ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

骆芃芃 Luo Pengpeng (1958-)

Tartalom |

Contents |

Luo Pengpeng Keletről... A Kínai Nemzeti Művészeti Akadémia festmény- és kalligráfiakiállítása

|

Luo Pengpeng From the East... Chinese National Academy of Arts - painting and calligraphy exhibition, Budapest, 2017

|

Chinese Seals

Almost every Chinese painting bears one or more

bright red (cinnabar) seal (yinzhang), and such

impressions are often seen next to the inscription

on Chinese calligraphy works. The artist is the first

to sign his work with his seal which thus serves a

function similar to that of a Western artist’s signature.

An artist might own more than one personal seal. The

absence of a seal from a painting or a calligraphy work

indicates that the work was deemed to be below par.

Other individuals who came into contact with the

work in some way—owners, collectors, communities,

institutitons—would also add their seals to the piece

as a signal of acknowledgement. There are a number

of classic works with entire collections of seals on

them. The use of large, exceedingly wide borders was

a privilege of the imperial court. Small collectors’ seals

left very thin lines on the piece so as not to interfere

with the original composition.

Seal carving is a minor art form, one of the ancillaries

to calligraphy. The characters on seals use the archaic

styles large seal script (da zhuan) and/or small seal

script (xiao zhuan). Developed in ancient times, these

styles have changed a lot over the centuries. The

script used on a piece suggests the historical period

when it was made. The requirement to abide by the

specific rules of the art and create a composition in a

very confined space make seal design a real challenge

to artists. The inscription containing the full name or

one or two characters of the name (art name, age,

place of origin, studio name, title), some other text or

literary quotation of varying length, is enclosed within

a border consistent in style. The last character of the

text often refers to script (shu), treasure (bao), or the

seal (yin) itself.

Characters are not allowed to stick out; chief

components may not be missing; rotation of

characters is unacceptable. In view of the open and

closed outlines the use of space is always individually

designed. The proportions may be changed, but

distortion in the extreme is permitted only within the

limits of recognisability. The stress is on imaginative

playfulness, witty lines, a unique composition, and an

interestingly weird use of space. Seals may also have

pictorial elements (flowers, boats, gourds, musical

instruments), human figures (Buddhas), or animals

(fish, bird) carved into the stone.

Seal imprints are always bright vermillion but vary

in size and shape: they may be square, rectangular,

rounded, circular, oval, or even amorphous. The

number of characters inscribed depends on the text

and the size of the working surface of the seal. The

characters are read top-down and right-to-left in

the traditional manner, although a seal imprint may

sometimes be read in a contrary or zigzag direction.

With four characters, various reading directions

give rise to different interpretations, an opportunity

sometimes intentionally exploited by seal carvers.

Borderlines around the edges are optional. The seal may

imprint the background in red, leaving white characters

(zhu wen) or, conversely, imprint the characters in red

(bai wen) and leave the background white. The former

kind is also referred to as yin seals, while the latter are

called yang seals. The imprint of a white seal is darker in

tone; that of a red one is lighter. In accordance with the

standards of seal script, the lines of a design are usually

of equal width, although irregularities in carving may

of course produce a less uniform effect. Along with

chips and cracks, these features contribute to the

uniqueness of a seal and help establish its authenticity.

The placement of a seal imprint, fitting it into the

composition of a painting, is a task requiring just as

much care and consideration as the creation of the

picture itself or adding inscriptions (colophons). On

calligraphy works done entirely in black ink, seal marks

in bright vermillion provide stark contrast regardless of

size or proportions.

The vermillion paste (yinni) is composed of eight

ingredients: cinnabar, pearl, musk, coral, ruby, moxa,

castor bean and red pigment. Seal paste is stored in

small chinaware containers or metal boxes.

The seal stone is usually a kind of greenish or

yellowish-brown serpentinite [soapstone?] with

irregular specks, patches, and veins. In earlier times,

seals were also made of ivory, precious stones, jade, and

even hardwood and bronze. Soft serpentinite is easily

carved. At first, a prismatic or cylindrical body is cut out

of the stone and polished on the sides. The seal knob

was often decorated with pictorial elements carved so

as to emphasize any mysterious refraction or veins in

the stone. Motifs included geometric shapes, figures of

animals (tortoise, dragon, snake, fish), stylized figures

of felines and humans, and ornaments.

The side of the seal stone may bear an inscription

(kuan wen) engraved with a cut edge chisel using a

‘chipping’ technique (dao jiao ke fa). One edge of the

resulting stroke is straight, the other is jagged. Ink

rubbings of such inscriptions (ta kuan) create white

characters on a black background. The rubbings are

always exhibited alongside the vermillion red seal

impressions.by Janisz Horváth

A visitor views seal engraving works displayed during an exhibition held at the China International Exhibition Center in Beijing, capital of China, Aug. 21, 2019. About 120 seal engraving and calligraphy works made by Luo Pengpeng, a master of the art, and her students were on display during the five-day exhibition. Chinese seal engraving was included in UNESCO's intangible cultural heritage list in 2009.

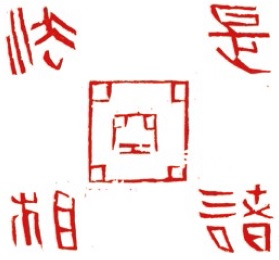

Luo Pengpeng: pecsétnyomó vésete és lenyomataSeal by Luo Pengpeng

般若波罗密多心经句“是诸空法“

Prajñāpāramitāhŗdaya szív szútraPrajñāpāramitāhŗdaya Heart Sutra

2011丹东石 Dandong-i kő

白朱文 (bai zhu wen) fehér–cinóber pecsétDandong stone (bai wen) white seal

10×10×12 cm„Üresség a sajátja mindennek”

A Négy Égtáj és a Közép jelképe

a többszörös négyzetformákkal.‘Emptiness is a property of all things’

The symbol of the four cardinal points

and the Middle with the multiple squares.

Kínai pecsétnyomók

A kínai festményeken majdnem mindenhol, a kalligráfiákon

legtöbbször a felirat alatt/mellett látható

egy vagy több vöröses színfolt, a cinóber színű pecsét

(yinzhang). Először az alkotó minősíti pecsételéssel

a munkáját, a nyugati képzőművész aláírásához

hasonlóan. Saját pecsétből lehet több is. Ha egy

képen, íráson nincs egy darab pecsét sem, akkor az

nem ütötte meg a kívánt színvonalat. Sokszor kerülnek

még a képre a művel valamilyen módon kapcsolatba

került más személyek – tulajdonosok, gyűjtők,

közösségek, intézmények – a hitelesség érdekében

elhelyezett jelei is. Némelyik klasszikus alkotáson

a pecsétek egész gyűjteménye halmozódott fel.

A nagy formátumú, nagyon vastag keret használata

csak a császári udvar kiváltsága volt. A műgyűjtők kis

pecsétje pedig egészen vékony vonalú, hogy ne zavarja

az eredeti kompozíciót.

A pecsét, a pecsétfaragás a kalligráfiának egyik kistestvére,

írásjegyei az ókorban kialakult archaikus nagy

és/vagy kis pecsétírás (da zhuan, xiao zhuan) stílusában

készültek/készülnek. Ezek formája az évszázadok alatt

rengeteget változott, így az egyes felhasznált írásképek

időszakokra, történelmi korokra is utalnak. A külön

esztétikai nyelvezetet használó vonalvezetés és

az adott kicsi, szűk felületre való komponálás nehéz

művészi feladat. A teljes nevet vagy annak egy-két

írásjegyét (művésznevet, életkort, származási helyet,

műterem-elnevezést, titulust) vagy egyéb szöveget,

rövidebb-hosszabb irodalmi idézetet tartalmazó felirat

egy stílusosan egységes, lezárt keretbe kerül. A szöveg

utolsó írásjegye sokszor az írásra (shu), az értékre (bao)

vagy magára a pecsétre (yin) vonatkozik.

Az írásjegy nem lóghat ki, részeiből nem hiányozhat

fontos alkotóelem, nem forgatható. A nyitott és zárt

körvonalak miatt a térkihasználás mindig egyedileg

tervezett. Az arányok megváltoztathatók, de a szélsőséges

torzítás csak a felismerhetőség határain belül

megengedett. A lényeg az ötletesen játékos, szellemes

vonalvezetés, egyedi kompozíció, érdekes helykihasználás.

Olykor ábra (virág, hajó, lopótök, hangszer), figura

(Buddha) vagy állatkép (hal, madár) is lehet a pecséttéma.

A különböző formájú és méretű, mindig élénk cinóber

színű pecsétlenyomat lehet négyzetes, téglalap, lekerekített,

kör, ovális, vagy akár amorf alakú is. A vésett

írásjegyek száma a szövegtől és a felület nagyságától is

függ. Az írásjegyek összeolvasása is a jobb felső sarokból

induló hagyományt követi, de ellentétes vagy cikkcakk

irányú olvasat is ismeretes. Négy írásjegy esetén a

más irányú összeolvasás sokszor értelmezési kérdést is

felvet. Ezzel néha tudatosan is játszanak a faragók.

A kerettel vagy anélkül készített pecsét lehet fehér

(bai wen) – ez esetben a szöveg vonalai „üresek” és a

környezet festékes –, vagy ennek kifordítottja a cinóbervörös

(zhu wen) feliratú. Az előbbit yin, az utóbbit

yang pecsétnek is hívják. A fehér pecsét tónusértékében

erősebb, a cinóber pecsét világosabb. A vonalak

vastagsága egy rajzolaton belül – a pecsétírás stílusnak

megfelelően – általában egyforma, bár a faragási egyenetlenségek

természetesen más látványt eredményezhetnek.

Ezek, illetve a törési hibák hitelesítő, egyedítő

sajátosságok a pecséteken.

A pecsétlenyomat elhelyezése, a kompozícióba való

beillesztése ugyanolyan megfontolást igénylő művészi

feladat, mint a képalkotás és a kísérő felirat. A csak

fekete tust használó kalligráfiákon az élénk cinóber

pecsét egyértelmű színes kontraszt a kép méretétől,

aránykülönbségétől függetlenül.

A cinóberpaszta (yinni) nyolc összetevőből álló

massza: cinnabarit érc, gyöngy, pézsma, korall, rubin,

moxa, ricinus és vörös pigment. Porcelánedénykében

vagy fémdobozban tárolják.

A pecsétkő anyaga többnyire szabálytalan lefutású

ereket, foltokat tartalmazó szerpentinit valamelyik zöldes

vagy sárgás-barnás árnyalatú fajtája. Régen készült

pecsét elefántcsontból, nemes drágakőből, jádeitből

vagy keményfából, bronzból is. A könnyen faragható

szerpentinitet először hasáb vagy henger formájúra

vágják, oldalait simára lecsiszolják. A felső fogó felületet

sokszor figurálisan megfaragják, figyelve arra,

hogy a kő sejtelmes fénytöréseit, esetleges erezetét a

körplasztika kiemelje. A faragott formák között lehetnek

mértani testek, állatfigurák (teknősbéka, sárkány,

kígyó, hal) stilizált macskafélék vagy emberi alakok, ornamentikák.

A pecsétkő oldalára alkotói szöveget (kuan wen)

véshetnek, amelyet a vágott élű vésővel „kipattintós”

(dao jiao ke fa) technikával vésnek. Ennek eredménye

az egyik szélén egyenes, a másikon recés vonal. Az erről

készült tuslenyomatok a bedörzsöléses pacskolatok

(ta kuan) módjára készülnek, ezért lesznek itt fekete

alapon fehérek az írásjegyek. Bemutatásuk mindig a

cinóber színű pecsétnyomattal együtt történik.Horváth Janisz