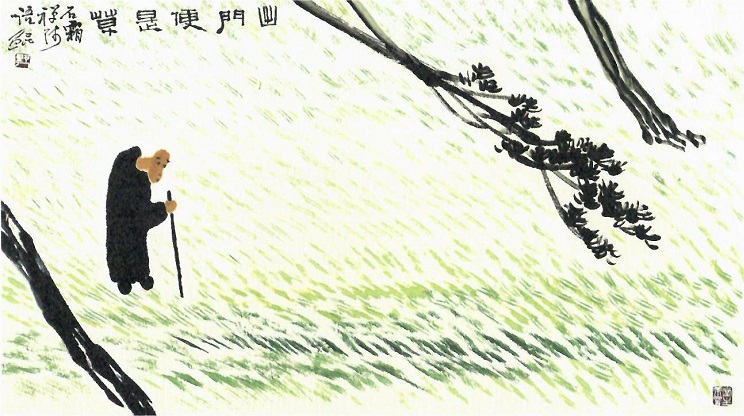

Illustration by 李蕭錕 Li Xiaokun (1949-)Because a monk recommended Dongshan to take part in the community, Dongshan showed himself and said, ‘Elder brother! Autumn is beginning, the summer [retreat] is coming to an end, so the monks will be leaving, going east and west. The only necessary thing is, that even when journeying for ten thousand li through places where there is not even a tuft of grass, just to be able to do that.’ Dongshan also said, ‘If it is only ten thousand li without a tuft of grass, then how to accomplish that?’

The master heard of this and said, ‘Outside of the gate – just there is the grass.’

The monk brought this up with Dongshan who said, ‘How many people is it possible to accommodate within the empire of the Great Tang?’(Textual comment: Chan master Dongchan Qi said, ‘Just say, did Shishuang understand Dongshan or not? If it is said that he understood, this is merely going round and round with the times that all monks do every day; welcoming what comes and seeing off what goes. This is tantamount to losing the road and grazing sideways in the grass. Is this smoothly following the wagon trail? If it is said that Shishuang did not understand, then how is Dongshan’s meaning to be interpreted? Given such [clever ones] as these, is there still something to understand? And where do these monks go? If you can be clear about this, then it is possible to say whether it is still just a little village song not yet seen into, but one can also say about the above written words: “Like this it doesn’t go.” ’)

During the twenty years that the master spent with Shishuang, there were disciples who sat in meditation without lying down and those who stood upright stock still like tree stumps and these were called ‘the withered tree crowd’.

Emperor Xizong (r.874-888 CE) heard of the master’s reputation in practis-ing the Way. He dispatched an envoy carrying an offer of purple robes to the master, but the master firmly refused to accept them.

On the 20th day (thirty-sixth year of the sexagenarian cycle) of the 2 nd month in the 4th year of the reign period Guangqi, corresponding to the forty-fifth year of the sexagenarian cycle, signs of illness announcing the master’s quiescence showed themselves. Eighty-two years of age, he had been a monk for fifty-nine years. On the 15th day of the 4th month he was buried in the north-west corner of the courtyard. The posthumous title of ‘Great Master of Universal Understanding’ was conferred upon him by imperial decree and his pagoda was ‘Seeing the Signs’.