ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

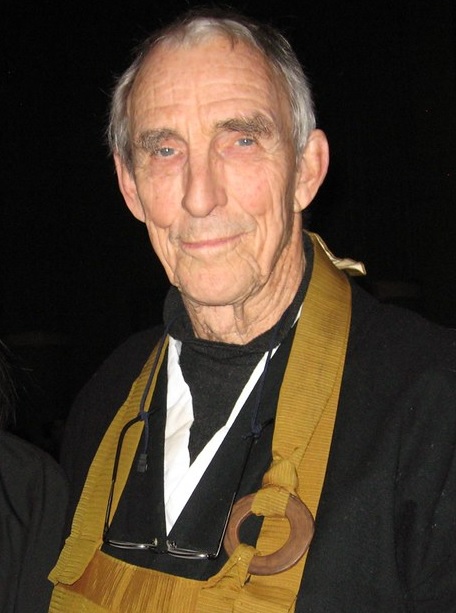

Peter Matthiessen (1927-2014)

Dharma name: 無量 Muryō

Peter Matthiessen (Muryo* roshi) studied Zen with Nakagawa Soen Roshi, Eido Shimano Roshi, Taizan Maezumi Roshi, and received Dharma Transmission from Bernard Tetsugen Glassman Roshi in 1984. He is author of many books, including The Snow Leopard, Nine-Headed Dragon River, and East of Lo Monthang, and is a lifelong environmentalist and worker for social justice.

* 無量 Mu Ryō, “No Limit” or “Boundless,” from the third of the Four Vows:

hōmon muryō seigan gaku—“The Dharma is boundless, I vow to perceive it”

—which I was chanting with Eido-roshi at the moment of my wife's death.

http://zenpeacemakers.org/2014/04/roshi-peter-muryo-matthiessen/ by Bernie Glassman

http://www.lionsroar.com/no-complaints-writer-zen-master-peter-mathiessen-1927-2014/ By Konchog Norbu

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peter_Matthiessen

http://dept.sfcollege.edu/news/daily/pdf/2008/Matthiessen-evening.pdf

PDF: The Snow Leopard (1978)

Dharma Lineage

[...]

梅庵白純 Baian Hakujun (黒田 Kuroda, Maezumi's father, 1898-1978)

佛心大山 Busshin Taizan (1931-1995) [前角博雄 Maezumi Hakuyū]

梅仙徹玄 Baisen Tetsugen (1939-2018) [Bernard Glassman]

無量 Muryō (1927-2014) [Peter Matthiessen]

PDF: Nine-Headed Dragon River: Zen Journals 1969-1982

Shambhala Dragon Editions, Boston, 1986

Contents

Preface

Author’s Note

America: Rinzai Journals 1969–1976

Nepal: Himalayan Journals 1973

Japan: Soto Journals 1976–1982

Appendix Notes Glossary Index

Japan: Soto Journals 1976–1982

Now, mountains, rivers, earth, the sun, moon, and stars are mind. At just this moment, what is it that appears directly in front of you? The sun, moon, and stars as seen by humans are not the same, and the views of various beings differ widely. Likewise the views about one mind differ. Yet these views are nothing but mind. Is it inside or outside? Does it come or go? Does it increase one bit at birth or not? Does it decrease one particle at death or not? . . . All this is merely a moment or two of mind. A moment or two of mind is a moment of mountains, rivers, and earth, or two moments of mountains, rivers and earth. . . .

“Everyday mind” means to maintain an everyday mind in the world of life and the world of death. Yesterday goes forth from this moment, and today comes forth from this place. When it goes the boundless sky goes, when it comes the entire earth comes. . . . This boundless sky and entire earth are like unrecognized words, or the one voice that gushes out of the earth.

Body and Mind Study of the Way

—EIHEI DOGENCHAPTER NINE

ON the day that ended the great inaugural sesshin at Dai Bosatsu, a group of Zen priests led by Sochu-roshi wished to visit the large bronze statue of the Buddha on the farther shore of Beecher Lake, perhaps two hundred yards across the water from the monastery. Instructed to ferry them across, I watched in alarm as buddha after buddha stepped blithely from the little dock into the leaky flat-bottomed rowboat, then remained standing, not simply because of inexperience with boats but because there was no room to sit down. Speaking not a word of Japanese, I waved and motioned with respectful gestures, trying to convey the impossibility of the whole plan.

Cheerfully the roshis waved and motioned back. Being innocent of nautical experience (or privy to miraculous information), they saw no reason why arm-waving, enthusiastic groups of upright and robust Zen masters should not travel in confidence across dark waters in a small, overloaded boat. Impatient with this indecisive student, one waved me on while another attempted to join me on the oarsman’s seat; a third leaned far overboard in a strenuous effort to push the boat free from the dock, to which I clung with straining arms until all at last were squashed onto the seats. At this point the boat was so low in the water that even if some ill-considered motion did not capsize it, the first zephyr of ill wind would bring the lake pouring in over the gunwales. I groaned as yet another buddha, coming down the slope, was greeted with shouts of welcome from the boating party.

This roshi, a handsome man in his early forties, was the Soto teacher from Los Angeles who had participated in Eido-roshi’s shin-san-shiki, or abbot installation, in 1972. Taizan Mae-zumi-roshi1 made no effort to get in the boat, nor did he caution the other roshis to abandon the doomed craft while there was time. Ignoring my signals of distress, he smiled like a sad angel, as if this group was already beyond saving, and nodded his head in the direction of the Buddha statue across the lake. Still I hesitated, and he murmured quietly, “It is all right.” Either he knew something that I did not, or he refused to intervene in the imminent destruction of his Rinzai brothers. “It is all right,” he repeated with implacable serenity, still smiling that sad, beatific smile, as if giving me the Zen instruction, “Do not cling!”

His conviction was impressive, and fired my spirit. Letting go, I set off with small and mindful strokes across the water. Maezumi-roshi stood unmoving on the dock, a guardian spirit, as I transported those buddha-beings to the other shore, then steadied the boat in the mad thrash for camera angles that took place beneath the bronze eye of the Buddha (for even Zen masters, in camera-crazed Japan, are equipped to record the illusory nature of existence). Returned to the dock, they cried out, “Kino doku!” (“Oh, this poisonous feeling!” [of being in your debt]) and “Arigato!” (“Such a difficult matter!”).2 Maezumi-roshi, with a minute bow, turned away and walked back up the hill.

Maezumi-roshi had been preceded to Dai Bosatsu by his two senior monks, Tetsugen and Gempo, who urged me to come and study with him in Los Angeles. The timing was auspicious since I was frequently in California on research related to American Indians. American Indian spirituality seemed so akin to Zen (as well as to Tibetan Buddhism) that in my Himalayan journals I was speculating about ancient common origins, an archaic religion, perhaps, in some formerly fertile heartland such as Soen-roshi’s old haunt in the Gobi Desert.

In mid-January of 1977, on a two-day visit to the Zen Center of Los Angeles, I received a warm welcome from Maezumi-roshi, Tetsugen, and Gempo. The following week I returned to ZCLA for January sesshin. Maezumi-roshi was extremely hospitable, putting me up in his own house, but sesshin itself was disconcerting. Although I enjoyed my outdoor work on the center’s buildings, the long work-practice periods that are customary in Soto temples weakened the intensity of relentless zazen that I had come to depend on in Rinzai practice. And Soto Zen, which traditionally emphasizes shikan-taza, or “just sitting,”3 over the use of koan study, lacks the rigor and precision, the shouting and strong use of the keisaku or “warning stick” that characterizes the more spartan Rinzai tradition. (In Soto, the same word is pronounced kyosaku and is translated as “encouragement stick.”) Maezumi’s undramatic teisho, delivered in a murmur so soft that one could scarcely make out his words, was a gentle teaching very different from the vivid, often startling performances of the Rinzai masters.

Nevertheless, Maezumi emphasized strong koan study, which has rarely been associated with Soto Zen. Koan study seems to have evolved out of a split between Zen schools which occurred as early as the Golden Age of Zen in China, among the Dharma heirs of the Sixth Patriarch, Daikan Eno (Hui Neng, 638–713).4 One faction put special emphasis on Bodhidharma’s teaching of a “special transmission outside the scriptures . . . pointing directly to man’s own mind.” This was later identified with “sudden” illumination or enlightenment born of koan study—the profound contemplation, in zazen, of the cryptic acts, sayings, and responses of the old masters, such as the First Patriarch’s exchange with the Emperor Wu. A second faction, founded by Hui Neng’s foremost disciple, Seigen Gyoshi, is identified with “gradual” or “silent” illumination based on “just sitting,” citing the tradition that, after his encounter with Emperor Wu, the First Patriarch, Bodhidharma, crossed the Yangtze River, retired to Shorin Temple on Mount Su, and spent nine years “just sitting” in shikan-taza, “facing the wall.”

The sudden flourishing of the Zen schools is credited to Masters Sekito and Baso, “the two gates of elixir,” whose many disciples would travel all over China. Sekito Kisen, the remarkable “Monk on the Rock,” had studied with Daikan Eno in the Sixth Patriarch’s last years before receiving Dharma transmission from Seigen Gyoshi, and he tried in vain to heal the dissension between Daikan Eno’s forty disciples that would harden eventually into rival schools. Meanwhile Sekito composed the Sandokai, or “Identity of Relative and Absolute,” a seminal Zen document which laid the foundation for the Hokyo Zammai (Jeweled-Mirror Samadhi) teaching set down by his Dharma heirs. Sekito’s “gradual” lineages, distinguished by such eminent masters as Tozan, Sozan, and Tokusan, were eventually consolidated in the T’sao-t’ung school, called Soto (from Sozan and Tozan) in Japan.

Once Tozan asked Sozan, “Where are you going?”

Sozan said, “To an unchanging place.”

Tozan said, “If it’s unchanging, how could there be any going?”

Sozan said, “Going, too, is unchanging.”5Over the centuries the schism deepened as the “sudden” faction gained the ascendancy. A Baso lineage descending through Hyakujo (Po Chang) and Obaku (Huang Po) eventually produced Rinzai (Lin Chi), whose name is attached to what was to become the strongest school in the Land of T’ang. Another Baso lineage that included Nansen and Joshu would die out, as would the line that ended with Gutei. Soto lines were also disappearing for want of qualified Dharma successors. When Unmon’s line came to an end not long after his death in 949, the prestige and power of the Zen schools was already waning, and the Golden Age was at an end, yet the rivalry between T’sao-t’ung and Lin Chi continued fiercely.6

In the koan collections of both schools, there are wonderful “Dharma combats” between monks and masters, but the spare exchanges lack descriptive details, and only a few teachers such as Joshu and Unmon emerge from the records with distinct and idiosyncratic qualities. No teacher, not Daikan Eno (nor even Shakyamuni), comes to life so insistently as that hard-looking 110-year-old called Bodhidharma, who favored dispensing with abstractions, idle words in order to point directly at “the fact itself.”

Rinzai was washing his feet. Joshu came along and asked, “Why did Bodhidharma come from India to China? [What is this “Zen”? What is the essence of the Buddha Dharma?]

Rinzai continued washing his feet.

Joshu came closer, pretending he had not heard Rinzai’s response.

Master Rinzai poured away the dirty water.If koan are teaching devices designed to break down intellectual concepts of reality and open the way for a profound apprehension of the universal reality beneath, they are also pure expressions of enlightened mind. “The koan,” Maezumi-roshi says, “is quite literally a touch-stone of reality . . . in which a key issue of practice and realization is presented and examined by experience rather than by discursive or linear logic . . . to help us penetrate more deeply into the significance of life and death.” The student’s understanding is repeatedly fired in dokusan—face-to-face confrontation with a living buddha, as a Zen master of authentic lineage must be regarded—and tempered by the master’s teisho,7 which are not lectures but vivid manifestations of the Dharma.

The split between the “sudden” and “gradual” schools carried over to Japan, but from the start, in both China and Japan, the more interesting masters tended to ignore it. Maezumi-roshi’s teachers (both Rinzai and Soto) considered koan study important, and during sesshin he tested my understanding with the Sound of One Hand and its fourteen “checkpoints”—each one a separate koan—which are progressively more difficult. At one point he asked if I had ever had a kensho, and I related my premature experience of November 1971 and the few small “openings” or glimpses since that time. He murmured, “Just keep practicing and you will have another clear experience.” Of my “flat” sesshins he said, “They should not be flat—deep and quiet, yes. And when you get to this deep place, it is very comfortable, but you must not stay there—go beyond!”

Maezumi-roshi’s koan study mainly derives from a system transmitted by Hakuun Yasutani-roshi, who led sesshin in America almost every year between 1962 and 1969. His Los Angeles sesshin in 1967 was attended by a young aeronautics engineer named Bernard Glassman, born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1939. Glassman had been attracted to Zen writings in the late fifties, while still in college, but had no idea where he might find a teacher. About 1965, he heard about a weekly sitting, or zazen-kai, mostly for Caucasians, that was being held at the Soto temple in Los Angeles. After zazen there was tea and talk, and Glassman asked about the purpose of the slow walking between sittings. The head priest, Sumi-roshi, told a young Japanese monk to explain, and this monk said, “When you walk, just walk.”

“I guess that was my first Zen instruction,” says Bernie Glassman, better known today by his Dharma name, Tetsugen. “Not long afterwards, this monk left the Soto temple, and I did, too, because Sumi-roshi did not really speak English, and I was making no progress at all. Then, in 1966 or 1967, I heard that a Zen master was to give a talk at the Theosophical Society. The master was Yasutani-roshi and his translator was this same young monk, Maezumi-sensei, who had opened his own ‘Los Angeles Zendo’ on Serrano Avenue. I was very impressed by Maezumi’s translations, and I knew that he was someone I could study with.”

In 1968, young Bernie Glassman practiced zazen at the L. A. Zendo, and that year Yasutani came again and led a one-day sesshin. At dokusan, he gave Glassman the koan Mu. Afterward, Glassman had a lot of questions about Mu, but Maezumi-sensei, who had not completed koan study, would not answer them. Maezumi told his student to do shikan-taza until Yasutani came back the following year. By that time, all Glassman wished to talk about was shikan-taza.

“He had a dirty beard!” Maezumi recalls, remembering his first impression of young Glassman. “But he also had a flashing light in the eyes, and naiveté in the good sense of the word, open and ready to receive anything he could get. He became an exceptional Zen student because of his devotion to his practice, an ability to hurl himself into whatever he had to do. Very early, he knew how to throw the self away, to become selfless; that’s why he could do so well under hard circumstances. He knew what was important and what was unimportant, and he did not waste his time.” From the start, Maezumi-sensei gave this unusual student unusual responsibilities, and for fifteen months, beginning in September 1969, when Maezumi accompanied Yasutani back to Japan, Glassman was in charge at ZCLA.

In 1970, when Bernie Glassman received a Ph.D. in applied mathematics from UCLA, he was already employed as an aeronautical engineer and administrator for McDonnell-Douglas. He was also a fervent practitioner of Zen. In the year of his doctorate, he shaved his head and was ordained by Maezumi as a Zen monk or priest—neither term is accurate—in the tokudo, or “home-leaving,” ceremony, which almost persuaded his wife Helen to pack up their two infant children and leave home. Meanwhile he was contributing his salary to the new Zen Community of Los Angeles, which otherwise depended for support on the savings earned in a poor neighborhood by the gardening efforts of his new friend and teacher.

In December 1970, Maezumi completed his studies with Yasutani and received his Dharma seal. Yasutani-roshi never returned to the United States; he died in March, 1973, just prior to a planned journey to the United States for his ninetieth birthday. His friend Soen, concluding a long poem of commemoration, said:

Eighty-nine years, just-as-it-is!

How can I express, right now,

The grave importance of this very thing?In May 1970, Maezumi’s Rinzai teacher, Osaka Koryu-roshi, asked if he might come to America to complete Maezumi’s koan training and give sesshin in Los Angeles. “Because I was at the Zen Center all the time,” Tetsugen says, “I got to know both Yasutani-roshi and Koryu-roshi very well. Maezumi was close to finishing his own koan study and I had decided to put off my own, so that I could begin properly with my own teacher when he came back from Japan. But Koryu’s first teisho at that May sesshin was so powerful that I changed my mind. I went to work again on the koan Mu as soon as I sat down in the zendo that first day. I really got into it, and by the second day, both Koryu and Maezumi knew that, essentially, I was already there. I wasn’t asking any questions, I was just totally immersed. By the third evening, I had passed through it, but Koryu wanted something more from me, wanted me to go deeper, and when I went to dokusan on the fourth morning, I must have been right at the edge of something very powerful. I was still concentrating when I returned to the zendo, and right away I entered a different space, really beautiful, exquisite, very deep.

“All of a sudden, Maezumi-sensei shook me out of that space by really blasting me with MU! He had seen me come out of dokusan, and he knew that I was right on the point of explosion. So after I sat down, he stood right behind me, I don’t know how long he stood there, but when he saw that I was really settled in, he yelled MU! very loud, right there in the zendo! It broke the logjam; the world just fell apart! So Maezumi took me immediately to the dokusan room and Koryu-roshi confirmed the passing of Mu-ji, and Koryu and I spent about half an hour just hugging and crying—I was overwhelmed. At the next meal—I was head server—tears were pouring down my face as I served Koryu-roshi, and afterwards, when I went out of the zendo—well, there was a tree there, and looking at the tree, I didn’t feel I was the tree, it went deeper than that. I felt the wind on me, I felt the birds on me, all separation was completely gone.”

Relating this experience, Tetsugen looked slightly uncomfortable, and a bit awed, as if speaking of someone else. His kensho had been a classic one, not only because it came from a classic koan but because it occurred in the middle of sesshin, with two or three days left in which to deepen his insight. Koryu-roshi would later refer to it as one of the most powerful enlightenment experiences he ever witnessed.

“Maezumi-roshi had passed through Mu-ji in his first kensho, after three years of study with Koryu-roshi in Tokyo. He had his second major opening about a year later, while studying at Soji-ji, in Yokohama. I followed a very similar pattern. After that first kensho, I still had doubts about certain things, in particular reincarnation. When I asked Maezumi about it, he would not comment on my questions: he told me to reread the letters on the subject in The Three Pillars of Zen, then work on the question myself. And one day I was reading one of these letters in a car going to work—I was in a car pool, and my office was about an hour from the Zen Center—and a powerful opening occurred right in the car, much more powerful than the first. One phrase triggered it, and all my questions were resolved. I couldn’t stop laughing or crying, both at once, and the people in the car were very upset and concerned, they didn’t have any idea what was happening, and I kept telling them there was nothing to worry about!” Tetsugen laughed. “Luckily I was an executive and had my own office, but I just couldn’t stop laughing and crying, and finally I had to go home.

“That opening brought with it a tremendous feeling about the suffering in the world; it was a much more compassionate opening than the first. I saw the importance of spreading the Dharma, the necessity to develop a Dharma training in America that would help many people. Until then, I had believed in strong zazen, in ‘forcing’ people, using the kyosaku. That method encourages kensho, but the effects are not so deep and lasting, and anyway, it doesn’t work for everybody. I wanted to work with greater numbers because I saw the ‘crying out’ of all of us, even those who do not feel they are crying out. And that second opening had nothing to do with the zendo atmosphere, or working on a koan. The major opening can occur anywhere, we never know when it’s going to happen.”

In the early days of American Zen practice, much was made of kensho. Yasutani, for example, would announce who had had an “opening” at the end of each sesshin. Maezumi does not do this, and neither did Tetsugen when he began to teach. “Personally, I don’t stress openings, or talk about them, because I don’t want people to get caught up in that. Yet I think kensho is essential—it has to happen. And so long as the practice is constant and steady, so long as the student continues to practice without being intent on achieving some ‘special’ state, something that he or she has heard about, it will. When that idea of gain falls away, people open up. That’s why a teacher is so important—to keep the student from getting caught up in some incomplete idea of what it’s all about, and forcing his zazen in that direction.”

While in Japan, Maezumi had also resumed koan study with Koryu-roshi, who gave him Dharma transmission in 1972. “Like Yasutani, Koryu gave him inka right after he finished koan study, which is very unusual,” Tetsugen says. “For example, Harada-roshi waited three years before giving inka to Yasutani, who was already fifty-eight. Until 1972, Koryu had never given inka to anybody. In December of that year, he finally gave it to five people, all of whom except Maezumi had finished koan study at least five years earlier. Anyway, the speed with which Maezumi finished Koryu-roshi’s koan system was amazing. He started all over again from the beginning, and there are about four hundred koans, and he did the whole thing in three years, even though Koryu was only in the United States for three months each year! Before Koryu and Yasutani, his teacher had been his father. In a very unusual accomplishment, he received Dharma transmission from all three.”

In 1973, after Maezumi was formally approved by his own teachers as a roshi, Tetsugen was installed as his first shuso, or head monk, and three years later, with ZCLA well founded, Tetsugen left the aerospace industry for good. That summer he participated in the great opening sesshin at Dai Bosatsu, where our journeys crossed for the first time.

In early autumn of 1977, returning to ZCLA for a second sesshin, I applied for ordination as a monk. The impulse was vague (and no doubt tainted by spiritual ambition), but I had an idea that shaving my head would renew my practice. Maezumi-roshi, nodding politely, making his soft murmuring sounds, remained studiously noncommittal. Meanwhile, I continued intense study of the Sound of One Hand, not only with Maezumi but with Tetsugen-sensei, who had recently received shiho, or Dharma transmission, becoming the first Dharma successor in Maezumi-roshi’s apostolic line.8 I passed thirteen of the fourteen checkpoints but on the last, instead of a vital expression of the inexpressible, I could only come up with a weak intellectual “answer,” which was refused.

Roshi wished to give me the Dharma name Mukaku, which he said should accompany the name given me by Soen-roshi: Mukaku Isshin. This Mu is not the Mu of the koan Mu: it signifies “dream” in the sense of the illusory nature of the relative world, of everyday existence. Kaku is the awakening from that dream through realization. The final written and spoken word of Soen-roshi’s teacher, Yamamoto Gempo-roshi, was “dream,” Maezumi says. He presents me with his calligraphy of “Dream-awakening,” saying that Soen-roshi would approve this name.

At the end of sesshin, Tetsugen and I went over to Roshi’s house, where we celebrated with a good deal of sake. At one point Roshi, wonderfully drunk, put his arm around me with a beatific smile. “Mu-kaku! Do you see how greedy you are?” Disconcerted (since I know that I am greedy), I asked if he meant that I was pushing too hard in my practice, and he laughed, saying, “No, not hard enough!” Not understanding, I was bothered. Later, Tetsugen assured me it was simply a teaching, intended to “push all my buttons,” keep me off balance and alert. Roshi gave me a great hug when he said goodbye.

I had not made my peace with leaving Eido-roshi, and in September 1978 I telephoned Dai Bosatsu and was admitted for October sesshin. Arriving, I was sad to find how very few of the old faces were left, but Maurine F., accompanying me on a walk to Ho Ko’s grave, reported that Eido-roshi had recently said, “It is wonderful that some of you can lead strict moral lives. But for others, including me, this is very difficult.” Everyone interpreted these remarks as a strong sign that he was confronting his frailties at last. By this time, in apparent rejection of Soen-roshi, he had announced a formal separation of Dai Bosatsu from its parent monastery in Japan.

I found myself very glad to see him. I had missed him, and after three years, my righteous indignation had burned away. Having weathered his crisis, Eido-shi seemed very well, and his teisho were as lively as before. The new monastery, now completely furnished, still struck me as rather opulent, but otherwise the Dai Bosatsu atmosphere was exhilarating. Strong sesshin atmosphere was quickly induced by the strict, precise gongs, clappers, bells, the quiet click of the jihatsu bowls at table, the incense smell and smell of new tatamis, the fierce cleanliness, bare humble feet, dark mountain silence, which I remembered so well from other days.

In teisho, Eido-roshi recited a poem by Soen:

I went to the mountain seeking enlightenment

There was no enlightenment on the mountainside.

In desolation

I cried out and there came an echo.

I shouted again.

The echo came again.“What more Mu could we ask for than that echo?” Eido-shi demanded.

Late in sesshin, after six long days of pain, hurling myself to no avail against iron cliffs, I began to wonder why I had come, why I persisted year after year in this frustrating practice. A spider hanging from the zendo ceiling, spinning its Mu out of its belly, was my echo. I gave up struggling and settled calmly into moment-by-moment quiet Mu-spinning, breath after breath. Soon I was light and taut, at one with my pain in the same way that I was one with breathing, incense, far crows, and the autumn wind. Caw, caw was not different from Peter, Peter. Small silver breaths, farther and farther apart, scoured the last tatters of thought and emotion from the inside of my skull, now a silent bell. And very suddenly, on an inhaled breath, this earthbound body-mind, in a great hush, began to swell and fragment and dissolve in light, expanding outward into a fresh universe in the very process of creation.

At the bell ending the period, I fell back into my body. Yet those clear moments had been an experience that everything-was-right-here-now, contained in “me.” I mourned that bell that had come so swiftly, and tried to cheer myself during kinhin—“Who, me?” I murmured, right out loud, and began to laugh. The laughter quickly turned to weeping, and with the tears came a spontaneous rush of love for friends, family, and children, for all the beings striving in this room, for every one and every thing, without distinction. This feeling was followed instantly by a rush of doubt—had I really perceived something? All this damned soggy weeping—had my mind gone soft? Was I still too greedy for attainment?

At dokusan, describing what had happened, I burst into tears twice, as Eido-roshi beamed. As I did my bows, he struck me six times with the keisaku: “Very good! Good! Very good!”

On my evening walk I visited Ho Ko’s rock, and in her absence related to the rock just what had happened. “Out of my mind,” so to speak, I laughed and spoke aloud, as if the entire universe had come to attention. For want of any better plan, I burst out with a yell of joy, and yelled again, delighted by such freedom from my self.

And again the doubt came sweeping back. Perhaps I wanted such experiences too badly, perhaps I was exaggerating everything. I was filled with gratitude, and also I felt frustrated, aborted. Seven years had passed since that first opening of November 1971, which I now dismissed as premature and shallow, and this one, valid or otherwise, had scarcely started before being cut off by that bell, which—had it come even a few minutes later—might have rung those cliffs of iron down around my head.

I expressed my doubts and bitterness to Eido-shi, who made light of both, assuring me that more complete kensho experiences were still to come. By next morning I had mainly recovered, sitting calmly and strongly most of the day. In the evening, however, “forcing” again, sitting through kinhin with worn-out legs, I brought down on myself excruciating pain, and went reeling to bed with my teeth chattering, none the wiser for my joy, doubts, and ambitions. And it was now that I resolved, once and for all, to drop the practice of these sesshin notes, with their hoarding of miraculous states and “spiritual attainments,” with their contaminating clinging, their insidious fortification of the ego. I never kept a journal of sesshin again.

When I left next morning directly after breakfast, Maurine in her black cape stood smiling by the road. She has moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts, where she is president and teacher of the Cambridge Buddhist Association, and I have scarcely seen her since the weekend sesshin, just before Deborah’s death, when she came to see Ho Ko at the hospital. Yet in some way we know each other, we shall always be close. In parting, she said, “I love you,” with complete simplicity.

At the bridge, in rain, I stopped to peer into the black stream, thick as mercury with its tumbling yellow leaves. Here Beecher Lake began its long journey to rejoin the sea. I walked up to the boulder in the field to bid Ho Ko goodbye; I gathered tart apples from the ancient orchard by the gate. Then I drove to New England on a wild wet windy day, pursuing a wild wet windy sun that later opened out and softened a golden autumn afternoon. At his school, I had a good visit with Alex, his boy’s head so small in football shoulder pads too big for him, and later a warm evening with friends in northwestern Connecticut, with much wine and laughter and good conversation.

That evening I could not sit still. Leaving the dinner table rudely, I rushed out after supper, in a blue-black night with a wild moon spinning through the clouds. A little drunk, not knowing what was up, I strode down winding country roads by the light of the moon on the white birches, embracing the compliant trees, pressing my face to soft, thigh-smooth trunks, whispering and laughing with the silent company gathering around me, and otherwise playing the cosmic fool. Then I walked back to that white New England house, at peace, tears of happiness cool on my face in the black autumn wind down out of Canada. The feeling of being “blown out,” clear, would stay with me for another fortnight.

The following month, at sesshin in Los Angeles, I described my Dai Bosatsu sesshin to Maezumi-roshi. In regard to my aborted experience, he observed that it was not dai kensho, that is, great or “true” kensho, which wipes away the last traces of doubt. Later he said, “I did not say this was not kensho. You glimpsed the ox, but you did not see what color it was, whether male or female, fat or thin, poor or healthy. Work very hard on your koan, and then you will see the ox up close.”9

In koan study, I pass through the last checkpoint of One Hand, but Roshi, keeping me off balance, returns me to a previous point, although I protest that my presentation of it had been accepted the year before. I present it a different way and am refused. “What is the true state of one hand? In other words, what is the true state of your self? That will be good for you to work on until we meet again.”

All-inclusive study is just single-minded sitting, dropping off body and mind. At the moment of going there, you go there; at the moment of coming here, you come here. There is no gap. Just in this way, the entire body studies all-inclusively the great road’s entire body. . . . Gourd studies gourd all-inclusively. In this way a blade of grass is realized.

Pilgrimage

—EIHEI DOGENCHAPTER TEN

THE previous year, Maezumi-roshi had asked me to help Tetsugen-sensei establish a Zen community somewhere in the New York region. In June of 1979, Tetsugen held a sesshin at the Catholic retreat house in Litchfield, Connecticut, that I knew so well from Rinzai sesshins of other years.

Tetsugen-sensei calls his teisho “Dharma talks,” partly in deference to American Zen and partly because teisho are traditionally reserved for roshis. (In Japan, roshi signifies an elderly abbot of a training center, and is never used for a Zen master less than a half century old, but in America, where not a few “roshis” have never completed formal study nor received an authentic Dharma transmission in a recognized lineage, the term is used a lot more freely, often at the insistence of the students, for whom nothing less than a roshi will suffice.) Tetsugen speaks as easily as other people yawn, and his talks are a strong combination of beginners’ instruction and preliminary inspection of such classic koans as Joshu’s Mu (“Joshu’s way of expressing Buddha-nature, our true nature, the Absolute”) and “Where do you go from the top of a hundred-foot pole?” (“This is my favorite koan: Zen as a never-ending practice, Zen as our life”). He urges us to let go of all prior zazen experiences and expectations, including kenshos—they are just “stinks” to be aired out, since they taint the freshness of this present moment. At dokusan, he refuses my presentation of the last checkpoint of One Hand, even though Maezumi-roshi had accepted it. You understand more now, said he, and last year’s answer is no longer good enough.

In Rinzai study, in which one strives to present the “spirit” of the koan, there were many koans I had “passed” rather than passed through, as Soto teachers say, that is, thoroughly experienced and made a part of me. Knowing that my grasp was weak, I was almost as pleased as I was annoyed by Tetsugen’s rejection. Until now I had wondered how we would fare in a teacher–student relationship, since in Los Angeles this amiable fellow had mainly been my friend and fellow student. His rejection was appropriate, clearing the way for his own standards for koan study, and I admired that. To encourage me, he says that Harada-roshi, Yasutani’s teacher, had given seventy answers to this checkpoint before one was accepted, and that he, Tetsugen, had also been passed and then rejected on the same point. “Go deeper,” he said. “Come to dokusan as often as possible.”

I saw at once how much this man could teach me, and how exciting it would be to study with him in a formal, yet freewheeling way, unhampered by subtle language barriers and the strict and brittle protocol of Japanese Zen. Without effort we maintain an easy balance between friendship and strict deference, which I gladly award him on ceremonial occasions and in dokusan.

The insects are helping me again, a small white moth and also a wandering caterpillar on the carpet, lifting its weird head to inspect my presence: Who are you? A fly draws me taut with a buzz-z of warning, and I stop a mosquito with accumulated Mu power, closing my skin; off it goes with a loud whine of frustration. A bumblebee met with out of doors set me an example of precision, tending more than one blossom each second from flowers lilting in the wind.

My sitting is steady, uneventful. In six days of sesshin, I fail to pass through that final checkpoint, yet I am content. I’ve dropped some aggressiveness and haste, I am more patient, and content to do my best. Driving Sensei to his sister’s house on Long Island, I speak again about becoming a monk as soon as Roshi thinks me qualified. “Roshi just wants to be sure that you are serious. You’re qualified right now,” Tetsugen says.

I like and respect this round-eyed man of round-shouldered and compact construction whose easy smile and unlined forehead are held in balance by the intelligence that shines from beneath his fierce black brows. Like most American students, I have been attracted to the flavor of Asian Zen, so removed in its enigmatic self-containment from the wasteful sprawl of Western life, but I adjust more quickly than I had expected to the idea of a non-Japanese Zen teacher—Bernie Roshi! How different this man is, in style, manner, and appearance, from a quixotic “classical” Zen master such as Soen, a samurai-style master such as Eido, an elegant, autocratic scholar such as Maezumi, and no doubt other teachers from the East whom I do not know.

Those Asian teachers are here now, they have been here since the beginning, and in their teachings they will always be here; once American Zen is under way, it might be said, they will have truly arrived. But looked at from the relative point of view, no more will come; that first great wave of Japanese masters in America is also the last. Therefore it is crucial to develop our own teachers with training and standards at least as exacting as those of the best teachers in Japan.

Tetsugen-sensei is the first American Zen master to complete koan study as well as priestly training. He has been recognized as a Dharma-holder in formal ceremonies at the great Soto temples of Eihei-ji and Soji-ji in Japan. More important still, he is truly enlightened, having experienced two classical dai kensho. Despite his youthfulness—he was born in 1939—he is already a major influence on the future course of American Zen. He is also very ordinary, in the best Zen sense, without idiosyncratic airs or quirks that draw attention to him. He is—and also he is not—plain Bernie Glassman, with a passion for pizza, innovative ideas, and mechanical gadgetry of all descriptions.

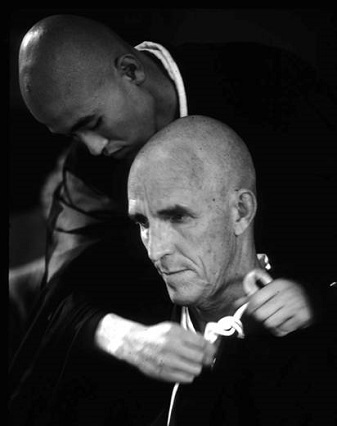

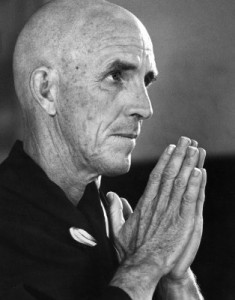

In 1980, in Riverdale-on-Hudson, Tetsugen founded the Zen Community of New York. He also officiated at my marriage in Sagaponack to Maria Eckhart. The following year, in a tokudo or “home-leaving” ceremony conducted by Maezumi-roshi, my head was shaved and I was ordained a Zen monk. (To Maria’s alarm, Maezumi stated that tokudo was a more important ceremony than marriage.) Maezumi gave me a new Dharma name, Muryo,1 and also his splendid calligraphy of Master Hyakujo’s “Sitting Alone on Daiyu Mountain.”2 The ceremony was attended by a few friends and by my older children, Luke and Sara, and also by old associates from my Rinzai days, two of whom, Lou Nordstrom and Lillian Friedman, had already joined ZCNY and would later receive tokudo from Tetsugen-sensei. Sheila offered this poem by the eleventh-century poet Narihara:

I have always known that at last I would take this road

But yesterday I did not know

It would be today.Tetsugen’s formal installation as abbot of ZCNY’s Zen temple, Zenshin-ji, had now been scheduled for June 1982. In the fall he would preside over his first three-month ango, or training period, to be led by his first shuso, or head monk. This training period would complete his studies as a Zen priest, after which his certification in this Soto lineage as a roshi or Zen master would become a formality.

Before his abbot installation, Tetsugen wished to make a pilgrimage to Japan in order to pay formal respects to those teachers, alive and dead, who are associated with his lineage and with his training. Since I am to be his first head monk, I shall travel with him as his jisha, or attendant. “After being shuso, you are a senior monk,” he says, “and your training enters a new phase. Your knowledge and understanding should be developing into prajna wisdom. Without prajna, you don’t realty know what you are talking about.” Tetsugen feels that, in America, there are too many self-described “Zen teachers” who really don’t know what they are talking about, and it is very plain that they embarrass him.

“After I became Roshi’s first shuso,” he says, “I considered myself very lucky to go with him to Japan, but I think it is better that you go beforehand, since being shuso will mean much more to you that way.” We would go to the historic Buddhist cities of Kamakura, Nara, and Kyoto; we would visit Maezumi’s last living teacher, Osaka Koryu-roshi, who had been one of Tetsugen’s teachers, too; and whether or not he chose to see us, we would pay our respects to Nakagawa Soen-roshi at the “Dragon-Swamp Temple,” under Mount Fuji.

The underlying purpose of our journey to Japan was a pilgrimage to those ancient places associated with Dogen Zenji, the thirteenth-century Soto Zen master who has emerged in recent years as one of the most exciting minds in the history of thought.

“One thing that first attracted me to Zen,” Tetsugen says, “was an essay by Dogen called ‘Being-Time,’ translated by Yasutani-roshi. I was studying quantum mechanics in those days, and it read like a twentieth-century treatise on relativity, on the interpenetration of space and time.”

The traces of the ebb and flow of time are so evident that we do not doubt them; yet, though we do not doubt them, we ought not to conclude that we understand them. . . . Man disposes himself and construes this disposition as the world. You must recognize that every thing, every being in this entire world is time. . . . One has to accept that in this world there are millions of objects and that each one is, respectively, the entire world—this is where the study of Buddhism commences. . . .

At one time I waded through the river and at one time crossed the mountain. You may think that that mountain and that river are things of the past, that I have left them behind. . . . However, the truth has another side. When I climbed the mountain and crossed the river, I was time. Time must needs be with me. I have always been; time cannot leave me. . . .

Because you imagine that time only passes, you do not learn the truth of being-time. In a word, every being in the entire world is a separate time in one continuum. And since being is time, I am my being-time. Time has the quality of passing, so to speak, from today to tomorrow, from today to yesterday, from yesterday to today, from today to today, from tomorrow to tomorrow.3

This passage is from Shobogenzo (Treasury of the True Dharma Eye), an extraordinary work of metaphysical exploration that few of Dogen’s contemporaries in the early Zen priesthood of Japan would have been able to appreciate even if they had had access to a copy. Within a century of Dogen’s death in 1253, Shobogenzo became an unread temple relic, and not until recent decades has it been perceived as a unique and shining vision that far transcends its original purpose as a synthesis of thirteenth-century Buddhist thought. Yet Dogen continues to receive more praise than real appraisal, and he remains all but unknown in the West, not because his language is opaque—it is brilliant, lucid, and poetic—but because he has attempted to convey a set of concepts—not concepts or even perceptions, but intuitions, apprehensions—for which no suitable vocabulary exists. To approach his formidable masterwork is to seek an ascent to a shining peak, glimpsed here and there against the blue through the wild tumult of delusion. With each step forward, the more certain one becomes that a sure path toward the summit can be found.

Maezumi-roshi is an inspired interpreter of Dogen’s thought. In his opinion, Dogen’s writings are “among the highest achievements not only of Japanese but even of world literature. His work . . . displays true poetic mastery. . . . Viewed philosophically, it is a near-perfect expression of truth. . . . Dogen Zenji’s expression is like an inexhaustible spring which gushes out of the ground naturally and without impediment. . . .”4 Maezumi-roshi has done a superb translation of Dogen’s Genjo-Koan (Actualization of the Koan), which one Western scholar has referred to as “surely one of the most brilliant, profound, and moving documents in world religious literature.”5

“What most impresses and attracts me about Dogen,” Tetsugen says, “is his ability and willingness to articulate his understanding of the universal nature of existence. He refuses to make any distinction between the absolute and relative realities. Many teachers will say that ‘you cannot express the inexpressible,’ and they do not try. But teachers like Yasutani and Maezumi don’t agree, and I feel as they do: if you perceive deeply enough, a clear and simple way to express it can be found. Dogen tried to set down in words a very profound understanding, and I think he succeeded. His actions, his practice, and his words—he puts it all together.”

Dogen is many centuries in advance of his pre-medieval epoch, and his vibrant efforts to transcend the old limits of language, like his insistence on the identity of space and time, would not be appreciated until seven centuries later. Like all born writers, he wrote for the sheer exhilaration of the writing, in a manner unmistakably fresh and poetic, reckless and profound. Though the risks he takes make the prose difficult, one is struck at once by an intense love of language, a mastery of paradox and repetition, meticulous nuance and startling image, swept along by a strong lyric sensibility in a mighty effort to express the inexpressible, the universal or absolute, that is manifest in the simplest objects and events of everyday life.

When we view the four directions from a boat on the ocean

where no land is in sight, it looks circular and nothing else.

However, this ocean is neither round nor square,

and its qualities are infinite in variety. It is like a palace;

it is like a jewel. . . .

When a fish swims in the ocean, there is no limit to the water,

no matter how far it swims.

When a bird flies in the sky, there is no limit to the air,

no matter how far it flies.

However, no fish or bird has ever left its element

since the beginning. . . .6

You should entreat trees and rocks to preach the Dharma, and you should ask rice fields and gardens for the truth. Ask pillars for the Dharma and learn from hedges and walls. Long ago the great god Indra honored a wild fox as his own master and sought the Dharma from him, calling him “Great Bodhisattva.”

Bowing, Prostrating the Marrow

—EIHEI DOGENCHAPTER ELEVEN

THE ancient town of Kamakura on the Pacific sea coast of Japan is celebrated for its huge bronze Buddha, which rises forty-one feet from the gardens of Kotoku-in Temple against a background of steep, forested hills and island sky. According to a postcard sold on these flowered premises, this primordial “Buddha of Boundless Light,” was cast in A.D. 1252 “at the request of Miss Idano-no-Tsubone and Priest Joko.” The hall which enclosed it was borne away by a tidal wave of 1495—and doubtless the dust of Miss Idano danced in the great dun flood—but the Daibutsu or Great Buddha sat unperturbed, turning green in long, calm centuries in the open weather. On this April Sunday, in cherry-blossom festival, the travel-mad Japanese have hurried in orderly thousands to the town, and flocks of pretty schoolchildren in navy-blue uniforms and bright yellow caps dart and flutter through the gardens. Cheeping, they peer around the door in the Buddha’s platform, and an emanation of sweet voices pours from the vast emptiness within.

On wayside shrines, stone Jizo Bodhisattvas, protectors of wayfarers and children, are decked out in red caps and smocks and honored by tossed blossoms. Bright fresh flowers, fruit, and flags bring the avenues to life, and even the Pacific fish in the open markets—mackerel, silver mullet, sole, squid, salmon, red-fish, and bonita—are starry-eyed and sparkling if not entirely cheerful in appearance. Pink-white paper lanterns in the pink-white-blossomed trees sway in the breeze, and altars of gold are carried on stout poles by teams of youths in archaic dress who shout and jump as they lurch their burden up the street, for today there is a celebration at Hachiman-gu, the huge shrine of the old Shinto god of war on the north side of the city. From the sidewalks the celebrants are cheered by young friends in American-style jeans and sweatshirts emblazoned with American-style legends: Fascination Ski, Shooting 4 Fomation, Apricot Sports, Rude Boys, Peppermint Gal.

At Hachiman-gu, the red-bridged canal is speckled with fallen blossoms, and flocks of white pigeons snap wings on the blue sky as they wheel over the crowds. An officiant in a high black, shiny Shinto hat strikes the big drum, the pigeons fall. Long horns resound, the red flags flutter, and a florid householder who presides over the family picnic lifts his bottle of rice wine to the big gaijin (“outsiders” or foreigners) and shouts in celebration. As in many country Japanese, his face is open and his eyes round in unfeigned innocence and acceptance of his life. Surely this ruddy and befuddled face was here at the dedication of Hachiman-gu in 1063, when the shogun Yoshiye, at the ocean gate, set free a multitude of Japanese cranes with silver and gold prayer strips attached to their legs, and lent an intoxicated shout to the wind of awe that rose at the spectacle of the great white birds, trailing the streamers down the Pacific sky.

Among Kamakura’s many temples, the most celebrated is Engaku-ji, a “mountain” or head monastery of Rinzai Zen built into the evergreens in a ravine on a high hill north of the town. “Even when he reached Kamakura and the Engaku-ji Temple, Kikuji did not know whether or not he would go to the tea ceremony”—so begins One Thousand Cranes, a novel by the 1958 Nobel Prize winner Yasunari Kawabata. The immense peaked entrance gate stands at the mouth of the ravine in a company of guardian pines and cedars, and behind this portal, tiled rooves with their dull pewter shine climb between heavy forest walls, straight to the throat of the ravine. In spring, the weather-darkened walls are half hidden in cherry blossom clouds and pale bamboo; delicate light-filled red-bronze leaves of a Japanese maple flutter and point at the might and weight of the old buildings. Here at Engaku, one moonlit night, the nun Chiyono, hauling water, attained enlightenment when her wood bucket collapsed and the water splashed onto the ground. In gratitude, she wrote a poem:

In this way and that I tried to save the old pail

Since the bamboo strip was weakening, about to break

Until at last the bottom fell out.

No more water in the pail!

No more moon in the water!1We ascend the steep hill by leafy walks that pass beneath the bursts of sun-filled blossoms. Two monks in black work tunics, pates tight-bound in white cloths, pad past, incurious; they are hauling firewood slung from a pole. When Tetsugen, who speaks some Japanese, asks to be shown the former dwelling of Soyen Shaku, first Zen teacher in America, another monk points doubtfully at a cloistered cottage. He seems not to have heard this name before.

Bronze pigeons cross the trees where the ravine vanishes into the forest. In a pond beneath a moss-green wall, the sun glints on the raised red-and-yellow head of an old turtle on an ancient rock, drawing its slow eyelid closed as it stares and listens, winking out the world, then letting the world in slowly, slowly once again.

In June of 1973, on the way to sesshin at Ryutaku-ji, Soen-roshi’s students descended from the coast train here at Kamakura to visit Engaku-ji, the immense Daibutsu, and the house and library of D. T. Suzuki, now a museum. We also chanted and sat in zazen at the San-un zendo established here by Yasutani-roshi and administered by his disciple, Koun Yamada-roshi.2 Many years ago, at high school and at Imperial University in Tokyo, Yamada’s roommate and close friend had been Soen Nakagawa, a student of Japanese literature whose hero was the Zen hermit-poet Basho. Much influenced by Basho’s style of life, this young poet was ordained a Zen monk3 not long after his graduation in 1930. Inspired by Soen, Koun Yamada took up Zen studies under Yasutani-roshi fifteen years later, and his profound enlightenment experience in 1953, following a stay at Ryutaku-ji, is described in a wonderful letter to his old friend (addressed here formally as “Nakagawa-roshi”):

The day after I called on you . . . riding home on the train with my wife . . . I ran across this line: “I came to realize clearly that Mind is no other than mountains and rivers and the great wide earth, the sun and the moon and the stars.” I had read this before, but this time it impressed itself upon me so vividly that I was startled. I said to myself, “After seven or eight years of zazen I have finally perceived the essence of this statement,” and couldn’t suppress the tears that began to well up. . . .

Meanwhile the train had arrived at Kamakura station and my wife and I got off. On the way home I said to her, “In my present exhilarated state of mind I could rise to the greatest heights.” Laughingly she replied, “Then where would I be?” All the while I kept repeating the quotation to myself. . . .

At midnight I abruptly awakened. At first my mind was foggy, then suddenly that quotation flashed into my consciousness, and I repeated it. Then all at once I was struck as though by lightning, and the next instant heaven and earth crumbled and disappeared. Instantaneously, like surging waves, a tremendous delight welled up in me, a veritable hurricane of delight, as I laughed loudly and wildly, “There’s no reasoning here, no reasoning at all! Ha! Ha! Ha!” The empty sky split in two, then opened its enormous mouth and began to laugh uproariously: “Ha! Ha! Ha!”

I was now lying on my back. Suddenly I sat up and . . . beat the floor with my feet, as if trying to smash it, all the while laughing riotously. My wife and youngest son, sleeping near me, were now awake and frightened. Covering my mouth with her hand, my wife exclaimed, “What’s the matter with you? What’s the matter with you?” But I wasn’t aware of this until told about it afterwards. My son told me later he thought I had gone mad. “I’ve come to enlightenment! Shakyamuni and the Patriarchs haven’t deceived me! They haven’t deceived me!” I remember crying out. When I calmed down I apologized to the rest of the family. . . .

That morning I went to see Yasutani-roshi and tried to describe to him my experience of the sudden disintegration of heaven and earth. “I am overjoyed, I am overjoyed!” I kept repeating. . . . Tears came which I couldn’t stop. I tried to relate to him the experience of that night, but my mouth trembled and words wouln’t form themselves. In the end I just put my face in his lap. Patting me on the back, he said, “Well, well, it is rare indeed to experience to such a wonderful degree. It is termed ‘Attainment of the emptiness of Mind.’ You are to be congratulated!” . . .

Although twenty-four hours have elapsed, I still feel the aftermath of that earthquake. My entire body is still shaking. I spent all of today laughing and weeping by myself. I am writing to report my experience in the hope that it will be of value to your monks and because Yasutani-roshi urged me to. . . . That American [Philip Kapleau] was asking us whether it is possible for him to attain enlightenment in one week of sesshin. Tell him this for me: don’t say days, weeks, years, or even lifetimes. Tell him to vow to attain enlightenment though it take the infinite, the boundless, the incalculable future.4

Yamada-roshi had been absent on the day of our visit in 1973 (he administers a small Tokyo hospital where his wife is head surgeon), but on this April Sunday, nine years later, a zazen kai—a day of sitting meditation—was just coming to an end when Tetsugen and I arrived in the late afternoon.

Although Yamada was ordained a monk and became Yasutani’s first Dharma successor, he had no training as a priest and no longer shaves his head. At seventy-five, he is a big man of strong presence, with silvering dark hair, dark pouches like shadows beneath watchful eyes, and an expression of wry humor tinged with regret. In the past century (as Soyen Shaku had anticipated), a number of Zen monasteries had closed down or sold off their lands for lack of interest among modern Japanese. “It is no exaggeration to say that Zen is on the verge of completely dying out here in Japan,” Yamada has written. “Some people may think I am stretching the point, but sad to say, this is the actual state of affairs.”5 Yasutani had also been of this opinion, and both teachers blamed it on the decline of zazen practice and of hard training directed toward “Attainment of the Emptiness of Mind.”

At tea in his house after the zazen kai, Yamada-roshi was joined by three old friends6 who had also received Dharma transmission from Yasutani. A little earlier, introducing the American visitors to Yamada’s students, one of these teachers had mentioned that Tetsugen-sensei had attained “a complete enlightenment,” and Yamada had nodded in confirmation, saying, “I have met him in dokusan and it is so.”

Tetsugen had been bothered by that word “complete.” “I don’t think it is ever complete,” he told me later. “That’s why my favorite koan is, ‘Where do you step from the top of a hundred-foot pole?’ Zen is your life—it is life itself!—and you must always go further and deeper.”

Since returning from America in 1975, Soen-roshi had become a hermit, Yamada told us; these days he saw nobody at all. Learning that I had once been Soen’s student, he fetched a published volume of his old friend’s haiku. “There is also a much fatter one,” he said. Of Soen Nakagawa the American poet Gary Snyder has remarked that “In Japan he had a tremendous stature as a haiku poet; he is considered the Basho of the Twentieth Century.”7 Yamada-roshi confirms this opinion. “Soen-roshi is one of the great haiku poets, one of the very best in Japan. But he does not write haiku anymore. He is in pain from an old head injury, and from other reasons”—here he paused and cocked his head, peering out from beneath dark, heavy lids. He wished to see if I was aware of Soen’s rupture with Eido-roshi, and perceiving that I was, said, “A great tragedy. Also, he is suspicious of Western medicines, so he deals with the pain by taking too much sake.” Yamada-roshi shrugged. We could visit Ryutaku-ji if we liked, but there was no hope that Soen-roshi would see us.

In June 1973, Soen-roshi’s students had traveled from Kamakura to Mishima, under Mount Fuji, arriving at Ryutaku temple, in the foothills, in time for a late supper with our teacher. Next day, the roshi awoke us at 3:30 A.M. for morning service, after which we visited the graves of Hakuin Zenji, founder of this temple, and Torei Zenji, who had seen to its construction. On the moss-covered hillsides we paused to admire bright green frogs and huge multicolored carp in the temple’s goldfish pond, and the rice paddies and pines on the slopes below. Pointing at swallows, the roshi instructed us on tatha, or “suchness,” the awareness of everything just as it is: “The swallows come back to Ryutaku by just-coming, no thought of migration, navigation—they are just-coming!”

Ryutaku’s new abbot, Sochu-roshi (who would attend the opening of Dai Bosatsu three years later), had made us welcome in a greeting ceremony, after which a ceremony was held for the opening of “International Ryutaku Zendo.” With these priestly formalities at an end, Soen-roshi had immediately brightened, whisking up thick green koicha tea, then serving sake and lemon wine in his snug quarters at the top of the long stair up the steep hillside. Uproarious, we blew bamboo whistles and triton horns. Then a red demon mask appeard from behind a sliding screen; the mask looked us over one by one, and the laughter died. When Soen dropped the mask, his face was serious. “I have taken off my mask,” he said. “Now take off yours.”

Soen-roshi led us down the stairwell to the entrance, where he sent us off with his kind monk Ho-san to Nara and Kyoto; we were to return here for sesshin the following week. Standing beneath a tattered old umbrella, in spring rain, he spoke of the great “weightless Buddha” at Nara. “See everything with hara,” he said, slapping his stomach two inches below the navel, “not just with eyes.”

When we look at human life, we see that often the compassionate person suffers and dies, while the wicked person who gets along in the world by means of violence is happy and lives a long life. Also, the decent person is unhappy and wretched, while the wicked person who commits offenses without ever thinking twice about it is happy. This is the way it seems, and we may wonder why it is this way. When we study the situation, we see that the person who trains in a superficial way thinks that cause and effect have nothing to do with this life and that misery and unhappiness have nothing to do with cause and effect. This person does not understand that the law of cause and effect never deviates, any more than a shadow or echo deviates from its source.

Deep Faith in Cause and Effect

—EIHEI DOGENCHAPTER TWELVE

NOW a decade has passed, and once again I travel southeast toward Nara and Kyoto. Today I am a Soto monk, not yet white-haired nor sparse of tooth but older and more scarred than my fresh-faced teacher. Isshin-Mugaku-Muryo stares out the window. I have never cared much for Dharma names, which strike me as “extra” in the context of American Zen, and which reproach me for my stubborn flaws of character. Yet they serve as a reminder (I suppose) not to cling to the badge of identity in my given name—the illusion of separation, which is ego—but to aspire as best I can to One Mind, Dream Awakening, Without Boundaries. Sometimes in zazen on my black cushion I approach these states, but in the much more difficult zazen of daily life, there remains a dismaying separation between what I know and what I am.

Near Ise, the train turns inland toward Mount Yoshino, a shrine of poets for more than a thousand years. (“I could no longer suppress the desire to leave for Yoshino,” wrote Basho, “for in my mind the cherry blossoms were already in full bloom.”)1 The mountains rise under the sun to westward. The iron track threads dark, steep valleys gouged by swift gray torrents; bursts of lavender azalea blossoms near the higher forest of tall pines are the only light. Some of the perched villages are modern, flat, of raw chemical colors, while others are somber assemblies of high-peaked old dwellings with pale shoji windows and pewter-colored rooves, the tiles long weathered to dark mountain hues.

Emerging onto a broad valley floor, the train approaches the ancient capital at Nara from the south and east. I point out to Tetsugen-sensei a wild duck, setting its wings in swift descent through the spring twilight toward the cold gleam of a sedentary river. Wild things are sparse on this central island of Japan, and the duck stirs me.

Tetsugen is less interested in wild ducks and ancient landscapes than amused by my reactions to them. Art and literature (and landscape) don’t attract him much, though he delights in opera. His leanings toward engineering and mathematics are still strong, he loves computers, and anyway he is an unabashed fanatic who thinks mostly about how best to transmit the Buddha Dharma to American students, a task for which he is admirably suited even in appearance. With his big head, round-shouldered slouch, and prominent, piercing eyes, Tetsugen reminds Japanese teachers of Zen’s first great spiritual messenger, Bodhidharma, who carried the Dharma from India to China.

In the distance, as Nara draws near, rise the jutting roofs of the great outlying temples that came into existence thirteen centuries ago, with the arrival of the Mahayana teachings in the backward islands known to the Chinese as “the Land of Wa.” Half hidden in an isolated grove west of the city stands a huge compound of white-walled dark brown wooden buildings with high gray-tiled rooves. Horyu-ji is the first seat of Japanese Buddhism, established in 607 as a seminary or “learning temple” of the Hossu sect. Farther east, at Yakushi-ji (where we spent the night in 1973), in a wonderful airy open court of golden and red buildings, stands the famous East Pagoda, last surviving example of the mighty architecture of this period.2 This early Buddhism in Japan was not yet “Zen,” although Zen traces may have been apparent: Japanese visitors to China, staying close to the cities and old monastic centers, had little exposure to the new “Zen” school which was developing in China’s southern mountains.

By the middle of the sixth century, the first sutra books and Buddhist relics had turned up in Japan. Unlike India, where the teachings of Shakyamuni had to compete with Hinduism and Vedanta—and unlike China with its Taoism and Confucian law—Japan had no philosophical religion or literate priesthood, no body of teachings, nor a written language. The early peoples who had arrived over long ages from the mainland coasts lived in shifting settlements along the rivers and practiced an indigenous form of sun and nature worship (later called Shinto, “the Way of the Gods”). Therefore these first holy objects, accompanied by a written language, made a great stir in the rude assemblies that history books refer to as the imperial courts, and were used to political advantage by the enterprising Soga family, which soon came to dominate the more traditional clans. In 593, Umako no Soga took the precaution of murdering the emperor to ensure the accession of a crown prince who would proclaim Buddhism as the state religion.

Despite the bloody circumstances of his ascendancy, Shotoku Taishi, the “father of Buddhism” in Japan (d. 622), was a sincere practitioner who propagated the moral and philosophical precepts of the new religion and issued a list of behavioral edicts in an effort to bring unity and harmony to his backward country. Soon there were more than forty Buddhist temples in this region, complete with relics, priestly vestments, and colorful ceremonies to attract the people. Most of these ceremonies, as in Shinto, were devoted to curing, summoning rain for crops, and other practical considerations.3

Enthusiasm in imperial court circles for the new culture from “the Land of T’ang” was evident in the foolhardy adoption of the complicated Chinese ideographs for the relatively simple Japanese language, and a somewhat less disastrous decision to replicate a Chinese city in Japan. Until now there had been no capital town in the islands; the imperial court had moved with each new reign, not only to invite good fortune and evade epidemics but because it was easier to replace than to rebuild the frail wood buildings. With the advent of a more sophisticated culture, this makeshift situation was no longer tolerable, and in 646 a reform edict authorized the construction of a capital city on the model of the Chinese capital at Ch’ang-an. The new “Central City” of Nara, some forty miles inland from the present Osaka, was eventually laid out in A.D. 710, and remains a Buddhist shrine twelve centuries later.

In this period, the emperor Shomu, inspired by reports of an eighty-five-foot “Universal Buddha” installed by T’ang dynasty rulers at Lo-yang, proposed to erect a local version here at Nara. In traditional circles, his grandiose plan was widely denounced as a threat and insult to Shinto deities, and the Buddhists perceived that the Way of the Gods, still strong in the outlying districts, would have to be placated. In 742 the energetic monk Gyogi, a leader of the Hossu sect, carried a holy relic to the Sun Goddess at the great Shinto shrine at Ise, inquiring respectfully as to her views on the proposed Buddha, who was, he explained, her spiritual descendant as well as her own emissary on earth. In a loud voice, the oracle proclaimed in Chinese verse that news of this enterprise was very welcome to her. Not long thereafter, the Sun Goddess, appearing as a disc in the emperor’s dreams, revealed to him that the Sun was none other than this supreme Buddha. And since Buddhism has ever made room for the indigenous faiths it has displaced, adopting their deities as Dharma guardians and even Buddha manifestations, the Shinto war god Hachiman confided in the oracle that he wished to serve as a protector of the Dharma, and was speedily pressed into service by the Hossu sect at Yakushi-ji, where he appears in the plain garb of a Buddhist priest.4

And so the emperor commissioned the Dai Butsu or Great Buddha at Nara, which rises fifty-three feet from the bronze lotus of its throne. Though less than two-thirds the height of the Lo-yang figure and entirely innocent of artistic distinction, it was the greatest technical accomplishment ever beheld in the Land of Wa. The great hall that replaced the original Daibutsu Hall after a twelfth-century fire is 284 feet long, 166 feet wide, and 152 feet high—by far the largest wooden building in the world—and the statue itself is a conglomerate of 500 tons of copper, tin, and lead, heaped up in sections, supporting a twelve-foot head cast in a single mold—“the weightless Buddha at Nara,” Soen-roshi had called it in 1973, sending his students off to have a look at it.

Todai-ji, which grew up around the black Daibutsu, is located at the base of the eastern mountains that surround this flat, rich valley. The huge red Buddha Hall is fronted by an enclosed court perhaps one hundred yards long by one hundred wide, the whole surrounded by a deer park of old pines. More people, perhaps, than existed in all the Land of Wa when Buddhism arrived in the sixth century were visiting the Dai Butsu on the fine spring day of our own visit. However, we are the only visitors at Monk Gyogi’s small, forgotten temple5 awaiting fire and decay in a little park of flowering trees and untended graves among the hard-edged structures of the modem city. Reputedly it was inside these brown, worn, shuttered buildings that zazen was first practiced in Japan.

Kohuku-ji, a mile away across the deer park, is noted for the five-story golden pagoda paid for originally by the powerful Fujiwara clan; other eighth-century Buddhist temples were also dependent on their wealthy patrons. Awarded large tracts of tax-free land by the imperial court, and generously endowed by gifts from aspirant Buddhists, the rich monasteries became centers of learning and culture, sharing their prosperity to a certain degree through the creation of charitable institutions. But as in China, the priesthood’s dependence on aristocratic influence soon led to corruption and decline. Few of the new Buddhists understood the profound nonmaterial nature of the teaching, and no true teachers seem to have developed, even though the great classical period Ch’an Buddhism in China was well under way.

In the Nara period, Kegon (Hua Yen) Buddhism also became established in Japan, but throughout the T’ang dynasty, when Chinese Zen was at its height, Japanese Buddhism remained primitive. By 779, hordes of parasitic monks and nuns from new temples in the remote districts had gathered to the feast at Nara, where the power of the priests in court had encouraged political ambitions as well as excess and dissolution of every kind. Possibly this rampant corruption encouraged the decision, three years later, to remove the court to Nagaoka, a few miles to the northward, despite the great inconvenience and expense, but it seems more likely that the hasty departure reflected obscure maneuvers of the Fujiwara clan, in particular Tanetsugu, a favorite of the emperor Kwammu, who was allowed “to decide all matters, within and without.” In 785, Tanetsugu was assassinated by the emperor’s brother, Prince Saware, who paid for this deed with his own life, and these dark events discouraged the completion of Tanetsugu’s plans for the new capital, which was moved again in 793 to a plain perhaps twenty miles to the northeast, called Heian-kyo.

The new capital, later called Kyoto, was to become one of the largest cities in the world, with a population that may well have approached a half-million people, but as at Nara, there was little about it that could be called Japanese. Every aspect of its culture, from its architecture to its etiquette, was a pains-taking imitation of T’ang dynasty culture in China. For the next two centuries, the Heian aristocracy preoccupied itself with art and poetry in the Chinese style, infused by mujo, a rarefied, romantic sense of life’s impermanence, often symbolized in the fall of cherry blossoms in spring.6

The founding of Kyoto coincided with ominous invasions of the main island of Honshu by a wild blue-eyed people called Emishi (the “Hairy Ainu”) from the northern island of Hokkaido, who “gathered together like ants but dispersed like birds,” and in 794, the first shogun or “General for Subduing the Barbarians” was appointed. Meanwhile, the Buddhist monasteries were controlled by the imperial court and the Fujiwara clan, which endowed the tax-free lands and built the temples. After 877, when a Fujiwara was named the first minister or regent, the power of the emperor himself was usurped by this aggressive family; its daughters were married regularly to the emperors and princes, and none but Fujiwara consorts reached the throne. Lacking true teachers, the corrupt monasteries, seeking special privilege and tax-free lands, competed for the favors of the aristocracy (which held almost all the important monastery posts). At the same time, the priests resorted to occult ceremonies and tantric practices of the Shingon sect to win the interest and allegiance of a populace which understood almost nothing at all about the true nature of the Buddhist teachings.

In 788, an inspired eighteen-year-old monk named Saicho, after ordination at Todai-ji, withdrew from Nara to the high forests on Mount Hiei west of Kyoto to escape the rigid structures and corruption of the priesthood and to renew Shakyamuni’s emphasis on meditation. In 804 he spent a year in China at the monastery at Mount T’ien-tai, adding Zen precepts and esoteric teachings to the Tendai (T’ien-tai) teachings he brought back to the Land of Wa. Saicho established a twelve-year course in religious studies that would make Mount Hiei the greatest school of religion in the nation, and it was in his Tendai temple, known today as Enryaku-ji, that most of the later schools of Buddhism would have their start.

But Japanese Buddhism remained a pale, priest-ridden imitation of the Chinese schools, since the great teaching lineages that ensured the continuity of the true Dharma had not yet made their way across the China Sea. By the tenth century, in open contravention of the Buddhist precepts, Enryaku-ji (and the large Nara temples) maintained standing armies, since the strength of their temples depended, not on the power of the Buddha Dharma, but on the armed monks who battled in Kyoto’s streets with monks of other monasteries. In one such battle, early in the eleventh century, about 40,000 monks, backed by mercenaries, are thought to have taken part.

The pollution of the Buddha Dharma, already under way by the end of the Nara Period, would culminate about 1050 in what the faithful themselves called the Age of Degenerate Law, a dark epoch of epidemic, earthquake, fire, famine, banditry, and murder. The Fujiwara, to whom the imperial government had long since ceded its prestige, had been infected by their own decadence even as they attained the summit of their power. Their armed monks were now a threat to their own masters, and the soldiery of feudal lords in the outlying provinces was finally called upon to bring the anarchy under control. These lords—descendants of outcast emperors—detested the decadent despotism at Kyoto. Over the course of the next century, the Fujiwara were challenged and defeated by the strong provincial clans, notably the Taira or Heike, descendants of that Emperor Kwammu who had done so much to bring the Fujiwara into power.7 The Heike were challenged in their turn by other claimants, notably an alliance of strong clans that was grouped around the family Minamoto. In five bloody years between 1156 and 1160, when the Fujiwara were already in retreat, the Heike gained a brief ascendancy over the Minamoto and established their own emperors in court, but within a few years, they were overthrown by Yoritomo Minamoto in a series of epic battles that culminated in 1185 in the great sea coast battle at Dannoura. Within four years Yoritomo had eliminated the last resistance of the Fujiwara in the eastern provinces.

As shogun, or administrator general, Yoritomo established his own headquarters at Kamakura, three hundred miles east of Kyoto. A feeble court persisted in that city, but the Heian period was at an end. For the next seven hundred years Japan would be governed by military shoguns, mostly of Minamoto origin, who paid mere ceremonial homage to the emperors.

Toward the end of the twelfth century, on a second pilgrimage to China, a Tendai priest called Eisai received Dharma transmission in the Oryu branch of Rinzai Zen. In The Propagation of Zen for the Protection of the Country, Eisai deplored what had become of the old Buddhism on Mount Hiei. His proposed reforms won the approval of the second Minamoto shogun, who sponsored the construction of Kennin Temple, in Kyoto.

Kennin-ji deferred to the older sects by including Tendai and Shingon subtemples, but Master Eisai, nonetheless, might be called the first Zen teacher in Japan. Not until a century later would Master Daio institute the first Rinzai teaching that did not have to take the older sects into account. Daio’s “poem” “On Zen” is still recited by Rinzai students in America: