ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

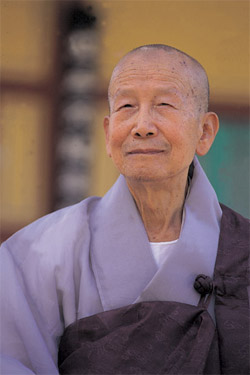

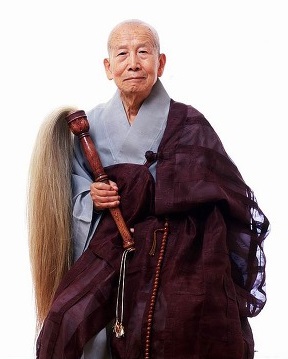

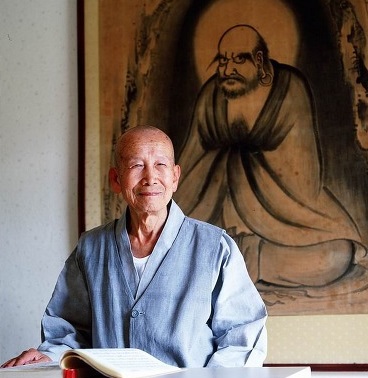

서옹상순 / 西翁尙純 Seo-ong Sangsun (1912-2003)

(Magyar átírás:) Szoong Szangszun

Seo-ong Sangsun (1912 ~ 2003)

http://www.koreanbuddhism.net/master/priest_view.asp?cat_seq=10&priest_seq=7&page=2

Regarded as “Korea's Linji,” Master Seo-ong devoted his life's work to advocating the “True Person” (chamsaram) religious movement.

Career

Master Seo-ong was born into the house of a Confucian scholar as an only son on October 10, 1912, in Nonsan, Chungcheongnam-do Province. At the age of 6, he lost his father, and then ten years later, in 1928, while attending Yangjeong, one of Seoul's most prestigious high schools, he received word of his mother's passing. With her death, he keenly felt life's impermanence and from this point forward he harbored a great sense of doubt about life. During the Japanese colonial occupation, worried about the days to come facing his pitiable homeland, he happened to read Gandhi's autobiography and developed a deep connection with Buddhism. During that time, he heard a sermon given by the head of Buddhist propagation, the Venerable Daeeun, and gradually he came to the decision that he would be ordained. In 1932, he graduated from Yangjeong High School and entered the Central Buddhist College (the present day Dongguk University). Even after his entrance into college, he remained at some remove from his peers, and his desire to become a monk did not diminish. Thus, that year he was introduced by Master Daeeun to Master Manam at Baekyangsa Monastery under whose direction he was ordained.

At the age of 23, in 1935, Master Seo-ong, after graduating from the Central Buddhist College, worked at Baekyangsa as a lecturer in English. Then, in 1937, he spent two years as a student of Master Hanam at Cheongnyang Meditation Hall (Seonwon) in Mt. Odaesan, absorbed in the study of Seon meditation. There he met a student who was studying in Kyoto, Japan, at Rinzai University (present day Hanazono University) and his urge to study abroad intensified. Finally, in 1939 at the age of 28, he enrolled at Rinzai University and spent his days studying and his nights practicing Zen meditation at the Rinzai sect's Myoushin-ji Temple. In addition, he also developed an intimate friendship with Professor Hisamatsu Shinichi, one of the world's leading authorities on Zen philosophy. In 1941, he graduated from Rinzai University and in his doctoral thesis True Self, he pointed out the errors in the Zen theory of the Japanese Buddhist scholars Nishita Kitaro and Tanabe Hajime. As a result, his work became part of the curriculum at Rinzai University and he received unstinting praise from the Japanese intelligentsia.

Following his graduation from Rinzai University, Master Seo-ong participated in a three-year meditation retreat at Myoushin-ji and then in 1944 he returned to Korea and began serious Seon meditation practice. He entered into meditation together with the esteemed Master Hyanggok, and in particular, while training in Anjeongsa Monastery in Tongyeong together with Master Seongcheol, his study saw immense progress. Following this, for the next twenty years he gave his undivided attention to his practice, training at many Meditation Halls across the country.

In 1962, at the age of 50, he became the first Seon Master of the newly opened University Meditation Hall at Dongguk University. Then, in 1964, after becoming the first Master of the Mumungwan (a meditation hall where one only engages in Seon practice and is not allowed to leave the temple) at Cheonchuksa, he served as head Seon master at the meditation halls of various other temples, including Donghwasa, Baekyangsa and Bongamsa. In 1974, at the age of 63, he served as the 5th Supreme Patriarch of the Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism and that same year he received and honorary doctorate degree from the University of Peradeniya in Sri Lanka. In 1978, even after retiring from his position as Patriarch, he served as Master of various meditation halls. In 1996, he restored the Gobul Chongnim(Monastic Compound) headquartered at Baekyangsa that had gone defunct during the Japanese colonial period, assuming the position of head Seon master and continuously instructing numerous disciples.

In 1998 and 2000, under the leadership of Master Seo-ong, the 1st and 2nd Open Seon Assembly were held at Baekyangsa of the Gobul Chongnim, dedicated to reaffirming Korea's Patriarchal Seon tradition. An “Open Seon Assembly” (muchaseonhoe) is a meeting where all people from all walks of life, whether monks or common people, men or women, old or young, noble or base, are equally allowed access to hear dharma sermons and engage in dialogue with the Masters. In doing this, Master Seo-ong had revived a practice that had been interrupted for over one hundred years.

On December 12, 2003, Master Seo-ong, who had expanded his Imje Seon inspired “True Person” movement throughout the nation, gathered the abbot and monks of Baekyangsa and said “I have to go now.” Assuming the same jwatal immang (dying while is a seated meditation pose) position as his Master Manam, he then passed into nirvana.

Zen Master Ven. Seo-ong Enters Nirvava

The Seoul Times, Tuesday, December 16, 2014

http://theseoultimes.com/ST/?url=/ST/db/read.php?idx=172

Writings

Master Seo-ong's literary output includes the Imjerok Yeonui (Commentary on the Records of Linji)(1974), Jeoldae Hyeonjaeui Chamsaram (The True Person of the Absolute Present) (1988), Seo-ong Seonsa Beopeojip vol. I and II (The Dharma Talks of Seon Master Seo-ong) (1998), and others. In particular, after the publishing of the Imjerok Yeonui, Linji Seon thought became the basis of the Korean Seon school, set upon the foundation of the Patriarchal Seon tradition.

Doctrinal Distinction

Whenever Master Seo-ong's name is spoken, it is always accompanied by a mention of the “True Person.” While he studied abroad in Japan, Master Seo-ong studied the Linji Lu, a text by Linji Yixuan, the founder of the Chinese Linji Chan sect. His mind was captivated in the phrase, muwi jinin (An Authentic Person of No Status) and he took this phrase on as his lifelong hwadu. What is meant by muwi jinin is that such dichotomies as sacred and profane, delusion and awakening, noble and base, and time and space are all transcended by the true self, with which nothing remains unconnected.

Master Seo-ong saw this “true self” as a state of non-discrimination and it was this concept that served as the focus of the muwi jinin idea of Linji. It is the awakening to the origin of this “true person” that is itself the “True Person.” With no thing newly awakened to, this is the original being of a genuine human. Master Seo-ong also saw that the “true person” originally is without distinctions between life and death, man and woman, young and old, good and evil, sentient beings and Buddhas, the universe, time and space. The “True Person” movement advocated by the Master was his way of taking a step beyond the thinking of muwi jinin.

“The seat of a 'true person' refers to a stage in which time, space, and even the unconscious is transcended. However, it is not something that lies outside of precisely this space of the dialogue that we now share. The shortcut that leads to this 'true person' is exactly Patriarchal Seon.”

The master went on to define the essence of Patriarchal Seon: “this is the search for the true likeness of the perfectly free human being, permeating the conscious and unconscious, permeating the totality as a perfect interfusion without obstruction.”

Within Master Seo-ong's practice methods of as well, Seon meditation was placed at the pinnacle, and he emphasized that Seon was always a “practice aimed at the awakening to our true countenance of intrinsic compassion.” His emphasis on Seon was owing to his belief that it was only be becoming “true people” that we could overcome the accumulated ills of the modern age and that it was through Seon meditation that this genuine life could be made possible.

Master Seo-ong located the ills of modern society within the breakdown of human character and discipline brought on by the development of scientific civilization. He explained that the other side of the material convenience and abundance created by the western scientific civilization based on the philosophy of greed and desire is the subjugation and destruction of humanity and nature that this culture also brings forth. The final outcome of this, according to Master Seo-ong, is that humans are reduced eventually to slaves and both the social order and the environment are brought to destruction.

“Buddhism treats humanity as dignified life that transcends time and space. Human existence must search for that supremely vivacious place where we can find our fundamental identity. This is the culmination of the 'true person,' the condition of ilda wonyung, “the perfect interpenetration of one and all,” that combines the unlimited universe into one. It is only in awakening to the fact that humanity and the natural world are not two, that one can save both humanity and the world as well.”

Noting that though all people are “true persons” they must actualize this reality, he published a pamphlet in 1996 titled, “The Door to the True Person Association.” Together with an explanation of what a “true person” was, the end of this pamphlet included a pledge that crystallized Master Seo-ong's spirit.

“Let's put the life of compassion into practice. Let's create a history of the human race living peacefully and equally. Let's establish a world that loves beauty, acting righteously, knowing sincerely and without any attachments how to respect and help one another.”

An Authentic Person of No Status

http://www.koreanbuddhism.net/master/dharma_talk_view.asp?cat_seq=32&content_seq=149&priest_seq=0&page=1

A foolish monk with hairy eyebrows and grey robes,

Walks along the stream leaning on his staff, his steps skillful on their own.

Observing the clouds and mist, he is both sober and intoxicated.

To fool with mysterious changes makes the blunder even worse.

The golden breeze [of autumn] gently turns the leaves their first shade of red,

Now that the autumn moon shines brightly, the waters are even clearer.

Forgetting both ordinary person and sage, he leisurely plays his flute,

Riding Mount Sumeru backwards, he ascends freely of his own accord.

The ‘high-sky’ season has just arrived. The autumn leaves are changing colors and the moon is bright. This truly may be called a wonderful season. If we are to be called true Buddhist disciples, we must try to live our lives as “authentic persons of no status” [translator’s note: Chinese Chan Master Linji’s saying], who are free and autonomous in the eternal present.

Buddhism originally transcended Brahmanism in India and completely solved the problem of human life by illuminating from an ultimate standpoint the original, true form of human beings. Moreover, the practice that possesses from a historical standpoint the most complete realization of the profound source of Buddhism is Seon (禪). Therefore, Seon can be regarded as both the religious life-essence of Buddhism as well as a religion of free and autonomous authentic persons at its essence, which transcends the doctrinal teachings

(Gyo, 敎).

The great significance of Seon is liberation from deluded consciousness and realization of one’s true self on one’s own. What we consider the ‘I’ is not the ‘true I,’ but instead the ‘attachment to I,’ which brings about disturbance and tumult because it involves the suffering and deceptiveness that derive from deluded consciousness. Thus, we must smash the ignorance of this limited ‘I’ and manifest the authentic human form.

Sometimes people who practice chamseon (“investigating Seon”) say that they are not sure if they are practicing Seon correctly, but you must understand that there is nothing clearer than practicing Seon. People talk about “chamseon, chamseon,” so we all consider it to be difficult and an exceptional religious practice, but chamseon just means to live sincerely and compassionately by fundamentally criticizing and liberating our lives, which are immersed in desire and the attachment to self.

If I were to express it simply in psychological terms, we each live our lives in accordance with our own subjective perspective. Typically, our realities are immersed in either our knowledge or our own subjective views, which derive from dualistic activities. These do not adopt an expansive human perspective that sees all phenomena in the universe as a single fundamental living substance, but instead are projections of the extremely narrow and small dualistic subjective views of an individual, which are ascertained according to the needs of each moment. Furthermore, Western philosophy treats worldview or the problem of human existence only from one limited aspect of human life, such as rationality or desire. However, Seon does not look at human beings from a single point of view, but from a holistic perspective—the perspective of a holistic human being who acts rationally and intuitively while transcending rationality and intuition.

Once, someone asked, “Is the state where subjective discriminations are extinguished the ultimate realm of Seon?” It is not. This is because the storehouse consciousness (ālayavijñāna), even though it operates in a mind-state in which the discriminations of consciousness have been extinguished, is nothing but the accumulations of our manifesting consciousness (hyeonhaeng uisik), so it does not have the capacity to recognize truth as it is.

Typically, either scholarship or thought is produced in the manifesting consciousness or the storehouseconsciousness. No matter how the construction of truth is systematized philosophically, when its scope is broadened or deepened, the system falls apart. Thus, new scholarship and philosophical systems keep developing, but they are not the correct paths for contemplating the “original face” (本來面目), which is the fundamental question facing humanity. This is because the original, true form of human beings is the single, universal life substance that transcends both consciousness and unconsciousness. As such, chamseon means to awaken to the ‘authentic person,’ by completely liberating oneself from all discriminative knowledge, thoughts, and even the unconsciousness.

If you critique more fundamentally the binary dichotomies of good and evil, existence and non-existence, rationality and irrationality, material and mentality, and so forth, then at the foundation of all values and speculation lies this absolute dichotomy. This is the limitation of modern men who adopt the standpoint of rationality. However, an authentic person is one who has originally transcended all these dichotomous limitations, and ultimately he is originally an authentic person who does not claim to have newly attained enlightenment. This authentic person is originally unborn and unextinguished, and is not limited by time and space. He is originally pure and unsullied, free and autonomous; and while being devoid of all form, he creates forms in all their variety.

Seon suddenly transforms people who are subject to such dichotomies into authentic persons who are truly themselves, thereby severing in a single cut all ignorance and defilements. Therefore, Seon realizes the history that involves the proactive great capacity and great functioning by guiding even scientific acumen and the life impulse toward an independent position.

While a person like the monk Linji (Kor. Imje; Jpn. Rinzai) was studying scriptures, he realized that words and language are only medical prescriptions, so he decided instead to do Chan meditation. This example in turn asks us what actually solves the questions of human life objectively and with universal validity. Because chamseon is not dogmatism, which would demand that one follow its dictates blindly, one must oneself practice it and attain awakening.

In order to practice chamseon correctly, one must earnestly investigate the hwadu (“keyword”). To investigate the hwadu means that one’s whole life substance must transcend intellectual consciousness. In the “ball of doubt” (uidan) generated by investigating the hwadu, one’s whole existence must be unified and tense. One’s body and mind have to become a single life substance, just like the moment when you start to run at the sound of the gun go off at the beginning of a hundred-meter race. If one investigates the hwadu in this manner and moreover practices genuinely, then one attains the state of the ‘silver mountain and iron wall,’ where the discriminations of consciousness are eradicated. Also, when the hwadu appears clearly while becoming more transparent, then the production and extinction of consciousness will disappear. If one practices Seon deeply, one actually can reach such a state. Although this may be a state where the production and extinction of consciousness have disappeared, one does not fall into sloth and torpor. Instead, the hwadu and the ball of doubt (uidan) become ever more clear and numinous, so that one progresses to penetrate even the level of the unconscious. When one penetrates to this ultimate state, the absolute dichotomy disappears. Pure and clear, there is not even a single thing: this is the state of ‘mountains are mountains, rivers are rivers.’ However, if one sits abiding in this state, then one has not yet passed through the gate of patriarchs. By suddenly passing through this realm, one ‘sees the nature’ and awakens to the storehouse of the right-dharma eye (Jeongbeopanjang) of clear-eyed enlightened masters of our school.

To give you a little more detail, we cannot even call this ‘seeing the nature’ or ‘awakening to the self.’ The original face is itself real and originally exists as it is. It is only because one does not have a fervent and sincere aspiration for enlightenment, and has not truly tried to practice chamseon, that one says the practice of Seon is difficult. Actually, the original face is the fundamental essence of human existence and one’s true form. What is more, some say that though the buddha-nature is inherent in people’s minds, because it is different from reality, they refer to it as internal transcendence and advocate that it is mysterious. However, an authentic person does not abide either internally or externally in our ordinary reality. The authentic person is the ‘absolute present” by being the nucleus of the present moment. This is what we call the ‘eternal now’ or the ‘absolute now.’ The authentic person becomes the fundamental nucleus that transcends time and space, and is the original, true form of human beings, which overcomes all fragmenting self-destructiveness and is thus free and autonomous.

The wooden ox walks in fire

from The Dharma Assembly of the Great Seon Masters (October, 2002)

http://www.koreanbuddhism.net/master/dharma_talk_view.asp?cat_seq=32&content_seq=154&priest_seq=0&page=1

We live in a world of dualistic consciousness. The realm created by consciousness is characterized by our perceived division of things into subjects and objects. Both consciousness and Store-house Consciousness (or unconsciousness) pertain to the level of subjectivity. They are ruled by the principle of arising and passing away. Our minds are imbalanced and impure, and we cannot escape from the round of birth and death.

In order to overcome all duality, we have to break through consciousness and Store-house Consciousness, where there is no distinction between good and evil, birth and death, subject and object, time and space. This state of mind is ultimately free and without obstruction. One can reach it neither through the mere intellect nor through the immobilization of mind. The surest and most direct way to this kind of experience is through the mass of doubt produced by the active kong-an (Ch., kung-an/Jn., koan) practice handed down in the Patriarchal seon tradition.

It is estimated that there are in all some 1700 types of kong-an within the seon tradition. Actually there are countless varieties, because the innumerable problems of human beings are all vivid motifs for kong-an. If any single selected kong-an is resolved, all of them will burst open simultaneously. I shall now introduce you to the way in which one may understand the practice of kong-an.

First of all, the practitioner should have great tenacity in pursuing the fundamental questions of human birth and death. A monk asked Chao-Chou:

"What is the motif of Bodhidharma's coming from the West?"

Chao-Chou replied:

"The arborvitae tree is in the garden!"

This is a question about Patriarchal seon. That is to say, the monk asks Chao-Chou about the purpose of Bodhidharma's mission, the first patriarch of seon, coming from India to China. The seon practitioner must earnestly ask himself why Chao-Chou said "The arborvitae tree is in the garden!". He should make his whole body and mind into one great inquiry. The first step is that he has to be absorbed into the kong-an without any distinction between subject and object. He has to become one with the kong-an, free from all discursive thoughts. If he continually maintains the great inquiry, the kong-an keeps going under its own momentum. This is the second step. Persevering zealously in his practice of kong-an, all thoughts are completely extinguished. Mind at this stage is motionless like stone or iron, but the practitioner is increasingly alert and attentive with his kong-an. If he pushes himself further, he breaks through Store-house Consciousness by the force of his kong-an. His whole mind, conscious and unconscious, is broken through, and simultaneously, the mind manifests, free and without obstacles. Here, there is no distinction between good and evil, birth and death, subject and object, time and space. At this stage, the mind is ultimately liberated. If he breaks through to a further level, there is unity between the break-through and the manifestation of all things. Taken still further, he is free and dynamic because of the limitless liberation of break-though with boundless manifestation of all things. At last, he accomplishes the great life-time work!

None of these stages are separate from each other, for they are all interrelated. But this stupid old man will not allow even this.

"Why don't I allow it? - Answer my question immediately!" "Why? Because I shall deliver my Dharma talk without allowing myself to adhere to even this ultimate stage of realization!"

[Case]

When Linchi was about to pass away, he admonished San-sheng, "After I pass on, don't destroy my secret code of insight into upright dharma (Zhengfayanzang)." San-sheng said, "How would I dare destroy the teacher's secret code of insight into upright dharma?" Linchi said, "If someone suddenly questioned you about it, how would you reply?" At once, San-sheng started shouting. Linchi said, "Who would have thought that my secret code of insight into upright dharma would perish with this blind ass?"

[The Great Patriarch Seo-Ong's Added Saying]

"After I pass on, don't destroy my secret code of insight into upright dharma." Linchi said. "If someone suddenly questioned you about it, how would you reply?" San-sheng said, "How would I dare destroy the teacher's secret code of insight into upright dharma?"

- These refer to the state of all-pervading break-though and the simultaneous manifestation of all things.

Linchi said, "If someone suddenly questions you about it, how will you reply?" and San-sheng immediately started shouting.

- These refer to the state that is free without obstacles due to the unity between all-pervading break-though and the manifestation of all things.

Linchi said, "Who would have thought that my secret code of insight into upright dharma would perish with this blind ass?"

- This shows the state that is ultimately free and dynamic due to the endlessly liberating break-though and the boundless manifestation of mind.

[Verses by Tiantongjue]

The robe of faith is imparted at midnight to Hui-neng,

Stirring up the seven hundred monks at Huang-mei.

The eye of truth of the branch of Linchi;

The blind ass, destroying it, gets the hatred of others.

From mind to mind they seal each other;

From patriarch to patriarch they pass on the lamp,

Leveling oceans and mountains, A fowl turns into a roc.

name and word alone are hard to compare.

In sum, the method is knowing how to fly freely.

[The Great Patriarch Seo-Ong's Commentary on the Verses]

"The robe of faith is imparted at midnight to Hui-neng" refers to the manifestation of all things.

"Stirring up the seven hundred monks at Huang-mei" refers to penetration of all things. "The eye of truth of the branch of Linchi" shows the manifestation of all things.

"The blind ass, destroying it, gets the hatred of others" indicates the state that is ultimately free due to the endless break-though into all things as well as the boundless manifestation of all things. "From mind to mind they seal each other;From patriarch to patriarch they pass on the lamp" refers to the manifestation of all things. "Leveling oceans and mountains" refers to the break-though of all things.

"A fowl turns into a roc" shows the state that is ultimately free due to the unity between the penetration of all things and manifestation of all things. "Name and word alone are hard to compare. In sum, the method is knowing how to fly freely" refers to the state that is ultimately free and dynamic due to the endlessly liberating break-though and the boundless manifestation of all things.

Thus far, I have illustrated the meaning of the practice of kong-an for the sake of beginners. Practitioners, however, should experience this state of complete break-through through their zealous practice of kong-an. This is an active expression of dharma.

[The Great Patriarch Seo-Ong's Added Saying]

Revolving in day and night, restless in eternity,

The bright moon illuminates reed flowers,

Reflecting their identical appearances.

A young accipiter capable of

Flying far away through the sky

Pierces the air with the flap of its wings,

Free from longing for home.

[Auto-commentary on the Added Sayings]

These added sayings depict the state of the all-pervading break-through and the simultaneous manifestation of all things;the state that is free without obstacles due to the unity between all-pervading break-through and the manifestation of all things;the state that is ultimately free and dynamic due to the endlessly liberating break-though and the boundless manifestation of all things.

Speak immediately!!!

"The wooden ox walks in fire"

"A-ak!" (an abrupt roaring).

Chan Buddhism and the Philosophies of Laozi (老子) and Zhuangzi (莊子)

http://www.koreanbuddhism.net/master/dharma_talk_view.asp?cat_seq=32&content_seq=476&priest_seq=0&page=1

Among all Chinese philosophies and religions. the thoughts of Laozi and Zhuangzi are perhaps the most profound. It is often said that the Chinese have a tendency to put much weight on reality and are pragmatic by nature. Therefore, the systems of thought developed in China are usually addressed towards practical matters that can be directly applied in everyday life. While ethical and political ideologies abound in Chinese history, rarely can we find metaphysical views on life or thoughts inclined towards a craving for mystical truth.

Contrary to this dominant Chinese tradition are Laozi and Zhuangzi, figures who deal with the most profound problems of life, transcending the common-sense values and thoughts of average Chinese people. Living in times of unprecedented turmoil in China, the Age of the Warring States, Laozi and Zhuangzi witnessed constant war, where schemes and machinations were the norm. The lens of history shows that many instances of unprecedented philosophical and religious development appeared precisely within those countries suffering from chaos and hardships, as a result of efforts taken to overcome such adversity. Laozi and Zhuangzi are perfect examples of this.

When Buddhism was first introduced to China, local scholars tried to interpret Buddhism by borrowing concepts from pre-existing philosophies, mainly those of Laozi and Zhuangzi. For instance, in the Daodejing written by Laozi, there is a statement, "All the things of the world originate from being (有), and being (有) comes from nothingness (無)." The universe has a form and it is thought of as ‘being’ (有), and the origin of the universe without form is considered ‘nothingness’ (無). Accordingly, the concept of voidness1) in Mahayana Buddhism was translated and understood in terms of nothingness as used in the terminology of Laozi.

When Buddhist sutras were translated into Chinese for the first time, the word Nirvana was translated as 'non-doing', meaning 'doing nothing,’ or ‘doing without deliberate manipulation.' Bodhi was translated as 'Tao,' and Tathata (the truth as it is) as 'Originally Nothing.' Buddhism was thus regarded on its deepest levels through the template of Laozi and Zhuangzi. Of course, it would have been difficult for the pragmatic Chinese to accommodate the esoteric thought of Buddhism without borrowing from the conceptual framework of Laozi and Zhuangzi. However, the true meaning of Buddhist thought was somewhat distorted though this process, as it was not simply words, but an entire philosophy that was needing to be translated.

Furthermore, whereas Indians often employed meditation to transcend the suffering of the mundane world, leading to the development of a theoretical, epistemological logic, the Chinese, more active and realistic, preferred intuition to logic. Therefore, rather than the logical meditation into profound Buddhism as seen in India, Chinese Buddhism adopted a practical religious approach in pursuit of the dharma, that is, to experience the ultimate stage of Buddhism and cultivate the mind with intuition. This was the beginning of the Chan Tradition in China, and the subsequent Seon/Zen/Thien traditions in Korea, Japan, and Vietnam, respectively.

Some Buddhist sects consider the intuitive stages of Zhuangzi, such as 'Sitting in Oblivion(坐忘),' 'Seeing the stage of transcending the limitations of reality (朝徹),' and 'Seeing independence (見獨)' to be consistent with Chan, but I would like to quote a critical retort (pingchang 評唱) in case 80 of <The Blue Cliff Record>, a book that reveals the innermost depth of the truth of Linji tradition, to argue that this is not, in fact, the case.

According to the contents of the pingchang, Chan meditation initially consists of our conscious mind (心識). When we proceed deeper into our being, we arrive at the margins of ‘no mind’ (無心 ), the absolute stage undiscerned from the universe or Nature. Chan does not stop here though. With more exertion and devotion, we earn the Panna Wisdom of Buddha that pervades the Store-house consciousness, and then transcends even Buddha, to be limitlessly free and dynamic. This ultimate stage of Chan is called 'Tao, the mind of everyday life,' which is to eat food when hungry, drink tea when thirsty, and to be absolutely free and dynamic, restricted by nothing.

Then what of the stage told by Zhuangzi? In the book titled after his own name, there is a story about 'Sitting in Oblivion' in the Chapter “The Great and Venerable Teacher.”

Yanhui, a pupil of Confucius, said "I have made some gain." Confucius asked, "What do you mean?" Yanhui replied, "I forgot virtue and justice." Confucius commented, "Good, but not enough." After some time, he said to Confucius again, "I made further gain." "What is it?" "I forgot civility and music." "Good, but still not enough." Several days later, he said to Confucius once more, "I have made an even greater gain." Confucius asked, "What is it?" Yanhui replied, "I reached 'Sitting in Oblivion.'" Amazed Confucius asked, "What is 'Sitting in Oblivion'?" Yanhui answered, "It is forgetting hands, feet and body, forgetting the action of ears and eyes, leaving the distinction of form to discard wisdom and becoming one with Tao. This is 'Sitting in Oblivion.'" Confucius praised, "When someone becomes one with Tao, there is no good nor evil. After undergoing transformation into becoming one with Tao, there is no attachment. Wise indeed. Now it is I who should be your follower instead."

The 'Sitting in Oblivion' of Zhuangzi is no more than the severing of consciousness, resting in the margins of no mind (無心 ) where all discriminations vanish, whereas Chan breaks through conscious mind (有心 ), transcends 無心 (no mind), and rises above even Buddhahood to be unlimitedly free and dynamic. To reach Panna Wisdom, one must go beyond even the margins of no mind (無心), to the stage of the eighth sense.

I will give one more example about Zhuangzi, again from “The Great and Venerable Teacher”:

For three days, rising above the world, remaining beyond, I dwell in this stage. After the seventh day, I am beyond all things, and after the ninth day, I am beyond life. Already beyond life, I can see the stage that transcends the limitations of reality, and then I see independence. Then there is no past and present, and then after this stage, I enter the realm without life nor death.

Zhuangzi mentions being outside of all things, outside of life, and then seeing through the stage that transcends the realistic limitations of human beings. In conclusion, he speaks of transcending the limitations of consciousness.

Although people are prone to confuse Zhuangzi's thoughts with Chan, the two lie in totally different spheres. Zhuangzi remains at the boundary of the eighth sense, the margins of unconsciousness, the margins of the great Nature where there is no deliberate human manipulation. Chan transcends this stage of Zhuangzi to reach Panna Wisdom, and transcending even Panna Wisdom, it arrives at the great freedom.

Of course, this analysis is but a brief summary of the very complex differences between Zhuangzi and Chan. All of you must practice more earnestly to see the reality for yourselves.

--------------

1) Voidness: Sunyata in Sanskrit. In the Indian Madhyamaka philosophy, it refers to the ultimate nature of phenomena. It is often used to describe either non-existence or the absence of all mental and physical sensation experienced at some stages of meditation.

The etymology of gongan

http://www.koreanbuddhism.net/master/dharma_talk_view.asp?cat_seq=32&content_seq=477&priest_seq=0&page=1

The word 'Seon' comes from the Chinese word ‘Chan’, a transliteration of the Sanskrit word 'Dhyâna'. Loosely translated, it means “meditative absorption.” Another definition would be “silently thinking.” ‘Jwa-seon’ (sitting-seon) thus means “meditating silently while seated.”

The sixth patriarch, Huineng, defined 'sitting' as externally being in the world of good and evil and yet having no thought arising in the heart, and ‘Seon’ as internally seeing the self and not straying away from it. The formal practice Seon entails one sitting upright in a room with a calm atmosphere and some burning incense, breathing deeply and steadily while thinking about something. But what is it you should think about?

Think about life.

'What is life?' 'What should I do in my life?' 'Where have I come from and where am I ultimately heading?' 'What does it mean to live and to die?' 'What is the relationship between the universe and my life?' 'What is the right way to live?' 'What is life’s true meaning?'

Life is invaluable. There is nothing that can compensate for it. As such, we must take the most upright course through this precious life. Living with a false vision of reality, one cannot see one’s own true self, one’s own true existence and this life is simply wasted away. It becomes a “false life.”

You must steel within yourself an ardent determination, thinking, “Life is full of defilements. Where have these defilements come from? I must liberate myself from them and realize my pure original countenance, the true image of my original self.” There is only one path to such a true awakening and you must search deeply into this only path, meditating in silence about the defilements of life, their causes, their cessation, and the means to bring it about.

In the times of Sakyamuni , there was once a disciple with such a bad memory that he could not even remember his own name and had to carry a name tag around his neck. To teach this disciple the way of the upright dharma, Sakyamuni asked him to memorize only a singe sentence, "Brush the dust away and wash the dirt off." For three years, when he was sitting, standing, sleeping and awake, the disciple thought earnestly about only this one short sentence. As he continued to meditate on this one single hwadu, the dust in his mind was brushed away and the dirt all washed off, such that suddenly he discovered the stage of true self that is without dust, dirt, or defilements, beyond even any truth itself.

The tradition known as “Patriarchal Seon,” developed by successive patriarchs of old, is the teaching that every person, regardless of their powers of intellect or memory, can penetrate into the realm of Buddha in one sweeping stride, awakening to the pure original face, through questioning with absolute diligence one single problem, one hwadu, like the disciple spoken of above. Is this not a rather mysterious and wonderful thing?

This simple problem is equivalent to a passport that allows us through the gateway to enlightenment, and is referred to as a gongan (Ch. kungan, Jp. koan), a metaphorical borrowing from the words gongbu eui andok (公府之案牘 ), which literally means “a case record of the public court,” and in its usage in Chan/Seon/Zen, indicates a singular example case through which a more universal truth can be known.