ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

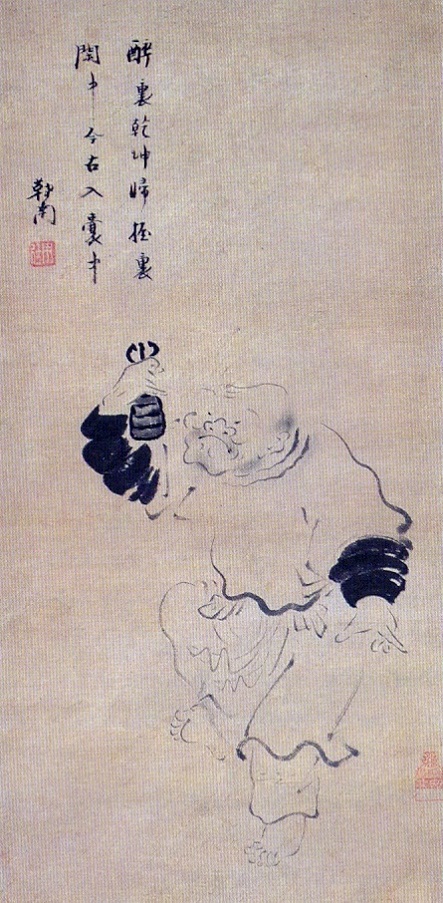

鎮州普化 Zhenzhou Puhua (770-840 or 860)

(Rōmaji:) Chinshū Fuke

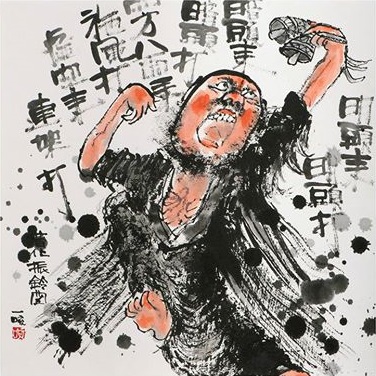

Fuke ringing his bell

by 松花堂昭乗 Shōkadō Shōjō (1584-1639)

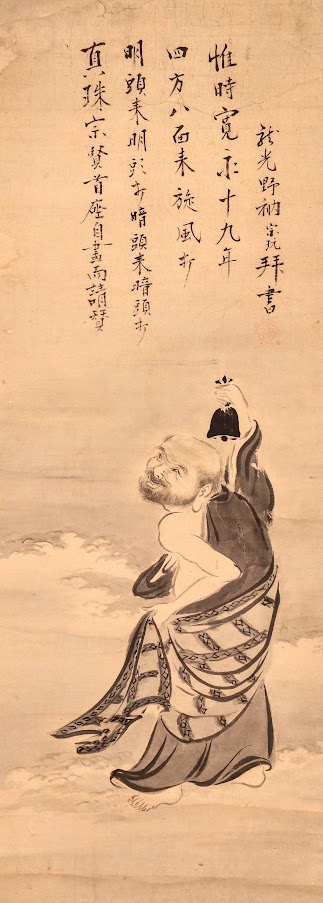

Fuke ringing his bell

by 江月宗玩 Kōgetsu Sōgan (1574-1643)

龍光野衲宗玩拝書

惟時寛永十九年

四方八面來旋風打

明頭來明頭打暗頭來暗頭打

真珠賢首座自書而請賛

"The countryside monk of Ryōkō(in), Sōgan wrote it among his prayers

In the 19th Year of Kan'ei (1642)

If it comes from all directions, it is the whirlwind

If bright comes, it is the bright (morning), if dark comes, it is the dark (night)

The pearl kindly waits for somebody's esteemed written praise."

Translated by I. Nagy

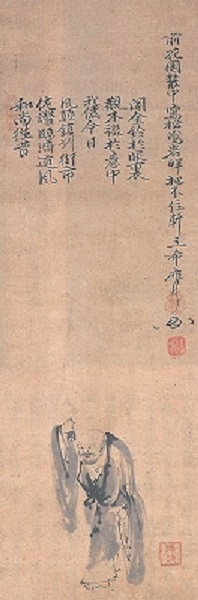

Fuke ringing his bell

by 雪村周继 Sesson Shukei (1504-1589)

An itinerant priest of the Tang dynasty depicted in paintings as wandering the streets of Zhenzhou 鎮州 in a state of feigned or near madness while ringing a bell. Little is known of Puhua's place of birth or background, but he is said to have achieved sudden enlightenment upon hearing the ringing of a bell. Even after his death, probably in the mid-9c, legend claims that the residents of Zhenzhou could still hear Puhua's bell. Puhua's dialogues with the Zen patriarch Linji (Jp: Rinzai 臨済) are recorded in Linjilu (Jp: RINZAIROKU 臨済禄; The Records of Linji) and other sources. Puhua is credited with founding one sect of Zen Buddhism which, at least in later times, believed in playing the bamboo clarinet shakuhachi 尺八 as a spiritual discipline. Supposedly Puhua's chanting led to the creation of the shakuhachi piece kyotaku 虚鐸 or empty bell, and this association with the shakuhachi may have contributed to his popularity as a painting subject in Japan. Extant paintings of Puhua include works by the Southern Song artists Liang Kai (Jp: Ryou Kai 梁楷, act.1201-4) and Muqi (Jp: Mokkei 牧谿, late 13c) as well as ink monochrome works by Japanese artists of the Muromachi and Momoyama periods, including Shoukadou Shoujou 松花堂昭乗 (1584-1634).

普化振鈴図 伝梁楷筆

Puhua Ringing a Bell, attributed to Liang Kai, Nomura Art Museum, Kyoto, Japan

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Puhua_Ringing_a_Bell_attributed_to_Liang_Kai_(Nomura_Art_Museum).jpg

Fuke Zenji by 瀬田掃部 (正忠) Kamon (Masatada) Seta (1548?-1595)

with comments by 雲居希膺 Unkyo Kiyo (1582-1659), Sakata, Yamagata, Japan

紙本墨画普化禅師像 瀬田掃部筆 雲居禅師賛

Puhua

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Puhua

Zhenzhou Puhua (Chinese: traditional: 鎮州普化, simplified: 普化, pinyin: Zhenzhou Pǔhuà; Japanese: Jinshu Fuke, honorifically Fuke Zenji (lit. "Zen master Fuke")—allegedly ca. 770-840 or 860), also called P'u-k'o, and best known by his Japanese name, Fuke, was a potentially mythical Chinese Chán (Zen) master, monk-priest, wanderer and eccentric, whose existence and many affairs were advanced and likely fabricated by the now defunct Fuke Zen or Hotto-ha sect, or sub-sect, of Japanese Rinzai Zen Buddhism in the 17th or 18th century with the publication of the later-disconfirmed document, the Kyotaku Denki (虚鐸伝記), probably first published around 1640. For the komusō (虚無僧) monks of the Fuke sect, he was considered the traditional antecedent—at least in spiritual or philosophical terms—of their order, which was formally established in Edo Japan. It is more likely that the ideological roots of the sect derived from the Rinzai poet and iconoclast Ikkyū and the monk Shinchi Kakushin (心地覺心) who traveled to and from China and Japan in the 13th century. Still according to some accounts the sect is simply a more direct derivative of the Rinzai school and its teachings.

The few records of Puhua's life and affairs are those accounted, if only briefly, in several East Asian religious or historical references. One of the only credible sources on his life is to be found in the Tang Dynasty Record of Linji, wherein he is portrayed as an obscure student and eventual dharma heir of Panshan Baoji, as well as a friend, colleague, student and/or contemporary of Linji Yixuan, who founded the Linji (臨済宗 Rinzai) sect in China. This implies that he may have been a real individual, although the legends surrounding him in the Kyotaku Denki which connect him to the Fuke sect have been proven as fabrications created to further the komusōs' benefits under the Tokugawa shogunate.

The legends surrounding Puhua were more recently mentioned in the Monumenta Nipponica, R.H. Blyth's A History of Haiku (published in 1963) as well as some of the writings of Osho, along with later publications concerning the Fuke-shū, the shakuhachi and related topics. In 1988 a shakuhachi learning and playing manual co-authored by the shakuhachi performer Christopher Yohmei Blasdel and the scholar Kamisango Yūkō was published; the work is entitled The Shakuhachi: A Manual for Learning (ISBN 978-1933606156), and thoroughly details the historicity of Fuke/Puhua and the precursors to Fuke Zen in China.

Sources for the life of Puhua

There are two main sources for the life of Puhua: the aforementioned Linji lu or Record of Linji from China and the Kyotaku Denki Kokuji Kai from Japan. The latter has been debunked as mostly false, however the Linji lu, conversely, is known to contain a variety of historically-accurate documents regarding Chinese Chán and is perhaps one of the most important works on Zen Buddhism. Thus, if Puhua actually existed his life would best be known by way of the Record of Linji.

While there is much disparity between the two texts, they do agree on at least one issue: In both the Record and Kyotaku Denki the notion of Puhua being an eccentric imbued with a sort of crazy wisdom, and perhaps even an iconoclast, is supported. Yet the texts again diverge on the issue of Fuke's influence on the Fuke sect of Japan: While the Kyotaku Denki directly attributes the founding of the school to him, the Fuke sect did not exist in China and as such he is never mentioned to be the leader of a separate religious tradition in the Linji lu. Although this is the case, the Record does provide certain subtleties regarding Puhua as being a person of his own, self-directed character who often did things ubiquitously and ignored social norms and doctrinal establishments.

The following account of Puhua's life is an amalgamation of the accounts featured in both the Record and Kyotaku Denki, although it includes some outside references as well.

Historical accounts

Puhua is said to have been born in Tang Dynasty China in the year 770. It is not known where he was born, however his name, Zhenzhou, possibly references Zhengzhou, a city in the modern Henan province of north-central China. The Kyotaku Denki states that he lived in "Chen Province". Coincidentally, there is a village known as Chen by the Yellow River in Henan. Furthermore, one of Puhua's supposed students, Chang Po (Japanese: Chōhaku; also stylized Cho Haku, Chohaku or Chō Haku and sometimes referred to as, simply, Haku) is said to have lived in Henan (also transliterated as Ho Nan).

One account states that Puhua lived in and traveled through an area known as "Toh" in China.

In the Record of Linji Puhua is noted as being a student and dharma heir of Panshan Baoji (who by some accounts is either the same person as, or different from, another Chán patriarch by the name of Baizhang Huaihai) alongside two other dharma heirs: Huangbo and Linji. Puhua's own group of students reportedly included several individuals whose historicity is also dubious: "Ennin", "Chang Po" (Chōhaku) and "Zhang Bai" (whose name is also stylized as Zhang Bo). (At least one, if not all of these individuals is implied to have been Puhua's heir and purportedly passed on his legacy to many more disciples and eventually the komusō.)

Puhua is said to have been not only a contemporary of Linji/Rinzai, but also one of his students. Thus Puhua is sometimes included in the fold of the Linji zōng (Japanese: Rinzai-shū) in certain chronicles, as well as Huineng's "Sudden Enlightenment" school because it is, in some respects, an antecedent for the Rinzai school to begin with, and especially influenced Linji's epoynmous sect in the Tang Dynasty, where and when Puhua and Linji lived. (Not surprisingly, the Japanese Fuke sect of the Edo period considered itself a delineation of the Rinzai sect.)

Fuke was reputedly a multi-talented monk and priest, known for being inventive, intelligent and at the same time quite strict. He is characterized by all accounts to have been a spontaneous individual who demonstrated a unique style of non-verbal communication that is an important aspect of Zen Buddhist philosophy and historically the staple teaching method of the Zen Patriarchs and even Bodhidharma (an Indian monk and the ostensible founder of Zen Buddhism) himself. The Kyotaku Denki reinforces this characteristic, stating that Puhua "was pleased with his uninhibited Zen spirit."

This kind of capriciousness can be gleaned from a legend regarding Puhua wherein he is attending the deathbed of his master Panshan:

When Panshan Baoji was near death, he said to the monks, "Is there anyone among you who can draw my likeness?"

Many of the monks made drawings for Panshan, but none were to his liking.

The monk Puhua stepped forward and said, "I can draw it."

Panshan said, "Why don't you show it to me?"

Puhua then turned a somersault and went out.

Panshan said, "Someday, that fellow will teach others in a crazy manner!"

Having said these words, Panshan passed away.

Many stories about Puhua that appear in the Record of Linji add to his reputation of having a rough and uncompromising manner of expressing the dharma. For example:

44.a. One day the master (Linji Yixuan) and Puhua went to a vegetarian banquet given them by a believer. During it, the master asked Puhua: "'A hair swallows the vast ocean, a mustard seed contains Mt. Sumeru' – does this happen by means of supernatural powers, or is the whole body (substance, essence) like this?" Puhua kicked over the table. The master said: "Rough fellow." Puhua retorted: "What place is this here to speak of rough and refined?"

b. The next day, they went again to a vegetarian banquet. During it, the master asked: "Today's fare, how does it compare with yesterday's?" Puhua (as before) kicked over the table. The master said: "Understand it you do – but still, you are a rough fellow." Puhua replied: "Blind fellow, does one preach of any roughness or finesse in the Buddha-Dharma?" The master stuck out his tongue.

There is some controversy as to the degree and nature of Fuke's musical talents, but his later "followers" (the monks of the Fuke sect in Japan) would often reflect on a certain story that appears in the Kyotaku Denki for inspiration.

The story tells of Puhua going through his hometown, ringing a bell and reciting a gatha to summon others to enlightenment. The same, for many Fuke practitioners, applied to the shakuhachi through suizen (Japanese: 吹禅)—"blowing meditation" traditionally practiced by the komusō involving the use of the shakuhachi as a spiritual/religious instrument for meditation and as a way to attain bodhi—and its mastery was seen as a path to enlightenment:

Ringing a taku , he would go to town and say to passersby: "Myōtōrai myōtōda, antōrai antōda, Shihō hachimenrai (ya), senpūda, Kokūra[i] (ya), rengada. [This roughly translates to,] "If attacked in the light, I will strike back in the light. If attacked in the dark, I will strike in the dark. If attacked from all quarters, I will strike as a whirlwind does. If attacked from the empty sky, I will thrash with a flail."

One day, a man named Chō Haku of Ho Nan province heard these words and revered the priest Fuke for his great virtue. He appealed to the priest for permission to follow him, but the priest did not accept him.

Haku had previously had a taste for playing pipes. Having listened to the sound of the Priest's bell, he at once made a [bamboo] flute and imitated the sound. [Thereafter] he played the sound untiringly on the flute and never played other pieces

Since he made the sound of the bell on his flute, he named the flute kyotaku...

(The term kyotaku means "empty bell" in Japanese. "Empty bell" can also be translated as Kyorei, which happens to be the name of one of the san koten honkyoku (Japanese: "three classic original pieces"; also known as the Bekkaku), honkyoku (Japanese: 本曲, "original pieces") being the traditional musical pieces for shakuhachi played by the mendicant monks of the Fuke sect for alms and enlightenment since as early as the 13th century, long before the Fuke sect was actually formally established.)

Fuke's gatha is sometimes called "Shidanoge".

Another version of the story portrays Chō Haku attempting to become the student of Zhang Bai instead of Puhua directly, as in this version Zhang Bai is depicted as a student who garnered favor from Puhua and so had become admired by Chō Haku.

It was believed by the historical komusō that the tradition that led to suizen was handed down by Chō Haku through his family and eventually reached its way to Japan by way of the monk Kakushin, to the komusō and later the founder of Myoanji—at one time the head temple of the Fuke-shū in Kyoto and still a place of profound importance for many shakuhachi, Fuke Zen and Rinzai Zen enthusiasts the world over—Kyochiku Zenji (also known as Kichiku).

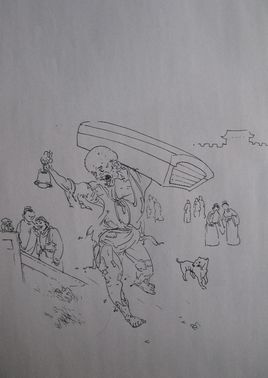

Death

Fuke's death is related as follows:

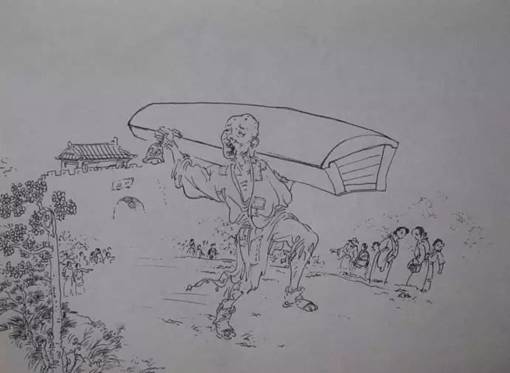

Painting by 金森一咳 Kanamori Ichigai (born Osaka 1941)"One day at the street market Fuke was begging all and sundry to give him a robe. Everybody offered him one, but he did not want any of them. The master [Linji] made the superior buy a coffin, and when Fuke returned, said to him: "There, I had this robe made for you." Fuke shouldered the coffin, and went back to the street market, calling loudly: "Rinzai had this robe made for me! I am off to the East Gate to enter transformation" (to die)." The people of the market crowded after him, eager to look. Fuke said: "No, not today. Tomorrow, I shall go to the South Gate to enter transformation." And so for three days. Nobody believed it any longer. On the fourth day, and now without any spectators, Fuke went alone outside the city walls, and laid himself into the coffin. He asked a traveler who chanced by to nail down the lid. The news spread at once, and the people of the market rushed there. On opening the coffin, they found that the body had vanished, but from high up in the sky they heard the ring of his hand bell."

Legacy

Hisamatsu Fuyo, a 19th century Zen Buddhist hermit and shakuhachi dai-shihan (grandmaster) was once interviewed regarding Fuke:

Q. "What kind of person was Fuke Zenji?"

A. "I do not know. Better ask someone with more knowledge of Zen."

Q. "Wasn't Fuke the ancestor of shakuhachi? If one follows this path but doesn't know its origins, is that not a sign of immaturity?"

A. "As for myself, because I understand the source of shakuhachi, I say I do not know Fuke. Fuke was an enlightened man, but I do not think he sought his enlightenment by playing shakuhachi. He cannot be compared to an ignorant blind person like me who plays shakuhachi because he enjoys it and has gradually come to know that shakuhachi is a Zen instrument. Even if Fuke had played shakuhachi, it would only have been a passing fancy. His practice of shakuhachi would not compare to my training for many years. If Fuke were to come alive again in this generation he would surely become my disciple and ask me to show him the way. If you look at records from the time of Fuke, and if you know all about his life, but you do not know his enlightenment, then you do not know Fuke. On the other hand, a person who knows nothing of his life, but knows his enlightenment, he knows Fuke. I do not know him yet."

普化振鈴図 Fuke's Bell, 1988, 79cm × 56cm

Painting by 金森一咳 Kanamori Ichigai (born Osaka 1941)

Puhua & Linji

The Record of Linji. Translation and commentary by Ruth Fuller Sasaki. Ed. by Thomas Yūhō 釈雄峯 Kirchner. University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, Bilingual edition, 2009.

Zhenzhou Puhua 鎮州普化 (d. 860), was a disciple of Panshan Baoji 盤山寶積 (n.d.)

of Youzhou 幽州; Baoji, in turn, was an heir of Mazu. Very little is known of his life.

The biographical accounts found in zj 17, the jc (t 51: 280b–c), and the sg (t 50: 837b)

consist of little more than the anecdotes featuring Puhua in the Critical Examinations

section of the ll. In Japan, Puhua (Jap. Fuke) is honored as the patriarch of the Fuke

school 普化宗, a subordinate and now defunct order of the Zen school. Its adherents

(known as komusō 虛無僧) led itinerant lives and played bamboo flutes called shakuhachi

尺八, the music of which was considered an aid to enlightenment. Japanese tradition

holds that the school was founded aft er Puhua’s death by his lay disciple Zhang Bai 張伯

(n.d.) of Henan. The Fuke school was introduced to Japan by the Japanese Zen monk

Shinchi Kakushin on his return from China in 1254.

勘辨 Critical Examinations

03 師、 一日同普化、赴施主家齋次、師問、毛吞巨海、芥納須彌。爲是神通妙用、本體如然。普化踏倒飯床。師云、太麁生。普化云、這裏是什麼所在、說麁說細。師來 日、又同普化赴齋。問、今日供養、何似昨日。普化依前踏倒飯床。師云、得即得、太麁生。普化云、瞎漢、佛法說什麼麁細。師乃吐舌。

One day when the master and Puhua were attending a dinner at a patron's house, the master asked, “‘A hair swallows up the great sea and a mustard seed contains Mount Sumeru.' Is this the marvelous activity of supernatural power or is it original substance as it is?” Puhua kicked over the dinner table.“How coarse!” exclaimed the master.

“What place do you think this is—talking about coarse and fine!” said Puhua.

The next day the master and Puhua again attended a dinner. The master asked, “How does today's feast compare with yesterday's?” Puhua kicked over the dinner table as before. “Good enough,” said the master, “but how coarse!”

“Blind man!” said Puhua. “What's buddhadharma got to do with coarse and fine?”

The master stuck out his tongue.

04 師 一日、與河陽木塔長老、同在僧堂地爐內坐。因說、普化每日在街市、掣風掣顛。知他是凡是聖。言猶未了、普化入來。師便問、汝是凡是聖。普化云、汝且道、我 是凡是聖。師便喝。普化以手指云、河陽新婦子、木塔老婆禪。臨濟小厮兒、卻具一隻眼。師云、這賊。普化云賊賊、便出去。

One day when the master and the venerable old priests Heyang and Muta were sitting together around the fire-pit in the Monks' Hall, the master said, “Every day Puhua goes through the streets acting like a lunatic. Who knows whether he's an ordinary person or a sage?” Before he had finished speaking Puhua came in. “Are you a commoner or a sage?” the master asked.

“Now, you tell me whether I'm a commoner or a sage,” answered Puhua. The master shouted. Pointing his finger at them, Puhua said, “Heyang is a new bride, Muta is a Chan granny, and Linji is a young menial, but he has the eye.”

“You thief!”cried the master.

“Thief, thief!”cried Puhua, and went out.

05 一日、普化在僧堂前、喫生菜。師見云、大似一頭驢。普化便作驢鳴。師云、這賊。普化云賊賊、便出去。

One day Puhua was eating raw vegetables in front of the Monks' Hall. The master saw him and said, “Just like an ass!”

“Heehaw, heehaw!” brayed Puhua.

“You thief!” said the master.

“Thief, thief!” cried Puhua, and went off.

06 因普化、常於街市搖鈴云、明頭來、明頭打、暗頭來、暗頭打、四方八面來、旋風打、虛空來、連架打。師令侍者去、纔見如是道、便把住云、總不與麼來時如何。普化托開云、來日大悲院裏有齋。侍者回、擧似師。師云、我從來疑著這漢。

Puhua was always going around the streets ringing a little bell and calling out:

Coming as brightness, I hit the brightness;

Coming as darkness, I hit the darkness;

Coming from the four quarters and eight directions, I hit like a whirlwind;

Coming from empty sky, I lash like a fl ail.

The master told his attendant to go and, the moment he heard Puhua say these words, to grab him and ask, “If coming is not at all thus, what then?”

[The attendant went and did so.]

Puhua pushed him away, saying, “There'll be a feast tomorrow at Dabei yuan.”

The attendant returned and told this to the master. The master said, “I've always held wonder for that fellow.”

08 師 爲黃檗馳書去潙山。時仰山作知客。接得書、便問、這箇是黃檗底、那箇是專使底。師便掌。仰山約住云、老兄知是般事、便休。同去見潙山。潙山便問、黃檗師兄 多少衆。師云、七百衆。潙山云、什麼人爲導首。師云、適來已達書了也。師卻問潙山、和尚此間多少衆。潙山云、一千五百衆。師云、太多生。潙山云、黃檗師兄 亦不少。師辭潙山。仰山送出云、汝向後北去、有箇住處。師云、豈有與麼事。仰山云、但去、已後有一人佐輔老兄在。此人祇是有頭無尾、有始無終。師後到鎮 州、普化已在彼中。師出世、普化佐賛於師。師住未久、普化全身脫去。

Linji went to Guishan bearing a letter from Huangbo. Yangshan, who at that time was in charge of receiving guests, took the letter and said, “This is Huangbo's; where's the messenger's?”

Linji slapped at him.

Yangshan seized Linji and said, “Brother, since you know this much, that's enough.” Then they went together to see Guishan.

Guishan asked, “How many students has my brother Huangbo?”

“Seven hundred,” answered Linji.

“Who is their leader?”asked Guishan.

“He has just delivered a letter to you,” replied Linji. Then Linji, in his turn, asked Guishan, “Venerable Priest, how many students do you have here?”

“Fifteen hundred,” answered Guishan.

“That's a lot!”said Linji.

“My brother Huangbo also has no small number,” said Guishan.

Linji took his leave of Guishan. As Yangshan was seeing him off, he said “Later on you'll go to the north and there'll be a place for you to stay.”

“How can that be?” said Linji.

“Just go,” replied Yangshan. “Afterwards there'll be a man to help you, my venerable brother. He'll have a head but no tail, a beginning but no end.”

Later Linji arrived in Zhenzhou; Puhua was already there. When Linji became head of a temple, Puhua was of help to him. But the master had not been there very long when Puhua just vanished, body and all.

24 普 化一日、於街市中、就人乞直裰。人皆與之。普化倶不要。師令院主買棺一具。普化歸來。師云、我與汝做得箇直裰了也。普化便自擔去、繞街市叫云、臨濟與我做 直裰了也。我往東門遷化去。市人競隨看之。普化云、我今日未、來日往南門遷化去。如是三日、人皆不信。至第四日、無人隨看。獨出城外、自入棺內、倩路行人 釘之。即時傳布。市人競往開棺、乃見全身脫去。祇聞空中鈴響、隱隱而去。

One day Puhua went about the streets asking people he met for a onepiece gown. They all offered him one, but Puhua declined them all.

Linji had the steward of the temple buy a coffin, and when Puhua came back the master said, “I've fixed up a one-piece gown for you.”

Puhua put the coffin on his shoulders and went around the streets calling out, “Linji fixed me up a one-piece gown. I'm going to the East Gate to depart this life.” All the townspeople scrambled after him to watch.

“No, not today,” said Puhua, “but tomorrow I'll go to the South Gate to depart this life.”

After he had done the same thing for three days no one believed him anymore.

On the fourth day not a single person followed him to watch. He went outside the town walls all by himself, got into the coffin, and asked a passerby to nail it up. The news immediately got about. The townspeople all came scrambling; upon opening the coffin, they saw he had vanished, body and all.

Only the sound of his bell could be heard in the sky, receding away: tinkle...tinkle... tinkle....

行錄 Record of Pilgrimages

22 師 諱義玄、曹州南華人也。俗姓邢氏。幼而頴異、長以孝聞。及落髮受具、居於講肆、精究毘尼、博賾經論。俄而歎曰、此濟世之醫方也、非敎外別傳之旨。即更衣游 方、首參黃檗、次謁大愚。其機緣語句、載于行錄。既受黃檗印可、尋抵河北。鎮州城東南隅、臨滹沱河側、小院住持。其臨濟因地得名。時普化先在彼、佯狂混 衆、聖凡莫測。師至即佐之。師正旺化、普化全身脫去。乃符仰山小釋迦之懸記也。適丁兵革、師即棄去。太尉默君和、於城中捨宅爲寺、亦以臨濟爲額、迎師居 焉。後拂衣南邁、至河府。府主王常侍、延以師禮。住未幾、即來大名府興化寺、居于東堂。師無疾、忽一日攝衣據坐、與三聖問答畢、寂然而逝。時唐咸通八年丁 亥、孟陬月十日也。門人以師全身、建塔于大名府西北隅。勅謚慧照禪師、塔號澄靈。合掌稽首、記師大略。

The master's name as a monk was Yixuan. He was a native of the prefecture of Nanhua in the province of Cao. His family name was Xing. As a child he was exceptionally brilliant, and when he became older he was known for his filial piety. After shaving his head and receiving the full precepts, he frequented lecture halls; he mastered the vinaya and made a thorough study of the sutras and śāstras.

Suddenly [one day] he said with a sigh, “These are prescriptions for helping the world, not the principle of the transmission outside the scriptures.”

Then he changed his robe and traveled on a pilgrimage. First he studied under Huangbo. Then he visited Dayu. What was said on those occasions has been set down in the “Record of Pilgrimages.”

After receiving the seal of dharma from Huangbo, the master went to Hebei and became priest of a small temple on the banks of the Hutuo River, outside the southeast corner of the capital of Zhenzhou. Because of its location the temple was called “Linji” (“Overlooking the Ford”). By that time Puhua was already there. Pretending to be crazy, Puhua mixed with the people and no one could tell whether he was a sage or a commoner. When the master arrived there Puhua was of help to him. When the master's teaching began to flourish, Puhua vanished, body and all. This agreed with the prediction made by Yangshan, the “Little Śākya.”

It happened that local fighting broke out, and Linji abandoned the temple.The Grand Marshal, Mo Junhe, donated his house inside the town walls and made it into a temple. Hanging up a plaque there, inscribed with the old name “Linji,” he had the master make it his residence.

Later the master tucked up his robes and went south to the prefecture of He. The governor of the prefecture, Councilor Wang, extended to him the honors due a master. After staying for a short while, the master went to Xinghua temple in Daming Prefecture, where he lived in the Eastern Hall.

Suddenly one day the master, although not ill, adjusted his robes, sat erect, and when his exchange with Sansheng was finished, quietly passed away. It was on the tenth day of the first month in the eighth year of Xiantong of the Tang dynasty. His disciples built a memorial tower for the master's body in the northwest corner of the capital of Daming Prefecture. The emperor decreed that the master be given the posthumous title Meditation Master Huizhao [“Illuminating Wisdom”] and his stupa be called Chengling [“Translucent Spirit”]. Joining my hands with palms together and bowing low my head, I have recorded in summary the life of the master.

![]()

金森一咳 Kanamori Ichigai (born Osaka 1941): Pu-hua rázza csengőjét

Pu-hua példázatok

Jen-csao és Cun-csiang: Feljegyzések Lin-csiről (Lin-csi Lu) c. kötetből

[Válogatás Miklós Pál fordításában]

In: Kapujanincs átjáró: Kínai csan-buddhista példázatok, Vál., kínaiból ford., a jegyzeteket és az utószót írta Miklós Pál, a fordítást az eredetivel Csongor Barnabás vetette egybe, Budapest, Helikon Kiadó, 1987, Prométheusz Könyvek 16; ua.: 2., változatlan kiad., Budapest, Helikon, 1994. 25-28, 145. oldal

44.

Egy napon, amikor Pu-huával együtt a kolostor egyik jó-

tevőjéhez voltak hivatalosak böjti vacsorára, a Mester ezt

a kérdést tette föl:

– „Egyetlen hajszál (81) fölszippantja az óceánt, egyetlen

szem mustármag elnyeli a Szuméru-hegyet” – ez vajon a

természetfölötti tudás csodálatos hatása, vagy csupán az

eredendő, természetes lényegtől van?

Pu-hua egyetlen rúgással fölborította az étkezőzsá-

molyt. A Mester azt dörmögte:

– Faragatlan fickó!

Mire Pu-hua:

– Épp ez az a hely, ahol faragatlanságról vagy finomság-

ról (82) kell értekezni?

Másnap a Mester ismét oda ment vacsorára Pu-huával.

Azt kérdezte:

– A tegnapihoz hasonlítva, milyen az, amit ma tálalnak

nekünk?

Pu-hua újra fölrúgta az étkezőzsámolyt.

A Mester szólt:

– Ejnye, ejnye, faragatlan fickó!

Pu-hua nem hagyta annyiban:

– Vaksi fajzat! Hol esik szó a buddhista Törvényben fa-

ragatlanságról és finomságról?

A Mester ekkor nyelvet öltött rá. (83)45.

Egyszer a Mester együtt üldögélt a szerzetesek csarnoká-

ban a lábmelegítőn, két öregebbel, Ho-janggaI és Mu-

tával. (84) Így szólt: – Pu-hua mindennap az utcákon és a

piacon bolondozik. Ki tudja, közönséges ember-e vagy

szent?

Alig fejezte be, amikor belépett Pu-hua. A Mester ek-

kor hozzá magához intézte a kérdést:

– Közönséges vagy te, vagy szent?

Pu-hua feleselt:

– Mondd meg te, hogy közönséges vagyok-e vagy szent?

A Mester khát horkantott. Pu-hua ekkor, sorban rájuk

mutatva, így kiáltott: – Ho-jang, a fiatal menyecske, (85) Mu-

ta, az ő nénikés (86) Csan-jával és Lin-csi, a kisinas – de hár-

muknak csak félszemük van!

A Mester fortyogott:

– Ez a lator!

Pu-hua kirohant, kiáltozva:

– Fogják meg! Lator!46.

Egyik napon Pu-hua a szerzetesek csarnoka előtt üldö-

gélt és nyers káposztát falt. A Mester meglátta és rá-

szólt:

– Egészen olyan vagy, mint egy szamár!

Erre Pu-hua elkezdett torkaszakadtából iázni. A Mester

rászólt:

– Te, lator!

Pu-hua kiáltozva szaladt el:

– Fogják meg! Lator!47.

Pu-hua állandóan az utcákat és a piacot rótta, egy csengőt

rázott, és mondogatta:Annak, aki sötétben jő, (87) a sötétben rázom,

Annak, aki világosban, világosban rázom,

Annak, aki négy égtájról, annak forgószéllel,

Annak, aki magas űrből, annak hadaróval.A Mester nyomába küldte egyik novíciusát. Ez tapasz-

talta, hogy Pu-hua valóban úgy tesz, amint híresztelik, s

nyomban fülön fogta:

– És azzal, aki se nem így, se nem úgy jő, mit csinálsz?

Pu-hua kiszabadította magát, és így felelt:

– Lesz holnap egy szerény kis vacsora a Nagy Könyörü-

letes kolostorában. (88) – A novicius hazament, és jelentette a

történteket a Mesternek, aki így szólt:

– Mindig is gyanús volt (89) nekem ez a fickó!65.

Egy napon Pu-hua a piacon koldult: mindenkihez azzal

fordult, hogy egy darabból varrott öltözetet adjon neki.

Sokan kínáltak neki ruhákat, de ő egyiket sem fogadta el.

A Mester szólt a kelostor kulcsárjának, hogy vegyenek neki

egy koporsót. Amikor Pu-hua hazajött, a Mester így szólt:

– Csináltattam neked egy darabból varrott öltözetet.

Pu-hua ekkor vállára vette a koporsót, és körbe szaladt

vele a piacon, kiáltozva:

– Lin-csi csináltatott nekem egy darabból varrott ru-

hát! Viszem is a Keleti Kapuhoz, ott lesz az én átváltozá-

som.

A piac népe közül sokan szegődtek a nyomába, kíván-

csiskodva, de Pu-hua igy szólt hozzájuk:

– Nem ma lesz! Holnap megyek a Déli Kapuhoz, ott lesz

az átváltozásom. (90) Így bolonditotta őket három napon ke-

resztül, hogy végül már senki sem hitt neki. A negyedik na-

pon, anélkül hogy bárki is észrevette és köszöntötte volna,

kiment egészen egyedül a falakon kívülre, ott maga má-

szott bele a koporsóba, majd megkért egy arra járót, hogy

szögezze rá a fedelet. A hír azonban nyomban szertefu-

tott, s a piac népe egymást taszigálva rohant oda, hogy fel-

nyissák a koporsót. S látták, hogy eltűnt onnan, levetve

magáról ép testét. (91) Csupán a csengettyűszó hallatszott va-

lahonnan a magasból, s lassan az is elenyészett.

JEGYZETEK

Pu-hua kortársa is, rendtársa is volt Lin-csInek, több is an-

nál: hűséges kisérője s olykor még mintaképe is. Különc vi-

selkedésével hívta fel magára a figyelmet – nevét is egyik

különcségéről kapta: állandóan csengőt rázott egy rigmussal,

hogy mindenkit megtérítsen; a pu-hua kifejezés jelentése:

'általános megtérés', Az alábbi történetek különcségeíről

és mintaszerű haláláról szólnak.81. Egyetlen hajszál . . . – Az indiai és a buddhista filozófia

végtelen kicsiny és végtelen nagy fogalmainak képei.

A Szuméru- vagy Méru-hegy az istenek otthona – tu-

lajdonképpen a „szent hegy” (amelyet aztán 'a hó ott-

hona', azaz Himalája néven konkretizálnak),82. faragatlanságról vagy finomságról . . . – Pu-hua válasza

a jó, mert a Csan, mint már jeleztük, elutasítja az er-

kölcsi különbségtételt.83. nyelvet öltött rá . . . – Lin-csi dorgálása és nyelvöltő-

getése voltaképp dicséret; igen gyakran közli ilyen for-

mában elismerését.84. Ha-jang és Mu-ta – Nevükön kívül semmit sem tudni

róluk.85. fiatal menyecske – Azaz: tapasztalatlan szerzetes, A

szerzetes családot cserél, akár a kínai menyecske: ez

férje családjába, amaz a kolostori közösségbe lép be.86. nénikés – A "jóságos" (mint nénike az unokaöccséhez);

kínai népi metafora.

87. Annak, aki sötétben jó . . . – Homályos értelmű rigmus.88. a Nagy Könyörületes kalostora – Kuan-jin (Avalóki-

tésvara bódhiszattva) tiszteletének szentelt kolostor.89. Mindig is gyanús volt . . . – Voltaképpen ez is dicséret.

A 65. példázat Pu-hua történetének befejező része,

azért került ide:90. átváltozásom – Taoista szóhasználat a halálra.

91. levetve magáról ép testét . . . – Mint a kínai néphit sze-

rint a tücsök, amely leveti "bőrét", de nem pusztul el,

csak átváltozik.