ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

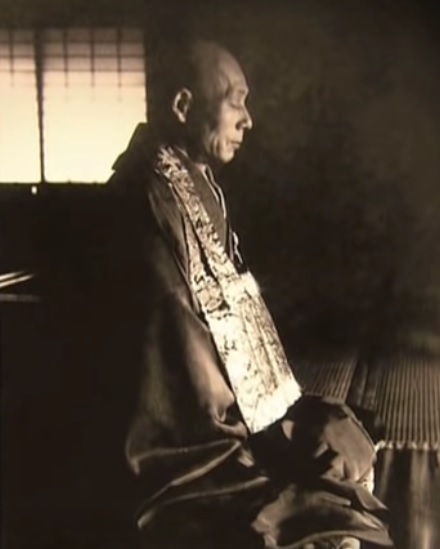

宮崎 (栴崖) 奕保 Miyazaki (Sengai) Ekiho (1901-2008)

78th abbot of Eiheiji, at 95 years old

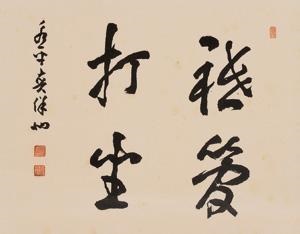

「祇管打坐」 Shikan-taza

Calligraphy by Miyazaki Ekiho

How to Live Here and Now

by Rev. Sensho Watanabe

Sotoshu Specially Dispatched Teacher

Toryuji, Niigata, JapanBerkeley Zen Center • Shogakuji

California, U.S.A. September 20th, 2019.I practiced at Daihonzan Eiheiji from 1981–1984.

This was at the time that Miyazaki Ekiho Roshi,

later to become the 78th Head Abbot of

Eiheiji and who died in 2008 at the age

of 108, who was Director of Eiheiji. He

served in that position as the person with the

most responsibility for looking after the monastery.

It happened that at that time I was assigned

for seven months to be part of the crew who

served as the Director Roshi’s assistants. There

were six of us monks, each of us was in our

second year of training at Eiheiji. Every day, our

work assignment changed.

The assignment that needed the most study

on our parts was that once every six days one of

us had to be his personal attendant (Anjya),

helping Miyazaki Roshi. At Eiheiji, the monks

rise at 3:30 a.m. However, Roshi would come out

of his room between 2:50 and 3:00 a.m. On the

day I was his attendant, I was expected to follow

him like a shadow from the time he left his

room. So, we would get up at 2:30 a.m. and after

using the toilet and washing up, we would wait

outside his door, kneeling. Then, huffing and

puffing with deep breaths, Roshi would come

out of his room. Since this was before the wakeup

bell at 3:30 a.m., the hallways were dark

because the lights were not yet turned on. While

shining a flashlight so he could see where he

was going, we would climb 100 steps and

proceed to the Zendo. No matter how big Eiheiji

is said to be, if you walk for ten minutes you can

reach the Zendo.

In the inner room of the Zendo, the monks

were still sleeping. While lights out is said to be

at 9:00 p.m., and this is rest time, in actual fact,

it often happened that it was after 10:00 p.m.

before the monks went to bed. This was because

we needed time to reflect on the day just

finished as well as to prepare for the next day.

Since the wake-up bell is at 3:30 a.m., the

monks were fast asleep when Roshi and I

reached the Zendo. Without paying any attention

to the sleeping monks, Roshi would remove

his slippers and get up on a half-size tatami mat

in the outer hall near the entrance to the Zendo

and sit in zazen. I would arrange his slippers

and sit at one end of the outer hall.

This was at about 3:10 a.m., which meant

that we sat there in zazen for 80 minutes or twice

as long as the others. By the time the bell to end

zazen was hit, my legs had gone beyond numbness

to the point where I couldn’t feel anything

at all. When it was time to get off the sitting platform

following zazen, I was supposed to be helping

Roshi put on his slippers, but because my

legs were sound asleep, I couldn’t move. Roshi

was quick to get over the numbness in his legs

and put on his own slippers so he would walk on

ahead. Somehow or other, I would get the feeling

back in my legs and feet and run after him.

Catching up with him, I would apologize saying,

“I’m sorry.” But while I thought I was bad, Roshi

was never angry with me.

One early morning during the summer at

4:30 a.m., the morning sun was beginning to

rise, the edge of the mountains was becoming

brighter, and I could hear the chirping of the

birds. Morning zazen was hard, but when it

ended, I had felt happy. “Today, I’ve done good

practice,” I thought. As Roshi and I were walking

along the hallway together, we came to some

stairs that were a little higher. There, as Roshi

climbed, I lifted his butt with both of my hands.

By lifting him up, I knew that he was breathing

a little easier.

It wasn’t only in the morning. On any day,

when Roshi came out of his room, he always

kept to one side of the hallway. And sometimes,

he would do curious things. Walking ahead of

me, he suddenly bent over and, breathing heavily,

he rearranged something on the floor.

What do you think he was doing?

At Eiheiji, each person wears slippers with

own name on them. When you enter a room,

you always neatly arrange your slippers against

the wall. If there are five people in a room, then

there should be five pairs of slippers neatly

arranged in the hallway outside the room. Occasionally,

there was a pair of sandals that were

not neatly arranged. Roshi would then suddenly

bend over and then straighten himself up.

Slowly standing up – he was already more than

80 years old – and smiling like a child, he would

say “Ah! Those sandals have attained Buddhahood.”

During the seven months I served as one

of his attendants, I had that experience several

times. Naturally, the other monks doing this job

also had the same experience. Back at the room

where his assistants on duty gathered, we wondered

to ourselves, “What do you think it

means? It surely means we should treat the slippers

with care.” This is what we imagined as we

spoke together about this.

It wasn’t only slippers that attained Buddhahood.

At Eiheiji, there is a twenty- tatami mat

room called “Shoken no Ma” where visitors are

met. At one end of the room, there is a

tokonoma with a big incense pot. Whenever a

group of visitors came to this room, a large stick

of incense about twelve inches long was lit and

placed in that pot. One day, the stick of incense

I had put in the pot was leaning to one side.

Coming into the room, Roshi immediately

noticed it and said,

“Now, now. A stick of incense should be

placed straight. Put it in once again.”

“Yes,”

I said and with great care and attention, I

reset the stick of incense making sure it was

straight. Once again, with a child-like smile he

said,

“Yes, that’s the way it should be. Now that

stick of incense has attained Buddhahood.”

The stick of incense became a buddha.

One time, Roshi was standing in the hallway

to one side and I came out of the assistants’

room in a hurry quickly closing the paper door

and it made a loud noise as I shut it. Roshi said,

“Hey! Paper doors should be closed slowly.

Do it again.”

“Yes,”

I said. I reopened and closed the door once

again, this time taking great care to do it slowly

and quietly. Wouldn’t you know, there was that

smile again,

“That’s right. That the way to close it. Now,

the door has attained Buddhahood.”

Slippers, incense, the door, there may have

been other things as well that attained Buddhahood.

Those three things are the ones I clearly

remember.

Later, after I had practiced for three years at

Eiheiji, I returned to my home temple in Niigata,

and became the resident priest of that temple. In

1993, Miyazaki Roshi was installed as the 78th

Head Abbot of Eiheiji.

He became the abbot of Eiheiji at the age of

93 and since he was a rare and great Zen maser

who continued his practice centered on zazen

until he died at the age of 108, he attracted the

attention from people in all directions. In 2004,

NHK(Japan Broadcasting Corporation)-TV did a

special program on him called “104 years old

Zenji of Eiheiji.” Since I served directly as his

attendant, my eyes were glued to the television

when this program aired.

At the age of eleven, he had left his parent’s

house and entered a temple. He had smoked

cigarettes when he was young but made great

effort to stop smoking. At the age of 60, he contracted

miliary tuberculosis. One side of his

lungs couldn’t move. This was how I learned the

reason for his heavy breathing when he was

walking. He may have breathed heavily during

zazen as well.

There was a surprising thing he said during

this TV special.

“I am Miyazaki Ekiho. I am Eiheiji.”

I thought, “Hmmm. ‘I am Eiheiji.’ The 78th

Head Abbot of Eiheiji said this…” Eiheiji had

been founded by Dogen Zenji in 1244. After

that, many monks who cherished Dogen Zenji

came from around Japan to train there. But

wasn’t it too much to say, “I am Eiheiji”, no

matter who you are?” This is what I thought to

myself.

After saying this, he continued by saying,

“Eiheiji and I are one. There is nothing as important

as oneself, but that important self lives

together with many monks in a building

designed as a monastery. We live together with

trees, mountains, rivers, and all sorts of animals.

We live together in a natural environment. Since

people as well as the environment are the self, to

take care of Eiheiji is to take of oneself.”

I felt a little bit of relief when even Miyazaki

Zenji said that the most important thing is oneself.

And then, when you look closely at that

important self, you understand how it is that we

are able to live by means of many people, things,

and the environment. He was saying that it isn’t

possible to not take of all the things around us.

When I heard those words, the meaning of

Zenji’s words when I was training at Eiheiji

about the slippers, incense, and the door attaining

Buddhahood made sense. Since he was one

with the monks, when a monk’s slippers were

not lined up, it was the same as having his own

slippers out of line. So, he had no choice but to

straighten them up. He had to treat the slippers

with care and that was the same as for the

incense and for the door. Truly, he had removed

the walls between himself and other by holding

onto that 1.5 personal pronoun relationship.

This was precisely by coexisting with other

people and in so doing he taught me there is

happiness in living that way. The bottomless

smile on Zenji’s face spoke of that happiness.

Finally, as a specific practice, I would like to

introduce a poem titled “Lining Up Footwear.”Lining Up Footwear

Aligning footwear, the mind is also aligned.

Aligning the mind, footwear is also aligned.

If you align your footwear when you remove them,

Your mind will not be disordered when you put them back on.

If someone leaves their footwear out of order,

Align them without saying anything.

If you do it like this,

Then surely the minds of the world’s people will be aligned.What do you think?

When you enter a Japanese toilet, you of

course line up your slippers neatly. But if someone

else’s slippers are disordered, it is important

to also straighten them up. But when you do

this, don’t take the easy way and line them up

with your feet. Stretch out your arms and use

your hands. Treat the slippers with care. It is

important to think about the next person who

will use those slippers and straighten them out.

In each moment of our everyday lives to realize

that we live together with those people,

things, and environment that surrounds us is

what connects us with each other’s happiness.

![]()

Un maitre du soto zen - 1902-2008 - 95 ans de zazen

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aC2ncga_4Hg