ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

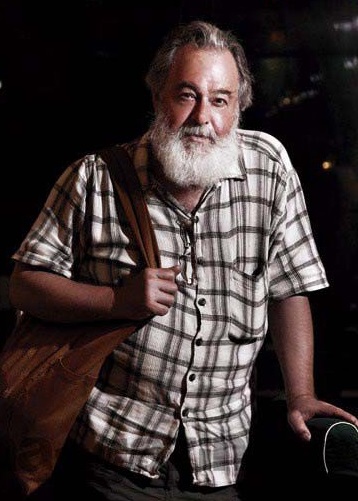

Red Pine (Bill Porter, 1943-)

比尔 波特 Bǐěr Bōtè

He adopted “Red Pine” (赤松

Chì Sōng) as his Chinese name, only to discover later that it was also the name of the Yellow Emperor's Rain Master, a famous Taoist.

Early life

In an interview with Andy Ferguson for Tricycle Magazine in 2000, Red Pine revealed some of the details of his early life. His father, Arnold Porter, grew up on a cotton farm in Arkansas. At an early age, Arnold became part of a notorious bank robbing gang that robbed banks from the south northwards to Michigan. In a shoot out with the police, all the gang members were killed except Porter who was wounded and subsequently sent to prison. Nevertheless, after six years he was pardoned by the governor of Michigan and released; an inheritance from the sale of the family farm allowed him to enter the hotel business and to become a multimillionaire. Arnold moved to Los Angeles, where Bill was born in 1943. Later the family moved to a mountainous area near Coeur D'Alene Idaho. Arnold Porter became involved in Democratic Party politics and head of the Democratic Party in California, developing close associations with the Kennedy family.

Red Pine's early life was one of wealth and privilege. He and his siblings were sent to elite private schools, but he considered the schools to be phony and too wrapped in wealth, ego, and power. Eventually his father divorced his mother and subsequently they lost everything. While his brother and sister found it difficult to live with less money, Pine was relieved when this happened.

After receiving a draft notice in 1964, he voluntarily enlisted and served a three-year Army tour in Germany. Pine served in Germany for three years as a medical clerk, which paid for his college education at UC Santa Barbara where he obtained a degree in anthropology. When he encountered Buddhism, the tenets were quite clear to him and he understood exactly what it was about. Following graduation, he went on to graduate studies in language (Chinese) and anthropology at Columbia University, but dropped out in 1972 to go to the Fo Guang Shan in Taiwan, a Buddhist monastery. He studied for a year at Fo Kwang Shan with master Hsing Yun.

After a year he left and spent the next two and half years at the College of Chinese Culture, a smaller, less crowded monastery outside of Taipei in the mountains, where he became a graduate student in philosophy. He took classes in Taoism, Chinese art and philosophy; his future wife, Ku, was a classmate. Unhappy with academic life, he left to go to Hai Ming Temple, a monastery 20 km south of Taipei where he stayed for 2 1/2 years. Wu Ming was the head Rinzai monk, Chiang Kai-Shek's personal master. Here he simply studied and meditated: "I had got hold of all these classic texts with both Chinese and English characters and I went through most of the sutras."

https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Red_Pine_(author)

Works

P'u Ming's Oxherding Pictures and Verses. Empty Bowl Press, Port Townsend, WA, 1983; 1987; 2011. (translator)

Cold Mountain Poems. Copper Canyon Press, 1983. (translator)

The Poems of Big Stick and Pickup: From Temple Walls, Empty Bowl, Port Townsend, 1984. (translator)

Mountain Poems of Stonehouse. Empty Bowl, 1985. (translator)

The Zen Teaching of Bodhidharma. Empty Bowl, 1987; North Point Press, 1989. (translator)

Road to Heaven: Encounters with Chinese Hermits. Mercury House, 1993. (author)

Guide to Capturing a Plum Blossom by Sung Po-jen. Mercury House, 1995. (translator)

Lao-tzu's Taoteching: with Selected Commentaries of the Past 2000 Years. Mercury House, 1996. (translator and editor)

The Zen Works of Stonehouse: Poems and Talks of a Fourteenth-Century Chinese Hermit. Mercury House, 1997. (translator)

The Clouds Should Know Me by Now: Buddhist Poet Monks of China. Wisdom Publications, 1998. (editor, with Mike O'Connor; and contributing translator)

The Collected Songs of Cold Mountain. Introduction by John Blofeld. Revised and expanded edition, Copper Canyon Press, 2000. (translator and editor)

The Diamond Sutra. Counterpoint, 2001. (translator and extensive commentary)

Poems of the Masters: China's Classic Anthology of T'ang and Sung Dynasty Verse. Copper Canyon Press, 2003. (translator)

The Heart Sutra: the Womb of Buddhas. Washington: Shoemaker & Hoard, 2004. (translator w. extensive commentary)

The Platform sutra: the Zen teaching of Hui-neng / translated by Red Pine [Bill Porter], Shoemaker & Hoard, 2006. 346 pages

http://buddhaspace.blogspot.hu/2012/06/review-platform-sutra-by-hui-neng-red.htmlZen Baggage: A Pilgrimage to China. Counterpoint, 2008. (author)

In Such Hard Times: The Poetry of Wei Ying-wu. Copper Canyon Press, July 1, 2009. (translator). Awarded a 2007 PEN Translation Fund Grant from PEN American Center. Winner of the American Literary Translators Association (ALTA)'s inaugural Lucien Stryk Asian Translation Prize in 2010.

Lao-tzu's Taoteching: Translated by Red Pine with selected commentaries from the past 2000 years. revised edition, Copper Canyon Press, 2009.

Guide to Capturing a Plum Blossom by Sung Po-jen. Copper Canyon Press, 2011, (translator)

The Lankavatara Sutra: Translation and Commentary. Counterpoint, 2012, (translator)

Mountain Songs

https://web.archive.org/web/20230306150036/http://www.mountainsongs.net/translator_.php?id=14

Dancing With Words:

Red Pine’s Path Into The Heart of Buddhism

The updated version of an article that originally appeared in The Kyoto Journal

by Roy Hamric

http://www.firstzen.org/ZenNotes/2009/2009-04_Vol_56_No_04_Fall_2009.pdf

“All great texts contain their potential translation between

the lines; this is true to the highest degree of sacred

writings.”--Walter Benjamin, "The Task of the Translator".

When I first saw Red Pine’s translation of The Poems of Cold Mountain, I remember thinking, “This is something important –– who’s this Red Pine?”

That was 1983. Two years later came the book that really shook up the Buddhist literary community, Red Pine’s stunning, self-published translation of The Mountain Poems of Stonehouse, a tough spirited book of enlightened free verse––300 poems chronicling the pains and pleasures of Zen hermit life. The Stonehouse (Shih-wu) and Cold Mountain (Han-shan) translations put a spot light on Zen autobiographical poetry unlike any books before.

Red Pine’s elegant hand-sewn, self-published translation of The Zen Teachings of Bodhidharma, in a Chinese-red cover, followed in 1987. Over the years, I avidly bought each new Red Pine translation: Guide to Capturing a Plum Blossom (Sung Po-jen), which won a PEN/West translation prize; Lao-tzu’s Tao Te Ching; and his own Road to Heaven: Encounters with Chinese Hermits, which put contemporary flesh on Taoist/Zen hermit life. * (cf. end)

My curiosity about the man who called himself Red Pine grew with each new book. But facts about his life were clouded in dust jacket blurbs: he lived in the mountains overlooking Taipei in a small farm community called Bamboo Lake; he was connected somehow with Empty Bowl press in Port Townsend, Washington. Eventually his American name, Bill Porter, appeared on one of his books. Red Pine: Bill Porter. But, no more information--none of the American Buddhist magazines, which proliferated during the ‘80s and ‘90s, were of any help.

From the first, his translations seemed inspired. I read his books differently. There was a feeling of verisimilitude, rare in translation. His choices and love for the writers he translated filled a gap in my view of Chinese Zen writers. I felt connected to his poets as real people.

My admiration also grew for the role of the translator who on obscure, subtle Zen texts and poetry. The translator is the shadow presence in the equation between writer and foreign reader. In translating (trans-relating) a text from one language to another, they serve as a supreme amanuensis who bridges language and brings writers and foreign readers together. Red Pine’s out-of the-main-stream work is canny and clearheaded, and it has immeasurably enhanced Zen/Taoist literature and practice.

Then came his stunning translation of The Diamond Sutra, with commentaries by himself and other Buddhist writers from over the centuries. The fruits of Red Pine’s years in Taiwan, in Hong Kong, his travels in China, and his quiet devotion to Buddhist study and practice shine through the work. The translation occupies a unique place in Buddhist literature––serious, scholarly, but with the smell of experience. Work you can trust.

After living 22 years in Asia, Red Pine returned to live in America in 1993, settling in Port Townsend. A coastal town of about 8,000 people on the northeast corner of the Olympic Peninsula, it’s a laid-back mix of Victorian houses, fishing boats, artists and writers, and a cottage industry of tourists. His tie to the town was forged through a band of artists, poets, tree-planters and Asian connoisseurs who earlier had started Empty Bowl press, the imprint he used for three of his self-published books. The books are now collector items. With first printings of around 1,000 copies, he sent the books from Taiwan to friends in America. “They would sell them in about a half dozen book stores and send me some money,” he says.

The audience for his translations is small, but dedicated. "Typically, the first year a book will sell two to three thousand copies then start averaging 500 to 1,000 copies a year," he says. With royalties as almost his only source of income, Red Pine lives frugally. He’s trimmed the fat from his life, in order to be able to translate and publish his books. In the acknowledgments to his early books, he thanked the U.S. Department of Agriculture Food Stamp Program."It was not tongue in cheek," he says."I couldn’t get by without it. I have a good life, but it takes commitment. I just don’t do anything. I’m perfectly content to do my work everyday."

Red Pine was born in Los Angeles on Oct. 3, 1943. He was sent to boarding schools in Los Angeles and San Francisco. “I had good schooling, but emotionally I wasn’t ready to go to college,” he says. “I entered the University of Santa Barbara in 1961, but I flunked out because I didn’t have a clue. Often on Friday nights, I’d take what’s called a ‘piggy back’ freight train to San Francisco for the weekend. I spent all my time mooning over this woman and flunked out of school. I did the same thing at two junior colleges.”

After receiving a draft notice in 1964, he voluntarily enlisted and served a three-year Army tour in Germany. He returned to Santa Barbara to major in anthropology and was soon reading The Way of Zen by Alan Watts, and Introduction to Buddhism by Edward Conze. "It was then that I finally felt I’d found something that made sense to me about what was going on in this life. But, I was really still looking on these books as something I was doing on my own, on the side."

"I graduated in ‘70, and applied to grad schools. The only one that gave me any money was Columbia University. I had checked the box on an application for a language fellowship, and I penciled in “Chinese”--and I got it."

At Columbia, Red Pine studied language and anthropology, approaching it from the point of view of what it could teach about the truth of life. He spent his junior year at the University of Goettingen in Germany. “Everything I was studying then started to dovetail with Buddhism,” he says. “They all were saying the same thing to me in terms of how to discover what’s real. I was ready for Buddhism when it came along. But the thing about Buddhism was that it was so much broader in scope, far more poetic as well--a way of life as well as a way of thinking.

"When I went back to Columbia, I found I couldn’t write papers. My anthropological underpinnings had been wiped away. Suddenly, I was thinking everything was an illusion, or all categories are fictions. I was meditating on weekends with a Buddhist Hua-Yen monk, Shou-yeh, who had a temple north of New York City. Finally, I threw in the towel and decided to go to a Buddhist monastery."

"I knew another student who had been to a monastery in Taiwan, and he knew of a monastery that was just starting. I wrote them a letter and they said, ‘Come on over.’" His father gave him a one-way ticket and $200, and he arrived in Taiwan in 1972. He stayed for a year at the Fo Kwang Shan monastery with master Hsing Yun."They had classes," he says. "It was sort of a Buddhist training monastery with Sanskrit classes and the study of different sutras, all in Chinese. I had been studying Chinese intensely for two years, but they sort of let me slide through. I had a nice room just off the Buddha Hall.

"All the people there thought it was the strangest thing to have a foreigner studying Buddhism. It was like being on a foreign planet. When the public came through the monastery it was sort of touristy and I got tired of being gawked at so I decided to go to a monastery in Taipei." He eventually landed at the College of Chinese Culture where he became a graduated student in philosophy. He lived in the dorm with Chinese students and took classes in Taoism, Chinese art and philosophy.

"A professor offered a course on the philosophy of Alfred North Whitehead," he says. "The Chinese woman who later became my wife sat behind me in that class." While at the college, Red Pine studied the Tao Te Ching with Prof. John C. H. Wu, who in 1961 had published a valuable English translation of the work.

After one year, he was unhappy with academic life, and a friend suggested he go to Hai Ming Temple, a monastery 20 km south of Taipei. "Wu Ming was the head Rinzai monk. I stayed there 2-1/2 years. Wu Ming was Chiang Kai-shek’s personal master. That place had an artistic sense. He asked if I had any questions, but I’m the kind of person who’s not very curious. So I just studied and meditated. I had got hold of all these classic texts with both Chinese and English characters and I went through most of the sutras." Red Pine was still courting his future wife, Ku, and on Saturdays he often took the train to Taipei to see her. She introduced him to a coterie of intellectuals who met at the Astoria Bakery/Coffee shop.

"When it came time to decide if I wanted to be a monk, I decided to move out of the temple," he says. "But before I left, I took the lay precepts. Then I found this place on the top of Yang Ming Mountain near where all the rich people lived overlooking Taipei. I rented a converted stone farm shed in Chu Tzu Hu, or Bamboo Lake.”

About this time, he adopted “Red Pine” as his Chinese name, only to discover later that it was also the name of the Yellow Emperor’s Rain Master, a famous Taoist. After seven years, he and Ku married. A son, Red Cloud, was born in 1982, and a daughter, Iris, in 1987. For about six years he worked at International Community Radio in Taipei as a national news editor. “That’s the only full-time job I’ve ever had,” he says. Married 29 years, Red Pine and Ku only recently have been able to live together full time. Ku’s parents placed a condition on their marriage that she continue to take care of her parents, and she did that.

At Bamboo Lake, Red Pine began translating Cold Mountain poems. He sent about 100 poems to Shambala, Weatherhill and Tuttle publishers. They all turned him down. Frustrated, he sent some of the translations to John Blofeld, a renowned writer-translator, and asked him if he’d look at them. Blofeld replied he’d like to see more and a friendship formed. He became Red Pine’s mentor.

"He asked me to start sending him the poems," he says, "and he went over them with me and encouraged me to translate all 350 poems. That was my trial by fire. I never intended to be a translator––it just sort of happened."

"I have a couple of hundred letters," Red Pine says. "I’d send the poems each week and he returned them with comments and asides." They corresponded regularly for two years.

When Copper Canyon press accepted the book, Red Pine asked if Blofeld would write the introduction, and Blofeld invited him to visit him at his home in Bangkok, where he spent a week. Later, Blofeld visited Red Pine several times at Bamboo Lake, the last time in 1987 as Blofeld was confronting cancer.

"He was a very sincere Buddhist who practiced every night for several hours and loved what he did," Red Pine says. "I don’t think he ever stopped learning." His Cold Mountain translations garnered attention, but The Mountain Poems of Stonehouse was the real revelation for most readers. A poet few people had ever heard of, Stonehouse’s singular poem-journal outlined Zen hermit life in chilling and thrilling clarity.

"Rare is the Chinese who knows Stonehouse," Red Pine says. "He’s a much better poet than Cold Mountain, but he didn’t have the fame Cold Mountain had. Within 100 years, Cold Mountain had a real reputation."

"As soon as Cold Mountain was published, I was dissatisfied with what I’d done. Stonehouse gave me a chance to re-confront the art of translation. It was so much more poetry." Red Pine says he’s still learning the art of translation with each new work.

"When I was translating Cold Mountain, I definitely didn’t have my own voice," he says. "With Stonehouse it was somewhere in between. I think I didn’t really discover my translation voice until I did Bodhidharma, which gave me a chance to find the rhythms of my language."

"Every project I’ve engaged in taught me an entirely different way of translation," he says. "I don’t view Chinese poetry today the way I did then. I use to count the words in my English lines and try to do my best to do the same thing they did in Chinese. I was also intrigued about things you can do in English that reflect the Chinese, not to make the English sound Chinese but to do things with it that to me at least seemed unique."

"I tried to do things that I saw happening in Chinese––the Chinese language is a very telegraphic, terse language––time is almost irrelevant, their subject is also dispensed with. A line can be very ambiguous. So I started to play with that in English and still make sense. "

"Words carry a lot on their surface, but a lot is under the surface that we don’t see when we see the word––a lot comes from contextual familiarity. People identify words with context. I was intrigued by the nature of Chinese poetry and its brevity––here were these flashes of meaning."

______________

http://www.firstzen.org/ZenNotes/2010/2010-01_Vol_57_No_01_Winter_2010.pdf

Ultimately, a good translator must go beyond the words on the page. Someone once said that translation is the undressing of a poem in one language to dress it in another. Red Pine recalls one day when he was browsing through the pirated editions at Caves Bookstore in Taipei, and he picked up a copy of Alan Ginsberg’s Howl.

“It was like trying to make sense of hieroglyphics,” he said. “I put it back down and looked for something else. Then a friend loaned me a video of Ginsberg reading Howl. What a difference. In Ginsberg’s voice, I heard the energy and rhythm, the sound and the silence, the vision, the poetry. The same thing happened when I read some of Gary Snyder’s poems then heard him read. The words on a page, I concluded, are not the poem. They are the recipe, not the meal, steps drawn on a dance floor, not the dance.”

“What I do now is more of a performance,” he says. “Before, I was usually sort of reading the lines like an actor, but now I perform the book--what I do now is closer to dance. The words have to follow along my physical feel for the rhythm, the feeling of what’s happening in the Chinese poem. I don’t see the Chinese as the origin anymore. The Chinese was what the authors used to write down what they were feeling.

“I’ve gotten so used to the words I don’t have to think about them anymore. I’m more concerned with the spirit. I don’t think I have a philosophy of translation, but you have to be very open.”

In The Great Preface to the Book of Odes, the Chinese character for poetry is “words from the heart,” says Red Pine. “This would seem to be a characteristic of poetry in other cultures as well—that it comes from the heart, unlike prose, which comes from the head.

You’re trying to get into the heart of another person. I’m fortunate I’ve found materials that present deep hearts. That’s the way I’ve responded with the passion I have. I’m fortunate to have run into the Buddha, Bodidharma, Cold Mountain, Stonehouse and the other Buddhist poets.”

______________

In Port Townsend, Red Pine lives in a two-story Victorian house which sits on a high hill overlooking town. To the south is the Olympic Mountain range. Through the largest window in his workroom he can see the sea. Through another window he can see the branches of a plum tree. From another window, he can see pine trees and bamboo. On the walls are bamboo paintings, a Tibetan tanka, and a painting with calligraphy of a Wang Wei poem. The room is lined with books. He works almost every day with few breaks.

“I have an extensive library for me, but probably no bigger than what a college professor has in their office,” he says. “I’ve never been interested in knowing everything about everything. I only translate what I want to learn about. For the Tao Te Ching, I had about 40 commentaries.

“I only buy books that relate to the projects I’m working on and a couple of those books will usually be on the time period it’s written in. I hardly have any books at all in English.

“I’m not interested in what a Westerner has to say about these things, because that’s a secondary source. My library is in primary source material—a bunch of sutras, poems, commentaries.”

Red Pine’s interest in primary sources took a physical turn in 1989, when he began thinking about the Buddhist hermit tradition and wondering if any hermits were still practicing in China. Many of his Taiwan friends doubted real Buddhism even existed in China. By chance, he had a conversation with Winston Wang, the son of one of the richest men in Taiwan. Wang was fascinated by the idea of searching for Chinese hermits, and he gave Red Pine $3,500 to finance an exploratory trip. His first trip was for one month, and he went back two more times.

“Most people who translate don’t have a clue to where things happen,” Red Pine says. “They really don’t have an awareness of the landscape. I visited the grave of every significant poet, and I’ve been to every significant Zen temple, but before that I’d never paid attention to it. I discovered the place, and that was exciting to me and since then I make sure I know where the work was done.

“I’d never been to China before,” he says. “We got there at the beginning of the Democracy Movement. We were caught in huge demonstrations. There were a lot of spies, informants, and we could tell something was about to happen. It was one month before Tiennanmen Square. The search for hermits centered around the Chung Nan Mountains in southern Yunnan. The trip brought home the true meaning of hermit life,” Red Pine says.

“I’ve never heard of any great master who has not spent some time as a hermit. The hermit tradition separates the men from the boys. If you’ve never spent time in solitude, you’ve really never mastered your practice.

“If you’ve never been alone with you practice, you’ve never swallowed it and made it yours. Now I can see the part it’s played in the history of China. If you don’t spend time in solitude, you don’t have either profundity or understanding––you’ve just carried on somebody else’s tradition.

“The hermit tradition is like graduate school––under-graduate school is the monastery––you should go through the first to get to the second.”

“The hermit tradition plays into the Chinese attraction to anarchism,” he says. “If I could choose one word to describe the Chinese character it would be anarchism––hey, don’t respect authority unless it comes with power. It’s very Chinese to want to set up your own shop––the opposite of the Japanese. They’re very much like the cowboy. They respect people who are on their own, but to do that you have to be completely confident in what you’re doing.”

______________

After the hermit book, Red Pine began translating a series of classic Zen texts. In 1995, he published Guide To Capturing A Plum Blossom, an ingenious picture-prose inventory of perception; in 1996, Lao-tzu’s Tao Te Ching; in 2001, The Diamond Sutra; in 2004, The Heart Sutra; and soon he will publish The Lankavatara Sutra.

“The Plum Blossom is the oldest art book ever printed,” he says. “It has an amazing concept of picturing and describing a plum blossom from so many points of view––like in deconstruction, it takes it apart--and it’s important in terms of its cultural connection and what it says about the Chinese spirit.” The Tao Te Ching, although known worldwide as a central text in Chinese philosophy, is only part of the Taoist world view, Red Pine says.

He doubts that Taoism has had a major influence on Buddhism or Zen. “All the early Chinese Buddhist disciples were not necessarily Taoists,” he says. “They were mostly Confucian. I think Confucianism has had a much greater role to play. Taoism itself is a religion that calls on people to become one with the Tao––it’s a religion that focuses on the dialectic of the yin and yang, whereas, at the core, Buddhism is non-dual. Its interest is in transcending duality.

“The Taoist concept of emptiness is totally different from Buddhist emptiness. Taoists are interested in the creation of an immortal spirit body that becomes one with the Tao––you have to do something––it entails doing something, but in Buddhism you have to not do something. It’s always been a current that’s run through Taoism. Every master has his own take on what the Tao is. Lao-tzu’s Tao was ethical, moral Taoism––about what to do in this life, not about the abstract state of how to become successful. And Lao-tzu’s Taoism is a very different Taoism than Chuang-tzu’s.”

Red Pine started translating the Diamond Sutra in 1999, shortly after he began teaching Buddhism and Taoism in exchange for room and board at The City of 10,000 Buddhas near Ukiah, California. He lived there two years before returning to Port Townsend.

“I had tried to translate the Diamond Sutra before, but it still didn’t make sense to me as a coherent whole,” he says. “But when I was in Taiwan I ran into this grammatical study of the Sanskrit in Chinese, and I saw things I’d never seen before––it all seemed to fit together. I based my translation on the Sanskrit text, but translated a lot of the commentaries from the Chinese masters.

“I always give sutras the benefit of the doubt and assume they were spoken by the Buddha. It [the Diamond Sutra] couldn’t have occurred at the beginning of the Buddha’s enlightenment. It was maybe when he was around 60 to 65 years old. Most people assume the Buddha’s teaching is about emptiness where the Diamond Sutra is just about the opposite of that. Most of the Perfection of Wisdom texts take this point of view, whereas the Diamond Sutra takes the opposite point of view. I sort of think the Buddha was thinking that day that maybe a lot of people are getting attached to emptiness, so today I’m going to teach everything is a body, but everything is also a part of the body of Buddha.”

“This is a very big body––but the Buddha is trying to teach people that through the body of the Buddha you gain a great body of merit and that will be your body and this body is also no different than the body the Buddha gained when he became enlightened. But that body itself can become an attachment if you don’t get beyond that. All of it is based on the idea that the quickest way to practice is about giving, about being compassionate.” A highlight of the sutra’s commentaries are the words of Te-ching (Han Shan Te-ching, not to be confused with Han Shan aka Cold Mountain).

“He’s not widely known or translated in the West,” Red Pine says. “But all the Chinese put him on a pedestal. I used his commentaries on the Tao Te Ching and the Diamond Sutra. He certainly ranks as an equivalent to Hui-neng. I always turn to him first. He was fearless and very unique in his insights.”

____________

Under his given name Red Pine, Bill Porter has become the eminence grise of translators and commentators on Zen and Taoist poetry and texts. However, he’s now also something more. In his two travel books, he has stepped out from the shadow of the translator to become himself; in the first, Road to Heaven, he searched out the Taoist hermits in the Chang An mountains, and in his most recent travel book, Zen Baggage, he chronicled the past and the present life of the monasteries of the Chinese Zen patriarchs. The hermit book was a revelation to Westerners and seems to have fascinated many Chinese as well: the Chinese translation of the book is now in its sixth printing under the title Hidden Orchids of Deserted Valleys.

Porter’s personality comes through most vividly in Zen Baggage, which offers generous sketches of his life in Taiwan, his frequent travels to China, and, most revealingly, his on-the-road manners and methods during his six-week, 2,500-mile, templehopping pilgrimage, which was largely a catch-up journey to supplement his many previous visits. He was already on intimate terms with many of the temple abbots and others that he met with on his trip.

Zen Baggage is soaked in wisdom so subtle it is almost invisible. Three-quarters of the way through, you realize that you’ve absorbed a chronology of the major Chinese Zen patriarchs along with Zen’s distinctive starts and stops that collectively make up its birth, its philosophical debates, its divisions, its flowering in the 6th century, and then its slow decline and diffusion into the larger world. Whether he’s interviewing an abbot at Hui-neng’s old temple or eating sweet cakes at a truck stop, he lashes it all together in details that illuminate the stories, metaphysics, koans, and esoterica of early Zen.

His work to date most closely resembles the books of his mentor John Blofeld (1913-1987), the British writer and translator who helped him during his first translation, Cold Mountain Poems. Porter is using his unique talents as a translator and a writer to bring to life Buddhism’s past and present. Along with his 12 translations, his two travel books are singular achievements that have broken new ground in our understanding of Zen and Taoism in contemporary China. They showcase his two greatest assets: his independence as a scholar and his personal understanding of Taoism and Zen.

In 2004, Red Pine presented a paper on translation at an international conference on Chinese poetry at Simmons College in Boston, in which he takes the reader to the very bottom of the art of language, poetry and translation:

“We live in worlds of linguistic fabrication. Pine trees do not grow with the word ‘pine’ hanging from their branches. Nor does a pine tree ‘welcome’ anyone to its shade. It is we who decide what words to use, and, like Alice, what they mean. And what they mean does not necessarily have anything to do with reality. They are sleights of the mind as well as the hand and the lips. And if we mistake words for reality, they are no longer simply sleights but lies. And yet, if we can see them for what they are, if we can see beyond their deception, they are like so many crows on the wing, disappearing with the setting sun into the trees beyond our home. This is what poetry does. It brings us closer to the truth. Not to the truth, for language wilts in such light, but close enough to feel the heat.”

Finding Zen and Book Contracts in Beijing

by Ian Johnson

http://www.nybooks.com/blogs/nyrblog/2012/may/29/zen-book-contracts-bill-porter-beijing/

Prajnaparamita Hridaya Sutra

The Heart Sutra

Red Pine translation

The Heart Sutra: the Womb of Buddhas. Washington: Shoemaker & Hoard, 2004.

The noble Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva,

while practicing the deep practice of Prajnaparamita,

looked upon the five skandhas

and seeing they were empty of self-existence,

said, “Here, Shariputra,

form is emptiness, emptiness is form;

emptiness is not separate from form, form is not separate from emptiness;

whatever is form is emptiness, whatever is emptiness is form.

The same holds for sensation and perception, memory and consciousness.

Here, Shariputra, all dharmas are defined by emptiness

not birth or destruction, purity or defilement, completeness or deficiency.

Therefore, Shariputra, in emptiness there is no form,

no sensation, no perception, no memory and no consciousness;

no eye, no ear, no nose, no tongue, no body and no mind;

no shape, no sound, no smell, no taste, no feeling and no thought;

no element of perception, from eye to conceptual consciousness;

no causal link, from ignorance to old age and death,

and no end of causal link, from ignorance to old age and death;

no suffering, no source, no relief, no path;

no knowledge, no attainment and no non-attainment.

Therefore, Shariputra, without attainment,

bodhisattvas take refuge in Prajnaparamita

and live without walls of the mind.

Without walls of the mind and thus without fears,

they see through delusions and finally nirvana.

All buddhas past, present and future

also take refuge in Prajnaparamita

and realize unexcelled, perfect enlightenment.

You should therefore know the great mantra of Prajnaparamita,

the mantra of great magic,

the unexcelled mantra,

the mantra equal to the unequalled,

which heals all suffering and is true, not false,

the mantra in Prajnaparamita spoken thus:

“Gate, gate, paragate, parasangate, bodhi svaha.”